Abstract

Background

Severe alpha1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency associated with low AAT blood concentrations is an established genetic COPD risk factor. Less is known about the respiratory health impact of variation in AAT serum concentrations in the general population. We cross-sectionally investigated correlates of circulating AAT concentrations and its association with FEV1.

Methods

In 5187 adults (2669 females) with high-sensitive c-reactive protein (CRP) levels ≤ 10 mg/l from the population-based Swiss SAPALDIA cohort, blood was collected at the time of follow-up examination for measuring serum AAT and CRP.

Results

Female gender, hormone intake, systolic blood pressure, age in men and in postmenopausal women, as well as active and passive smoking were positively, whereas alcohol intake and BMI inversely correlated with serum AAT levels, independent of CRP adjustment. We observed an inverse association of AAT with FEV1 in the total study population (p < 0.001), that disappeared after adjustment for CRP (p = 0.28). In addition, the AAT and FEV1 association was modified by gender, menopausal status in women, and smoking.

Conclusion

The results of this population-based study reflect a complex interrelationship between tobacco exposure, gender related factors, circulating AAT, systemic inflammatory status and lung function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alpha1-antitrypsin (AAT), a polymorphic inflammation-sensitive plasma protein with antiprotease activity, protects the lung tissue from destruction by neutrophil elastase. Severe and intermediate AAT deficiency is one of the most common inherited diseases on a global scale [1]. It increases the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) in active smokers [2, 3]. The two most common deficiency alleles are the S- and Z-allele, but at least 30 rare, additional alleles exist that are associated with reduced or absent plasma AAT levels [4].

International AAT deficiency registries have advanced the epidemiologic understanding of genetically determined AAT deficiency. Much less is known about the respiratory health impact of variation in AAT serum concentrations as observed in the general population. According to a study in healthy blood donors only 26% of the variance in circulating AAT was explained by known AAT gene variants [5]. In a population-based sample of school children pulmonary function was positively associated with C-reactive protein (CRP)-adjusted AAT levels, independent of PI phenotypes [6]. In contrast, an inverse association between inflammation-sensitive proteins, including non-CRP adjusted serum AAT, and pulmonary function has been described in population-based samples of adults [7, 8]. These reported opposite directions of the lung function/AAT association may in part be due to differences in adjustment for CRP between the studies. They also agree with the dual role of AAT as both, an antiprotease and an inflammatory marker. Low-grade systemic inflammation is increasingly being recognized as a COPD risk factor [9].

In the population-based Swiss Cohort Study of Air Pollution and Lung Disease in Adults (SAPALDIA) we investigated the potential value of circulating AAT as a biomarker for susceptibility to respiratory disease in the general population. First, we identified environmental and lifestyle factors associated with AAT concentrations in the blood. Second, we investigated the cross-sectional association between circulating AAT concentrations and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1).

Methods

Study population

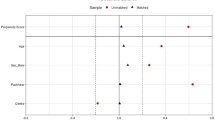

The SAPALDIA cohort has been described [10, 11]. At baseline in 1991 the SAPALDIA participants were aged 18–60 years. They are predominantly of European-Caucasian ethnicity and Swiss nationality. They were randomly selected from eight population registries representing the three major Swiss language regions and including both, urban and rural areas. Health examinations at baseline and after 11-years included an interview about respiratory health, occupational and lifestyle exposures as well as spirometry. Participation rate at baseline was 59.3%. The current, cross-sectional investigation of AAT is restricted to follow-up data collected in 2002/2003 when the blood bank was established (Figure 1 and Table 1 for more detail). Ethical approval for the study was given by the central ethics committee of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences and the Cantonal Ethics Committees for each of the eight examination areas.

Participation in SAPALDIA baseline and follow-up examination and in the current cross-sectional study. The current, cross-sectional investigation of AAT is restricted to data collected in 2002/2003 when the blood bank was established. The analysis of factors correlated with serum AAT levels (Tables 2 and 7) is restricted to 5187 follow-up participants (*), whereas the association between serum AAT and FEV1 was further restricted to 4449 follow-up participants with valid lung function measurements (**) (Tables 4, 5 and 6).

Measurements

Lung function

Lung function was assessed using spirometry (Sensormedics model 2200, Yorba Linda, USA) according to ATS criteria The present analysis focused on FEV1 expressed as % predicted, derived from SAPALDIA-specific prediction equation [12].

Tobacco exposure, alcohol intake and female hormone-related variables

Information about active and passive smoking was collected by an extended version of the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) questionnaire [13]. Smoking was categorized as current (smoking within month before interview), former, and never smoking at follow-up. Never and former smokers were classified as environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposed based on an affirmative answer to a question about regular exposure to ETS in the 12 months before the interview. Smoking intensity was calculated as total pack years smoked ([years of smoking * mean cigarettes/day]/20). Current smokers were a priori divided into two subgroups: <15 cigarettes/day vs. ≥ 15 cigarettes/day. Alcohol consumption was a priori classified as daily versus not daily drinking (≥1 vs. <1 alcoholic drink per day).

Women were categorized as pre- and postmenopausal. Women whose menses had become less regular within 12 month before the interview were defined as perimenopausal. Current exogenous hormonal intake was assessed by the questions "have you ever taken oral contraceptives (OC) or hormone replacement therapy (HRT)?", and "were you still taking OC or HRT during the last month before the interview?"

Physical examination

Mean values of 2 automatic measurements of systemic blood pressure (BP) (OMRON 705 CP, Tokyo, Japan) were used and pulse pressure (PP) – a measure of artery stiffness – was calculated as the difference between systolic and diastolic BP [14]. Weight and height were measured by electronic (TERRAILLON, Bradford, MA, USA), and telescopic scales (SECA, Hamburg, Germany), respectively for the assessment of body mass index (kg/m2; BMI).

Serum analysis

AAT (g/l) and high-sensitivity c-reactive protein (CRP) (mg/l) concentrations were determined by latex-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assays (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany on a Roche COBAS INTEGRA analyzer, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) with interassay coefficients of variation below 5%. Lower detection rates for the AAT and CRP assays were 0.21 g/l, and 0.1 mg/l, respectively.

Statistical analysis and sample size

All statistical analyses were restricted to subjects without signs of an acute infection (CRP ≤ 10 mg/l).

First, we identified the independent association of gender, age, BMI, smoking status, packyears, ETS exposure, and alcohol consumption with AAT concentrations among 5187 participants. Analysis of covariance with and without CRP adjustment was performed to estimate adjusted mean (SE) AAT serum concentrations (g/l).

Second, we investigated the association between circulating AAT and FEV1% predicted. Given the correlations of CRP with both, AAT (Table 2) and FEV1 (Table 3), we investigated the association with and without CPR-adjustment. The regression models included sex, study area, systolic blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), smoking status (never, former, current), alcohol consumption, ETS (never and former smokers), pack years smoked (current smokers), time since quitting (former smokers), cigarettes smoked/day (current smokers), menopausal status and hormone intake (women) as covariates. Analysis of covariance was performed to estimate adjusted mean FEV1% predicted values (standard errors) for AAT quintile classes. To evaluate dose-response relationships, predictor variables were categorized into suitable quantile classes, and regression models without the respective predictor variables were computed. A Cuzick's trend test [15] was then used to test whether regression residuals showed a monotonous association with increasing levels of the predictor in question. Effect modification was assessed by including interaction terms between AAT as a continuous variable and the potential effect modifier of interest in the models. Interactions with a p-value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant [16]. In the absence of information on SERPINA1 genotype variants and to avoid unrecognized confounding or effect modification by unrecognized severe and intermediate AAT deficiency genotypes, the main multiple linear regressions were restricted to participants exhibiting normal serum AAT concentrations (≥ 0.9 g/l; indicating the normal cut-off value for AAT serum concentrations according to the consensus reference data [CRM470/RPPHS] [17]). The main FEV1 analyses therefore included 4297 subjects (never smokers = 2028, former smokers = 1336, current smokers = 933) with complete data on lung function and covariates. Nevertheless and despite limited sample size, predicted means for the small category of subjects with serum AAT < 0.90 g/l (Q0: n = 152) are also presented in Tables 4, 5 and 6. STATA software, release 8.2 (StataCorp, TX, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

At baseline 9651 subjects were recruited into the SAPALDIA cohort, of whom 8881 underwent lung function testing (Figure 1). Of the 7673 participants in the interview at follow-up (Fig.1, see *), 5187 were included in the analysis of factors associated with serum AAT (Table 2 and 7). Equivalently, of the 6218 participants in both, interview and spirometry at follow-up (Fig. 1, see **), 4449 were included in the analysis of the serum AAT/FEV1% predicted association (Tables 4, 5 and 6). A comparison of baseline characteristics between all SAPALDIA participants (n = 9651) and subjects included in the two current sub-studies (AAT determinants (n = 5187); AAT/FEV1% predicted (n = 4449) is listed in Table 1. As previously described in detail, never smokers were overrepresented among participants at follow-up and thus in the two cross-sectional sub-studies [11].

AAT serum levels: association with age, gender, anthropometrics, blood pressure, lifestyle, and hormonal variables

At the follow-up examination, mean (SD) age in men (n = 2518) and women (n = 2669) included in the investigation of AAT determinants was 51 [12] and 52 [11] years, respectively, and mean BMI 26.45 (3.72) and 24.96 (4.55) kg/m2, respectively. In both gender groups combined, 23% reported current and 29% reported former smoking at follow up. Mean (SD) pack years smoked in current and former smokers was 30 [23] and 21 [23] pack years, respectively. Two thousand five hundred and nine subjects had never smoked actively (59% females), of whom 15% were exposed to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) within 12 months before the follow-up interview. Among these, 137 (35%) were exposed to ETS more than 3 hours per day. Among the premenopausal women, 166 (21%) reported oral intake of contraceptives, and hormone replacement therapy was reported by 524 (61%) of the postmenopausal women. Serum AAT concentrations ranged from 0.38 to 2.24 g/l with a mean (SD) of 1.26 (0.20) g/l. One hundred and seventy eight subjects (3.4%) had a serum AAT level below 0.9 g/l, the recommended test limit for further clinical and laboratory investigation of genetic AAT deficiency [17].

The associations of age, gender, anthropometric parameters, blood pressure, lifestyle and hormonal variables with serum AAT are shown in Tables 2 and 7. Women had higher circulating AAT concentrations (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

The AAT/age association differed by gender and menopausal status in women (p interaction <0.001 for both). In men and postmenopausal women age was positively associated with AAT whereas an inverse association was present in premenopausal women. None of the remaining AAT predictors was modified by gender. Systolic blood pressure and pulse pressure (data not shown) were positively associated with serum AAT (p trend = 0.002 and <0.001, respectively), BMI and regular alcohol consumption inversely. Serum AAT increased with tobacco smoke exposure in a dose-dependent fashion. ETS-exposed never smokers had higher AAT serum levels than non-exposed never smokers. Serum AAT was highest in active smokers consuming at least 15 cigarettes per day (p linear trend < 0.001).

In women, we assessed the association of menopausal status and intake of female hormones (oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy) with serum AAT (Table 7).

Among women without intake of female hormones, serum AAT was higher in premenopausal women (p = 0.003). Use of oral contraceptives (premenopausal) and of hormone replacement therapy (postmenopausal) was associated with elevated AAT concentrations in the blood (p < 0.001 for both).

The associations of serum AAT with the factors listed in Tables 2 and 7 were insensitive to CRP adjustment. CRP itself was positively associated with AAT (Table 2). Results in Tables 2 and 7 were insensitive to the exclusion of subjects with AAT levels below 0.9 g/l or below 1.04 g/l (0.9 g/l: normal cut-off for serum AAT [17]; 1.04 g/l: lower 10th percentile of the AAT distribution in this study).

AAT serum levels: association with lung function

In the total study population, AAT was inversely associated with FEV1, but only in the absence of CRP adjustment (Table 4).

The inverse association was restricted to men (not CRP adjusted p interaction AAT*gender = 0.007). The AAT/FEV1 association was also modified by smoking. An inverse association before CRP adjustment was observed in never/former smokers (p < 0.001) and in current smokers consuming 15 cigarettes or less per day. In contrast, CRP adjusted AAT and FEV1 were positively correlated in heavy current smokers (p = 0.01) (not CRP adjusted p interaction AAT*(current smokers >= 15 cigs/day vs. all others): = 0.14 in all subjects; = 0.03 in men; = 0.11 in women).

Results on the AAT/FEV1 association stratified by both, gender and smoking, are presented in Tables 5 and 6. As we observed a statistically significant interaction between menopausal status and AAT in all women, irrespective of smoking status and CRP adjustment (not CRP adjusted p interaction AAT*menopausalstatus = 0.008), analyses in women were further stratified by menopausal status.

Among participants not currently smoking, FEV1 was inversely related to AAT in both, men and postmenopausal women, irrespective of CRP adjustment (Table 5).

In contrast, premenopausal non-smoking women exhibited a positive correlation between FEV1 and CRP-adjusted serum AAT (p = 0.02).

No inverse associations between FEV1 and AAT were observed in current smokers upon stratification by gender (Table 6).

Upon stratification by smoking intensity (< vs. ≥ 15 cigs/day) the association between AAT and lung function became positive in the group of heavy smokers after adjustment for CRP in both, men and postmenopausal women (men: p = 0.04; women: p = 0.05). Unfortunately, we had insufficient power to stratify analysis in premenopausal women by smoking intensity.

Analyses of the AAT/FEV1 associations were also repeated by increasing the exclusion cutoff to AAT levels below 1.04 g/l (lower 10th percentile of the AAT distribution in this study). The results presented in Tables 4, 5 and 6 were insensitive to this additional exclusion. It is notable that subjects with AAT < 0.9 g/l generally exhibited good lung function (Tables 4, 5 and 6), although data in this category was sparse.

Discussion

The main and general message of the present paper is that circulating AAT was inversely correlated with FEV1 in this general adult population, but only in the absence of CRP adjustment. The strengths of this study include its population-based design, and the detailed characterization of the participants which allowed us to investigate both, factors associated with circulating AAT as well as the association of the latter with lung function. Based on CRP measurements we were able to exclude subjects with laboratory evidence of inflammation at the time of the blood draw, and to control for low-grade systemic inflammation as potential confounder. These study advantages allowed us to demonstrate the complexity of the interrelationship between tobacco exposure, gender, circulating AAT and CRP as well as lung function.

Positive associations between active smoking and AAT levels have been reported before [18, 19]. We additionally considered ETS and smoking intensity and demonstrated a positive dose-response relationship between tobacco exposure and serum AAT, that was not confounded by CRP. But this positive association between tobacco exposure and circulating AAT did not consistently translate into an inverse association between AAT and lung function in smokers. In fact we found a positive AAT/FEV1 association in men and postmenopausal women who smoked heavily, in line with the interaction of smoking and inherited AAT deficiency on COPD risk and lung function [20]. Von Ehrenstein et al [6] found adverse effects of ETS on lung function to be strongest in children with low, CRP-adjusted AAT levels. The differences in FEV1 that we observed were small from an individual perspective; yet even small differences in FEV1 at normal levels are predictive of overall or cause-specific mortality and may ultimately shift a substantial percentage of the general population into the group of subjects with clinically relevant lung function deficits [21].

Our results suggest that female hormones influence circulating AAT levels and modify the AAT/lung function association. Gender differences in both, circulating AAT [20] and respiratory health [22] are well established and may reflect biological differences in the interrelations between smoking, AAT and lung function. Gender differences in AAT levels were even present in the situation of severe AAT deficiency although the results were not adjusted for hormone intake [23]. While previous reports on the association between use of oral contraceptives and AAT in the blood exist [24, 25], our study extends this association to postmenopausal hormone intake. Our findings are compatible with an effect of estrogens or progesterone on hepatic AAT metabolism, which may be mediated by an inhibition of cytochrome P-450 activities [26].

The observed modification of the FEV1/AAT association by smoking and hormonal factors as well as by CRP-adjustment may reflect the dual role of AAT as a respiratory disease biomarker. The net impact of AAT on lung function seems to be the result of context-dependent (i.e. smoking, gender) and contrasting protective and inflammatory effects in the respiratory tract. On the one hand, elevated serum AAT can reflect a beneficial shift of the protease-antiprotease balance, the centre piece of the pathophysiological pathway mediating the effect of severe AAT deficiency on COPD. On the other hand elevated serum AAT can also reflect low-grade inflammatory processes in the lung [27], a hypothesized COPD risk factor [9]. Consistent with these findings, we could detect a positive relationship between AAT and CRP concentrations. Previous studies observed inverse association between inflammation-sensitive proteins, including serum AAT, and pulmonary function in population-based samples of adults [7, 8]. Subjects with CRP > 10 mg/l were not excluded, and smoking was not investigated as a potential effect modifier. Significantly higher AAT levels were even reported for AAT deficient (PIZZ) patients with COPD compared to PIZZ individuals without COPD thus further supporting the hypothesis that AAT levels may also represent an ongoing inflammatory process [28].

The observed inverse association observed between AAT and BMI might also be reflecting different roles of AAT. In general, positive association between CRP and BMI have been observed among obese persons, an effect that was attributed to low-grade systemic inflammation [29]. However, the acute phase response is a complex signalling pathway and different acute phase proteins are distinctly regulated and expressed [30]. Engström et al [31] found a number of inflammation-sensitive proteins to be positively related to BMI, yet AAT levels were highest in healthy men in the lowest BMI quartile.

The cross-sectional nature of the study prohibits assessment of cause and effect as well as differentiation between etiological and prognostic effects of variation in AAT concentrations. This aspect may be of relevance to considerations about the pathophysiological mechanism underlying the observed associations. Dahl et al[20] found the AAT MZ genotype to be associated with lung function among individuals with clinically established COPD, but not among subjects without COPD in the general population. A possible criticism to our paper is the lack of information about potential AAT deficiency pheno- or genotypes in the study population. But we specifically investigated the potential value of variation at the serum AAT protein levels as a biomarker for lung function impairment in the general population. Since the observed associations were insensitive to the AAT cut-off level rare, unrecognized AAT deficiency alleles are an unlikely source of bias in this study. Another concern of the current cross-sectional study, which is embedded into the SAPALDIA cohort, is the potential for selection bias due to non-participation. Never smokers were more likely to participate at follow-up [11]. If serum AAT was associated with the likelihood of participation at baseline or follow-up this could have distorted results on associations between AAT and other factors. Although unlikely, we cannot definitively rule out such bias in the absence of AAT measurements in non-participants.

Conclusion

Our cross-sectional results demonstrated that a complex interrelationship among tobacco exposure, gender, circulating AAT, lung function, and systemic inflammatory status exists. If the observed interactions between these variables are confirmed in larger and longitudinal studies, the potential utility of circulating AAT as a biomarker for susceptibility to respiratory disease seems limited. The reported interactions are also relevant to studying the impact of genetic variation in AAT on lung health.

SAPALDIA Team

Study directorate

T Rochat (p), U Ackermann-Liebrich (e), JM Gaspoz (c), P Leuenberger (p), LJS Liu (exp), NM Probst Hensch (e/g), C Schindler (s).

Scientific team

JC Barthélémy (c), W Berger (g), R Bettschart (p), A Bircher (a), G Bolognini (p), O Brändli (p), M Brutsche (p), L Burdet (p), M Frey (p), MW Gerbase (p), D Gold (e/c/p), W Karrer (p), R Keller (p), B Knöpfli (p), N Künzli (e/exp), U Neu (exp), L Nicod (p), M Pons (p), E Russi (p), P Schmid-Grendelmeyer (a), J Schwartz (e), P Straehl (exp), JM Tschopp (p), A von Eckardstein (cc), JP Zellweger (p), E Zemp Stutz (e).

Scientific team at coordinating centers

PO Bridevaux (p), I Curjuric (e), SH Downs (e/s), D Felber Dietrich (c), A Gemperli (s), D Keidel (s), M Imboden (g), P Staedele-Kessler (s), GA Thun (g)

(a) allergology, (c) cardiology, (cc) clinical chemistry, (e) epidemiology, (exp) exposure, (g) genetic and molecular biology, (m) meteorology, (p) pneumology, (s) statistics

References

de Serres FJ: Worldwide racial and ethnic distribution of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency: summary of an analysis of published genetic epidemiologic surveys. Chest 2002, 122:1818–1829.

Piitulainen E, Eriksson S: Decline in FEV1 related to smoking status in individuals with severe alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency (PiZZ). Eur Respir J 1999, 13:247–251.

Eriksson S, Lindell SE, Wiberg R: Effects of smoking and intermediate alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency (PiMZ) on lung function. Eur J Respir Dis 1985, 67:279–285.

Ferrarotti I, Baccheschi J, Zorzetto M, Tinelli C, Corda L, Balbi B, Campo I, Pozzi E, Faa G, Coni P, Massi G, Stella G, Luisetti M: Prevalence and phenotype of subjects carrying rare variants in the Italian registry for alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. J Med Genet 2005, 42:282–287.

Oakeshott JG, Muir A, Clark P, Martin NG, Wilson SR, Whitfield JB: Effects of the protease inhibitor (Pi) polymorphism on alpha-1-antitrypsin concentration and elastase inhibitory capacity in human serum. Ann Hum Biol 1985, 12:149–160.

von Ehrenstein OS, von Mutius E, Maier E, Hirsch T, Carr D, Schaal W, Roscher AA, Olgemoller B, Nicolai T, Weiland SK: Lung function of school children with low levels of alpha1-antitrypsin and tobacco smoke exposure. Eur Respir J 2002, 19:1099–1106.

Welle I, Bakke PS, Eide GE, Fagerhol MK, Omenaas E, Gulsvik A: Increased circulating levels of alpha1-antitrypsin and calprotectin are associated with reduced gas diffusion in the lungs. Eur Respir J 2001, 17:1105–1111.

Engstrom G, Lind P, Hedblad B, Wollmer P, Stavenow L, Janzon L, Lindgarde F: Lung function and cardiovascular risk: relationship with inflammation-sensitive plasma proteins. Circulation 2002, 106:2555–2560.

Gan WQ, Man SF, Senthilselvan A, Sin DD: Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Thorax 2004, 59:574–580.

Martin BW, Ackermann-Liebrich U, Leuenberger P, Kunzli N, Stutz EZ, Keller R, Zellweger JP, Wuthrich B, Monn C, Blaser K, Bolognini G, Bongard JP, Brandli O, Braun P, Defila C, Domenighetti G, Grize L, Karrer W, Keller-Wossidlo H, Medici TC, Peeters A, Perruchoud AP, Schindler C, Schoeni MH, Villiger B, .: SAPALDIA: methods and participation in the cross-sectional part of the Swiss Study on Air Pollution and Lung Diseases in Adults. Soz Praventivmed 1997, 42:67–84.

Ackermann-Liebrich U, Kuna-Dibbert B, Probst-Hensch NM, Schindler C, Dietrich DF, Stutz EZ, Bayer-Oglesby L, Baum F, Brandli O, Brutsche M, Downs SH, Keidel D, Gerbase MW, Imboden M, Keller R, Knöpfli B, Kunzli N, Nicod L, Pons M, Staedele P, Tschopp JM, Zellweger JP, Leuenberger P: Follow-up of the Swiss Cohort Study on Air Pollution and Lung Diseases in Adults (SAPALDIA 2) 1991–2003: methods and characterization of participants. Sozial- und Präventivmedizin/Social and Preventive Medicine 2005, 50:1–19.

Brandli O, Schindler C, Kunzli N, Keller R, Perruchoud AP: Lung function in healthy never smoking adults: reference values and lower limits of normal of a Swiss population. Thorax 1996, 51:277–283.

Burney PG, Luczynska C, Chinn S, Jarvis D: The European Community Respiratory Health Survey. Eur Respir J 1994, 7:954–960.

Dart AM, Kingwell BA: Pulse pressure--a review of mechanisms and clinical relevance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001, 37:975–984.

Cuzick J: A Wilcoxon-type test for trend. Stat Med 1985, 4:87–90.

Fleiss JL: Analysis of data from multiclinic trials. Control Clin Trials 1986, 7:267–275.

Dati F, Johnson AM, Whicher JT: The existing interim consensus reference ranges and the future approach. Clin Chem Lab Med 2001, 39:1134–1136.

Lellouch J, Claude JR, Thevenin M: Smoking and serum alpha 1-antitrypsin in 1296 healthy men. Clin Chim Acta 1979, 95:337–345.

Ashley MJ, Corey P, Chan-Yeung M: Smoking, dust exposure, and serum alpha 1-antitrypsin. Am Rev Respir Dis 1980, 121:783–788.

Dahl M, Nordestgaard BG, Lange P, Vestbo J, Tybjaerg-Hansen A: Molecular diagnosis of intermediate and severe alpha(1)-antitrypsin deficiency: MZ individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may have lower lung function than MM individuals. Clinical Chemistry 2001, 47:56–62.

Kunzli N, Ackermann-Liebrich U, Brandli O, Tschopp JM, Schindler C, Leuenberger P: Clinically "small" effects of air pollution on FVC have a large public health impact. Swiss Study on Air Pollution and Lung Disease in Adults (SAPALDIA) - team. Eur Respir J 2000, 15:131–136.

Becklake MR, Kauffmann F: Gender differences in airway behaviour over the human life span. Thorax 1999, 54:1119–1138.

Piitulainen E, Tornling G, Eriksson S: Effect of age and occupational exposure to airway irritants on lung function in non-smoking individuals with alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency (PiZZ). Thorax 1997, 52:244–248.

Behr W, Schlimok G, Firchau V, Paul HA: Determination of reference intervals for 10 serum proteins measured by rate nephelometry, taking into consideration different sample groups and different distribution functions. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem 1985, 23:157–166.

Laurell CB, Kullander S, Thorell J: Effect of administration of a combined estrogen-progestin contraceptive on the level of individual plasma proteins. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1968, 21:337–343.

Laine K, Yasar U, Widen J, Tybring G: A screening study on the liability of eight different female sex steroids to inhibit CYP2C9, 2C19 and 3A4 activities in human liver microsomes. Pharmacol Toxicol 2003, 93:77–81.

Meyer KC, Rosenthal NS, Soergel P, Peterson K: Neutrophils and low-grade inflammation in the seemingly normal aging human lung. Mech Ageing Dev 1998, 104:169–181.

Silverman EK, Province MA, Rao DC, Pierce JA, Campbell EJ: A family study of the variability of pulmonary function in alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Quantitative phenotypes. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990, 142:1015–1021.

Visser M, Bouter LM, McQuillan GM, Wener MH, Harris TB: Elevated C-reactive protein levels in overweight and obese adults. JAMA 1999, 282:2131–2135.

Moshage H: Cytokines and the hepatic acute phase response. J Pathol 1997, 181:257–266.

Engstrom G, Janzon L, Berglund G, Lind P, Stavenow L, Hedblad B, Lindgarde F: Blood pressure increase and incidence of hypertension in relation to inflammation-sensitive plasma proteins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002, 22:2054–2058.

Acknowledgements

Research support provided by the Olga-Mayenfisch Stiftung Zürich; the Swiss National Science Foundation (grants no 4026–28099, 3347CO-108796, 3247BO-104283, 3247BO-104288, 3247BO-104284, 32–65896.01, 32–59302.99, 32–52720.97, 32–4253.94), the Federal Office for Forest, Environment and Landscape, the Federal Office of Public Health, the Federal Office of Roads and Transport, the canton's government of Aargau, Basel-Stadt, Basel-Land, Geneva, Luzern, Ticino, Zurich, the Swiss Lung League, the canton's Lung League of Basel Stadt/Basel Landschaft, Geneva, Ticino and Zurich. Oliver Senn was a recipient of an ALTA fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

OS conducted the analysis and drafted the article. EWR, MI, AvE, CS, OB, EZ, UA, WB, TR, and NMPH contributed to the design of the study, the acquisition of data and interpretation of data. CS, EWR, TR, ML and NMPH also advised on the conduct of the analysis. All authors made important intellectual contributions during the drafting process and have given approval for the final version.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Senn, O., Russi, E.W., Schindler, C. et al. Circulating alpha1-antitrypsin in the general population: Determinants and association with lung function. Respir Res 9, 35 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-9-35

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-9-35