Abstract

Background

Mucin hypersecretion and mucus plugging in the airways are characteristic features of chronic respiratory diseases like cystic fibrosis (CF) and contribute to morbidity and mortality. In CF, Pseudomonas aeruginosa superinfections in the lung exacerbate inflammation and alter mucus properties. There is increasing evidence that n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) exhibit anti-inflammatory properties in many inflammatory diseases while n-6 PUFA arachidonic acid (AA) favors inflammatory mediators such as eicosanoids prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and leukotriene B4 (LTB4) that may enhance inflammatory reactions. This suggests that n-3 PUFAs may have a protective effect against mucus over-production in airway diseases. Therefore, we hypothesized that n-3 PUFAs may downregulate mucins expression.

Methods

We designed an absolute real-time PCR assay to assess the effect of a 5-week diet enriched either with n-3 or n-6 PUFAs on the expression of large mucins in the lungs of mice infected by P. aeruginosa.

Results

Dietary fatty acids did not influence mucin gene expression in healthy mice. Lung infection induced an increase of the secreted gel-forming mucin Muc5b and a decrease of the membrane bound mucin Muc4. These deregulations are modulated by dietary fatty acids with a suppressive effect of n-3 PUFAs on mucin (increase of Muc5b from 19-fold up to 3.6 × 105-fold for the n-3 PUFAs treated group and the control groups, respectively, 4 days post-infection and decrease of Muc4 from 15-fold up to 3.2 × 104-fold for the control and the n-3 PUFAs treated groups, respectively, 4 days post-infection).

Conclusion

Our data suggest that n-3 PUFAs enriched diet represents an inexpensive strategy to prevent or treat mucin overproduction in pulmonary bacterial colonization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic Gram-negative pathogen known for its environmental versatility and ability to cause diseases in susceptible individuals. P. aeruginosa is an inhabitant of soil, water and vegetation but, unlike many environmental bacteria, can cause urinary, respiratory, and digestive tract infections usually restricted to hospitalized patients with predisposing conditions (device related infections, mechanical ventilation). Moreover, P. aeruginosa respiratory tract chronic infections are common in cystic fibrosis (CF) and other chronic lung conditions generating excessive inflammatory response leading to airway obstruction and structural lung damage [1].

Pseudomonas superinfections in CF, as well as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), are multifactorial involving innate host immunity, pathogen characteristics and mucus properties. Chronic inflammatory diseases are mainly characterized by an inappropriate production of inflammatory mediators and chronic inflammation, which is associated with tissue damage and organ dysfunction. There is evidence that n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) exhibit anti-inflammatory properties in many inflammatory diseases while n-6 PUFA arachidonic acid (AA) favors inflammatory mediators such as eicosanoids prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and leukotriene B4 (LTB4) that may enhance inflammatory reactions. Experimental data and clinical studies suggest that n-3 PUFAs represent potential therapeutic agents for inflammatory diseases (reviewed by Mori and Beilin [2]; James et al. [3]). For example, Shahar et al. reported that dietary intake of n-3 fatty acids and fish consumption play a protective effect in COPD [4]. In fact, n-3 PUFAs could improve not only inflammation but also diminish mucosal damage [5]. Concerning CF, Freedman et al. showed that a membrane lipid imbalance exists in both Cftr-/- mice and in subjects with cystic fibrosis [6–8]. This imbalance may play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of CF and could be corrected by oral administration of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).

One important factor in the morbidity and mortality of chronic airway diseases is the overproduction of mucus with altered rheologic properties (for review, see [9]), which may influence the first step of pathogen adhesion. For example, gland ducts of the airway epithelium become occluded with mucus during the first months in the CF fetus [10]. Mucins are heavily O-glycosylated proteins found in the mucus layer and responsible for its physical properties. These complex large molecules trap bacteria in the lung, and the ciliary beating draws the mucus layer up to the pharynx where normally it is swallowed (for reviews, see [11, 12]). Mucins are usually subdivided into two families. The first one is made of large monomeric mucins, which are located primarily, but not exclusively, at the cell surface. The other one is made of the five, large secreted gel-forming mucins MUC6, MUC2, MUC5AC, MUC5B and MUC19, which are conserved between human and mouse [13–15] and form oligomeric structures [9, 16, 17]. Among the identified mucins, the large anchored-mucin MUC4 and the two large gel-forming mucins MUC5B and MUC5AC seem highly expressed in normal and/or abnormal human lung while MUC2 is almost not detectable [18]. At the cellular level, MUC5AC is expressed in the goblet cells of main bronchi and bronchioles and MUC5B is expressed in bronchiolar epithelium and in submucosal gland epithelium while MUC4 transcripts are detected in the epithelium of main bronchi and bronchioles [19–21]. While many studies have focused on gene regulation of both MUC2 and MUC5AC using mainly airway cell cultures and explants, regulation of MUC4 and MUC5B in airway diseases have been ignored to date.

In this study, we hypothesized that dietary intakes of n-3 PUFAs decrease mucin production in chronic airway diseases that likely decreases the mucus visco-elasticity and, on the other hand, that a diet enriched in n-6 PUFAs exacerbated mucin expression. We determined the mucin expression pattern in lung of healthy wild-type mice and then in vivo mucin regulation of Pseudomonas-infected mice that were fed for 5 weeks with a diet enriched in either n-3 PUFAs or n-6 PUFAs compared to a control rodent diet with equal fat content.

Methods

Mice

Five-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River (France) and housed five per cage in filter-capped cages with hardwood bedding. Cages are placed into a ventilated cabinet in a quiet room at the University of Lille on a 12:12 hour light/dark cycle and were kept at a constant room temperature (24°C). Animals were allowed to acclimatize for at least one week prior the start of the experimental procedure. They were randomized to be fed for 5 weeks with either a control diet (C), a diet supplemented with n-3 or n-6 PUFAs. Tap water and sterilized food were continuously available throughout the study. The three formulations used are identical to the AIN-93G [22] except that the soybean oil has been replaced by three isocaloric and iso-fat content mixtures (Table 1). Diet 1 is dominated by EPA and contains also lower amounts of other n-3 PUFAs (ALA, STA, DHA) while diet 2 is dominated by arachidonic acid (AA) (n-6 PUFAs). This study is a subset of the mice used in a recent publication [23]. All procedures were in accordance with the French Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and with the guidelines of the European Union.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Primer and TaqMan probe sequences were selected using the Primer3 Output program Technology [24] from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Primers and probes (Table 2) have been chosen within the 3'-end of mouse Muc cDNAs. To avoid amplification of contaminating genomic DNA, primers and/or the probes have been designed on different exons or overlap exon-exon junctions. To quantify mucin expression obtained by real-time PCR, we used the standard curve method. The 18s rRNA was chosen as an internal positive control. For each mucin studied and for the 18s gene, reverse-transcribed RNA extracted from mouse lung was amplified (see below) and amplification products were cloned into the 3957-bp pCR4-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, France). Isolation of plasmid DNA was carried out with the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen). Positive clones were reconfirmed by digestion with the EcoRI restriction enzyme and inserts sequenced on both strands on Licor 4000 using universal oligonucleotides. Serial dilutions of each Qiagen-purified plasmid with the cDNA insert were prepared and DNA concentrations measured using the spectrofluorometer TD-360 (Fisher-Bioblock, France) and the Hoechst 33258 dye. Serial dilutions of plasmid cDNAs were amplified by qPCR in duplicate reactions, and standard curves were created by plotting the log of the input plasmid cDNA quantity (ng) versus cycle threshold (Ct) values for Muc4, Muc5ac, Muc5b and the 18s (Figure 1) allowing to determine the copy number for each sample.

Graphical representation of linear regression analyses to validate the quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) assay. Dilutions of plasmid cDNA were amplified by qPCR in duplicate reactions, and standard curves were created by plotting the cycle threshold (Ct) values versus DNA quantity (Log quantity) in ng for 18s, Muc4, Muc5ac and Muc5b.

Preparation of the bacterial inoculum

The methodology was adapted from Cash et al. [25]. Briefly, P. aeruginosa (PAO1 strain) was incubated in 125 ml of tryptic soy broth at 37°C in a rotating shaking water bath for 8 hours. The culture was then washed twice, and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline. The resulting bacterial suspension was 1 × 109 CFU/ml. A sample of 1 mL of this suspension was mixed in agarose and mineral oil (Sigma Diagnoses, St Louis, USA) at 56°C. The resulting oil-agarose emulsion was cooled to obtain agar beads. Dilutions of the final suspension were cultured to determine the CFU of the final inoculum. Thirty mice (10 per group) were inoculated per batch of agarose beads.

Experimental infection

Mice were anesthetized with sevoflurane (Sevorane™, Abbott, UK), and placed in dorsal recumbency. Transtracheal insertion of a 24-G animal feeding needle was used to instill 60 μL of a 1:4 dilution of the agarose beads (2 × 105 CFU/mouse). The mice were then allowed to recover. The inoculation of mice is a critical step [26] and for a better reliability a single operator conducted it. After instillation, mice were observed daily for clinical signs, such as posture and ambulation. Two experimentally infected mice were killed before the end of the experiment due to their poor ambulation and visual sign of painful posture. A few other infected mice died during the night and their carcass eliminated whereas no mice inoculated with sterile beads died.

Quantitative bacteriology

All mice were sacrificed using carbon dioxide followed by cervical dislocation. The lungs were excised aseptically on the first, the fourth or the seventh day after the inoculation or just after 5 weeks of diet (control mice, day 0). These lungs were then homogenized in PBS buffer, and the samples were cultured quantitatively by serial dilution on BCP agar plates (Biomerieux laboratories, Lyon, France). The plates were incubated at 37°C and P. aeruginosa colonies were counted after 24 h.

Expression of Muc genes

Uninfected and PAO1 instilled mice were sacrificed after 1, 4, or 7 days post- infection by cervical dislocation. The lungs were collected, washed into sterile PBS, rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted using TriReagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Euromedex, France) following manufacturer's protocol followed by precipitation in ethanol and resuspension in ribonuclease-free water. Single-stranded cDNA was generated from 2 μg of total RNA using the First -Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Clontech, Ozyme, France) and random hexamers according to the manufacturer's instructions. The 20 μL of cDNA was diluted with 80 μL of DEPC-water. Duplex PCR amplification was carried out in 25-μL reaction volumes containing 2 μL of the first strand cDNA, 10 pmol of each primer for a given mucin studied, 5 pmol of each mucin probe and 2× TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) containing 1 pmol of the 18s-primers (sense and antisense), 5 pmol of the 18s-probe (5' Vic reporter dye), 5,6-carboxy-x-rhodamine (ROX), the Taq DNA polymerase and the requisite buffers. Probes (Applied Biosystems, France) were labeled with 6-carboxy-fluorescein phosphoramidite (FAM) at the 5' end and as quencher 6-carboxy-tetramethyl-rhodamine (TAMRA) at the 3' end. The fluorescence intensity of the reporter label was normalized to the rhodamine derivative ROX as a passive reference label present in the buffer solution. The system generated a kinetic amplification plot based upon the normalized fluorescence. Amplifications were performed on the ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative analysis was conducted using an ABI7700 Real-Time Detection System. The PCR reaction ran for 45 cycles of a two-step PCR amplification (95°C for 10 minutes and 60°C for 1 minute). All reactions were run in triplicate. Negative controls were carried out with water instead of cDNA.

Data and statistical analysis

cDNA copies of Muc transcripts were adjusted with the number of cDNA copies for the 18s and Log transformed values were represented (Figures 2, 3, 4). For PAO1-inoculated experiment (Figure 4), each measured value has been divided by the median of the counterpart group of mice inoculated with sterile agarose beads. Comparisons were analyzed using the statistical package StatXact® 6.0 (Cytel Studio) for exact nonparametric inference. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney one-sided p-values were calculated to compare differences between groups (between diets for each day and between days for each diet) and given in Figures 3, 4. P values are given in 2 × 2 tables on figures 3 and 4. Correlations between variables were calculated by using Spearman's rank correlation tests (r s) with the Monte Carlo option. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Gene expression analysis in lung by absolute qPCR of mouse Muc4, Muc5ac and Muc5b transcripts normalized with the 18s. Five healthy mice fed with the control diet for 5 weeks were used in each group. Ratios between the absolute amounts of the three Muc copy numbers and the 18s copy number is given in Log10 (Muc/18s)+11 due to the high difference between the Muc4 level expression and the two other Mucs gene expression levels.

Effect of the diet on the mouse Muc4, Muc5b and Muc5ac gene expressions of mice inoculated with sterile agarose beads. Values represent the Log10 copy number of each Muc transcript normalized with the 18s (log(Muc/18s))+11. Exact P-values were calculated to compare the effect between days for a given diet (ω3: n-3 PUFA treated group; C: control diet group; ω6: n-6 PUFA treated group) or between diets for a given day. Significant P-values are given in 2 × 2 tables.

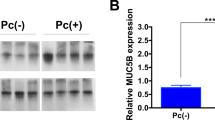

Suppressive effect of an n-3 PUFAs enriched diet on the Muc gene expression of mice infected with P. aeruginosa. Values represent 6+log [(Muc of infected lung/18s of infected lung)/median(Muc of sterile beads/18s of sterile beads)]. Exact P-values were calculated to compare the effect between days for a given diet (ω3: n-3 PUFA treated group; C: control diet group; ω6: n-6 PUFA treated group) or between diets for a given day. Significant P-values are given in 2 × 2 tables.

Results

Mice were fed for 5 weeks prior P. aeruginosa (PAO1) infection with either a control diet (C) or a diet enriched with n-3 PUFAs or n-6 PUFAs (Table 1). This model mimics chronic lung infection in mice [25–28] as they lost weight after infection and bacteria could still be recovered at the termination of the study [23]. Bacterial clearance was analyzed over the 7 days of the experiment. The number of bacteria dropped over time in each group, and a comparable pattern was observed for each diet with no difference between the three groups [23].

To study mucin gene expression, we designed a fluorescence based PCR assay to determine an exact and absolute quantification of the mouse Muc5b, Muc5ac and Muc4 RNAs allowing comparisons of expression levels between the three different Muc genes. The housekeeping gene 18s was used as an internal positive control and to normalize each Muc gene expression level. The cDNA amplification products of mouse Muc4 (102 bp ; table 2), Muc5b (133 bp), Muc5ac (118 bp) and mouse 18s (187 bp) were cloned into the pCR4 plasmid vector. Serial dilutions of these cDNA plasmids were used to establish standard curves, and cycle threshold (Ct) values were determined to be between 8 and 13 (Figure 1). Ct values represent the number of amplification cycles required to produce a specific amount of fluorescence during the exponential phase of the quantitative PCR. Consequently, the higher the Ct value, the lower the concentration of the template being amplified. Ct values increased linearly with decreasing input cDNA plasmids. The average r 2 values for the 18s and the Muc genes assayed were greater than 0.98 (Figure 1). Efficiency of our Muc PCR assays varied (mean slope) from -3.10 to -3.27 while the efficiency of the commercially 18s was -2.47.

We performed qPCR on 15 mice that were non-inoculated (day 0, 5 mice/group), 45 inoculated with sterile beads and sacrificed at days 1, 4 and 7 (5 mice/group/day) and on infected lung tissues from mice of the n-3 PUFAs, control and n-6 PUFAs diet groups that were killed at days 1 (5, 6 and 6 mice, respectively), 4 (6 mice/group) or 7 (11, 6 and 3 mice, respectively). Figure 2 shows the relative copy numbers of Muc4, Muc5b and Muc5ac normalized with the 18s for mice fed with the three diets. The expression level of Muc4 in lung of healthy mice was higher than the expression levels of both Muc5b and Muc5ac RNAs. Medians of normalized Muc genes for control groups were 1.8 × 10-3, 2 × 10-11 and 2 × 10-6 for Muc4, Muc5b and Muc5ac, respectively, pointing out the high level of Muc4 in comparison with the two secreted gel-forming mucins. We did not observe any significant impact of the diet on the regulation of the three Muc genes studied.

Inoculation with sterile agarose beads induced a significant downregulation of Muc4 and an upregulation of Muc5b (Figure 3). At day 7, the level of Muc4 increased towards its baseline level (day 0). For each day, the diet has no impact on the two mucins gene expression except at day 7 on the Muc5b transcripts where the level of expression is n-3 < n-6 (p < 0.05). Concerning the Muc5ac gene, levels of the RNA transcript between the groups were similar over time with the exception for the n-6 PUFAs treated group between days 0/4 and 0/7 where the AA-enriched diet played an enhanced effect. In conclusion, the diet has almost no effect on mucin gene expression of mice inoculated with sterile agarose beads.

We next examined whether diet had an impact on Pseudomonas-infected mice. For each group at each day, the Log10 transformed value measured was normalized with the mucin median value of the corresponding group where mice were inoculated with sterile agarose beads. Membrane-bound Muc4 expression decreased over time (Figure 4). On the fourth day after infection, the n-3 PUFAs enriched diet has a high suppressive effect on the level expression of Muc4 (p < 0.005). Muc5b expression increased significantly for the n-3 PUFAs treated group between days 1 and 4. The expression levels tend to go down at day 7 with a statistically decrease for the control diet group. At days 1 and 4, the peak of expression of the large secreted gel-forming mucin Muc5b was higher for the control group diet in comparison with the n-3 PUFAS treated group suggesting a suppressive effect of n-3 PUFAs on inoculated mice. P. aeruginosa lung infection did not appear to impact Muc5ac expression over time, regardless of diet. Level of expression is higher at day 1 for the n-3 PUFAs treated group comparing to the two other groups. This peak is followed by a decrease at day 4. Additionally, we noticed a large dispersion of samples of the n-3 PUFAs treated group for the three Mucs studied at day 7.

Associations between the three-studied Muc gene expressions were assessed using Spearman's s rank correlation coefficient. There was no statistically significant association between Muc4 and either Muc5ac or Muc5b at day 0 and at day 1. However, Spearman's rank correlation indicated a strong positive correlation at day 4 (rs = 0.67 ; p < 0.004 and rs = 0.84 ; p < 0.0001), for Muc4/5ac and Muc4/5b, respectively and at day 7 (rs = 0.9 ; p < 0.0001 and rs = 0.76 ; p < 0.0001) for Muc4/5ac and Muc4/5b, respectively. Concerning Muc5ac and Muc5b, the two gene expressions were statistically correlated at days 1 and 7 (rs = -0.57 ; p < 0.03 and rs = 0.81 ; p < 0.0001, respectively). Spearman's rank-order correlation coefficient did not show any relationships between the bacteria number and the three Muc genes except for Muc4 at day 7 (rs = -0.48 ; p < 0.04).

Discussion

Mucus hypersecretion, viscoelastic alteration and mucin overproduction are the hallmarks of many lung diseases such as CF [9, 17, 29] where P. aeruginosa is the principal pathogenic microorganism. The properties of the mucus layer are dictated by the water content and the mucin layer composition. MUC5AC, MUC5B and MUC4, which are conserved mucins between human and rodent [30, 31], are three predominant large mucins expressed in the lung. Many studies have focused on MUC5AC and MUC2 regulation in airway diseases using mainly airway cell and explant cultures [32–34] while the expression of the oligomeric mucin MUC5B and the membrane-bound mucin MUC4 have not yet been investigated. However, biochemical studies on human samples have shown that the aberrant physical properties of the mucus gel obstructing the airways from an individual that died in status asthmaticus are due to MUC5B and not MUC5AC [35, 36]. Many, if not all, investigations that used human secretions encountered biased results due to the false status of the patient studied, non-controlled environmental parameters or difficulties to analyze in vivo mucins production pointing out the benefit of animal models in CF studies. Using a precise and reliable assay we (i) determined here the relative expression of lung mucins of healthy mice, mice inoculated with sterile agarose beads and mice infected with P. aeruginosa and (ii) examined the effects of a diet enriched either with n-3 PUFAs or n-6 PUFAs on mucin expression following experimental mouse lung inoculation.

The model of infection we used does not mimic perfectly a chronic lung infection, as the number of bacteria declined over time and several lung mice that were inoculated with PA01 were culture-negative at day 7. However, this model is still the best one available in mice [27, 28]. A single operator trained for delivering a uniformity of bead preparations from experiment to experiment and for inoculating mice performed these two steps in order to minimize caveats associated with this model (e.g., variability inherent to operator for the instillation procedure, in making agarose beads [26]).

To follow the mouse Muc gene expression that likely reflects protein synthesis [5, 37, 38], we designed an absolute PCR quantification assay instead of the often-used comparative Ct method. One advantage of the absolute qPCR is that the efficiency of the housekeeping gene used as an internal reference and the target Muc genes must not be necessary identical. Furthermore, absolute qPCR allows a more precise and sensitive RNA quantification with reliability between different laboratories. In our mouse model, we followed Muc5b, Muc5ac and Muc4 while the Muc2 messenger was barely undetectable in lung tissue and did not show any variation prior or after instillation by sterile or PAO1-laden agarose beads (data not shown). This study showed for the first time that diet has an impact and could modulate lung mucin gene expression in an in vivo model of bacterial infection.

As it is well-known, rodent models only partially resemble the native architecture and abundance of submucosal glands in the human airways [39], it is therefore not surprising that Muc5b is almost undetectable using qPCR in the lungs of healthy mice. In human, it has been reported that MUC5AC expression, measured using real-time RT-PCR, is much higher than both MUC5B and MUC4 in homogenates of endobronchial biopsies from healthy subjects or subjects with asthma [40]. Here we showed in mouse lung that Muc4 is highly expressed in comparison to Muc5b and Muc5ac. This could be due to the species studied and/or the "healthy" status of the human biopsies used by others and/or the RT-PCR quantification strategy. Moreover, we chose an absolute quantification method using primers directed at the 3'-end of the Muc genes with oligonucleotides belonging to different exons while in the previous work authors quantified MUC4 expression using a relative qPCR strategy with oligonucleotides chosen within exon 2 of the gene.

Yanagihara et al. showed that intratracheal injection of 100 μg of P. aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced mucus cell metaplasia. Northern blot analysis using 3 mice showed an increase of the Muc5ac messenger with a peak at day 4 followed by a decrease of Muc5ac RNA [41]. In this present study, we did not observe major modification in the Muc5ac expression with the exception of an upregulation at day 7 for the n-6 PUFAs treated group inoculated with sterile beads (Figure 3).

PAO1 lung inoculation induced two opposite expression patterns of Muc5b and Muc4: Muc5b is highly upregulated with a peak at day 4 showing a suppressive effect of n-3 PUFAs on the Muc5b response to the infection while Muc4 expression decreased to the lowest level at days 1 or 4 for sterile beads and at day 7 for Pseudomonas-laden agarose beads. In parallel with the bacterial clearance by ciliary transport, expression of Muc5b decreased almost to baseline levels on day 7. The increase of Muc5b messenger may reflect either a transdifferentiation of ciliated cells to a secretory phenotype or differentiation of hypothetical progenitor cells [38].

It is now well known that consumption of fish oil containing n-3 PUFAs reduces the risk of many human diseases [42]. Dietary lipid manipulation may affect different immune parameters and the immune modulation induced by dietary fatty acids may be applied by the improvement of inflammatory disorders. A dietary immune regulation with a defined blend of specific long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid species should represent an interesting alternative to immune suppressive molecules, like corticosteroids, which often causes side-effects. Compared to other studies that used fish oil supplementation or uncontrolled vegetable oil extractions, we used two fat isocaloric and isofat content blends. One is dominated by eicosapentanoic acid (EPA) -but contained other n-3 PUFAs- that act as a competitive inhibitor of AA conversion to the pro-inflammatory key mediators PGE2 and LTB4 while the other diet is dominated by AA, which gives rise to PGE2 and LTB4 (reviewed by James et al. [3]). On the other hand, PUFAs are also candidates to directly influence gene expression that is connected to diseases and then to enhance epithelial protection during inflammation and/or pathogenic bacterial colonization. PUFAs integrated into cellular membranes could also influence cell function and membrane integrity as DHA and AA compete for the same elongation and desaturation enzymes and for the site of esterification of phospholipids. The switching of AA by DHA leads to a change in regulatory fluidity and membrane trafficking [43, 44].

The present study shows that dietary PUFAs did not influence mucin gene expression in the lungs of healthy mice after 5 weeks of diet (control mice and mice inoculated with sterile beads). As the three experimental diets only differed in their content of PUFAs, differences in fatty acids are most likely responsible for the regulation of lung mRNA transcripts of mucins after infection by P. aeruginosa in agreement with Spearman's rank correlation. The regulation is modulated by the PUFAs intake with a suppressive effect of n-3 PUFAs on mucin upregulation and/or possibly an enhanced effect on the same Muc genes by n-6 PUFAs. This work is a part of a larger study and it should be noted that mice exposed to high n-3 PUFAs intakes and infected by P. aeruginosa exhibited a lower mortality than mice from the control group and mice fed with the diet rich in n-6 PUFAs [23] at day 4 after infection while survival rate of mice inoculated with sterile agarose beads was 100% at day 7 regardless of diet. One limit of our study is that a few mice inoculated with PAO1 died before day 4 (more in the control group and n-6 treated PUFAS group compared to n-3 PUFAs treated group) and were therefore not studied rending interpretations difficult for day 1.

Taken together, these data suggest that dietary intake of n-3 PUFAs reduces the lung damage by P. aeruginosa. Nieto et al. draw a similar conclusion about n-3 PUFAs and intestinal damages in rats with experimental ulcerative colitis where n-6 PUFAs enhanced tissue responsiveness to cytokines and n-3 PUFAs had opposite effects [5]. This suggests that overproduction of large mucins that likely leads to airway mucus obstruction in Pseudomonas aeruginosa chronic pneumonia may be counterbalanced by a n-3 PUFAs enriched diet. Further studies will be needed to confirm the relationship between mucin expression levels and mucus obstruction and to determine if the beneficial suppressive effects of dietary n-3 PUFAs on mucin expression used a direct or pro-inflammatory cytokine-dependent mechanism.

Conclusion

In summary, lung infection by P. aeruginosa induced a disregulation of the large mucins Muc5b and Muc4. These modifications of mucin expression are modulated by dietary long-chain fatty acids with a beneficial suppressive effect of n-3 PUFAs confirming our first hypothesis. This strongly supports that malnutrition can compromise pulmonary defenses against P. aeruginosa colonization [45].

Abbreviations

- CF:

-

cystic fibrosis

- COPD:

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Ct :

-

cycle threshold

- FA:

-

fatty acids

- S-FA:

-

total saturated FA

- MUFA:

-

mono-unsaturated FA

- PUFAs:

-

polyunsaturated fatty acids

- ALA:

-

alpha-linolenic acid

- STA:

-

stearidonic acid

- EPA:

-

eicosapentaenoic acid

- DHA:

-

docosahexaenoic acid

- LA:

-

linoleic acid

- GLA:

-

gamma-linolenic acid

- AA:

-

arachidonic acid

- LPS:

-

lipopolysaccharide

References

Davis PB, Drumm M, Konstan MW: Cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996, 154:1229–1256.

Mori TA, Beilin LJ: Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammation. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2004, 6:461–467.

James MJ, Gibson RA, Cleland LG: Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory mediator production. Am J Clin Nutr 2000, 71:343S-348S.

Shahar E, Folsom AR, Melnick SL, Tockman MS, Comstock GW, Gennaro V, Higgins MW, Sorlie PD, Ko WJ, Szklo M: Dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and smoking-related chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 1994, 331:228–233.

Nieto N, Torres MI, Rios A, Gil A: Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids improve histological and biochemical alterations in rats with experimental ulcerative colitis. J Nutr 2002, 132:11–19.

Freedman SD, Katz MH, Parker EM, Laposata M, Urman MY, Alvarez JG: A membrane lipid imbalance plays a role in the phenotypic expression of cystic fibrosis in cftr(-/-) mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96:13995–14000.

Freedman SD, Weinstein D, Blanco PG, Martinez-Clark P, Urman S, Zaman M, Morrow JD, Alvarez JG: Characterization of LPS-induced lung inflammation in cftr-/- mice and the effect of docosahexaenoic acid. J Appl Physiol 2002, 92:2169–2176.

Freedman SD, Blanco PG, Zaman MM, Shea JC, Ollero M, Hopper IK, Weed DA, Gelrud A, Regan MM, Laposata M, Alvarez JG, O'Sullivan BP: Association of cystic fibrosis with abnormalities in fatty acid metabolism. N Engl J Med 2004, 350:560–569.

Thornton DJ, Sheehan JK: From mucin to mucus: toward a more coherent understanding of this essential barrier. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2004, 1:54–61.

Ornoy A, Arnon J, Katznelson D, Granat M, Caspi B, Chemke J: Pathological confirmation of cystic fibrosis in the fetus following prenatal diagnosis. Am J Med Genet 1987, 28:935–947.

Lamblin G, Degroote S, Perini JM, Delmotte P, Scharfman A, Davril M, Lo-Guidice JM, Houdret N, Dumur V, Klein A, Rousse P: Human airway mucin glycosylation: a combinatory of carbohydrate determinants which vary in cystic fibrosis. Glycoconj J 2001, 18:661–684.

Ramphal R, Arora SK: Recognition of mucin components by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Glycoconj J 2001, 18:709–713.

Chen Y, Zhao YH, Kalaslavadi TB, Hamati E, Nehrke K, Le AD, Ann DK, Wu R: Genome-wide search and identification of a novel gel-forming mucin MUC19/Muc19 in glandular tissues. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004, 30:155–165.

Culp DJ, Latchney LR, Fallon MA, Denny PA, Denny PC, Couwenhoven RI, Chuang S: The gene encoding mouse Muc19: cDNA, genomic organization and relationship to Smgc. Physiol Genomics 2004, 19:303–318.

Desseyn JL, Laine A: Characterization of mouse muc6 and evidence of conservation of the gel-forming mucin gene cluster between human and mouse. Genomics 2003, 81:433–436.

Dekker J, Rossen JW, Buller HA, Einerhand AW: The MUC family: an obituary. Trends Biochem Sci 2002, 27:126–131.

Rose MC, Voynow JA: Respiratory tract mucin genes and mucin glycoproteins in health and disease. Physiol Rev 2006, 86:245–278.

Fahy JV: Goblet cell and mucin gene abnormalities in asthma. Chest 2002, 122:320S-326S.

Sharma P, Dudus L, Nielsen PA, Clausen H, Yankaskas JR, Hollingsworth MA, Engelhardt JF: MUC5B and MUC7 are differentially expressed in mucous and serous cells of submucosal glands in human bronchial airways. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1998, 19:30–37.

Reid CJ, Gould S, Harris A: Developmental expression of mucin genes in the human respiratory tract. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1997, 17:592–598.

Hovenberg HW, Davies JR, Carlstedt I: Different mucins are produced by the surface epithelium and the submucosa in human trachea: identification of MUC5AC as a major mucin from the goblet cells. Biochem J 1996,318(Pt 1):319–324.

Reeves PG: Components of the AIN-93 diets as improvements in the AIN-76A diet. J Nutr 1997, 127:838S-841S.

Pierre M, Husson MO, Leberre R, Desseyn JL, Galabert C, Beghin L, Beermann C, Dagenais A, Berthiaume Y, Cardinaud B, Barbry P, Gottrand F, GUERY BP: Omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids improve host response in chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007, 00337.

Rozen S, Skaletsky H: Primer3 on the WWW for General Users and for Biologist Programmers. In Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols. Edited by: Krawetz S, Misener S. Totowa, NJ; 1999:365–386.

Cash HA, Woods DE, McCullough B, Johanson WG Jr, Bass JA: A rat model of chronic respiratory infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am Rev Respir Dis 1979, 119:453–459.

van Heeckeren AM, Schluchter MD: Murine models of chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection. Lab Anim 2002, 36:291–312.

van Heeckeren AM, Walenga R, Konstan MW, Bonfield T, Davis PB, Ferkol T: Excessive inflammatory response of cystic fibrosis mice to bronchopulmonary infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Invest 1997, 100:2810–2815.

van Heeckeren AM, Tscheikuna J, Walenga RW, Konstan MW, Davis PB, Erokwu B, Haxhiu MA, Ferkol TW: Effect of Pseudomonas infection on weight loss, lung mechanics, and cytokines in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 161:271–279.

Perez-Vilar J, Boucher RC: Reevaluating gel-forming mucins' roles in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2004, 37:1564–1577.

Chen Y, Zhao YH, Wu R: In silico cloning of mouse Muc5b gene and upregulation of its expression in mouse asthma model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 164:1059–1066.

Desseyn JL, Clavereau I, Laine A: Cloning, chromosomal localization and characterization of the murine mucin gene orthologous to human MUC4. Eur J Biochem 2002, 269:3150–3159.

Kohri K, Ueki IF, Shim JJ, Burgel PR, Oh YM, Tam DC, Dao-Pick T, Nadel JA: Pseudomonas aeruginosa induces MUC5AC production via epidermal growth factor receptor. Eur Respir J 2002, 20:1263–1270.

Li D, Gallup M, Fan N, Szymkowski DE, Basbaum CB: Cloning of the amino-terminal and 5'-flanking region of the human MUC5AC mucin gene and transcriptional up-regulation by bacterial exoproducts. J Biol Chem 1998, 273:6812–6820.

Shao MX, Ueki IF, Nadel JA: Tumor necrosis factor alpha-converting enzyme mediates MUC5AC mucin expression in cultured human airway epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003, 100:11618–11623.

Sheehan JK, Howard M, Richardson PS, Longwill T, Thornton DJ: Physical characterization of a low-charge glycoform of the MUC5B mucin comprising the gel-phase of an asthmatic respiratory mucous plug. Biochem J 1999,338(Pt 2):507–513.

Sheehan JK, Richardson PS, Fung DC, Howard M, Thornton DJ: Analysis of respiratory mucus glycoproteins in asthma: a detailed study from a patient who died in status asthmaticus. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1995, 13:748–756.

Basbaum C, Lemjabbar H, Longphre M, Li D, Gensch E, McNamara N: Control of mucin transcription by diverse injury-induced signaling pathways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999, 160:S44-S48.

Rose MC, Nickola TJ, Voynow JA: Airway mucus obstruction: mucin glycoproteins, MUC gene regulation and goblet cell hyperplasia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2001, 25:533–537.

Pack RJ, Al Ugaily LH, Morris G: The cells of the tracheobronchial epithelium of the mouse: a quantitative light and electron microscope study. J Anat 1981, 132:71–84.

Ordonez CL, Khashayar R, Wong HH, Ferrando R, Wu R, Hyde DM, Hotchkiss JA, Zhang Y, Novikov A, Dolganov G, Fahy JV: Mild and moderate asthma is associated with airway goblet cell hyperplasia and abnormalities in mucin gene expression. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 163:517–523.

Yanagihara K, Seki M, Cheng PW: Lipopolysaccharide Induces Mucus Cell Metaplasia in Mouse Lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2001, 24:66–73.

Sidhu KS: Health benefits and potential risks related to consumption of fish or fish oil. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2003, 38:336–344.

Stillwell W, Jenski LJ, Crump FT, Ehringer W: Effect of docosahexaenoic acid on mouse mitochondrial membrane properties. Lipids 1997, 32:497–506.

Ehringer W, Belcher D, Wassall SR, Stillwell W: A comparison of the effects of linolenic (18:3 omega 3) and docosahexaenoic (22:6 omega 3) acids on phospholipid bilayers. Chem Phys Lipids 1990, 54:79–88.

Yu H, Nasr SZ, Deretic V: Innate lung defenses and compromised Pseudomonas aeruginosa clearance in the malnourished mouse model of respiratory infections in cystic fibrosis. Infect Immun 2000, 68:2142–2147.

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by the French Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM), Numico Research (2003–2005) and two grants from the French Cystic Fibrosis association "Vaincre la Mucoviscidose" (JLD, FC0203 and FG, II00225).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

DT carried out the molecular genetic studies and helped to draft the manuscript. MP and MOH were involved in acquisition and interpretation of bacterial data. DD performed the nucleotide sequencing, RNA extraction and helped in performing qPCR. LB assisted in experimental design and statistic analyses. CG intellectually supported the research, and critically revised the manuscript. FG and CB supervised the research and analysis and critically revised the manuscript. BG participated in the design of the study, in the animal instillation and revised the draft. JLD conceived the study, participated in its design and in molecular biology experiments and drafted the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tetaert, D., Pierre, M., Demeyer, D. et al. Dietary n-3 fatty acids have suppressive effects on mucin upregulation in mice infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Respir Res 8, 39 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-8-39

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-8-39