Abstract

Background

The rate of decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) is representative of the natural history of COPD. Sparse information exists regarding the associations between the magnitude of annualised loss of FEV1 with other endpoints.

Methods

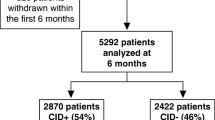

Retrospective analysis of UPLIFT® trial (four-year, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of tiotropium 18 μg daily in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], n = 5993). Decline of FEV1 was analysed with random co-efficient regression. Patients were categorised according to quartiles based on the rate of decline (RoD) in post-bronchodilator FEV1. The St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) total score, exacerbations and mortality were assessed within each quartile.

Results

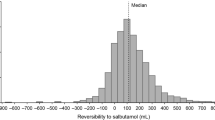

Mean (standard error [SE]) post-bronchodilator FEV1 increased in the first quartile (Q1) by 37 (1) mL/year. The other quartiles showed annualised declines in FEV1 (mL/year) as follows: Q2 = 24 (1), Q3 = 59 (1) and Q4 = 125 (2). Age, gender, respiratory medication use at baseline and SGRQ did not distinguish groups. The patient subgroup with the largest RoD had less severe lung disease at baseline and contained a higher proportion of current smokers. The percentage of patients with ≥ 1 exacerbation showed a minimal difference from the lowest to the largest RoD, but exacerbation rates increased with increasing RoD. The highest proportion of patients with ≥ 1 hospitalised exacerbation was in Q4 (Q1 = 19.5% [tiotropium], 26% [control]; Q4 = 33.8% [tiotropium] and 33.1% [control]). Time to first exacerbation and hospitalised exacerbation was shorter with increasing RoD. Rate of decline in SGRQ increased in direct proportion to each quartile. The group with the largest RoD had the highest mortality.

Conclusion

Patients can be grouped into different RoD quartiles with the observation of different clinical outcomes indicating that specific (or more aggressive) approaches to management may be needed.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00144339

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

An accelerated loss of lung function relative to healthy individuals is a characteristic feature of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and has been used to define the natural history of the disease [1–3]. The seminal publication by Charles Fletcher and Richard Peto described a rate of loss of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) in patients with airflow obstruction ranging from 37 ± 8 mL/year in ex-smokers to 80 ± 6 mL/year in heavy smokers (> 15 cigarettes per day), with an overall effect of 64 ± 3 mL/year [2]. Of note, the data are based on a relatively small cohort (n = 792) followed in the 1960s (albeit over a relatively long time interval of 8 years), the population was restricted to men and there is no mention of medication washout or bronchodilator administration preceding spirometry. In addition, the authors describe a 'horse-racing' effect in which there is an inverse relationship to the degree of airflow limitation at baseline and rate of subsequent loss of FEV1, the ultimate consequence of which, if left unabated, would be disability and premature death. The 'Fletcher-Peto curve', illustrating the rate of loss over time, has been widely discussed and displayed in peer-reviewed publications. However, the associations of differing magnitudes of loss over time with health outcomes have not been thoroughly documented. Furthermore, inferences from several decades ago may not be currently applicable given the substantial changes that have occurred in the diagnosis and management of COPD [1].

The Understanding Potential Long-term Impacts on Function with Tiotropium (UPLIFT®) trial is a four-year randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of tiotropium 18 μg daily in COPD patients who were permitted to use all respiratory medications throughout the trial other than inhaled anticholinergics [4]. The co-primary outcomes were the rate of decline in pre- and post-bronchodilator FEV1. We have therefore conducted a post-hoc analysis of the UPLIFT® data and have attempted to categorise patients according to differing rates of decline in post-bronchodilator FEV1 to document associations with clinically important health outcomes (i.e. exacerbations and health-related quality of life [HRQoL]).

Methods

Study Design

The study design of the UPLIFT® trial has been previously published [4, 5]. In brief, UPLIFT® was a four-year, international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial that evaluated the efficacy and safety of tiotropium 18 μg daily administered via HandiHaler® (Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH, Ingelheim, Germany) in the treatment of COPD. All patients in the tiotropium and placebo (control) groups were permitted to use all respiratory medications other than inhaled anticholinergics, as prescribed, throughout the trial. A two- to four-week run-in period was followed by the randomisation visit, a visit at four weeks, and then clinic visits every 12 weeks for the duration of the trial. A washout visit in which patients were asked to administer ipratropium 40 μg four times daily was scheduled for 30 days following completion of randomised study drug.

The study was approved by ethics committees and institutional review boards and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Study Population

Men and women who were aged ≥ 40 years, had ≥ 10 pack-year history of smoking and had evidence of airflow limitation (defined by a post-bronchodilator FEV1 ≤ 70% predicted and an FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) ≤ 0.70) were included. Exclusion criteria included a history of asthma, pulmonary resection, unstable disease, recent myocardial infarction and recent hospitalisation for congestive heart failure. Other criteria are outlined in previous publications and were designed to exclude patients who might not reasonably be assumed to be able to complete the trial or had an underlying disease that would interfere with the interpretation of the study results [4, 5].

Procedures

Spirometry was performed according to American Thoracic Society criteria at baseline, four weeks and every six months following randomisation [6]. After screening, spirometry was performed prior to, and following, short-acting bronchodilator and study drug administration. Short-acting bronchodilators were administered sequentially (ipratropium bromide four actuations, albuterol four actuations 60 minutes later) with spirometry being performed 30 minutes following the last dose. HRQoL was measured using the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) at baseline and every six months [7]. Exacerbations were recorded on case report forms and were required to follow a standard definition as follows: an increase in or the new onset of more than one respiratory symptom (cough, sputum, sputum purulence, wheezing or dyspnea) lasting three days or more and requiring treatment with an antibiotic or a systemic corticosteroid. All adverse events were recorded throughout the period of study drug administration. In addition, investigators were requested to collect vital status information on patients who prematurely discontinued study medication during the four years of the trial.

Data Analysis

Spirometric variables (FEV1, FVC and slow vital capacity) and SGRQ were analysed using random-effects models. The decline of lung function over time was analysed with random co-efficient regression. Patients were categorised according to quartiles based on the annualised rate of post-bronchodilator FEV1 decline. As treatment intervention with tiotropium would potentially interact with the health outcomes measured, the analysis was stratified by treatment group. Hazard ratios for exacerbations, hospitalised exacerbations and death were determined using Cox regression. The numbers of exacerbations and associated hospitalisations were calculated using Poisson regression with adjustment for overdispersion and treatment exposure. Baseline data were not included in the FEV1 model.

Results

Demographics

A total of 4964 patients from the total population (n = 5993) had evaluable spirometry for evaluation of rate of decline of FEV1. The number of patients within each quartile by treatment group is as follows: Q1 (tiotropium 661, control 580), Q2 (tiotropium 645, control 596), Q3 (tiotropium 627, control 614), Q4 (tiotropium 621, control 620). Overall, the mean (standard error [SE]) post-bronchodilator FEV1 increased in the first quartile (Q1) by 37 (1) mL/year (Figure 1). The other quartiles showed annualised mean (SE) declines in FEV1 (mL/year) as follows: Q2 = 24 (1), Q3 = 59 (1) and Q4 = 125 (2). The corresponding rates for post-bronchodilator FVC were as follows: increase in Q1 = 41 (4), decreases in Q2, Q3 and Q4 (Q2 = 33 [4], Q3 = 81 [4] and Q4 = 179 [5]). The baseline characteristics of the population by quartiles of rate of decline in post-bronchodilator FEV1 are displayed in Table 1. Approximately 75% were men with an average age of 64 years. Overall, age, gender, respiratory medication use at baseline and SGRQ total score did not appear to distinguish groups, although the subjects in the highest quartile tended to be younger and more predominantly male. The largest rate of decline included the highest proportion of current smokers. Patients with the largest rate of decline had less severe lung disease on average at baseline as seen by FEV1, FVC and Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage (Table 2).

Health Outcomes

The proportion of patients with at least one exacerbation over four years showed a minimal difference from the lowest rate of decline (Q1 = 66.6% [tiotropium] and 73.3% [control]) to the largest rate of decline (Q4 = 73.8% [tiotropium] and 76.6% [control]) (Figure 2A). However, in general, there was an increased rate of exacerbations with increasing rate of decline in post-bronchodilator FEV1 (Table 3). The highest proportion of patients with at least one hospitalised exacerbation was in the group with the largest rate of decline (Q1 = 19.5% [tiotropium] and 26% [control], Q4 = 33.8% [tiotropium] and 33.1% [control]) (Figure 2B). Overall, the time to the first exacerbation and first hospitalised exacerbation was shorter with increasing rate of decline in FEV1 quartiles, although results were somewhat inconsistent, especially for patients in the third quartile in the control group (Table 4).

The annualised rate of decline in the SGRQ total score increased linearly with each quartile increase in the post-bronchodilator decline in FEV1 (Figure 3). The range was from an improvement over time in Q1 (control 0.55 [0.19] units, tiotropium 0.24 [0.17] units) to the largest worsening in the Q4 group (control 2.87 [0.19] units, tiotropium 2.66 [0.18] units). The pattern of treatment response throughout the trial is illustrated in Figure 4.

Mortality

There appeared to be no distinguishing pattern of risk of a fatal event among the first three quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3); however, the group with the largest rate of FEV1 decline (Q4) had the highest overall mortality rate (Figure 5). For all of the hazard ratios, the 95% confidence intervals included one.

Proportion of patients who died during treatment according to post-bronchodilator FEV 1 RoD quartiles. Protocol defined treatment period (1440 days). Data also include those patients who discontinued study drug. Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; CI, confidence interval; RoD, rate of decline.

Discussion

The four-year UPLIFT® trial provided data that permitted examination of associations of the magnitude of lung function decline with changes in the clinically relevant health outcomes of exacerbations, HRQoL and survival [4, 5]. In order to examine patterns, the annualised rate of loss of post-bronchodilator FEV1 was divided into quartiles. Other than smoking status, demographics and respiratory medication use appeared to be largely similar among groups; and the most prominent difference at baseline was lung function, which appeared to be least impaired in those with the most rapid loss in FEV1. In longitudinal analyses, the patterns associated with quartiles of increasing rate of decline in FEV1 indicated a relationship to an accelerated loss of HRQoL, increased rate of exacerbations, increased risk of a hospitalised exacerbation and increased risk of death.

COPD is described as a disease of progressive airflow limitation, for which the most described marker remains the serial measurement of FEV1 [1]. The publication by Fletcher and Peto placed FEV1 decline over time at the forefront of biomarkers that illustrate disease progression [2]. However, the utility of any biomarker is somewhat dependent on its predictive value or associations with other clinically important endpoints. In this regard, there are two main analytic approaches to FEV1, regardless of whether it is described as an absolute volume or as a percentage of predicted normal. The first approach is the static single-point measurement. While there is a clear relationship of FEV1 severity to subsequent mortality, the descriptions of which date back several decades [8, 9], composite measures such as the BODE index that have FEV1 as a part of the measure appear to have higher predictive values [10]. Additionally, other parameters such as comorbidities and serum markers should continue to be explored for associations with disease progression. Yet a single measurement of FEV1 is poorly associated with other health outcomes such as exercise tolerance and quality of life. This may relate to issues of a single measurement in a disease that is known to have substantial day-to-day or week-to-week variability. The second analytic approach is serial measurements over time examining the pattern of change (i.e. slope).

Most studies have described FEV1 decline in the context of the effects of cigarette smoking and cessation of exposure to cigarette smoke with minimal data being published on the associations of rate of decline in FEV1 with other health outcomes [3, 11]. The rate of loss of lung function over time was recently described in the Towards a Revolution in COPD Health (TORCH) trial [12]. The authors noted that an increased rate of decline was associated with more frequent exacerbations [12]. A rapid decline in FEV1 has been associated with more frequent exacerbations of COPD in other studies [13, 14] and severe exacerbations have been shown to be associated with premature death [15]. The remaining studies have used FEV1 as an outcome measure but have not described changes in FEV1 over time relative to changes over time in other outcomes [16–19].

Our current population showed that age and gender did not differ significantly among the quartiles of FEV1 decline. Indeed, it appears that physician's treatment patterns, as viewed by concomitant respiratory medication prescription, also did not distinguish patient groups, at least as defined by disease severity at baseline (GOLD stage). Continued smoking did show differences, which is entirely expected and also provides evidence that the subgroups are valid [20]. The most rapid loss was observed in patients who appeared to have somewhat milder disease, either by absolute FEV1, FEV1 percent predicted or FVC. This seems to be somewhat contrary to the 'horse-racing' effect described by Fletcher and Peto, but may highlight the need for earlier and aggressive intervention in patients with COPD [2]. There may be several possible explanations for the differences in our study and that of Fletcher and Peto as follows: (a) different populations (British coal miners vs. well characterized multinational representation), (b) sample size (larger in the UPLIFT trial), (c) survival (more likely to have severe disease in the UPLIFT trial due to advance in health care), and (d) environmental conditions (coal miners and likely higher levels of particulate exposure vs. current air quality standards). A consistency is seen with recent data that show improvements in outcomes with long-term pharmacotherapy in GOLD stage II patients (UPLIFT® and TORCH), as well as significant benefit in patients not previously receiving maintenance respiratory medication [4, 21, 22].

Certain limitations should be noted. The calculation of FEV1 decline was only continued while the patient received study drug and was not assessed following premature discontinuation of study drug. Premature discontinuation of study drug occurred in more control patients (45%) than tiotropium patients (36%). However, there was still substantial exposure to both study drugs during the trial with multiple measurements over years in most patients in the current analysis. Suissa describes the phenomenon of regression to the mean, which certainly could contribute to our findings; however, the inclusion of a data point closely following randomisation (i.e. at 30 days) should limit this [23]. Each treatment group needs to be considered independently since between-treatment comparisons are not valid, given that subgroups are based on outcomes (i.e. rate of decline in FEV1). Furthermore, there is a bias toward the more severe COPD patients preferentially in the tiotropium group continuing to completion, due to the effectiveness of the intervention, which created unequal groups as the trial progressed. Nevertheless, the pattern of association of quartiles to rate of decline in FEV1 can be observed within both treatment groups.

The study's strengths included the large sample size, the rather liberal inclusion criteria, the length of the trial and the rigorous nature of the data collection. The latter is particularly true of spirometry, which pre-specified a stringent protocol and involved standardised equipment, study specific software and a centralised review of all measurements.

The current results provide supportive evidence of the relevance of serial measurements in FEV1 over time. A rapid loss of lung function appears to identify a group at increased risk for more frequent exacerbations, severe exacerbations (i.e. hospitalised events), an accelerated loss of HRQoL and premature mortality. FEV1 measurement is simple, relatively inexpensive, widely available and well standardised with published normative values. COPD is a chronic disease and patients with COPD may be followed clinically for several decades. Identification of rapid decliners could be clinically useful since such patients may represent a unique subset of patients who require aggressive interventions. It is relevant to note that there can be marked heterogeneity between individuals regarding the absolute annual loss of lung function, which will be influenced by their genetic background and environmental factors.

Identification of patients with the most rapid decline in lung function, particularly in the early stages of COPD, would require a study of reproducibility of FEV1 and its decline in individual patients, possibly at short intervals (e.g. 3-6 monthly). Before translating to clinical practice, further research is needed regarding the reproducibility and patterns of rate of decline in individual patients. At a minimum, additional research is required to identify factors, other than continued exposure to noxious fumes and particulate matter (i.e. tobacco smoke), such as biomarkers and genetic patterns that can both predict a rapid decline and lead to novel approaches in treating such patients. Another issue to consider is whether rapid decliners represent a distinct subset of COPD. In an editorial, Rennard and Vestbo described an approach in which COPD can be considered an orphan disease requiring unique approaches to different forms of the disease [24]. Moreover, in another editorial, Reilly wrote about COPD being the sum of many small COPDs [25]. Whether this is the case for rapid or slow decliners remains to be determined.

Conclusion

The current data suggest that patients can be divided into different rates of decline with the observation of different clinical outcomes indicating that specific (or more aggressive) approaches to management are needed.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

analysis of variance

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- COPD:

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- FEV1:

-

forced expiratory volume in 1 second

- FVC:

-

forced vital capacity

- GOLD:

-

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

- HRQoL:

-

health-related quality of life

- ICS:

-

inhaled corticosteroids

- LABA:

-

long-acting β2 agonist

- GOLD:

-

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

- RoD:

-

rate of decline

- SGRQ:

-

St George's Respiratory Questionnaire

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- SE:

-

standard error

- TORCH:

-

Towards a Revolution in COPD: Health

- UPLIFT®:

-

Understanding Potential Long-Term Impacts on Function with Tiotropium.

References

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO workshop report. 2001, Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, (revised December 2009), (accessed 13 August 2010), [http://www.goldcopd.org]

Fletcher C, Peto R: The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. Br Med J. 1977, 1: 1645-1648. 10.1136/bmj.1.6077.1645.

Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Kiley JP, Altose MD, Bailey WC, Buist AS, Conway WA, Enright PL, Kanner RE, O'Hara P, et al: Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1. The Lung Health Study. J Am Med Assoc. 1994, 272: 1497-1505. 10.1001/jama.272.19.1497.

Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, Burkhart D, Kesten S, Menjoge S, Decramer M, for the UPLIFT investigators: A four year trial of tiotropium in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008, 359: 1543-1554. 10.1056/NEJMoa0805800.

Decramer M, Celli B, Tashkin DP, Pauwels RA, Burkhart D, Cassino C, Kesten S: Clinical trial design considerations in assessing long-term functional impacts of tiotropium in COPD: the UPLIFT trial. COPD. 2004, 1: 303-312. 10.1081/COPD-200026934.

Standardization of spirometry - 1994 update. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995, 152: 1107-1136.

Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P: A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St George's Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992, 145: 1321-1327.

IPPB Trial Group: Intermittent positive pressure breathing therapy of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 1983, 99: 612-620.

Anthonisen NR: Prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from multicenter clinical trials. Am Rev Resp Dis. 1989, 140: S95-S99. 10.1164/ajrccm/140.1.95.

Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, Casanova C, Montes de Oca M, Mendez RA, Pinto Plata V, Cabral HJ: The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Eng J Med. 2004, 350: 1005-1012. 10.1056/NEJMoa021322.

Kohansal R, Matinez-Camblor P, Agusti A, Buist AS, Mannino DM, Soriano JB: The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction revisited: an analysis of the Framingham offspring cohort. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2009, 180: 3-10. 10.1164/rccm.200901-0047OC.

Celli BR, Thomas NE, Anderson JA, Ferguson GT, Jenkins CR, Jones PW, Vestbo J, Knobil K, Yates JC, Calverley PM: Effect of pharmacotherapy on rate of decline of lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the TORCH study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008, 178: 332-338. 10.1164/rccm.200712-1869OC.

Donaldson GC, Seemungal TA, Bhowmik A, Wedzicha JA: Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2002, 57: 847-852. 10.1136/thorax.57.10.847.

Kanner RE, Anthonisen NR, Connett JE: Lower respiratory illnesses promote FEV(1) decline in current smokers but not ex-smokers with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the lung health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001, 164: 358-364.

Soler-Cataluna JJ, Martinez-Garcia MA, Román Sánchez P, Salcedo E, Navarro M, Ochando R: Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005, 60: 925-993. 10.1136/thx.2005.040527.

The Lung Health Study Research Group: Effect of inhaled triamcinolone on the decline in pulmonary function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2000, 343: 1902-9.

Pauwels RA, Löfdahl CG, Laitinen LA, Schouten JP, Postma DS, Pride NB, Ohlsson SV: Long-term treatment with inhaled budesonide in persons with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who continue smoking. European Respiratory Society Study on Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N Engl J Med. 1999, 340: 1948-1953. 10.1056/NEJM199906243402503.

Burge PS, Calverley PMA, Jones PW, Spencer S, Anderson JA, Maslen TK: Randomised, double blind placebo controlled study of fluticasone propionate in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the ISOLDE trial. Br Med J. 2000, 320: 1297-1303. 10.1136/bmj.320.7245.1297.

Decramer M, Rutten-van Mölken M, Dekhuijzen PN, Troosters T, van Herwaarden C, Pellegrino R, van Schayck CP, Olivieri D, Del Donno M, De Backer W, Lankhorst I, Ardia A: Effects of N-acetylcysteine on outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Bronchitis Randomized on NAC Cost-Utility Study, BRONCUS): a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005, 365: 1552-1560. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66456-2.

Tashkin DP, Celli B, Kesten S, Lystig T, Mehra S, Decramer M: Long-term efficacy of tiotropium in relation to smoking status in the UPLIFT trial. Eur Resp J. 2010, 35: 287-294. 10.1183/09031936.00082909.

Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, Ferguson GT, Jenkins C, Jones PW, Yates JC, Vestbo J, the TORCH investigators: Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Eng J Med. 2007, 356: 775-789. 10.1056/NEJMoa063070.

Troosters T, Celli B, Lystig T, Kesten S, Mehra S, Tashkin DP, Decramer M, UPLIFT Investigators: Tiotropium as a first maintenance drug in COPD: secondary analysis of the UPLIFT trial. Eur Resp J. 2010, 36: 65-73. 10.1183/09031936.00127809.

Suissa S: Lung function decline in COPD trials: bias from regression to the mean. Eur Resp J. 2008, 32: 829-831. 10.1183/09031936.00103008.

Rennard SI, Vestbo J: The many "small COPDs": COPD should be an orphan disease. Chest. 2008, 134: 623-627. 10.1378/chest.07-3059.

Reilly JJ: COPD and declining FEV1 - time to divide and conquer?. N Eng J Med. 2008, 359: 1616-1618. 10.1056/NEJMe0807387.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the editorial support and assistance with tables and figures of Natalie Dennis and Dr. Yamini Khirwadkar (PAREXEL MMS). This study was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Pfizer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Donald Tashkin has received: honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Dey Labs, AstraZeneca, Teva Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline; consultancy fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Dey Labs, Schering-Plough, AstraZeneca; grants from Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Dey, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Schering-Plough, Sepracor; and speaker bureau fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Dey Labs, Schering-Plough, and AstraZeneca. Bart Celli has received: honoraria and consultancy fees from Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and GlaxoSmithKline; and grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, Forest, and GlaxoSmithKline. Marc Decramer has received: honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca; consultancy fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and GlaxoSmithKline; grants from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline; and speaker bureau fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Nycomed, and Dompé. Steven Kesten is a previous employee of Boehringer Ingelheim. Steven Kesten is a current employee of, and holds shares in Uptake Medical Corp. Dacheng Liu is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim.

Authors' contributions

Drs MD, BC, DT, and SK (former employee of Boehringer Ingelheim and currently at Uptake Medical, Tustin, California) contributed to the design and conduct of the UPLIFT® trial. Dr L (Boehringer Ingelheim) provided statistical support. All authors contributed to the data analyses, the interpretation of the data and the composition of the manuscript and were involved in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kesten, S., Celli, B., Decramer, M. et al. Adverse health consequences in COPD patients with rapid decline in FEV1 - evidence from the UPLIFT trial. Respir Res 12, 129 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-12-129

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-12-129