Abstract

This paper is concerned with obtaining the approximate solution of a class of semi-explicit integral algebraic equations (IAEs) of index 1. A Jacobi collocation method is proposed for the IAEs of index 1. A rigorous analysis of the error bound in weighted -norm is also provided, which theoretically justifies the spectral rate of convergence while the kernels and the source functions are sufficiently smooth. The results of several numerical experiments are presented which support the theoretical results.

MSC:65R20, 45F15.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Consider the following system of integral equations:

where , are matrices, , are given , dimensional vector functions, and is a solution to be determined. Here, we assume that the data functions , () are sufficiently smooth such that and for all . The existence and uniqueness results for the solution of the system (1.1) have been discussed in [1].

The system (1.1) is a particular case of the general form of the integral algebraic equations (IAEs)

which has been introduced in [1], where , . An initial investigation of these equations indicates that they have properties very similar to differential algebraic equations (DAEs). In analogy with the theory of DAEs (see, e.g., [2]), Kauthen [3] in 2000 has called the system (1.1) the semi-explicit IAEs of index 1.

Coupled systems of integral algebraic equations (IAEs) consisting of the first and second kind Volterra integral equations (VIEs) arise in many mathematical modeling processes, e.g., the controlled heat equation which represents a boundary reaction in diffusion of chemicals [4], the two dimensional biharmonic equation in a semi-infinite strip [5, 6], dynamic processes in chemical reactors [7], and the deformed Pohlmeyer equation [8]. Also a good source of information (including numerous additional references) on applications of IAEs system is the monograph by Brunner [1].

As far as we know, there have been a few works available in the literature which has considered the theory of IAEs system. The existence and uniqueness results of continuous solution to linear IAEs system have been investigated by Chistyakov [9]. Gear in [10] defined the index notion of IAEs system by considering the effect of perturbation of the equations on the solutions. He has also introduced the index reduction procedure for IAEs system in [10]. Bulatov and Chistyakov [11] gave the existence and uniqueness conditions of the solution for IAEs systems with convolution kernels and defined the index notion in analogy to Gear’s approach. Further details of their investigation may be found in [12, 13]. Kauthen in [3] analyzed the spline collocation method and its convergence properties for the semi-explicit IAEs system (1.1). Brunner [1] defined the index-1 tractability for the IAEs system (1.1) and he also investigated the existence of a unique solution for this type of systems. Recently, the authors in [4] have defined the index-2 tractability for a class of IAEs and presented the Jacobi collocation method including the matrix-vector multiplication representation of the equation and its convergence analysis. The authors in [14] proposed the Legendre collocation method for IAEs of index 1 and obtained the posteriori error estimation.

It is well known that the classical Jacobi polynomials have been used extensively in mathematical analysis and practical applications, and play an important role in the analysis and implementation of the spectral methods. The main purpose of this work is to use the Jacobi collocation method to numerically solve the IAEs (1.1). We will provide a posteriori error estimate in the weighted -norm which theoretically justifies the spectral rate of convergence. To do so, we use some well-known results of the approximation theory from [15–17] including the Jacobi polynomials, the Gronwall inequality and the Lebesgue constant for the Lagrange interpolation polynomials.

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we carry out the Jacobi collocation approach for the IAEs system (1.1). A posteriori error estimation of the method in the weighted -norm as a main result of the paper is given in Section 3. Some numerical experiments are reported in Section 4 to verify the theoretical results obtained in Section 3. The final section contains conclusions and remarks.

2 The Jacobi collocation method

This section is devoted to applying the Jacobi collocation method to numerically solve the IAEs system (1.1). We first use some variable transformations to change the equation into a new system of integral equations defined on the standard interval , so that the Jacobi orthogonal polynomial theory can be applied conveniently. For simplicity, we will consider the IAEs system (1.1) with .

Let () be a weight function in the usual sense. As defined in [15, 18, 19], the set of Jacobi polynomials forms a complete orthogonal system, where is the space of functions with , and

For the sake of applying the theory of orthogonal polynomials, we use the change of variables:

to rewrite the IAEs system (1.1) as

where

We consider the discrete expansion of as follows:

where is a projection to the finite dimensional space and is the Jacobi polynomial such that

where the quadrature points are the Jacobi Gauss quadrature points, i.e., the zeros of , the normalization constant and the weights are given in [[18], p.231].

In the Jacobi collocation method, we seek a solution of the form

Inserting the discrete expansions (2.3) and (2.5) into (2.2), we obtain

where , and

By substituting the collocation points in the system (2.6) and employing the discrete representation (2.5), we obtain

and we let

then system (2.7) can be rewritten as

Now, the unknown coefficients and , are obtained by solving the linear system (2.8) and finally the approximate solutions and will be computed by substituting these coefficients into (2.5). Because the matrix of the coefficients of the linear system (2.8) is non-symmetric, when N is large, we can use some basic iterative methods to solve it, such as the generalized minimal residual (GMRES) method (see [[19], pp.48-60]), which is popular for solving non-symmetric linear systems.

3 Error estimation

In this section, we present a posteriori error estimate for the proposed scheme in the weighted -norm. Firstly, we recall some preliminaries and useful lemmas from [15].

Let be the space of all polynomials of degree not exceeding N, and . From [15], the inverse inequality concerning differentiability of the algebraic polynomials on the interval can be expressed in terms of -norm.

Lemma 3.1 (see [15])

Let , then for any integer , , there exists a positive constant C independent of N such that

From now on, to simplify the notation, we denote by and by . We also give some error bounds for the Jacobi system in terms of the Sobolev norms. The Sobolev norm and semi-norm of order , considered in this section, are given by

Lemma 3.2 (see [15])

Let , is the truncated orthogonal Jacobi series of u. The truncation error can be estimated as follows:

The following main theorem reveals the convergence results of the presented scheme in the weighted -norm.

Theorem 3.1 Consider the system of integral algebraic equation (2.2) where and the data functions , , , are sufficiently smooth and for all . Let be the Jacobi collocation approximation of which is defined by (2.5). Then the following estimates hold:

if N is sufficiently large, where (), .

Proof Similar to the idea in [14], we let

From systems (2.2) and (2.7), we obtain

Equations (3.8) and (3.9) can be written in the compact matrix representation:

with

and

Since , the inverse of the matrix exists and

Using the Gronwall inequality (see, e.g., [[20], Lemma 3.4]) on (3.10), we have

Here .

It follows from (3.4) that

Using (3.4), (3.3) for and the Hardy inequality [[21], Lemma 3.8], we obtain

and consequently

Also,

where is the Lagrange interpolation polynomial based on the Gauss quadrature nodes (see [19]). Therefore, we have

Moreover, using the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality [15], we have

By (3.4), we have

Now, we will make use of the result of Chen and Tang [[21], Lemma 3.4], which gives the Lebesgue constant for the Lagrange interpolating polynomials with the nodes of the Jacobi polynomials. Actually, the following relation holds:

So we obtain

Similarly,

It then follows from (3.1), (3.20), and (3.21) that

Similarly,

Using (3.2) and letting in (3.5), we have

Applying (3.3) for , we have

Similarly,

Finally, combining the above estimates and (3.11), the desired error estimates (3.6) and (3.7) are obtained. □

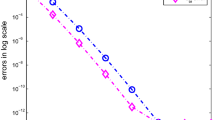

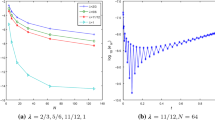

4 Numerical experiments

In this section, we consider some numerical examples in order to illustrate the validity of the proposed Jacobi collocation method. These problems are solved using the Jacobi collocation method for , . All the computations were performed using software Matlab®. To examine the accuracy of the results, errors are employed to verify the efficiency of the method. To find the numerical convergence order in the numerical examples, we assume that , where denotes the errors between the numerical and exact solution of the system and C denotes some positive constant. Thus, the convergence order p can be computed by .

Example 4.1 Consider the following linear system of IAEs of index 1:

where

and are chosen so that the exact solutions of this system are

Let and be the approximate and the exact solution of the system, respectively. The -norm of the errors and orders of convergence are given in Tables 1 and 2.

Example 4.2 Consider the following linear system of IAEs of index 1:

where

and are chosen so that the exact solutions of this system are

The computational results have been reported in Tables 3 and 4.

It can be seen from Tables 1 and 3 that the errors decay exponentially and the rates of convergence for are larger than those for . Tables 2 and 4 also shows that the orders of convergence for are higher than those for . In fact, it is noted that the differences of the convergence orders for and are about 2 from Tables 2 and 4. Although the exact solutions of Examples 4.1 and 4.2 are infinitely differentiable functions, it can be implied, from Theorem 3.1, that a conservative estimate of the numerical convergence order for system (1.1) is only 1. However, from numerical experiments, the numerical convergence order is much higher than 1.

Example 4.3 Consider the following linear system of IAEs:

where

and are chosen so that the exact solutions of this system are

Let u, v, w be the approximations of the exact solutions , , , respectively. The errors and orders of convergence for the proposed method with several values of N are reported in Tables 5 and 6. The results show that the methods are convergent with a good accuracy.

5 Conclusions

This paper studies the Jacobi collocation method for the semi-explicit IAEs system of index 1. The scheme consists of finding an explicit expression for the integral terms of the equations associated with the Jacobi collocation method. A posteriori error estimation of the method in the weighted -norm was obtained. With the availability of this methodology, it will now be possible to investigate the approximate solution of other classes of IAEs systems. Although our convergence theory does not cover the nonlinear case, it contains some complications and restrictions for establishing a convergent result similar to Theorem 3.1 which will be the subject of our future work.

References

Brunner H: Collocation Methods for Volterra Integral and Related Functional Equations. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 2004.

Hairer E, Wanner G: Solving Ordinary Differential Equations II. Stiff and Differential-Algebraic Problems. Springer, New York; 1996.

Kauthen JP: The numerical solution of integral-algebraic equations of index 1 by polynomial spline collocation methods. Math. Comput. 2000, 236: 1503–1514.

Hadizadeh M, Ghoreishi F, Pishbin S: Jacobi spectral solution for integral-algebraic equations of index-2. Appl. Numer. Math. 2011, 61: 131–148. 10.1016/j.apnum.2010.08.009

Cannon JR: The One Dimensional Heat Equation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 1984.

Gomilko AM: A Dirichlet problem for the biharmonic equation in a semi-infinite strip. J. Eng. Math. 2003, 46: 253–268. 10.1023/A:1025065714786

Kafarov VV, Mayorga B, Dallos C: Mathematical method for analysis of dynamic processes in chemical reactors. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1999, 54: 4669–4678. 10.1016/S0009-2509(99)00277-8

Zenchuk AI: Combination of inverse spectral transform method and method of characteristics: deformed Pohlmeyer equation. J. Nonlinear Math. Phys. 2008, 15: 437–448. 10.2991/jnmp.2008.15.s3.42

Chistyakov VF: On singular systems of ordinary differential equations and their analogues. In Lyapunov Functions and Their Applications. Nauka, Novosibirsk; 1986:231–240. (Russian)

Gear CW: Differential-algebraic equations, indices, and integral-algebraic equations. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1990, 27: 1527–1534. 10.1137/0727089

Bulatov, MV, Chistyakov, VF: The properties of differential-algebraic systems and their integral analogs. Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Memorial University of Newfoundlande (1997)

Bulatov MV, Chistyakov VF: Numerical methods of investigation and solution for integral algebraic equations. Sci-CADE09 2009, 25–29.

Bulatov MV: Regularization of singular system of Volterra integral equations. Comput. Math. Math. Phys. 2002, 42: 315–320.

Pishbin S, Ghoreishi F, Hadizadeh M: A posteriori error estimation for the Legendre collocation method applied to integral-algebraic Volterra equations. Electron. Trans. Numer. Anal. 2011, 38: 327–346.

Canuto C, Hussaini MY, Quarteroni A, Zang TA: Spectral Methods: Fundamentals in Single Domains. Springer, New York; 2006.

Hesthaven JS, Gottlieb S, Gottlieb D: Spectral Methods for Time-Dependent Problems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 2007.

Qu CK, Wong R: Szego’s conjecture on Lebesgue constants for Legendre series. Pac. J. Math. 1988, 135: 157–188. 10.2140/pjm.1988.135.157

Guo B, Wang L: Jacobi interpolation approximations and their applications to singular differential equations. Adv. Comput. Math. 2001, 14: 227–276. 10.1023/A:1016681018268

Shen J, Tang T: Spectral and High-Order Methods with Applications. Science Press, Beijing; 2006.

Tang T, Xu X, Cheng J: On spectral methods for Volterra integral equations and the convergence analysis. J. Comput. Math. 2008, 26: 825–837.

Chen Y, Tang T: Convergence analysis of the Jacobi spectral collocation methods for Volterra integral equations with a weakly singular kernel. Math. Comput. 2010, 79: 147–167. 10.1090/S0025-5718-09-02269-8

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11101109, 11271102), the Natural Science Foundation of Hei-long-jiang Province of China (A201107) and SRF for ROCS, SEM. The authors would like to acknowledge two anonymous referees for their careful reading of the manuscript and constructive comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally to the writing of this paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13660-015-0700-x.

This article has been retracted by Professor Ravi P Agarwal, Editor-in-Chief of Journal of Inequalities and Applications. Following publication of this article, it was brought to the attention of the editorial and publishing staff that this article has a substantial overlap with two articles by Hadizadeh, Ghoreishi and Pishbin published in 2011 in Applied Numerical Mathematics and in Electronic Transactions on Numerical Analysis.

This is a violation of publication ethics which, in accordance with the Committee on Publication Ethics guidelines, warrants a retraction of the article and a notice to this effect to be published in the journal.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, J., Wang, S. Retracted Article: Jacobi spectral solution for integral algebraic equations of index 1. J Inequal Appl 2014, 156 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1029-242X-2014-156

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1029-242X-2014-156