Abstract

Using a qualitative approach, this study sought to identify the factors that influence the psychological well-being or frustration of refugees to Uganda (mainly from South Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo [DRC], Rwanda and other nearby countries) and Ugandan nationals (as host community). Data were collected through nine focus group discussions with 54 participants. The interview guide asked questions about issues that frustrated or encouraged their psychological well-being and the ways they would describe their current psychological well-being. After conducting thematic analysis, 10 themes emerged that contribute to refugee and host community psychological well-being or frustration: food availability, family separation and death, good security in the refugee camp, provision of health services, access to free education, the role of mental health and psychosocial support, unfavourable farmland, availability of employment and income-generating activities, collaboration and peer support, and delayed resettlement within or outside Uganda. Based on participant responses, several recommendations emerge to guide community-based psychological interventions, which may increase the psychological well-being of refugees and host community members. Conclusions show the negative and positive factors that contribute to the psychological well-being or frustration of both refugees and Ugandans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Forced migration has increased worldwide, resulting in detrimental consequences for physical and mental health. In Africa, the major reasons for forced migration are war and poverty. Many refugees are hosted in special settlements, often with living conditions that are insufficient in many regards. This study aimed to examine factors that contribute to the psychological well-being (PWB) or frustration of refugees in a refugee settlement in Uganda (Rhino Camp) and people from the surrounding host community (Ugandan nationals). The Rhino Camp refugee settlement is located in northwestern Uganda, in Arua District, and is divided into the Madi-Okollo and Terego districts. Refugees were first settled in Rhino Camp when it opened in 1980 due to the civil war in South Sudan. The refugee settlement currently hosts 8.5 percent of refugees in Uganda, more than 120,000 refugees [1]. The majority of the refugees in this settlement are from South Sudan, with others from Rwanda, the DRC, Burundi, and Eritrea. Rhino Camp is comprised of seven zones (Ofua, Omugo, Ocea, Eden, Tika, Odobu and Siripi). Although each zone currently has infrastructure, such as schools and health centres, it is apparent that the available services are quite limited relative to the demand for services. Even with such complicating and complex factors, as well as the significant attention paid to the refugee crisis globally, little is known about the well-being of refugees in Rhino Camp. This study tried to address this gap and to ask initial questions concerning the factors that contribute positively or negatively to refugee and host-community well-being, as well as the ways refugees cope with the misery they may experience.

Furthermore, as refugees encounter the host community, members of the host community may also experience positive and negative well-being. For some, frustration from learning about the refugees’ trauma through hearing their stories numerous times has a negative effect on the host community [2]. At the same time, in Uganda, hosting refugees is sometimes perceived as a privilege [3]. Therefore, living in close vicinity to Rhino Camp may have both positive and negative consequences for the host community. Research on host-community psychological well-being is insufficient, and little is known from previous studies.

Perhaps most importantly, the study aimed to provide suggestions for interventions to increase the subjective well-being of refugees and host community members. Because it is very likely that such interventions would have to be tailored to these two target groups, the study was conducted utilizing a qualitative approach to identify factors contributing to the subjective well-being of each: the refugees in Rhino Camp and the members of the surrounding host community. A qualitative approach was chosen for this study because previous studies have been conducted effectively using the same approach with refugees outside Africa. The current study aims to fill this gap and, ultimately, to provide the first recommendations for specific interventions to improve the psychological well-being of the two target groups. Findings may be relevant to and could inform a needs assessment survey of a targeted population, which would be required before any intervention [4].

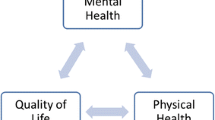

The theoretical framework applied was basic psychological need theory, a subtheory of Ryan and Deci’s [5] self-determination theory, stating that although human motivations are diverse and manifold, the entirety of psychological needs can still be broken down into three basic categories of need: relatedness, competence, and autonomy. Relatedness, competence, and autonomy are vital to the well-being of people across cultural and ecological contexts. These needs are defined as the psychological nutrients that are at the basis of motivational processes and well-being for all human beings. Autonomy concentrates on one’s ability to have a choice and will, being a causal agent, and knowing how to control oneself. The same study affirms that this does not mean being independent but rather having a sense of free will in doing any activity from one’s interests and values. A need for competence refers to one’s familiarity and experience with the environment in which one lives. It also refers to the ways individuals deal with the outcome of any activity they have engaged in and how they associate with the people with whom they live. Relatedness looks at the ways individuals interact and relate freely with one another, feel connected with people around them, and the care one extends to a colleague in as far as daily activities and actions are concerned [5].

Previous studies that relate to my study conducted in Africa (e.g., Horn’s [6] study set in the Kakuma refugee settlement in Kenya) have focused on the emotional and PWB of refugees. Concerns such as overstaying in refugee settlements with no hope of resettlement, physical abuse, and unsupportive family, among others, were found to affect their personal well-being negatively. Other studies have focused on exploring posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and other mental illnesses, as well as the design of interventions [7]. Studies have focused on aspects such as refugee integration and globalization Wamara and colleagues [8]. Refuge policies have also been another area of interest, and this research has led to significant policy revisions regarding refugee management [9]. Studies related to this topic include work by Balyejussa [10], who also researched the well-being of refugees from Somalia who are based in Kampala City. Yet, none of these previous studies looked at basic psychological needs satisfaction as a predictor of PWB. In addition, none applied a comparative approach by including both refugees and host community members. Finally, the current study is exceptional in assessing well-being among refugees who are based in a remote area of Rhino Camp and come from various nationalities, including South Sudan, DRC, Rwanda, Burundi, and Eritrea.

1 Method

1.1 Introduction

Qualitative interview data were initially collected through focus group discussions (FGDs) to understand the factors that contribute to the PWB or frustration of both refugees and the host community. The rationale for having a sequential design was to allow the researcher and the respondents to understand the factors that contribute to their PWB, which may differ from person to person and from group to group. The qualitative interview guide had the following questions: what frustrates or encourages your PWB (subjective feelings of happiness, satisfaction, or dissatisfaction with life)? How would you describe your current PWB? Are there things that you have experienced as frustrations of your PWB (subjective feelings of happiness or dissatisfaction with life)?

1.2 Setting

The study took place in the Rhino camp refugee settlement in Arua District. The refugee settlement is more than 72 km away from Arua City and approximately 449 km from the capital city, Kampala. Participants were recruited from the seven zones that make up Rhino Camp (Omugo, Ofua, Tika, Eden, Ocea, Odobu, and Siripi) and the host community neighbouring the refugee settlement. Fully registered refugees and Ugandan nationals were recruited from these locations for the study. To promote safety, security, and confidentiality, FGDs were conducted in quiet and private tents and, in some cases in classroom blocks for the youths. For the host community, the FGDs took place in homes, compounds, and for Arua town, outside the dwelling.

1.3 Participants

To ensure all groups were well represented, the study involved refugees with five focus groups and the host community had four focus groups; each focus group was comprised of six people, totalling 54 participants. Among the 54 participants were 27 females and 27 males; 17 participants were aged 18–24 years, 29 were between 25 and 40 years old, and eight participants were 41–58 years old. Only eight participants were employed, 12 were in school at secondary level, and two had finished secondary school. The refugees in Rhino Camp represented various ethnic backgrounds and came from different nationalities (Southern Sudanese, Burundians, Congolese, Rwandans, and others). The host community participants included only Ugandans, both adults and youths.

1.4 Procedure and ethical considerations

The Bremen International Graduate Institute of Social Sciences and Uganda Christian University’s research ethics committees approved this study. In addition, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology and the Office of the Prime Minister’s Department of Refugees in Uganda, as representatives of the Ugandan government, authorized the study as well.

For this study, local research assistants or interpreters were recruited, and they were trained on relevant aspects to consider, as well as on the ethical guidelines that included but were not limited to confidentiality and empathy. Before they could begin the interpretation work, during which I relied on them for translation, key terms were translated into local languages and researcher, assistant, and participant roles were explained for the entire process of data collection. Written consent was obtained from all the participants who took part in the study, and the respondents had the opportunity to understand the consent form that was interpreted and translated into local languages represented in each focus group. Only participants aged 18 years and older took part in this study. To ensure confidentiality, no identifying information such as the participants’ names was recorded; instead, initials and signatures were used. During the FGDs, a field tent was used to promote the confidentiality of the participants. Because weather conditions can be intense, the tent also shielded participants from the harsh sunshine and eventual rain during the discussions. Each of the participants was compensated with UGX 28,000 ($0.78) to cater for meals and refreshments as well as transportation expenses. The rationale for providing the stipend was to ensure that the long return-trip distances were sufficiently supported; some had to cover more than 20 km one way within the bounds of the camp. Respondents were informed that the compensation did not mean that they had to provide information they do not have, but rather it was to cater for the expenses and time spent, as explained above.

The members of Uganda Christian University’s research ethics committee visited Rhino Camp to follow up with ethical compliance. They interacted with several participants and confirmed that all procedures were followed and participants’ welfare was assured. The committee has a mandate to conduct such a review, and the participants were aware of the review as explained in the consent form.

1.5 Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used according to procedures outlined by Braun and Clarke [11] to understand participants’ perspectives in response to the research question. Data processing and analysis began by verbatim transcription of qualitative data, followed by initial coding, and then coding to identify similar or related codes and ideas that were then grouped. Finally, themes from the data were created and discussed with the interpreters who helped to ensure consistency. The narrative was prepared by addressing each theme and including participants’ quotes verbatim to support themes.

2 Results

The focus groups from both the refugee settlement and host community reported on several factors that contribute to their PWB or frustration. The results present the entire focus of the study outcome because the study sought to understand which factors influence the personal well-being or frustration of refugees and host society members. The factors that were frequently discussed are presented below. Each theme is supported and has additional context from the literature, and in the following, each theme will be further connected to the literature on basic psychological needs satisfaction.

2.1 Availability of food

In all FGDs, food was the main factor that contributed significantly to participants’ PWB or frustration. For example, refugees reported feeling happy when food is always available, but they reported frustration when food is finished before the next distribution, leaving them with nothing to eat. For those with children, this was even more problematic. In the host community, a food concern was never presented. The host community appreciated the arrival of refugees whom they reported served as a market for their garden produce. Although food is categorized as a physical basic need, the issue of having limited influence on decisions about food can be related to the need for autonomy because major decisions are made by World Food Program (WFP). According to one participant, food reduction is a problem. “Some people are sleeping hungry. The little food given you cannot last the two months. It has really stressed people much” (Rhino Camp refugee, Omugo Zone, 27-year-old female from Southern Sudan).

Another participant said,

I also want to add, food was reduced and the advice they give to the refugees is that they should be tilling their land. It has now become a challenge. Some of the refugees, most of them, are finding their way back to South Sudan in the country. The place is not yet okay, war is still there. Unfortunately, others go and they are shot dead. (Rhino Camp refugee, Ofua Zone, 34-year-old male from Southern Sudan).

Yet another said,

I think when food is scarce, food at home is very scarce and that shortage makes me feel unhappy. Because of that shortage of food, sometimes my children cry for food, but I could not even provide for them. I myself, I cannot even sustain myself (Rhino Camp refugee, Ocea Zone, 44-year-old male from Sudan).

2.2 Family separation and deaths

Across the majority of focus groups from the refugee settlements, it emerged that separation from their family members negatively affected their PWB on a daily basis. This was coupled with the inability to attend burial ceremonies when a beloved one died in a location far from the camp. Refugee participants stressed that they cannot travel to their respective countries due to fear for their lives, and instead they live with their grief in the refugee camp. Some were unhappy with burying deceased loved ones in the camp, noting that when they may eventually be able to return to their countries, they will leave their past loved ones buried in a foreign land. Frustration resulting from a lack of relatedness to family and burial practices is a prominent theme in this discussion of basic psychological needs satisfaction. “You know, at this point, when we are in the settlement, some other things were not in place as usual, as we had them before,” said one refugee. “And since we came here, you know, we lost a lot of things, lost families” (Rhino Camp refugee, Tika Zone, 38-year-old male from Southern Sudan). Another said, “One of the things that made me unhappy is sickness; also, if you lose a loved one, those are the things which make them unhappy” (Rhino Camp refugee, Ofua Zone, 22-year-old female from Southern Sudan). Another said, “Losing my family, my friends, people who died when I was here and not able to bury them, things like those cause frustration” (Rhino Camp refugee, 19-year-old female from Rwanda).

2.3 Good security in the refugee camp

Security emerged as a positive factor for all the refugees and for Ugandans in the host community. In contrast to their country of origin, the environment of the refugee camp does not typically include exposure to gunshots or rebel attacks, and thus refugees reported the absence of such worries contributed to feeling happy and comfortable. They reported that this contributes positively to their PWB. The focus group participants viewed the Rhino Camp as a peaceful environment compared to their previous countries where they experienced daily attacks by rebels. Participants reported that children born in the Rhino Camp have not heard of or experienced war and that they wanted to spare them of this experience. Credit was given to the Ugandan government for ensuring good and reliable security beginning with border entry and in the refugee camp. Security, as a theme of PWB, relates to the need for competence. In this case, competence is needed at a societal and governmental level to promote safety. One refugee said,

To me, what makes me happy in this settlement, I am just free, not as I used to be in South Sudan; you don't hear the sounds of bombs or people shooting at other people, so I feel that I'm just safe here in the settlement” (Rhino Camp refugee, Omugo Zone, 45-year-old female from Southern Sudan).

Another said,

I think I have an idea, what I've seen, what makes me happy is my security, because here in the settlement, I cannot see armed men carrying guns for killing people. But the arms they carry are just for protection, for security, and I can also see people carrying guns in the food distribution centre, just for protecting my food from someone going to take it from me, and I cannot see someone dying because of insecurity. So, that’s what makes me happy in this settlement (Rhino Camp refugee, Odobu Zone, 35-yearold female from Southern Sudan).

In addition, a refugee said,

When I wake up from here, of course I feel glad because I'm alive and I am safe, and I have to be first of all happy for life. In summary, I can say I feel secure because I wake up and I'm safe. Nothing has happened to me here, at least I have some reason to be happy (Rhino Camp refugee, 20-year-old male from Southern Sudan).

2.4 Health services

Refugee participants described free access to medical health facilities as a relief. The focus groups from the refugee camp mentioned health care as another basic need that has been addressed living in the camp. Addressing health concerns can also be attributed to the need for competence. To some extent, refugee participants reported feeling frustrated in circumstances when certain drugs were not at health centres and they were advised that they had either to wait or to buy from clinics, which are not within their reach.

Let me talk on behalf of health. As refugees, when we were brought here, we saw that they provided us with health facilities where there are services of treatment. When you’re feeling sick, you come to the facility. They test you when you have malaria. They give you drugs instead of you using the small amount of money from causal work and going to the clinic and buying drugs, but here, since there is a free facility, you just come freely. They test for malaria, they give you drugs, you go home, and you become fine. I am very happy myself because I've come as a refugee and I've seen that in this facility people are not dying because of malaria and other diseases. If at all you are sick, you just come to the facility straight away. Then you are worked on. They give you drugs then you become fine. (Rhino Camp refugee, Omugo Zone, 33-year-old female from DRC)

Another refugee said,

They might tell me these drugs are not there. You go home, maybe come and check for these drugs after some days or one week or two weeks, but if you come back and find they're not there and that they're out of stock, then that's another challenge. Well, we also see that it is also challenging and sometimes it is risky. You might end up dying because you do not have the direct drug for your treatment (Rhino Camp refugee, Ocea Zone, 24-year-old female from Southern Sudan).

2.5 Education

FGDs involving the refugee and host community groups indicated the need for quality education at all levels was an important benefit for both groups’ children on the side of parents. However, parents in the refugee camps became frustrated when asked to pay school fees for children in secondary schools because they have no source of income. The youths who took part in this study said continuing with education made their future seem bright, yet this was not the case with youth refugees, who noted that they see no future ahead because they cannot advance their level of education to university. Higher education would provide an opportunity to work towards the future and would positively affect their PWB. The host community praised the support and empowerment of girls, who are afforded free education at the primary level from Universal Primary Education (provided by the Ugandan government) and who overall show outcomes such as reduced school dropouts, fewer early marriages, and fewer teenage pregnancies. Prior to Universal Primary Education’s introduction, these outcomes for girls were higher. Registration for the education benefit is complicated by the demanding scholarship criteria that make it difficult for many refugee students to receive free tertiary sponsorship; as such, refugee participants reported frustration related to competence in this area of basic psychological needs satisfaction:

Most, at first, our children would go to school and at that moment, they learn for free, but to some extent, what I have seen as a challenge is that we have been told to pay money mostly for secondary school, so it is a challenge for some parents. It has made children go into the street to be exposed to drug abuse, and this causes rampant cases of criminality in the community, teenage pregnancies. This is because they are unable to afford what they are supposed to do, because of the conditions that we are facing here (Rhino Camp refugee, 21-year-old male from Burundi).

Another refugee said,

In addition to what frustrated me much since I came into this settlement, like most, when the scholarship or sponsorship comes, the qualification for it will not match the youths who we have on the ground. That’s why it limits the youths from continuing with an education. That is the main thing that affects us too much! (Rhino Camp refugee, 21-year-old male from Burundi).

Another refugee added,

Being in school makes me happy. It also prevents one from being spoilt and from falling into an early marriage because one thinks so much about it when they are not in school. Even the girls cannot have a teenage pregnancy (19-year-old Ugandan male student from the host community, Arua District).

A refugee parent at Rhino Camp said in an FGD, “My children cannot go to school; this is so frustrating for me.”

2.6 The role of psychosocial support

Refugees appreciated the initial and continuous support offered to them in the form of psychosocial support. In some FGDs, they said this helped them to avoid delaying treatment for the traumatic and stressful events that they experienced. Others looked at psychosocial support as an ongoing activity to which they always resort whenever feeling overwhelmed by the difficult living conditions in the refugee camp. However, stigma was highlighted as a concern among those who seek psychosocial support, because they are termed as mentally ill. The concern of being stigmatized has hindered many from utilizing the service. Although the services are offered by international nongovernmental organizations and they are seen as a factor reflecting competence in support of basic psychological needs, the stigma can outweigh the inclination to take advantage of the services provided. A female refugee said, “When I came here to the camp, the first thing I received that helped me was the psychosocial support. It helped me much” (Rhino Camp refugee, Ofua Zone, 29-year-old from South Sudan, female). Another refugee said, “Concerning psychosocial support, I know the well-being of the person requires counselling. Me, I know I am now okay. When I came, I had stress that made me unhappy in the camp” (Rhino Camp refugee, Eden Zone, 48-year-old male from South Sudan).

Refugees became frustrated when they were unable to access psychosocial support services in their respective places at any time they were needed. They have always relied on the mental health and psychosocial service providers at all times for the management of mental illnesses such as acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and separation anxiety disorder, among others. One refugee said, “Nowadays, unfortunately, the psychosocial support services are meagre. People are traumatized” (Rhino Camp refugee, Tika Zone, 32-year-old female from South Sudan). Another refugee said,

She first of all appreciates that when she was coming up to the border side, she had a mental illness. She was happy. They told her if she reached at Omugo. She will come up at the health centre. She will get somebody called Juma who works with TPO on mental health issues. She will be helped. Actually, she came and she found your mental assistance helped her, but also, what makes her unhappy sometimes is that the TPO was not always there in the settlement. That is what made her unhappy (FGD, Rhino Camp refugee, Omugo Zone, 28-year-old from South Sudan).

2.7 Unfavourable farmland

The FGDs from the refugee camp reported frustration due to poor land topography and the dryness of the area, neither of which is favourable for crop growing. Having no opportunity to cultivate food and supplement aid they are provided by the WFP, many refugees are vulnerable because of their single dependency on food aid. Regardless, many attempt to cultivate the land, just like refugees in other camps. Frustrations related to food and farming insecurity cannot be separated from the basic psychological need for autonomy, whereby refugees have limited choice in sustaining access to a diverse diet, but the host community has full control of options to choose from and access to various sources of food. “We are trying to set up farms, but the pattern of the rain here cannot really allow us to produce what we want to produce,” said a 26-year-old male refugee from Rhino Camp, Ofua Zone. “It has really stressed me much.”

Another refugee said, “The topography of the place is not okay, where you can start a livelihood project that can sustain your life; that is the main challenge” (31-year-old female Rhino Camp refugee, Omugo Zone, from South Sudan). Another added, “We are in this place where one is not able to cultivate, and it’s actually making us just remain poor from time to time, so that is also why I am not happy being here” (Rhino Camp refugee, Ofua Zone, 28-year-old male from South Sudan).

In addition, they talked about difficulties with host communities pertaining to sharing land or farming resources and products. Stories were shared describing a desire to use additional land to grow vegetables and other fast-growing crops but they are prohibited or discouraged. Additionally, in some cases, the host community is accused of harvesting the refugees’ food without permission, which leaves the refugees feeling disgruntled and frustrated:

On the native side, they would be friendly with the nationals, but sometimes we have issues of land, and then after cultivating, some of them turn negative at harvesting. You find your things are harvested, which is causing most of the problems for people” (Rhino Camp refugee, Omugo Zone, 43-year-old male from South Sudan).

2.8 Employment and income-generating activities

Participants in FGDs in both settings were happy when engaged in income-generating activities or employment. Income and productivity created more avenues for self-reliance and thus sufficient family support, and in turn reducing aspects of dependency upon nongovernmental organizations. Yet, most refugees reported being unable to obtain jobs that correspond with their educational qualifications and they were unhappy with being given volunteer jobs or lower-paying jobs. This was not the case with focus groups in the host community, who viewed the presence of the camp as a means of reliable job opportunities for the host community. When individuals strive for financial freedom in the form of employment and involvement in income-generating activities, it reflects a fulfilled basic psychological need of both feeling competent and autonomous (i.e. able to support oneself and one’s family, as well as free from the dependency upon nongovernmental organization resources). One refugee said,

I feel okay because I've gained stability. By the time I arrived, I was just stranded. But later, when I found a job, I could manage the children with whom I came, so, I was like a father, and I was like a mother behind the children” (Rhino Camp refugee, Omugo Zone, 29-year-old male from South Sudan).

Another refugee said, “I can also add on what makes me unhappy. In most cases, we lack opportunities, things like employment opportunities, which are very scarce in the settlement” (Rhino Camp refugee, 33-year-old female from DRC). A 28-year-old male refugee said,

If there is no work to do, it makes you feel stressed in the community, even if there is electricity. For you to benefit, you have to have a job, to have something to do so that you can get a little money to enjoy whatever you want to do. That’s where the happiness will come. You have some petty jobs to do like Boda Boda riding, then one can be happy” (Rhino Camp refugee, Ofua Zone, from South Sudan).

2.9 Collaboration and peer support

In almost all youth FGDs, a common theme was that they enjoy interacting with peers from other countries, especially in the case of refugee youths regarding host community youths. Both Ugandan and refugee youths reported positive moments when they experienced peaceful interactions between each other. It was later pointed out that aspects such as sports, sharing of cultural practices, sharing experiences, and, in one case, dealing with painful or distressing situations are some of the key things the youths enjoyed sharing with one another. These types of interactions have promoted peaceful coexistence among youths in both settings, and they are eager to learn from each other and offer peer support. Ugandan youths hope to be treated well if they happen to go to Sudan, and thus they treated their peers in good fashion while in the refugee camp. Collaboration and peer support is a clear example of the need for relatedness and applies to both refugees and the host community, with examples provided by each group:

Another thing I can say that is positive about this place is that people come expecting to meet others, especially here, we are three nationalities. Even though they have another nationality, you find that you meet new people and share ideas in common with them, where they come from, and learn about their culture. That is one advantage.” (FGD protection home).

Another participant said,

Having a good friend, like we have neighbours around us refugees, specifically a good friend from them, you can at least share some things that you are not even aware of, which will help. You never know, you may reach Sudan, which will guide you to stay confident in public like that, like how to stay with people in the communities, you know. Each country has its own rules and the way to stay with some cultures is different. Like here being a Lugbara by tribe, we have our behaviours. But when you reach that side, people also have their different ways of behaving. You find it easier to relate (20-year-old Ugandan male from host community).

Youths also say it is easier for them to mobilize towards advocating for peace; they view themselves as agents of peace in their respective countries, where tribal disputes have resulted in war. Good relations among them have made it easier for them to talk to each other as they create greater awareness and advocate for peace. Both groups of youths hope they can practice peace in the same way when they return to their respective countries, in the event repatriation occurs.

So, I am like, “What should I do by the way?” My own country is misbehaving. They certainly misunderstand themselves; they don’t want to talk about things in common. So, with all that, I met one of the peacemakers. They call themselves “peacemakers.” We formed a group, they were counselling people how to have at least that . . . that heart where you can be patient any time and the country can be fine. They told me today the country might not be fine, but you never know, tomorrow the country will be okay. So, that word has encouraged me, I am at least happy. So I hope that tomorrow, the country will announce that there's already peace, people have to go back” (Rhino Camp refugee, Ofua Zone, 23-year-old male from South Sudan).

2.10 Delayed resettlement

Specific focus group discussions pointed out the idea of delayed resettlement, characterized by concerns of staying in one place for longer than was initially anticipated. Many refugees reported that they had hoped to stay for less time in Rhino Camp before being resettled to other parts of the country or even outside Uganda. They felt fed up with staying in one place and held a primary interest in leaving Rhino Camp. Delayed resettlement was one aspect causing distress to those who did not view Rhino Camp as a second safe and happy home and who were in favour of living outside the camp. One participant said,

I personally am living with my parents. Most of what makes me sad is the time I had some expectation but cannot get in this place. One expectation is an issue related to…. The first was security, and the second was resettlement. But the expectation which I had was maybe too short a time as they promised that maybe after six months to one year the issue would be solved. But there are people who have stayed here for five years now, going on six years. These have affected me in many ways. It has affected me psychologically as I’m thinking about the future. Now I am 26 years old (Rhino Camp refugee, 26-year-old male from Burundi).

3 Discussion

Before the discussion, it should be noted that the objective of this study was to identify what factors contribute to the PWB of refugees and Ugandans. From the FGDs, themes were identified and later merged into larger themes which were related to BPNT. In this section, I discuss the current findings as well as those from previous investigations.

Food security remains a key concern among refugees in Rhino Camp as they mainly rely on aid from the WFP. There is no doubt that any delay or reduction in food rations will place them in a vulnerable situation because they have no other access to food. The larger family sizes of respective refugee homes further exacerbates this situation, and the same was observed in schools due to the increased number of learners [4]. Surviving on little food may result in having to skip some meals in a day or even going without food for a day. Cases of food theft have also increased inside and outside refugee settlements, as found in a recent study in Kyaka II refugee settlement. This is also seen as a risk factor for conflicts between refugees and Ugandan nationals, as reported by the UNHCR [12]. The UNHCR has always prioritized this aspect of food distribution to refugees through implementing partners such as AFI and World Vision. This food distribution has enabled refugees to meet their immediate nutritional needs [13]. However, the question remains, is the food supply sufficient for refugees to survive until the next distribution? Moreover, are the refugees engaged in discussions before food rations are increased or reduced? This appears to be one of the key concerns for the refugees, for whom the distributors have already made decisions. The refugees only have to obey. It should be noted that in some cases even those who received cash for food complained that it was not sufficient, according to the results of the assessment report by [12]. This report found that the Ugandan Shs 31,000 (0.86$) given to individuals was inadequate to sustain them for an entire month.

In the FGDs, students and their parents raised concerns about access to education. Specifically, youth feel more hopeful when they are receiving education or acquiring specific skills. Education is a key tool with which they can start to live and survive when they return to their respective countries. Schools are constructed in the refugee settlement, but this study documented that most of them concentrate on lower grades with very few secondary or technical schools. As a result, some youth miss out on school, joining peer groups that sometimes have negative consequences. Very few refugee students manage to go to university with scholarships, and this leaves the majority with no continuation after secondary school. This not only limits career opportunities for learners but also their PWB. Poor performance also affects PWB [6]. The provision of education to refugees remains a major service from the UNHCR through its implementing partners. Several schools have been established in various refugee settings, and this has not only benefited individual refugees but also the host community where learners are not charged fees to access these free services [14]. In most cases, the long distances that learners must cover to reach school is a primary concern. Schools tend to be far from home, and sometimes there is only one secondary school in an entire sub-county. Thus, there is concern about poor educational infrastructure with increased demand in refugee-hosting communities. Sometimes the number of students in refugees’ schools is high compared to the target number or expected number in a particular class. Education remains a key concern in all refugee settlements, as other refugee service providers have researched with the aim of improving service delivery [4].

Health services in refugee settlements are in place and can easily be accessed. Implementing partners also offer mobile clinics to reach out to refugees and host community areas far from health centres. These clinics provide timely detection and treatment of illnesses. The provision of mobile clinics also supports persons with special needs (PSN), who are sometimes unable to walk long distances. Making these services readily available and free of charge has built more trust in health-implementing partners, and more host community members enter refugee camps to set up health centres. This act has also created good relations between refugees and their host communities, who see the arrival of refugees as a great benefit. Some refugees have found jobs working in the same health centres as medics or language interpreters or in other casual jobs offered to both refugees and Ugandan nationals, enabling them to earn a living in addition to health improvement. These health centres are often overwhelmed with patients whose numbers outweigh the staff or even the facilities available. This is in agreement with a study by Amegovu [15], who found that the number of refugees seeking health services often overwhelms the service providers in the Nakivale Refugee Settlement in Uganda. In addition, refugees are more likely to miss out on timely referrals to regional hospitals, which are often more than 40 km away from a refugee settlement. This is also in agreement with a study that found that restricted access to health care negatively affects the PWB of refugees [16]. In addition, transport can be unreliable due to the high demand for the few hospital ambulances available.

In this study I also found from the respondents that amidst the hard living conditions in the refugee camp as well as in the host community, there were key coping strategies in which they would later engage. These included but were not limited to setting up home gardens to grow simple vegetables. The host community benefited through the sale of their food to the refugees. In addition, refugees offered to counsel each other in times of sorrow. Some opted for marriage to find companionship with someone they could always talk to. Some refugee groups started village savings and loan associations to support themselves financially. Refugee youth initiated peace-talk clubs and engaged the host community through sports activities as a means of creating peaceful coexistence. Also key among coping strategies, respondents sought psychosocial support from agencies in the camp or attended prayer services. The aspect of hoping for better times to come amidst tough times—buffering against adversity—was clearly visible in this study. Both refugees and host community members expressed hope that things would turn out for the best. They would also point out the agencies that would encourage them to remain hopeful and stay united. All of these accounted for why large numbers of refugees acknowledged that they were happy. Similarly, this applies to the host community.

It was evident from the FGDs that refugees considered themselves to be vulnerable and that they needed more attention ranging from non-food items to food items, education to security, and psychosocial support. They considered these things to have a great impact on their PWB. This was contrary to the host community, who reported limited factors contributing to their PWB; however, they demanded better delivery of services as they provided land to the refugees. Both the hosts and refugees were mostly concerned about unemployment, education for the youth, and peaceful coexistence. Otherwise, the two groups had different needs and coping strategies. This can also imply that any mechanism providing help to the two groups will need to approach each group in a unique way. For example, the host community does not need an intervention related to food distribution or decisions related to food increase or reduction, but they rather need guidance regarding which foods to grow as the majority grow tobacco, sim-sim or cassava, which require a long time to grow. Some, such as tobacco, can only be sold, not eaten, thus contributing to hunger in the region. This may be why some host community members have registered themselves as refugees, in order to get food.

The inability to conduct home gardening and farming has contributed to a shortage in food supplementary supply among refugees in the Rhino Camp refugee settlement. A study conducted by Njenga et al. [17] also observed the same problem and advocated irrigation and the use of compost and biochar for soil improvement. As they had no other assured sources for accessing food, refugees felt frustrated when they delayed or failed to get food on time and in desired quantities. This study also found that the refugees were not concerned about the variety of food given to them but rather the quantity they received per month. In refugee camps where land is fertile with a favourable climate, refugees have fully participated in serious commercial farming, sold food to WFP, and then kept the rest for home consumption. This has left them happy with earning and with a peace of mind that resulted in balanced PWB. It is also impossible for all refugees to be hosted in fertile places within the country. The Rhino Camp is different from other settlements as it is located in the West Nile region, which is mostly dry and cannot be compared to Kiryandogo and Kyangwali refugee settlements in the western region. These settlements are more fertile with good rain patterns that favour farming among the refugees. Some have also gone out of the camp to rent land for farming. This has greatly improved their engagement in income-generating activities and led to good relations with the host community and most importantly reduced dependence on food aid.

The provision of psychosocial support by refugees has seen more positive results between them and their host communities. This has had a positive impact on their PWB. Whereas the services of psychosocial support are vital, it is still a challenge that not all those who need this service utilize it as much as it is available [18]. In instances where psychosocial support is offered and utilized, few problems are a result of the psychological distress of substantiation as opposed to situations where this service is not offered. According to Williams and Thompson [19], community-based interventions are emphasized where non-specialized individuals are trained to offer psychosocial support to fellow refugees or host community members, as this is more efficient and sustainable due to the high demand for mental health support.

Refugees with the capacity to obtain employment in better positions or even compete for jobs commensurate with their level of education, skills or even work experience often tend to accept low-paying jobs for which they are over-qualified, as observed in this study. This leaves these individuals unsatisfied and earning less than what they could get. This is also in agreement with the findings of Loiacono and Vargas [20] who also add that, on the whole, refugee women were less likely to look for jobs than refugee men were. My study also revealed that some refugees simply become reluctant to work because they have adequate access to food and non-food items (NFIs) in the refugee camp. On the other hand, though some refugees seeking work have neither academic qualifications nor work experience, they demand employment, especially in jobs within the refugee settlement. As recruiting agencies, organizations follow a set of standard procedures that overlook certain refugee applicants, leaving them unhappy and unemployed. Since the policies permit these refugees to work, those who meet the criteria and receive work are grateful for the opportunities to apply their skills and receive a reward in the form of a salary. Uganda has given refugees the freedom to work in the areas next to their refugee camps or in the refugee settlements themselves, permitting refugees to exercise their right to work as long as they meet the job requirements and provided that there are job opportunities. It should also be noted that Ugandans are battling the issue of unemployment; many cases in which refugee applicants receive no job offers are tied to the large number of qualifying applicants competing for the same positions. Ugandan nationals’ greater stability enables them to stay longer at their jobs; some refugees habitually self-relocate from one refugee settlement to the other, which may reduce their chances of being employed before Ugandans.

Besides paid employment, the ongoing empowerment of refugee projects generates income both at the individual and group levels. Several such initiatives have trained refugees in various potentially lucrative skills such as baking, weaving, winemaking and other trades resulting in goods the refugees can prepare and market within the refugee settlement. The refugees have also been trained in financial management skills. All these developments have extended opportunities to the host community as well, due to the government policy that requires all activities conducted within the refugee settlements should be carried out in the host community, refuge to host community share (60% for refugees and 40% for host community). This has promoted the development of host communities alongside that of the refugee community, letting the host community appreciate the refugees’ presence in their respective places. International labour organizations also empower refugees through the use of key aspects of the Ugandan model, permitting refugees to work, utilize land through cultivation, and move freely within the country, and access health services and education. Refugee settlements in Uganda, particularly in the southwest, usually host large markets where refugees sell products harvested from their gardens.

Another positive finding of this study centred on the adept collaboration strategies exhibited by young people who frequently interacted with refugees of different nationalities or ethnic backgrounds in various domains like sports or cultural activities. This study also found that, in the host community, young people related well to the refugees in the refugee camp. Most importantly, refugee youths acknowledged the need to learn new skills (such as a language) and how to offer peer support since most of them rely on each other for support. Peer support, on the other hand, seems to play a key role in helping refugees access support before any other help comes in; these are new and vital milestones that should not be taken for granted since they bring healing to those who need help. In refugee settlements in Uganda where there has been productive collaboration among refugees themselves or even between host communities and refugees, there have been no conflicts, in contrast to environments in which misunderstandings, in most cases tribal, amongst refugees are more common. These incidents have cost some refugees their lives in the West Nile region (Bidi Bidi and Rhino Camp refugee settlements) and in the northern region of the country.

All refugees fleeing their countries hope to find a safe and peaceful environment. However, this study has found that while there were groups of refugees who felt safe and were happy to stay in Rhino Camp (citing good security, alongside other positive aspects), other members in this study indicated through the FGDs that they were to stay in Rhino Camp for a few months but hoped to be resettled in other places within the country or even be taken outside Uganda. To their frustration, months have turned into years: some said they had been in Rhino Camp for six years, with no hope or clear plan for their resettlement in desired locations. Several interactions with the refugees clearly demonstrated that some would be safer if settled away from the refugee camp. This can be ascribed to the promises of resettlement, made by the authorities in charge that provoked refugees’ anxiety as they hoped for their next homes and accepted Rhino Camp only as a transit camp. Globally resettling refugees remains a major challenging task as each country has specific laws and policies towards refugee support and acceptance. Amidst these logistical delays, the UNHCR has always provided the required protection to these refugees who may be at high security risk if not fully protected, something which has provided them some contentment even as they sustain resettlement expectations. Some refugees have countries of preference, which, in most cases, has been seen as a driver of self-relocation; however, this does not apply to all refugees. As to whether some may expect greater economic gain than they do peace remains another concern, as this affects families of refugees where one family member (e.g., the head of the family) may flee and leave the rest of the family behind.

Uganda has received praise for ensuring peace within the country, but even more so for its extension of this peace to neighbouring countries facing insecurity, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan, and Somalia, among others. This is the same support that has been extended to the refugees within Uganda, who are given security upon entry at the border and in the refugee settlement. Through its protection section, UNHCR prioritizes security, because it cannot conduct activities in refugee settlements where there is insecurity. It is notable that in Ugandan refugee camps, refugee commandant heads are very attentive to security, as some refugees are army deserters who must be handled by people who are well-trained in security-related aspects. In some refugee camps, rebel groups have been reunited, requiring the government to ensure full-time security in these settlements. There is no refugee camp in Uganda that one can enter without the permission of security. This has surely given refugees a sense of peace: in the FGDs, they reported that they saw armed security in Uganda as promoting peace, not as threatening attack. Prioritizing security can be associated with good PWB among refugees and in host communities around refugee settlements [21].

Culturally appropriate burials have taken place within the refugee settlements. UNHCR protection partners in Rhino Camp (for instance, IRC) work with refugees who lose their loved ones to ensure that they can bury their deceased family members in a well-arranged and culturally acceptable manner. Though the concern that these people are not buried in Southern Sudan remains, some refugees are content to bury their dead in this way rather than losing them in war, which they say makes it impossible for them to bury them at all. At burial ceremonies, refugees are joined by fellow refugees to send off their deceased loved ones. This has created additional collaboration and emotional support among refugees, not only among those in Rhino Camp, but also among those in other refugee settlements in Uganda and in the East African region. It is also possible that, having stayed in the country for more than 15 years, some refugees call Uganda their home; hence, having appropriate and culturally acceptable burials in certain places continues to provide them a sense of stability in such places by creating ties to the graveyards of their loved ones, which is taken seriously in most African cultures.

The general theoretical framework for the current investigation was basic psychological need theory (BPNT), derived from the self-determination theory of Ryan and Deci [5]. Accordingly, a threefold structure underlies the complexity of human motivation across domains: autonomy, relatedness and competence. The current study’s findings indicated various forms of how BPNT is exemplified by refugees and the host community in aspects of relatedness such as collaboration and peer support, family separation and deaths. There was a great need for and valuing of collaboration and peer support between the two communities (refugees and the host community). This spread further across different ethnic boundaries in the refugee community; refugees viewed collaboration as something able to unite them, on which they hoped to rely for peace building when it is safe to return to their respective countries and they are repatriated back home. Similarly, the issue of family separation and anxiety was more pressing in the refugee community than it was in the host community. This can be attributed to the existing family support in host communities, often absent among refugees. However, in both host and refugee communities, members joined to say goodbye to deceased loved ones, which brought unity to the area.

Furthermore, competence functioned differently in the two communities’ contexts of needing employment, income-generating activities, education and farmland. Education contributed to the PWB of both refugees and Ugandans, however, this was expressed differently. The struggle to attain education or complete tertiary schooling meant little to refugees, as each refugee zone has schools set up. By contrast, the host community was grateful for these schools’ creation, which reduced the long distances Ugandan students had to travel to access the few schools that existed before the refugee camps. Now, the host community reports that many girls have benefited from this access to education services; in the past, girls often entered into early marriages, so this development is good news for the host community.

Income-generating activities, as well as employment, were a uniform concern across the refugee and Ugandan communities. However, Ugandans were open to a wide range of opportunities because they could attain higher positions than the refugees could. In fact, refugees often applied for low-paying jobs significantly below their academic qualifications, something that can be related to their under-evaluation of their own potential.

The final basic psychological need, according to BPNT, is autonomy. This was primarily expressed through refugees’ need for farmland favourable to providing supplementary food, food availability, and their demand that their suggestions be heard on decisions related to food matters, since they were not always consulted in circumstances of deciding on food increases or decreases. However, land brought with it additional concerns, as it had the potential to create disputes or harmony, depending on the way it was handled in each zone. The host community was willing to rent out land to the refugees at a low cost of about 80,000 Ugandan shillings per acre for a whole year. This was welcomed by those who could afford it and opposed by those who were unable to afford it. In general, the host and refugee communities share land at the moment as refugees’ access to the host community is not restricted. All this contributes to PWB in either way. Thus, BPNT proved to be an appropriate framework for clustering the emerging themes into meaningful basic categories.

3.1 Study limitations and future considerations

The majority of the participants in this study were refugees from Southern Sudan. This could have limited opportunities to explore the concerns of refugees who came from other countries such as Somalia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo who mostly reside in Kampala basically the Somali refugees and also majority of Congolese refugees live in western Uganda (in the Kyangwali refugee settlement). Future studies should, therefore, consider engaging these groups. Another limitation was the study’s focus only on participants aged 18 years and above. Since most refugees are women and children, the study may have excluded the opportunity to discern which factors contribute to children’s PWB or frustration. Feedback from these age groups could also guide current and future interventions for children. Therefore, future studies should consider the possibility of including children in the sample.

4 Conclusions

According to the study’s findings, food distribution, security in the camp, family separation or death, and physical healthcare were found to be the major sources of PWB or frustration. Furthermore, provision of mental health and psychosocial support did not draw as much attention as did other services provided to refugees, like WASH, protection, food and others. Therefore, this study recommends emphasizing empowering refugees to grow their own food, strengthening family systems and social support, enhancing the provision of health services by increasing the number of service providers who implement mental health and psychosocial support services, and training refugees and host communities in brief MHPSS interventions such as self-help, which will empower these groups to support themselves in the absence of support staff and to use the same strategies upon returning to their respective countries. These short-term interventions are sustainable and inexpensive to teach.

This study uncovered an interesting aspect of young refugees’ relations, which were strong not only among refugees but also with young people in the host community. This indicates productive co-existence between these communities that aspire to collaborate and work with each other. Therefore, this study recommends boosting youth interaction-related activities to bring them together. These activities include but are not limited to sports activities, inter-school co-curricular activities (such as debates) inviting schools to visit each other for competitions, youth dialogues (which could focus on youth-related concerns like career development or life skills) and sharing ideas amongst themselves, complementing the aspect of relating to each other peacefully.

As many refugees continue to have frustrations due to their delayed resettlement, the lack of concrete information on the progress of that process worsens their anxiety even when they are provided with other services like WASH, protection, and education. The findings point to the need to provide clear and forthright information about the dynamics that underlie resettlement, not only information about general resettlement progress. With such information, refugees will be more prepared for any eventualities (for example, delayed resettlement or even the failure to be resettled). The parties in charge may need to assess the factors that lead to successful resettlement and speed up this process, as some refugees may only feel safe when they are relocated to other, safer places.

The study can conclude that almost all the participating refugees, as well as the majority of the host communities in Uganda, live without employment or any income-generating activity. This has forced some Ugandan nationals to register themselves as refugees so that they can benefit from the free services given to refugees; in other circumstances, some have participated in violent riots near and within the refugees’ settlements while demanding access to free services (such as food, among others) because they offered land to the refugees. This study recommends more activities be set up to empower both communities to provide for themselves rather than relying on aid from organisations. In this case, training in income-generating activities could emphasize, first, teaching beneficiaries how to handle and manage finances, as some lack this skill of financial management, leaving them to recklessly spend their hard-earned money and struggle for money thereafter. Employment, too, can be boosted by encouraging refugees with relevant skills to apply for jobs in those specific areas rather than applying for low-paying jobs while having specialized skills. More skills training and education would benefit those who early in their careers. Access to technical and higher education should extend throughout both communities; though lower-level education (e.g., primary) is widely available, scholarships that match refugees’ standards and encourage learners to stay in school are still necessary, as this study found that not all those of school age in the refugee and host communities went to school when schools were in place. Once these resources are provided and educational opportunities expand, so too might skilled refugees and Ugandans increasingly be in a position to apply learnt skills in earning a living or to apply for relevant jobs and earn money for services they offer. All this will increase the chances of self-reliance and promote competence among refugees and Ugandans.

This study contributes to the literature on the factors contributing to the PWB or frustration of refugees in the Rhino Camp refugee settlement as well as in the host community in the Arua district. The findings can serve to represent potential concern(s) of other refugee settings in Uganda and across the region. The documented findings have implications for the organizations implementing various services in refugee settings, not only in Uganda but also in other refugee settlements. These findings also provide direction for future research on the development of interventions for these populations.

Data availability

The datasets used for the analyses of the current study are not publicly available. However, they can be obtained from the corresponding author.

References

UNHCR. Uganda refugee statistics: October 2020, Bidi Bidi. no. October, p. 2020, 2019, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/72292. Accessed 28 Sep 2022.

Gebrehiwet K, Gebreyesus H, Teweldemedhin M. The social health impact of Eritrean refugees on the host communities: the case of May-ayni refugee camp, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2020;13(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-020-05036-y.

Hellmann JH, et al. Ugandan and British individuals’ views of refugees in their countries: an exploratory mixed-methods comparison. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2556.

Papageorgiou E, Digelidis N, Syrmpas I, Papaioannou A. A needs assessment study on refugees’ inclusion through physical education and sport: are we ready for this challenge? Phys Cult Sport Stud Res. 2021;91(1):21–33. https://doi.org/10.2478/pcssr-2021-0016.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68.

Horn R. A study of the emotional and psychological well-being of refugees in Kakuma refugee camp, Kenya. Int J Migr Heal Soc Care. 2009;5(4):20–32. https://doi.org/10.5042/ijmhsc.2010.0229.

Logie CH, Okumu M, Mwima S, Hakiza R, Chemutai D, Kyambadde P. Contextual factors associated with depression among urban refugees and displaced youth in Kampala, Uganda: findings from a cross-sectional study. Confl Health. 2020;14(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-020-00289-7.

Wamara CK, Muchacha M, Ogwok B, Dudzai C. Refugee integration and globalization: Ugandan and Zimbabwean perspectives. J Hum Rights Soc Work. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-021-00189-7.

Zhou Y-Y, Grossman G, Ge S. Inclusive refugee-hosting in Uganda improves local development and prevents public backlash. Mar 2022. http://www.pdri.upenn.edu/bio/shuning-ge. Accessed 28 Sep 2022.

Balyejjusa MS. The wellbeing of Somali refugees in Kampala: perceived satisfaction of their human needs. J Sci Sustain Dev. 2017;6(1):94. https://doi.org/10.4314/jssd.v6i1.6.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

UNHCR. Uganda: Age, gender and diversity participatory assessment report. 2018. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/71165. Accessed 28 Sep 2022.

UNHCR. Food Security Dashboard. Nov 2020. 2020–2021. 2020. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/90440. Accessed 28 Sep 2022.

MoES. Education response plan for refugees and host communities in Uganda. Sep 2018:65. https://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/sites/planipolis/files/ressources/uganda_education-response-plan-for-refugees-and-host-communities-in-uganda.pdf.

Andrew AK. Health status and quality of health care services of Congolese refugees in Nakivale, Uganda. J Food Res. 2016;5(3):39. https://doi.org/10.5539/jfr.v5n3p39.

Ronald B. Impact of restricted access to health care among refugees in Uganda. Jun 2021.

Njenga M, Gebrezgabher S, Mendum R, Adam-Bradford A, Woldetsadik D. Circular economy solutions for resilient refugee and host communities in East Africa. Int Water Manag Inst. 2020. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.19800.52489.

McCann TV, Mugavin J, Renzaho A, Lubman DI. Sub-Saharan African migrant youths’ help-seeking barriers and facilitators for mental health and substance use problems: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0984-5.

Williams ME, Thompson SC. The use of community-based interventions in reducing morbidity from the psychological impact of conflict-related trauma among refugee populations: a systematic review of the literature. J Immigr Minor Heal. 2011;13(4):780–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-010-9417-6.

Loiacono F, Vargas MS. Improving access to labour markets for refugees: Evidence from Uganda. Oct 2019.

Krause U, Gato J. Escaping humanitarian aid in camps? Rethinking the links between refugees’ encampment, urban self-settlement, coping and peace. Die Friedens-Warte. 2019;92(1–2):76.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded through a stipend granted to the author by Katholischer Akademischer Ausländerdienst (KAAD), Germany, and by substantial subsidies from the author’s doctoral advisors Professor Ulrich Kühnen and Professor Klaus Boehnke, both at Jacobs University Bremen. The reported study is part of the author’s doctoral research project. The manuscript benefitted greatly from comments on an earlier version by the doctoral advisors and I also acknowledge reviews by Dr. Franziska Deutsch, Dr. Jens H. Hellmann, Dr. Marieke Van Egmond, Dr. Kierstyn Hunter, Dr. Catherine Koverola, Prof. Dr. Stefan Stürmer and doctoral fellow students at Bremen International Graduate School of Social Sciences.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JK conducted the FGDs, transcribed the interviews and came up with the first draft of the manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was ethically approved by the research ethics committees of Bremen International Graduate Institute of Social Sciences and Uganda Christian University. In addition, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology and the Office of the Prime Minister’s Department of Refugees in Uganda, as representatives of the Ugandan government, authorized the study. The procedures in the present study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Written consent from all the participants was obtained before data collection. All respondents had the opportunity to understand the consent form because it was interpreted and translated into the local languages used in the FGDs. Only participants aged 18 years and above took part in this study.

Competing interests

The author has no competing interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalyegira, J. Basic psychological needs satisfaction and psychological well-being of refugees in Africa. Discov Psychol 2, 40 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-022-00052-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-022-00052-4