Abstract

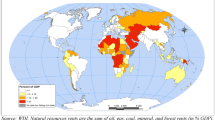

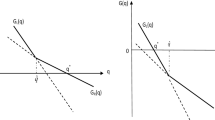

We present a model of Dutch disease in which revenue from natural resources is spent on the imports of intermediate and final goods. In the previous study of the Dutch disease model, the natural resources’ revenue is allocated only to the imports of final goods. We simulated Dutch disease according to Resource Movement Effect (RE) and Spending Effect (SE) in both primary and expanded models. The result shows that real appreciation is higher, and de-industrialization status is ambiguous if the revenue of natural resources is allocated to the imports of intermediate and final goods, and intermediate goods as an input in the production of the tradable sector. In other words, there is no guarantee that with the income of natural resources, a country will be industrialized. Real depreciation may occur if the natural resources revenue is invested in the non-tradable sector. The fluctuations of the real exchange rate in natural resource-rich countries are higher than in other countries when they are allocating revenue of natural resources to the imports of intermediate and final goods. This policy is more difficult for countries whose share of natural resources in GDP is more than 7%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in: (1) World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS, 2018). Data files are available from: https://wits.worldbank.org/. (2) Darvas (2021) ‘Timely measurement of real effective exchange rates’, Working Paper, Bruegel, 23 December 2021. Available at: https://www.bruegel.org/publications/datasets/real-effective-exchange-rates-for-178-countries-a-new-database/. (3) World Development Indicator, World Bank (2020), Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=NY.GDP.MKTP.CD&country.

Notes

-The relative price of N is \(\frac{{P_{N} }}{{P_{T} }}\). This ratio is corresponding to the real exchange rate (Corden and Neary, 1982).

-It should be noted that in Eq. (5), parameter of = 0.5, this means that the intensity of labor and capital is the same.

- We have consider K = 10. K choice is voluntary. If we select K large, the number of correlated coefficients will be reduced.

- It should be noted that when > , we have RE > 0. SE is always positive irrespective of the size of the parameters.

References

Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson J, Thaicharoen Y (2003) Institutional causes, macroeconomic symptoms: volatility, crises and growth. J Monet Econ 50(1):49–123

Anderson TL, Libecap GD (2005) Forging a new environmental and resource economics paradigm: the contractual bases for exchange. In: Workshop on Environmental Issues and New Institutional Economics, INRA-ENESAD CESAER,

Arrow KJ, Chenery HB, Minhas BS, Solow RM (1961) Capital-labor substitution and economic efficiency. Rev Econ Stat 43(3):225–250

Auty Richard M (1993) Sustaining Development in Mineral: The Resources Curse Thesis. Routledge, London

Badeeb RA, Lean HH, Clark J (2017) The evolution of the natural resource curse thesis: A critical literature survey. Resour Policy 51:123–134

Baumol WJ (1967) Macroeconomics of unbalanced growth: the anatomy of urban crisis. Am Econ Rev 57(3):415–426

Bems R (2008) Aggregate investment expenditures on tradable and nontradable goods. Rev Econ Dyn 11(4):852–883

Corden WM (1984) Booming sector and Dutch disease economics survey and consolidation. Oxford Econ Paper 36(3):359–380

Corden WM, Neary JP (1982) Booming sector and de-industrialization in a small open economy. Econ J 92:825–848

Darvas Z (2021) In: Timely measurement of real effective exchange rates. Bruegel Working Paper December, Brussels. https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/264201

David PA, Van de Klundert T (1965) Biased efficiency growth and capital-labor substitution in the US. Am Econ Rev 1:357–394

Eregha PB, Mesagan EP (2016) Oil resource abundance, institutions and growth: Evidence from oil producing African countries. Journal of Policy Modeling 38(3):603–619

EUKLEMS (2018) EU KLEMS Growth and Productivity Accounts: Statistical Module, ESA 2010 and ISIC Rev. 4 industry classification. Available from: https://euklems.eu

Fragiadakis K, Paroussos L, Kouvaritakis N, Capros P (2012) A multi–country econometric estimation of the constant elasticity of substitution. In: Final WIOD Conference: causes and consequences of globalization, groningen, The Netherlands. http://www.wiod.org/conferences/groningen/Paper_Fragiadakis_et_al.pdf

Gelb AH (1988) Oil windfalls: Blessing or curse? Oxford University Press

Ghavidel S, Narenji Sheshkalany A (2017) Cost disease in service sector. Serv Ind J 37(3–4):206–228

Goldar B, Pradhan BK, Sharma AK (2013) Elasticity of substitution between capital and labour inputs in manufacturing industries of the Indian economy. The Journal of Industrial Statistics 2:169–194

Gonzalez-Rozada M, Neumeyer PA (2003) The elasticity of substitution in demand for non-tradable goods in Latin America Case Study: Argentina. Universidad t. Di Tella Working Paper 13:27

Gylfason T, Herbertsson TT, Zoega G (1999) A mixed blessing: natural resources and economic growth. Macroecon Dyn 3(2):204–225

Gylfason T (2011) Natural resource endowment: A mixed blessing? Available at SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1766385

Herrendorf B, Herrington C, Valentinyi A (2015) Sectoral technology and structural transformation. Am Econ J Macroecon 7(4):104–133

Hodler R (2006) The curse of natural resources in fractionalized countries. Eur Econ Rev 50(6):1367–1386

International Labour Organization. (2020). ILOSTAT database [database]. Available from https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/.

Kakkar V, Yan IK (2011) Sectoral Capital-Labor Ratios and Total Factor Productivity: Evidence from Asia. Rev Int Econ 19(4):674–684

Kim DH, Lin SC (2017) Natural resources and economic development: new panel evidence. Environ Resource Econ 66(2):363–391

Knoblach M, Rößler M, Zwerschke P (2016) The elasticity of factor substitution between capital and labor in the US economy: a meta-regression analysis (No. 03/16). CEPIE Working Paper. https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/146770

Kravis IB, Heston A, Summers R (1982) World product and income: International comparisons of real gross product. The World Bank

León-Ledesma MA, McAdam P, Willman A (2010) Identifying the elasticity of substitution with biased technical change. American Economic Review 100(4):1330–1357

Lombardo G, Ravenna F (2012) The size of the tradable and non-tradable sectors: Evidence from input-output tables for 25 countries. Econ Lett 116(3):558–561

Lorenzo F, Aboal D, Osimani R (2005) The elasticity of substitution in demand for non-tradable goods in Uruguay. Inter-American Development Bank, Latin American Research Network

Mallick D (2012) The role of the elasticity of substitution in economic growth: A cross-country investigation. Labour Econ 19(5):682–694

Mehlum H, Moene K, Torvik R (2006) Institutions and the resource curse. Econ J 116(508):1–20

Mendoza EG (1992) The effects of macroeconomic shocks in a basic equilibrium framework. Staff Papers 39(4):855–889

Monga C, LIN JIY (2019) Structural transformation—overcoming the curse of destiny. The Oxford Handbook of Str Trans 6:1

Morshed AM, Turnovsky SJ (2004) Sectoral adjustment costs and real exchange rate dynamics in a two-sector dependent economy. J Int Econ 63(1):147–177

Ostry JD, Reinhart CM (1992) Private saving and terms of trade shocks: evidence from developing countries. Staff Papers 39(3):495–517

Papyrakis E, Gerlagh R (2004) The resource curse hypothesis and its transmission channels. J Comp Econ 32(1):181–193

Papyrakis E, Gerlagh R (2007) Resource abundance and economic growth in the United States. Eur Econ Rev 51(4):1011–1039

Pegg S (2010) Is there a Dutch disease in Botswana? Resour Policy 35(1):14–19

Ross ML (2007) How mineral-rich states can reduce inequality. Escaping Resource Curse 23775:237–255

Rostow WW, Rostow WW (1990) The stages of economic growth: A non-communist manifesto. Cambridge University Press, UK

Sachs J, Warner AM (1995) Natural Resources Abundance and economic growth. National bureau for Economic Research, Cambridge

Sachs JD, Warner AM (1997) Natural resource abundance and economic growth. Center for International Development and Harvard Institute for International Development, Cambridge

Sachs JD, Warner AM (1999) The big push, natural resource booms and growth. J Dev Econ 59(1):43–76

Sasaki H (2007) The rise of service employment and its impact on aggregate productivity growth. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 18(4):438–459

Stockman AC, Tesar LL (1995) Tastes and technology in a two-country model of the business cycle: explaining international comovements. American Eco Review 85(1):168–185

Takatsuka H, Zeng DZ, Zhao L (2015) Resource-based cities and the dutch disease. Res Energy Eco 40:57–84

Van der Ploeg F (2011) Natural resources: curse or blessing? J Eco Literature 49(2):366–420

Watkins MH (1963) A staple theory of economic growth. Canadian J Eco Political Sci Canadienne De Economiques Et Science Politique 29(2):141–158

World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) (2018) Available at https://wits.worldbank.org/

World Bank (2020) World Development Indicators. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators/preview/on

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the respondents for their active participation in the survey and grateful to anonymous reviewers and the editor for their valuable suggestions to improve the quality of the paper.

Funding

This study has received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm responsibility for conceptualization, methodology, design, data curation, analysis, interpretation, writing, and review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

There is no ethical conflict.

Research involves human or animal participants

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to the publication

The authors give consent for the publication of the paper.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghavidel Doostkouei, S., Azizi, K. & Talaneh, A. Can natural resources revenue start industrialization? (A model for Dutch disease). SN Bus Econ 3, 22 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-022-00379-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-022-00379-z