Abstract

This paper reports on a survey exploring whether police prosecutors in the Queensland Police Service can recognise and respond appropriately to intimate partner violence (IPV) in the LGBTIQ community. Utilising an online survey featuring hypothetical vignettes of IPV involving LGBTIQ people, it sought to understand police prosecutors’ recognition of, and response to, IPV situations involving LGBTIQ people; the likelihood of IPV occurring in LGBTIQ relationships; and whether friendships, interaction (social and professional), and levels of trust in LGBTIQ people shape their perceptions of LGBTIQ victims, perpetrators, and IPV itself. Contributing new knowledge into the extant policing literature examining policing of IPV, the results of this study offer a unique insight into police prosecutors and LGBTIQ IPV and their inability to clearly distinguish between perpetrators and victims in LGBTIQ IPV scenarios, particularly where coercive control is involved, or a transgender person is the victim. We argue that enhancing police prosecutors’ recognition of, and response to, IPV situations in the LGBTIQ community is important because of the key role that prosecutors play in LGBTIQ peoples’ access to justice and responding appropriately to their needs as victims and perpetrators. The results from this study have international significance regarding developments in policing policy and practice and IPV recognition, and what this means for operational policing guidelines and better policing response when prosecuting IPV situations involving LGBTIQ people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Australia, a significant body of commentary and research literature has emerged in recent years detailing intimate partner violence (IPV) as experienced by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and queer (LGBTIQ) people (see Donovan & Barnes 2020; Miles-Johnson 2020; Ovenden et al. 2019). Whilst estimates of the extent of such violence vary, some studies suggest that such violence occurs at least at the same level as IPV in cisgender, heterosexual relationships (see Ovenden et al. 2019). This emerging research, and growing concern about the issue amongst LGBTIQ communities has led to growing recognition of the importance of addressing this violence, and critical evaluations of societal and policing responses. Up until the last decade, societal responses have been based on cisnormative and heteronormative frameworks that see IPV as predominantly perpetrated by cisgender and heterosexual men against cisgender and heterosexual women (Donovan & Barnes 2020). Societal responses to IPV include increased efforts by key actors in the criminal justice system, policy makers and legislators to recognise the scope of the problem of IPV in heterosexual cisgender relationships, thereby framing it as a social crisis, and increasing initiatives to combat IPV within communities. Societal responses also include increased initiatives to criminalise perpetrators of IPV, systematic reviews of the methods by which IPV is addressed, as well as analysing current initiatives and resources in place to do so, and, recognising the impact IPV has on the victim, family members, and other members of society in general (Buzawa and Buzawa 2017). Whilst societal responses to IPV based on heterosexual cisgender relationships certainly reflect the perceptions of many first responders to IPV crimes in Australia, these frameworks do not adequately reflect LGBTIQ experiences or equip police or service providers to respond to the unique needs of these communities in IPV situations (Morgan et al. 2018),

Considerable scholarly attention and advocacy efforts have been directed towards understanding the role of these heteronormative and cisnormative frameworks in shaping the response of policing services when dealing directly with an incident of IPV experienced by LGBTIQ people (see Barnes 2013; Carrington 1999; Donovan & Barnes 2020; Finneran & Stephenson 2012; Morgan et al. 2018; Ovenden et al. 2019). The way that frontline police recognise and respond to such violence (including whether they even recognise it as a crime) has significant impacts on the experience of justice for LGBTIQ victims (Broderick 2011; Morgan et al. 2018). This includes the inability of police officers to implement effective responses that target LGBTIQ IPV, as well as the inability of police officers to identify different forms of physical and/or psychological abuse experienced by LGBTIQ victims of IPV, because policing responses to IPV and typologies of IPV are based on heterosexual cisgender models of IPV (Langenderfer-Magruder et al. 2016; Miles-Johnson 2021). Significant impacts also include a misplaced focus by police officers regarding victim and perpetrator status of LGBTIQ individuals involved in IPV, as well as limitations imposed by heteronormative, or cisgender specific services offered to victim-survivors of IPV. This is also because victim and perpetrator roles and subsequent support services are based on heterosexual cisgender standards of IPV (Langenderfer-Magruder et al. 2016; Miles-Johnson 2021). Furthermore, to date, research has largely focussed on the response of frontline police officers, with less attention having been paid to recognition of, and responses to, LGBTIQ IPV by police and other agents of criminal justice in the later stages or components of criminal justice processes.

Whilst the focus on frontline police responses to IPV in LGBTIQ contexts is certainly important, this paper moves beyond that to explore another key component of the criminal justice response to this crime, and one that hitherto has been unexplored—the work of police prosecutors. This study sought to explore whether Queensland Police Service (QPS) police prosecutors can recognise and respond appropriately to IPV in the LGBTIQ community, particularly by assessing the current knowledge, understanding, and insight of QPS prosecutors regarding the diverse and unique contexts and dynamics of LGBTIQ IPV. The paper argues that enhancing police prosecutors’ recognition of, and response to, IPV situations in the LGBTIQ community is important because of the key role that prosecutors play in shaping the access that LGBTIQ people have to criminal justice. No other public-service agency has the capacity to discriminate against LGBTIQ people in the same way as police organisations. If police prosecutors view IPV situations through heteronormative and cisgender lenses that are neither appropriate for, nor tailored towards, LGBTIQ experiences of IPV, then those prosecution officers are likely to not only be less effective in their capacity to prosecute IPV offenders in these contexts, but also less able to respond appropriately to the needs of LGBTIQ perpetrators and victims. The results also suggest that male and female prosecution officers, and officers aged between 18 and 33 years of age differ in their ability to recognise perpetrators and victims of IPV in LGBTIQ relationships. Contributing new knowledge into the extant policing literature examining policing of IPV, the results of this study offer a unique insight into police prosecutors and LGBTIQ IPV and their inability to clearly distinguish between perpetrators and victims in LGBTIQ IPV scenarios.

Why recognition of, and response to, LGBTIQ IPV matters

In Australia, IPV experienced by LGBTIQ people has long been overlooked in societal and policing responses to these crimes (Broderick 2011; Donovan & Barnes 2020). In recent years, attention to this issue has slowly grown (see Donovan & Barnes 2020; Miles-Johnson 2020; Ovenden et al. 2019). Whilst no studies on this issue can claim to be fully representative or generalisable, several studies have indicated that 33% of LGBTIQ people have been in an abusive relationship (Pitts et al. 2006) and that IPV occurs in LGBTIQ relationships at least at a rate that is like heterosexual cisgender people (Irlam 2013). There is a small body of research that critically evaluates police responses to LGBTIQ IPV (see Broderick 2011; Franklin et al. 2019; Langenderfer-Magruder 2016; Miles-Johnson 2020; Natarajan 2016; Russell & Sturgeon 2019; Saxton et al. 2018). These studies have consistently identified police responses as inadequate both in supporting victims appropriately and in responding to the violence that they experience. They have also identified several intersecting reasons that this occurs, including the limited frameworks through which IPV is understood by officers; the limited experience, awareness, and training that police officers often have in responding appropriately to the specific needs of LGBTIQ people; and the way that historically strained relationships between police and the LGBTIQ community impact on their current interactions (Broderick 2011; Franklin et al. 2019; Langenderfer-Magruder 2016; Miles-Johnson 2020; Natarajan 2016; Russell & Sturgeon 2019; Saxton et al. 2018). We consider these issues briefly below and then move on to highlight the specific research gap that this study addresses.

Research identifies that one of the reasons for problematic policing responses to IPV experienced by LGBTIQ people is the inability of officers to fully understand and recognise the existence of violence in LGBTIQ relationships (Broderick 2011; Franklin et al. 2019; Langenderfer-Magruder 2016; Miles-Johnson 2020; Natarajan 2016; Russell & Sturgeon 2019; Saxton et al. 2018). This is partly due to the limited awareness of this issue in society more broadly (Donovan & Barnes 2020) and reinforced by the dominant experiences that police officers have when responding to IPV. Whilst police respond to incidents of LGBTIQ IPV, police officers respond more frequently to IPV in heterosexual cisgender relationships, and as such, expect IPV to occur in heterosexual cisgender contexts (Russell & Sturgeon 2019).

There are many similarities in IPV as experienced by LGBTIQ and cisgender heterosexual people, but there are also important differences that present unique challenges for policing responses (Saxton et al. 2018). LGBTIQ IPV can involve different forms of social and/or psychological abuse and control such as the threat to ‘out’ (i.e. disclose to family, friends, or colleagues) a person’s identity as LGBTIQ or (for people involved in high-risk HIV relationships) their HIV-positive serostatus (Russell & Sturgeon 2019; Saxton et al. 2018). Perpetrators may withhold (or threaten to withhold) HIV medications or hormones related to one’s gender affirmation from their partners (Whitton et al. 2016). Perpetrators have also been known to mobilise forms of homophobia and transphobia to coercively control or to abuse their partners (Miles-Johnson 2020). This includes upholding negative stereotypes of behaviour associated with heterosexual relationships or heterosexual gender roles, thereby refuting, or not recognising non-heterosexual or non-cisgender elements (Russell & Sturgeon 2019). These unique forms of violence and control require specific responses from police, such as their taking seriously these novel forms of violence and coercive control as forms of violence and control (Franklin et al. 2019). Without recognising these nuances within LGBTIQ relationships, police may continue to hold heteronormative and cisnormative expectations of the behaviour of perpetrators and victims (Saxton et al. 2018).

The frameworks through which police officers understand IPV may also be reinforced by their experiences in responding to and prosecuting IPV incidents. Whilst no two incidents of IPV are the same, most police officers perceive violence is perpetrated by cisgender heterosexual men towards cisgender heterosexual women (Broderick 2011; Decker, Littleton & Edwards 2018). This means that frontline general duties police officers most frequently respond to incidents of IPV wherein the parties’ identities, relationships, and domestic settings resemble heteronormative cisgender relationships (Decker et al. 2018). This contributes to, and reinforces, the heteronormative and cisnormative frameworks that dominate what forms of IPV are taken seriously, how IPV is understood by police officers, and what responses are deemed appropriate (Miles-Johnson 2020). The power of such experiences in shaping police understandings of IPV may prevent the development of more responsive approaches, tailored to the experiences, and needs of LGBTIQ people.

Police experience with, awareness of, and training in LGBTIQ issues

Research suggests that police often have limited professional experiences with LGBTIQ people, and as such, have limited awareness of the diverse needs of these communities, and are also limited in the amount of training they receive regarding respectful and appropriate communication with LGBTIQ people (Decker et al. 2018; Franklin et al. 2019). Whilst numerous pieces of research suggest that LGBTIQ people purposefully avoid having contact with police because of fear of poor treatment and the perceived lack of appropriate response that they will receive from police officers (see Alliance for a Safe and Diverse DC 2008; Berman and Robinson 2010; Edelman 2014; Heidenreich 2011; Miles-Johnson 2021; Redfern 2014; Wolff and Cokely 2007), the lack of experience police officers have with LGBTIQ people raises questions regarding whether they would be able to interact appropriately with LGBTIQ perpetrators and victims of IPV, and adequately respond to IPV in these contexts. As the bulk of officer experiences with IPV involve heterosexual and cisgender people, for some officers an incident of IPV involving members of the LGBTIQ community may in fact be the first time that they have interacted with a member of these communities, let alone in a policing context (Miles-Johnson 2020).

Limited experience dealing with LGBTIQ communities impacts officers’ abilities to adequately recognise and respond to an IPV incident, particularly because they are less likely to be aware of the array of identities and relationship dynamics that exist within LGBTIQ communities, and appreciate the need for tailored methods of communication (such as being sensitive to the privacy concerns of LGBTIQ people to ensure they are not inadvertently ‘outed’ by a policing response, or being respectful of the pronouns of the people involved) (Decker et al. 2018; Franklin et al. 2019). Russell and Sturgeon, (2019), Saxton et al. (2018), and Miles-Johnson, (2020) argue that police officers are generally unprepared when responding to an incident of IPV involving LGBTIQ people and do not possess an adequate knowledge base regarding perpetrators and victims of LGBTIQ IPV. Existing studies of police responses to LGBTIQ IPV suggest that the quality of the service that LGBTIQ people receive from police is entirely dependent on the awareness of the attending officer and the specific needs of the victims, as well as the ability of the officers involved to recognise the different contexts and situations where LGBTIQ IPV can occur (Broderick 2011; Franklin et al. 2019; Langenderfer-Magruder 2016; Miles-Johnson 2020; Natarajan 2016; Russell & Sturgeon 2019; Saxton et al. 2018).

Research has also pointed out that any discussion of the police response to IPV in the LGBTIQ community must consider how relations between the LGBTIQ community and police are structured by the homophobia and transphobia that LGBTIQ people have historically experienced at the hands of police and criminal justice agents (Donovan & Barnes 2020). This directly impacts on the likelihood that victims will contact police in response to IPV as well as the way in which police officers recognise and respond to IPV with members of the LGBTIQ community (see Broderick 2011; Franklin et al. 2019; Langenderfer-Magruder 2016; Miles-Johnson 2020; Natarajan 2016; Russell & Sturgeon 2019; Saxton et al. 2018). Despite the repeal of discriminatory laws, and the significant efforts by police and community organisations to improve these relationships, LGBTIQ people still report homophobia and transphobia in their interactions with police or are still hesitant to engage with police out of a fear that they will experience such discrimination (See Dwyer et al. 2017). As such, successful efforts to build relationships between police and LGBTIQ communities in Australia remains fragile and often lacks the broader organisational support within policing organisations that would enhance their prospects for success (Dwyer et al. 2017; Miles-Johnson 2020; Russell & Sturgeon 2019).

These factors mean that victims and perpetrators of LGBTIQ IPV will be underserved by the criminal justice system and remain at risk of further violence if they are unable to seek or receive adequate support (Decker et al. 2018; Franklin et al. 2019). Importantly, many existing studies focus primarily on the response of frontline police who are attending IPV incidents (Saxton et al. 2018). Such a focus is understandable, because it is frontline officers who immediately respond to incidents and whose decisions and practices determine which incidents will be taken seriously enough to be drawn into criminal justice processes (Mbuba 2021). However, comparatively little is known about the attitudes and responses of other criminal justice agents towards IPV in LGBTIQ contexts. One key group to consider in this context, which forms the focus of this current study, is police prosecutors.

Police prosecutors and LGBTIQ IPV

In the Australian context, whilst it is the job of the arresting officer to determine whether an offence has been committed, the responsibility to prosecute IPV-related charges rests with police ‘prosecutors’ employed by each Australian state police organisation (Mbuba 2021). It is the information provided by the arresting officer (such as the circumstances under which the offence was committed, a summary of the facts relating to the incident, and a clear definition of who is the perpetrator and who is the victim) that informs the police prosecutor’s case (OPM QPS 2021). The prosecution officer is then required to consider commencement of proceedings and ensure that there is clear information and adequate instructions regarding whether an offence of IPV has been committed, the charge of IPV is able to be proven, any relevant defences can be negated, and admissible evidence to substantiate the charges of IPV can be presented when necessary (OPM QPS 2021). A successful prosecution relies not only on the quality of the information provided by the arresting officer, but also the prosecutor’s own judgement relating to these issues (OPM QPS 2021).

By focussing on police prosecutors, this study addresses a gap in the existing research, drawing attention to prosecutors and LGBTIQ IPV as an important component in shaping criminal justice responses to these crimes. We suggest that if officers working in the QPS prosecutions team can accurately recognise incidents of IPV experienced by members of the LGBTIQ community and can recognise perpetrators and victims of IPV in LGBTIQ relationships, then it is reasonable to suggest that this will have a positive impact in terms of improving the prosecutorial capabilities of the QPS in relation to LGBTIQ IPV abuse across Queensland. Improved prosecutorial capabilities of the QPS and the LGBTIQ community are also likely to assist in the development of effective relationships with internal and external partners working with the QPS to specifically assist LGBTIQ people in IPV situations and enhance subsequent legal proceedings (and the experience of LGBTIQ people) as they progress through legal processes and family violence specialist courts. Hitherto this study, research examining police prosecutors and IPV in LGBTIQ relationships has been overlooked in much of the extant policing literature regarding policing of IPV and LGBTIQ people.

Methods

Online survey

To understand how police prosecutors recognise and respond to IPV involving LGBTIQ people, QPS police prosecutors working in the state-wide prosecutions team in Queensland were strategically targeted to complete an online survey. The survey featured four hypothetical vignettes of IPV involving members of the LGBTIQ community, to better understand: police prosecutors regarding their recognition of and response to hypothetical IPV situations involving LGBTIQ people; the likelihood of IPV occurring in LGBTIQ relationships; and whether friendships, interaction (social and professional), and levels of trust in LGBTIQ people shape their perceptions of LGBTIQ victims, perpetrators, and IPV itself.

Survey recruitment

Online surveys with groups such as the police offer substantial benefit regarding completion over other data collection methods since police officers are usually time-poor and managing shift work of interchangeable hours of attendance in court, which typically make in-person interviews difficult (Miles-Johnson 2020). Because each member of the research team has no professional affiliation with, or is employed by the QPS, once the survey was developed by the research team and approved by senior officers in the organisation, the QPS emailed an invitation to participate in the survey (as well as the link to the online survey) to all the state-wide members of the prosecutorial team (as per the QPS’s own guidelines for conducting research). In accordance with our university’s research ethics approvalFootnote 1 and under the research stipulations of the QPS, no members of the state-wide prosecutions team would be coerced into participating in the study, and all collected data would be anonymous and confidential.

At the start of the online survey, all participants were informed via the participant information page that their responses were anonymous and would not impact their professional relationship with the QPS. The participants were informed that completion of the survey would take approximately 15–20 min. As part of the research agreement with the QPS, only general demographic data (such as gender, age, sexuality, Aboriginal identity, and relationship status) of the participating officers would be collected, since specific demographic information such as geographical location, name, badge number, rank, and time in the role as a QPS prosecutor could potentially identify the participants.

Survey response rates

Whilst there were no expectations regarding the final number of participants, there are approximately 400 prosecutors working within the QPS across the state of Queensland, and since participants for the research were recruited by the QPS, it was unknown at the onset of data collection how many members of the prosecutions team would participate in the research. It was, however, anticipated that at least 100 prosecutors would participate in the research. Whilst that might be considered a small sample, Brick and Kalton (1996) suggest that successful statistical analysis of the results of a small sample is still possible. They argue that one way of dealing with a lack of representativeness is to consider the sample in relation to the greater population attributes, and that a response rate of 25% is acceptable if there is 100% completion. In total, 108 members of the QPS state-wide prosecutions team participated in the survey (N = 108, 27% response rate) and all responses were complete.

Survey items

The items in the online survey were adapted from previous research conducted by the research team.Footnote 2 Each item in the survey was strategically placed to better understand police prosecutors’ recognition of, and response to, hypothetical IPV situations involving LGBTIQ people, and the likelihood of IPV occurring in LGBTIQ relationships. This included placing items in the survey in an order that reflects the systemic and chronological policing processes that police prosecutors use when investigating crime, thereby reflecting prosecutorial processes, situations, and contexts that are familiar to the participants. The items in the survey also asked participants: whether friendships, interaction (social and professional), and levels of trust in LGBTIQ people shape their perceptions of LGBTIQ IPV; and sought to understand their perceptions of LGBTIQ perpetrators and victims of IPV.

In this study, we utilised the acronym LGBTIQ to refer to anyone who identifies as: non-heterosexual; as not identifying with the sex assigned to them at birth (i.e. not cisgender); as intersex; or as queer. We acknowledge that sexuality and gender diversity can be defined in many ways, can be measured utilising many variables, and that there is significant debate about how best to represent sexually and gender diverse communities in research.Footnote 3 We determined that, for the purposes of this research, members of the LGBTIQ community would be placed into a homogenous group. First, whilst there are important differences between these groups and their experiences (for example, gender diversity and sexual orientation are different characteristics), these groups are still interconnected by virtue of their sexual and gender identities (as members of the LGBTIQ community) and as such, are identified as different from heterosexual and cisgender identities that are positioned as social norms (see Ghaziani 2011). We also recognise that, as Canales (2000) states, positioning LGBTIQ people as a homogeneous group may reinforce the “othering” of these sexual and gender identities (particularly by agencies such as the police), grouping these identities in such a way also reflects how they are categorised socially and understood by many members of these communities themselves. Whilst collectively grouping LGBTIQ people in this way would result in the heterogeneity of LGBTIQ people’s experiences of IPV and therefore somewhat limit the generalisability of the study, it was anticipated that the results of this study would still allow us to speak to the broader issues regarding police prosecutors and LGBTIQ IPV, and potentially form the basis for more targeted research with specific groups.

Hypothetical vignettes

This study used hypothetical vignettes to allow the participants to imagine themselves responding to different IPV scenarios and then answering various questions or stimuli (Miles-Johnson et al. 2018). Whilst it may be argued that hypothetical vignettes may not be comparable to data collected in real-life situations, research by Miles-Johnson et al. (2018) found a strong correlation between intentions captured by hypothetical vignette research and real-life behaviour. Ensuring that such vignettes reflect situations and contexts that are familiar to participants also minimises any limitations produced by their use in research (Miles-Johnson et al. 2018). For example, vignettes based on real-life situations are less likely than fictional vignettes to shift a participant’s focus from a fictional situation to their own views and ideas (O’Dell et al. 2012). It also reduces the likelihood that participant responses will reflect socially desirable responses rather than honest predictions or representations of their own behaviours (O’Dell et al. 2012).

There are, however, several limitations associated with online studies and perception. For example, when using online surveys to capture perceptions it is important to acknowledge that non-sampling errors may occur if participants provide intentionally or unintentionally incorrect answers to each question. It is also important to note that items capturing perception within surveys can yield different responses, and that social desirability could affect the responses given by participants regarding their perception of situations. Perception bias could also affect the outcome of participant’s responses to the vignettes because they rely heavily on inference, and as such, there may be differences between participants perceived beliefs and actions regarding what people think they would do in a given situation and their actual behaviour (Hughes & Huby 2004). Whilst no single research method can completely capture the nature of perception, it is important to note that the use of online surveys in numerous pieces of research have been used successfully to understand perceptions of police regarding citizen engagement (see Hacker & Horan 2019; Miles-Johnson 2021; Pickles 2019) and police perceptions of crime and victimisation (see Gerstner 2018; Lewandowski et al. 2018; Santos 2018). In addition, the use of hypothetical vignettes to capture perception are widely used in quantitative and qualitative research, particularly in cross-cultural research analysing perceptions of real-life scenarios (Erfanian et al. 2020).

Therefore, in collaboration with senior officers from the QPS, four hypothetical vignettes were constructed based on real-life incidents of IPV previously recorded by police officers working in the QPS (see Appendix A). Each of the hypothetical vignettes focussed on different types of IPV, with varying levels of intensity, including verbal abuse and physical abuse (Scenario 1), financial abuse and coercive control (Scenario 2), sexual abuse (Scenario 3), and sexual and identity abuse (Scenario 4). As stated, policing responses to IPV and typologies of IPV are based on heterosexual cisgender models of IPV and police officers often fail to identify different forms of physical and/or psychological abuse experienced by LGBTIQ victims of IPV, because policing responses to IPV and typologies of IPV are based on heterosexual cisgender models of IPV (Miles-Johnson 2021). As such, Scenario 1 (verbal and physical abuse) was intentionally created to challenge participants’ recognition of the perpetrator and victim and type of IPV. The vignettes also incorporated different LGBTIQ identities within the relationships described, to account for the diversity of LGBTIQ identities and relationships that exist and may be encountered when responding to IPV: two included two cisgender women; one included two cisgender men; and one included a transgender woman and a cisgender man who, in the vignette, identifies as heterosexual. Scenario 1 was intentionally created to challenge participants’ recognition of the perpetrator and victim,

Each hypothetical vignette was followed by fixed survey items, identically measuring how the participants would respond to each incident of IPV involving members of the LGBTIQ community. Survey items also measured: the participants’ perceptions of the likelihood of IPV occurring in LGBTIQ relationships; and whether friendships, interaction (social and professional), and levels of trust in LGBTIQ people shape their perceptions of LGBTIQ IPV, LGBTIQ perpetrators, and LGBTIQ victims (Appendix B). Items in the survey specifically asked the participants whether they could correctly identify the parties involved in each hypothetical scenario, such as the perpetrator and the victim. The items also asked whether the participants would proceed with the prosecution or withdraw the matter from legal processes, whether they would be uneasy interviewing the perpetrator or the victim, whether they would prosecute the perpetrator in the vignette, and whether they would rather reallocate the case to another police prosecutor (given the victim’s or the perpetrator’s identity as a member of the LGBTIQ community).

Independent variables

Nine scales analysing the respondents’ recognition of, and response to, the hypothetical vignettes were created from the items within the survey and were used to create independent variables and scales for analyses. Since the title of each scale was too long to include in the analysis, each scale was given a unique identifier or number ranging from one to nine (1–9). These included the following:

-

Scale 1 (recognition of LGBTIQ Male Perpetrator in comparison to Heterosexual Male Perpetrator and Female LGBTIQ/Heterosexual Victim Scale – four items, Cronbach Alpha 0.64).

-

Scale 2 (recognition of LGBTIQ Female Perpetrator in comparison to Heterosexual Female Perpetrator and Male Victim LGBTIQ/Heterosexual Scale – four items, Cronbach Alpha 0.70).

-

Scale 3 (recognition of LGBTIQ Female Victim Behaviour in comparison to Heterosexual Female Victim Behaviour and Male Perpetrator LGBTIQ/Heterosexual Scale – four items, Cronbach Alpha 0.73).

-

Scale 4 (recognition of LGBTIQ Male Victim Behaviour in comparison to Heterosexual Male Victim and Female LGBTIQ/Heterosexual Perpetrator Scale – four items, Cronbach Alpha 0.71).

-

Scale 5 (LGBTIQ Close Friends Influence on Perception Scale – six items, Cronbach Alpha 0.77).

-

Scale 6 (LGBTIQ Socialisation and Community Contact Scale – six items, Cronbach Alpha 0.62).

-

Scale 7 (LGBTIQ Professional Contact and Community Engagement Scale – 12 items, Cronbach Alpha 0.85).

-

Scale 8 (Trust in LGBTIQ People Scale – nine items, Cronbach Alpha 0.70); and,

-

Scale 9 (LGBTIQ People and Likelihood of Involvement in IPV Scale – four items, Cronbach Alpha 0.62).

All the scales either had acceptable or good internal consistency and were determined to be measuring the same underlying characteristic regarding perceptions of IPV. As a result, each of the independent variables were used in the analyses. The minimum and maximum score for each scale is shown in Table 1.

Results

Participants

The participants ranged from 23 to 57 years of age (M = 37.7, SD = 8.03). Most participants identified as male (76.9%) as compared to female (23.1%), and most participants identified as heterosexual (91.7%), as opposed to gay (6.5%) or lesbian (1.9%). All the participants identified as cisgender or indicated that their gender aligned with the sex assigned to them at birth. Two participants identified as AboriginalFootnote 4 (0.9%), and no participants identified as a member of another minority racial or ethnic group, and most participants stated that they were in a relationship at the time of the survey (68.5%). The participant’s demographics by gender, sexuality, Aboriginal identity, and relationship status are shown in Table 2.

Statistical analysis

To examine police prosecutors’ recognition of, and response to, hypothetical IPV situations involving LGBTIQ people, the likelihood of IPV occurring in LGBTIQ relationships, and whether friendships, interaction (social and professional), and levels of trust in LGBTIQ people shape their perceptions of LGBTIQ IPV and LGBTIQ perpetrators and victims, a series of non-parametric statistical analyses tests were applied to the data. Since the data are unevenly distributed (with more male than female, and more heterosexual than LGBTIQ respondents) a Mann–Whitney U Test and a series of Kruskal–Wallis H tests were applied to the analyses. Since non-parametric statistical analysis techniques were used in this study, the participants’ gender (cisgender male/cisgender female), age (collapsed into three groups, 18 to 33 years of age, 34 to 41 years of age, and 42 and above years of age), and sexuality (collapsed gay/lesbian identity) were interchanged as the dependent variable. Since the number of police prosecutors identifying as a member of the Aboriginal community was less than one percent it was decided that this would not be included in the final analyses.

Mann–Whitney U test and participant’s gender

When the participants’ gender (cisgender male/cisgender female) was used as the dependent variable in the Mann–Whitney U test, the results indicated that apart from Scale 6 (LGBTIQ Socialisation and Community Contact Scale) U = 813.50, z = − 1.78, p = 0.07, r = 0.1, there was a significant association between gender and each of the variables in relation to their recognition of, and response to, the hypothetical vignettes. Whilst each of the other variables were significant regarding the gender of the prosecutor in relation to their recognition of and response to LGBTIQ IPV, the participants’ gender had a large effect on four of the variables. This included a large effect on their perceptions of 1) LGBTIQ Male Perpetrators in comparison to Heterosexual Male Perpetrators and Female LGBTIQ/Heterosexual Victims, 2) their perceptions of LGBTIQ Female Perpetrators in comparison to Heterosexual Female Perpetrators and Male LGBTIQ/Heterosexual victims, 3) their perceptions of LGBTIQ Female Victim Behaviour in comparison to Heterosexual Female Victim Behaviour and Male LGBTIQ/Heterosexual Perpetrators, and 4) their perceptions of LGBTIQ Male Victim Behaviour in comparison to Heterosexual Male Victim Behaviour and Female LGBTIQ/Heterosexual Perpetrators.

The significance of gender in these results may be related to the greater number of male officers than female officers comprising the sample – an overrepresentation that reflects the demographics of most police organisations. Across Australia, police organisations employ more male officers than female officers, and this is reflected in the QPS generally as well as in the QPS prosecutions team. Inspection of the median scores for each variable, however, indicate that male officers scored higher than female officers on:

-

Scale 1 (recognition of LGBTIQ Male Perpetrator in comparison to Heterosexual Male Perpetrator and Female LGBTIQ/Heterosexual Victim Scale),

-

Scale 2 (recognition of LGBTIQ Female Perpetrator in comparison to Heterosexual Female Perpetrator and Male Victim LGBTIQ/Heterosexual Scale),

-

Scale 3 (recognition of LGBTIQ Female Victim Behaviour in comparison to Heterosexual Female Victim Behaviour and Male Perpetrator LGBTIQ/Heterosexual Scale), and,

-

Scale 4 (recognition of LGBTIQ Male Victim Behaviour in comparison to Heterosexual Male Victim and Female LGBTIQ/Heterosexual Perpetrator Scale).

This suggests that male officers are less likely than female officers to recognise the behaviour of the perpetrator as IPV if the perpetrator was a male from the LGBTIQ community than they are when the same behaviour is perpetrated by a heterosexual man against a heterosexual woman. The male officers are also less likely than the female officers to recognise the behaviour of the perpetrator as IPV if the perpetrator was a female from the LGBTIQ community than they are when the same behaviour is perpetrated by a heterosexual woman against a heterosexual man. Additionally, male officers are less likely than female officers to recognise the victim as experiencing victimisation if the victim was a female from the LGBTIQ community than they are if the female victims are heterosexual females. They are also less likely than female officers to recognise the victim as experiencing victimisation if the victims are males from the LGBTIQ community than if the victim are heterosexual males. Female officers scored slightly higher than male officers on:

-

Scale 5 (LGBTIQ Close Friends Influence on Perception Scale),

-

Scale 7 (LGBTIQ Professional Contact and Community Engagement Scale), and,

-

Scale 9 (LGBTIQ People and Likelihood of Involvement in IPV Scale),

This suggests that female officers are more likely than male officers to have close friendships with members of the LGBTIQ community, more likely than male officers to have been involved in professional contact and community engagement with LGBTIQ people, and more likely than male officers to recognise that LGBTIQ people will be involved in an IPV situation. The police prosecutors’ gender and its effect on their recognition of, and response to LGBTIQ IPV are shown in Table 3.

Kruskal–Wallis H Test and Participant’s Sexuality

The Kruskal–Wallis H Test revealed that the sexuality of the participants was not significant in relation to Scale 6 (LGBTIQ Socialisation and Community Contact Scale) X2 = 7.22, p = 0.06. This may be because the number of participants in this study identifying as heterosexual outnumbered the small number of participants identifying as gay or lesbian, and many of the heterosexual participants indicated they do not socialise with members of the LGBTIQ community. Whilst the participants’ sexuality had a significant influence on all the other scales and the police prosecutors’ recognition of, and response to LGBTIQ IPV, this is likely due to the uneven distribution of the heterosexual versus lesbian and gay participants (91.7% of the sample identified as heterosexual).

In addition, the Kruskal–Wallis H Test revealed that the age of the participants was significant in relation to each of the variables apart from Scale 6 (LGBTIQ Socialisation and Community Contact Scale) X2 = 3.17, p = 0.21, Scale 8 (Trust in LGBTIQ People Scale) X2 = 0.66, p = 0.72, and Scale 9 (LGBTIQ People and Likelihood of Involvement in IPV Scale) X2 = 5.68, p = 0.06. This suggests that the age of the officer does not have an effect on the officer’s friendships with LGBTIQ people (since many of the participants indicated that they do not socialise with LGBTIQ people); it does not affect their trust in LGBTIQ people; and the age of the participants does not influence the likelihood they will recognise that LGBTIQ people can be involved in IPV. Whilst the age of participants was significant in relation to Scale 1, Scale 2, Scale 3, Scale 4, Scale 5, and Scale 7, when each of the age categories were considered, the results suggest participants aged between 18 and 33 years of age are less likely than other participants to recognise a male or female LGBTIQ perpetrator of IPV than they are to recognise a heterosexual male or female perpetrator of IPV. They are also less likely to recognise a male or female LGBTIQ victim of IPV than they are to recognise a male or female heterosexual victim. Participants aged between 34 and 41 years of age are more likely to report having close friends with people from the LGBTIQ community than participants in the other age groups, and, regardless of age, all members of the prosecutorial team reported that they were likely to have the same amount of professional contact and community engagement with members of the LGBTIQ community. The police prosecutor’s age and sexuality, and their effect on recognition of, and response to LGBTIQ IPV, are shown in Table 4.

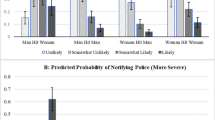

Participant’s recognition of perpetrators and victims in the hypothetical LGBTIQ IPV situations

In addition to the series of non-parametric statistical analyses, the results were also analysed using descriptive statistics to determine whether (after having read the hypothetical LGBTIQ IPV situations) police prosecutors could correctly identify the perpetrator and the victim in each vignette. Descriptive statistics were also used to determine whether the police prosecutor would proceed with the prosecution, withdraw the matter from legal processes, whether they were uneasy interviewing the perpetrator or the victim, whether they would prosecute the perpetrator, and whether they would rather reallocate the case to another police prosecutor (given the victim’s or the perpetrator’s identity as a member of the LGBTIQ community).

The analysis of the descriptive statistics revealed that whilst most of the participants could correctly identify the perpetrator (Sharon) and the victim (Lisa) in Scenario 2 (cisgender lesbian relationship) and the perpetrator (Mark) and the victim (Todd) in Scenario 3 (cisgender gay relationship), many of the participants were unsure of the perpetrator and victim in Scenario 1 (cisgender lesbian relationship), and incorrectly identified the perpetrator and victim in Scenario 4 (transgender woman and heterosexual man). As stated, Scenario 1 was intentionally created to challenge participants’ recognition of the perpetrator and victim, though it is important that prosecutors recognise that the report is made by the aggrieved in this scenario (Bev) who is identified as the victim (until further investigation suggests otherwise). Given that Bev reports her fear of Judy, a physical assault has occurred, and there is a reported history of abuse, it is likely that Bev is the victim and Judy is the perpetrator. Whilst the perpetrator and victim roles are clearly described in the situation in Scenario 4, the inability of many of the prosecutors to correctly identify the perpetrator and victim in that scenario raises questions about why some of the prosecutors perceived John (the perpetrator) as the victim, and whether this bias may be linked to Nat’s (the victim) identity as a transgender woman. This result will be examined further in the discussion section. The police prosecutor’s identification of perpetrator and victim in each of the hypothetical scenarios and prosecution of LGBTIQ IPV are shown in Table 5.

IPV recognition and response

Almost all the participants clearly identified that each of the hypothetical LGBTIQ IPV scenarios contained enough evidence of IPV and that the matter should not be withdrawn from legal proceedings. Yet whilst they were able to determine the criminal nature of the crimes involved in each of the hypothetical situations, as well as the type and seriousness of the offences, many of the participants gave mixed responses regarding whether to proceed with a prosecution in Scenario 2 (with over half of the sample indicating that they would not proceed with a prosecution in this situation), Scenario 3, and Scenario 4 (with just under half of the sample indicating that they would proceed with a prosecution in both of these situations). Whilst most prosecutors would proceed with a prosecution, the inconsistency in the responses regarding in which scenarios they would do so may be related to the nature of the crime and the evidence that is presented within each of the scenarios.

Interaction with IPV perpetrators or victims

The participants’ responses were also quite varied regarding their unease with interviewing an LGBTIQ perpetrator or victim in an IPV situation. Many participants’ responses suggest that they were more comfortable when they clearly identified the perpetrator and the victim (Scenario 2, 3, and 4), but the mixed responses raise questions about the potential biases of the participants that may relate to the sexuality or gender of the perpetrator and victim, and the nature of the crime in the context of LGBTIQ relationships. Whilst participants clearly indicated that they would proceed with the prosecution of the perpetrators in Scenarios 1 and 3, it is notable that the nature of the coercive control offence in Scenario 2 resulted in most of the participants choosing to not proceed with the prosecution of the perpetrator. Interestingly, participants’ responses to Scenario 4 indicate that the sample is split regarding whether to proceed with a prosecution. This raises questions about how the IPV situation outlined in that vignette and the identities of the parties involved (specifically the transgender identity of the victim and the cisgender identity of the perpetrator) may have shaped participant responses. This result will be examined further in the discussion section.

Response to IPV case reallocation

When asked whether the participants would rather reallocate the case to another member of the prosecutions team, almost all the participants stated ‘Yes’ to Scenario 1 (where the role of perpetrator and victim is intentionally ambiguous), ‘Yes’ to Scenario 2 (where the criminal offence is coercive control), and ‘Yes’ to Scenario 3 (where the IPV incident involves two males in a same-sex relationship and the crime is sexually motivated). However, the sample was split when considering reallocation of the case in Scenario 4 (where the IPV incident involves a cisgender male and a transgender female). The respondents’ perceptions of prosecutorial processes and outcomes regarding LGBTIQ IPV in each of the hypothetical situations are shown in Table 6.

Discussion and conclusion

Using an online survey with hypothetical vignettes depicting IPV situations in the LGBTIQ community, our research explored police prosecutors’ recognition of, and response to, IPV situations involving LGBTIQ people. Our research also examined prosecutors and the likelihood of IPV occurring in LGBTIQ relationships, and whether friendships, (social and professional) interaction, and levels of trust in LGBTIQ people shape their perceptions of LGBTIQ IPV, LGBTIQ perpetrators, and victims. Overall, the results show that police prosecutors in the QPS are unable to clearly distinguish between perpetrators and victims in some LGBTIQ IPV scenarios, particularly where coercive control is involved, or a transgender person is the victim, and as such, are less likely to recognise and then respond appropriately to incidents of IPV involving LGBTIQ people. The results suggest that police prosecutors are unable to clearly distinguish between perpetrators and victims in LGBTIQ IPV scenarios, particularly when an incident of IPV involves cisgender and transgender people. The results also suggest that male and female officers (particularly those aged between 18 and 33 years of age) differ in their recognition of LGBTIQ perpetrators, and struggle to recognise LGBTIQ victims of IPV.

The role of the police prosecutor in police organisations in Australia is to determine whether prosecutorial action will be taken on IPV depending on the nature of the IPV, and the evidence provided. In Queensland, most police charges commenced by the QPS (the police organisation tasked with policing the entire state of Queensland) are prosecuted by internally employed QPS prosecutors in Magistrates Courts, with more serious charges prosecuted by the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP). Under the DFVPA (2012) police are granted power to investigate an incident of IPV, and under the ‘Police Powers and Responsibilities Act 2000’ it is the police prosecutor who determines whether prosecutorial action will be taken depending on the nature of the IPV as well as the type and seriousness of the offence (OPM QPS 2021). When an arrest for an incident of IPV occurs, the role of the QPS police prosecutor is to ensure a brief of evidence is created, to act or appear for the prosecution in the legal proceeding. Essentially, the responsibility to prosecute IPV charges rests with the QPS police prosecutors (OPM QPS 2021).

Yet the results indicated that many of the police prosecutors are unable to recognise and categorise an incident of IPV involving members of the LGBTIQ community in these hypothetical situations, with many officers struggling to recognise LGBTIQ perpetrators and victims. Whilst police prosecutors are highly experienced in recognising and responding to IPV involving heterosexual cisgender perpetrators and victims, the hypothetical situations of IPV involving LGBTIQ people challenged their abilities. Given the lack of recognition that police prosecutors had towards the different types of LGBTIQ IPV, and LGBTIQ perpetrators and victims, it is likely that some of the prosecutors’ responses were affected by the typologies of IPV presented or the type of criminal evidence contained within the scenarios.

Certainly, this may be the case with many of the responses to Scenario 2. Scenario 2 involved examples of coercive control as opposed to instances of physical violence, and whilst that scenario identifies a perpetrator and a victim, most participants indicated that they would not proceed with a prosecution. Whilst coercive control is a criminal offence recognised under the law in England and Wales, and in some other European countries (such as France) at present, coercive control is not criminalised under the existing criminal code in Queensland (Parliament of Australia 2021). Similar to other parts of the globe (such as Canada, the USA) police prosecutors are unable to prosecute perpetrators of coercive control under existing IPV legislation unless there is evidence of a physical injury, damage to a property, sexual abuse, verbal abuse, harassment or intimidation, financial abuse, or evidence of stalking (OPM QPS 2021). Research by Robinson, Myhill, and Wire (2018) also suggests that many police officers are unsure whether coercive control is IPV (unlike traditional IPV offences involving physical violence), because coercive control involves a course of behaviour rather than one specific and clearly injurious incident (Stark 2012). The inclusion of coercive control as an act of IPV within the hypothetical situations certainly raises more questions than answers regarding the police prosecutor’s abilities to recognise different types of IPV.

It was also interesting that many prosecutors were unable to clearly distinguish between the perpetrator and victim in the IPV situation or respond appropriately to IPV involving a cisgender and transgender person. According to research by Miles-Johnson, (2020) and Russell and Sturgeon (2019) many police officers have been criticised for not taking IPV incidents seriously when it involves a transgender person. Many transgender people have reported that investigating officers have blamed that person’s transgender identity for being in some way responsible for the crime, thereby altering who police treat as perpetrator and victim in IPV situations (Decker et al. 2018; Messinger & Roark 2019). This is problematic given that existing criticisms of police responses to IPV have identified significant inadequacies in the way police officers interact with all citizens during such responses (Franklin et al. 2019; HMIC 2014). It is also problematic given that IPV policing practices are linked to traditional notions of heteronormative and cisnormative behaviour and heterosexual sexuality enacted under patriarchal ideals (Miles-Johnson 2020; Natarajan 2016). If police fail to recognise and respond appropriately to IPV involving LGBTIQ people, then such violence is likely to remain hidden and therefore not responded to (Decker et al. 2018; Messinger & Roark 2019).

Some progress has been made in recent years in enhancing the recognition of these issues and improving societal, criminal justice, and policy responses to them (Irlam 2013; Pitts et al. 2006). In Australia, laws relating to IPV are gender-neutral to allow their application to LGBTIQ contexts. The ‘Domestic Family Violence Protection Act’ (DFVPA) (2012) (Queensland Government 2012) even specifies that LGBTIQ people may be particularly vulnerable to IPV. The Act also stipulates that any response to IPV by police involving LGBTIQ people should consider the characteristics of each person, whether perpetrator or victim of IPV (S 5 (d) DFVPA 2012). Moreover, policing services are increasingly working to improve their recognition of, and response to, LGBTIQ IPV. For example, in 2015, QPS instigated the ‘Special Taskforce on Domestic and Family Violence’ and acknowledged that IPV suffered by LGBTIQ members of the community was largely under-reported, under-researched, and that members of the LGBTIQ community frequently described that such violence was either ignored or overlooked by QPS officers.

IPV responses constitute a core part of police work and comprise a considerable proportion of the work that prosecutorial officers undertake within the prosecutions team (OPM QPS 2021). It is vital, therefore, that prosecutorial officers recognise and respond appropriately to cases involving LGBTIQ IPV in context of their work. Since it is the responsibility of the QPS prosecutions team to prosecute IPV charges in Queensland, the inability of officers to recognise IPV situations and or perpetrators or victims of IPV in the LGBTIQ community raises questions about the capacity of the QPS to enhance their officer’s victim profiling skills. If prosecutors are unable to distinguish the unique circumstances that LGBTIQ relationships present in IPV situations, then early identification of vulnerable people and high-risk groups who may be experiencing IPV is considerably more difficult. Critics of police recognition of IPV across much of the globe argue that this is an ongoing issue which police organisations need to overcome if they are to successfully evaluate and respond to incidents of IPV (see Decker et al. 2018; Franklin et al. 2019; Messinger & Roark 2019; Miles-Johnson 2020).

Given that the role of the police prosecutor in Queensland is to determine whether prosecutorial action will be taken, it is concerning that a prosecutor’s inability to distinguish different types of IPV experienced by LGBTIQ people opens the possibility that LGBTIQ people will be treated unfairly in the criminal justice process. The difficulties of recognising and responding to LGBTIQ IPV outlined here also raises questions about the ability of the QPS to develop effective relationships with LGBTIQ community partners to increase trust in police, and subsequently increase the likelihood that IPV (and other crimes) will be reported to the police. Without the formal reporting of IPV, policing organisations cannot fulfil their key role of responding to crime and aiding all citizens during times of crisis (see Decker et al. 2018; Franklin et al. 2019; Messinger & Roark 2019; Miles-Johnson 2020).

One solution to address the problems of recognition and response explored in this study is for police organisations to maintain a culture of continuous improvement in prosecution engagement strategies and to implement adequate ongoing awareness training for prosecutions officers regarding LGBTIQ IPV. Research by Miles-Johnson, (2020) regarding police training and the LGBTIQ community in Australia, however, suggests that specific programmes educating police about the importance of recognition and response to incidents of IPV involving LGBTIQ people are virtually non-existent in Australia. This has also been a problem in other countries such as Canada, and the USA, where officer training programmes regarding recognition of and response to LGBTIQ IPV are non-existent (Saxton et al. 2018). Many police training programmes that do exist are generalised awareness training programmes, which focus on processing LGBTIQ people as they enter the criminal justice system (as perpetrators of crime) and do not focus on specific types of crime or victimisation (Dwyer et al. 2017; Miles-Johnson 2020). They do not train police working across all policing contexts about appropriate engagement strategies with the LGBTIQ community or improve their awareness of the unique needs of these communities (Miles-Johnson et al. 2018). Enhancing LGBTIQ IPV training is vital if the QPS and other police organisations are to achieve the objective of improving policing responses to LGBTIQ victims of IPV and fostering the inclusion of LGBTIQ people in the criminal justice process to enhance public satisfaction during police-citizen engagement (Decker et al. 2018). Enhancing LGBTIQ IPV training could include creating specific training programmes which emphasise officer use of appropriate risk assessment tools and processes to identify and recognise LGBTIQ IPV, as well as training officers to recognise and respond to the different types of victimology LGBTIQ victim-survivors experience during times of IPV. The creation of specific LGBTIQ IPV training programmes may help dispel potential biases officers may have towards members of the LGBTIQ community or lessen heteronormative stereotypes associated with cisgender incidents of IPV.

There are, however, several limitations to this study. First, there are limits to the use of hypothetical vignettes in research since these may not be comparable to data collected in real-life situations (Miles-Johnson et al. 2018). Second, whilst the hypothetical vignettes are based on real-life scenarios recorded by police officers working in the QPS, other victim or perpetrator dimensions not measured in this survey might influence a police prosecutor’s perception of whether an IPV incident has occurred. Third, the study was conducted with only one police organisation in Australia and, as such, further research with other police organisations across Australia could determine if these results are representative of police prosecutors in different police organisations. Despite these limitations, this study provides several important insights regarding police prosecutors’ recognition and response to IPV.

Non recognition of LGBTIQ IPV, and, subsequently, lack of appropriate police response regarding IPV in LGBTIQ relationships has severe implications for police organisations regarding policy and practice, particularly in relation to police organisations being investigated for incidents of poor policing and police misconduct, or differential policing and discriminatory policing practices (Miles-Johnson 2020). Accurately recognising and appropriately responding to IPV situations in the LGBTIQ community is, therefore, vital since no other public-service agency has the capacity to discriminate against LGBTIQ people or shape their access to justice in the same way as police organisations (Morgan et al. 2018). Traditional notions of law enforcement or police engagement used to identify and police heteronormative cisgender incidents of IPV are not appropriate for (or tailored towards) LGBTIQ IPV (Decker et al. 2018; Miles-Johnson 2020). Prior to this study, there has been a lack of knowledge regarding whether police prosecutors are able to appropriately recognise IPV with LGBTIQ people and in LGBTIQ relationships, and how they would interact with or respond to LGBTIQ people during this type of victimisation. Policing research examining prosecutorial practices and responses to LGBTIQ IPV has been lacking and further targeted research examining the prevalence and experience of LGBTIQ people who experience IPV and then progress through the legal system is needed. For officers involved in the prosecutorial process, for police organisations to respond appropriately to LGBTIQ IPV situations, and for LGBTIQ people to experience greater justice in the criminal justice context, recognition of LGBTIQ IPV, perpetrators, and victims by police needs to improve.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Queensland University of Technology Approved Human Research—Negligible-Low Risk 1,900,000,666.

Queensland University of Technology Approved Human Research—Negligible-Low Risk 1,900,000,666.

There is much debate regarding how best to situate sexuality and gender diversity, particularly regarding the benefits and disadvantages of drawing together issues relating to sexuality, gender, and intersex status under the homogenous umbrella of LGBTIQ (see Ghaziani 2011).

After consultation with senior Aboriginal police officers working in the QPS, it was decided that the terms ‘Aboriginal’ and ‘Torres Strait Islander’ would be used as separate identifiers, thereby allowing police officers from each group to distinguish their identity.

References

Alliance for a Safe & Diverse DC (2008) Move along: policing sex work in Washington, DC: a report by the Alliance for a Safe & Diverse DC. Different Avenues, Washington, DC

Barnes R (2013) ‘She expected her women to be pretty, subservient, dinner on the table at six’: problematising the narrative of egalitarianism in lesbian relationships through accounts of woman-to-woman partner abuse. In: Sanger T, Taylor Y (eds) Mapping intimacies: relations, exchanges, affects. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, pp 130–149

Berman A, Robinson S (2010) Speaking out: stopping homophobic and transphobic abuse in Queensland. Australian Academic Press, Brisbane

Brick J.M., & Kalton, G. (1006). Handling missing data in survey research. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 5(3), 215–238.

Broderick E (2011) Not so straight forward: domestic violence in Australia. Altern Law J 36(4):224

Buzawa ES, Buzawa CG (2017) Global responses to domestic violence. Springer, Cham

Canales M (2000) Othering: toward an understanding of difference. Adv Nurs Sci 22:16–31

Carrington C (1999) No place like home: Relationships and family life among lesbians and gay men. University of Chicago Press, London

Decker M, Littleton HL, Edwards KM (2018) An updated review of the literature on LGBTQ+ intimate partner violence. Curr Sex Health Rep 10(4):265–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-018-0173-2

Donovan C, Barnes R (2020) Barriers to recognising domestic violence and abuse: power, resistance and the re-storying of ‘Mutual Abuse’. In: Queering narratives of domestic violence and abuse. Palgrave studies in victims and victimology. Palgrave Pivot, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35403-9_4

Dwyer AE, Ball MJ, Bond C, Lee M, Crofts T (2017) Reporting victimisation to LGBTI (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex) police liaison services: A mixed methods study across two Australian states (Report to the Criminology Research Advisory Council Grant: CRG 31/11-12). Criminology Research Advisory Council.

Edelman EA (2014) “Walking while transgender”: Necropolitical regulations of trans feminine bodies of colour in the nation’s capital. In: Haritaworn J, Kuntsman A, Posocco S (eds) Queer necropolitics. Routledge, London, pp 172–190

Erfanian F, Roudsari RL, Heydari A, Bahmani MND (2020) A narrative on using vignettes: its advantages and drawbacks. J Midwif Reprod Health 8(2):2134–2145

Finneran C, Stephenson R (2012) Intimate partner violence among men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 14(2):168–185

Franklin CA, Goodson A, Garza AD (2019) Intimate partner violence among sexual minorities: predicting police officer arrest decisions. Crim Justice Behav 46:1181–1199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854819834722

Gerstner D (2018) Predictive policing in the context of residential burglary: an empirical illustration on the basis of a pilot project in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Eur J Secur Res 3:115–138

Ghaziani A (2011) Post-Gay Collective Identity Construction. Soc Probl 58(1):99–125

Hacker RL, Horan JL (2019) Policing people with mental illness: experimental evaluation of online training to de-escalate mental health crises. J Exp Criminol 15:551–567

Heidenreich L (2011) Transgender women, sexual violence, and the rule of law: an argument in favor of restorative and transformative justice. In: Lawston JM, Lucas AE (eds) Razor wire women: prisoners, activists, scholars, and artists. State University of New York Press, Albany, NY, pp 147–164

Hughes R, Huby M (2004) The construction and interpretation of vignettes in social research. Soc Work Soc Sci Rev 11(1):36–51

HMIC (2014) Everyone’s business: improving the police response to domestic abuse. Retrieved from https://www.hmic.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/improving-the-police-response-to-domestic-abuse.pdf

Irlam C (2013) Discussion Paper. LGBTI data: developing an evidence-informed environment for LGBTI health policy. National LGBTI Health Alliance, Sydney

Langenderfer-Magruder L, Whittlefield DL, Walls NE, Kattari SK, Ramos D (2016) Experiences of intimate partner violence and subsequent police reporting among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer adults in Colorado: comparing rates of cisgender and trans- gender victimization. J Interpers Violence 31:855–871. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626051455676

Lewandowski C, Carter JG, Campbell WL (2018) The utility of fusion centres to enhance intelligence-led policing: an exploration of end-users. Policing 12(2):177–193

Mbuba J (2021) Global perspectives in policing and law enforcement. The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group Inc, United Kingdom

Messinger AM, Roark J (2019) Transgender intimate partner violence and aging. In: Hardacker C, Ducheny K, Houlberg M (eds) Transgender and gender nonconforming health and aging. Springer, Cham, pp 79–95

Miles-Johnson T (2021) Comparative Perceptions: how female officers in two Australian police organizations view policing of diverse people. Police Pract Res Int J 22(3):1294–1313

Miles-Johnson T (2020) Policing transgender people and intimate partner violence (IPV). In: Russell B (ed) Gender and sexual orientation: understanding power dynamics in intimate partner violence. Springer, Cham

Miles-Johnson T, Mazerolle L, Pickering S, Smith P (2018) Perceptions of prejudice: police awareness training and prejudiced motivated crime. Policing Soc 28(6):730–745. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2016.1206099

Morgan A, Boxall H, Brown R (2018) Targeting repeat domestic violence: assessing short-term risk of reoffending. Trends and issues in crime and criminal justice No. 552. Australian Institute of Criminology.

O’Dell L, Crafter S, de Abreu G, Cline T (2012) The problem of interpretation in vignette methodology in research with young people. Qual Res 12(6):702–771

Ovenden G, Salter M, Ullman J, Denson N, Robinson K, Noonan K, Bansel P, Huppatz K (2019) Gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer men’s attitudes and experiences of intimate partner violence and sexual assault. In: Sexualities and genders research. Western Sydney University and ACON.

Parliament of Australia (2021) The House Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs—Inquiry into Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House/Social_Policy_and_Legal_Affairs/Familyviolence/Report

Pickles J (2019) Policing hate and bridging communities: a qualitative evaluation of relations between LGBT+ people and the police within the North East of England. Policing Soc 30(7):741–759

Pitts M, Smith A, Mitchell A, Patel S (2006) Private lives: a report on the health and wellbeing of GLBTI Australians. Monograph Series No. 57. Melbourne, Victoria: La Trobe University, The Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society

Queensland Government. (2012). Domestic Family Violence Protection Act (DFVPA) 2012. Accessed online: https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/pdf/2017-05-30/act-2012-005

Queensland Police Service (QPS) (2021) Operational Procedures Manual Issue 83, Public Edition—Effective 30th July 2021. Accessed online https://www.police.qld.gov.au/qps-corporate-documents/operational-policies/operational-procedures-manual

Redfern JS (2014) Best practices to improve police relations with transgender individuals. J Law Enforc 3(4):1–17

Robinson AL, Myhill A, Wire J (2017) Practitioner (mis)understandings of coercive control in England and Wales. Criminol Crim Just 18(1):29–49

Russell B, Sturgeon JA (2019) Police evaluations of intimate partner violence in heterosexual and same-sex relationships: do experience and training play a role? J Police Crim Psychol 34(1):34–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-018-9279-8

Santos RG (2018) Police organizational change after implementing crime analysis and evidence-based strategies through stratified policing. Policing 12(3):288–302

Saxton MD, Olszowy L, MacGregor JCD, MacQuarrie BJ, Wathen CN (2018) Experiences of intimate partner violence victims with police and the justice system in Canada. J Interpers Violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518758330

Stark E (2012) Looking beyond domestic violence: policing coercive control. J Police Crisis Negot 12(2):199–217

Whitton SW, Newcomb ME, Messinger AM, Byck G, Mustanski B (2016) A longitudinal study of IPV victimization among sexual minority youth. J Interpers Violence 34(5):912–945. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516646093

Wolff KB, Cokely CL (2007) “To protect and to serve?”: An exploration of police conduct in relation to the gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender community. Sex Cult 11(2):1–23

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Ethical approval

Queensland University of Technology, (QUT), Approved Human Research—Negligible-Low Risk #1900000666.

Consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miles-Johnson, T., Ball, M. Police prosecutors and LGBTIQ intimate partner violence, victims, and perpetrators: an empirical study. SN Soc Sci 2, 84 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00382-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00382-z