Abstract

We contribute to the recent debates on demand and growth regimes in modern finance-dominated capitalism linking them to the post-Keynesian research on macroeconomic policy regimes. We examine the demand and growth regimes, as well as the macroeconomic policy regimes for the big four Eurozone countries, France, Germany, Italy and Spain, for the periods 2001–2009 and 2010–2019. First, our approach supports the usefulness of the identification of demand and growth regimes according to growth contributions of the main demand components and financial balances of the macroeconomic sectors. This allows for an understanding of the demand sources of growth, or stagnation, if there is a lack of demand, of how these sources are financed and of potential financial instabilities and fragilities. Second, when it comes to the macroeconomic policy drivers of demand and growth regimes, as well as their respective changes, we show that the exclusive focus on fiscal policies, as in the previous literature, is too limited and that it is the macroeconomic policy regime which matters here, i.e. the combination of monetary, fiscal and wage policies, as well as the open economy conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Post-Keynesian research on the macroeconomics of financialisation, or on finance-dominated capitalism, has generated the notion of ‘demand and growth regimes under financialisation’. This was meant to distinguish between different ways countries cope with the depressive macroeconomic effects of financialisation, the regressive re-distribution of income, with negative effects on income-financed consumption, and depressed investment in the real capital stock caused by shareholder value orientation of management of non-financial corporations, in particular (Hein 2012; Stockhammer 2015). The two extreme and opposed regimes that have been derived were the ‘debt-led private demand boom’ regime and the ‘export-led mercantilist regime’. The former relies on debt-financed private (consumption) demand as the main source of demand and growth, whereas the latter relies on foreign demand and leads to rising indebtedness of the foreign sectors (Hein 2019). This distinction of regimes should not be confused with the more basic distinction between wage- and profit-led demand and growth regimes in the post-Keynesian/Kaleckian distribution and growth literature, with a more basic focus on the effects of changes in functional income distribution on aggregate demand and growth (Hein 2014, chapters 6–7). This latter approach does not imply that in a wage-led demand and growth regime necessarily pro-labour distribution policies are applied or that in profit-led demand and growth regime pro-capital policies will dominate (Lavoie and Stockhammer 2013). Therefore, certain countries may be wage-led in this basic sense and may then be dominated by either a debt-led private demand boom regime or an export-led mercantilist regime, in order to cope with the depressive demand and growth effects imposed by redistribution at the expense of labour.

Recently, the post-Keynesian/Kaleckian demand and growth regime approaches have resonated in the comparative political economy (CPE) literature (Baccaro and Pontusson 2016, 2018; Hope and Soskice 2016; Piore 2016; Streeck 2016). Post-Keynesians have also provided attempts at linking their demand and growth regime approach to the CPE literature on institutional varieties or welfare state models in modern capitalism (Behringer and van Treeck 2017; Hein et al. 2020; Setterfield and Kim 2020; Stockhammer 2021; Stockhammer and Ali 2018).

Furthermore, a couple of years after the Great Financial Crisis and the Great Recession of 2007–2009, as a result of the contradictory nature of finance-dominated capitalism, several post-Keynesians have started to analyse the shifts of demand and growth regimes. As argued in particular by Hein (2019), Hein et al. (2020) and Hein and Martschin (2020), the type of shift of the previous debt-led private demand boom economies has depended on the requirement of private sector deleveraging after the financial crisis as well as on the ability and willingness to run deficit-financed and stabilising fiscal policies. The institutional constraints imposed on national fiscal policies in the Eurozone member countries, the absence of relevant fiscal policies at the Eurozone level and the turn towards austerity policies when the Eurozone crisis started in 2010, therefore, explain to a large extent, why in particular European debt-led private demand boom countries turned export-led mercantilist (or weakly export-led) after the Great Financial Crisis and the Great Recession (Hein and Martschin 2020). Those debt-led private demand boom countries before the crisis, which were able to make use of expansionary deficit-financed fiscal policies, in particular the UK and the USA, however, compensated private deleveraging by rising public deficits, thus stabilising aggregate demand in their countries and turning to a domestic demand-led regime stabilised by public deficits (Hein 2019).

Kohler and Stockhammer (2021) have recently provided a more systematic cross-country analysis of the underlying growth drivers before and after the 2007–2009 crises in 30 OECD countries. They consider the requirements of deleveraging in the context of a financial boom-bust cycle, the role of fiscal policies and the relevance of price and non-price competitiveness for exports in order to explain the emergence of the different post-crisis regimes. They find that the former two drivers have had a major role to play, whereas differences and changes in international price competitiveness have been overrated in some of the previous CPE literature on macroeconomic regimes. Furthermore, they abandon the regime distinction, which has been developed for the pre-crisis period, and rather focus on the distinction of the different growth drivers for the clustering of countries in the post-crisis period.

We consider the focus on underlying growth drivers an important step forward and attempt to contribute to this line of research. However, we will not completely give up the pre-crisis regime typology but rather link it with the post-Keynesian notion of macroeconomic policy regimes, which has been developed and frequently applied in the early 2000s (i.e. Fritsche et al. 2005; Hein and Truger 2005; Herr and Kazandziska 2011). Here the focus is not only on fiscal policies, as in Kohler and Stockhammer (2021), but on the complete macroeconomic policy mix of monetary, wage and fiscal policies, as well as their interactions, considering also the open economy conditions for the respective country. This approach is based on post-Keynesian macroeconomics in general and the requirement of coordinated macroeconomic policies derived from this approach in particular (Arestis 2013; Hein and Stockhammer 2010). Applying this approach in a standardised way using the same sets of indicators for the big four Eurozone countries, France, Germany, Italy and Spain, should shed some more light on the economic policy drivers of the respective demand and growth regimes, which have led to the 2007–2009 crises, and the regime shift thereafter.

The focus on the broader macroeconomic policy regime and its several indicators, instead of just one fiscal policy indicator, comes at a cost. In order to keep the data analysis tractable and focus on our contribution, we do not link our analysis back to the financial systems and institutions in the four countries, which are important for the possibilities of debt-financed expansion, collapse and contraction. We are aware of this limitation and leave a systematic indicator-based analysis for future research. Here we will only refer to country case studies on our countries by others, who have analysed the different degrees and types of financialisation and the 2007–2009 crises in these countries, as background for our research.

The selection of countries for our study was guided by the requirement to have examples for each pre- and post-crisis types of demand and growth regime discovered in the studies referred to above in our analysis. Furthermore, focussing on Eurozone countries contributes to the understanding of the imbalances before and after the 2007–2009 crises within the Eurozone, which have been associated with the different demand and growth regimes. For our analysis, we will distinguish two periods, the first period from 2001–2009 which includes the Great Financial Crisis and the Great Recession, and a second period from 2010–2019 which includes the Eurozone crisis starting in 2010 and the Eurozone recession in 2012/2013. In particular, for the latter period, a detailed analysis of the macroeconomic policy regime should add to our understanding of growth drivers and regime changes.

Our analysis proceeds as follows. In Sect. 2, we will recap the concept of demand and growth regimes in finance-dominated capitalism and apply a standardised set of indicators to our four countries in order to derive the demand and growth regimes for the two periods. In Sect. 3, we will present the post-Keynesian macroeconomic policy regime approach, based on post-Keynesian macroeconomics, and the requirement of coordinated macroeconomic policies, which should be conducive to a stable domestic demand-led growth regime. We will also present the set of indicators, which we will then apply to our four countries in Sect. 4 for the two periods. In the latter section, we will further derive the linkages between demand and growth regimes and macroeconomic policy regimes and explain how the latter has affected the former. Section 5 will sum up and conclude.

2 Demand and growth regimes in finance-dominated capitalism and the shift of regimes

2.1 The concept of demand and growth regimes in finance-dominated capitalism

The Kaleckian/post-Keynesian concept of macroeconomic demand and growth regimes used in this paper focuses on the period of financialisation of modern capitalism or of finance-dominated capitalism. In this period, since the late 1970s/early 1980s starting in the USA and the UK, the capitalist economies have been exposed to the liberalisation of financial markets, the development of new financial instruments and an overall increasing role of finance in the operation of the economies, to different degrees in different countries (Epstein 2005). From a macroeconomic perspective, this has had important implications for (1) income distribution, (2) investment in capital stock, (3) consumption and (4) the build-up of global and regional (European) current account imbalances (Hein 2012).Footnote 1

With respect to income distribution, financialisation has been associated with increasing profit shares, higher top income shares and rising inequality of household incomes.Footnote 2 Moreover, financialisation has coincided with lower investment in capital stock. This trend emerged as shareholder power vis-à-vis firms and workers increased, shifting firms’ objectives from long-run growth to short-term profitability through financial activities.Footnote 3 These first two features of financialisation have negatively affected aggregate demand—both directly by decreasing investment and indirectly by re-distributing income to groups with lower propensities to consume in mostly wage-led economies.Footnote 4 In some countries, this shortfall in aggregate demand was compensated by wealth-based and debt-financed consumption, which was facilitated by the liberalisation of the financial sector. Other countries facing rising income inequality and dampened real investment were relying on net exports to stabilise aggregate demand.Footnote 5 These two different growth models have been mirrored by opposed but complementary external account positions of the two country groups. The current account deficits of the debt-financed model have been matched by the current account surpluses of the export-led model. Financialisation contributed to these developments to the extent that the deregulation and liberalisation of international capital markets and capital accounts have allowed current account imbalances to persist and deficits to be financed over longer periods (Hein 2012, chapter 6; Stockhammer 2015).

In what follows, we will assess the demand and growth regimes of the big four Eurozone countries, France, Germany, Italy and Spain, as well as the initial core Eurozone (EA-12). This follows a procedure initially introduced by Hein (2011), which has since been used in several studies with some variation in the labelling of regimes for the period leading to the Great Financial Crisis and the Great Recession (2007–2009) and for the shift of regimes during and after these crises.Footnote 6

First, we will look at the growth contributions of the main demand aggregates, private and public consumption, investment, exports and imports, i.e. net exports, which should sum up to real GDP growth. Second, we will examine the sectoral financial balances of the main macroeconomic sectors, the private household sector, the financial and non-financial corporate sectors, the government sector and the external sector, which should sum up to zero. Together, this allows for an understanding of the demand sources of growth, or stagnation, if there is a lack of demand and hence no or little growth, of how these sources are financed, and of potential financial instabilities and fragilities. It allows to distinguish different demands and growth regimes and to cluster countries accordingly. These two sets of indicators will thus allow us to distinguish between (1) a debt-led private demand boom regime, (2) an export-led mercantilist regime, (3) a weakly export-led regime and (4) a domestic demand-led regime:

The debt-led private demand boom regime is characterised by deficits of the private domestic sectors as a whole, which are, on the one hand, driven by corporate deficits and, on the other hand, by negative or close to zero financial balances of the private household sectors. The latter implies that major parts of the private household sector have negative saving rates out of current income and finance these deficits by increasing their stock of debt or by decreasing their stock of assets. The deficits of the (private) domestic sectors are mirrored by positive financial balances of the external sector, i.e. current account deficits. Demand growth is mainly led by private domestic demand, to a large degree financed by credit, while the balance of goods and services negatively contributes to growth.

The export-led mercantilist regime shows positive financial balances of the domestic sectors as a whole, and by the private household sector in particular, that are matched by negative financial balances of the external sector, indicating current account surpluses. There are relevant growth contributions of the positive balance of goods and services, and thus, rising net exports and current account surpluses, and small or even negative growth contributions of domestic demand.

The weakly export-led regime shows either positive financial balances of the domestic sectors or negative financial balances of the external sector, and hence current account surpluses, but negative growth contributions of the balance of goods and services, and thus falling net exports and current account surpluses. Alternatively, we may have negative financial balances of the domestic sectors, positive financial balances of the external sector and hence current account deficits, but positive growth contributions of the balance of goods and services, and thus improving net exports and falling current account deficits.

The domestic demand-led regime is characterised by positive financial balances of the private household sector, while the government and, to some extent, the corporate sector are running deficits. After the crisis, in particular, the government sector has been the deficit sector in several countries following this regime. The external sector is roughly balanced with only small deficits or surpluses. Domestic demand contributes positively to demand growth (without relying on private household deficits) and there are slightly negative or positive growth contributions of the balance of goods and services.

Our analysis for the four Eurozone countries and the historical core Eurozone as a whole, the EA-12, will distinguish average values over two periods: first, the period from 2001 until 2009,Footnote 7 thus including the Great Recession, and second, the period from 2010 until 2019 which includes the Eurozone Crisis starting in 2010. This periodisation allows us to focus on the changes in macroeconomic policy regimes associated with the Eurozone crisis and their effects on the changes in demand and growth regimes, in particular.

2.2 Demand and growth regimes before and after the 2007–2009 crisis Footnote 8

Between 2001 and 2009, Spain was characterised by the debt-led private demand boom regime, with negative financial balances of the private domestic sector as a whole, mainly consisting of high deficits of the private household sector (Table 1). The counterpart to the negative financial balances of the domestic sectors was the positive financial balance of the external sector, indicating current account deficits. The debt-led private demand boom country showed the highest real GDP growth rate compared to France, Germany and Italy, with a real GDP growth rate well above EA-12 average. Growth was led by domestic demand, in particular by private consumption, financed by financial deficits of private households to a large degree. The balance of goods and services contributed negatively to GDP growth in Spain, indicating falling net exports and rising current account deficits.

In the period 2001–2009, Germany was dominated by the export-led mercantilist regime, being characterised by negative financial balances of the external sector and, hence, by current account surpluses (Table 1). These deficits were mirrored by positive financial balances of the domestic sectors as a whole, with considerable surpluses of the private sector. Compared to the other economies, Germany displayed a moderate and considerably below EA-12 average real GDP growth rate, which was almost exclusively driven by net exports, with a close to zero growth contribution of domestic demand.

France and Italy, as well as the EA-12 as a whole, can be classified as domestic demand-led regimes on average over the period 2001–2009 (Table 1). They were characterised by positive financial balances of the private household sectors, while the public sectors—and also the corporate sector in Italy—were running deficits. The external sectors showed slight deficits for France and the EA-12, and small surpluses for Italy. Growth rates were modest for France and the EA-12, while Italy was hardly growing and virtually stagnating, mainly driven by domestic demand with slightly positive (EA-12) or negative (Italy, France) growth contributions of the balance of goods and services.

The emergence of the two extreme macroeconomic growth regimes under financialisation before the crisis, the debt-led private demand boom regime, represented by Spain in our study, and the export-led mercantilist regime, represented by Germany, implied large current account imbalances at the global and Eurozone level, as shown in Fig. 1 (see also Hein 2012, chapters 6 and 8, 2019). These imbalances were driven by high growth contributions of private domestic demand, fuelled in particular by the increasing indebtedness of the private household sector in debt-led private demand boom countries that also provided expanding markets for the export-led mercantilist economies. When the Great Financial Crisis and then the Great Recession hit in 2007–2009—first in the USA and then in the European debt-led private demand boom countries—these crises were quickly transmitted to the export-led mercantilist economies and also to the domestic demand-led economies, through the international trade and the financial contagion channels.

Current account balance in core Eurozone countries, 2001–2019 (in bn euros). Source: European Commission (2019), authors’ representation

Initially, expansionary fiscal policy measures were applied, also in the Eurozone, as we will analyse in more detail in Sect. 4 for our four countries. But when the crisis turned into the Eurozone Crisis in 2010, which mainly affected the periphery, the Eurozone responded by turning towards austerity policies. The necessary financial rescue packages for the concerned countries, as well as a gradual extension of the role of the European Central Bank (ECB) towards a guarantor of government debt of Eurozone member countries, were linked to the enforcement of ‘structural reforms’ in the labour market and fiscal austerity policies (De Grauwe 2012; Dodig and Herr 2015; Hein 2013/14).Footnote 9 The latter contributed to another recession in the EA-12 in 2012/2013 and to a weak recovery in international comparison (Fig. 2). EA-12 growth has been lagging behind the USA, for which the recovery has also been weak from historical perspective.Footnote 10 Furthermore, the weak recovery of the EA-12 has been highly asymmetric, with Germany growing at a rate well above average, France at a roughly average rate, and the crisis countries in the periphery below average (Spain slightly and Italy considerably) (Fig. 2).

Real GDP in Spain, Germany, France, Italy, the EA-12, and the USA, 2007–2019, 2007 = 100. Source: European Commission (2019), authors' representation

The period 2010–2019 has seen a considerable shift in demand and growth regimes. The former debt-led private demand boom country Spain has turned towards the export-led mercantilist regime. Spain significantly improved its current account, such that from 2012 on and on average over the period 2010–2019, Spain saw negative financial balances of the external sector (Table 1, Fig. 3). The reduction of the external deficit was accompanied by a substantial deleveraging of the private sectors, whose financial balances turned positive after 2009, associated with dampened private consumption and investment demand. While public sector deficits stabilised the economy up to 2012, austerity measures implemented in response to the Eurozone Crisis then forced Spain to decrease its public deficit considerably, leading to a constant reduction of public deficits until 2019. On average over the period 2010–2019, however, the public financial balances remained deeply negative. Growth contributions of domestic demand collapsed, and weak growth was mainly driven by the balance of goods and services. Interestingly, the improved growth contributions of net exports were caused by improved exports, and not by declining imports.

Spain—sectoral financial balances as a percentage share of nominal GDP, 2001–2019. Source: European Commission (2019), authors’ calculations and representation

The initially export-led mercantilist economy of Germany remained so in the period 2010–2019. The financial deficit of its external sector, hence current account surpluses, even increased constantly over the period. Private sector surpluses rose and the government sector consolidated its deficit and even moved towards financial surpluses after 2013/2014 (Table 1, Fig. 4). Germany recovered relatively quickly from the 2007–2009 crisis, initially benefiting from the recovery of the world economy through the external trade channel, and achieved above-average EA-12 growth over the period 2010–2019. Growth contributions of net exports remained considerable but slightly decreased due to increased relevance of (negative) import growth contributions. Growth contributions of domestic demand increased significantly, however, without changing the overall export-led mercantilist nature of the regime.

Germany—sectoral financial balances as a percentage share of nominal GDP, 2001–2019. Source: European Commission (2019), authors’ calculations and representation

France, a domestic demand-led economy in the period 2001–2009, remained so also in the period 2010–2019. With slightly positive external sector financial balances and financial surpluses of the private (household) sector, increasing negative financial balances of the public sector stabilised the domestic demand-led regime in the second period (Table 1, Fig. 5). In the 2007–2009 crisis, high public deficits contributed to the quick recovery of the economy so that France showed EA-12 average growth in the 2010–2019 period. Growth continued to be mainly driven by domestic demand with small negative growth contributions of the balance of goods and services.

France—sectoral financial balances as a percentage share of nominal GDP, 2001–2019. Source: European Commission (2019), authors’ calculations and representation

The other former domestic demand-led economy Italy turned export-led mercantilist in the period 2010–2019. The country generated high private-sector financial surpluses, particularly in the corporate sector, indicating weak investment (Table 1, Fig. 6). The public sector exerted its stabilising function by accepting higher deficits only until 2009, when the public deficit started shrinking. The foreign sector balances decreased significantly after 2010, turning negative on average over the period, such that Italy has seen positive current account surpluses since 2013. Overall, Italy continued to stagnate and witnessed well below EA-12 average growth in the period 2010–2019, which was mainly driven by the balance of goods and services, and here in particular by improved export contributions. Growth contributions of domestic demand turned negative.

Italy—sectoral financial balances as a percentage share of nominal GDP, 2001–2019. Source: European Commission (2019), authors’ calculations and representation

Summing up, we have seen a shift towards the export-led mercantilist regime in Spain and Italy associated with weak growth, joining Germany with higher growth in this group, whereas France has maintained its domestic demand-led regime in the post-2007–2009 period, relying on high government deficits, in particular. Given the size of these major European economies, this has also meant that the regime of the EA-12 as a whole has moved from domestic demand-led towards export-led mercantilist (Table 1). Financial balances of the external sector have turned negative, financial balances of the public sector were still negative on average over 2010–2019, but with a tendency to be balanced, and the private sector, both household and corporate, generated high surpluses. Growth was driven to a considerable extent by net exports, with the increase in export contributions being the main contributor.

This shift towards export-led mercantilism and the ‘rebalancing à la Eurozone’ has not been limited to the major Eurozone economies analysed here, as can be seen in Fig. 1. Whereas the current account of the EA-12 as a whole had been roughly balanced before the start of the Eurozone crisis, most of the EA-12 countries have been running current account surpluses during recent years. As a result, internal current account imbalances have now been externalised, making the core Eurozone, one of the largest economic and monetary areas in the world, a free rider of aggregate demand generated in the rest of the world. On the one hand, this lack of internal demand generation has produced stagnation tendencies in the developed capitalist world as a whole. On the other hand, this export-led mercantilist regime has contributed to global imbalances and the related tendencies towards over-indebtedness in those economies providing the counterpart current account deficits.Footnote 11 This is a problem in particular for those countries that are unable to finance these deficits by issuing debt in their own currencies, in particular the relatively faster-growing emerging market economies. For countries that are able to go into debt in their own currency, the current account deficits may nonetheless face political limits. The turn towards an export-led mercantilist regime has thus not only been harmful to the EA-12 since it has meant weak recovery after the crises 2007–2009, low growth and the associated unemployment problems, in particular in the Eurozone periphery. It also faces serious external risks related to the implied global imbalances. In the following sections, we will turn to the role of the macroeconomic policy regime for this change in demand and growth regimes.

3 The concept of macroeconomic policy regime

The concept of a ‘macroeconomic policy regime’ has been used by some post-Keynesians, as will be referred to below, in order to assess international and intertemporal comparative differences in macroeconomic performances of countries or regions. It describes the set of monetary, fiscal and wage or income policies, as well as their coordination and interaction, against the institutional background of a specific economy, including the degree of openness or the exchange rate regime. Of course, this concept supposes that macroeconomic policies have not only short-run but also long-run effects on macroeconomic performance, i.e. on output, income, employment, inflation, distribution and growth. These effects can be derived from post-Keynesian macroeconomic models generating and considering a full macroeconomic policy mix (i.e. Arestis 2013; Hein and Stockhammer 2010),Footnote 12 as an alternative to the policy mix implied by orthodox New Consensus Macroeconomics (NCM).

The NCM approach has been the macroeconomic backbone of much of the CPE regime research, in particular the varieties of capitalism approach (i.e. Carlin and Soskice 2009, 2015; Hall and Soskice 2001; Hope and Soskice 2016). In the NCM, inflation-targeting monetary policy by central banks is recommended as the main stabilising economic policy tool. Applying the interest rate tool has short-run real effects on unemployment, but in the long run, only the inflation rate is affected. Fiscal policies are to support inflation-targeting monetary policies by balancing the public budget over the cycle. The labour market, together with the social security system, determines equilibrium unemployment, the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU), in the long run, and the speed of adjustment towards this rate in the short run. Since, at least in the long run, there is a clear division of labour between the different areas of economic policy-making, coordination is not required—each area of policy-making would have to follow its tasks as outlined.

The macroeconomic policy regime based on post-Keynesian models acknowledges the need for coordination of economic policies between the different areas, in both the short and the long run, because there is no clear-cut assignment of policy-makers and their instruments to economic policy targets.Footnote 13 According to this perspective, central bank interest rate policies have real effects, in both the short and the long run, on distribution and economic activity. Monetary policy conducive to employment and growth and to a stable domestic demand-led regime should target a nominal long-term interest rate (i) slightly above the rate of inflation (\(\widehat{\mathrm{p}}\)) but below nominal GDP growth (\({\widehat{\mathrm{Y}}}^{\mathrm{n}}\)) or a slightly positive real rate of interest (\(\mathrm{r}=\mathrm{i}-\widehat{\mathrm{p}}\)) below real GDP growth (\(\widehat{\mathrm{Y}}\)):

This condition ensures that real financial wealth is protected against inflation, but that redistribution of income in favour of the productive sector (retained profits of firms and wages of workers) will foster investment in the capital stock, aggregate demand and employment. As we will show below for the government, keeping the interest rate below GDP growth (either in nominal or real terms) makes sure that the deficit sector does not have to run primary surpluses in order to service the debt. Furthermore, the central bank should continue to assume the role of a ‘lender of last resort' during liquidity crises and should continue to stabilise financial markets using tools other than the short-term interest rate. These include the definition of credit standards for refinancing operations with commercial banks, the implementation of reserve requirements for different types of assets, and even reconsider credit controls in order to channel credit into desirable areas and to avoid credit-financed bubbles in certain markets. Most importantly, the central bank should not only act as a lender of last resort for the banking system, but also unconditionally guarantee public debt to allow governments to fulfil their role as a real stabiliser in a way to be explained below, something which is not yet fully given in the Eurozone.

Wage and income policies should accept responsibility for nominal stabilisation, that is for stable inflation rates, in the first place, in particular when full employment is reached, but may also affect income distribution. As an orientation, nominal wages (w) should rise according to the sum of long-run average growth of labour productivity (\(\widehat{\mathrm{y}}\)) in the national economy plus the target rate of inflation for the Eurozone as a whole (\({\widehat{\mathrm{p}}}^{\mathrm{T}}\)) so that unit labour costs (ulc = w/y) grow at the target rate of inflation:

This would allow inflation to reach the target rate, provided that mark-ups in firms’ pricing remain constant, to stabilise income distribution and thus to contribute to a stable domestic demand-led growth regime. In the case of actual inflation rates below the target, such a wage norm would also raise the labour income share during the adjustment process, because the pass through of unit wage costs to prices is usually not perfect. In a wage-led economy, this would then stimulate domestic demand and employment.

At the centre of a post-Keynesian macroeconomic policy regime supporting a stable domestic demand-led growth regime is fiscal policy. Fiscal policy has a major role in stabilising demand at non-inflationary full-employment levels of economic activity and also in a more equal distribution of disposable income in the short and in the long run, which itself is conducive to a stable domestic demand-led regime. Furthermore, fiscal policies can also contribute to improving productivity growth and thus potential growth in the long run, in particular through public education, R&D and investment expenditures. Given the national income accounting identity, according to which the sum of the sectoral financial balances have to sum up to zero, it is clear that the excess of private saving over private investment (S-I), i.e. the private sector financial balance, is always equal to the sum of the current account surplus (X-M), or the negative external sector balance, plus the government deficit (G-T), i.e. the negative government financial balance:

with Sfor private saving, Ifor private investment, X for revenues from exports of goods and factor services, M for payments for the imports of goods and factor services, G for government expenditures, and T for taxes. Therefore, government deficits (D = G − T) have to permanently take up the excess of private saving over private investment, corrected for the current account balances (X-M), which should be close to zero in a domestic demand-led regime, in order to maintain the desired level of economic activity and employment in such a regime.Footnote 14 Apart from this permanent role of government deficits and debt, which also supplies a safe haven for private saving and thus stabilises financial markets, counter-cyclical fiscal policies—together with automatic stabilisers—can stabilise the economy in the face of aggregate demand shocks. From these considerations, we get the following requirements for fiscal policies to stabilise output at some targeted full-employment level:

where DL is the permanent government deficit (or surplus), which is required to keep output at some non-inflationary full employment target (YT) in the long run, and DS is the reaction parameter in the case of short-run deviations of output from target. Fiscal policies can thus also prevent inflationary pressures generated by demand exceeding full-employment levels. Furthermore, governments can also apply progressive income taxes and relevant wealth, property and inheritance taxes, as well as social transfers, which aim at the redistribution of income and wealth in favour of low income and low wealth households. On the one hand, this will reduce the excess of private saving over private investment at non-inflationary full-employment levels (Eq. (3)) and thus stabilise domestic demand. On the other hand, redistributive taxes and social policies will improve automatic stabilisers and thus reduce fluctuations in economic activity and the requirements for short-run discretionary fiscal policies.

As shown by Domar (1944), permanent government deficits will not lead to the explosion of public debt-nominal GDP ratios. With a long-run constant government deficit-nominal GDP ratio (D/Yn), the government debt-nominal GDP ratio (B/Yn) will converge towards a constant value, in the long run, given by the ratio of the deficit-GDP ratio and nominal GDP growth (\({\widehat{\mathrm{Y}}}^{\mathrm{n}}\)):

Furthermore, if we break down the government deficit in a primary deficit (D’) and government interest payments on the stock of debt (iB), Eq. (6) turns to:

Therefore, nominal interest rates below nominal GDP growth will even make a primary deficit consistent with a long-run constant government debt-nominal GDP ratio. It will thus prevent government debt services from redistributing income from the average taxpayer to the rich government bondholders, which would be detrimental to domestic demand. Government deficit spending will thus need the cooperation of the central bank, guaranteeing government debt and keeping interest rates below GDP growth, as argued above.

Against this theoretical background, several post-Keynesian authors have analysed macroeconomic policy regimes for advanced and also emerging capitalist economies. Fritsche et al. (2005) and Herr and Kazandziska (2011) have provided case studies for some advanced economies, looking at several indicators for monetary, fiscal and wage policies, as well as the open economy conditions. Kazandziska (2019) and Priewe and Herr (2005) have extended this approach to emerging capitalist economies, including further features like the financial system or industrial policies. In a series of papers, Hein and Truger, starting with Hein and Truger (2005), have developed and applied a standardised set of indicators for each macroeconomic policy area and their interaction in several comparative studies of advanced economies.Footnote 15 Here, we will largely follow their approach and examine whether the macroeconomic policy mix in our four countries in the two periods has come close to the post-Keynesian suggestion, thus supporting a stable domestic demand-led growth regime. Alternatively, we will see whether there have been severe deviations, which have been conducive to one of the two unstable extreme regimes, the debt-led private demand boom regime or the export-led mercantilist regime, or, under certain circumstances, even to a stagnating domestic demand-led regime, as we will see below.

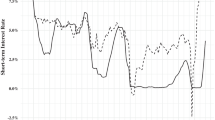

We will examine the following policy indicators for our four countries. For monetary policies of the central bank, we will focus on the relationship between long-term real interest rates and real GDP growth and examine whether condition (1) has been fulfilled. Of course, central banks cannot directly control long-term real interest rates in the credit or financial market at any point in time but only control short-term nominal money market rates. Nevertheless, the use of this and other tools, like open market operations in financial markets in the context of quantitative easing, will have an impact on long-term nominal rates, and taking into account some persistence in inflation trends, also on long-term real rates in the medium run. However, this impact might be asymmetric since raising short-term rates will always drive up long-term rates, whereas lowering short-term rates might not be able to bring long-term rates down in a deep and persistent recession with rising liquidity preference of financial and non-financial actors. That is why we will also look at short- and long-term real interest rates.

For wage policy, we will examine whether condition (2) has been fulfilled and check whether unit labour costs have grown at the target rate of inflation, which for our four countries will be the target rate for the Eurozone as a whole. Furthermore, we will also take into account that rising or falling unit labour cost growth will not proportionally affect the rate of inflation because of incomplete pass-through. Therefore, we will also look at changes in functional income distribution, i.e. at the labour income share.

For fiscal policy, following Eq. (3), we can refer to the government financial balance and the financial balances of the other sectors discussed in Sect. 2. However, since Eq. (3) is an accounting identity, it does not yet allow us to draw clear conclusions regarding deliberate and discretionary fiscal policy interventions. For this purpose, we will need an indicator for Eq. (4), and we will use the changes of the cyclically adjusted budget balance potential GDP ratio (CBR) of the government and relate this to the change in the output gap. To be clear, we are not directly examining Eq. (4) and do not identify potential output with the target full-employment level output, because of the well-known empirical measurement problems and endogeneity features of potential output (Heimberger and Kapeller 2017). Therefore, we do not look at the levels of CBRs and output gaps but only at the annual changes. If output gaps and CBRs move in the same direction, we conclude that fiscal policies are counter-cyclical, lowering (increasing) structural deficits or increasing (lowering) structural surpluses in an economic upswing (downswing). If output gaps and CBRs move in opposite directions, we take this as an indicator of pro-cyclical fiscal policies, in which governments are lowering (increasing) structural deficits or increasing (lowering) structural surpluses in an economic downswing (upswing). Furthermore, we also look at the share of public investment in GDP as an indicator for the growth orientation of fiscal policies. We are aware that this might be an incomplete indicator, because also government consumption expenditures in education, for example, may improve productivity growth.

Finally, we also consider the open economy conditions since they will have an impact on the effectiveness of domestic macroeconomic policies, on the one hand, and will also directly affect the demand and growth regime. We will look at the degree of openness measured by export and import shares of GDP, and the development of price competitiveness, measured by real effective exchange rates. An increase in this rate indicates an appreciation and thus a loss of international price competitiveness. Looking at this indicator, however, does not imply that we assume net exports to be mainly determined by the international price competitiveness of domestic producers. To take into account non-price competitiveness, we also look at the OEC economic complexity index (OEC 2020), following Kohler and Stockhammer (2021).

4 Macroeconomic policy regimes and demand and growth regimes before and after the 2007–2009 crisis

The analysis of the macroeconomic policy regime will apply the indicators presented in the previous section to the two periods examined for our four countries, which are all members of the Eurozone (Table 2). Therefore, for monetary policy, it has to be taken into account that the central bank, the ECB, controls the short-term nominal interest rate for the Eurozone as a whole. So far, it has not targeted country-specific long-term nominal rates in the financial market.Footnote 16 Different inflation rates between countries might then already mean different short- and long-term real interest rates. The differentials in the latter are also affected by country-specific long-term nominal rates, in particular since the start of the Eurozone crisis in 2010 (De Grauwe 2012; Hein 2013/14). For the assessment of the effects of wage policies via functional income distribution, it has to be considered that aggregate demand in all four countries examined here has been estimated to be wage-led (Hein 2014, Chapter 7; Onaran and Obst 2016). We can only provide a stylised interpretation of the developments in each country against the background of our indicators, neither being able to go too deep into the details of macroeconomic policies in the respective countries before and after the 2007–2009 crises nor will we be able to link these developments back to the financial systems in the four countries, which are important for the possibilities of debt-financed expansion, collapse and contraction, and thus also have an impact on the macroeconomic demand and growth regime. For these, we can only refer to some country case studies by other authors, i.e. Ferreiro et al. (2016) on Spain, Detzer and Hein (2016) on Germany, Cornilleau and Creel (2016) on France, and Gabbi et al. (2016) on Italy.

4.1 Spain

During the 2001–2009 period (Tables 2 and 3), Spain benefitted from a strongly expansionary monetary policy stance, which stemmed from Spain’s high inflation and GDP growth rates as compared to other Eurozone member states. High inflation, driven by nominal unit labour cost growth well above the ECB inflation target of ‘below, but close to 2%’ (Fig. 7), led to relatively low real interest rates, such that the difference between the long-term real interest and real GDP growth was negative before the financial and economic crises 2007–2009 (Fig. 8). Despite high nominal unit labour cost growth, the labour income share was falling relative to the previous decade. Furthermore, Spain followed a pro-cyclical fiscal policy stance from 2001 to 2004, when structural deficits fell while the output gap was deteriorating (Fig. 9). Between 2005 and 2009, Spain’s fiscal policy turned counter-cyclical, balancing the cyclical upturn until 2007 and the sudden and major economic downturn between 2007 and 2009. On average, the CBR changed broadly in line with the output gap. A high public investment-GDP ratio was conducive to aggregate demand and growth. High nominal unit labour cost growth and high inflation contributed to the increase in Spain’s real effective exchange rate and the associated loss in international price competitiveness, with comparatively low non-price competitiveness as indicated by the low economic complexity index.

Nominal unit labour costs, annual growth and ECB inflation target, in per cent, 2001–2019. European Commission (2019), authors’ calculations and representation

Real long-term interest minus real GDP growth rate, percentage points, 2001–2019. Source: European Commission (2019), authors’ calculations and representation

Spain—cyclically adjusted budget balance (CBR) and output gap, in percent of potential GDP, 2001–2019. Source: European Commission (2019), authors’ representation

Spain’s macroeconomic policy regime in the period 2001–2009 seems to have contributed to the emergence of the debt-led private demand boom regime in this period, as derived in Sect. 2. The extremely low real interest rates and easy access to credit stimulated deficit-financed investment and private household consumption, the latter in the face of falling wage shares. The fiscal policy followed a more counter-cyclical stance on average and high public investment-GDP ratios fuelled private investment through crowding-in effects. As a result of these developments, large private sector deficits occurred and private consumption and investment became the main drivers of growth, while housing and asset price bubbles were swelling. The downside of this trend was Spain’s loss of price competitiveness, which, combined with low non-price competitiveness and the economy’s comparatively high growth rates, led to negative growth contributions of net exports and a worsening current account, and thus, to large financial surpluses of the external sector.

In the second period of consideration, 2010–2019, the Spanish macroeconomic policy regime changed considerably (Tables 2 and 3). Monetary policy conditions became restrictive, in particular between 2008 and 2015, through a combination of low real GDP growth and low inflation, on the one hand, and rising long-term interest rates, on the other hand (Fig. 7). The latter was due to rising spreads between short- and long-term nominal rates in the course of the Eurozone crisis starting in 2010 (Hein 2013/14). Monetary policy conditions eased from 2015 on when Spain’s growth performance improved gradually, financial markets calmed and the ECB increasingly made use of unconventional monetary policies in order to bring long-term nominal interest rates down. Wage policies turned deflationary under the pressure of high unemployment and structural reforms of the labour market: Nominal unit labour cost growth was negative (Fig. 8), driving inflation well below the ECB target, and the labour income share continued to fall. Wage moderation and disinflation contributed to a falling real effective exchange rate and thus to an improvement of international price competitiveness. Spain implemented pro-cyclical fiscal policies in 8 out of 10 years (Fig. 9). This was particularly harmful during the economic recession from 2009 until 2014 when the cut in public expenditures added to the overall fall in private domestic demand triggered by the financial crisis and the need for deleveraging in the private sector. Pro-cyclical fiscal policies were the result of fiscal austerity measures, in line with the EU Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and with the pressure of the European Commission to reduce public deficits by ‘a combination of expenditure restraint and higher revenues’ (European Commission 2013). This also nearly halved the public investment-GDP ratio in the second period. Only since 2016 has the restrictive stance of fiscal policies been relaxed, and neutral or slightly pro-cyclical fiscal policies contributed to the recovery of the Spanish economy.

The strong shift in Spain’s macroeconomic policy regime over the second period has contributed to the shift of the demand and growth regime towards export-led mercantilist, as analysed in Sect. 2. After the financial crisis, Spanish households and corporations had to reduce financial liabilities and deleveraged heavily. Tightening credit standards, rising real long-term interest rates and falling labour income shares dampened private domestic demand in the wage-led Spanish economy. Pro-cyclical fiscal austerity measures contracted domestic demand further. Net exports, and in particular exports, thus became the only growth driver, benefitting from the improved international price competitiveness caused by wage moderation and from higher growth in foreign economies.

4.2 Germany

In the first period, 2001–2009 (Tables 2 and 3), Germany still suffered from the consequences of having lost its key currency status in the EU (Hein and Truger 2005). During the convergence process towards the Eurozone in the 1990s, nominal long-term interest rates of other EU countries had decreased towards the lower German level. Since Germany had lower inflation rates than the other Eurozone countries, its short- and long-term real interest rates turned out to be higher on average. Consequently, the ECB’s uniform monetary policy was restrictive for Germany, which suffered from high long-term real interest rate-real GDP growth differentials until 2006/7 (Fig. 7). Low German inflation levels were mainly attributable to disinflationary nominal unit labour cost growth, which was considerably below the ECB inflation target (Fig. 8). Extreme wage moderation also led to a fall in the labour income share in this period. Fiscal policies had a restrictive stance attempting to comply with the deficit limits of the SGP, breaching the limits several years in a row and provoking an excessive deficit procedure (EDP) by the European Commission (European Commission 2020a). This led to extremely low public investment-GDP ratios and several years of pro-cyclical fiscal policy, especially at the beginning of the decade (Fig. 10). The fiscal policy only turned counter-cyclical in 2006, when Germany’s economic performance gradually improved. On average over the period, the CBR improved in the face of declining output gaps. Wage moderation and low inflation attenuated the nominal appreciation of the euro in this period, such that the real exchange rate appreciated far less than in other Eurozone countries, and Germany improved its price competitiveness within the Eurozone against the background of the highest level of non-price competitiveness as indicated by the complexity index.

Germany—cyclically adjusted budget balance (CBR) and output gap, in percent of potential GDP, 2001–2019. Source: European Commission (2019), authors’ representation

The macroeconomic policy regime of Germany has also contributed considerably to its demand and growth regime in the period 2001–2009 analysed in Sect. 2: A restrictive monetary policy stance, pro-cyclical restrictive fiscal policies and weak public investment constrained domestic demand, which was further curbed by deflationary wage policies leading to decreasing labour income shares in a wage-led economy. Depressed domestic demand, together with improved international price competitiveness and, in particular, high non-price competitiveness,Footnote 17 left growth being exclusively driven by external demand, resulting in current account surpluses and external sector deficits associated with this export-led mercantilist regime generating only mediocre growth in international comparison.

In the second period, 2010–2019 (Tables 2 and 3), Germany was facing an expansionary monetary policy stance. After real interest rates had peaked in 2009, they fell rapidly from 2010 onwards as a result of the low interest rate policies of the ECB and high financial market trust in German financial liabilities. Long-term real interest rate-real GDP growth differentials thus turned negative (Fig. 7). Nominal unit labour costs grew more rapidly as compared to the first period and on average came closer to the target rate of 2% in the second period (Fig. 8). The labour income share slightly improved. Germany continued implementing restrictive fiscal policies after the trough of the economic crisis had been countered with a large-scale fiscal expansion. Although amounting to 6 years of pro-cyclical policies in total, the fiscal stance was less harmful to the economic development given the slowly improving output gap from 2010 onwards (Fig. 10). On average, the CBR was rising while also the output gap improved. The public investment-GDP ratio slightly increased, too. Although the real effective exchange rate continued to rise, net exports and current account surpluses increased, indicating continuously high non-price competitiveness of German products, as indicated by the complexity index.

The gradual change in the macroeconomic policy regime has had an impact on the demand and growth regime, without changing its nature, which remained export-led mercantilist, though to a lesser extent. The shift to expansionary monetary conditions as well as the rise in the labour income share fostered private investment and consumption demand, making them the main drivers of Germany’s more favourable growth performance over the second period. Growth contributions of net exports declined but remained positive so that export and current account surpluses continued to rise. Relatively dynamic private domestic and foreign demand allowed for fiscal consolidation as reflected by decreasing public sector deficits. This was reinforced by the introduction of the ‘debt brake’ that limited federal budget expenses from 2016 on (Detzer and Hein 2016). Therefore, although changes within the German macroeconomic policy regime towards the stimulation of domestic demand occurred, they were not strong enough to reverse the export-led mercantilist demand and growth regime.

4.3 France

During the first period, 2001–2009 (Tables 2 and 3), France was facing restrictive monetary policy conditions between 2001 and 2003 before they turned slightly expansionary until the outbreak of the crisis (Fig. 7). On average, however, they remained restrictive. Nominal unit labour costs grew just slightly above the ECB inflation target (Fig. 8), while inflation was only slightly below the target. The labour income share only saw a small decline in this period. Similar to Germany, the French economy was struggling to respect the SGP deficit limits at the beginning of the 2000s. Although it found itself in a more favourable economic situation, expansionary fiscal policy responses to the slightly falling output gap (2001–2004) violated the SGP and were followed by an EDP (European Commission 2020b). Consequently, fiscal policy became more restrictive from 2004 on (Fig. 11). On average over the period, the CBR declined in the face of falling output gaps. The average public investment-GDP ratio was comparatively high over the period. The international price competitiveness of French producers declined, mainly because of the nominal appreciation of the euro in this period, and net exports fell but remained slightly positive, under the condition of intermediate non-price competitiveness as indicated by the complexity index.

France—cyclically adjusted budget balance (CBR) and output gap, percent of potential GDP, 2001–2019. Source: European Commission (2019), authors’ representation

The macroeconomic policy regime contributed to the French domestic demand-led regime in the first period, as derived in Sect. 2. Growth was driven by domestic demand, and mainly by private consumption, as enabled by a roughly stable labour income share in a wage-led economy. Public expenditure contributed positively to growth, too, by an on average rather counter-cyclical fiscal policy stance and, in particular, by high public investment. Consequently, the financial surpluses of the private sector were almost completely mirrored by corresponding public sector deficits, with only minor foreign sector deficits, and thus current account surpluses on a declining trend.

In the second period, 2010–2019 (Tables 2 and 3), monetary conditions in France remained slightly restrictive after the crisis and turned expansionary only from 2014 onwards (Fig. 7). Therefore, the real long-term interest rate-real GDP growth differential was negative and thus expansionary on average. Nominal unit labour cost growth remained well below the ECB inflation target, but the labour income share improved. Between 2008 and 2011, the French government reacted with a large-scale expansionary fiscal response to the economic crisis (Fig. 11). After 2011, however, fiscal policies turned restrictive again, demonstrating ‘the willingness of government to fulfil, at any price, the Stability and Growth Pact’ (Cornilleau and Creel 2016, p. 230). This resulted in 7 years of pro-cyclical fiscal policies, in particular from 2014 on, when the government expanded the fiscal stance in the face of an improving output gap. On average, the CBR improved in line with the output gap. The share of public investment in GDP remained relatively high. The slowdown in nominal unit labour costs and inflation contributed to a decline in the real effective exchange rate, thus improving international price competitiveness, which, however, did not prevent net exports and the current account from turning negative in the face of intermediate and slightly falling non-price competitiveness.

As analysed in Sect. 2, the French demand and growth regime was not considerably altered from 2001–2009 to 2010–2019 and remained domestic demand-led. The macroeconomic policy regime contributed to this with an on average expansionary monetary policy stance and a slightly rising labour income share in a wage-led economy, both of which were favourable to private domestic demand. High public investments supported domestic demand, whereas pro-cyclical fiscal policies were partly contractionary.

4.4 Italy

In the first period, 2001–2009 (Tables 2 and 3), monetary policy conditions in Italy were restrictive, i.e. long-term real interest rate-real GDP growth differentials were positive. With above-average inflation rates, real interest rates were lower than in other Eurozone countries, i.e. Germany or France. However, with low real GDP growth rates, the monetary policy stance was contractionary nonetheless (Fig. 7). Nominal unit labour cost growth was well above the rate consistent with the ECB inflation target, in particular in the early 2000s (Fig. 8), while labour income shares decreased considerably. The fiscal policy stance in this period was relatively volatile: Periods of expansionary and restrictive fiscal policies alternated in a frequency of 2 to 3 years, amounting to 6 years of pro-cyclical fiscal policies (Fig. 12). On average, the CBR increased while output gaps were falling. The public investment-GDP ratio was comparatively high, while Italy was struggling to fulfil the requirements of the SGP (European Commission 2020c). High unit labour cost growth and inflation above target undermined the international price competitiveness of Italian producers, as indicated by the rise in the real effective exchange rate. Non-price competitiveness, reflected by the complexity index, was not as strong as in Germany and France.

Italy—cyclically adjusted budget balance (CBR) and output gap, in percent of potential GDP, 2001–2019. Source: European Commission (2019), authors’ representation

The Italian macroeconomic policy regime in this first period was very restrictive and contributed to a stagnating domestic demand-led regime, as derived in Sect. 2. Demand was exclusively driven by private household consumption which, in the traditional bank-based Italian financial system, could not increase beyond current income levels (Gabbi et al. 2016), and by government consumption. The investment was constrained by low growth expectations and high real interest rates. Price-sensitive Italian exports suffered from real exchange rate appreciation, leading to falling net exports, with only intermediate non-price competitiveness.

In the second period, 2010–2019 (Tables 2 and 3), the monetary policy stance for Italy turned even more restrictive. Low short-term interest rate ECB monetary policies generated a negative short-term real interest rate. But, similar to Spain, this was not sufficient to bring long-term real rates down because of increasing risk premia and rising spreads in financial markets. With stagnant growth, Italy thus suffered from high real long-term interest rate-real GDP growth differentials (Fig. 7). Wage policies were put under pressure, and nominal unit labour cost growth fell well below the threshold given by the ECB inflation target (Fig. 8). However, the labour income share stabilised and did not fall further. High real interest rates, economic stagnation and EU pressure led to severe austerity policies. Italy’s fiscal policies did not react to the strongly deteriorating output gap in the Great Recession 2008/2009 (Fig. 12). When the Eurozone crisis hit and Italy fell into a second recession 2012/2013, fiscal policy even responded in a strongly restrictive way, reinforcing the downturn. Public investment declined significantly. Both fiscal and monetary policies only eased from 2014 on when financial markets calmed, and ECB monetary policy remained constantly expansionary. Depressed nominal unit labour cost growth and low inflation improved the international price competitiveness of Italian producers, as indicated by the fall in the real effective exchange rates.

The highly restrictive Italian macroeconomic policy regime has forced the shift in the demand and growth regime, from stagnant domestic demand-led to stagnant export-led mercantilist. High real long-term interest rates and restrictive monetary conditions, pro-cyclical fiscal policies in two recessions and severe cuts of public investment constrained domestic demand in the face of stagnating household income over the whole period. Together with the improvement of international price competitiveness, this made net exports the only rising component of aggregate demand, leading to export and current account surpluses in this period and making Italy a stagnating export-led mercantilist economy.

5 Summing up and conclusions

In this paper, we have tried to contribute to the recent debate on demand and growth regimes in modern finance-dominated capitalism, linking it with the post-Keynesian research on macroeconomic policy regimes in order to understand the role of macroeconomic policies for the changes in demand and growth regimes. For this purpose, we have first examined the demand and growth regimes for the big four Eurozone countries France, Germany, Italy and Spain, applying a well-established procedure based on growth contributions and sectoral financial balances, for the periods 2001–2009 and 2010–2019. Then, we have used a set of indicators for the macroeconomic policy regime, consisting of monetary, fiscal and wage policies, as well as the open economy conditions, and linked them to the demand and growth regimes and their changes from the first to the second period.

Our four country cases have shown that the macroeconomic policy regime has had an important impact on the emerging type of demand and growth regime and the changes in regimes after the 2007–2009 crises. This impact has not only been exerted by fiscal policies, as pointed out by Hein (2019), Hein and Martschin (2020), Hein et al. (2020) and Kohler and Stockhammer (2021), for example, but by the whole macroeconomic policy mix or regime. It was the combination of monetary, wage and fiscal policies, together with the open economy conditions, which has affected the type and the changes of the demand and growth regimes.

The Spanish debt-led private demand boom regime of the period leading to the 2007–2009 crises was fostered by expansionary monetary policy effects of the unified ECB policies, together with expansionary fiscal policies. Wage policies exerted a contractionary impact, which, however, was over-compensated by credit-financed demand and open economy conditions deteriorated. In the second period, the contractionary impact of deleveraging of the private sector was reinforced by contractionary effects of monetary policies and austerity-oriented fiscal and wage policies. Together with the improvement of the open economy conditions, this paved the way for the export-led mercantilist demand and low growth regime.

This Spanish macroeconomic policy regime in the second period bears some similarities with the export-led mercantilist regime of Germany in the first period. The latter was also reinforced by contractionary monetary policy effects of unified ECB policies, contractionary wage policies and partly contractionary fiscal policies. Different from Spain in the second period, German international price competitiveness slightly declined in the first period, without negatively affecting German exports because of high non-price competitiveness. In the second period, the monetary and wage policy stance turned expansionary in Germany, but fiscal policy became more contractionary. This made the export-led mercantilist regime less extreme but did not yet fundamentally change it.

The French domestic demand-led regime in the first period was stabilised by expansionary fiscal policy and partly wage policy, whereas the monetary policy stance imposed by unified policies of the ECB was negative, and external price competitiveness deteriorated. In the second period, the domestic demand-led regime could draw on expansionary effects of ECB monetary policies, whereas fiscal policies turned partly contractionary, as did wage policies, and international price competitiveness improved, without significantly stimulating net exports.

The Italian domestic demand-led regime in the first period was different from the French one, because the macroeconomic policy regime was contractionary in every respect, monetary, fiscal and wage policies, as well as open economy conditions, causing a stagnating demand and growth regime. Although in the second period the contractionary stance of wage policies partly turned, in the face of very restrictive monetary and fiscal policies and improving international price competitiveness, this reinforced a stagnating export-led mercantilist regime.

Methodologically, first, our approach supports the usefulness of the identification of demand and growth regimes according to growth contributions of the main demand components and financial balances of the macroeconomic sectors also for the post-2007–2009 crises period. This allows for an understanding of the demand sources of growth—or stagnation, if there is a lack of demand—of how these sources are financed and of potential financial instabilities and fragilities. Second, when it comes to the economic policy drivers of demand and growth regimes as well as their respective changes, we have shown that the exclusive focus on fiscal policies is too limited and that it is the macroeconomic policy regime that matters; that is the combination of monetary, fiscal and wage policies, as well as the open economy conditions.

Notes

See also Hein (2019), Stockhammer (2012, 2015), van Treeck and Sturn (2013), the contributions in Hein et al. (2016) and several others. These macroeconomic features of financialisation have been derived from the broad and extensive literature on changes in the structure, institutions and power relationships in modern capitalism since the early 1980s. Some recent overviews can be found in Guttmann (2016), Palley (2013), Sawyer (2013/2014) and van der Zwan (2014).

See Davis (2017) for a recent review of empirical evidence on the effects of financialisation on investment in the capital stock.

Econometric research based on demand-driven post-Kaleckian distribution and growth models has shown that most of the advanced capitalist economies, including the EU-15, tend to be wage-led, that is a falling wage share will dampen aggregate demand and growth (Hartwig 2014; Hein 2014, Chapter 7; Onaran and Obst 2016; Onaran and Galanis 2014).

For further references, see the PKES Working Paper version of this paper at: http://www.postkeynesian.net/downloads/working-papers/PKWP2023.pdf. See also the review in Akcay et al. (2021).

Since the EA-12 only came into the existence with the accession of Greece in 2001, this explains the starting year of our first period.

This section partly draws on the analysis of the demand and growth regimes in the Eurozone (EA-12) countries for the period leading to the 2007–2009 crises (2001–2009) and after (2010–2019) that we have provided in Hein and Martschin (2020). Here, we will focus in more detail on the four countries of interest in the current paper, France, Germany, Italy and Spain, and, for comparison, the EA-12 as a whole, and then link the macroeconomic demand and growth regime analysis to the macroeconomic policy analysis in Sect. 4.

For a recent study on the role of emerging capitalist economies, characterised by dependent financialisation and low positions in the international currency hierarchy, in the global imbalances before and after the 2007–2009 crises, see Akcay et al. (2021).

See, for example, Hein and Martschin (2020) for an outline on how a sustainable full-employment post-Keynesian macroeconomic regime for the Eurozone could look like.

Of course, if the private sector is in deficit and the current account is balanced, the government sector has to be in surplus.

For further references, see the PKES Working Paper version of this paper at: http://www.postkeynesian.net/downloads/working-papers/PKWP2023.pdf.

High non-price competitiveness for German exports has been confirmed in several studies. See the recent econometric study by Neumann (2020) and the literature review contained therein.

References

Akcay, Ü, Hein, E, Jungmann, B (2021) Financialisation and macroeconomic regimes in emerging capitalist economies before and after the Great Recession. Working Paper 158/2021. Institute for International Political Economy (IPE), Berlin.

Arestis P (2013) Economic theory and policy: a coherent post-Keynesian approach. European Journal of Economics and Economic Policies: Intervention 10(2):243–255

Arestis P, Sawyer M (eds) (2012) The Euro Crisis. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Baccaro L, Pontusson J (2016) Rethinking comparative political economy: the growth model perspective. Politics & Society 44(2):175–207

Baccaro, L, Pontusson, J (2018) Comparative political economy and varieties of macroeconomics. MPIfG Discussion Paper 18/10. Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne.

Behringer, J, van Treeck, T (2017) Varieties of capitalism and growth regimes: the role of income distribution. Forum Macroeconomomics and Macroeconomic Policies (FMM) Working Papers 9/2017. Hans Boeckler Foundation, Düsseldorf.

Belabed C, Theobald T, van Treeck T (2018) Income distribution and current account imbalances. Cambridge Journal of Economics 42(1):47–94

Bibow, J (2015) The euro’s savior? Assessing the ECB’s crisis management performance and potential for crisis resolution. IMK Study 42. Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK) at Hans Boeckler Foundation, Duesseldorf.

Carlin W, Soskice D (2009) Teaching intermediate macroeconomics using the 3-equation model. In: Fontana G, Setterfield M (eds) Macroeconomic Theory and Macroeconomic Pedagogy. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, pp 13–35

Carlin W, Soskice D (2015) Macroeconomics: institutions, instability, and the financial system. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Cornilleau G, Creel J (2016) France, a domestic demand-led economy under the influence of external shocks. In: Hein E, Detzer D, Dodig N (eds) Financialisation and the Financial and Economic Crises: Country Studies. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 214–233

Davis LE (2017) Financialization and investment: a survey of the empirical literature. Journal of Economic Surveys 31(5):1332–1358

De Grauwe P (2012) The governance of a fragile Eurozone. Australian Economic Review 45(3):255–268

Detzer D (2018) Inequality, emulation and debt: the occurrence of different growth regimes in the age of financialization in a stock-flow consistent model. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 41(2):284–315

Detzer D, Hein E (2016) Financialisation and the crises in the export-led mercantilist German economy. In: Hein E, Detzer D, Dodig N (eds) Financialisation and the financial and economic crises: country studies. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 163–191

Dodig N, Herr H (2015) Current account imbalances in the EMU: an assessment of official policy responses. Panoeconomicus 62(2):193–216

Epstein GA (2005) Introduction: financialization and the world economy. In: Epstein GA (ed) Financialization and the World Economy. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 3–16

European Commission (2013) Commission Opinion of 15.11.2013 on the Draft Budgetary Plan of Spain. https://ec.europa.eu/info/files/commission-opinion-15112013-draft-budgetary-plan-spain_en.

European Commission (2019) Annual Macro-Economic Database (AMECO), November. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/indicators-statistics/economic-databases/macroeconomic-database-ameco/ameco-database_en#database.

European Commission (2020a) Germany – Excessive Deficit Procedures. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-policy-coordination/eu-economic-governance-monitoring-prevention-correction/stability-and-growth-pact/corrective-arm-excessive-deficit-procedure/closed-excessive-deficit-procedures/germany_en.

European Commission (2020b) France – Excessive Deficit Procedures. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-policy-coordination/eu-economic-governance-monitoring-prevention-correction/stability-and-growth-pact/corrective-arm-excessive-deficit-procedure/closed-excessive-deficit-procedures/france_en.

European Commission. (2020c) Italy – Excessive Deficit Procedures. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-policy-coordination/eu-economic-governance-monitoring-prevention-correction/stability-and-growth-pact/corrective-arm-excessive-deficit-procedure/closed-excessive-deficit-procedures/italy_en.

Ferreiro J, Gálvez C, González A (2016) Financialisation and the economic crisis in Spain. In: Hein E, Detzer D, Dodig N (eds) Financialisation and the financial and economic crises: country studies. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 89–114

Fritsche U, Heine M, Herr H, Horn G, Kaiser C (2005) Macroeconomic regime and economic development: the case of the USA. In: Hein E, Niechoj T, Schulten T, Truger A (eds) Macroeconomic policy coordination in Europe and the role of the trade unions. ETUI, Brussels, pp 69–107

Gabbi G, Ticci E, Vozzella P (2016) The transmission channels between the financial and the real sectors in Italy and the crisis. In: Hein E, Detzer D, Dodig N (eds) Financialisation and the financial and economic crises: country studies. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 234–254

Guttmann R (2016) Finance-led capitalism: shadow banking, re-regulation, and the future of global markets. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Hall PA, Soskice DW (2001) Varieties of capitalism: the institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Hartwig J (2014) Testing the Bhaduri–Marglin model with OECD panel data. International Review of Applied Economics 28(4):419–435

Heimberger P, Kapeller J (2017) The performativity of potential output: pro-cyclicality and path dependency in coordinating European fiscal policies. Review of International Political Economy 24(5):904–928

Hein E (2011) Redistribution, global imbalances and the financial and economic crisis – the case for a Keynesian New Deal. International Journal of Labour Research 3(1):51–73

Hein E (2012) The macroeconomics of finance-dominated capitalism – and its crisis. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Hein E (2013) The crisis of finance-dominated capitalism in the Euro Area, deficiencies in the economic policy architecture and deflationary stagnation policies. J Post Keynes Econ 36(2):325–354

Hein E (2014) Distribution and growth after Keynes: a post-Keynesian guide. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham