Abstract

The state and its role in technological innovation and social justice have become, once again, fashionable topics of political and economic debate. A number of innovation theorists argue that never more than today, it is necessary to rethink the state’s entrepreneurial role in society and welfare. Their argument provides justification for the existence of the state, going beyond classical political theory and especially contractarian accounts of legitimacy and obligation. It emphasises the ability and willingness of the state to take risks and reduce uncertainty of economic agents for the sake of innovation that can make everyone better off. This paper insists that although the risk-taking argument of innovation theorists deserves further attention and analysis, it should not be abstracted from a holistic politico-theoretical approach to the state. Such an approach is necessary for a critical understanding of the complex set of predominantly political institutions which compose the state and which have been historically developed to guarantee social evolution. Any risk-taking for innovative enterprise and mission-oriented investment ought to be justified and legitimised on the grounds of principled democratic procedures. This implies that innovation itself is a value-laden political process, requiring participation in the decision-making and standards of fairness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the second decade of the twenty-first century, the state and its role in technological innovation and social justice appear to have become, once again, fashionable topics of political and economic debate. A number of innovation and political theorists (Mazzucato 2014, 2016; Perez 2016; Schot and Steinmueller 2016; Lundvall 2013; Block and Keller 2011) argue that never more than today, it is necessary to rethink the state’s entrepreneurial roleFootnote 1 in society and welfare. Their argument provides justification for the existence of the state not only as a set of institutions that guarantees social evolution through protection of markets but also as an entity capable of creation of markets in risky areas of knowledge and technology. This renewed defence of the state moves beyond classical political theory and especially contractarian theories of legitimacy and political obligation (Hobbes 1991; Locke 1960; Rousseau 1968). It emphasises the ability and willingness of the state to take risks and reduce uncertainty of economic agents for the sake of innovation that can make everyone better off.

This paper insists that although the risk-taking argument of innovation theorists deserves further attention and analysis, it should not be abstracted from a holistic politico-theoretical approach to the state. Such an approach is necessary for a critical understanding of the complex set of predominantly political institutions which compose the state and more specifically, the democratic state that legitimises particular forms of risk-taking. Given that the authority of the democratic state (i.e. the power to shape discourses and behaviours) is derived from peopleFootnote 2 themselves (Hay and Lister 2006), any risk-taking for innovative enterprise and mission-oriented investment (Mazzucato and Pena 2015) ought to be justified and legitimised on the grounds of principled democratic procedures. This implies that mission-led innovation itself is a value-laden political process (Papaioannou and Srinivas 2018), requiring democratic participation of various publics in the decision-making and standards of fairness. Otherwise, it might lose legitimacy or become an instrument in the hands of an authoritarian state.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 explains the return of the state in innovation. Section 3 briefly revisits competing theories of the state. Section 4 discusses different forms of the entrepreneurial state and examines their legitimacy constraints. Section 5 focuses on mission-oriented innovation as a political process that has to address the question of fairness through social redistributive policies. Section 6 analyses the new role of the state in socially just innovation. Section 7 concludes by summarising the overall argument of the paper.

2 The return of the state in innovation

The modern notion of the state originates in the seventieth century political theory and practice when it emerged as a complex set of institutions claiming sovereignty for itself and enjoying monopoly over the legitimate use of power within a defined territory. According to Hay and Lister (2006: p. 7) ‘The state is referred to for the first time as a distinct apparatus of government which rulers have a duty to maintain and which will outlast their rule, as opposed to an extension of the latter’s innate authority’. This modern notion of the state that is separate from the powers of the ruler (government) and the ruled (citizens) and has distinct functions to perform in economy and society (e.g. protection of private property and national security) became dominant in political studies but not in innovation studies.

In fact, until very recently, the notion of the state as a political institution that has a role to play in the generation of new knowledge and technologies was absent from the area of innovation studies. Hundred years ago, the founding father of this inter-disciplinary area, Joseph Schumpeter (1983), saw clearly the interplay between politics and economics, influencing the ideas of Freeman (1974, 1981), Freeman and Perez (1988), Nelson (1984), Lundvall (1985, 1992) and other neo-Schumpeterian thinkers. However, for more than two decades (1990–2010), political notions such as the state had almost vanished from academic and policy debates on technological change and progress. Even the ‘Triple Helix’ and the ‘Innovation Systems’ theories which focus on complex institutional dynamics such as university-industry-government relations and their impact on innovation tended to reduce the role of the state in facilitating interactive learning and regulating markets (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff 1995; Leydesdorff and Meyer 2006; Nelson 1992; Lundvall 2007). This is partly because of the fact that politics and the state were attacked and increasingly dismantled during the peak of neo-liberalism in Western economies (Mazzucato 2014) and partly because of the domination of innovation studies by liberal economists who were sceptical of the importance of politics for understanding economics. The latter has overwhelmingly focused on efficiency and growth, overlooking the distributional effects of innovation which are by definition political (Breznitz and Zehavi 2013). It took years to innovation scholars to confess that:

Our field [innovation studies] has uneasy relationship with public administration as well as politics. No doubt this is partly the consequence of the fact that so many of us are economists, a tribe that paradoxically dominates public administration while at the same time harbouring severe doubts about public purposes. This is reflected in our programmes of research and training – we rarely engage with scholars of law, public administration, social policy, or education and even less often with political theory, ethics, or philosophy. (Steinmueller 2013: p. 161).

Although in the 1990s only a few studies emphasised the interdisciplinarity of innovation, engaging with some of these scholars, in the early 2010s, the relationship between innovation studies and political studies begun to warm up again. It was when a number of innovation scholars and political scientists (Mazzucato 2014; Lundvall 2013; Block and Keller 2011; Vallas et al. 2011; Papaioannou 2011; Kaplinsky 2011) discovered that technological progress would not automatically lead to social progress and that the state was in fact behind almost all investments in radical technological revolutions, including the Internet and digital revolution. According to Block (2011; p. 3):

The historical experience with the innovation economy provides powerful arguments against the core assumptions of market fundamentalism. For many technologies, it has not been Adam Smith’s invisible hand, but the hand of government that has proven decisive in their development. Moreover, the innovation economy depends on a series of principles that are at fundamental variance with market fundamentalism.

To support their argument, Block and Keller (2011) as well as other contributors to their edited volume provide a wealth of cases about the state’s involvement in technological innovation. One of these cases is the making of US biotechnology. Vallas et al. (2011) examine the role of federal policy in fostering the birth of this industry. As they point out:

Where most previous accounts assume that the biotechnology revolution was spontaneously generated by confluence of scientific discovery and profit seeking incentives, we contend that political structures and federal policy have played an equally critical but yet insufficiently acknowledged role…Put simply, we contend that explosive growth of biotechnology industry was in many senses orchestrated and shaped from above as an expression of federal initiatives.

The same holds for other civilian technologies, including the web, algorithmic search, the iPhone and the GPS technologies.

The return of the state in innovation was essentially confirmed in 2014 with the publication of Mazzucato’s work on The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths. This work follows a trend of state intervention theory and/or reaffirms the idea of strategic stateFootnote 3 that has been around for more than half century. Before Mazzucato, Schumpeter (1939), Keynesian, neo-Keynesian and Marxist theorists, including Polanyi (1944) and much later Block (1987), debunked the myth of self-regulating markets and stressed the crucial role of the state in economic growth. More recently, other theorists such as Yu (2001: p. 753) criticised the absence of analysis of entrepreneurship in the public sector and insisted that ‘Without entrepreneurial spirit, one cannot fully understand the underlying reasons for policy changes and more importantly of institutional changes.’ Yu draws on the experience of Asian economies in which governments take a leading role in industrialisation. He explains their dynamic growth in terms of the entrepreneurial state. Another theorist, Ebner (2009: p. 370) also ‘… perceives an entrepreneurial role of the state as an integrated component of economic evolution’. But Mazzucato goes further than Yu and Ebner, arguing that the state is not a simple facilitator of economic growth. Rather, it should be understood as a key partner of the private sector when it comes to searching for growth and technological change. This partnership includes offering knowledge platforms, mobilising and empowering actors, co-creating process and product innovations.Footnote 4 Mazzucato’s argument clearly intends to move the current political and economic debate away from ‘market failure’ and ‘state failure’ justifications. Such justifications might indeed encourage policies to fund basic research and infrastructure projects in order to deal with the unwillingness of private firms to invest in high-risk areas. However, they might not push the state to play a ‘visionary strategic role’ in the economy and society. For Mazzucato, that is precisely the problem with current economic theory that guides public policy. It is not inspiring enough of visionary state actions for innovation. Thus, Mazzucato (2014: p. 23) insists that the state needs to be entrepreneurial in order to engage in risk-taking and the creation of a new vision, rather than just fixing market failures. Industrial policy of the entrepreneurial state should become the driving engine of technological innovations which can help accomplish grand missions, e.g. eradicating poverty.

The question that arises is whether any state can become entrepreneurial, playing this new role for a long time, or there are moral, political, epistemological and even contextual constrains to certain forms of state, preventing them from adopting the strategic vision of risk-taking. For example, can relatively young states in the contexts of developing countries become entrepreneurial, taking risks and engaging in co-creation activities with innovators and communities? The answer seems to be in the negative since several developing states especially in North and Sub-Saharan Africa either institutionally lack capacity or fail to perform certain functions, including protection of citizens against fraud and/or theft. Schumpeter was well aware of the importance of institutional specificities of the state in different contexts and historical times. In his theory ‘Country-specific features of the state are derived from institutional settings and social structures as well as from the nature of wealth that reflects the pattern of the development process’ (Ebner 2009: p. 372). By contrast, Mazzucato and contemporary innovation theorists put forward an abstract theory of the entrepreneurial state. Even so, what they have in mind is clearly the nation state in the Western world and perhaps established and emerging state powers in Asia, including China and India. For this reason, it might make more sense to address the above question first in the context of Western liberal state formation and then in the context of high technology (where the main focus of innovation theorists is). For example, can neo-liberal or libertarian forms of state become truly entrepreneurial?

Defenders of neo-liberal or libertarian forms of state were rather quick to dismiss the innovation theorists’ argument for the entrepreneurial state as partisan and shaky in terms of historical evidence. For instance, Worstall (2013) contests the entrepreneurial state argument on the grounds that technological innovation is not a public good and therefore the government is not justified to support research and development (R&D). In a similar manner, Mingardi (2015: p. 608) argues that ‘…in many respects it [the entrepreneurial state argument] suffers from the “is-ought” problem – that is, it makes too many claims about what we ought to be based on statements of what is’. He therefore accuses innovation theorists and especially Mazzucato, for developing arbitrary arguments, overemphasising ‘a tiny bit of history’ of the twentieth century and failing to provide a holistic historical perspective, including the nineteenth century industrialisation that was independent of huge public investment in R&D. In short, Mingardi regards the entrepreneurial state theory as ideological and biased towards a strong public sector. However, analysing his argument, one might also brand it as ideological, suffering from exactly the same problem: lack of historical evidence. Mingardi’s only counter historical examples are focused on the Industrial Revolution, e.g. railways, failing to accept the fact that involvement of the state has been key for setting up collaborative knowledge and innovation ecosystems that delivered new technologies as both intended and unintended consequences of industrial policy. Overemphasising the role of the private sector and dismissing the historical importance of state industrial policy are rather unconvincing strategies for defeating the entrepreneurial state argument of innovation theorists. Although it is true that this argument implies businesses take less risk than the state (Westlake 2014), it is also true that the latter has more substantial involvement in early stages of technological invention than the former. As Block (2018: p. 29) suggests in his latest work on Capitalism: the Future of an Illusion:

…within the parameters of an economy with private ownership and the pursuit of profitability, there is still very wide leeway to decide how large or small a role the state will play, how much inequality will be tolerated, and how deep and broad democratic governance will be.

Block’s suggestion is a response to ‘capitalist illusionists’ such as Mingardi who tend to see the market economy as being free, coherent and above all self-regulating organism that has its own DNA. This view of the market economy fails to understand the micro-level technology development and the role of the state policy in stimulating innovation. As Lall and Teubal (1998) point out, there is no such thing as a market for setting priorities in technology. Visionary and strategic choices have to be made by governments. However, governments can often choose to be only mobilizers and as such incapable of orchestrating local industries.

Of course, despite the strength of their argument, it is fair to say that Block and innovation theorists, including Mazzucato, neither define the state nor provide a holistic theory of the state functions and institutions. Therefore, in their theory, certain historical, political, epistemological and contextual constraints of the state are ignored or overlooked in such way that a false impression is given: all forms of the state can potentially be entrepreneurial without constraints and legitimacy conditions. Thus, for innovation theorists, it is simply a matter of convincing governments, no matter their liberal democratic or authoritarian profile, about the importance of mission-oriented innovations of the state. As such, their argument for a strategic vision of risk-taking is predominantly political. It requires the political design of institutions such as BNDES, Brazil’s national development bank and SITRA, Finland’s national innovation agency to promote innovation through risky investments. Therefore, the key issue is what politico-theoretical understanding of the state is presupposed of their argument. To address this issue, one should be briefly reminded of the classical, modern and contemporary theories of the state. One should revisit the rationales of these theories for and against specific state functions. The origins of the state are very much associated with these competing theories (Jessop 2016).

3 Competing theories of the state

To begin with classical theories of the state, these include Machiavelli’s The Prince (1532), Hobbes Leviathan (1651), Locke’s Two Treatises of Government (1698) and Rousseau’s The Social Contract (1762). Despite their differences and distinct arguments, these theories are concerned with justifying the state as a neutral agent and benevolent authority that sets the terms and the conditions of social evolution. Therefore, political obligation is translated into a process through which each individual accepts to become subject of the state, owing duties to the state itself (Hay et al. 2006). In the case of Machiavelli and Hobbes, the authority of the state is absolute. Although Machiavelli’s Prince claims absolute authority over a specific geographical area, Hobbes’ Leviathan maintains peace in the transition from the state of nature to civil society. For Hobbes, the state of nature is synonymous to war and therefore the Leviathan is justified as an absolute authority that claims and enjoys a monopoly over legitimate use of force to achieve its objectives. In his famous passage, in Chapter XIV, he stresses:

And because the condition of man (as hath been declared in the precedent chapter) is a condition of warre of everyone against everyone; in wich case everyone is governed by his own Reason; and there is nothing he can make use of, that may not be a help into him in preserving his life against his enemies. It followeth, that in such condition, every man has a Right to everything; even to on another’s’ body. And therefore, as long as this natural Right of everyman to everything endureth, there can be no security to any man…(Hobbes 1991: p. 91).

Hobbes clearly understands the rationale and key function of the state to be the authoritarian maintenance of peace and security in civil society. Therefore, he is against functions which might bring war back to civil society, including the distribution of certain liberties, e.g. individual rights. By contrast, Locke and Rousseau understand the rationale for the state to be the liberal maintenance of freedom in civil society through general rules that everyone can observe and follow. For both thinkers, the hypothetical state of nature is an inconvenient state of affairs, and therefore, there is advantage for people to accept the political state as a neutral authority that equally preserves the property and freedom of everyone. According to Locke:

…in the State of Nature, everyone has the Executive Power of the Law of Nature, I doubt not but it will be objected, That it is unreasonable for Men to be judges in their own cases, that self-love will make Men partial to themselves and their Friends …And hence nothing but confusion and Disorder will follow, and that therefore God hath certainly appointed Government to restrain the partiality and violence of Man. I easily grant, that Civil Government is the proper Remedy for the inconveniences of the State of Nature …(Locke 1960: p. 275).

Locke, of course, provides a theological explanation of the emergence of the liberal state. By contrast, Rousseau’s explanation is based on his theory of the general will of people to bring about a social contract for their transition from the state of nature to civil society and the sovereign political state. Rousseau stresses:

…although in civil society man surrenders some of the advantages that belong to the state of nature, he gains in return far greater ones; his faculties are so exercised and developed, his mind is so enlarged, his sentiments so ennobled … what main loses by the social contract is his natural liberty and the absolute right to anything that tempts him and that he can take; what he gains by the social contract is his civil liberty and the legal right of property in what possesses (Rousseau 1968: p. 64).

Classical political theorists’ understanding of the state as an authority or sovereign that comes about to guarantee either the security or the freedom of civil society implies that legitimacy depends on how well these two primary functions are performed. It also implies that the state is able, through its apparatus, to accumulate the necessary knowledge for such performance. The state has distinctive capacities which, according to Marsh (1999: p. 84), arise from two sources:

The first broad source is the public policy agenda. This is the deposit of an extended historical process. The historical residues include collective attachment to particular values, aspirations and anxieties. These frame the agendas that political leaders champion … The second source of distinctive state capacities arises from institutions through which the broader community and particular interests are mobilised, and through which information is disseminated.

Modern theorists of the state such as Max Weber also see it as an organisation that deploys legitimate coercion and physical force to protect citizens’ private property and ensure they are free to exchange goods in the market. Coercive policy instruments are underwritten by legal authority of the state. As Weber points out:

…a compulsory political organisation with continuous operations will be called a “state” in so far as its administrative staff successfully upholds the claim to the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force in the enforcement of its order (Weber 1978: p. 54).

Weber distinguishes between the state and government. Indeed, while governments change very often, the state, as a set of complex institutions, persists and evolves over time (Hay and Lister 2006).

On this point, Weber is also in agreement with Marx. Of course, Marx criticised the liberal state as an instrument of the ruling class. This instrument is structurally dependent on the economic base of society, i.e. capitalism. Indeed for Marx (1967), any form of political organisation, including the state, corresponds to the form of economic organisation. However, he also recognised the dynamism and the power of the capitalist state. In his Critique of Hegel’s Doctrine of the State, he insists the set of complex institutions that forms the state is not static but is evolving through the relationship between freedom and necessity (Marx 1975).

Although Marx never provided a complete theory of the state, his instrumentalist position has become very influential among Marxists and neo-Marxists. From Lenin and Gramsci to Miliband, Poulantzas and Jessop, these approaches emphasise the role of the state in reproducing exploitative capitalist relations in the market. However, they also stress the importance of non-economic factors, including discursive factors of morality, politics and culture, for consolidating the hegemony of the ruling class over the working class (Gramsci 1971). Although these factors are causally less determinant of the state than economic structures, they should not be overlooked. According to Poulantzas (2014), the state enjoys a relative autonomy from the ruling class and from society. Autonomy implies the ability of the state to take an independent view of its vision and strategic economic priorities. To put it another way, it is not simply an instrument, as Miliband (1969) thought, in the hands of the ruling class or an apparatus, as Althusser (1971) thought, in charge of social cohesion in a class-divided society. Rather, it is a social relationship. According to Poulantzas (2014: p. 128), the state:

…like “capital” it is rather a relationship of forces, or more precisely the material condensation of such relationship among classes and class fractions, such as this is expressed within the state in a necessarily specific form.

This implies that the state is not a ‘unified thing or unitary subject’ (Jessop 2016: p. 54). Rather, it is a relational apparatus of conflicts and contradictions between forces which affect the exercise of power. Yet the state often seeks to become the ‘custodian’ of the general interest of capital, as Block (1987) points out. Within complex dialectic of structures and strategies (Jessop 1990), the capitalist state unfolds as a system that is more open to some political strategies which promote capital accumulation than others. Indeed, following Poulantzas, contemporary Marxists such as Jessop emphasise these strategic-relational aspects of the state, closing the gap between structure and agency. The state becomes an uneven playing field that is characterised by both indeterminacy and contingency. According to Jessop (2016: p. 10):

Broad economic and political visions as well as specific policy paradigms are relevant here. Given the multiplicity of competing visions (at most we find a temporarily dominant or hegemonic discourse) that orient the actions of political forces, this reinforces the view of the state as a polyvalent, polycontextual ensemble.

Contemporary neo-Marxist approaches to the state are contested by liberal pluralists and neo-liberal theorists of public choice who argue that state power is (and ought to be) limited. According to this argument, the limits of the state are not just moral in the sense of lacking justification for interfering with individual freedom in the market but also political and epistemological. First of all, political power is (and ought to be) distributed to different groups of civil society, including lobbying organisations. Early advocates of liberal pluralism such as Laski (1989) criticised the authoritarian state as illiberal and pointed out the importance of constraining those state functions which threat individual freedom. Later pluralists such as Hirst (1989) pointed out the diversity of organisations which prevent the dominance of one particular idea.

The importance of liberty and the distrust of the state are also characteristics of the public choice approach to institutions. Theorists such as Buchanan (1988) and Tullock (1976), and earlier than them Hayek (1978) and Friedman and Schwartz (1963), employed economic methods for the study of politics. As Buchanan (1986: pp. 25–26) sets the whole issue of the theory of public choice ‘it is only when the homo-economicus postulate about human behaviour is combined with politics-as-exchange paradigm that the economic theory of politics emerges from despair’. This implies that political institutions such as the state were explained in terms of utility maximisation or unintended consequences of self-interested individual actions in the market. Only if the latter failed to deliver innovation and prosperity, the state would be justified to intervene in order to fix the problem. Some public choice theorists considered both the market and the state to be imperfect mechanisms. They viewed entrepreneurs and politicians alike as short-term decision-makers. Those who cause markets and states to fail are self-interested individuals with bounded rationality (Simon 1991). When markets fail, certain phenomena such as monopolies and negative externalities need to be corrected by the state.

However, some other theorists, e.g. Hayek (1960), raise epistemological objections to state intervention. In their view, human knowledge is limited and therefore the human mind cannot fully grasp complex phenomena such as the market, let alone fixing them through political institutions. Theorists such as Hayek and later Nozick (1974) endeavour to make the epistemological and moral case for a neo-liberal or libertarian minimal state. The latter is only legitimate to provide national defence and policy services to citizens, avoiding redistributive functions (Papaioannou 2010, 2012).

4 Forms of the entrepreneurial state and their legitimacy constraints

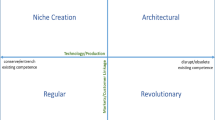

The return of the state in innovation, especially through Mazzucato’s argument about the strategic vision of risk-taking, is driven by a policy critique of the public choice theory of market failure (Mazzucato 2014). However, it fails to acknowledge competing theories of the Western liberal state which identify certain political constraints and conditions of legitimacy for each form of the state. It might be argued that the proposed alternative of the entrepreneurial state, even though plausible and empirically founded, cannot take any form of the state without such constraints and conditions in place. This implies that its strategic vision of risk-taking is constrained by the legitimacy requirements of each form of the state whether authoritarian, liberal, relative autonomous welfare state and neo-liberal or libertarian state. In other words, no form of the state can be legitimate to impose its risk-taking vision on citizens unless the envisaged innovation can support its basic functions. Lack of legitimacy implies lack of collective or national mobilisation for mission-oriented innovations through risky instruments. Let us now examine the legitimacy constraints of each form of the state in relation to innovation theorists’ risk-taking vision in more detail.

Take first the form of an authoritarian entrepreneurial state, in Hobbesian terms. This would be a state that is only legitimate to impose the risk-taking vision on citizens for the sake of peace and security of civil society. This implies using coercion and physical force to push forward undemocratically decided mission-oriented investments for certain innovations, e.g. defence and surveillance technologies, which could maximise social distributive benefits for citizens. But if such benefits, especially peace and security for citizens, are not achieved (or are compromised) in the innovative outcome of these mission-oriented investments, then an authoritarian state in Hobbesian terms would no longer be permitted to function as an entrepreneurial state. To put it another way, a Hobbesian form of entrepreneurial state is perfectly possible provided it can support the distributive functions of protecting peace and security in authoritarian ways, e.g. suppressing human rights and coercing citizens. In fact, states such as China and Singapore appear to have similarities with this constrained form of entrepreneurial state. The authoritarian missions of these states in certain areas of industrial innovation have delivered benefits to citizens since World War II. By assuming entrepreneurial roles via corporations and government investments, Asian authoritarian states have promoted innovative industries for future growth, e.g. ICT, automobiles, biotechnology, and micro-electronics. However, at the same time, they have also suppressed human rights and individual freedoms through their undemocratic mission-led innovations. The theory of entrepreneurial state does not exclude the possibility of authoritarian mission-oriented innovations which are founded upon undemocratic nations of security and not upon democratic processes of participation. Rather, what the theory does is to tolerate authoritarianism as long as missions are innovative.

Another constrained form of entrepreneurial state might be a liberal capitalist state in Lockean or Rousseauan terms. This state would negotiate its risk-taking vision through a social contract for the sake of individual freedom and private property. This would imply formal democratic participation in the decision-making process for investments which are likely to contribute to individual freedom and protect private property institutions. However, if such contributions did not take place (or failed to deliver), then a liberal capitalist state in Lockean or Rousseauan terms would no longer be legitimate to function as an entrepreneurial state. That is to say, a liberal capitalist form of entrepreneurial state is perfectly possible provided it can support the democratic functions of protecting individual property rights and freedoms in liberal ways, e.g. guaranteeing individual rights via a liberal constitution and promoting free exchange of products and services in the market. Several liberal capitalist states in Europe have faced legitimation crises as entrepreneurial states, e.g. France, Germany and Italy, simply because of their inability to withstand accusations of violating constitutional individual freedoms and private property rights in the market or because of their tendency to pick up industrial winners, violating the liberal principle of state neutrality towards different conceptions of the (technological) good. The theory of entrepreneurial state does not suggest that mission-oriented innovations should by definition be in line with human rights such as individual freedom and private property. Therefore, such innovations can easily violate fundamental principles of liberalism for the sake of accomplishing a mission.

A third constrained form of entrepreneurial state might be a welfare state. The latter would still be a capitalist state that is relatively autonomous of the ruling class. This form of the state would promote risk-taking as a political strategy as long as it contributes to increase of social welfare without threatening the narrow interests of the ruling class in capital accumulation. In this sense, mission-oriented investments for generating innovation and growth would be conditional to maximisation of social welfare. This implies, in case that social welfare is not maximised by the innovative outcome of such investments or the interests of the ruling class are compromised by innovative technologies, a welfare state would be criticised for lack of legitimacy to function as entrepreneurial state. This sort of critique was already made to the UK state’s missions in the 1970s, accusing it of creating new poverty and thereby opening the door to neo-liberalism in the 1980s. To put it another way, a welfarist form of entrepreneurial state is perfectly possible provided it can support key welfarist functions, e.g. maximising aggregate preference satisfaction. However, this does not always happen. Often, mission-oriented innovations lose sight of their purpose and end up undermining social welfare. Block and Keller (2011) and Mazzucato (2016) provide a number of examples of innovations which began with the mission to address social welfare issues, e.g. epidemics but ended up appropriated and privatised for the sake of individual welfare.

Perhaps a fourth and most constrained form of entrepreneurial state would be a neo-liberal or libertarian state. The latter would not allow any extensive risk-taking for innovation beyond defence and police services on the grounds that it would be epistemologically impossible and morally indefensible. Although previous forms of entrepreneurial state seem to assume unlimited knowledge that allows for market intervention, a neo-liberal or libertarian state assumes strict epistemological limitations. Such limitations would prevent successful intervention in the market for the sake of mission-oriented innovation, let alone creating the market. The focus of innovation policy would be on growth by means of free competition of technology-based firms. In addition, a neo-liberal or libertarian state would be incompatible with any redistributive policies based on the returns of successful innovations. This incompatibility raises the question of the relevance of the entrepreneurial state argument for the Western capitalist world. A number of capitalist countries have been taken over by the neo-liberal state ideology and therefore now fail to envisage any substantial entrepreneurial activity taking place outside the market realm. In the context of neo-liberalism, innovation policy tends to be technical and depoliticised given the state’s withdrawal from interventionary macro-economic policy. Quite often, state initiatives for macro-economic intervention are branded as illiberal or are criticised on epistemological grounds. Why would one focus on reforming the Western capitalist world through the entrepreneurial state argument instead of shifting efforts to making radical changes of the capitalist mode of production and the social division of labour? The entrepreneurial state argument appears to distract innovation theorists from the real causes of unjust innovation and development namely the contradictory foundations of capitalism itself.

If it is true that the abstract entrepreneurial state can in fact never take any unconstrained form of the state, then it must be also true that the strategic vision of risk-taking can always be conditional on and constrained by the missions and key functions that each form of the state is legitimised to perform. Given such conditions and constraints of legitimacy, we might argue the following: first, some states (e.g. authoritarian, socialist, welfare states) might be legitimate to openly become more entrepreneurial than some other states (e.g. liberal, neo-liberal, libertarian states); second, entrepreneurial interventions of some states (especially liberal or neo-liberal states) might not be sustained for a long time. These states are bound to be short-term ‘institutional entrepreneurs’ due to lack of legitimacy that arises as a result of their failing to maintain neutrality towards particular innovations and/or firms (i.e. picking up winners) or as a result of their failing to control the impact of these innovations on fundamental freedoms (e.g. digital surveillance). The issue of temporality of some entrepreneurial states was first raised by Schumpeter who perceived industrial policy as epochal. However, he emphasised reasons such as the long-run primacy of market forces rather than reasons of legitimacy.

To put it another way, the mission-oriented innovations of say neo-liberal states would always be different from those of say welfare states in terms of depth and temporality. Having said that, all missions have something in common. That is their centralised character. Whether authoritarianism or democratic, all missions tend to require centralised organisation that characterises R&D. Wilson et al. (2007: p. 2) ‘… call this approach to organising R&D “mission mode” and define it by four characteristics: strong commitment backed by sufficient resources, a clear and politically compelling goal, centralised leadership with control over resources, and tight focus on a restricted set of tasks’. Historical mission efforts such as The Manhattan Project (i.e. the mission to develop the first nuclear weapons during World War II) and The War on Cancer in 1971 (i.e. the mission to develop treatment for cancer) in the USA were clearly centralised. Therefore, it is crucial to avoid separating mission-oriented innovations from the state. This observation leads to the following position: an abstract entrepreneurial state that engages in risk-taking activities and creates a new vision for innovation can never receive legitimacy in concrete terms unless it is tied with one of the specific politico-theoretical justifications/forms of the state. However, in doing so, an entrepreneurial state has to endorse innovation as a predominantly political process that promotes key functions and missions of the state. To put it another way, political institutions appear to exercise strong pressure over the directions taken by certain innovations, whether authoritarian, liberal capitalist or indeed democratic directions.

5 Innovation as a political process and the question of fairness

Let us now assume an entrepreneurial state that is tied with and constrained by the form of the welfare state. As has been already argued, any risk-taking strategy by such state would have to be justified on the grounds of maximisation of social welfare. Of course, a risk-taking strategy can mean many things. In Mazzucato’s theory, it is about ‘Knightian uncertainty’. Indeed, Knight (1921) defined entrepreneurship in terms of risk-taking. The entrepreneur is a person willing to put his/her financial security on the line and take risks in the name of a big idea (Mazzucato 2014). This definition of entrepreneurship is different from Schumpeter’s one. Schumpeter rejects the idea that entrepreneurship is about taking on risk. In his Theory of Economic Development (1983: p. 137), he argues:

The entrepreneur is never the risk bear …The one who gives credit comes to grief if the undertaking fails…

Clearly, Schumpeter’s definition of entrepreneurship is built upon the Austrian School of Economics’ theory of human action and particularly the notion of human alertness to profit in the market (Von Mises 1949; Kirzner 1973). Profit opportunities come with risk, but entrepreneurs tend to shift such risk to credit providers. Entrepreneurs mainly focus on discovering or creating new needs and consumer preferences. If Schumpeter is right in what he argues, then Mazzucato’s position is open to discussion. That is to say, the state (especially the liberal and neo-liberal state) cannot play the role of entrepreneur in Schumpeterian terms but rather exercise some limited entrepreneurial functions, including financing new ventures through limited taxation. The state can play the role of industrial leader for a short period of time in order to coordinate the introduction of new technologies into a historically established setting. As Ebner (2009: p. 370) points out ‘… in Business Cycles, Schumpeter maintains that the state may exercise entrepreneurial function in two ways: first-order entrepreneurship involves the enforcing of rules that promote innovation activities of the private sector; whereas second-order entrepreneurship reflects selective policy interventions and the promotion of innovation in public enterprises’.

To put it another way, it is the taxpayers who are ultimate risk bearers of state entrepreneurship and innovation. But the taxpayers cannot be considered as a uniform group of binary assessors of whether the risk-taking in mission-oriented innovations is in line with their expected functions of the state. In fact, they are politically fragmented and hence their views about which precisely functions the state should fulfil may be different. However, even if such differences exist and there are complex trade-offs of costs and benefits, the taxpayers often tend to shape the public opinion for or against specific state plans. If the public opinion is against the state’s plans for mission-oriented innovation, then such plans are illegitimate and cannot be implemented without substantial political cost for government. In the case of the welfare state, this implies that some taxpayers might bear more risk than others for the sake of welfare maximisation through mission-oriented innovation. Therefore, individual rights might be violated, and fairness might be questioned. Take for example a risky investment into a public laboratory for developing a new molecular entity for lung cancer. Some taxpayers might adopt Dworkin’s liberal egalitarian position (Dworkin 1981a, 1981b) claiming that it is unfair to pay for a pharmaceutical innovation that benefits a small group of irresponsible people who have been abusing smoking. Some other taxpayers might question the method through which the impact of pharmaceutical innovation on social welfare can be objectively measured.

In fact, whatever form of state the entrepreneurial state is tied with and constrained by, innovation has to be endorsed as a political process. This implies that the costs and rewards of risky investments in new technologies, whether pharmaceuticals, ICTs, biotechnologies, green technologies and artificial intelligence (AI), have to be distributed according to the political principles of justice which each model of the state adopts as a guidance for its main functions. Thus, if a liberal capitalist state adopts say Rawlsian egalitarian principles of ‘justice as fairness’, i.e. ‘the difference principle’ and the ‘equal liberty’ principle (Rawls 1972), then the costs and rewards of innovation should be arranged in such way that the worse off in society can be made as well off as possible, i.e. maximising the liberty, opportunity, income and wealth of the least advantaged. By contrast, if a liberal capitalist state adopts, say Nozickian individualist principles, i.e. the ‘principle of justice in acquisition’ and the principle of ‘justice in transfer’ (Nozick 1974), then the costs and rewards of innovation should be arranged in such way that each individual’s right to self-ownership is not violated, i.e. strengthening private ownership rights over the fruits of each individual’s talents and capacities.

The historical fact that liberal and neo-liberal states in the Western capitalist world, including the USA and the UK, imposed on their taxpayers risks for the development of radical technologies while they failed to distribute rewards equally, is very much due to their political adoption of implausible principles of justice, i.e. non-egalitarian principles based on notions of absolute self-ownership and individual freedom (Papaioannou 2010; Cohen 1995). These predominantly individualist principles have led to claims of individual appropriation of public resources and therefore to privatisation of rewards of collective endeavours for new technological innovation. As Mazzucato (2014: p. 165) rightly observes:

Often the only return that the state gets for its risky investments are the indirect benefits of higher tax receipts that result from the growth that is generated by those investments. But given the presence of different tax holes and the fact that tax receipts often do not accurately reflect the source of earnings (e.g. income vs capital gains) taxes have proved a difficult way for the state to get back its return for innovation investments.

In fact, what has proved difficult for the state to do in the USA and the UK is to move away from the liberal myth of neutrality towards conceptions of technological goods and ideals. As Block (2011) shows, the neo-liberal state on the one hand claimed consistency with the political ideal of the free market as a fundamental mechanism of neutral and fair distribution of resources and, on the other, picked up winners through industrial policies which favoured specific technologies, e.g. ICT, biotechnology and nanotechnology.

This contradistinction of the neo-liberal state exacerbated inequality that is directly or indirectly linked to technological innovation. For example, given the complex ‘co-evolutionary dynamics’ between new technologies and inequalities (Cozzens and Kaplinsky 2009), the neo-liberal state, in the name of neutrality, refused to provide social safety net to those affected by the skill-biased technological change, e.g. artificial intelligence (AI). But such change was, in fact, financed by the neo-liberal state by means of taxation. Taxpayers’ money was diverted from social welfare to skill-biased technologies as a result of non-neutral political decisions of the neo-liberal state. In this sense, innovation as such was endorsed as a neo-liberal political process that could make winners in the market better off and losers worse off.

6 The role of the state in socially just innovation

Mazzucato’s argument of the entrepreneurial state implicitly identifies the risk-reward nexus of the innovation process within contemporary capitalism as socially unjust. According to her ‘…when the appropriation of rewards outstrips the bearing of risk in the innovation process the result is inequity’ (Mazzucato 2014: p. 185). Mazzucato does not provide any account of why such inequity is wrong or what a socially just innovation process would look like. Therefore, two questions remain open. What is actually a socially just innovation? What is the role of the state in promoting it? Both questions require us to move away from narrow-minded economistic arguments about innovation and towards broader politico-theoretical arguments about generation and diffusion of new technologies. The first point to stress is that, contrary to various liberal egalitarian schools of thought, social justice is predominantly about social relations and not solely about distributions of primary goods, functionings, resources, capabilities, opportunities or well-being. As Anderson (1999) argues, inequality refers not so much to unfair distributions of goods as to social relations between superior and inferior persons. Distributional and relational inequalities are of course different sides of the same currency of justice. As Scanlon (2018: p. 28) points out, those who are better off and those who are worse off are deprived of ‘…the important good of being able to relate to each other as equals’. Whatever material resources or capabilities influence such relations, the fundamental concern of justice is that those of superior rank think they are entitled to inflict violence on inferiors to exclude or segregate them from social life, to treat them with contempt, to force them to obey, work without reciprocation and abandon their cultures (ibid: p. 312).

Indeed, these are what Young (1990) describes as faces of oppression, including marginalisation, hierarchy, exploitation, domination and cultural imperialism. Social egalitarian justice seeks to abolish all faces of oppression so that it can establish:

…a social order in which persons stand in relations of equality … live together in a democratic community, as opposed to a hierarchical one. Democracy is here understood as collective self-determination by means of open discussion among equals, in accordance with rules acceptable to all.

An egalitarian perspective on socially just innovation implies all persons involved in generating products and/or processes new to the firm, new to the market and/or new to the world, including innovators, regulators and publics, stand in relations of equality to others. Thus, they are able to generate and apply knowledge for innovation in conditions of equal self-respect, overcoming knowledge-driven hierarchical divisions and top-down dominated value chains. In an egalitarian innovative society, everyone’s situation and interests in innovation ought to be taken into account in an ‘impartial’ way. Thus, no one could end up worse off or disadvantaged in relation to others. To put it another way, an equal and, at the same time, innovative society is one that has the right quality of relations between all persons and institutions involved in innovation systems. This does not mean that the moral and political objective of equal distribution of material resources, goods, opportunities and capabilities (i.e. currencies of social justice) should be abandoned. In fact, equal distribution of specific currencies of social justice is crucial as long as it influences positively the process of equalisation of social relations of innovation. One could think of this process as a ‘technical democracy’ (Callon et al. 2009: p. 36) that reduces uncertainly in the innovation decision-making by involving everyone. Another could think of the process of equalisation of relations of innovation as a joint inquiry of innovators, regulators and publics that can realise a common interest in social justice in Deweyan terms. For Dewey (1927), there is no such thing as a priori norm. Thus, justice as such appears to be an inquiry for criteria for what counts as a just outcome of innovation. This inquiry involves moral and political judgement.

In her last work, Responsibility for Justice, Young (2011) argues that the moral and political judgement that there is structural injustice of social relations and material resources implies some kind of responsibility. As she explains ‘To judge a circumstance unjust implies that we understand it at least partly as humanly caused and entails the claim that something should be done to rectify it’ (ibid: p. 95). This is exactly where the state comes in. Its role is to respond to citizen’s claim for justice by developing policies which can rectify unjust circumstances. However, not all different forms of the state discussed in this paper are able to play this role. For example, the neo-liberal state in contemporary capitalism considers the unregulated market as responsible to rectify unjust circumstances through a spontaneous process of competition (Hayek 1960, 1967). Thus, in fact, when the neo-liberal state allows the market to spontaneously socialise the risks of innovation and privatise the rewards of successful technologies, it commits structural injustice. Therefore, it should bear responsibility for this injustice. Bearing responsibility means that the state understands its moral obligation to transform structural processes to make the outcome of innovation less unjust. Although it is true that the state is not a single entity and structural injustices are produced by a large number of actors and institutions, it is also true that specific industrial and social policies could be held to account for developing unjust circumstances in knowledge generation and diffusion of new technologies. In Young’s theory, the state and its policies are not independent of us. Therefore, government policy to promote social justice in innovation would require the active support of communities of innovators and publics in order to be effective. These communities also bear responsibility in relation to risky innovations which either fail to meet the needs of disadvantaged people or produce rewards for a tiny minority of well off and privileged actors in innovation systems. All innovations are the result of human actions and not natural forces. In this sense, all actors involved in innovation systems, including innovators, publics and the state, bear political responsibility for those innovations which are unjust and therefore are obliged to correct the injustice. Avoiding such responsibility means that social and political actors are happy to continue contributing to structural innovation processes that make some people vulnerable to deprivation and/or domination.

Let us take as an example the ‘distribution of basic income to all’ proposal or else universal basic income (UBI). This has been debated globally and prompted pilots in several countries, including low- and middle-income countries. The main idea here is that government bears responsibility for supporting new disruptive technologies which make some people worse off, e.g. unemployed and therefore pays a basic income to all members of political community on an individual basis without work or other requirements. Although Van Parijs (1995) has initially defended this idea on the grounds of liberal neutrality towards competing conceptions of the good (e.g. the fact that some people prefer to work and some other people prefer not to work; some people have expensive tastes and others have not expensive tastes), the last two years, UBI has been promoted as a concrete social policy for rectifying innovation injustice. The argument has been that advances in technology, including current automated machines, robots and artificial intelligence (AI), tend to impact unfairly on labour markets, displacing not only relatively low-skilled jobs but also high-skilled services. This argument has been backed by wealth of empirical evidence (Zehavi and Breznitz 2017) which demonstrate the beneficiaries of accelerated innovation are just a few high-skilled workers, whereas the losers are many. For instance, in a recent paper, Alden and Litan (2017: p. 1) discuss the US workforce, arguing that:

Much attention has been paid to the displacement of relatively low-skilled jobs, as autonomous vehicles replace track and taxi drivers, online retail replaces physical stores, and self-checkout machines continue to replace cashiers. But advances in technology will leave few segments of the labour market untouched: new computer programmes are replacing some forms of entry-level legal work and investment planning, while machines with rudimentary artificial intelligence capabilities are already writing basic news stories.

Although this argument may be at odds with other researchers, including Acemoglu and Autor (2011) and Goos et al. (2014), who observe job polarization at both the bottom and the top of the income distribution, it is almost certain that advances in automation and AI technologies will particularly affect developing countries. This is because of the kind of jobs common in these countries, e.g. manual agricultural work, which are susceptible to automation (Schlogl and Sumner 2018). The World Bank (WB) estimates 1.8 billion jobs or two-thirds of the current labour force of developing countries to be under threat by automation technologies (WB 2016). A number of other international agencies, including the International Labour Organization (ILO), have raised the issue of technological threat to the future of employment and the consequences of de-industrialisation for developing countries (ILO 2017). Schlogl and Sumner (2018) consider, for example, the case of Indonesia where an estimated half of all jobs are automatable using existing technologies. Thus, the automation of motorway toll booths has placed in risk 20,000 jobs, leading the country’s Minister of Finance at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to make the case for UBI (Jakarta Post 2017).

Indeed, given the pace of advances in automation and AI technology, one plausible way to rectify unjust ‘creative destruction’ and to maintain reproduction of society as a whole might be to distribute the benefits of technological innovation in a form of UBI. Such distribution would probably reduce inequality in some relations of innovation but would certainly not eliminate it. That is to say, UBI, on the one hand, would guarantee to everyone freedom from poverty and allow people to engage in non-market-oriented social innovation but on the other hand, would not guarantee to everyone end of oppression and equal respect. Ongoing UBI social experiments in various countries indicate positive impacts on peoples’ living conditions, food, security and nutrition, education and productivity, but not on elimination of oppressive gender relations, exploitative and other unjust situations. For instance, Hanlon et al. (2010) demonstrate that various cash transfers in emerging innovative economies such as Mexico, Brazil, South Africa, China and Indonesia have provided social protection and security to the worse off or disadvantaged, raising their incomes and stimulating demand locally. However, redistribution of wealth from the better off to the worse off has only marginally empowered young people, women and communities of colour. In South Africa and India, for example, discriminations based on colour, gender and caste have not been eliminated. The same holds for developed countries such as the UK and the USA where unequal recognition and respect of certain categories of people, including women, influences relations of employment and pay conditions. To put it another way, context matters. As Srinivas and Sutz (2008) show, socially just innovations take different forms in different contexts and conditions of scarcity. They often co-exist with redistributive policies of the state. There is a need for idiosyncratic solutions to problems of innovation injustice.

Justice in innovation cannot be only achieved through the implementation of redistributive policies such as UBI alone. Even if the utopia of monthly allowance enough to live on and deal with the creative destruction of new AI technologies funded by the state could become reality in different contexts (Bregman 2017), the utopia of justice in innovation would not be fully realised unless relations of all actors involved could be equalised. The role of the state in promoting socially just innovation does not then stop in progressive redistribution of resources such as UBI and other benefits of innovation. Indeed, as Mazzucato (2014) suggests, there is strong justification for socialising the returns of state investment in successful technological innovation. However, narrow this suggestion may be (in the sense that there are many ways in which benefits of technological innovation accrue to taxpayers), the fact that ‘… over 20 per cent of corporate profits in the UK go to the public pursue in the form of corporation tax …’ (Westlake 2014: p. 8) does not devaluate Mazzucato’s suggestion as Westlake (ibid) seems to think. On the contrary, it enforces her argument for justice in the distribution of benefits of innovation.

However, a socially just state ought to go beyond that, adopting principles of justice which focus on equalisation of social relations in the innovation process. Such principles are not necessarily distributive (i.e. they do not regard people as equal as long as they enjoy equal amount of resources, opportunities, capabilities) but rather relational (i.e. they regard people as equal as long as they enjoy mutual respect, reciprocation and recognition). Political theorists such as Young (1990), Taylor (1994), Honneth (1995) and Fraser (1997) have consistently elaborated these principles challenging liberal equalitarian arguments of distributive justice. Thus, these theorists built their arguments on claims about equality, participation and recognition made by public activists and campaigners in different contexts. It follows that a socially just state in innovation ought to promote public actions and campaigns which aim to eliminate oppression, arbitrary violence or physical coercion, marginalisation and hierarchical domination from the very process of knowledge generation and development of new technologies (Papaioannou 2018). Although the material basis of these relations is given, other factors, such as race, gender, caste, culture, are determinants. Therefore, the role of the state in social innovation ought to be both contextualised and holistic.

7 Conclusion

This paper has reflected on the recent debate of the entrepreneurial state and its role in technological innovation and social justice. In doing so, it has examined the risk-taking argument of innovation theorists, insisting that they should not abstract from a holistic politico-theoretical approach to the state. Classical, modern and contemporary theorists of the state teach us that there are concrete forms of the state that any entrepreneurial and risk-taking strategy has to be tied with in order to achieve legitimacy. Inevitably, some forms of the state are legitimate to be more entrepreneurial than some other forms of the state. Thus, authoritarian, socialist and welfare states appear to be more legitimate in performing entrepreneurial functions than liberal, neo-liberal and libertarian states. The latter are bound to be short-term entrepreneurial states due to their lack of legitimacy. By contrast, the former are bound to be long-term entrepreneurial states due to legitimacy they can achieve when their mission-oriented activities produce socially just outcomes. This implies that innovation as such is a political process guided by certain principles of justice and contributing to legitimate functions of the state. The historical experience of the neo-liberal state and its contradictory process of innovation that increases inequality, reinforce the importance of justice in the generation and diffusion of new technologies. However, such justice in innovation ought to go beyond distribution and redistribution of resources, and towards the very social relations of generation of new knowledge and technologies which determine the exclusion of certain actors, e.g. the poor, indigenous people and women. An innovative society in which persons stand in relations to equality demands not only elimination of maldistribution but also of misrecognition, marginalisation and exclusion from its innovation system. Future research should explore in detail the idea of justice in innovation as a relational process of progressive society.

Notes

By using the term ‘entrepreneurship’ I mean risk-taking for setting up innovative businesses and creating new markets.

Various political theories have used different terms to describe the ‘people’ who grant the state ‘authority’ including ‘citizens’, ‘taxpayers’ and ‘men’.

This point was made by one of REPE reviewers. I would like to thank him/her for the contribution.

This point was made by one of the REPE reviewers. I would like to thank him/her for the contribution.

References

Acemoglu D, Autor DH (2011) Skills, tasks and technologies: implications for employment and earnings. In: Ashenfelter O, Card DE (eds) Handbook of labour economics. Elsevier Inc., Amsterdam, pp 1043–1171

Alden, E. and Litan, R. E. (2017) ‘A new deal for the twenty-first century’ Council on Foreign Relations, Available: https://www.cfr.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/Renewing_America_Twenty_First_Century_Deal_OR.pdf [Last accessed 24 Jul 2015]

Althusser, L. (1971) Ideology and Ieological State Apparatuses, L. Althusser (Ed.), Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. New York: Monthly Review Press

Anderson ES (1999) What is the point of equality? Ethics 109(2):287–337

Block F (1987) ‘The ruling class does not rule: notes on the Marxist theory of the state’ in Idem, Revising State Theory: Essays in Politics and Postindustrialism. Temple University Press, Philadelphia

Block F (2011) Innovation and the invisible hand of government. In: Block F, Keller M (eds) State of Innovation: the US Government’s Role in Technology Development. Paradigm Publishers, London

Block F (2018) Capitalism: the future of an illusion. University of California Press, Oakland

Block F, Keller M (2011) State of innovation: the US government’s role in technology development. Paradigm Publishers, London

Bregman R (2017) Utopia for realists: and how to get there. Bloomsbury, London and New York

Breznitz D, Zehavi A (2013) ‘What does politics have to do with innovation? Economic Distribution and Innovation Policy in OECD countries’ Collegio Carlo Alberto Notebooks, No.303

Buchanan JM (1986) Liberty, market and state Brighton: Harvester Press

Buchanan JM (1988) Market failure and political failure. Cato J 8:1–13

Callon M, Lascoumes P, Barthe Y (2009) Acting in an uncertain world: an essay on technical democracy. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Cohen GA (1995) Self-ownership, freedom, and equality. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Cozzens SE, Kaplinsky R (2009) Innovation, poverty and inequality: cause, consequence or co-evolution? In: Lundvall B-A, Joseph KJ, Chaminande C, Cheltenham JV (eds) Handbook on Innovation Systems and Developing Countries: Building Domestic Capabilities in Global Setting. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Dewey J (1927) The public and its problems: an essay in political inquiry. Henry Holt, New York

Dworkin R (1981a) What is equality? Part 1: equality of welfare. Philos Public Aff 10(3):185–246

Dworkin R (1981b) What is equality? Part 2: equality of resources. Philos Public Aff 10(4):283–345

Ebner A (2009) ‘Entrepreneurial state: the Schumpeterian theory of industrial policy and the East Asian “Miracle”. In: Cantner U et al (eds) Schumpeterian Perspectives on Innovation, Competition and Growth. spring-Verlag, Berlin and Heidelberg

Etzkowitz H, Leydesdorff L (1995) The Triple Helix: University-Industry-Government Relations, a laboratory for knowledge based economic development. Routledge, New York

Fraser N (1997) Justice interruptus: critical reflections on the “Postsocialist” condition. Routledge, New York

Freeman C (1974) The economics of industrial innovation. Penguin, Harmondsworth

Freeman C (ed) (1981) Technological innovation and national economic performance. Aalborg University Press, Aalborg

Freeman C, Perez C (1988) Structural crisis of adjustment: business cycles and investment behaviour. In: Dosi G et al (eds) Technical change and economic theory. Pinter, London

Friedman M, Schwartz A (1963) A monetary history of the United States 1867–1960. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Goos M, Manning A, Solomons A (2014) Explaining job polarization: routine-biased technological change and offshoring. Am Econ Rev 104(8):2509–2526

Gramsci A (1971) Selections from the prison notebooks. Lawrence and Wishart, London

Hanlon J, Barientos A, Hulme D (2010) Just give money to the poor. Kumarian Press, Sterling

Hay C, Lister M (2006) Introduction: theories of the state. In: Hay C, Lister M, Marsh D (eds) The state: theories and issues. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Hay C, Lister M, Marsh D (eds) (2006) The state: theories and issues. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Hayek FA (1960) The constitution of liberty. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London

Hayek FA (1967) Studies in philosophy, politics and economics. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London

Hayek FA (1978) Law, legislation and liberty. Routledge, London

Hirst P (ed) (1989) The pluralist theory of the state. Routledge, London

Hobbes T (1991) Leviathan. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Honneth A (1995) The struggle for recognition: the grammar of social conflicts. Polity, Cambridge

ILO (2017) The future of work we want: a global dialogue. International Labor Organization, Geneva Available at: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/future-of-work/dialogue/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed 22 June 2020

Jakarta Post. (2017) ‘Non-cash toll will affect 10,000 workers in Jakarta’ The Jakarta Post, September 14. Available at: http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2017/09/14/noncash-toll-will-affect-10000-workers-in-jakarta.html. Accessed 22 June 2020

Jessop B (1990) State theory: putting the capitalist state in its place. Polity, Cambridge

Jessop B (2016) The state: past, present, future. Polity Press, Cambridge

Kaplinsky R (2011) “Bottom of the pyramid innovation and pro-poor growth” IKD Working

Knight, F. (1921) Risk, Uncertainty and Profit, New York: Augustus M Kelley.

Kirzner IM (1973) Competition and entrepreneurship. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Lall S, Teubal M (1998) “Market stimulating” technology policies in developing countries: a framework with examples from East Asia’. World Dev 26(8):1369–1385

Laski HJ (1989) The foundations of sovereignty and other essays. In: Hirst P (ed) The pluralist theory of the state. Routledge, London

Leydesdorff L, Meyer M (2006) Triple Helix indicators of knowledge-based innovation systems. Res Policy 35(10):1441–1449

Locke J (1960) Two treatises of government. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lundvall B-A (1985) Product innovation and user-producer interaction. Aalborg University Press, Aalborg

Lundvall B-A (1992) National systems of innovation: towards a theory of innovation and interactive learning. Pinter, London

Lundvall BÅ (2007) National innovation systems—analytical concept and development tool. Ind Innov 14(1):95–119

Lundvall B-A (2013) Innovation studies: a personal interpretation of the state of the art. In: Fagerberg J, Martin BR, Andersen ES (eds) Innovation studies: evolution & future challenges. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Marsh I (1999) The state and the economy: opinion formation and collaboration as facets of economic management. Political Studies (PS), XLVII 47:837–856

Marx K (1967) Capital, vol 3. Lawrence and Wishart, London

Marx K (1975) Critique of Hegel’s doctrine of the state. In: Colletti L (ed) Karl Marx: early writings. Pelican, London

Mazzucato, M. (2014) The entrepreneurial state: debunking public vs. private sector myths, London: Anthem Press

Mazzucato M (2016) Innovation, the state and patient capital. In: Jacobs M, Mazzucato M (eds) Rethinking capitalism: economics and policy for sustainable growth. Wiley-Balckwell, Oxford

Mazzucato M, Pena CR (eds) (2015) Mission oriented finance for innovation: new ideas for investment-led growth. Policy Network, London

Miliband R (1969) The state in capitalist society: an analysis of the Western system of power. Wedenfeld and Nicolson, London

Mingardi A (2015) A critique of Mazzucato’s entrepreneurial state. Cato J 35(3):603–625

Nelson R (1984) High-technology policies: a five nation comparison. American Enterprise Institute, Washington DC

Nelson RR (1992) National innovation systems: a retrospective on a study. Ind Corp Chang 1(2):347–374

Nozick R (1974) Anarchy, state, and utopia. Blackwell, Oxford

Papaioannou T (2010) Robert Nozick’s moral and political theory: a philosophical critique of libertarianism. The Edwin Mellen Press, New York

Papaioannou T (2011) Technological innovation, Global Justice and Politics of Development. Prog Dev Stud 11(4):321–338

Papaioannou T (2012) Reading Hayek in the 21st century: a critical inquiry into his political thought. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Papaioannou T (2018) Inclusive innovation for development: meeting the demands of justice through public action. Routledge, London

Papaioannou T, Srinivas S (2019) Innovation as a political process of development: are neo-Schumpeterians value neutral? Innovation and Development 9:141–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/2157930X.2018.1535872

Paper 62, Available at: www.open.ac.uk/ikd/publications/working-papers [Last accessed 24 July 2015]

Perez C (2016) Capitalism, technology and a green global golden age: the role of history in helping to shape the future. In: Jacobs M, Mazzucato M (eds) Rethinking capitalism: economics and policy for sustainable growth. Wiley-Balckwell, Oxford

Polanyi K (1944) The great transformation. Beacon Press, Boston

Poulantzas N (2014) State, power, socialism. Verso, London

Rawls J (1972) A theory of justice. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Rousseau JJ (1968) The social contract. Penguin, London

Scanlon T (2018) Why does inequality matter? Oxford University Press, Oxford

Schlogl, L. and Sumner, A. (2018) ‘The rise of the robot reserve army: automation and the future of economic development, work and wages in developing countries’ centre for global development, Working Paper 487. Available at: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/rise-robot-reserve-army-automation-and-future-economic-development.pdf. Accessed 22 June 2020

Schot, J. and Steinmueller, W. E. (2016) ‘Framing innovation policy for transformative change: innovation policy 3.0, science policy research unit (SPRU) working paper, Available at: http://www.johanschot.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Framing-Innovation-Policy-for-Transformative-Change-Innovation-Policy-3.0-2016.pdf. Accessed 22 June 2020

Schumpeter JA (1939) Business cycles: a theoretical, historical and statistical analysis of the capitalist process, vol 1–2. McGraw-Hill, New York

Schumpeter JA (1983) The theory of economic development. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick and London

Simon HA (1991) Organisation and markets. J Econ Perspect 5(2):25–44

Srinivas S, Sutz J (2008) Developing countries and innovation: searching for a new analytical approach. Technol Soc 30:129–140

Steinmueller E (2013) Innovation studies at maturity. In: Fagerberg J, Martin B, Anderson ES (eds) Innovation studies: evolution and future challenges. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Taylor C (1994) The politics of recognition. In: Gutmann A (ed) Multiculturalism: examining the politics of recognition. Princeton University press, Princeton

Tullock G (1976) The vote motive. The Institute of Economic Affairs, London

Vallas SP, Kleinman DL, Biscotti D (2011) Political structures and the making of US biotechnology. In: Block F, Keller M (eds) State of innovation: the US government’s role in technology development. Paradigm Publishers, London

Van Parijs P (1995) Real freedom for all: what (if anything) can justify capitalism. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Von Mises L (1949) Human action. Contemporary Books, Inc., Chicago

Weber M (1978) Economy and society: an outline of interpretive sociology. University of California Press, Berkeley

Westlake, S. (2014) ‘Some thoughts on the entrepreneurial state’ Nesta-UK Blog: https://www.nesta.org.uk/blog/some-thoughts-on-the-entrepreneurial-state/. Accessed 22 June 2020

Wilson, P., Post, S. and Srinivas, S. (2007) ‘R&D models: lessons from vaccine history’ International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, Columbia University, Available at: http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/52899/. Accessed 22 June 2020

World Bank (2016) World development report: digital dividends. World Bank, Washington, DC

Worstall, T. (2013) ‘The intellectual hole at the heart of Mariana Mazzucato’s entrepreneurial state’ Forbes: https://www.forbes.com/sites/timworstall/2013/12/15/the-intellectual-hole-at-the-heart-of-mariana-mazzucatos-entrepreneurial-state/. Accessed 22 June 2020

Young, I. M. (2011) Responsibility for Justice, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Young IM (1990) Justice and the politics of difference. Princenton University Press, Princeton

Yu TF-L (2001) Towards a theory of the entrepreneurial state. Int J Soc Econ 28(9):752–765

Zehavi A, Breznitz D (2017) Distribution sensitive innovation policies: conceptualization and empirical examples. Res Policy 46:327–336

Acknowledgements