Abstract

The increased dependency on technology brings national security to the forefront of concerns of the 21st century. It creates many challenges to developing and developed nations in their effort to counter cyber threats and adds to the inherent risk factors associated with technology. The failure to securely protect data would potentially give rise to far-reaching catastrophic consequences. Therefore, it is crucially important to have national, regional, and global data protection policies and regulations to penalise those engaged in unethical use of technology and abuse the system vulnerabilities of technology. This research paper aims to analyse GDPR inspired Bills in the South Asian Region and to identify their appropriateness for developing a global level data protection mechanism, given that Asian nations are far more diverse than those of the European nations. Against that background, the objectives of this paper are to identify GDPR inspired Bills in the South Asian Region, identify the similarities and disparities, and the barriers to developing a regional level data protection mechanism, thereby fulfilling the need for developing a global level mechanism. This research is qualitative in nature, and with that in mind, the researcher conducted an extensive literature survey of previous research papers, journal articles, previous survey reports and government publications on the above content. Taking account of the findings of the survey, the researcher critically analysed the important parameters identified in the literature review. The key findings of this research indicate that many countries in the South Asian region are in the process of reviewing their current data protection mechanisms, in line with GDPR. In concluding, the researcher emphasised the need to develop adequate data protection mechanisms and believed that going forward it would be the appropriate and practical way to develop a consensus-based regional mechanism that would ultimately enable to develop a lasting global level data protection mechanism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The nations of the world have become an integrated community; just so, the people are having to adapt to rapidly evolving changes in lifestyles, the dependency on progressive advancement of technology is one of them. The introduction of IT systems and advanced computer technology feature prominently amongst many sectors, commercial, governance, shopping, travel, banking, and many more, and the extensive use of IT systems is rapidly becoming a way of life for many. The generation of vast amount of data is a by-product of advanced technology, and this phenomenon continues to grow at an unprecedented rate. The technologies like Artificial Intelligence, the Internet of Things, and Big Data are used to collect data, and collected data is processed and stored, unbeknown to the individual or the public at large. The processing of data in this way continues to challenge the legal framework in every jurisdiction.

In the digitalised world, the right to privacy goes hand in hand with data protection, and it makes the right to privacy an essential element of democratic values. The increasing dependency on technology brings national security to the forefront of concerns of the 21st century and the developing and developed nations face many challenges in their attempts to counter cyber threats, mitigate the risks, and in finding solutions to likely impact arising from the use of the cyberspace. For instance, the military of the United States Army recognises cyberspace as the most important battle space after land, water, and sea [1]. A former CIA director and senior ranked General has stated the cyber threats across the world had a similarity, and the nations should recognise cyberspace as an important battle space and critical part of national security [1].

The absence of a strong response to malicious behaviour would be taken as a weakness in the eyes of the law and, naming and shaming of offenders may not have the desired effect [2]; besides, bringing them to account in such situations will be a challenging task. Therefore, the member states of the EU enacted the GDPR to provide a legal framework setting out guidelines for collecting and processing the personal information of the individuals [3]. In May 2018, the European Union adopted the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a legal measure aimed to provide a set of standardised data protection laws across its member states [4].

This initiative has encouraged the countries outside the EU to revisit their own data protection mechanisms, modelling on the GDPR, that has prompted several nations to begin enacting their Personal Data Protection laws to bring them in to par with GDPR. The member countries of the Association for South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) following the trend, refined and implemented their law/s to uphold the data protection mandate [5]. However, in the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) region, most of the countries are in the process of developing data privacy laws [6], but no visible progress is being made towards producing a region relevant law/s resulting from the SAARC agreements [7]. The Asian nations are extensively diverse than those of the European nations, and their governance systems are driven by the colonial experience and the wide variations in ideological attitudes such as diverse political and religious beliefs, and multilingualism inherent in the fabric of the society make collaboration a challenging one.

The United Nations (UN) General Assembly, in its Resolution on the Right to Privacy in the Digital Age, noted that the rapid pace of technological development attracted users all over the world to modern Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) [8]. The governments and the companies made use of this trend to increase their capacity to undertake surveillance, interception, and data collection processes that would unwittingly risk violation of privacy rights [8]. Given the potentially controversial nature of the issues involved, the UN General Assembly and the Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights stressed on the need to protect privacy rights when the users are connected to online services [8]. Therefore, the case for undertaking an extensive review to develop a consistent legal framework is beyond doubt and is crucially important and vital now more than ever before.

However, there are several countries without sufficient data protection mechanisms, even without any means to protect their citizen’s personal privacy [9], and the reason is the lack of resources and the shortage of professionals with sufficient understanding of the issues [10]. Also, at the national level, each country faced with internal difficulties compelled to grapple with different challenges, which makes it even more important to understand such inhibiting factors and make allowances and flexibility to the adaptation of the framework in emerging scenarios. Despite all the challenges, the case for developing an (having an) international strategy for data security and privacy is important [11]. The need to have a robust and meaningful data protection mechanism should not be underestimated, and it is the most effective or even the only way forward to safeguard personal privacy and national security.

This research paper provides an understanding of the GDPR inspired bills developed by counties in the South Asian region. The researcher seeks to determine whether the mechanisms developed at the national level would contribute to the development of a global level data protection mechanism. To that end, this research paper aims to analyse the GDPR inspired Bills in the South Asian Region and identify the course of action they would take towards the development of a global level data protection mechanism. In pursuing that aim, the objectives of this paper are to identify GDPR inspired Bills in the South Asian Region, identify the similarities and dissimilarities, and identify the barriers to developing a regional level data protection mechanism that would meet the requirement for developing a global level mechanism.

In addressing the research aim, the researcher reviewed available literature surrounding GDPR and GDPR inspired bills in the South Asian region to analyse the contribution of national level data protection mechanisms towards developing a global level data protection mechanism. Except for the article authored by Greenleaf on GDPR inspired bills in the South Asian region, the quantity of research papers covering GDPR inspired bills is minimal in the South Asian Region. He had only focused on Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Nepal, without any discussion on the challenges and barriers those countries faced in accepting and implementing data protection mechanisms had not been discussed. Therefore, the researcher believes that the meaningful analysis of national-level mechanisms and the barriers faced by the countries in the South Asian region highlighted in this paper would make a valuable contribution to existing literature.

General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR)

The European Union (EU) enacted the GDPR [12] governing personal data protection to promote the establishment of a regional strategy for information security based on fundamental rights underpinned by democracy. Amongst other factors, personal data protection is one important element of the rights of the people, and it offers sanctuary to the individuals and makes them feel secure from unethical intrusions to their personal data. The existence of privacy protection regulations will encourage the governments to recognise and acknowledge the differences in privacy interests amongst the countries. That makes it important to have appropriate provisions included in the legal framework to protect the victims affected by privacy breaches.

The collection, use, and disclosure of personal information of individuals are concerning issues in a climate of rapidly developing information processing technology, and an increasing number of people are becoming concerned about their privacy being compromised in the process. Therefore, the overriding concern is how secure collecting, disclosing, processing, and managing personal data is. That leads to emphasising the crucial importance of having adequate data privacy laws around the world.

GDPR prescribes eight Data protection principles, Lawfulness, Fairness and Transparency, Purpose Limitation, Data Minimization, Accuracy, Storage Limitation, Integrity and Confidentiality, Accountability [13]. Some changes have been introduced in data protection by harmonizing the data privacy laws across Europe. The European Union (EU) prohibits data transfer from an enterprise in the EU region to countries that do not match the same level of EU Regulations on data protection [14]. The implication is that an organisation or an individual from any part of the world handling information of EU citizens, even based in an EU member state, come under the purview of GDPR. The new rules also provide the EU citizens with a set of rights, including the right to access and the right to be forgotten personal information [14].

The enterprises that undertake activities relevant to the processing of personal data are required to employ a data protection officer, and [14] reporting of data security breaches is mandatory as recommended by the commission. The enterprises are obliged to alert both their data protection authority and the people affected by the data breaches within 72 h of detection and provide a detailed report of the incident, including a recovery plan proposal for mitigating its effects [14]. Those organisations found to violate the GDPR set rules would be liable for substantial fines. The maximum penalty for a GDPR violation is 20 million euros or 4 percent of a company’s annual global revenue from the year before, whichever is higher [15]. European Union by endorsing the GDPR, has taken the lead in instituting data privacy regulations. It is incumbent on other countries to follow suit and develop a robust, meaningful legislative framework for data protection worldwide.

Some also argue that instead of harmonisation, GDPR would lead to the creation of more national discrepancies and inconsistencies in the current policies [16]. The GDPR has set standards that no data controller would risk ignoring, and other governments will be compelled to level up to allow other economies unhindered access to the single digital market of the EU. There are visible signs that Japan for instance has expressed its intentions to introduce similar provisions to the GDPR [16]. The commercial sector in the UK is making every effort to make GDPR the norm in post-Brexit Britain, and the UK remains committed to the privacy principles enshrined in the EU Regulations. The UK Government has also pledged to introduce a new ‘digital charter’ to ensure the UK remains the safest place to use online facilities [17].

The emerging modern technologies generate vast volumes of data, and it is important to ensure that the information is securely collected, processed, transmitted, stored, and accessed. However, given the enormity of the data generated daily, there will also be a tendency for conflicts to occur in the process of gathering and protecting data, particularly in terms of privacy. In the next section, the researcher focuses on the data protection mechanisms in the South Asian region.

Actions Taken by Countries in the South Asian Region

The eight states of the South Asian region, India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Bhutan, Nepal, Maldives, and Afghanistan, make up the SAARC [18]. It is the data privacy regulations developing hub, there is a strong possibility that South Asia will emerge with several laws that match existing international standards, but the indicators are some countries are well advanced whilst some have not made much progress towards establishing privacy protection ethics in South Asia. At the present time, there are no emerging sign of a SAARC regional initiative materialising in the near future, and the achievement of a successful outcome seems some distance away [6].

Pakistan

In 2005, the Pakistan Ministry of Information Technology circulated a draft law on data protection, but it was not presented to the parliament [19, 20]. It appeared the legislation had been drafted primarily to meet the needs of the country’s software industry to conduct international business rather than to address actual privacy issues [20]. Therefore, this draft legislation seemed to have been a half-baked red herring and fallen short of its applicability to processing personal or corporate data by federal, provincial, or local government institutions [20].

The Personal Data Protection Bill 2020 was introduced by the Ministry of Information Technology and Telecommunications (MOITT) later, but it has not been tabled before the National Assembly or presented to the Senate for its approval up to now [21]. The bill encompasses many provisions that are in line with the international data protection regulatory framework. The legal obligations for data controllers and processors are broadly in par with other international laws, including GDPR, and they encapsulate the requirements to provide notice of consent, retention, disclosure, breach notification, and cross-border transfers [22]. Similarly, the rights of individuals are broadly aligned with those in other jurisdictions and include the right to access and to amend data, to withdraw consent, request for erasure of data, and to request a data controller to cease processing their data [22]. However, certain aspects of the bill remain out of alignment with widely accepted privacy norms, including a potential data localization requirement [23]. One notable element in the bill is the omission of the provision to appoint a Data Protection Officer. However, the power of the personal data protection authority of Pakistan bestows power to formulate responsibilities of the Data Protection Officer [24, 25].

The bill states that a data controller shall not process personal data, including sensitive personal data, unless the data subject has given consent to the processing of the personal data [21]. The bill contains provisions allowing a data subject to give notice in writing to withdraw his/her consent to the processing of personal data, and the data controller, upon receiving such notice will have to stop the processing of personal data [21]. There are exceptions to the rule in cases of public interest, freedom of expression, and the security of the state as and when it becomes paramount. The bill also specifies that critical personal data shall only be processed in a server or data centre located in Pakistan, which indicates that Pakistan is to some extent shadowing the data localisation policies [26].

The transfer of personal data, collated by banks, insurance companies, hospitals, defence establishments and other sensitive institutions, to any individual or organisation is conditional on assurance of confidentiality and obtaining prior consent from the data subject [22]. Also, the bill categorically stipulates that the country receiving transferred data has personal data protection provisions that are at least equivalent to those provided in the bill, and the data so transferred should be processed in accordance with the bill where applicable [22].

The bill provides guidance and follows up action in the event of a personal data breach. The data controller shall, without undue delay where reasonably possible, and within 72 h of a reported personal data breach, notify it to the relevant authority except where the personal data breach is unlikely to result in a risk to the freedom and rights of the data subject [25]. The notification should be in writing, and the incident report should include the nature of the personal data breach, name and contact details of the data protection officer or other contact points where more information can be obtained, likely consequences of the personal data breach, and the measures in placed or proposed to be adopted by the data controller to address the personal data breach [27]. The bill states that anyone found to violate any of the bill's provisions, such as processing, disseminating, or disclosing personal data, shall be prosecuted and incur a fine of up to PKR 15 million [21]. For any subsequent offences, unlawful processing of personal data and sensitive data, the threshold of fines would rise to as high as PKR 25 million [21]. Furthermore, the bill states that anyone failing to adopt the security measures that are necessary to ensure data security and failing to comply with the orders of the personal data protection authority of Pakistan, shall be punished and incur a fine up to PKR 5 million [21].

The summary outlined in the table (See Table 1) suggests that Pakistan provides adequate data protection, in line with GDPR. However, the bill has discrepancies in terms of the need to appoint a Data Protection officer and liability in the form of fines.

India

Informational privacy has won the recognition of the Supreme Court of India and the right to privacy as a fundamental right under the Constitution and has underscored the right to life and personal liberty [29]. This is the first time the Supreme Court has pronounced the right of individuals to their personal data, and privacy and data protection has been placed high on the national agenda as data use is considered a key element in the growth and economic development. However, India is not in par with any convention on the protection of personal data but is a signatory to other international declarations and conventions such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which recognises the right to privacy [30].

The Information Technology Act 2000 governs the protection of personal information, specifically electronic data and transactions [31]. Since 2011, various replicates of the Privacy Bill have been released, and the Data Privacy Bill 2017 is the latest. The draft of the Personal Data Protection Bill (PDPB) 2018 was intended to replace the Data Privacy Bill 2017 and still awaiting approval [32]. As cited, the Indian parliament is expected to vote on the Personal Data Protection Bill of 2019 during the 2020 budget session. On parliamentary approval, India becomes the third-largest entity to implement formal legal frameworks governing the use and share of personal data [33]. The same criteria and standards would apply to all enterprises, including technology companies, e-commerce platforms, real-estate firms and brokers, banking business correspondents, auto dealers, hotels, and restaurants [34].

The Data Protection Bill regulates the use of personal data collected, disclosed, shared, or processed in India, or associated businesses within India, conditional cross-border transfers requiring data fiduciaries to store data in India. The bill also sets out the obligations that would bind all entities processing data to adhere to a host of requirements such as data-minimization, notice-and-consent, transparency, security safeguards and localization [34]. Also, mandatory data breach notification, obtaining prior consent to collect data, and individual privacy rights remain stringent requirements of the bill [31]. These are clearly stipulated as obtaining consent in advance and in writing from the data subject specifying the purpose for which the data would be used before the collection of the data [32]. There is also a provision for collecting sensitive information for lawful purposes connected with a function or purpose of the corporate entity on a necessity basis whilst ensuring that the information so collected was used for the intended purposes only [32]. There is no specific time frame for retaining sensitive personal information [32], but the retention period should not be longer than necessary.

There are also conditional exceptions included in the PDPB, specifically on the processing of personal data for national security, law enforcement, legal proceedings, delivery of medical or health services in emergencies situations and epidemics, provision of assistance during disasters and breakdown of public order, research and archive purposes or where processing is by small entities [34]. PDPB is also applicable to entities outside the territories of India to the extent that the central government may regulate any cross-border data transfers outwards from India. The government has powers to permit such transfers subjected to the provision of an adequate level of personal data protection, adherence to laws and international agreements, and the effectiveness of the enforcement by authorities with appropriate jurisdiction [35].

There is no specific level of penalties set for data security breaches in the current legal framework, and the appointment or role of a data protection officer is not mentioned in the IT rules. However, should the PDPB comes into force, the data fiduciary would be required to appoint a data protection officer and set out his functional roles as specified in the PDPB and the officer's specific functions as deemed necessary [36]. The failure to take appropriate action promptly in response to a data security breach, the data fiduciary shall be liable to a penalty which may extend up to either 2% of its total worldwide turnover in the preceding financial year or Fifty Million Indian Rupees (INR 50 million) whichever is the higher [36]. The same will apply in the case of a data protection officer failing to fulfil his/her responsibilities [36].

The table on Draft Personal Data Protection Bill of India compared with GDPR (See Table 2) infers that the Draft Personal Data Protection bill contains guidelines very similar to GDPR except for the level fines specified in the bill.

Bangladesh

It is only recently legal protection for infringement on personal data has become available in Bangladesh [37], and prior to that, a specific statute was non-existent in the country. Also, data privacy and underlying protection rights and requirements appear to be new concepts. In many instances, the country seems to have been on the verge of facing major threats to privacy and personal data leakage [38]. Therefore, in the absence of a legal framework to curb future challenges of protecting citizens' privacy, the need to develop data protection laws became an imperative priority for the country.

The Information and Communication Technology Act of 2006 (The technology Act) and Digital Security Act addresses issues relating to wrongful disclosure, misuse of personal data, and violation of contractual terms in respect of personal data [39]. The Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act of 2006 has provisions to bring prosecutions against the perpetrators for unauthorised intrusions and access to personal data, but the inherent loopholes allow the offenders to evade prosecution against crimes committed anonymously [38]. Under this Act, those responsible for committing an offence of disclosing confidential and private information could be liable for punitive imprisonments up to two years, with or without a fine extendable up to BDT 200,000 [39].

According to the Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, every citizen shall have the right to privacy in correspondence and other means of communication [40]. In that respect, the basic framework for data protection and privacy sets out the rights of privacy granted under the Constitution of Bangladesh, alongside the Information Communication Technology Act 2006 and the newly enacted Digital Security Act 2018 [39].

The enactment of the Digital Security Act of 2018 has enabled Bangladesh to take a step forward in the right direction into the data or information protection regime. Its purpose is primarily to promote confidentiality, integrity, and availability of public and private information systems and networks and, also, to protect the rights of individuals and privacy, economic interests, and security in cyberspace [41]. This Act explicitly requires obtaining consent or authorisation from data subjects before collecting, storing, and processing personal information [41]. However, Bangladesh recognises that implementing GDPR mandated requirements for data protection officers, data protection impact assessments and audits, breach notifications, and record-keeping would prove to be difficult and costly for many small companies in Bangladesh [42]. The rules specify that anyone attempting to illegally access a computer or digital system and to interfere by making changes, transferring any data or information owned by any organisation, will be legally liable for committing a punishable offence, in the form of imprisonment not exceeding five years and/or a fine not exceeding BDT 1 million [39].

In Bangladesh, the proposed Digital Security Act sets out provisions very similar to GDPR (See Table 3). However, despite the close alignment, differences exist in terms of the requirement to appoint a data protection officer and to issue a data breach notification.

Bhutan

The privacy issues in Bhutan have not been sufficiently articulated in the literature, policies, or guidelines. However, the reports suggest that seven of the ten second-generation principles in the 1995 EU Data Protection Directive have been included in Bhutan's Information, Communications and Media Act, which came into force in 2018, but with limited coverage on privacy and privacy law [6]. Also, the Social Media Strategy and Guideline Policy of Bhutan (2011), the Information and Communications Technology Policy and Strategies (2004), and Bhutan e-Government Master Plan (2014) have limited emphasis on privacy issues [43]. Thus, these acts are considered only moderately strong for the Asian region. As such, non-EU businesses are losing European Partnership contracts because adequate protection of data in compliance with GDPR could not be guaranteed. Yet not all businesses or government organisations in Bhutan had been affected by GDPR simply because either the businesses in Bhutan do not have commercial links with European companies, or they do not require access to the personal data of EU citizens.

Nepal

Nepal's laws evidently contain a comprehensive set of regulatory features relevant to personal data that could be expected in a data privacy Act for the public sector. These are clearly specified as the right of access; right of correction; protection against unauthorised access; restrictions on the use and disclosure by government agencies; limitations on additional usage by third parties when obtaining access; both offences and compensation provisions for breaches; an independent authority to investigate complaints and resolve disputes; and a right of appeal to the courts.

The right to privacy as a fundamental right featured for the first time in the 1990 constitution of the Kingdom of Nepal, and so did the right to information, and later, the right to privacy was retained in the 2007 interim constitution [44]. However, there was no reference made to the authority of the state to receive violations of privacy rights complaints, but the public had the freedom to submit such reports to the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), and also the option to take legal action against violation of the right to privacy, in the Nepalese courts [44].

Nepal became the Federal Republic in 2015 with the promulgation of the new Constitution, and substantial changes were made to the country’s legal system [45]. The critical element is the right to privacy and protection of information as a fundamental right stipulated in Article 28 of the Constitution, along with that constituted the criminal code and the Individual Privacy Act 2018 [46]. The Criminal Code has a separate chapter on laws covering privacy violations, breaches of confidentiality, taking and editing photos of a person without consent, and breaches of private information in electronic media considered criminal acts [47].

Nepal enacted the Privacy Act of 2018 [48], but notably, it was not considered a data privacy law due to the exclusion of basic principles. However, private sector bodies operating in Nepal were obliged to pay careful attention to many provisions in the Act. For example, personal data collected by corporate entities might only be used for the purpose for which such data was collected, and collection and disclosure were prohibited without consent [48]. That is an endorsement of the need to obtain consent before collecting private information and the restrictions on collecting data and using it only for the purposes for which it was collected.

These obligatory requirements generate more responsibility on businesses as commercial activities conducted online need to collect the users' personal data and restrict data sharing with third parties. However, in terms of collecting or using personal information belonging to a Nepalese resident from outside the territory of Nepal or involving an offshore entity within Nepal, the enforcement of the Act appears vague [49]. Therefore, the purpose for collecting data and information and the intended use should be revealed with clarity. If the intention behind information gathering is for a particular need, academic study, specific research objectives, public opinion, then the nature of the collection, the purpose for the collection, methodology and mode of information processing, along with assurance not to breach the privacy of individual information must be presented.

The Act requires public authorities or corporate bodies to obtain consent from the individual/s before disclosing personal information collected, stored, or retained by them [46]. The violation of the Act is a criminal offence, and legal action commensurate with the offence may be taken by either an individual or the State, and proven liable, the offender would incur imprisonment of up to 3 years or a fine of up to NPR 30,000 or both. Also, the offender could be liable to pay compensation to the affected party (victim) for the violation of the provisions of the Act [46].

The Privacy Act, however, has failed to address the shortcomings and important aspects in it. The existing definition does limit broader interpretation of 'personal data.' Another important shortcoming is that the Privacy Act does not define or specify some of the vital concepts of data protection such as 'controller' and 'processor.' This will make data management difficult and in practice, will hamper legal enforcement of punitive action against breaches in Nepal (Table 4).

Afghanistan

The use of information and communication technologies in Afghanistan has been growing rapidly [50], and the popularity of modern technology has made its way into all aspects of the citizens making a difference to their way of life. In the absence of specific laws or regulations to manage data protection in Afghanistan [51], it is important to put in place legal frameworks that will safeguard private and enterprise data flowing through the ICT based infrastructures. The Constitution of Afghanistan guarantees the right of confidentiality and privacy to its citizens using a broad spectrum of communications systems [51]. It provides freedom and confidentiality of correspondence between individuals by way of a letter, telephone, telegraph, as well as other means [51]. Some laws do address other aspects containing data protection provisions, but there is also a need to develop regulations to implement the privacy Laws.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka has a growing population, and the use of information technology and associated services is growing even at a faster rate [52], so is the use of cyberspace. A vast majority of the population use mobile phones to manage their daily lives, and amongst them, a new generation of professionals, youth, and those still in education are resorting to modern technology and associated IT systems using online network facilities available right across the country [52]. This trend will continue in a progressively developing country becoming increasingly dependent on advanced technology and the benefits it offers to the citizens.

That is all well and good. The concerning factor on the consumer front is the inevitable intrusion into the privacy of the users of information and technology and modern digital systems. That exposes the users, and there is a pressing need to develop laws to safeguard against the challenges of cyberspace crime faced by the state and the users. The most important of them is to legally protect individuals' personal information, which cannot be ignored or treated mildly. In forming legislation, the parameters of the importance of the law and the guideline should be considered to ensure they are sound, unambiguous, and enforceable.

On the economic front, Sri Lanka needs data protection and information security laws as they are crucial to attracting foreign direct investment (FDI), and as pointed out by the economists, due to the lack of adequate legal mechanisms, the foreign investors will be reluctant to invest in the country [53]. In a different context, however, Sri Lankan entities that process data of European residents are faced with stringent obligations. The Computer Crimes Act 2007 appeared to have addressed the issue of data privacy to some extent by specifying penalty clauses for unlawful acquisition and illegal interception of data and unauthorised disclosure of information [54]. Also, the right to privacy has been recognised by the judiciary under the common law of Sri Lanka [54]. This indicates that despite the absence of specific constitutional or legislative recognition, the right to privacy recognises the Sri Lankan judiciary in a variety of legal contexts under common law.

Chapter III of the Sri Lanka Constitution (1978) provided adequate guarantees for the fundamental rights of its citizens, but not specifically for the right to their privacy [55]. The proposed versions of the drafts of the Constitution in 1997 and 2000 had stipulated the right to privacy and family life as a fundamental right [55]. The proposed October 1997 Constitution specifically stated every person has the right to have his or her private and family life, home, correspondence and communications respected and shall not be subjected to unlawful attacks on his or her honour and reputation [55].

The 19th Amendment to the Constitution makes minimal, half-baked reference to privacy. It states that a fundamental right to information cannot be complied with if an individual's privacy is to be tampered with [9]. This was not an expressed provision where the right to privacy was a separate and compounded fundamental right of the citizens in Sri Lanka, and if this right was to be exercised against private organisations, it should be separately encapsulated in the statute. To remove any ambiguity in the reference made to the constitutional right of privacy, the Minister for Telecommunications had confirmed that a Personal Data Protection Bill would be introduced in Parliament in 2019 [56]. The Data Protection Drafting Committee of the Ministry of Digital Infrastructure and Information Technology (MDIIT), and the Legal Draftsman Department, have initiated drafting legislation on data protection [57]. The drafted bill aims to cover the fundamental principles of privacy and data protection, shadowing legislation models introduced by similar countries.

The bill prescribes measures to protect the personal data of individuals held by banks, telecom operators, hospitals, and other entities amalgamating in processing personal data [57]. It aims to regulate the processing of personal data, designate a data protection authority, and safeguard the rights of citizens [58]. Under the terms of the bill, data could be processed for specified purposes only, with a provision that the data could be processed for purposes in the public interest, to respond to an emergency, and for scientific, historical, research, or statistical purposes [58]

The rights of data subjects provided in the bill include the right to withdraw the consent given to controllers, the right to access, rectify, and erase data without undue delay, and to object to the processing of data [58]. Consent is now required before collecting private information, and even if consent is obtained, the collected data should only be used for the purposes for which it was collected [58]. The final draft stipulates that every controller, unless exempted from this Act or any written law, is obliged to appoint a Data Protection Officer to ensure compliance [58]. The data protection authority shall be responsible for all matters relating to personal data protection in Sri Lanka and for the implementation of the provisions of the bill. The penalties for failure to comply with the provisions of the bill shall not exceed a sum of LKR 10,000,000 in any given case [57].

The bill stipulates that only public authorities may process personal data within Sri Lanka, and the processing of classified data overseas is subject to permission being granted by the DPA and any relevant supervisory body [6]. The private sector is not subjected to conditional data localisation stipulations except for transferring personal data to a third country prescribed by the Ministers [6].

The Framework for the Proposed Personal Data Protection Bill was first released on 12 June 2019 for stakeholder comments, and the final draft was released on 24 September 2019 by the Ministry of Digital Infrastructure and Information Technology [53]. The bill comprehensively covered both the public and the private sector in full. The legislation was to be implemented in stages, and the bill was scheduled to become operational within a period of 3 years after ratification by the Parliament, allowing the Government and private sector a time-lapse to prepare for the implementation of legislation [53].

Sri Lanka deserves credit for its commitment to developing a data protection mechanism, despite its developing country status. The summarised information in the table (see Table 5) shows draft legal mechanisms compared to GDPR.

Maldives

The criteria for data protection in the Maldives fall under the right to privacy, and it was embedded in the 2008 Constitution of the Republic of the Maldives and the Penal code of the state [59]. The penal code prohibits obtaining private information or highly secured information without having a license or authority to do so and disclosing any such information to a third party [59, 60].

In 2016, the Ministry of Economic Development of the Government of Maldives announced the drafting of a new data protection bill and was circulated to the public, but it has not yet become law [59]. The purpose of the Act was to promote small and medium enterprises, encourage e-commerce, and establish procedures to store, manage, and protect customers' confidential information [61]. The apparent shortcoming of the Act was the absence of one important element: the provision to punish non-compliance but has made allowance for everyone the use of discretion to comply with the Act [61]. The primary beneficiary of the Act is identified as the commercial sector as they need an efficient system to manage, use and store confidential information in accordance with international standards and thereby boost customer confidence in the enterprises [61].

This analysis of the South Asia region shows that some countries appear to have no mechanisms of any kind; however, those having at least a draft mode of data protection mechanism intends to develop legal mechanisms matching GDPR. Given these positive trends at national level, it is optimistically conceivable that the SAARC regions would maintain a constructive dialogue between the nations, consolidate its influence in the region to move forward with a consensus-based approach to develop a regional level data protection mechanism, and sustain the momentum ultimately to achieve the goal of developing a global level data protection mechanism.

Research Methodology

This research is qualitative in nature, and it enables the researcher to get a deeper understanding of experiences, phenomena, and context [62]. Qualitative research is a stimulant to ask questions by way of observations, in-depth interviews, focus groups, and existing documents, paper surveys with open-ended questions and online surveys, and it produces subjective knowledge [63]. The characteristics of the qualitative data collection method fit in well with the aim of the research. The researcher decided to use the qualitative data collection method to get an in-depth understanding of the available data protection mechanisms and the challenges and the barriers faced by the countries in the South Asian region. To that end, in this research, the researcher used journals, books, newspapers, websites, government reports, and constitutions for collecting data for this research and found books and journals excellent sources for extracting background information that contributed to widening the scope of the study. The main data sources used in the literature review are the Government Websites, Publications from companies, Google Scholar and Researchgate. Several keyword searches were used to find the studies relevant to answer the research questions.

The aim of the Qualitative studies is to gain a greater level of understanding of the subject [64]. This approach specifically answers the questions such as ‘how’ and ‘Why’. Therefore, the use of qualitative analysis in this research has enabled the researcher to analyse the findings and provide detailed answers to the research question. To that end, the qualitative analysis was used mainly to obtain answers to the questions such as why it is important to develop data protection mechanisms and what type of challenges the countries would face in developing GDPR inspired data protection mechanisms. The researcher used government websites to access data protection mechanisms relevant legal documents, understand the existing ones and ascertain the differences between them. The newspapers provided contemporary data about the new changes incorporated into existing legal mechanisms. Considering the findings, the researcher critically analysed the important parameters identified in the literature review.

The main limitation of this research is that the literature search pointed to contradicting information on data privacy and security policies, and it was a challenge that affected the progress of the literature review. An unknown number of countries are in the process of reviewing and modernising their legal mechanisms to protect personal privacy in the climate of evolving technologies. That, in a way, has inundated literature published in the previous years. It was a matter of selecting the most appropriate articles to ensure the quality of the research outputs.

Discussion

Similarities and Disparities Between GDPR Inspired Bills in South Asian Countries

The states and state apparat, organisations and individuals face sophisticated, complex cyber-security threats designed to cause significant damage to the economy and infrastructure dependent essential services. This has become a frequent occurrence especially in the countries in the Asia region where, unlike those in the West, the use of the internet has expanded at a rate in correlation with the internet revolution. That has invariably aroused growing concerns in the community about cybercrimes ranging from data breaches to transferring personal data. To allay any concerns and fears, most Asian countries have taken steps to introduce new data protection legislation or enhance existing cybercrime countermeasures.

The South Asian region has no regional level data protection mechanism in place yet, but having one will encourage them to develop a global level data protection mechanism. To reach that point, it is important to identify the ambiguities in GDPR inspired bills already possessed by the countries in this region. The understanding of discrepancies would help to resolve implicit issues between the countries and bring them together to establish a common stance on developing a unified regional level data protection mechanism that would eventually level up towards developing a global level data protection mechanism.

The commercial sector in the South Asian region is growing in line with modern technology and increasingly becoming digitalised and moving into online platforms to conduct business activities [56]. In the light of these changing environments, the public, private, and non-profit entities are all in the process of introducing Information and Communication Technology (ICT) to improve their computing capabilities, in a continuous process to keep up with the Western world. The number of ICT users is growing at an unprecedented rate, and they are constantly becoming attracted to ICT capabilities, but many in general lack technical knowledge of cyber security and their privacy rights [65]. That exposes commercial enterprises and individual users to greater risks from cyber-attacks originating from locations anywhere in the world. Therefore, it is imperative for both the private sector and the individual users of cyberspace to have sufficient awareness of their exposure to the risks from cyber threats and their privacy rights. However, South Asian countries are facing a daunting task of having to strike a balance between privacy and the right to information. The lack of awareness itself is only one of many factors such as language barriers, limited education, lack of opportunities, and many do not have access to the high-tech environment. Also, many users are not aware of the cyber laws their government has put in place, and there is more to be done to make such information available to the citizens to raise awareness of the consequences of cyberspace crime.

The rise in data breaches and privacy-related incidents has facilitated discussion around how much control people should have over their personal information. Since then, there has been improved recognition of the right to privacy in the digital age and increased awareness amongst the public regarding how individuals can access or control their data. On another positive note, there has been a push for comprehensive rights for the individuals, such as the right to request consent for processing and the right to be forgotten; governments have responded by strengthening their privacy law frameworks. In addition, the organisations, when collecting personal information and when processing and transferring personal information to a third party are required to seek consent from the individuals. The organisations engaged in processing personal data are also required to employ a data protection officer within the organisation.

At the global level, the rise in data breaches in terms of frequency and volume has put pressure on governments to introduce data breach notification requirements making reporting of data security breaches mandatory. The notification should include complete details of the breach, the name and contact details of the data protection officer, a description of the likely consequences of the breach and an incident recovery plan proposal for mitigating its effects. Those organisations violating the rules will become liable and incur a heavy fine.

Since the GDPR came into effect, many commercial enterprises became obliged to re-examine their stand on privacy rights. The European Commission enabled the free flow of data between the EU and countries considered to have ‘adequate’ regulations in place. Many are currently seeking to strengthen their laws to obtain adequacy in the South Asian region (Table 6).

There is a visible lack of literature on national level GDPR inspired data protection mechanisms and adequacy of those mechanisms to GDPR in the South Asian region. Therefore, the discussion in this paper would contribute to the prevailing knowledge and help future researchers in their research surrounding regional level data protection mechanisms in the South Asian region. In the absence of a regional level mechanism in the South Asian region, the findings presented in this paper would serve as a valuable source to future researchers and would help them to foresee the progress of the development of a regional level mechanism.

Barriers to Developing Data Protection Mechanisms

The apparent hesitancy and reluctance of South Asian states to participate, and the prevalence of external/internal issues affecting collective decision making seem contributory factors hindering progress towards the development of cyber specific regional level mechanism.

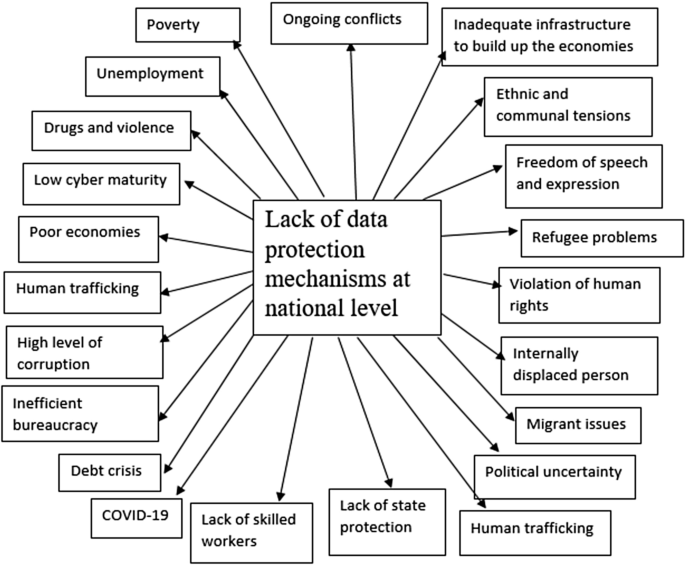

Social Differences

The assessment of social impacts is essential to determine what difference a policy will make to people’s lives. It enables the researcher to analyse the social impacts and consider the widest range of impacts that policies would have on individuals, communities, and society. A summary of social differences within the countries is outlined in Fig. 1.

Many of the wealthiest countries record the highest current-level development scores, and they enjoy political stability, freedom of expression, and low levels of corruption [66], and that allows the countries in this category space to focus more on developing data protection mechanisms in comparison to less developed countries that are struggling to reconcile the differences exist in them.

A country’s overall economic strength influences internet diffusion and the resources and capital required to expand technology [67], and there is also a demand for capital investment for developing data protection mechanisms. Therefore, the economic stability of the developed countries have the capacity to allocate funding towards the protection of privacy of their citizens and assist in reviewing existing policies of the developing/underdeveloped countries.

The knowledge of the individuals also may influence the spread of communication technology [67]. The knowledge is of many forms ranging from knowledge of the use of communication technology to privacy and security threats associated with technologies. This knowledge gives users an insight into technology and understands the necessity of having established data protection mechanisms. In addition, the literature suggests that some languages have greater recognition than others, and they dominate certain areas of life, for example, the use of the English language in the computer industry [67]; hence the language barrier could be an obstacle to developing policies. Therefore, literature material should be translated into multilingual formats and made easily available and accessible to all countries for developing data protection mechanisms.

Furthermore, the cultural background also can contribute to the development of data protection mechanisms. In Asia, the interpretation of the perception of obscenity and pornography/erotica varies from country to country [68]. For example, the reports suggest that Japanese people have a higher tolerance to erotic materials, in comparison to those in China, Taiwan and Hong Kong [68]. The reports suggest that the Islamic countries also have a lesser tolerant approach to obscene materials. Hence, the countries such as China, Singapore, Pakistan scrutinise social networking sites or even block web access to filter out such sensitive material [68]. These social differences and beliefs form the most significant barriers to developing a global level data protection mechanism.

These social differences and beliefs are the biggest barriers facing developing a global level data protection mechanism. However, a report suggests that an increasing number of Europeans living in the border regions of the EU claims social and economic differences are not the problem acting cooperation between their home and neighbouring country [69].

Mistrust Between Countries

The emerged mistrust amongst the countries has come about for a variety of reasons, such as political differences, border disputes, and the persistence of ongoing conflicts. As an example, the tensions arising from the border disputes between India and Pakistan, for instance, is an example of why the countries embroiled in conflicts find it difficult to come together for the common good [70]. The ongoing conflict between Nepal and India involving a section of the Madheshi community in Nepal led to the closure of the India–Nepal border in 2015, and given the socio-cultural proximity of the Madheshi community with India, the blockade impacted on bilateral ties between the two nations [70]. These reasons have become a challenge in bringing everyone together to come up with a global level data protection mechanism.

Legal Differences

The ways in the countries adhere to international or regional conventions differ between the countries, and these differences tend to influence the determination of specific initiatives to develop their laws. Legal disparities make it difficult to respond and investigate, enforce the law, and hinder international collaboration [71]

Internet Penetration

The reports produced by the World Bank highlight marked differences between the South Asian countries in terms of internet penetrations, and amongst them, Bangladesh (58.4%) has the highest internet penetration, and Pakistan (32.4%) has the lowest internet penetration [72]. These variations in the level of internet penetration demand countries to increase financial resources take prompt actions to protect the privacy of their citizens.

Identification of Difficulties

One of the most concerning and significant is the attribution hindrance [73]. The perpetrators are becoming increasingly effective in concealing the authenticity of identities, and their operational locations and, also the identification of the origin of a cyberattack is extremely difficult, even impossible, without international cooperation. Furthermore, the limitations in jurisdiction make investigation a complex process and a challenging task that makes prosecution of cyber perpetrators a futile effort.

Delays in the Enactment of Laws

The enactment law/s in different countries is driven by the decisions made at the national level, based on various factors in different circumstances. They could be political, economic, and social issues. For example, the ratification of the Budapest Convention had taken too long by most countries for varying reasons; the delayed development of the law is one of them [71]. In another scenario, UN negotiations of a new treaty on cybercrime will take an intense diplomatic effort lasting a considerable timescale without achieving a successful outcome [74].

Laws and Basic Principles Overlap

The internet has no physical borders and is freely available to the users, governed by national legislation, but constitutional or legal conflicts can arise on the grounds of privacy and freedom of expression. This could lead to debatable contentious privacy and security issues, which may drag on unabated with no end to it.

Differences in National Legislation

There are apparent differences between national legislations of countries. For example, the defined expression of a data breach and the time limit for notifying the breach to the individuals and/or the authorities varies significantly [75]. In the EU, a data access breach alone, however minor, makes it a notifiable breach within 72 h of being detected, in most cases [76]. In China, the discovery of security flaws and vulnerabilities in network products and services necessitates informing the relevant government agencies and network users of such breaches [77]. In Japan, the only requirement is to ‘make the effort’ to notify the incident of a breach [78], even that requirement is deemed a vague one.

When it comes to the South Asian region, according to Pakistan, the data controller should notify the data breaches to the relevant authority within 72 h of the known incident, except when breaches are unlikely to affect the freedom and rights of the data subject [27]. In India, Data breach notification is mandatory, but the time duration has not been specified [36]. In Bangladesh, no reference is made to this requirement for data breach notification [42]. Likewise, even though South Asian countries developed GDPR inspired bills, some differences between countries exist.

The reliance on new technologies and IoT generates a large volume of information, and any data breach will impact personal privacy, and to safeguard privacy, it is important to have data protection mechanisms. To meet that requirement, most countries revisited and developed data protection mechanisms at the national level lining with GDPR. However, some countries are yet to make up ground. Also, there is a necessity for developing a regional and global level mechanism to bring perpetrators to account. Therefore, it is essential to identify the challenges faced by countries when developing such mechanisms.

There is little insufficient literature on the identification of the barriers to developing unified data protection mechanisms. Therefore, the barriers and the challenges listed in the research paper would contribute to existing literature and would benefit future researchers seeking to develop a unified data protection mechanism. It is important to bring all the countries together to develop a unified data protection mechanism, but it is easier said than done. Therefore, to reap the benefits of collaboration, it is important to identify and address the disparities and support those in need by sharing know-how from those conversant with policy development.

Conclusion

In the light of increased reliance on technologies, the world is faced with unprecedented challenges from cybercriminals. The reality of increasing cyber-related threats became a major concern for the intelligence and security services and, in the wake of cyberthreats spreading beyond borders, the need to find solutions became a high priority. The higher risk factors to the privacy of the individuals inevitably brought to the forefront the need to find solutions to the challenges faced by the organisations and the security services. The cyberspace related threats are stealth in nature, and the enemy is characteristically invisible, difficult to trace, and dangerous, and that made taking urgent action to protect people and the nations a necessity. Against that background, the need to develop a global level policy framework to fill the gaps in the existing legislation became an urgent necessity. Therefore, in this research, the researcher selected South Asian region and sought to explore existing data protection mechanisms and identified the challenges and barriers they faced in developing data protection mechanisms. The intended purpose of the identification of the barriers is to influence and encourage those countries to develop a unified mechanism that would serve the interest of all.

The available literature suggests that most countries in the South Asian region possess at least a draft data protection mechanism in place at the national level. Some are in the process of implantation of appropriate legislations that are designed to deter unethical activities with some success, but those countries without adequate data protection and privacy acts have failed to successfully prosecute cyber-criminals for violating legislation. The analysis of this research showed that, except for the differences in the requirement to appoint a data protection officer and the amount of the imposable fine, the GDPR inspired bills provided an adequate level of data protection to citizens in the South Asian region. The discussion on the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) suggests that it remains the only credible source of guidance, and there is no visible collective approach to developing robust unified data protection mechanisms at the regional level. These findings answer the research questions which sought to identify the GDPR inspired data protection mechanisms in the South Asian region and their adequacy to GDPR. The researcher believes that it is essential to have unified purposeful data protection mechanisms developed collectively by the nations to overcome security and privacy challenges and prevent data breach perpetrators escape with impunity. In pursuit of that aim, it is important to identify the factors that affect progress to developing data protection mechanisms.

The literature-based evidence shows that there is a general disparity in the privacy policy and data protection legislation amongst states, but when looked separately at the national and regional levels, the degree of disparity varies. These disparities are attributable to several internal and external factors and are influenced by specific laws of the states. It is also important to identify the gaps in cyber legislation that allows cybercriminals to get away without impunity for the weaknesses in law enforcement and inconsistency in the laws themselves. The identification of these challenges and barriers meet fulfilment of the research question aimed to ascertain the barriers the countries faced in the process of developing data protection mechanisms. These identified gaps/limitations/disparities in the regulatory frameworks, when scrutinised in real situations, make a case for having a unified global level privacy policy and strategic data protection laws to prevent states and organisations from taking arbitrary actions and to avoid perpetrators walking away without any proper punishments for the actions. All that said, there is an exception to the rule, ‘national security’ of the state overrides any emphasis on privacy protection, but it has essentially to be on a need basis.

The absence of a collectively established universal data protection mechanism indicates a clear gap at the global level. It is fair to say that the lack of data protection mechanisms at the national level is hindering and slowing down the progress in developing regional data protection mechanisms. To overcome this, respective countries need to revisit and develop their national-level data protection mechanisms. Having proper mechanisms in place at the national level will make it easier to facilitate a constructive dialogue to produce a meaningful unified regional mechanism. Currently, most nations have individually developed data protection mechanisms matching GDPR, which sets the benchmark for the other nations. In the negotiating process, the diplomatic route would be the preferable option to influence and urge the countries to take collaborative, cohesive action in a participatory manner. That would give each nation the opportunity to open discussion and express their views, resolve any misgivings, and an added impetus to developing a consensus-based data protection mechanism. The failure to do so is likely to jeopardise the chances of ratification and implementation.

The existing literature comprises data protection mechanisms in the South Asia region, but the existing literature does not demonstrate variations between the GDPR inspired bills in that region and the EU GDPR. Therefore, the researcher’s findings on the adequacy/inadequacy of the GDPR inspired bills in the South Asian region adds new knowledge to the current literature. In addition, the literature readings indicated that whilst some countries in the South Asian region were in the process of drafting their national-level data protection mechanisms in parallel to the GDPR, some countries failed to keep up. Therefore, to understand the barriers countries faced in developing data protection mechanisms, the researcher conducted a thorough literature review, the outcome of which would also contribute to existing literature. It would be beneficial to have necessary mechanisms in place to overcome those challenges and bring countries together to develop an unified data protection mechanism.

The future researchers undertaking research to find common factors that would bring all the countries together to develop a unified data protection mechanism would also benefit from this research findings/study. The identification of the barriers to begin with would help them in their research to address these barriers and support to overcome them. That would help in developing a lasting sustainable unified data protection mechanism fulfilling the interest of all the countries.

Recommendations

The researcher recommends that the SAARC should support South Asian countries to take the initiative to develop national and regional level data protection mechanisms. To make it happen, the SAARC should take the initiative to make awareness of the importance of protecting personal data and should provide appropriate guidance and support. The recommendation is to set up a project team consisting of like-minded professionals with expertise in negotiating and influencing those at the highest level in governments, the judiciary, and policy development, preferably facilitated by the SAARC. The team must have clear terms of reference and delegated authority to seek assurances from the governments to expose and share their plans for developing legislation on data security and privacy protection laws. Realistically, it may not be easy in the absence of consensus amongst the nations across the region, and whilst they remain engrossed in their uncompromising ideology and their stand on statehood as world leaders. These attitudes will have to be overcome if world order means anything, and it would be a daunting task to set a time scale to achieve the outcome as the process itself is likely to be an evolving one, and the success is dependent on good faith and willingness of the countries to play their part in the interest of the global community.

References

Dhungel, R. Cyber Security For National Security. 2019. https://risingnepaldaily.com/opinion/cyber-security-for-national-security. Accessed 12 Apr 2020.

Hollis, D. A brief primer on international law and cyberspace. Carnegie endowment for international peace [Online], p.3-4. 2021. Available at https://carnegieendowment.org/files/Hollis_Law_and_Cyberspace.pdfhttps://carnegieendowment.org/files/Hollis_Law_and_Cyberspace.pdf. Accessed: 13 July 2021.

European Union. Legislative acts. Official Journal of the European Union [Online], p.88. 2016. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679. Accessed 15 Feb 2019.

Burgess, M. What is GDPR? The summary guide to GDPR compliance in the UK. 2020 https://www.wired.co.uk/article/what-is-gdpr-uk-eu-legislation-compliance-summary-fines-2018. Accessed 20 May 2020.

Raghunath P. Human security in a datafying South Asia: approaching data protection. Int J Med Stud. 2019. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3438583.

Greenleaf, G. Advances in South Asian data privacy laws: Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Nepal. Privacy Laws and Business International Report. 2019. file:///C:/Users/sm77809/Downloads/SSRN-id3549055.pdf. Accessed 2 Jan 2020.

Greenleaf, G W. Asian Data Privacy Laws: trade and human rights perspectives. First edition. Google book. 2014. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=3yfSBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA438&lpg=PA438&dq=data+privacy+and+security+policies+in+nepal&source=bl&ots=HJCoGnm1xK&sig=ACfU3U2iMecNAbiaFx4aGdgMXh2OxAVk0Q&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjQrqKKzr7qAhXUnFwKHVq_DSk4ChDoATAFegQIChAB#v=onepage&q=data%20privacy%20and%20security%20policies%20in%20nepal&f=false. Accessed 15 Apr 2018.

De Soysa, S. The right to privacy and a data protection act: Need of the hour. 2017. http://www.ft.lk/article/606874/The-right-to-privacy-and-a-data-protection-act:-Need-of-the-hour. Accessed 23 Feb 2018.

UNCTAD. Data protection and privacy legislation worldwide [Online]. 2020. Available at https://unctad.org/page/data-protection-and-privacy-legislation-worldwide. Accessed: 15 June 2021.

Tovi MD, Muthama MN. Addressing the challenges of data protection in developing countries. Eur J Comput Sci Inf Technol 2013;1(2):5 [Online]. Available at: https://www.eajournals.org/wp-content/uploads/ADDRESSING-THE-CHALLENGES-OF-DATA-PROTECTION-IN-DEVELOPING-COUNTRIES.pdf. Accessed 18 Nov 2019.

Government of UK. National Cyber Security Strategy 2016-2021. Government of UK [Online], p.63-64. 2016. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/567242/national_cyber_security_strategy_2016.pdf. Accessed 5 Sept 2019.

Wolford B. What is GDPR, the EU’s new data protection law? 2022. https://gdpr.eu/what-is-gdpr/. Accessed 22 Nov 2020.

ICO. The principles. 2022. https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-data-protection/guide-to-the-general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr/principles/. Accessed 13 Mar 2018.

ICO. Guide to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/711097/guide-to-the-general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr-1-0.pdf. Accessed: 14 Feb 2019.

GDPR.eu project. What are the GDPR Fines?. ND. https://gdpr.eu/fines/. Accessed 15 Aug 2018.

Albrecht JP. How the GDPR will change the world. Eur Data Prot Law Rev. 2016;2:3. https://doi.org/10.21552/EDPL/2016/3/4.

Government of UK. The Queen’s speech 2017. Prime minister’s office, London. 2017. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/620838/Queens_speech_2017_background_notes.pdf. Accessed 05 Jan 2020.

Greenleaf, G. Privacy in South Asian (SAARC) States: reasons for optimism, UNSW Law Research Paper No. 18–20. 2017. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3113158. Accessed 15 March 2018.

OneTrust Technology. Pakistan: Revised draft Personal Data Protection Bill v. GDPR. 2019. https://www.dataguidance.com/opinion/pakistan-revised-draft-personal-data-protection-bill-v-gdpr. Accessed 3 July 2019.

Privacy International and the Digital Rights Foundation. State of privacy Pakistan. 2019. https://privacyinternational.org/state-privacy/1008/state-privacy-pakistan. Accessed 20 Feb 2020.

Rehman, S. Pakistan-data protection overview. 2020. https://www.dataguidance.com/notes/pakistan-data-protection-overview. Accessed 23 August 2020.

OneTrust Company News. What is the Pakistan data protection bill 2018?. 2018. https://www.onetrust.com/what-is-the-pakistan-data-protection-bill-2018/. Accessed 4 November 2018.

IFEX. Pakistan’s new draft of data protection law contains ‘draconian and anti-democratic’ sections. 2020. https://ifex.org/pakistans-new-draft-of-data-protection-law-contains-draconian-and-anti-democratic-sections/. Accessed 10 July 2020.

DLA Piper. Data protection laws of the world. 2020. https://www.dlapiperdataprotection.com/index.html?t=transfer&c=PK. Accessed 3 Jan 2021.

The global legal group. Pakistan: Data Protection Laws and Regulations 2020. 2020. https://iclg.com/practice-areas/data-protection-laws-and-regulations/pakistan. Accessed 13 Oct 2020.

Panakal, D. D. Pakistan’s data protection bill includes localization and registration provisions. 2020. https://www.natlawreview.com/article/pakistan-s-data-protection-bill-includes-localization-and-registration-provisions. Accessed 5 July 2020.

Government of Pakistan. Personal data protection bill. 2018. https://moitt.gov.pk/SiteImage/Downloads/Personal%20Data%20Protection%20Bill%20without%20track%20changes.pdf. Accessed 10 January 2019.

Intersoft Cosulting. General data protection regulation. 2022. https://gdpr-info.eu/chapter-1/. Accessed 22 March 2019.

Jyoti P. India's Supreme Court upholds right to privacy as a fundamental right—and it's about time. 2018. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2017/08/indias-supreme-court-upholds-right-privacy-fundamental-right-and-its-about-time#:~:text=The%20one%2Dpage%20order%20signed,Part%20III%20of%20the%20Constitution Accessed 10 Aug 2018

Talwar Thakore and Associates. Data Protected–India. 2020. https://www.linklaters.com/en/insights/data-protected/data-protected---india#:~:text=India%20is%20not%20a%20party,or%20the%20Data%20Protection%20Directive.&text=India%20has%20also%20not%20yet%20enacted%20specific%20legislation%20on%20data%20protection. Accessed 20 June 2020.

Deloitte. The Asia Pacific Privacy Guide. 2019. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/in/Documents/risk/in-ra-Deloitte_AP-PrivacyGuide_Interactive-noexp.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec 2019.

Subramaniam A, Das S. The Privacy, Data Protection and Cybersecurity Law Review: India. 2020. https://thelawreviews.co.uk/edition/1001546/the-privacy-data-protection-and-cybersecurity-law-review-edition-7. Accessed 14 Oct 2020.

Cloen, T. South Asia: The road ahead in 2020. 2020 https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/commentary/feature/south-asia-the-road-ahead-in-2020/#India. Accessed 12 May 2020.

Burman, A. Privacy and Promote Growth. 2020. https://carnegieindia.org/2020/03/09/will-india-s-proposed-data-protection-law-protect-privacy-and-promote-growth-pub-81217 Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Deloitte. India draft personal data protection bill, 2018 and EU General Data Protection Regulation a comparative view. 2019. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/in/Documents/risk/in-ra-india-draft-personal-data-protection-bill-noexp.pdf. Accessed 20 Sept 2020.

Walia H, Chakraborty S. India: Data protection laws and regulations 2020. 2020. https://iclg.com/practice-areas/data-protection-laws-and-regulations/india. Accessed 10 November 2020.

Moniruzzaman M. Personal data protection in Bangladesh and GDPR. 2019. https://bdjls.org/personal-data-protection-in-bangladesh/. Accessed 23 Sep 2020.

Hossain K, Alam K, Khan SU. Data privacy in Bangladesh a review of three key stakeholders perspectives. 2018. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329275065_Data_Privacy_in_Bangladesh_A_Review_of_Three_Key_Stakeholders_Perspectives. Accessed 12 Dec 2018.

Doulah N. Bangladesh-data protection overview. 2020. https://www.dataguidance.com/notes/bangladesh-data-protection-overvie. Accessed 3 Oct 2020.

Molla, M. S. and Nahar, S. Need of Personal Data Protection Laws in Bangladesh: A legal Appraisal. ND. https://www.hg.org/legal-articles/need-of-personal-data-protection-laws-in-bangladesh-a-legal-appraisal-48450. Accessed: 12 February 2020.

Mishbah ABMH. Bangladesh steps into the data protection regime. 2019. https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/human-rights/news/bangladesh-steps-the-data-protection-regime-1726351. Accessed 22 May 2018.

Goswami S. Bangladesh to propose a privacy law. 2021. https://www.bankinfosecurity.asia/bangladesh-to-propose-privacy-law-a-15898. Accessed 3 Mar 2021.

Author unknown. Digital privacy: issues and challenges in Bhutan. 2015. https://kuenselonline.com/digital-privacy-issues-and-challenges-in-bhutan/. Accessed 23 Jan 2018.

Pradhan K. Nepal. 2014. https://www.giswatch.org/en/country-report/communications-surveillance/nepal. Accessed 24 Feb 2018.

National Forum of Parliamentarians on Population and Development. Nepal's Constitution and Federalism Vision and Implementation. 2020. https://asiafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Nepals-Constitution-and-Federalism_Vision-and-Implementation_English.pdf. Accessed 10 Aug 2020.

Pradhan D. Nepal-data protection overview. 2020. https://www.dataguidance.com/notes/nepal-data-protection-overview. Accessed 14 July 2020.

Neupane A, Karki S. Nepal: an introduction to the Individual Privacy Act 2018. 2019. https://www.dataguidance.com/opinion/nepal-introduction-individual-privacy-act-2018. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

Neupane Law Associates. Introduction to the Privacy Act 2018. 2019. https://www.neupanelegal.com/news-detail/introduction-to-the-privacy-act-2018.html. Accessed 10 June 2019.

Upreti, R A. Individual Privacy Act, 2018. 2018. http://www.pioneerlaw.com/news/individual-privacy-act-2018-2075. Accessed 3 Jan 2019.

The World Bank. From transition to transformation: the role of the ICT Sector in Afghanistan. 2013. https://www.infodev.org/infodev-files/final_afghanistan_ict_role_web.pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2018.

Kraemer T. Afghanistan-data protection overview. 2020. https://www.dataguidance.com/notes/afghanistan-data-protection-overview. Accessed 23 Dec 2020.

Gunawardana K. Current status of information technology and its issues in Sri Lanka. 2018. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316383091_Current_Status_of_Information_Technology_And_Its_Issues_in_Sri_Lanka. Accessed 3 Mar 2018.

The morning. Data Protection Bill further delayed. 2020. http://www.themorning.lk/data-protection-bill-further-delayed/. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.