Abstract

In present study, a comparative efficiency analysis for silicon (Si), silicon carbide (SiC) metal oxide semiconductor field effect transistors (MOSFETs) and insulated gate bipolar transistor (IGBT) device based DC–DC boost converter is performed. Due to different gate-drive characteristics of power semiconductor devices such as Si, SiC MOSFETs and IGBT device, different voltage levels are required to drive aforementioned devices. A 500 W boost converter for wide input voltage range (30–72 V) and 110 V output voltage is designed having a single gate driver circuit for Si, SiC MOSFETs and IGBT. A single gate driver provides the gate-source (or base-emitter in case of IGBT) signal for all the devices which eliminates the use of separate gate driver circuit. Si MOSFET and IGBT are driven by 12 V gate-source voltage whereas SiC MOSFET is operated by 18 V gate-source voltage using the gate driver circuit. An experimental study is performed for the comparative efficiency analysis for Si, SiC MOSFETs and IGBT device based converter for 20 and 50 kHz switching frequencies. It is found that SiC based converter provides highest efficiency ≈ 97.8%, whereas the lowest efficiency ≈ 94% is found for IGBT based converter at 20 kHz switching frequency. SiC based converter gives higher efficiency because lower conduction loss owning to lower on-state resistance as compared to Si MOSFET. Besides this, SiC application has another advantage such as low switching loss at higher frequency resulting compact size of converter. However, use of IGBT at higher switching frequency results in higher switching losses, hence lower efficiency of the converter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

At present, applications of power semiconductor devices based system such as converters, inverters etc. in any electric system is ubiquitous. Highly efficient power semiconductor devices have shown a great application in converters and have led to higher efficiency, low weight and compact size of system in last few decades. The silicon (Si) metal oxide semiconductor field effect transistor (MOSFET) are widely used for voltage up to 600 V [1]. Nonetheless, Si power devices applications is limited concerning the high efficiency, high power density, high voltage and high temperature applications due to the inherent material characteristics. Aforementioned drawbacks makes Si device less competitive for the higher power and efficient applications. For higher voltage application such as 600 V and above, insulated gate bipolar transistors (IGBTs) have shown useful applications but they become less efficient at high frequency due to high switching losses (because it is a minority carrier device). In evolution of more advanced power electronics devices, silicon carbide (SiC) MOSFET is more advantages in high power and voltage applications due to higher switching speed, high operating electric field, low on-state resistance and higher breakdown voltages [2,3,4,5]. Wide energy band gap and high thermal conductivity of SiC device enable them to operate at higher temperature and power. SiC devices are more efficient because of lower switching and conduction losses as compared to the Si and IGBT [6, 7]. Table 1 provides the comparative analysis of electrical and thermal properties of Si and SiC devices [8,9,10,11].

Several studies have been carried out for efficiency comparison of Si and SiC MOSFETs based DC–DC converter. Masich et al. have performed the efficiency comparison between the Si and SiC MOSFETs based DC–DC boost converter. A high voltage gain boost converter was designed for low power application (≈ 20 W) which is suitable for light emitting diode (LED). DC–DC converter efficiency was improved from 76 to 89% and 68 to 81% with variation in the switching frequency from the 120 kHz to 20 kHz at 600 V and 900 V output voltage, respectively [12]. Han et al. have performed the comparative study on the efficiency, weight and volume of SiC and Si based bidirectional DC–DC converter for the hybrid electrical vehicle. They studied the three configurations such as IGBT device with silicon diode, IGBT with SiC Schottky diode and SiC MOSFET with SiC Schottky diode. A comparative efficiency analysis was carried out at 20 kHz switching frequency. The highest efficiency ≈ 99% was achieved with the use of SiC MOSFET with SiC Schottky diode at full load condition, whereas the efficiency for IGBT with SiC Schottky diode was 98.2%. The efficiency for the IGBT and silicon PN diode configuration was found to be 97.6%. There was significant reduction in weight of the converter from 8 to 3 kg with switching frequency of 20 kHz to 200 kHz, respectively. It was also observed that only the SiC based converter have efficiency higher than 90% at 200 kHz switching frequency [13]. Shi et al. have studied the SiC based on-board plug-in-electric vehicle (PEV) charger using single-ended primary-inductor converter (SEPIC) based power factor correction (PFC) converter followed by an isolated LLC resonant converter. It was found that the SEPIC-PFC converter achieved unity power factor, 2.72% total harmonic distortion, and 95.3% peak efficiency. The LLC converter achieved 97.1% peak efficiency. The overall efficiency of the PEV charger increased from 88.5 to 93.5% with increase in the load from 20% to full load [14]. Schrittwieser et al. [15] have done study on a three-phase buck PFC rectifier with integrated active filter for 380 V DC distribution systems that showed a peak efficiency ≈ 99% is achieved with SiC devices. Zhao et al. have performed comparative theoretical and experimental analysis for the isolated bidirectional DC–DC converter using Si and SiC devices. The SiC devices based converter showed the higher efficiency as compared to the Si based converter [16]. Rizzoli et al. have carried out a study on the performance evaluation of an inverter based on the soft and hard-switching SiC devices. It was found that hard-switching SiC inverter showed higher efficiency at lower output and also it was more economical as it eliminated the complex circuitry to drive the SiC MOSFET [17]. Anthon et al. have demonstrated the use of the SiC devices in multilevel grid-tied inverter. The use of the SiC devices reduced the semiconductor losses by more than 50% for similar rated capacity, load and frequency as compared to Si-IGBT device. In the application of the SiC device based inverter, the switching frequency was increased by 12 times while semiconductor losses were similar as in case of Si-IGBT inverter [18]. Ho et al. have done the performance comparison of interleaved boost converter based on the of Si and SiC diodes for photovoltaic applications. The use of SiC diode reduced the heat sink size (from 1031 to 388 cm3) and increased the converter efficiency by 0.6% [19]. In another study, Wang et al. have demonstrated the efficiency improvement in the 10 kW bidirectional electric vehicle charger using the variable DC bus voltage. It was found that efficiency increased by 0.7–1.25% using the variable DC bus voltage as compared to constant 600 V DC bus voltage [20]. Similar types of study for efficiency comparison of Si and SiC devices for DC–DC interleaved, bidirectional converter and inverter have been done [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. The thermal performance of the converter using Si and SiC MOSFETs has been studied in order to estimate the junction temperature, heat losses and temperature distribution [21, 30,31,32].

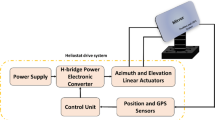

In present study, a comparative analysis of efficiency and losses for DC–DC converter is performed for different devices applications such as Si, SiC and IGBT. A 500 W power and 110 V output voltage DC–DC converter which have single gate driver circuit for all devices was developed in the laboratory. A theoretical prediction methodology is given which provides a details insight of conduction, switching losses for different devices along with inductor and capacitor losses. Three cases are studied to estimate the losses in the converter using theoretical prediction and experimental analysis such as (1) Si MOSFET + SiC diode, (2) SiC MOSFET + SiC diode, and (3) IGBT device + SiC diode.

Out of the three conventional DC/DC converter topologies i.e. buck, boost and buck-boost, boost topology is selected for the efficiency comparison. The reasons for choosing this topology are: (a) The input current of the boost converter is continuous which make it suitable to use with renewable power generators [33], (b) The gate driver circuit is not complex as it uses the low side driving circuitry. A single driver circuit is suitable to drive all types of power semiconductor devices namely Si, SiC MOSFET and IGBT, (c) With change in the duty cycle there is approximately no change in the efficiency whereas for other topologies the efficiency changes significantly. This characteristics is utilized for further enhancement in the efficiency [34].

2 Material and methodology

2.1 Gate driver circuit

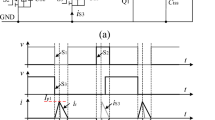

In this study for designing of boost converter, LM5022 controller is used as PWM generator whereas UCC27531 is used as the gate driver. Si MOSFET and IGBT require the 12 V (pk–pk) whereas SiC needs 18 V (pk–pk) as the driving voltage at the gate-source terminals. UCC27531 driver provides the necessary voltage to drive the Si, SiC and IGBT in the boost converter. UCC27531 utilizes the output PWM signal 7 V (pk–pk) of LM5022 controller and generate the required voltage signal (up to 18 V pk–pk) to drive all the devices used. A feedback regulator power supply circuit is designed which supply the power to the LM5022 boost controller and UCC27531 gate-driver. Feedback regulator circuit provides the stable voltage (12 V/18 V) irrespective of variation in the supply voltage (30–72 V). The schematic diagram of the feedback regulator circuit is shown in Fig. 1. In case of SiC MOSFET, higher gate-source voltage is required as compared to Si MOSFET because SiC carrier mobility and channel resistance are lower and higher, respectively in comparison with the Si. Higher the gate-source voltage lowers the drain-to-source resistance which gets saturated at a voltage of 18 V. If SiC is driven by the gate-source voltage of 12 V then drain–source on-resistance is lower. In this case, there will be higher losses in the device that will increase the temperature of the device. Increase in the temperature will further increase the on-resistance due to the decrease in the carrier mobility of SiC. Therefore, SiC device can be damaged due to the thermal runway [35]. The circuit layout of the studied boost converter is shown in Fig. 2. The regulated output voltage from the feedback regulator circuit is supplied to the pin 1 of LM5022 and pin 6 of UCC27531 to bias these ICs. The generated PWM (7 V pk–pk) from controller LM5022 from pin 5 is given to the pin 2 of UCC27531. This PWM signal of 7 V (pk–pk) is amplified to the desired voltage level in the range (12–18 V) at the same voltage that is generated by the feedback regulator circuit.

2.2 Converter losses theoretical calculation

There are several losses occur in DC–DC boost converter such as MOSFET switching and conduction losses, diode conduction losses, inductor and capacitor losses. All of these losses can be calculated theoretically. The methodology used in calculation of different losses are given as following.

2.2.1 MOSFET losses

The losses in the MOSFET can be calculated as follows:

2.2.1.1 Conduction loss

The conduction loss in the MOSFET is due to the drain–source on-resistance (RDS (on)). The on-resistance varies with change in the drain current and junction temperature. The voltage drop can be expressed as below:

Instantaneous value of the conduction loss can be formulated as follows:

The average value of the conduction loss for switching period can be expressed as below:

2.2.1.2 Switching loss

Switching loss of MOSFET majorly depends on the ON and OFF states energy losses of MOSFET. The MOSFET switching loss is calculated with considering the loss associated with ON and OFF states of the MOSFET. The ON-state energy loss is calculated without considering the loss associated with reverse recovery process of MOSFET. However, loss associated with the reverse recovery process with anti-parallel diode is considered for calculating the ON-state loss.

The switching loss of MOSFET is given by:

The values of parameters used in theoretical calculation of conduction and switching losses are taken from the MOSFET datasheets [36, 37].

2.2.2 IGBT losses

The IGBT conduction and switching losses are calculated in similar way as the conduction and switching losses are calculated for the MOSFET. The drain, source and gate for MOSFET are similar to the collector, emitter and base of IGBT, respectively. The conduction loss in IGBT is given by:

2.2.2.1 IGBT conduction loss

The instantaneous value of the conduction loss associated with IGBT is given by:

The average value of the IGBT conduction loss is represented as follows:

2.2.2.2 IGBT switching loss

IGBT switching loss is given by:

The values of parameters used in theoretical calculation of conduction and switching losses are taken from the IGBT datasheet [38].

2.2.3 Diode losses

The boost converter diode also has two types of losses such as conduction and switching losses. These losses can be explained as below:

2.2.3.1 Diode conduction loss

Conduction loss in diode can be formulated as below:

2.2.3.2 Diode switching loss

Switching loss in diode can be expressed as below:

The values of parameters used in theoretical calculation of conduction and switching losses are taken from the Schottky diode datasheet [39].

2.2.4 Inductor and capacitor losses

In the inductor, there are major losses such as conduction or copper losses. These losses can be expressed as below:

and ∆I is the ripple current which is approximately 30% of the output current and \(\Delta I^{2}\) can be neglected. Therefore, the inductor conduction loss can be simplified as below:

In the capacitor the losses can be expressed as:

2.3 Experimental setup

An experimental study is performed with the DC–DC boost converter (110 V, 500 W) for the comparative efficiency analysis using Si, SiC MOSFET and IGBT. The details of the power semiconductor devices such as Si, SiC MOSFETs, IGBT and diodes are given in Table 2. The designed prototype of the boost converter is shown in Fig. 3 and the power semiconductor devices (Si and SiC MOSEFT, IGBT and SiC diode) used in the study is shown in Fig. 4.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Theoretical prediction of losses in DC–DC converter

The theoretical prediction of different losses in DC–DC converter is shown in Figs. 5, 6, 7 and 8 for different switching frquencies and power. These losses are calculated uisng the Eqs. (1)–(13).

Figures 5 and 6 show the comparison between different losses for 250 W and 500 W power output, respectively at 20 kHz switching frequency. It was found that at 20 kHz frequency and 250 W power output, IGBT incurs maximum conduction loss ≈10 W followed by the Si (7 W) and SiC (3 W). In comparison of switching loss for 250 W power output, IGBT has maximum ≈ 9 W followed by Si ≈ 3 W and SiC ≈ 2 W. Diode loss (1.5 W) is similar for all IGBT, Si and SiC applications in the converter. Inductor losses are found to be ≈ 2 W at 20 kHz switching frequency. The similar pattern for losses is followed for the 500 W load power at 20 kHz switching frequency.

However, at 50 kHz switching frequency, total losses increases for all the devices. As shown in Fig. 7 at 50 kHz switching frequency and 250 W load, power conduction and switching losses increase for all devices as compared to 20 kHz frequency, however it is still higher for the IGBT followed by the Si and SiC. Similar pattern is followed for 500 W power at 50 kHz frequency as shown in Fig. 8. Inductor loss also increases as the switching frequency increases. However, inductor and capacitor losses increase as load power increases from 250 to 500 W at 50 kHz frequency.

Conduction loss majorly depends on the load current, junction temperature, duty cycle while switching loss is function of switching speed, load voltage, load current and junction temperature. The conduction loss in the SiC is less than its counterparts because the on-state resistance is low. The resistance of SiC device is dependent on the applied voltage, its off-state resistance is high. SiC on-state resistance decreases significantly until a threshold voltage is applied to it and maintains this resistance until applied voltage is below threshold voltage. The on-state resistance is majorly depends on the thickness of drift layer. In SiC, the thickness of drift layer is reduced 10 times as compared to Si while the concentration of doping is kept in magnitude of same order in case of Si. Therefore, the SiC offers almost 10 times lesser on-state resistance as compared to Si. In contrast of SiC, Si MOSFET on-state resistance increases with increase in the gate-source voltage. The increment in the on-state resistance of Si MOSFET is proportional to square of voltage to gate to source voltage. The switching losses in IGBT are higher than the SiC MOSFET, because due to inherent bipolar characteristic of IGBT. Being as bipolar device the conduction in the IGBT happens due to both electrons and holes. Therefore, during the transition from on-state to off-state, there are some electrons and holes are trapped in the channel. Therefore, IGBT will not be fully turned off until all electrons and holes are recombined. During this transition time, miller capacitance holds some gate voltage, therefore some losses happens during this period. SiC device has unipolar conduction which happens due to electrons flow only. During the transition from the on state to off state, only electrons flow is inhibited by closing the channel. Therefore, there is no delay in the turning off completely in the SiC MOSFET.

3.2 Experimental efficiency analysis of the converter

This section explains the experimental analysis of efficiency in the DC–DC converter.

The efficiency comparison of Si, SiC MOSFETs and IGBT device based DC–DC boost converter for three different input voltages 30 V, 50 V and 72 V is shown in Figs. 9a, b, 10a, b, and 11a, b, respectively. In Fig. 9a, efficiency comparison is shown for 20 kHz switching frequency at 30 V input voltage. The converter efficiency increases with increase in the output power. The efficiency is highest for SiC MOSFET based converter and was found to be 95.8%. The efficiency for Si MOSFET and IGBT are found to be 94.6% and 92.6%, respectively. In Fig. 9b, the converter efficiency comparison is done for 50 kHz switching frequency at the 30 V input voltage. The highest efficiency is 93.4% for SiC based converter, whereas the efficiency is lower for Si MOSFET and IGBT which are found to be 91.8% and 88.4%, respectively. In Fig. 10a, b, the efficiency comparison is done for 50 V input voltage at 20 kHz and 50 kHz switching frequency. It is shown in Fig. 10a that the efficiency is higher for SiC MOSFET and it is found to be 96.7%, whereas the lowest efficiency is for IGBT and it is found to be 93.8%. From Fig. 10b, it is clear that efficiency decreases with increase in the frequency for all the devices. The efficiency for SiC MOSFET decreases to 94.7% from 96.7%, whereas the efficiency for IGBT decreases to 89.6% from 93.8%. In Fig. 11a, b the efficiency comparison is done for 72 V input voltage at two different switching frequencies of 20 kHz and 50 kHz. From Fig. 11, it is clear that the efficiency is still highest 97.8% in case of SiC, whereas the lowest efficiency is found for IGBT which is 93.9%.The efficiency for SiC decreases to 95.8% (at 50 kHz) from 97.85% (at 20 kHz) and for IGBT the efficiency decreases to 89.7% (at 50 kHz from 93.4% (at 20 kHz). The application of SiC converter improves the efficiency of converter significantly due to lower conduction losses (lower on-resistance and low parasitic capacitance) as compared to Si and IGBT. Besides this, SiC has faster ON and OFF transitions, therefore it has lower switching losses.

The converter efficiency increases with increase in the load power (as power output increases while switching loss does not vary much). Nonetheless, efficiency further decreases with increase in the output power (further increase in the load power, conduction loss dominates more). Therefore, efficiency comes lower for further increase in the load power.

3.3 Comparison between experimental and theoretical predicted efficiencies

At 50% of the total load, the calculated and measuered efficiency differences at 20 kHz and 50 kHz are given in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Calculated and measuered efficency differences for full load condition at 20 kHz and 50 kHz are given in Tables 5 and 6 respectively.

The theoretical prediction is also given for the conduction and switching losses in power transistor devices and inductor and capacitor losses. Tables 3 and 4 give the difference in the measured and theoretical efficiencies for 250 W power at 20 kHz and 50 kHz switching frequency, respectively. Tables 5 and 6 provide the difference in theoretical and measured values of efficiency for 500 W at 20 kHz and 50 kHz switching frequency, respectively. There is slight difference between the theoretical and experimentally measured values. There is reason which can causes the difference between the theoretical and measured values such as (1) Leakage losses in the parasitic resistance, capacitance and inductor in the converter circuit layout which are not considered in the theoretical prediction, (2) Parameter values for different devices Si, SiC and IGBT in theoretical prediction are taken from the respective datasheet provided by the manufacturer which were obtained at the standard test condition and may be different in actual working condition, (3) Variable nature of switching frequency which is sensitive to unincorporated parasitic elements in the theoretical prediction.

4 Conclusions

In this study, the comparison in the efficiency of the DC–DC boost converter using the Si and SiC MOSFETs and IGBT device has been studied on the basis of theoretical predictions and experimental analysis. Three cases such as (1) Si MOSFET + SiC diode, (2) SiC MOSFET + SiC diode, and (3) Si IGBT + SiC diode are compared to evaluate the comparative efficiency and losses for given power output at different operating frequency such as 20 kHz and 50 kHz. It was found that at lower frequency (20 kHz), the efficiency of DC–DC converter is maximum 97.8% and followed by Si and IGBT. However, the converter efficiency drops for all three aforementioned cases with increase in the switching frequency. The SiC MOSFET + SiC diode based converter gives maximum efficiency because of low conduction and switching losses. Conduction loss in SiC is lowest due to lower on-state resistance as compared to Si MOSFET and IGBT. Switching loss is also lowest in case of SiC MOSFET + SiC diode application due to the low miller capacitance (parasitic capacitance). The details comparative analysis of conduction, switching loss, inductor loss and capacitor loss are also given for Si, SiC and IGBT devices in the converter. Conduction loss is maximum for IGBT followed by the Si and SiC. It is concluded that the application of the combination of power semiconductor devices (SiC MOSFET + SiC Schottky diode) in DC–DC converter provides the highest efficiency as compared to Si and IGBT devices.

Abbreviations

- \(E_{on,IGBT}\) :

-

IGBT on state energy loss (J)

- \(E_{off,IGBT}\) :

-

IGBT off state energy loss (J)

- \(E_{on,M}\) :

-

MOSFET on state energy loss (J)

- \(E_{off,M}\) :

-

MOSFET off state energy loss (J)

- \(ESR\) :

-

Effective series resistance (Ω)

- \(f_{sw}\) :

-

Switching frequency (kHz)

- \(i_{C}\) :

-

Collector current (A)

- \(I_{Cav}\) :

-

Average collector current (A)

- \(I_{Crms}\) :

-

Collector rms current (A)

- \(i_{D}\) :

-

Drain current (A)

- \(I_{Drms}\) :

-

Drain rms current (A)

- \(I_{Lrms}\) :

-

Inductor rms current (A)

- \(I_{o}\) :

-

Output current (A)

- \(P_{con,D}\) :

-

Diode conduction loss (W)

- \(P_{con,M}\) :

-

MOSFET conduction loss (W)

- \(P_{con,IGBT}\) :

-

IGBT conduction loss (W)

- \(P_{sw,IGBT}\) :

-

IGBT switching loss (W)

- \(P_{sw,M}\) :

-

MOSFET switching loss (W)

- \(Q_{c}\) :

-

Schottky diode junction charge (C)

- \(R_{C}\) :

-

Collector resistance (Ω)

- \(R_{dc}\) :

-

Inductor DC resistance (Ω)

- \(R_{DS(on)}\) :

-

Drain to source on resistance (Ω)

- \(T_{sw}\) :

-

Switching period (s)

- \(v_{CE}\) :

-

Instantaneous collector to emitter voltage (V)

- \(v_{CEO}\) :

-

Collector to emitter voltage (V)

- \(v_{DS}\) :

-

Instantaneous drain to source voltage (V)

- \(V_{DS}\) :

-

Drain to source voltage in off condition (V)

- \(V_{fD}\) :

-

Diode on state voltage drop (V)

- \(V_{o}\) :

-

Output DC voltage (V)

References

Carr JA, Hotz D, Balda JC, Mantooth HA, Ong A, Agarwal A (2009) Assessing the impact of SiC MOSFETs on converter interfaces for distributed energy resources. IEEE Trans Power Electron 24:260–270

Cooper JA, Agarwal A (2002) SiC power-switching devices—the second electronics revolution. Proc IEEE 90:956–968

Singh R, Cooper JA, Melloch MR, Chow TP, Palmour JW (2002) SiC power Schottky and PiN diodes. IEEE Trans Electron Devices 49:665–672

Rabkowski J, Peftitsis D, Nee HP (2012) Silicon carbide power transistors—a new era in power electronics is initiated. IEEE Ind Electron Mag 6:17–26

Millan J, Godignon P, Perpina X, Pereztomas A, Rebollo J (2014) A survey of wide bandgap power semiconductor devices. IEEE Trans Power Electron 29:2155–2163

Zhao T, Wang J, Huang AQ, Agarwal A (2007) Comparisons of SiC MOSFET and Si IGBT based motor drive systems. In: Proceedings on IEEE industry applications conference, pp 331–335

Biela J, Schweizer M, Wafer S, Kolar JW (2011) SiC versus Si evaluation of potentials for performance improvement of inverter and DC–DC converter systems by SiC power semiconductors. IEEE Trans Ind Electron 58:2872–2882

Bhatnagar M, Baliga BJ (1993) Comparison of 6H-SiC, 3C-SiC, and Si for power devices. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 40:645–655

Elasser A, Chow TP (2002) Silicon carbide benefits and advantages for power electronics circuits and systems. Proc IEEE 90:969–986

Hudgins JL, Simin GS, Santi E, Khan MA (2003) An assessment of wide bandgap semiconductors for power devices. IEEE Trans Power Electron 18:907–914

Rujas A, López VM, Bediaga AG, Berasategi A, Nieva T (2017) Influence of SiC technology in a railway traction DC–DC converter design evolution. In: IEEE Energy conversion congress and exposition (ECCE), Cincinnati, OH, pp 931–938

Masich AL, Blavi HV, Moncusí JMB, Salamero LM (2015) Efficiency comparison between Si and SiC-based implementations in a high gain DC–DC boost converter. IET Power Electron 8:869–878

Han D, Noppakunkajorn J, Sarlioglu B (2014) Comprehensive efficiency, weight, and volume comparison of SiC- and Si-based bidirectional DC–DC converters for hybrid electric vehicles. IEEE Trans Veh Technol 63:3001–3010

Shi C, Wang H, Dusmez S, Khaligh A (2017) A SiC-based high-efficiency isolated onboard PEV charger with ultrawide DC-link voltage range. IEEE Trans Ind Appl 53:501–511

Schrittwieser L, Kolar JW, Soeiro TB (2017) 99% efficient three-phase buck-type SiC MOSFET PFC rectifier minimizing life cycle cost in DC data centers. CPSS Trans Power Electron Appl 2:47–58

Zhao B, Song Q, Liu W (2014) Experimental comparison of isolated bidirectional DC–DC converters based on all-Si and all-SiC power devices for next-generation power conversion application. IEEE Trans Ind Electron 61:1389–1393

Rizzoli G, Mengoni M, Zarri L, Tani A, Serra G, Casadei D (2019) Comparative experimental evaluation of zero-voltage-switching Si inverters and hard-switching Si and SiC inverters. IEEE J Emerg Sel Top Power Electron 7:515–527

Anthon A, Zhang Z, Andersen MAE, Holmes DG, McGrath B, Teixeira CA (2017) The benefits of SiC mosfets in a T-Type inverter for grid-tie applications. IEEE Trans Power Electron 32:2808–2821

Ho CNM, Breuninger H, Pettersson S, Escobar G, Canales F (2013) A comparative performance study of an interleaved boost converter using commercial Si and SiC diodes for PV applications. IEEE Trans Power Electron 28:289–299

Wang X, Jiang C, Lei B, Teng H, Bai HK, Kirtley JL (2016) Power-loss analysis and efficiency maximization of a silicon-carbide MOSFET-based three-Phase 10-kW bidirectional EV charger using variable-DC-bus control. IEEE J Emerg Sel Top Power Electron 4:880–892

Cougo B, Schneider H, Meynard T (2015) High current ripple for power density and efficiency improvement in wide bandgap transistor-based buck converters. IEEE Trans Power Electron 30:4489–4504

Zdanowski M, Kostov K, Rabkowski J, Barlik R, Nee HP (2014) Design and evaluation of reduced self-capacitance inductor in DC/DC converters with fast-switching SiC transistors. IEEE Trans Power Electron 29:2492–2499

Biela J, Schweizer M, Waffler S, Kolar JW (2011) SiC versus Si—evaluation of potentials for performance improvement of inverter and DC–DC converter systems by SiC power semiconductors. IEEE Trans Ind Electron 58:2872–2882

Hazra S, Madhusoodhanan S, Moghaddam GK, Hatua K, Bhattacharya S (2016) Design considerations and performance evaluation of 1200-V 100-A SiC MOSFET-based two-level voltage source converter. IEEE Trans Ind Appl 52:4257–4268

Xu F, Guo B, Tolbert LM, Wang F, Blalock BJ (2013) An all-SiC three-phase buck rectifier for high-efficiency data center power supplies. IEEE Trans Ind Appl 49:2662–2673

Kasper M, Bortis D, Kolar JW (2014) Classification and comparative evaluation of PV panel-integrated DC–DC converter concepts. IEEE Trans Power Electron 29:2511–2526

Alfotouh AMA, Radun AV, Chang HR, Winterhalter C (2006) A 1-MHz hard-switched silicon carbide DC–DC converter. IEEE Trans Power Electron 21:880–889

Vechalapu K, Bhattacharya S, Brunt EV, Ryu SH, Grider D, Palmour JW (2017) Comparative evaluation of 15-kV SiC MOSFET and 15-kV SiC IGBT for medium-voltage converter under the same dv/dt conditions. IEEE J Emerg Sel Top Power Electron 5:469–489

Wang YF, Xue LK, Wang CS, Wang P, Li W (2016) Interleaved high-conversion-ratio bidirectional DC–DC converter for distributed energy-storage systems—circuit generation, analysis, and design. IEEE Trans Power Electron 31:5547–5561

Hazra S, De A, Cheng L, Palmour J, Schupbach M, Hull BA, Allen S, Bhattacharya S (2016) High switching performance of 1700-V, 50-A SiC power MOSFET over Si IGBT/BiMOSFET for advanced power conversion applications. IEEE Trans Power Electron 31:4742–4754

Kim T, Jang M, Agelidis VG (2015) Practical implementation of a silicon carbide-based 300 kHz, 1.2 kW hard-switching boost-converter and comparative thermal performance evaluation. IET Power Electron 8:333–341

Jiang D, Burgos R, Wang F, Boroyevich D (2012) Temperature-dependent characteristics of SiC devices: performance evaluation and loss calculation. IEEE Trans Power Electron 27:1013–1024

Graditi G, Colonnese D, Femia N (2010) Efficiency and reliability comparison of DC–DC converters for single phase grid connected photovoltaic inverters. In: SPEEDAM Pisa, pp 140–147

Glasner I, Appelbaum J (1996) Advantage of boost vs. buck topology for maximum power point tracker in photovoltaic systems. In: Proceedings of 19th convention of electrical and electronics engineers Jerusalem, Israel, pp 355–358

Zhou W, Zhong X, Sheng K (2014) High temperature stability and the performance degradation of SiC MOSFETs. IEEE Trans Power Electron 29:2329–2337

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alam, M., Kumar, K. & Dutta, V. Comparative efficiency analysis for silicon, silicon carbide MOSFETs and IGBT device for DC–DC boost converter. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1700 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1778-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1778-4