Abstract

The rheological parameters, yield stress, flow index, consistency, and plastic viscosity of cement grouts are important parameters for the quality control of these materials. These parameters are assessed from the rheogram using a rheological model. Cement slurries without additive indicated a non-Newtonian type of rheological behaviour with yield stress. On the other hand, the mixtures containing a viscosifying agent exhibit a shear-thinning rheological behaviour which is much more important than the mixtures without a viscosifying agent. In this work, we formulated non-hydrated Algerian bentonite cement slurry in the presence of a superplasticizer. Cement was replaced cement by bentonite in five different substitution rates (2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, and 10%) and the water/binder ratio was fixed at 0.5. For this, various rheological tests were realized by using a controlled stress rheometer. In order to show the influence of bentonite on the rheological behaviour of the different grouts, several flow tests were carried out for a range of shear rates between 0.01 and 200 s−1. To properly adjust the different rheograms, various rheological models were used such as the models of Bingham, Herschel–Bulkley, modified Bingham, Casson, De Kee, Vom Berg, Yahia and Papanastasiou. For the correct choice of the rheological model, it was based on the calculation of the standard error. It was found that the rheological models of Herschel–Bulkley and Papanastasiou made it possible to better describe the flow curves compared to the other rheological models. It has been found that as the content of bentonite increases, the yield stress and the consistency evolve drastically, by cons the flow index decreases progressively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Grouting technique has been widely applied in various application such as civil, mining [1,2,3,4], geothermal, and petroleum engineering.

Grouting is a method efficient which applied to fill the pore spaces, faults, cracks and voids of rock and soil and defects in structural concrete and masonry. It also permits to improve the physical and mechanical properties of these materials in geotechnical projects. There are many technics of grouting, and one of the most common methods is permeation grouting. Cement-based or chemical grouts are used for permeation grouting.

Cement Grouts are considered as complex materials, their rheological behaviours affected by many factors, namely water-to-binder ratio, cement properties, dosage and type of chemical admixtures, supplementary cementitious materials (silica fume, metakaolin, calcined shale, bentonite), temperature, pressure, and time [5,6,7], it has wide application in engineering in reason of their good mechanical durability, of its low cost, and environmentally friendly.

One of the main goals of sustainable development is to use rationally of natural resources. For this,the cement grout can be obtained by mixing of necessary quantities of cement, bentonite, and water.

The elaboration and performance of cement grout were extensively investigated by several researchers in recent years. The water-retention, rheological behaviour, bleeding, and mechanical strength of cement grout bring significant changes by the addition of an amount of admixtures and supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) [6, 8, 9].

The assess of rheological parameters of cement grouts is of great importance. So, these properties affect the pumpability of grouts to fill voids and cracks. The optimization of rheological parameters such as viscosity, flow index, and yield stress of cement-grout is primordial to predict the ease of placements. The yield stress represents the limit between two elastic and viscous behaviours. The fluid begins to flow when the imposed stress exceeds the yield stress. Therefore, the location of grout into voids or fissures will essentially depend on its yield stress.

The viscosity is an important property of fluids that describes a resistance of fluids to the flow and that is related to the mutual interactions of the elements of which it is composed. The viscosity is an important property of fluids that describes a resistance of liquids to the flow under shear stress, and that is related to the mutual interactions of the elements of which it is composed. It is the most important factor relative to grout blend formulation. The injection of cement grout into narrow cracks requires the use of low viscosity grout to increase the penetration distance in the cracks. To limit the penetration of the grout or to fill large fractures or often uses very viscous grouts. Viscosity is also an important factor in avoiding segregation, which is caused between the constituents of the mixture that can be caused by precipitation. Therefore, it is crucial to have a stable and homogeneous grout.

There are only very few experimental studies published in the literature on the influence of bentonite on the rheological properties of cement grout [10,11,12,13]. Benyounes et al. investigated the effect of bentonite on the rheological behavior of cement grout, in their studies, they have only used the Herschel–Bulkley model for estimating the rheological parameters of cement grouts. They reported that the bentonite leads to the increase in apparent viscosity, yield stress, and consistency of cement grout

The aim of this study is to apply certain rheological models that can be used to describe rheological behavior of cement grouts in presence of Algerian bentonite and assess the different rheological parameters for each model.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

In this work, bentonite clay used as partial replacement of cement was obtained from a deposit in the Maghnia region, in Tlemcen province. It is marketed by the Bental company. Maghnia bentonite is rich in montmorillonite,

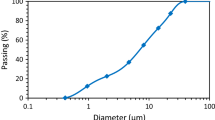

The chemical composition of bentonite carried out by X-ray fluorescence spectrometer is reported in Table 1. The mineralogical composition of bentonite was determined using XRD, the results are shown in Fig. 1. CEM I conforming to ASTM C 150 [14] was used, it is composed of 95% of clinker and 5% of gypsum, the chemical and mineralogical compositions are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

2.2 Sample preparation and experimental protocol

The blended cements were prepared by mixing 100 g of powder (cement and bentonite) with an appropriate quantity of water containing predissolved superplasticizer. The time of mixing is 2 min, in order to ensure a good homogeneity of samples. The ratio water/binder was fixed at 0.5 by masse. Rheological measurements were carried out using a coaxial rotating cylinder through a controlled stress rheometer (AR2000 from TA Instruments) equipped with vane geometry. The temperature was maintained at 20 °C by the circulation of water through a jacket encircling the outer cylinder. The samples are presheared at 100 s−1 during 2 min before the beginning of the each rheological test. During the rheological test, The shear rate parameter has a great influence on the rheological properties of cement grouts. For each sample, the rheological measurements were performed by progressively varying the shear rate from 0.01 to 200 s−1 for 10 min. In this experimental work, the down-curve was selected for the better fit of rheological behaviour of the cement grouts.

3 An overview of some rheological model

The imposed force to a fluid determines the shear rate, which in jet grouting terms is determined by the flow rate of the fluid through a particular geometrical configuration.

The resistance of the fluid to the applied force is called the shear stress, which is similar to the pump pressure.

The relationship between shear stress and shear rate and its impact on cement slurry characteristics is an important factor to characterize the rheology of cement grout, rheological parameters such as yield stress, plastic viscosity, flow index(shear thinning or shear thickening behaviour) are need to be described. It is almost difficult to grasp, with sufficient precision, all the rheograms by the use of a single rheological model. Considerable efforts have been made by several researchers to model the rheology of blended cement pastes.

In the literature, there are many numbers of empirical models that are proposed, some are extensively used and accepted, while the use of some is very limited. Thus, eight models will be reviewed here, and a choice will be made among them.

3.1 Bingham model

The Bingham model (Bingham, 1922) is given as follows:

The materials obeying to this model are characterized by a yield stress (\(\tau_{0}\)) and a plastic viscosity (\(\mu_{p}\)) which is independent of the shear rate (\(\dot{\gamma })\).

Given it only contains only two rheological parameters, It is quite easy to integrate it into analytical solutions. This model has been the most commonly used to describe rheological behaviour of cementitious materials [15,16,17,18].

3.2 Modified Bingham model

The other most adequate model describing the rheological behaviour of fluids is the modified Bingham model which is given by the equation

This modified model represents a development of the Bingham model containing a second order term. Where c is a constant, its value is very low [5].

3.3 Herschel–Bulkley model

It proves necessary to add others parameters in the Newtonian and non Newtonian regions to well describe the flow of fluids. Herschel–Bulkley is a three-parameter model which permits to improve the Bingham model by the addition of Power law expression in replacement of the plastic viscosity [19, 20]. The Herschel–Bulkley model is given by the following equation:

where k is the consistency, and n is the flow index. Herschel–Bulkley behaviour is the same as the Bingham behaviour when n is equal to 1. This model has been used to describe the rheological behaviour of cementitious materials such as fresh concrete [21], mortar pastes [22], cement paste [23], and cement grouts [9, 11]

3.4 Casson model

Casson [24] is rheological model that include two adjustable parameters and is given by the following equation:

where \(\eta_{\infty }\) represents the infinite viscosity.

The representation of the nonlinearity of yield-pseudoplastic behaviour of blended cements by the use of Casson law has been reported in past works [15, 25,26,27,28,29,30]

3.5 De Kee–Turcotte model

De Kee is an another rheological model that include three parameters, which takes into account a time-dependent parameter. The equation is:

where \(\alpha\) is a time-dependent parameter.

This model was used for the first time to describe the rheological behaviour of biomaterials. The model proposed by De Kee permits to replace the Casson law. De Kee model has been applied for the cement-based mixtures by different research workers [15, 31]

3.6 Vom Berg model

Vom Berg has proposed a rheological model for describing the flow behavior of cement pastes for elevated shear rates [32]. The mathematical formula of Vom Berg model is given as follows:

where b, and c are constants

This model contains three adjustable parameters that integrate a yield stress and two constants (b, c).

3.7 Yahia–Khayat model

The rheological model proposed by these authors is the combination of Casson and De Kee models

This model has given a better prediction of rheological profiles of high-performance grout made with W/CM ratio of 0.40, containing supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), such as silica fume, and blast furnace in presence of welan gum.

3.8 Papanastasiou model

The Bingham plastic model is chiefly applied in simple unidirectional problems, but for complex fluids, this ideal model is difficult to use in theoretical and numerical analyses because it is discontinuous and singular at vanishing shear rates. One useful model used to surmount this difficulty is the modified Bingham model proposed by Papanastasiou [33], who integrated a regularization parameter(a) that controls the exponential increase of stress of stress at low shear rates. Mitsoulis and Abdali [34] have regularised the Herschel–Bulkley model to predict shear thinning behaviour in the low and high stress state (yielded – unyielded region) by using the Papanastasiou approach. The Herschel–Bulkley–Papanastasiou (HBP) is written as follows:

HBP model can be reduced to a Bingham model by fixing the exponential growth of stress to 0 and the flow index n to 1. In most commercial fluid-flow simulation software packages, the Papanastasiou rheological model is integrated

4 Statistical treatments

For each sample of cement grouts tested in this work, the data of shear stress related to various shear rates were adjusted by employing the rheological models presented earlier. So as to evaluate the goodness of and accuracy of fit between the experimental shear stress-shear rate data and the rheological models for each cementitiuous material. The estimation of statistical parameters in terms of error is calculated between the measured shear stress during the experiment and the predicted shear stress from rheological model. To assess the accuracy of rheological models, the statistical parameter standard error (SE) is calculated, which is expressed as follows:

where Xm is the measured value and Xc is the calculated value of x for each data point, n is the number of data points.

5 Results and discussion

5.1 Shear stress-shear rate curve

The changes in flow curves of cement grout at various bentonite content are shown in Fig. 2. It can be clearly seen that the apparent viscosity of the grouts increases with increasing of bentonite content. Beyond the concentration of 4% in bentonite, the non-Newtonian behaviour of cement grout becomes more visible.

The existence of the yield stress is confirmed by the increasing of bentonite concentration. This can be attributed to the presence of an open three-dimensional network created by the contact between clay and cement particles. The analysis of the rheograms makes it possible to affirm that the grouts are in the quasi-solid state for low shear rates.

For flow curves that correspond to contents ≥ 6% in bentonite, it is observed that the appearance of a stress plateau that marks the transition from an elastic solid state to a viscous liquid state. The flow of grouts will occur when the intensity of the applied stress exceeds the value of the yield stress. This yield stress is directly related to the attraction energy between the particles which controls the cohesion of the cement-bentonite system.

As illustrated in Table 4, for cement mixtures with high bentonite content, the wrong fitting of the rheograms was obtained with the more viscous grouts corresponding to high values of standard error, regardless of the rheological model used. The Bingham and Yahia–Khayat models resulted in the unfavorable fitting, especially for mixtures with high bentonite content (> 6%). The value of error standard was of 77.65 for Bingham and Yahia–Khayat models, the values of standard error for modified Bingham, Casson, De Kee, Vom Berg, Papanastasiou, and Herschel models were 49.13, 44.92, 42.06, 21.02, 18.15, and 18.15, respectively. In general, the Herschel–Bulkley and Papanastasiou models allowed better fitting of the experimental flow curves regardless the bentonite content.

5.2 Effect of bentonite on rheological parameters

Figure 3 presents the yield values of grout mixes made with various percentages of bentonite estimated by different rheological models. Increasing the percentage of bentonite resulted in an increase in yield stress value.

In this work, the infinite viscosity is only quantified by the Casson and Yahia models. Whatever the bentonite content, the infinite viscosity following the Yahia model is high in comparison to Casson model. It is clear that the rise of bentonite content leads to the increase of infinite viscosity for the Yahia rheological model (Fig. 4), the infinite viscosity ranges between 0.068 and 0.405 Pa s. Concerning the Casson model, the infinite viscosity is quasi-stable for bentonite content ≤ 8%, wich varies between 0.05 and 0.065 Pa s, by cons for the mixture with 10% bentonite, the infinite viscosity was of 0.112 Pa s.

The consistency of mixtures can be assessed using the Herschel–Bulkley and Papanastasiou models (Fig. 5). From the Herschel–Bulkley model analysis, the obtained consistency ranges between 0.035 and 28 Pa sn, the consistency varies between 0.03 and 12.60 Pa sn following the Papanastasiou model analysis.

Regardless of the used models, the consistency was relatively constant between 2% and 4% in bentonite content (0.031–0.038 Pa sn). Beyond the 6% bentonite content, the consistency rises drastically (0.15–28.00 Pa sn), indicating a high degree of interaction between bentonite and cement particles for high bentonite content.

Figure 6 shows the variation of flow index of cement grouts as a function of bentonite content. The values of the flow index vary from 0.295 to 1.127 for the Herschel–Bulkley model, concerning the Papanastasiou model the values of flow index are situated between 1.157 and 0.408. The values of flow index for Papanastasiou model are higher compared to Herschel–Bulkley model. Based on the results obtained, it can be affirmed that the shear thickening response is most likely to be predominant with slightly concentrated bentonite content. The mixture becomes shear-thinning when the bentonite content increases.

6 Conclusion

The impact of bentonite on the rheological parameters, i.e., yield stress (τ0), fluid consistency (k), infinite viscosity (∞), and fluid index (n) of cement grout is presented in this work. This study was conducted by fitting experimental data of the shear stress-shear rate using eight rheological models. It was found that the rheological models of Herschel–Bulkley and Papanastasiou made it possible to better describe the rheograms compared to the other rheological models, which exhibit the lower values of standard error. It has been shown that as the content of clay rises, the yield stress and the consistency evolve drastically, by cons the flow index decreases progressively. The highest value of yield stress was observed for the Bingham and Yahia–Khayat models followed by the modified Bingham, De Kee, Casson, Vom Berg modes, respectively. Based on the minimum values of error standard, the Papanastasiou model shows the lowest values. Therefore, The Papanastasiou model enables better fitting of the flow curves.

References

Zhang Q, Li J, Liu B, Chen X (2011) Directional drainage grouting technology of coal mine water damage treatment. Proc Eng 26(Supplement C):264–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2011.11.2167

Elwakil AZ, Azzam WR (2016) Soil improvement using grout walls. Alex Eng J 5:4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2016.05.017

Domone PL (1990) The properties of low strength silicate/portland cement grouts. Cement Concrete Res 20(1):25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/0008-8846(90)90113-C

Indacoechea-Vega I, Pascual-Muñoz P, Castro-Fresno D, Calzada-Pérez MA (2015) Experimental characterization and performance evaluation of geothermal grouting materials subjected to heating–cooling cycles. Constr Build Mater 98:583–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.08.132

Sonebi M (2006) Rheological properties of grouts with viscosity modifying agents as diutan gum and welan gum incorporating pulverised fly ash. Cement Concrete Res 36(9):1609–1618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2006.05.016

Sonebi M (2010) Optimization of cement grouts containing silica fume and viscosity modifying admixture. J Mater Civ Eng 22(4):332–342. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0000026

Nehdi M, Martini SA (2007) Effect of temperature on oscillatory shear behavior of portland cement paste incorporating chemical admixtures. J Mater Civ Eng 19(12):1090–1100. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0899-1561(2007)19:12(1090)

Tan O, Zaimoglu AS, Hinislioglu S, Altun S (2005) Taguchi approach for optimization of the bleeding on cement-based grouts. Tunn Undergr Space Technol 20(2):167–173

Sonebi M, Bassuoni MT, Kwasny J, Amanuddin AK (2015) Effect of nanosilica on rheology, fresh properties, and strength of cement-based grouts. J Mater Civ Eng 27(4):04014145. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0001080

Al-Kholidi AH, Youhong S, Zhifeng S (2013) Rheological behaviour and compressive strength of cement bentonite grout slurry. In: Wang F, Miyajima M, Li T, Shan W, Fathani TF (eds) Progress of geo-disaster mitigation technology in Asia. Environmental science and engineering. Springer, Berlin, pp 611–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-29107-4_38

Benyounes K, Benmounah A (2014) Effect of bentonite on the rheological behavior of cement grout in presence of superplasticizer. Int J Civ Archit Struct Constr Eng 8(11):1095–1098

Gunter A (1978) The properties and behaviour of bentonite/cement slurries. King’s College London (University of London), London

Mesboua N, Benyounes K, Benmounah A (2018) Study of the impact of bentonite on the physico-mechanical and flow properties of cement grout. Cogent Eng 5(1):1446252. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311916.2018.1446252

ASTM (2012) Standard specification for portland cement. ASTM C 150/C150M-15; ASTM international: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015

Yahia A, Khayat KH (2003) Applicability of rheological models to high-performance grouts containing supplementary cementitious materials and viscosity enhancing admixture. Mater Struct 36(6):402–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02481066

Medina C, Banfill P, Sánchez de Rojas M, Frías M (2013) Rheological and calorimetric behaviour of cements blended with containing ceramic sanitary ware and construction/demolition waste. Constr Build Mater 40:822–831

Li B, Mao J, Lei H, Liu Z, Toyoharu N (2016) Investigation of the rheological properties of cement paste with different superplasticisers based on colour function and RDS methods. Adv Cement Res 28(6):357–370. https://doi.org/10.1680/jadcr.15.00133

Yim HJ, Kim JH, Kwon SH (2016) Effect of admixtures on the yield stresses of cement pastes under high hydrostatic pressures. Materials 9(3):147. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9030147

Herschel WH, Bulkley R (1926) Konsistenzmessungen von Gummi–Benzollösungen. Colloid Polym Sci 39(4):291–300

Taylor H (1997) Cement chemistry, 2nd edn. Thomas Telford Publishing, London

de Larrard F, Ferraris CF, Sedran T (1998) Fresh concrete: a Herschel–Bulkley material. Mater Struct 31(7):494–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02480474

Bouras R, Kaci A, Chaouche M (2012) Influence of viscosity modifying admixtures on the rheological behavior of cement and mortar pastes. Korea Aust Rheol J 24(1):35–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13367-012-0004-3

Nehdi M, Rahman MA (2004) Estimating rheological properties of cement pastes using various rheological models for different test geometry, gap and surface friction. Cement Concrete Res 34(11):1993–2007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.02.020

Casson NA (1957) flow equation for pigment-oil suspensions of printing ink type. In: IRheology of disperse systems. Proceedings of the conference of the British Society of Rheology, University College, Swansea, Pergamon, London, pp 84–102

Güllü H (2015) On the viscous behavior of cement mixtures with clay, sand, lime and bottom ash for jet grouting. Constr Build Mater 93:891–910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.05.072

Talero R, Pedrajas C, Rahhal V (2013) Performance of fresh Portland cement pastes–determination of some specific rheological parameters. In: Durairaj R (ed) Rheology—new concepts, applications and methods. IntechOpen, Rijeka, pp 57–79

Peng J, Deng D, Liu Z, Yuan Q, Ye T (2014) Rheological models for fresh cement asphalt paste. Constr Build Mater 71:254–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.08.031

Papo A, Piani L (2004) Flow behavior of fresh Portland cement pastes. Part Sci Technol 22(2):201–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/02726350490457277

Vikan H, Justnes H, Winnefeld F, Figi R (2007) Correlating cement characteristics with rheology of paste. Cement Concrete Res 37(11):1502–1511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2007.08.011

Banfill P (2006) Rheology of fresh cement and concrete. Rheol Rev 2006:61–130

Güllü H (2016) Comparison of rheological models for jet grout cement mixtures with various stabilizers. Constr Build Mater 127(Supplement C):220–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.09.129

Vom Berg W (1979) Influence of specific surface and concentration of solids upon the flow behaviour of cement pastes. Mag Concrete Res 31(109):211–216. https://doi.org/10.1680/macr.1979.31.109.211

Papanastasiou TC (1987) Flows of materials with yield. J Rheol 31(5):385–404

Mitsoulis E, Abdali S, Markatos N (1993) Flow simulation of Herschel–Bulkley fluids through extrusion dies. Can J Chem Eng 71(1):147–160

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Benyounes, K. Rheological behavior of cement-based grout with Algerian bentonite. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1037 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1089-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1089-9