Abstract

The current study goal is to analyze free vibration behavior of multi-layer composite beams reinforced by graphene platelets resting on viscoelastic foundation. These material properties varies layer to layer in the thickness direction. GPLs are spreaded in each layer randomly and four different distribution patterns are employed and all parameter effects on these four are investigated. Effective material properties are estimated by Halpin–Tsai model and higher order shear deformation beam theory is utilized to achieve the theoretical formulation of multi-layer GPLRC beam and Navier solution have been used to derive and follow up the governing differential equation of motion and natural frequency. To find out the effect of GPLs on composite structures and effect of different distribution pattern of GPLs on frequency of the beam structure and the other parameters, all sections of this study and results are presented based on four GPLs distribution patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Recent researches insisted on applications of different composites in different engineering fields including civil engineering, aerospace, biomedical, and automotive. Also due to recent advancement in science and technology, carbon nanofillers as an important reinforcement in composite structures have shown great potential in constructional engineering due to their preferable mechanical properties [3, 10, 11]; in comparison with carbon nanofillers, graphene or graphene platelets (GPLs) as a reinforcement for composites, have low production cost with high pacific surface areas up to 2630 \({\text{m}}^{2} \;{\text{g}}^{ - 2}\) [2, 7, 24, 25, 30]; graphene platelets with tensile strength of 130 GPA is an appropriate candidate as a reinforcement in composite materials [2, 7, 24, 25, 30]; the other point that convinced researchers to use fillers in composite structures is that subjoining even a poor amount of graphene or other fillers to base material can improve its properties as thermal properties, mechanical properties and electrical too [18, 20, 23,24,25]; so, logically a large part of sections in this project have been allocated to the improvement of material properties with adding even a low amount of GPLs. In order to validate the claim that GPLs improve mechanical properties of composites [19] determined that 0.1% additional (wt%) GPLs in polymer composites improved the different properties of composites such as strength and stiffness. Also Wang et al. [29] achieved that Young’s modulus of epoxy reinforced nanocomposites increases approximately 0.64 GPA by adding 6.0 wt% of GPLs as fillers in the composite plate. Comparing graphene and carbon nanotubes as filler and reinforcement for composite, results showed that graphene has a superior point than Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), such as significant stiffness, supreme strength but low mass density [15]; recently, nanocomposites that reinforced with graphene and its formatives become a widespread topic of researchers; also alumina ceramic composites reinforced with GPLs is studied by Liu et al. [17] and they found that mechanical properties of this composites have been improved too. Ji et al. [12] have been studied the graphene reinforced composites and have been used the Mori–Tanaka model to calculate the effective elastic properties. FEM (finite element method) as a multiscale method have been used by Spanos et al. [28] to achieve atomistic molecular structural mechanics of composites reinforced with graphene. Ji et al. [12] studied the stiffening effect of graphene sheets on polymer nanocomposites and they found that embedding even a low amount of sheets of graphene can extremely increase the effective stiffness of the epoxy matrix. Finite element method is employed to analyze the vibration behavior of composite beams reinforced with graphene platelets (GPLs) [6]; functionally graded carbon nanotube reinforced composite beams with geometric imperfections have been studied by Wu et al. [31]; Thermal buckling analysis of carbon nanotube reinforced composite beams has done too and all important derivatives of structure properties and CNTs effect on composite beams are presented [21, 22]; studying the dynamic behavior of structures based on carbon is used widely in mechanical engineering, recently. Also linear and nonlinear free and forced vibration, bending, elastic buckling, post buckling of composite structures reinforced CNTs have been widely probed [1, 13, 14, 21, 22, 31].

Natural frequencies of polymer composites reinforced graphene have been presented by Chandra et al. [5] using finite element method. Feng et al. [8, 9] also published an article through the nonlinear vibration of multi-layer nanocomposite beam based on Timoshenko beam theory and Von Karman strain–displacement relationship and presented. Bending analysis of polymer nanocomposite beams reinforced with graphene platelets have been studied by Feng et al. [8, 9] and Ritz method employed to reduce the governing differential equation into an algebraic system.

Barati and Zenkour [4] also studied post-buckling behavior of shear deformable graphene platelet reinforced beams with porosities. Kitipornchai et al. [16] presented a project on free vibration and elastic buckling of functionally graded porous beams reinforced by graphene platelets and resulted that graphene platelets are considered as ideal material for composite reinforcements and improved mechanical properties of composite structures. Shabanlou et al. [26] used finite element method to study free vibration behavior of multi-layer composite beams reinforced GPLs.

No work has been done at vibration analysis of multi-layer GPLRC beams resting on viscoelastic foundation using higher order shear deformation beam theory whereas non-uniformly distributed different GPL patterns are considered. Recent researches focused on the nanocomposites construction and their material properties but present study has been analyzed the vibrational behavior of multi-layer GPLRC beam resting on two parameter viscoelastic foundation considering effects of four different distribution patterns on mechanical parameters of GPLRC beams in detail.

2 Problem formulation

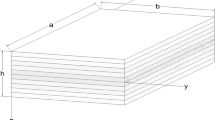

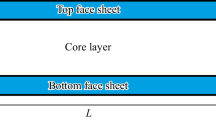

As shown in Fig. 1 four different types of GPLs distribution of multi-layer polymer composite beam with h as thickness dimension and a as length of the beam is considered. \(N_{l}\) is defined the number of layers of GPLRC beam with equal amount of thickness for every layer of the beam structure \(\left( {\Delta h = \frac{h}{N}} \right)\). To form a functionally graded structure, the GPLs weight fraction is varied layer to layer based on Eqs. (1)–(4). As shown in Fig. 2 four different distribution pattern are considered which pattern 1 is an isotropic homogeneous beam case that GPLs (wt% of GPLs 1%) are regularly distributed at every individual layer. Pattern 2 presented GPL weight fraction (wt%) changes layer to layer along the thickness, as shown in Fig. 2. In the other words, GPLs weight fraction is the highest in the mid-plane and is decreased layer to layer when it moves to the top and bottom layer in pattern 2. In contrast to pattern 2, in pattern 3 both top and bottom layers are consisting the maximum weight fraction of GPLs and changes to the lowest by moving to the mid-plane while pattern 4 is non-symmetrical pattern and linear increasing is shown in Fig. 2 for GPLs weight fraction from top to the bottom surface.

The volume fraction functions of these four GPL distribution pattern have been represented as [27]:

where k is number of GPLRC beam layers, \({\text{k}} = 1,2 \ldots ,N_{l}\) and \(V_{GPL}^{*}\) is the total volume fraction of GPLs.

3 Effective material properties

Based on Halpin–Tsai model, the effective elastic modulus of GPLRC approximated by [27]:

where E is effective modulus of GPLRC and \(E_{L}\) is the longitudinal modulus for unidirectional laminate calculated by the Halpin–Tsai model and \(E_{T}\) is the transverse mudulus of laminate.

where

where \(l_{GPL }\), \(h_{GPL}\), \(w_{GPL}\) are GPLs dimensions.

By using rule of mixture, Mass density \(\rho_{c}\) and Possion’s ratio \(\nu_{c}\) of the GPL/nanocomposite is presented as [27]:

where \(V_{M}\) is the volume fraction of epoxy matrix.

The governing equation of \(V_{GPL}^{*}\) is:

where \(W_{GPL}\) is GPL weight fraction; \(\rho_{GPL}\) and \(\rho_{M}\) are the mass densities of GPLs and the epoxy matrix.

4 Governing equation

Based on the higher-order shear deformation theory the displacement of beam along x, \(y\) and z direction are represented as:

where \(c_{1}\) is equal to \(4/3h^{2}\) and where u and v are the in-plane displacements at anypoint (x, y, z) and \(u_{0}\) define the in-plane displacement of the point (x, y, 0) on the mid-plane, w is the deflection, and \(\phi_{x}\) is the rotation of the normals to the mid-plane about x axes.

From the linear elastic stress–strain constitutive relationship, the stress matrix of the multi-layer GPLRC beam is presented as:

Based on Hamilton principal:

Work done by viscoelastic foundation is:

where \(K_{p}\) and \(K_{w}\) are Pasternak and Winkler coefficient.

External work done by damper is presented as:

Finally governing equation of GPLRC with the effect of viscoelastic foundation resulted in:

where parameters used in the above equation are defined as:

where \(\rho^{k}\) is the mass density of kth layer of GPLRC beam.

5 Solution procedure

Navier solution is used to continue solution procedure:

where \(U_{mn}\), \(W_{mn}\) and \(X_{mn}\) are dimensionless functions of time and m and n are defined as mode number of vibration of GPLRC beam.

The boundary condition equation of simply supported beam in all edges can be written as:

So matrixes resulted by solving governing equations based on Navier solution are:

By setting the determinate of above matrixes equal to zero, answers are leaded us to the vibration analysis of GPLRC beam.

6 Results and discussion

A complete research is done at multi –layer polymer beam reinforced by graphene platelets resting on viscoelastic foundation in the present study. The material properties of the matrix are given as:

Non-dimensional natural frequency of multi-layer GPLRC beam is given as follow:

The material properties of the GPL as a reinforcement and epoxy are given in Table 1:

6.1 Effects of elastic foundation on dimensionless frequency parameter (\(\lambda\))

Variation of Winkler and Pasternak foundations coefficient is presented in this part and vibration behavior of GPLRC beam is studied in detail. Also all four GPLs distribution patterns and polymer matrix without any reinforcement are determined and the point is that in all patterns by increasing elastic coefficient (\(K_{w}\) and \(K_{p}\)),dimensionless frequency of the beam structure is shincreasing as shown in Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7. In Fig. 3 beam is studying without any reinforcement and by increasing Winkler factor to 3 N/m, dimensionless natural frequency presented an increasing process but when Winkler factor overpassed 3 N/m, the frequency is leaded to constant amount and is continued to the end. By adding GPLs to the structure and studying the effects of Pasternak factor on vibration analysis of GPLRC beam, results showed that dimensionless frequency of the structure is increasing by Pasternak factor increasing.

It is clear that results derived, insisted on increasing process of dimensionless frequency of the structure by Winkler and Pasternak coefficient increasing in all four distribution pattern. Figure 4 presented variational diagram of pattern 1 which homogeneous distribution is governed. By two parameter elastic foundation increasing, frequency amount is started from 0.28 and leaded to 0.3.

Comparing Figs. 3 and 4 have shown difference between layer-wise distribution and uniform distribution. Frequency of GPLRC beam is started increasing process from smaller amount but is continued like pattern 1.

Pattern 3 and 4 also are presented increasing diagram of dimensionless frequency. In pattern 3 where more GPLs weight fraction spread out in outer layers, increasing process for dimensionless frequency is started from more numerical amount. Comparing pattern 3 and 4, multi-layer GPLRC beam resting on elastic foundation, these two patterns have shown increasing diagram but in Pattern 4 where GPL weight fraction changes layer to layer as moving to upper layers, increasing process is started from smaller amount.

6.2 Effects of damper on natural frequency of multi-layer GPLRC beam

In this section, studying the effects of elastic foundation on the vibrational behavior of the structure has done and \(K_{w}\) and \(K_{p}\) as Winkler coefficient and Pasternak coefficient and \(C_{d}\) as damper coefficient are determined. All four GPL distribution patterns are considered to analyze the vibrational parameters of the structure accurately. Based on Table 2 an increasing procedure for the natural frequency of beam is derived by increasing the amount of \(K_{w}\) and \(K_{p}\). Also, results insisted on bigger amount of natural frequency for pattern 1 which GPLs are spreading homogeneous in all layers and the weight fraction of this nanofillers are same at all layers of beam than pattern 2 which the amount of GPLs weight fraction are changing linearly (middle layers included the most weight fraction of GPLs). In this table by varying numerical amount of Pasternak coefficient, it is clear that in constant Winkler coefficient, by increasing \(K_{p}\), natural frequency is increased too. Comparing pattern 1 and 2 emphasized on bigger amount of frequency for pattern 1 than pattern 2 in the same amount of \(K_{p}\).

6.3 Effects of damper on dimensionless frequency of GPLRC beam

Damper coefficient increasing is investigated in this part and effects of \(C_{d}\) on GPLRC beam vibrational behavior in constant elastic factors is shown in Fig. 8. By varying \(C_{d}\) to bigger amount, dimensionless frequency is constant at first but by leading to bigger amount of this coefficient, decreasing process in all four patterns is resulted. \(C_{d}\) as damper factor is varying from 0 to \(3 \times 10^{6} \;{\text{Ns/m}}\).

Numerical results of dimensionless frequency of GPLRC beam in different amount of \(C_{d}\) is presented by Table 3 (GPL weight fraction amount is 0.12). Results is showed that by leading damper factor to bigger number, dimensionless frequency of the structure is showed decreasing process in all patterns.

7 Conclusions

-

1.

Increasing damper coefficient resulted in smaller amount of dimensionless natural frequency in all four GPL distribution and pure epoxy (Table 3).

-

2.

By varying \(C_{d}\) to bigger amount, dimensionless frequency is constant at first but by leading to bigger amount of this coefficient, decreasing process in all four patterns is resulted (Fig. 8).

-

3.

In constant Winkler coefficient amount, by \(K_{p}\) increasing, the natural frequency is increased (Table 2).

-

4.

By increasing the amount of \(K_{w}\) and \(K_{p}\) the natural frequency of GPLRC beam is increased too in all four patterns (Table 2).

-

5.

By adding GPLs to the structure and studying the effects of Pasternak factor on vibration behavior of GPLRC beam, results is showed that dimensionless frequency of the structure is increased by Pasternak factor increasing (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7).

-

6.

By varying numerical amount of Pasternak coefficient, it is clear that in constant Winkler coefficient, by \(K_{p}\) increment, natural frequency is increased too (Table 2).

References

Ansari R, Hasrati E, Shojaei MF, Gholami R, Shahabodini A (2015) Forced vibration analysis of functionally graded carbon nanotube-reinforced composite plates using a numerical strategy. Phys E Low Dimens Syst Nanostruct 69:294–305

Balandin AA, Ghosh S, Bao W, Calizo I, Teweldebrhan D, Miao F, Lau CN (2008) Superior thermal conductivity of single-layer graphene. Nano Lett 8(3):902–907

Baradaran S, Moghaddam E, Basirun WJ, Mehrali M, Sookhakian M, Hamdi M, Moghaddam MN, Alias Y (2014) Mechanical properties and biomedical applications of a nanotube hydroxyapatite-reduced graphene oxide composite. Carbon 69:32–45

Barati MR, Zenkour AM (2017) Post-buckling analysis of refined shear deformable graphene platelet reinforced beams with porosities and geometrical imperfection. Compos Struct 181:194–202

Chandra Y, Chowdhury R, Scarpa F, Adhikari S, Sienz J, Arnold C, Murmu T, Bould D (2012) Vibration frequency of graphene based composites: a multiscale approach. Mater Sci Eng B 177(3):303–310

Chu NH, Feng C, Yang J, Kitipornchai S (2017) Finite element analysis on free vibration of polymer composite beams reinforced with graphene platelets. In: Mechanics of structures and materials: advancements and challenges—proceedings of the 24th Australasian conference on the mechanics of structures and materials, ACMSM24 2016. CRC Press, Balkem, pp. 1803–1808

Du X, Skachko I, Barker A, Andrei EY (2008) Approaching ballistic transport in suspended graphene. Nat Nanotechnol 3(8):491

Feng C, Kitipornchai S, Yang J (2017) Nonlinear free vibration of functionally graded polymer composite beams reinforced with graphene nanoplatelets (GPLs). Eng Struct 140:110–119

Feng C, Kitipornchai S, Yang J (2017) Nonlinear bending of polymer nanocomposite beams reinforced with non-uniformly distributed graphene platelets (GPLs). Compos Part B Eng 110:132–140

Gauvin F, Robert M (2015) Durability study of vinylester/silicate nanocomposites for civil engineering applications. Polym Degrad Stab 121:359–368

Huang X, Qi X, Boey F, Zhang H (2012) Graphene-based composites. Chem Soc Rev 41(2):666–686

Ji XY, Cao YP, Feng XQ (2010) Micromechanics prediction of the effective elastic moduli of graphene sheet-reinforced polymer nanocomposites. Model Simul Mater Sci Eng 18(4):045005

Ke LL, Yang J, Kitipornchai S (2013) Dynamic stability of functionally graded carbon nanotube-reinforced composite beams. Mech Adv Mater Struct 20(1):28–37

Ke LL, Yang J, Kitipornchai S (2010) Nonlinear free vibration of functionally graded carbon nanotube-reinforced composite beams. Compos Struct 92(3):676–683

King JA, Klimek DR, Miskioglu I, Odegard GM (2013) Mechanical properties of graphene nanoplatelet/epoxy composites. J Appl Polym Sci 128(6):4217–4223

Kitipornchai S, Chen D, Yang J (2017) Free vibration and elastic buckling of functionally graded porous beams reinforced by graphene platelets. Mater Des 116:656–665

Liu J, Yan H, Jiang K (2013) Mechanical properties of graphene platelet-reinforced alumina ceramic composites. Ceram Int 39(6):6215–6221

Montazeri A, Rafii-Tabar H (2011) Multiscale modeling of graphene-and nanotube-based reinforced polymer nanocomposites. Phys Lett A 375(45):4034–4040

Mortazavi B, Benzerara O, Meyer H, Bardon J, Ahzi S (2013) Combined molecular dynamics-finite element multiscale modeling of thermal conduction in graphene epoxy nanocomposites. Carbon 60:356–365

Potts JR, Dreyer DR, Bielawski CW, Ruoff RS (2011) Graphene-based polymer nanocomposites. Polymer 52(1):5–25

Rafiee M, Yang J, Kitipornchai S (2013) Large amplitude vibration of carbon nanotube reinforced functionally graded composite beams with piezoelectric layers. Compos Struct 96:716–725

Rafiee M, Yang J, Kitipornchai S (2013) Thermal bifurcation buckling of piezoelectric carbon nanotube reinforced composite beams. Comput Math Appl 66(7):1147–1160

Rafiee MA, Rafiee J, Srivastava I, Wang Z, Song H, Yu ZZ, Koratkar N (2010) Fracture and fatigue in graphene nanocomposites. Small 6(2):179–183

Rafiee MA, Rafiee J, Wang Z, Song H, Yu ZZ, Koratkar N (2009) Enhanced mechanical properties of nanocomposites at low graphene content. ACS Nano 3(12):3884–3890

Rafiee MA, Rafiee J, Yu ZZ, Koratkar N (2009) Buckling resistant graphene nanocomposites. Appl Phys Lett 95(22):223103

Shabanlou G, Hosseini SAA, Zamanian M (2017) Vibrations analysis of FG spinning beam using higher order shear deformation beam theory in thermal environment. Appl Math Model 56:325–341

Song M, Kitipornchai S, Yang J (2017) Free and forced vibrations of functionally graded polymer composite plates reinforced with graphene nanoplatelets. Compos Struct 159:579–588

Spanos KN, Georgantzinos SK, Anifantis NK (2015) Mechanical properties of graphene nanocomposites: a multiscale finite element prediction. Compos Struct 132:536–544

Wang Y, Yu J, Dai W, Song Y, Wang D, Zeng L, Jiang N (2015) Enhanced thermal and electrical properties of epoxy composites reinforced with graphene nanoplatelets. Polym Compos 36(3):556–565

Wei X, Lee C, Kysar JW, Hone J (2008) Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science 321(5887):385–388

Wu H, Kitipornchai S, Yang J (2015) Free vibration and buckling analysis of sandwich beams with functionally graded carbon nanotube-reinforced composite face sheets. Int J Struct Stab Dyn 15(07):1540011

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Qaderi, S., Ebrahimi, F. & Seyfi, A. An investigation of the vibration of multi-layer composite beams reinforced by graphene platelets resting on two parameter viscoelastic foundation. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 399 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-0252-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-0252-7