Abstract

Structural layout design of blended wing body (BWB) aircraft in the preliminary design phase is a challenging optimization problem due to large numbers of design variables and various constraints. A two-loop optimization strategy is proposed to solve the BWB aircraft structural layout design problem considering constraints of the displacement, stress, strain, and buckling. The two-loop optimization consists of an inner loop and an outer loop. The inner loop is to optimize each stiffened panel of the BWB aircraft structure, and outer loop is to find the best layout design. To improve computational efficiency, an equivalent finite element model is applied to BWB aircraft structure analysis, and an analytical method is used for buckling and static analysis of the stiffened panels. The proposed method can efficiently solve the structural layout optimization problem of a notional BWB aircraft with acceptable computational burden. The result indicates the mass of main load-carrying structure of the BWB aircraft is reduced by 9.28% compared to that of the initial structural layout.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the past decades, there has been great interest in improving the performance of transport aircraft for the reductions in fuel burn, noise and NOx emissions [1]. Non-conventional aircraft concepts, such as the BWB (blended wing body) aircraft, have been proposed for revolutionary improvement for future air transportation while the current generation civil transports cannot fulfill those requirements [2]. The BWB aircraft is a tailless design concept that integrates wing and fuselage. The main aerodynamic advantage of the BWB design is its lower wetted area to volume ratio and lower interference drag compared to the conventional aircraft, which may lead to large fuel savings and offer superior operating economics [3,4,5].

Since BWB is an unconventional configuration concept, there is a lack of experience and empirical data in the structural design of BWB aircraft. The BWB structural design study is needed to explore its structural mass benefits or penalties. Several studies on structural design optimization of BWB aircraft have been conducted. Gern [6] developed a software tool to rapidly generate finite element model for structural optimization and mass prediction of BWB aircraft. The tool was written as a Matlab script that reads in user-provided data to generate a set of MSC Nastran input files for analysis and optimization. Li and Kim [7] studied a detailed BWB structural finite element model that featured the aircraft’s fuselage skins, frames, ribs, spars, floors, movable control surfaces, high-lift devices, and bulkheads. The total number of elements in the model was approximately 44,000, representing more than 142,000 degrees of freedom, and a two-stage global–local optimization approach was implemented. Hansen and Horst [8] proposed a two-level optimization strategy for typical parts of the BWB aircraft fuselage structure. In their study, single skin, double skin and sandwich structural design optimization under multiple loads and constraint conditions were investigated.

The above studies for BWB aircraft structure mainly focused on the dimension (size) optimization, but structural layout design for BWB aircraft was not investigated. Since the structural layout has a large impact on the mass and stiffness of aircraft structure and, moreover, there is still lack of knowledge available on the optimal structural layout for BWB aircraft, layout optimization for BWB aircraft structure design is needed to be investigated. Singh and Toropov [9] applied topology optimization to layout design of BWB aircraft, and the reasonable structural layout of the BWB passenger aircraft was obtained. However, in their study the design constraints such as buckling were not included and structural materials were limited to metals. From views of aircraft structural design practice, inclusion of buckling constraints in structural layout optimization is necessary. The optimal structural layout design obtained by the method without buckling constraints might be very different with the design from the method with buckling constraints. Furthermore, use of composite materials in structure is essential for advanced BWB concept. Our literature survey indicates that there is little study on BWB aircraft structural layout optimization that includes buckling constraints and deals with composite materials.

In this paper, we attempt to propose an efficient method for structural layout optimization, which is expected to be used practically in preliminary structural design of BWB aircraft. In our method, structural constraints of stress, strain, deformation, and buckling are included and composite material is considered. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. A notional BWB aircraft design concept and structural optimization problem will be described in Sect. 2. A layout optimization method solving the BWB aircraft structural design problem will be presented in Sect. 3. The optimization results from the layout optimization method will be presented and discussed in Sect. 4, and followed by conclusions in Sect. 5.

2 Description of Optimization Problem

2.1 Notional BWB Aircraft

A notional BWB passenger aircraft with 450 seats is used as an example for structural layout optimization study in this study. The configuration of the BWB aircraft is illustrated in Fig. 1 and the primary parameters for the BWB aircraft are presented in Table 1. As shown in Fig. 1, the BWB aircraft can be broken down into three main sections: a pressurized centerbody (fuselage), inboard wing and outer wing. The leading edge sweep angles for the centerbody and the outer wing are 57° and 36°, respectively. The average value of thickness to chord ratio of the centerbody is around 17% and the thickness to chord ratio distribution is averagely 9% on the outer wing. The inboard wing blends the thick centerbody with the thin outer wing with a large variation in its thickness.

2.2 Initial Structural Layout

The initial structural layout of the BWB aircraft is illustrated in Fig. 2.

The centerbody of BWB aircraft has in general a large width considering the constraints of comfort and evacuation. The BWB centerbody is the most unique airframe since the airframe has the unusual loading pattern (i.e. fuselage-bending loads, wing-bending loads and the cabin overpressurization), which leads to high bending loads in the upper and lower skins. To eliminate high bending loads, the fuselage-stiffened panels that are made up of skins, stringers and frames are designed as a bi-directionally stiffened panel, where the wing-bending loads are carried by the frame members and the fuselage-bending loads are carried by the stringers [10]. The resulting panel design is beneficial for reduction of the mass penalty. Large internal walls are used to divide the cabin bays and decrease the span distance. By decreasing the span distance, this additional support decreases the bending moments induced from resisting the internal pressure [11]. Cabin floor is positioned based on desired cabin height, and the rear spar in centerbody is specified as bulkheads. The main frames are attached to multi-spars [12] and the pressure loads are carried by a bending-resistant structure (i.e. normal frames). The aft-body section is not pressurized and consists of upper and lower skin, and aft-body substructure.

The inboard wing structure blends the centerbody with outer wing, and consists of multiple spars, ribs, and upper and lower stiffened panels. Front and rear spars provide continuous load paths from the outer wing to the centerbody cabin. Intermediate spars are inserted if the interval between the two middle spars is larger than some specified allowance. Middle spars connect the front spar of the outer wing to the side wall of the centerbody. All ribs in the inboard wing are oriented in the stream-wise direction.

The structure layout of the outer wing is similar to that of conventional aircraft wing, which consists of a front spar, a rear spar, upper and lower stiffened wing panels, and evenly spaced ribs. And the ribs are perpendicular to the rear spar, thus the rib length is shorter and its mass can be reduced [13].

Basically, BWB aircraft structure consists of a large number of stiffened panels composed of skin and stringers. The stringers in centerbody and inboard wing are oriented in the span-wise direction, and stringers in outer wing are parallel to the outboard rear spar.

2.3 Structural Materials

The BWB aircraft is designed with advanced composite materials for both primary and secondary structures. The composite sandwich frame whose stacking sequence of face sheet is a symmetry orientation [± 45°, 0°, 90°]s is built with composite fabric wrapped around the long foam core [14, 15]. The bulb-stiffened panel [16] using composite material is applied to the load-carrying structure and the stringers or stiffeners in bulb-stiffened panel consist of webs with a unidirectional carbon fiber rod at the top of the web. All of structural components, such as skins, spars, ribs and stringers or stiffeners, are made of composite laminates with eight layers and a symmetry orientation [± 45°, 0°, 90°]s. Floor structures are made of isotropic aluminum materials [17]. The material properties used in this study are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

2.4 Loads

The loads considered in this study include the aerodynamic load and inertia loads from mass distributions. The load case is the 2.5-g flight maneuver with a safety factor 1.5. The aerodynamic load is computed by the in-house code [18] which is developed based on the potential flow. The masses that are considered in structure analysis include masses of payloads and fuels, mass of the BWB aircraft structure, and masses of landing gears and engines. The payloads are located in the centerbody and fuel tanks are located in the inboard wing and outer wing sections [19], as depicted in Fig. 3.

2.5 Formulation of Structural Layout Optimization

The structural layout of the BWB aircraft is defined by a set of parameters such as rib spacing, stringer spacing, interval of frames and spar location, which will be illustrated in detail in Sect. 3.1. Usually, change of structural layout parameters results in change of the stiffened panel sizes and mass. For example, the ribs provide support for the stiffened panels and rib spacing affects the global buckling of the panels. If the rib spacing (a parameter of the structural layout) is changed, the sizes of stiffened panels will be changed to satisfy requirement of the buckling load factor. Consequently, those changes lead to change of mass of entire BWB aircraft structure. The aim of structural layout optimization is to find a set of structural layout parameters which lead to the minimum mass of the stiffened panels in BWB aircraft structural design.

The initial structural layout (Fig. 2) might not be optimal in terms of structural mass reduction. Optimization method will be applied to find a better structural layout for the BWB aircraft. The structural design problem of the BWB aircraft can be formulated as follows in term of optimization.

- Objective::

Minimize mass of the BWB aircraft structure

- Design variable::

There are two kinds of the design variables: (1) design variables for structural layout, and (2) design variables for the stiffened panel sizes. The structural layout design variables include rib and stringer spacing, intervals of the frames and locations of the spars, and will be defined in more detail in Sect. 3.1. The design variables of the stiffened panel sizes include the thickness of skins and stringer web, and height of stringers. Detailed geometry for the stiffened panel will be presented in Sect. 3.3

- Constraints::

The structure must be satisfied with allowable stress and strain of materials, limitation of the structural deformation, and allowable buckling factor

The above optimization problem has a large number of design variables including design variables for structural layout and design variables for stiffened panel sizes, and has varieties of constraints. An initial attempt using conventional optimization method failed to solve the above optimization problem due to unacceptable computational burden. To solve this problem in more practical and efficient way, we propose a layout optimization method that will be presented in next section.

3 Layout Optimization Method

Theoretically, topological optimization methods can be applied to layout design [20]. But those methods have difficulties dealing with the buckling constraints and composite materials in layout optimization of BWB aircraft structure.

In this study, we propose a more straightforward strategy for layout optimization of BWB aircraft structure. The procedure of proposed method is shown in Fig. 4, which consists of an inner loop and an outer loop. The function of the inner loop is to compute structural mass through panel optimization for a given layout design, and the function of the outer loop is to find best values of layout design variables with minimum structural mass. In this manner, the layout optimization problem with a large number of variables is now transformed into the optimization in the inner loop and the optimization in the outer loop. In the inner loop, the optimization problem for each stiffened panel is very simple and can be solved with small computation expense. The optimization in the outer loop can be completed in reasonable computing expense because of small computation expense in the inner loop.

The procedure starts with BWB aircraft structural layout definition by a given values of layout design variables, and output of the procedure is optimal structural layout design. Each step of the procedure in Fig. 4 will be detailed as follows.

3.1 Definition for Structural Layout

The structural layout is defined by a set of parameters, in which a subset of the parameters is used as the design variables for structural layout optimization.

Generally, the most efficient structure can be achieved by adjusting layout design variables (rib spacing, stringer spacing, interval of frames, and spar location) in preliminary design phase. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the design variables of structural layout optimization are rib spacing (b1 and b2), upper and lower stringer spacing in wing section (L1 and L2), intervals of frames (F1 and F2), and locations of front and rear spar (S1, S2, S3 and S4: the percentages of the local chord). The stringers run through the entire wing span, and each stiffened panel has the same rib spacing. The spar location and intervals of internal walls in centerbody section are not considered as the design variables because those parameters are set by cabin layout sized by the number of passengers or amount of cargo. The bending and the torsional stiffness of the entire BWB aircraft are assumed to mainly depend on the main load-carrying structures. Thus, the leading and trailing edge are not considered in the layout optimization.

3.2 Parametric Geometry Model of Structural Layout

Since the structural layout will be updated in the outer loop, the geometric model of the BWB aircraft structural layout needs to be generated automatically when the values of structural layout design variables are changed. The automatic generation of the structural layout geometric model is implemented in MSC Patran using PCL (Patran command language). An example of the structural layout geometric model generated in this manner is illustrated in Fig. 5. When the values of structural layout design variables are changed, the geometric model will be changed accordingly.

3.3 Generating Finite Element Model

The structure defined by the above geometric model will be analyzed by finite element method in structure analysis software MSC Nastran. When the generation of the structural layout geometric model is completed, a finite element (FE) model can be generated automatically using the PCL [21].

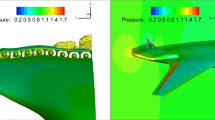

In the FE model, spar webs, rib webs, frame webs, floors and stiffened skin panels are mainly modeled by quadrilateral elements with shell properties, and triangular elements are used in transition areas (green area in Fig. 6). Axial rod elements are used to represent spar flanges, the caps of frames and ribs. The direct modeling of stringer or stiffeners in the structural FE model leads to complicacy, and automatic generation of the structural FE model might be not robust. Thus, the stringers of the stiffened panels are not directly modeled but rather their stiffness properties will be represented by an equivalent shell element [22]. Figure 6 shows the structural FEM model for the BWB aircraft structure.

Simplifying the stiffened panel with equivalent panel can significantly decrease the scale of FE model. Without the complex shapes of stringers, equivalent panel can efficiently simulate global buckling modes. Figure 7 shows the detailed stiffened panel model and its equivalent panel model.

The stiffness of equivalent panel can be described as the superposition of skin’s stiffness and stiffeners’ stiffness. Thus, the equivalent matrix of the entire panel can be obtained by assembling the stiffness matrixes of skins and stiffeners, which can be calculated by

where Ask, Bsk and Dsk are in-plane, coupling and bending stiffness coefficient matrices of skin and Astr, Bstr and Dstr are in-plane, coupling and bending stiffness coefficient matrices of a stringer [23, 24].

3.4 In-Plane Load Extraction

Once the FE model of BWB aircraft is generated, the structural analysis can be carried out. Then, the in-plane load of the stiffened panel will be extracted as applied loads for the panel optimization.

The aerodynamic loads usually generates bending and twist moments on the main load-carrying structures, and causes upper stiffened panels to bear in-plane compression and shearing loads, and lower stiffened panels to bear tension and shearing loads. Based on this load case, the stiffened panels carry combined in-plane loads including axial loads and shear loads.

Generally, the in-plane axial load Fxi(y) and shear load Fsi(y) extracted from the FE model are not the uniform load as shown in Fig. 8 and the nonuniform load need to be unified using the following equation:

where Fx and Fs are the uniform load of the axial load and shear load.

Moreover, the equivalent panel from the FE model is usually trapezoidal plate and needs to be transformed into a rectangular plate [22] for the reason that the theoretical analysis of the composite mechanics is based on a rectangular plate, as shown in Fig. 8.

3.5 Optimization for Each Stiffened Panel

After the FE model is generated and in-plane load is extracted, the sizes of each stiffened panel will be determined by panel optimization. The panel optimization is formulated as follows.

- Objective::

Minimize the mass of each stiffened panel

- The design variables::

The thickness of the skin, and the thickness and height of the stringer of each stiffened panel

- The constraints::

The global buckling factor, eglo ≥ 1.0, the local buckling factor, eloc ≥ 1.0, and the static failure factor, estatic ≥ 1.0 under the compression and shear

A sequential quadratic programming (SQP) is used to solve the above optimization problem. The key point in the optimization for each stiffened panel is computation of the global buckling factor, eglo, local buckling factor, eloc, and the static failure factor, estatic. To improve the efficiency of the stiffened panel optimization, an analytical method is used for computation of those factors [24].

Edge boundary condition of the stiffened panel is assumed to be simply supported boundary condition and carrying combined in-plane uniform loads including axial compressive Nx and shearing Nxy. Thus, the buckling loads (Nxcrit under compression and Nxycrit under shear) are given by the following equations, respectively:

where m represent the number of half wave and AR is the aspect ratio (AR = a/b) of the plate. The parameters a and b represent the length and width of the plate. Dij is the bending stiffness of the stiffened panel and the ± sign indicates that buckling can be caused by either positive or negative shear loads.

Stringers are usually cemented or co-cured with skin in composite-stiffened panels, and the skin among two adjacent stringers might be under a boundary case of simply support. So, local buckling of skin also can use formulas described above.

The static allowable axial load Nx-static and allowable shear load Nxy-static of the stiffened panel are:

where εx-allow and εxy-allow represent the allowable strain under the axial and shear loads, respectively. Aeq is the equivalent axial tensile stiffness of the stiffened panel and A66 is the shear stiffness coefficient of the stiffened panel.

For a combined load case, the interaction curves can be obtained by substituting the global buckling, local buckling, and static failure loads into the following equation:

Interaction curves [25] provide a means for determining: (a) if a stiffened panel fails under combined loads Nx and Nxy; (b) the maximum allowable in one direction (compression or shear) given the applied load in the other. Load combinations inside the interaction curve imply that the stiffened panel does not buckle. Load combinations corresponding to points outside the interaction curve correspond to a stiffened panel that has buckled already.

As shown in Figs. 9 and 10, points M and X represent the global and local buckling loads and the static failure load, respectively. Points N and Y denote the corresponding applied loads. Thus, the global and local buckling factor can be calculated by eglo = eloc = OM∕ON, and the static failure factor is estatic = OX∕OY. When all of eglo, eloc and estatic are greater than 1.0, the stiffened panels will withstand the applied loads without buckling and static failure.

3.6 Deflection Constraint Consideration and Static Failure Coefficient Updating

Since the panel optimization does not consider the deformation constraint, the wingtip deflection of the BWB aircraft needs to be evaluated using the finite element analysis of the entire structure after a panel optimization is completed. The deformation constraint is that the wingtip deflection must be less than 5% of the span of the BWB aircraft. If the wingtip deflection is not satisfied with the constraint, the static failure factor will be updated.

Usually structural stiffness reaches higher levels under more strict strength constraint, thus the increment of the stiffness can be achieved by updating the static strength failure factor by the violated percentage [26], which would be employed as new constraint criteria in the next inner loop. For example, if the wing tip deflection limit of the BWB aircraft is 3 m, while the predicted deflection is 3.6 m, then the limit is violated by 20%. Therefore, the current static strength failure factor is multiplied by 1.2 and uses this failure coefficient as new constraint in the next iteration. The inner loop is iterated until the deformation constraint is satisfied.

3.7 Optimization in Outer Loop

The different structural layout design results in different structural mass computed by the inner loop. The task of the optimization in outer loop is to find the optimal structural layout design with minimal mass. The optimization in outer loop can be formulated as follows:

- Objective::

Minimize the structure mass

- The design variables::

The structural layout design variables (b1, b2, L1, L2, F1, F2, S1, S2, S3 and S4, see Sect. 3.1 for detail definitions)

A multi-island genetic algorithm is used to search the optimal structural layout design. Compared to traditional optimization methods, the genetic algorithm is more likely to find the global optimum. The genetic algorithm uses both crossover and mutation operators which make its population more diverse and thus has the ability to avoid being trapped in a local optima. In theory, the diversity also helps the algorithm to be faster in reaching the global optima since it will allow the algorithm to explore the solution space faster.

4 Optimization Results and Discussion

According to the method of the layout optimization of the BWB aircraft structure presented in the above, a computing framework is implemented in software iSIGHT-FD, as shown in Fig. 11. The entire optimization process can be executed automatically.

The structural optimization of the BWB aircraft in the inner loop (Fig. 4) requires about 20 min on an Intel Xeon E5-2630, (2.6 GHz, 32 GB RAM) for a given structural layout. In the outer loop, 250 structural layouts are generated by the multi-island genetic algorithm. Total computation time for the structural layout optimization of the BWB aircraft is around 3 days.

The iteration history corresponds to the outer loop in the layout optimization which is illustrated in Fig. 12. Each solid circle in the diagram represents one individual out of the populations (25 individuals/generation) while red solid triangles represent the best individual of each generation’s population (total ten generations). The red curve in Fig. 12 shows the reduction of the structural mass over the number of generations. The structural mass decreases rapidly within seven generations, and then decreases slightly and has only small changes.

The layout parameters resulting from the layout optimization are given in Table 4. Comparison between the initial structural layout and optimal one is demonstrated in Fig. 13.

After optimization, we can see that the frames in center areas of centerbody are more densely arranged to carry more loads and resist buckling while the front areas have sparse frames. The front spar is shifted rearward and the rear spar is shifted forward in the outer wing, which shows that the sectional height needs to be increased to make structure more efficient in bending. The stringers along the upper surface are more closely spaced than those on the lower surface in the outer wing for the reason that the wing-bending loads which cause compression at the upper surface are higher than those causing compression at the lower surface. Besides, using the bulb-stiffened panel, the local bending stiffness of the skin increases, the local stability of the skin is enhanced, the structure efficiency is improved, and then the stringer spacing can increase. Moreover, the number of ribs at the inboard wing and outer wing is reduced to reach higher structure efficiency. The structural mass after the layout optimization is reduced by 9.28% compared to that of the initial layout, which implies that structural layout has a large impact on the mass BWB aircraft structure.

The distributions of the thickness of the skins and the areas of stringers after the two-loop optimization are presented in Fig. 14. The thickness of skins and the areas of stringers increase rapidly along the span-wise direction and up to the peak around the kink (the interface of inboard wing and outer wing). Then, they both decrease from the root of the outer wing to the wingtip.

The static and buckling analysis results after the two-loop optimization are illustrated in Fig. 15. It could be seen in Fig. 15 that the kink area carries relative heavy loads, and thus the maximum strain and buckling deformation occur in this area. And Fig. 15 also shows that the results, in which maximum strain is 4360 με, wingtip displacement is 3890 mm, and first-order buckling factor is 1.03, meet all of constraints including stress, strain, deformation, and buckling.

5 Conclusions

To solve the challenging optimization problem of BWB aircraft structural layout design, a two-loop optimization strategy (inner loop and outer loop) is proposed. The inner loop is to optimize the sizes of each stiffened panel of BWB aircraft structure, and outer loop is to find best values of layout design variables. To improve computational efficiency, an equivalent panel model for the BWB aircraft structure and an analytical method for the stiffened panels are used. By use of the equivalent panel model, the FE model of the BWB aircraft structure is simplified significantly without modeling the stiffener. By use of the analytical method, the buckling factor and the static failure factor of the stiffened panels can be computed directly without FE analysis.

According to the two-loop optimization strategy, the FE model of BWB aircraft is utilized only for computation of the in-plane loads of the stiffened panels in each outer loop and evaluation of the deflection of the BWB aircraft structure in the inner loop. Therefore, the structural layout optimization using the proposed strategy does not consume large computational resources. The results from the notional BWB aircraft structural layout optimization indicate that the structural layout parameters have a large impact on the mass BWB aircraft structure, and the structural mass of main load-carrying structure is reduced by 9.28% compared to that of the initial structural layout.

In future study, more load cases will be considered in the BWB aircraft structural layout optimization, and the method proposed in the paper will be applied to the structural mass prediction in BWB aircraft preliminary design.

References

Nickol C, Mcculers L (2009) Hybrid wing body configuration system studies. AIAA Paper 2009-931

Liebeck RH (2004) Design of the blended wing body subsonic transport. J Aircr 41(1):10–25

Qin N, Vavalle A, Moigne AL et al (2004) Aerodynamic considerations of blended wing body aircraft. Prog Aerosp Sci 40(6):321–343

Velicki A, Jegley D (2011) PRSEUS development for the hybrid wing body aircraft. AIAA Paper 2011-7025

Gern FH (2012) Improved aerodynamic analysis for hybrid wing body conceptual design optimization. AIAA Paper 2012-249

Gern FH (2015) Update on HCDstruct—a tool for hybrid wing body conceptual design and structural optimization. AIAA Paper 2015-2544

Li V, Kim L (2015) Hybrid wing body (HWB) aircraft design and optimization using stitched composites. AIAA Paper 2015-2325

Hansen LU, Horst P (2008) Multilevel optimization in aircraft structural design evaluation. Comput Struct 86(1):104–118

Singh G, Toropov V (2016) Topology optimization of a blended wing body aircraft structure. AIAA Paper 2016-3364

Jegley DC, Velicki A (2015) Development of the PRSEUS multi-bay pressure box for a hybrid wing body vehicle. AIAA Paper 2015-1871

Laughlin T, Corman J, Mavris D (2013) A parametric and physics-based approach to structural weight estimation of the hybrid wing body aircraft. AIAA Paper 2013-1082

Hansen LU, Heinze W, Horst P (2006) Representation of structural solutions in blended wing body preliminary design. In: 25th international congress on aeronautical sciences ICAS

Niu MCY (2006) Airframe structural design: practical design information and data on aircraft structures, 2nd edn. Conmilit Press, California, pp 251–256

Mukhopadhyay V (2014) Hybrid-wing-body vehicle composite fuselage analysis and case study. AIAA Paper 2014-2427

Mukhopadhyay V (2012) Hybrid-wing-body pressurized fuselage modeling, analysis, and design for weight reduction. AIAA Paper 2012-1999

Niu MCY (2005) Composite airframe structures: practical design information and data. Conmilit Press, Hong Kong, pp 434–438

Bonet JT, Schellenger HG, Rawdon BK et al (2011) Environmentally Responsible Aviation (ERA) Project—N + 2 advanced vehicle concepts study and conceptual design of subscale test vehicle (STV). NASA/CR 216519

Lyu FX, Xiao TH, Yu XQ (2017) A fast and automatic full-potential finite volume solver on cartesian grids for unconventional configurations. Chin J Aeronaut 30(3):951–963

Ko YYA (2003) The multidisciplinary design optimization of a distributed propulsion blended-wing-body aircraft [Master Thesis]. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Virginia (USA)

Rong JH, Liang QQ (2008) A level set method for topology optimization of continuum structures with bounded design domains. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 197(17):1447–1465

Yang WZ, Yue ZF, Li L et al (2016) Aircraft wing structural design optimization based on automated finite element modelling and ground structure approach. Eng Optim 48(1):94–114

Wang Y, Ou YX, Yin HL, Yu XQ (2016) Structural-optimization strategy for composite wing based on equivalent finite element model. J Aircr 53(2):351–359

Ouyang X, Yu X, Wang Y (2014) Flutter analysis for wing structure using finite element modeling with equivalent stiffness. J Vibroeng 16(3):1483–1493

Zhao Q, Ding YL, Jin HB (2011) A layout optimization method of composite wing structures based on carrying efficiency criterion. Chin J Aeronaut 24(4):425–431

Kassapoglou C (2010) Design and analysis of composite structures: with applications to aerospace structures. Wiley, Chichester, pp 121–138

Collier Research Corporation (2008) HyperSizer pro user manual-automated iteration with finite element analysis. Collier Research Corporation, Newport News, pp 4–7

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 11602103) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, W., Yu, X. & Wang, Y. Layout Optimization for Blended Wing Body Aircraft Structure. Int. J. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 20, 879–890 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42405-019-00172-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42405-019-00172-7