Abstract

COVID-19 is a highly infectious respiratory disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). Starting from Wuhan (China) where it was firstly reported, it rapidly spread to the rest of the world, causing a pandemic with more than 300,000 deaths to date. We report an extremely severe case of coronavirus pneumonia in an over 80-year-old patient with hypertension, coronary heart disease, chronic heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Despite a clearly poor anamnestic and clinical prognostic forecast, she was successfully discharged thanks to a careful evaluation of the case and of the complications that have arisen. Although a higher vulnerability of geriatric patients has been observed, the literature on elderly COVID-19 patients has remained very scarce, especially in those over 80. The article aims to explore factors that may allow the successful outcome and provides important elements to better understand this disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a human coronavirus that causes COVID-19, a highly infectious respiratory disease. From Wuhan (China) where it was firstly reported, it rapidly spread to the rest of the world causing a pandemic [1]. To date, it has caused more than 300,000 deaths [2] showing a higher prevalence in regions with high levels of pollution [3]. It has therefore triggered a great effort by the scientific community to study and identify important information for treatment and prognostic stratification. Herein, we present an interesting case of an extremely severe COVID-19 pneumonia in an 87-year-old woman with several risk factors, bad prognostic indicators, and complex respiratory involvement.

Case Presentation

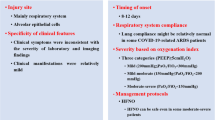

An 87-year-old woman with positive anamnesis for recent femur fracture, hypertension, chronic atrial fibrillation (AF), coronary heart disease, chronic heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease presented to the emergency room with severe dyspnea and cough from 1 week. The patient came from a rehabilitation center within which COVID-19 outbreak occurred. At admission, the patient was afebrile and severe type I respiratory failure was observed: arterial blood gas analysis showed partial arterial oxygen pressure of 46 mmHg at 40% of fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2), (PaO2/FiO2 ratio = 115). Chest high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) showed parenchymal alteration localized to all lung lobes: in particular, multiple areas of ground glass hyperdensities in the context of which several “crazy paving” pattern areas were observed. Large areas of parenchymal consolidation with air bronchogram in the context, with similar distribution, were also present with abundant bilateral pleural effusion (Figs. 1, 2, and 3). Blood exams showed lymphopenia and neutrophilia (L, 750/mm3; N, 14600/mm3), high D-dimer (1100 ng/ml), lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) (383 U/L), and C-reactive protein (CRP) (12.5 mg/dl) plasma levels. Each of the elements mentioned above is recognized in the literature as poor prognostic indicators. Intravenous furosemide and methylprednisolone were administered and non-invasive ventilation (NIV) in CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) modality was initiated. For cardioembolism prevention in relation to chronic AF, oral anticoagulant therapy was replaced with subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin 0.1 IU/Kg bid. After the positive result of the nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 research, lopinavir/ritonavir and hydroxychloroquine were administered. It is important to note that during the first week, lymphopenia worsened and thrombocytopenia appeared. Along 17 days of hospital stay, several complications arose, such as severe dysionemias and psychomotor agitation, but they were successfully treated. At the end of hospitalization, the clinical situation had much improved, with oxygen saturation being 98% in 35% of FiO2 (PaO2/FiO2 ratio = 255) with no dyspnea. Another chest HRTC observed important reduction of ground glass and consolidation areas with onset of reticular pattern and initial fibrosis (Figs. 4, 5, and 6). The patient was therefore transferred to low intensity ward for convalescence.

Conclusions

COVID-19 is a highly infectious respiratory disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), a human coronavirus. This virus was first reported in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, after which, it rapidly spread to the other countries [1] and mostly in regions with higher levels of pollution [3]. In January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Public Health Emergency of International Concern and confirmed as a Pandemic on 11 February [4]. Although nasopharyngeal swab is the diagnostic method recommended by WHO, CT has been given increasing importance with regard to the diagnosis of false negatives [5, 6] and for monitoring the course of the disease and response to therapies [7]. Several efforts have been made to identify therapeutic strategies and prognostic indicators. Among risk factors for mortality in COVID-19 patients, arterial hypertension seems to be the most important one [8]. Laboratory markers that indicate poor outcome are thrombocytopenia [9, 10] and lower lymphocyte counts [11]. High CRP and LDH levels are also important indexes of severe disease: in particular, it was observed that their levels are significantly higher in non-survivors with respect to survivors [12, 13]. It has also been observed that SARS-CoV-2 infection strongly alters coagulation pathway. Non-survivors COVID-19 patients have shown significant higher levels of activated partial thromboplastin times, prothrombin times, and plasma D-dimer levels compared with survivors. In particular, higher D-dimer levels seem to be the strongest independent factor that predicts mortality [14]. Among the anamnestic factors that indicate a poor prognosis, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and pulmonary diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have been clearly identified. Clinical conditions observed at time of admission are also important for prognostic stratification: it has been observed that absence of fever at time of respiratory symptom onset and lower respiratory tract infection symptomatology correlate with poor outcome [15].

Many studies have analyzed how age also plays a key role in mortality. Unlike other infectious lung diseases that have a “U shaped” lethality curve, mortality of novel coronavirus seems to increase in elderly patients [16]. However, although a higher vulnerability of geriatric patients has been observed, the literature on elderly COVID-19 patients has remained very scarce, especially in those over 80. Since the population in China aged 60 or above only accounted for about 6%, there are few studies in over 80 patients which describe the clinical course and the laboratory changes in this category of patients.

Against this picture, we describe an extremely severe case of coronavirus pneumonia in an over 80-year-old patient that recovered despite having all the negative prognostic factors described above, and was successfully discharged thanks to a careful evaluation of the case and of the complications that have arisen. COVID-19 can range from asymptomatic infection to fatal disease with multi-organ failure. The article aims to explore factors that may allow the successful outcome. It was proposed that low-moderate physical activity improves the immune response and clinical outcome [17]. Rehabilitation period that preceded the infection and related physical activity could have positively modulated the immunity against the virus. In fact, immune system role is crucial for natural history of the disease. It was found that development of early adaptive response correlates with a good prognosis [18]. Conversely, low level of CD8 lymphocyte was associated with no protective immunity [19] and low lymphocyte count is a marker of poor outcome [11]. In our patient, during the second week of hospital stay, lymphocytopenia progressively resolved parallel to clinical and radiological improvement. A correlation between normalization of leukocyte formula and recovery can therefore be hypothesized. Hyperinflammation and excessive activation of immune system are also associated with multi-organ damage and high mortality [13, 20, 21]. In this setting, anti-inflammatory effects of heparin in COVID-19 infection have been the object of several studies and it is possible that high dosage of heparin given for cardioembolic prevention played an important role in the good outcome of our case. Various studies highlight that heparin administration is associated with decreased mortality in SARS-CoV-2 infection [22,23,24]. In addition to anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory properties, it was found that it can reduce arrhythmic complication [25], an important cause of death especially in cardiopathic elderly patients [26] like our case. The aim of this paper is to provide important elements to better understand this disease reporting a case that recovered despite the bad prognosis.

References

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–33. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001017.

COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). ArcGIS. Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

Martelletti L, Martelletti P. Air pollution and the novel Covid-19 disease: a putative disease risk factor [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 15. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00274-4.

World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) - events as they happen. 2020. Available at: https://www.whoint/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen. Accessed 20 May 2020.

Xie X, Zhong Z, Zhao W, Zheng C, Wang F, Liu J. Chest CT for typical 2019-nCoV pneumonia: relationship to negative RT-PCR testing [published online ahead of print, 2020 Feb 12. Radiology. 2020:200343. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200343.

Huang P, Liu T, Huang L, Liu H, Lei M, Xu W, et al. Use of chest CT in combination with negative RT-PCR assay for the 2019 novel coronavirus but high clinical suspicion. Radiology. 2020;295(1):22–3. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200330.

National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. The diagnostic and treatment protocol of COVID-19. China. 2020. Available via http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-02/19/content_5480948.htm Accessed 3 Mar 2020.

Lippi G, Wong J, Henry BM. Hypertension in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a pooled analysis. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2020;130(4):304–9. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.15272.

Lippi G, Plebani M, Henry BM. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;506:145–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022.

Mo P, Xing Y, Xiao Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of refractory COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 16. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa270. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa270.

Henry BM. COVID-19, ECMO, and lymphopenia: a word of caution. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4):e24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30119-3.

Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2020 Apr 6;:. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(5):846–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x.

Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ, et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0.

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020 Mar 28;395(10229):1038. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3.

Leung C. Risk factors for predicting mortality in elderly patients with COVID-19: a review of clinical data in China [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 27. Mech Ageing Dev. 2020;188:111255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2020.111255.

Raoult D, Zumla A, Locatelli F, Ippolito G, Kroemer G. Coronavirus infections: epidemiological, clinical and immunological features and hypotheses. Cell Stress. 2020;4(4):66–75. Published 2020 Mar 2. https://doi.org/10.15698/cst2020.04.216.

Matricardi PM, Dal Negro RW, Nisini R. The first, holistic immunological model of COVID-19: implications for prevention, diagnosis, and public health measures [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 2]. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/pai.13271.

Thevarajan I, Nguyen THO, Koutsakos M, Druce J, Caly L, van de Sandt CE, et al. Breadth of concomitant immune responses prior to patient recovery: a case report of non-severe COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(4):453–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0819-2.

Bentivegna E, Sentimentale A, Luciani M, Speranza ML, Guerritore L, Martelletti P. New IgM seroconversion and positive RT-PCR test after exposure to the virus in recovered COVID-19 patient [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 11]. J Med Virol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26160.

Chousterman BG, Swirski FK, Weber GF. Cytokine storm and sepsis disease pathogenesis. Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39(5):517–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-017-0639-8.

Ye Q, Wang B, Mao J. The pathogenesis and treatment of the ‘Cytokine Storm’ in COVID-19. J Inf Secur. 2020;80(6):607–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.037.

Hippensteel JA, LaRiviere WB, Colbert JF, Langouët-Astrié CJ, Schmidt EP. Heparin as a therapy for COVID-19: current evidence and future possibilities [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 10. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00199.2020.

Young E. The anti-inflammatory effects of heparin and related compounds. Thromb Res. 2008;122(6):743–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2006.10.026.

Ayerbe L, Risco C, Ayis S. The association between treatment with heparin and survival in patients with Covid-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 31. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-020-02162-z.

Menezes-Rodrigues FS, Padrão Tavares JG, Pires de Oliveira M, et al. Anticoagulant and antiarrhythmic effects of heparin in the treatment of COVID-19 patients [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 14. J Thromb Haemost. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.14902.

Kochav SM, Coromilas E, Nalbandian A, et al. Cardiac arrhythmias in COVID-19 infection [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 20. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.120.008719.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors materially participated in the research. Dr. Bentivegna participated in data collection and in article preparation. All authors have approved the final article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have any conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

NA.

Registration of research studies

NA.

Guarantor

Prof. Martelletti Paolo, MD.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained by relatives of the patients for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Covid-19

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bentivegna, E., Luciani, M., Spuntarelli, V. et al. Extremely Severe Case of COVID-19 Pneumonia Recovered Despite Bad Prognostic Indicators: a Didactic Report. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2, 1204–1207 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00383-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00383-0