Abstract

Research Question

To what extent do police stop-and-search practices, as captured on officers’ body-worn video cameras, adhere to key dimensions of procedural justice theory, and do levels of adherence vary across the dimensions of (1) citizen participation and voice, (2) neutrality and explanation, (3) respect and dignity and (4) trustworthy motives?

Data

A random sample of 100 recorded stop-and-search encounters was selected from all 601 encounters recorded by Greater Manchester Police between 1st January and 31st August 2017, with an average duration of 12 minutes of combined video and audio with transcripts.

Methods

These records were coded entirely by the first author for the four main dimensions of procedural justice and details about the actors/participants involved. The dimensions were combined into an overall index score of procedural justice for each encounter.

Findings

Most stop-and-searches were characterised by a strong element of police allowing citizens to express voice, followed by police demonstrating respect and offering explanation. The lowest scores were given to “conveying trustworthy motives”. A standardised metric of each element into a measure of 0–100 coded mean scores for participation/voice = 94, explanation/neutrality = 65, respect = 71 and trustworthy motives = 47. In this latter category, not one officer linked the purpose of the stop and search to the wider organisational purpose of protecting society and helping to keep people safe.

Conclusions

This evidence suggests the potential value of an ongoing tracking measure for police legitimacy which could be used as a supervisory and human development tool for operational officers, comparing individuals, units, areas and trends over time in objectively coded features of police behaviour towards citizens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Stop and search is a well-established police practice that has come under great scrutiny. It is recognised as having been the cause of public discontent and anger when exercised in a way deemed unfair and unjust (Bowling and Phillips 2007). When the police are not believed by the public to be exercising their power or upholding the law in a legitimate way, it can lead to a serious disintegration of law and order. The perceived misuse of the power by police, for example, has been cited as one factor evoking large numbers to take to the streets and riot for four nights in August 2011 across major U. K cities (Lewis et al. 2011).

Set against this context, policing in the UK simply cannot afford to get stop and search wrong. Yet an inspection into police use of stop and search by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS 2013) raised concerns that

“given that the police use of stop and search powers has been cited as a key concern for police legitimacy and public trust in most of the major public inquiries into policing since the 1970s, it is surprising that it has not been afforded higher priority by chief officers” (HMICFRS 2013 p.8).

Most of the ten recommendations in the HMICFRS report are linked to improving public trust and confidence through enhancing officer understanding and delivery of procedural justice in stop and search encounters. Recommendation 10 is that forces should improve the use of technology to record encounters. The report goes on to examine a case study where police officer body-worn video (BWV) was used to do this.

The present research pursues that method with a much larger sample to gain an understanding of procedural justice in stop and search. Its aim is to show how stop and search could be systematically tracked using objective indicators of the dimensions of the theory.

Research Question

To what extent do police stop and search practices, as captured on officers’ body-worn video cameras, adhere to key dimensions of procedural justice theory, and do levels of adherence vary across the dimensions of (1) citizen participation and voice, (2) neutrality and explanation, (3) respect and dignity and (4) trustworthy motives? That is the central question of this research. Ancillary questions include variability in the answers to this central question across subsets of stop and search encounters.

Data

Unit of Analysis

The unit of analysis used to answer this question is the stop and search encounter as captured on body-worn video. A sampling frame was selected of BWV records from 1st January 2017 to 31st August 2017. In that timeframe there were 601 eligible cases, from which a random sample of 100 BWV recordings was selected with an average duration of 12 min. These videos were stored on Axon Evidence.com. They were exported into Excel and randomised through the “rand” function. From this a random sample of 117 videos was chosen for the study. However, seventeen (17) of those videos did not form part of this study, the reasons for which varied: search of an unoccupied vehicle; technical fault in recording; or the encounter was not a stop and search.

Through systematic viewing of the recorded stop-and-search encounters, the first author coded video/audio records of each encounter according to the four key elements of procedural justice. Each element was given a value in each encounter, which when combined gave an overall procedural justice score. Ultimately, the research created a procedural justice index on a 0–100 scale. These values are based on the coder’s judgement in direct application of theoretical constructs and prior research in procedural justice to the events and dialogue he observed in each encounter.

Coding Excluded

Whilst this study does not look at the issues of racial or ethnic disproportionality or discrimination in selection of persons for stop and search, it recognises the importance placed on these areas by communities, police leaders, numerous policing bodies and the Home Office. In doing so, the study aims to understand how procedurally just the observed stop-and-search encounters were.

Stop-and-search outcomes have also added to the debate about the effectiveness of the use of this power by the police, with a sharp focus on the low arrest rates (Delsol and Shiner 2006; HMICFRS 2013, 2015). In 2013, HMICFRS (2013, p.3) identified that out of the over a million stop-and-search recorded every year since 2006, only 9% resulted in an arrest in 2011/12. Following the HMICFRS inspection of 43 police forces in England and Wales they deemed that in 27% of the 8783 stop-and-search records examined there were insufficient grounds. The HMICFRS re-inspected the 43 forces in 2014/15 to assess progress against the 10 recommendations in conclusion to their 2013 inspection. They concluded that insufficient progress had been made against those recommendations in five areas, some progress had been made in four areas and good progress had been made in only one area, namely better use of technology. In large part, the improvement in technology use can be attributed to the greater availability and subsequent use of body-worn video in stop-and-search encounters. Many forces, including Greater Manchester Police (GMP), have mandated its use in stop and search.

Body-Worn Video

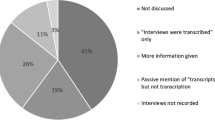

In the mandated areas of domestic abuse and stop and search, the number of video-recorded incidents logged in force is less than the actual number of such incidents dealt with. Based on this gap, it is necessary for the study to be cognisant of the potential for the sample to have suffered from selection bias. Conclusions based on the cases for which cameras were turned on may not be consistent with stop-and-search encounters in which officers failed to record their interactions with citizens.

Over recent years in the GMP area, there has been a steady decrease in the number of recorded stop and searches. The total number of people stopped and searched during the second quarter of 2017–18 was 580, which is a decrease of 118 stop-searches, compared to the previous quarter, and a reduction of 136 stop-searches, compared to the same quarter in 2016–17 (External Relations and Performance Branch 2018). There are many possible reasons for this change that are beyond the scope of the present study, but the decline is well worth noting.

Research Setting

All the stop-and-search encounters analysed as part of this study were conducted by Greater Manchester Police (GMP). The GMP area contains almost 5% of the UK population, with 2,713,000 residents (HMICFRS 2016; Manchester Population 2017) in ten local authority areas. The overall Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) population of the GMP’s area was recorded in the 2011 census data at 16.43% (ONS 2011). The BME population of the GMP area increased by 80% between the 2001 and 2011 census.

Methods

Observational Research by Unobtrusive Measures

Direct observation is a means of achieving more precise measurement and greater insight than can be gained by asking people to describe what they remember about an encounter. ‘Systematic social observation of natural social phenomena’ is a means of achieving greater precision of measurement for a wide range of phenomena, including police-citizen encounters. (Reiss 1971 p.4). The present study, however, diverges from the classic method described by Reiss in which observers are present at the scene as events unfold. By analysing videos recorded at the scene, the observer in this study is unobtrusive (Webb et al. 1966). By not becoming part of the social scene, the observer reduces the risk of influencing the course of the behaviour being observed. Strictly speaking, then, it does not utilise the method of direct observation, recording events as they occur. Observation after the event through a review of the incident captured on BWV is described by Robson (2002), building on Webb et al. (1966), as “non-participatory unobtrusive observation.”

The direct (but non-present) observational approach allows for the present research to describe, analyse and interpret what has been observed. Whereas survey methods ‘are notorious for discrepancies between what people say they have done, or will do, and what they actually did, or will do’, (Robson 2002 p.310), the use of BWV observations provides greater reliability and validity than a survey, interview or questionnaire. The use of only one consistent observer throughout the study arguably strengthens reliability. Yet, it is a limitation of the study that the observer did not undertake test-retest estimation of coding reliability; each encounter was coded only once.

Procedural Justice Coding

The concept of procedural justice was introduced by Thibaut and Walker (1975), who posited that both the perceived fairness of the procedures utilised and the perceived favourability of outcome, independent of each other, will affect a person’s opinion on the overall sense of the fairness with which they are treated (Sahin 2014). The relevant procedures have been identified from a review of the literature by Mazerolle et al. (2013, p16), who distinguish four component parts of procedural justice:

-

1)

‘‘citizen participation in the proceedings prior to an authority reaching a decision (or citizen voice),

-

2)

perceived neutrality of the authority in his/her decision,

-

3)

whether or not the authority showed dignity and respect throughout the interaction and

-

4)

whether or not the authority conveyed trustworthy motives.’’

This fourfold conceptual framework of procedural justice was developed through instruments of measurement by surveys or interviews (Brunson and Miller 2006; Sunshine and Tyler 2003; Tyler and Huo 2002). More recent research studies have measured procedural justice through direct systematic observation. However, there is inconsistency between most of those studies in which elements of procedural justice they measure. Only a few studies measure all four elements identified by Mazerolle et al. (2013). The majority of studies measured only one or two aspects of procedural justice (Jonathan-Zamir et al. 2015).

The present research complements the work of Jonathan-Zamir et al. (2015), who conducted systematic observations with four trained observers observing 233 encounters (of all kinds) in which officers interacted with 319 citizens (Jonathan-Zamir et al. 2015: 849). Their method tracked not the perceptions by citizens, but rather the observable features of procedural justice as defined in the literature.

The present study differs from Jonathan-Zamir et al’s. (2015) work in several ways. One is this study’s inclusion of the element of “explanation.” Another difference is this study’s focus (solely) on stop-and-search encounters, rather than all kinds of encounters. That homogeneity enables more precise measurement and comparative assessment of each encounter for each of the elements of procedural justice.

This focus also allows the legal basis of the police actions to be limited to two primary sources: section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, and section 23 of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. The former allows an officer to search for stolen or prohibited items. Prohibited items include offensive weapons, items to commit criminal damage and prohibited fireworks and items for use in the course of; theft, burglary, taking a motor vehicle without consent. This power allows an officer to detain an individual in a public place for the purpose of conducting a stop and search. Similar provisions of the 1971 Act allow searches for illicit drugs. Whilst there is other legislation that provides the police with stop-and-search powers related to investigating terrorism, firearms possession, serious violence and road traffic matters, none of these powers were exercised by officers in the 100 encounters in the study sample.

Measuring Procedural Justice

This study builds on Jonathan-Zamir et al’s. (2015 p.852) specific indicators of the four elements of procedural justice. In creating their indicators, they reviewed observational studies on procedural justice forming ‘a census of past indicators’. Only a small number of those studies reviewed covered all four elements of procedural justice.

The indicators used in this study were designed specifically for assessing procedural justice in a stop-and-search encounter. The majority of indicators have a binary assessment of yes or no, although some have a graded assessment.

-

1)

Citizen Participation

Voice:

-

Evidence that the officer actively sought the citizen’s viewpoint – Yes/No.

-

Evidence that the citizen provided their viewpoint – Yes/No.

-

Evidence that the officer listened to the citizen – Yes/No.

Quality of officer listening:

-

0 = dismissive listener; 1 = inattentive listener; 2 = passive listener; 3 = active listener.

-

Did the officer interrupt the citizen: Yes/No.

-

2)

Explanation/Neutrality

When an officer complies with the legal requirements in explaining both (a) the reasons for a stop and search together with (b) the citizen’s rights, this would make the officer's decision-making process more transparent. Consequently, this would assist in any assessment of the officer’s level of objectivity in reaching the decision to stop and search. The coding of this element is assisted by a widely used mnemonic called “GOWISELY”. Officers must comply with each element of this mnemonic when undertaking stop and search encounters in line with the PACE statute Code A and College of Policing guidance (2015), in which the first letter of each of these points remind officers to act upon them:

-

a.

Grounds for search – a clear explanation of the officer’s grounds for suspicion.

-

b.

Object of search – a clear explanation of the item(s) the officer is looking for.

-

c.

Warrant card (if not in uniform or requested).

-

d.

Identity of officer – the officer’s name and number.

-

e.

Station to which the officer is attached.

-

f.

Entitlement to a copy of the search record (i.e. within 3 months).

-

g.

Legal power used.

-

h.

You are detained for the purposes of a search.

-

3)

Dignity and Respect

Evidence that the officer behaved in a respectful manner towards the citizen:

-

0 = officer showed disrespect; 1 = officer showed neither respect nor disrespect – ‘business-like’ behaviour; 2 = officer showed brief respect; 3 = officer showed intermittent respect; 4 = officer showed dominant respect.

-

4)

Trustworthy Motives

Evidence the officer showed care and concern – Yes/No.

Evidence the officer linked the need for the search to delivering GMP purpose of protecting society and helping to keep people safe – Yes/No.

The study also assessed some additional factors about the encounter.

-

Outcomes

Arrest – Yes/No.

No Further Action – Yes/No.

Unknown.

-

Gender

Citizen – Male/Female.

Officer – Male/Female.

Numbers of officers.

Numbers of Citizens.

-

Ending

Did the encounter appear to end positively – Yes/No.

The videos also contained audio recording of the encounter. This allowed for the coding of the dialogue between the officer and citizen for the dimensions of procedural justice. In coding, the study was concerned with whether there was behaviour or dialogue or both that indicated a particular procedural justice dimension, or constituent element of it. Frequency of occurrence was not recorded. When an officer activates their BWV camera to record there is a 30-second buffer, this enables the recording to capture 30 s before activation, but crucially without sound. The officer can manually override this and start the audio recording earlier; however, this does not occur as a matter of routine in the videos observed for this study. This presents a limitation to this study. There may be some dialogue that is not captured which may actually cover some of the dimensions of procedural justice that cannot be determined in this study.

Similarly, the sequencing of events was not recorded as the focus was on whether the dimensions were evident or not. The videos also enabled the day and time and the gender of the actors to be recorded. In essence, the main technique used is described by Robson (2002) as event coding.

Where there was a binary outcome of yes or no, it was given a measure of 1 or 0 respectively. Some aspects coded for, as detailed earlier, were coded on a scale allowing for a richer understanding of the depth and quality of a given element. The scale range for each of the four elements of procedural justice were:

-

Citizen Participation/Voice – 0-7

-

Explanation/Neutrality – 0-8

-

Dignity and Respect – 0-4

-

Trustworthy Motives – 0-4

The codified data was imported into the IBM Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) for statistical analysis, thereby enabling the descriptive statistical analysis contained within this thesis.Footnote 1 Correlations were calculated using Pearson’s r. The correlations between each of the elements were analysed against the overall procedural justice score (PJ score) and correlations between each of the four dimensions. Further analysis was conducted using the Mann-Whitney U tests to compare mean differences between each of the separate elements and the PJ score against time, outcome and gender.

There were 152 citizens involved in the 100 cases analysed. In 56 cases, there was only one citizen. It is possible for a citizen to be stopped and searched on more than one occasion. There was no one visually identified within the 100 cases by the coder that fit this category. It is important to note that identities of citizens were not ascertained or recorded as part of this study. In the corresponding stop-and-search encounters, there were 228 police officers. Similarly, the study was not designed to identify individual officers. However, from the review of the videos, it is evident that some officers appear in more than one encounter. The frequency of officer appearance could not be accurately assessed as the data storage system (Evidence.com) does not allow for all officers captured on the video to be identified. Only the officer uploading the video is captured on the system automatically. This is the officer who has recorded the encounter as they have to upload the video through the docking unit at the police station. Similarly, the identity of the officer could not be ascertained through the Duty Management System.

Findings

Officer to Citizen Ratio

The average ratio of officers to citizens is in the 100 cases was three officers to two citizens. Fully 95% of encounters involve not more than 2 citizens, with 56% involving only one citizen and 39% involving two. For officers, 72% of cases reviewed involved two officers, and a single-officer encounter comprised 12% of cases. In some cases, the number of officers involved increased during the encounter, with more officers arriving, either by request or by self-deployment after hearing radio communications. Where this occurred the officer number was recorded as the maximum number involved during the stop and search.

Gender Distributions

As Table 1 below shows, in 62% of encounters, the officers were male only, in 3%, they were female only and in 35%, they were mixed both male and female. There was a higher portion of male-only citizen encounters at 84%, with 5% female only and 11% mixed both male and female (Table 1).

A series of Mann-Whitney tests indicated no statistically significant difference between gender and each of the four elements of procedural justice elements. The test did indicate, to a statistically significant level, that in cases where a female citizen was present individually, in an all-female group or in a mixed female and male group (M = 64.75), there was a greater indication of overall procedural justice when compared to male-only citizen encounters (M = 47.79), U = 444.0, p < 0.05. There were no statistically significant differences across different combinations in the gender of officers in the overall levels of observed procedural justice recorded for citizens.

Daytime vs. Night Encounters

The time of the stop-and-search encounter was recorded as the time the video recording began. This was then further coded into two categories: day or night. There was a near equal split between stop and search encounters undertaken in the day and those undertaken at night, at 56% and 44% respectively.

A Mann-Whitney test indicated that the quality and depth of explanation and sense of neutrality shown to citizens in an encounter is significantly greater at night (M = 57.83) than in the day (M = 44.74), U = 909.5, p < 0.05). Overall procedural justice value is also greater at night (M = 60.02) than in the day (M = 43.02), U = 813, p < 0.05.

Participation/Voice

As described earlier, voice is an important element for the citizen to feel able to have some form of participation or influence in the officer’s decision-making process (Folger 1977). This study coded for five constituent elements which combined provided an overall voice score: officer actively sought the citizen’s viewpoint, citizen provided their viewpoint, citizen was given space to speak, citizen was offered an opportunity to ask questions, and officer listened to the citizen.

Voice was coded on a scale ranging from 0 to 7, where 0 indicated no voice at all and 7 indicated all elements of voice present. Eighty-nine (89) of the 100 encounters were rated 6 or higher. The mean value for voice is 6.56. This provides strong evidence that citizens in the videos studied were able to express their views and officers listened attentively to the views expressed. There are a few extreme examples where this was not the case. The lowest voice value was 2 and that was in a single case. This case also had the lowest overall PJ score at 5.

There is a statistically significant, strong correlation between the dimension of voice and the overall PJ score in each case (r = 0.699, p < 0.001). This is consistent with Jonathan-Zamir et al.’s (2015) findings, which suggest that voice is a substantial contributor to the overall level of procedural justice.

Seeking a citizen’s viewpoint naturally lends itself to the use of questions to elicit the citizen’s viewpoint. When done effectively, in a calm and polite manner, it can encourage the citizen to volunteer information and reduce the risk of conflict. One video shows a football fan being searched during a match as it is suspected he was in possession of drugs:

Officer: ‘Have you got anything on you that you shouldn’t have mate?’

Citizen: ‘Yeah I’ve got a little bag here.’ He then hands over a small bag containing white powder to the officer.

Officer: ‘What is it mate?’

Citizen: ‘Cocaine.’

Throughout the officer engaged the citizen in conversation, predominantly through asking questions and also by explaining the process and what to expect next. The citizen was arrested. A slight variation on this approach can also result in a positive outcome whilst minimising conflict. In one of the videos, an officer takes a slightly more authoritative approach, which could be viewed as potentially violating the principles of procedural justice. The officer approaches a parked car and tells the driver and occupants he can smell cannabis:

Officer: ‘So lads if you’ve got any shit on ya I can deal with it without arresting any of you.’

Citizen: ‘We had a little spliff.’

Officer: ‘Lads please don’t mess me around, I’ve been a cop for a very long time I know cannabis and what it smells like … if we have to start taking you out and searching you all … whoever has got a bit hand it over.’

Citizen: ‘We got a little ten bag.’ The passenger then hands over a small bag of cannabis.

Whilst seeking the citizen’s views, the officer seems to be directing the conversation towards a cannabis street warning outcome. This would entail less time and work for the officer. The approach taken in this case may be a result of the officer’s experience knowing that offering some options and room to manoeuvre may engender greater citizen compliance.

In both cases, the officers have actively sought the citizen’s view. This was done with the apparent purpose of locating drugs in a quick and safe manner through gaining cooperation. Where the citizen’s view is not actively sought, conflict could arise. In another video, a man is seen in his parked car. The police officers tell him witnesses indicate he was seen loading boxes and circumstances that lead them to suspect he is in possession of drugs. The first few minutes are dominated by the officers telling the citizen about the circumstances and that he is to be searched. The citizen keeps asking questions, which they answer, but do not actively seek his view. The interaction turns into a verbal conflict and disagreement.

Officer: ‘Keep your hands where I can see them please, put your phone on the seat.’

Citizen: whilst still using his phone ‘Give me a sec.’

Officer: in a raised voice ‘Listen … if I have to put you in handcuffs I will do’.

The interaction is peppered with an officer giving the citizen instructions which he questions or refuses to accept. But there is no evidence in the video of the citizen’s view being sought. The circumstances in which an officer seeks a citizen’s views can affect the quality of response or compliance. One of the videos records an officer restraining a youth by pushing him against the bonnet of a police vehicle and then to the floor placing him in handcuffs:

Citizen: ‘Wow what have I done mate?’

Officer: ‘Don’t fuck about. Do you think it’s good to make hoax calls?’

The citizen appears in pain and continually complaining about his wrist. Another person runs over and challenges the officers asking ‘what are you doing to him?’ The officers say they suspect the youth has a knife on him, then tell him to go away. The other person eventually leaves stating he will make a complaint about the police.

Officer: ‘What you running away for?’

Citizen: ‘Wow I’m running from them mate, for fucks sake bro.’

In circumstances where it is suspected a citizen is in possession of a knife, the officer is more likely to take a firm, directive approach with the use of force. In such cases seeking the citizen’s view can come later in the interaction. This is in contrast to the earlier videos discussed, where the officers sought the views of the citizen at the start of the encounter. However, where force is used it could be argued that citizen consent has been withdrawn and so ‘authority itself has failed’ (Bottoms and Tankebe 2012 p.134).

There are times where the citizen readily offers a view without being asked, which could be perceived as the citizen probing for an opportunity to be heard. For example, in one of the videos, the citizen is detained and handcuffed having been suspected of being in possession of a knife. The officers give clear and forceful commands. While they seek further information, the citizen is continually talking.

Radio Operator: ‘I know you said he is covered in mud, any blood on him?’

Citizen: ‘I’m just wet from rain sir. I’m not covered in blood sir I promise you sir. Would you like me to get on my knees sir?’

He continues talking while the officer briefs a colleague.

Officer: ‘Shut up … I’m not going to tell you again shut your mouth.’

After about 10 min, a more productive conversation evolves with the officer actively seeking the citizen’s view and listening to him whilst he responds.

Voice of the citizen can be captured through nonverbal communication in response to a string of questions by the officer. In one instance, an officer stopped a car with the driver standing by the road:

Officer: ‘Anything I need to know about you or the vehicle?’

Citizen: Shake of the head.

Officer: ‘Ever been arrested before?’

Citizen: Shake of the head.

Officer: ‘Any drugs in the vehicle?

Citizen: Shake of the head.

Officer: ‘Any drugs on you?’

Citizen: Shake of the head.

The officer then explains the grounds for the search. The citizen appears tired. The searching officer’s questioning style changes from a series of quick short sentences, with quick responses, to more engaging questions about lifestyle which appear aimed at building a rapport. Throughout the questioning, the officer allows space and time for the citizen to have a voice. This aspect of space and time is often in a state of flux throughout the interactions. It could be seen that this is linked to whether the citizen feels the ‘power-holder is justified in claiming the right to hold power over the citizen’ (Bottoms and Tankebe 2012 p.124). However, this feeling is not a constant and can be influenced by the level of procedural justice experienced. One of the videos records two men being searched; one is already handcuffed when the recording starts:

Citizen: Speaking to the second man ‘I’ve been nicked before, they’re arseholes mate.’ Speaking to restraining officer ‘Fucking no need for this lad, you don’t need to put me in cuffs.’

Officer: ‘You act like a prick we’ll treat you like a prick.’

The officer continues to hold the citizen and pushes him against a police car. The citizen becomes agitated, clearly upset at how he has been treated. To this point, no attempt has been made by any officer present to provide the citizen with the space and time to offer his viewpoint or to ask questions. The citizen disputes the officer’s authority to use a Taser which is a clear indication he is questioning the officer’s legitimacy and in turn his obligation to follow any instruction given.

Citizen: Talking to searching officer ‘He’s just stormed up … and had a Taser in his hand.’

Searching Officer: Interrupting the citizen ‘Listen, just listen, listen.’

Citizen: To restraining officer ‘You’re not allowed to get out of a car with a Taser in your hand, no you’re not, no you’re not, no you’re fucking not.’

Restraining Officer: ‘Do you want to tell us how to do our jobs for us?’

Citizen: ‘And you as well mate, you’re getting a bit old for it.’

Officer: ‘I’m not your mate.’

Explanation/Neutrality

The dimension of explanation in procedural justice theory is closely linked to the concept of neutrality. For officers ‘to be neutral’ they ‘need to make their decisions using objective legitimate criteria’ (Jonathan-Zamir et al. 2015 p.854). Police officers in England and Wales are required, among other things, to provide a detailed explanation about why an individual is about to be stopped and searched. Doing so brings transparency to the officer’s decision-making process.

The scale used to code explanation/neutrality ranged from 0 to 8, where 0 indicated the absence of the aspects explanation/neutrality and 8 indicated they were all present. There is a broader spread of explanation values when compared to those of voice with 70% of cases in the range 5 to 7. There are only single cases in the extreme values of 0 and 8. The mean explanation/neutrality value is 5.22. We found a strong correlation between explanation/neutrality and the overall PJ score of the encounters (r = at 0.77, p < 0.001).

Explanations of grounds given for the stop and search were coded into one of three possible reasons: stolen/prohibited items, weapons or drugs. There were 36, 16 and 43 searches in each category respectively, leaving five encounters in which no grounds were given. Where a search was undertaken for cannabis the grounds were based on the officer being able to smell the drug. ‘The Authorised Professional Practice stated that the smell of what the officer believes to be cannabis on its own will not normally justify … the search of a person who smells of cannabis’ (Quinton et al. 2016 p.6). But imposed searches are not necessary if consent is given. In one incident, for example, an officer spoke with two Asian men stood next to a sports car at night in the city centre, following reports of them revving the engine loudly:

Officer: ‘Who’s the one been smoking cannabis?’

Citizen 1: ‘Not us.’

Officer: ‘Gent’s I don’t need to do searches do I? I can smell it.’

Citizen 1: ‘You can search us.’

Some further conversation took place during which the officer complimented them for possessing a nice car. The officer continues to build a rapport with the men culminating in the officer asking:

Officer: ‘Have you been smoking it?’

Citizen 2: ‘I have, I have.’

The officer provides the grounds for the search and legal power covering other aspects of the principles governing stop and search in England and Wales. The only exception was the requirement to explain to the citizen that he or she was being detained for the purpose of a search. His explanation is clear and demonstrates his decision-making leading to the search. This could help to provide the citizens with a sense the officer is behaving in a neutral manner.

Officer: ‘Have you got any cannabis on you.’

Citizen 2: ‘I’ve got a joint.’

Officer: ‘Okay, let’s start being honest with each other.’

The demeanour of the citizens is complaint and clam, as is the officer. However, this last statement by the officer indicates he believes they have been dishonest to this point. Nevertheless, the citizens continue to engage and comply with all requests, potentially indicating their acceptance of the search and the manner in which it was done.

Officer: ‘We started off on the wrong foot, but you’ve been honest with me now.’

Officer: ‘What I’m going to do mate, is I’m going to search you under s.23 of the Misuse of Drugs Act … have you got anything else on you? Coz if I do find anything I’m going to lock you up so 100% honesty … I heard the car come over I could smell cannabis, I asked you if you had smoked cannabis, you said you had smoked a cannabis joint, I knew for a fact you hadn’t. You are entitled to a copy of the search record which I will do for you now.’

By saying ‘I knew for a fact you hadn’t’ the officer is potentially weakening the strength of neutrality as this statement implies an assumption on the part of the officer. This could lead the citizen to question how has the officer reached such an assumption? There is nothing observable through the video which would provide a definitive answer to the question. It could be based on a range of factors; unconscious bias, prejudice, strength of cannabis smell, previous experience or some other unknown factor.

Throughout, the officer explained the process in detail, answered all their questions and used humour, with all three laughing at times. The citizens appeared to leave in a positive and friendly way. In contrast, when a detailed explanation is not provided, this can hamper the quality and depth of conversation. One of the videos shows an officer speaking to a passenger in a car at night. Four other occupants have made off from the car before the officer could reach it:

Officer: ‘Why have your mates legged it?’

Citizen: ‘I don’t know. Can I go?’

Officer: ‘No you can’t you can stay here until you tell me what’s going on.’

There has been no explanation given by the officer as to why he is telling the citizen he cannot leave and is effectively being detained. If the officer was to explain grounds and object of search, show warrant card upon request, identify himself and the station to which he is attached, and the legal power used, then the citizen would be legally detained. The citizen could also then have assessed whether he felt the explanation provided a sense of neutrality of decision-making.

Officer: ‘It stinks of cannabis is that why they’ve legged it?’

Citizen: ‘Search me pal I’ve got nothing on me.’

Officer: To radio operator ‘Cannabis reeks in this place so he’s going to get searched.’

The officer takes the man out of the car, handcuffs him and places him in a police vehicle, all without any explanation. It is reasonable to assume the man knows at this point he is likely to be searched. However, it is also reasonable to assume he may feel his treatment has been procedurally unjust.

Officer: ‘Right at the moment you are being detained for the purposes of a search.’

Citizen; ‘Promise you there’s nothing on me, can you just search me coz I really need to be up for college in the morning?’

Officer: ‘You weren’t going anywhere when I drove up were you?’

Citizen’ ‘Coz I’ve got nothing to hide.’

The officer does not appear to be building any rapport or trust with the citizen and in fact, his words make it clear he does not believe him. Equally, the citizen appears to be resigned to being detained and not being believed. Overall the explanation given is weak leaving long periods of silence between the officer and citizen.

On occasion, a citizen can tip over into a highly agitated and angry state very quickly. Video 27 shows a rapid deterioration from compliance to violent resistance:

Officer: ‘It stinks of cannabis.’

Citizen: ‘Yeah so what. I’ve got a car key have I been driving it?’

Officer: ‘Don’t be awkward.’

Citizen: ‘Who you talking to I’m not no muppet … you can’t do nothing … don’t treat me like a fucking muppet mate.’

Officer: ‘Watch your language.’

Citizen: ‘Do you want me to go mad?’

The Officer then engages with Citizen 2 during which he grabs hold of that citizen, to which Citizen 2 reacted angrily.

Citizen 2: ‘What are you detaining me?’

Officer: ‘I’m detaining you for a search.’

The entire encounter deteriorated rapidly with Citizen 1 grabbing a metal bar from a nearby skip threatening to damage the officer’s van. The officer took out his C.S. spray and threatened to use it against Citizen 2 if he did not comply. Whilst the explanation given was weak, it could be argued that the officer had little time to do so before the incident rapidly escalated into a threatening and violent one. This could be due to the citizen’s predisposition of dislike for the police, the demeanour of the officer or other unknown factors.

Even in an encounter where the citizen is agitated it is still possible to provide a detailed explanation of what police are doing and why. A man was detained and placed in handcuffs after a report of a disturbance in a supermarket and allegation that he was in possession of a knife:

Officer: ‘It’s been alleged that you’ve got a knife on your person. You’re going to be searched mate under section 1 of PACE.’ Officer then provides his name and the police station to which he is attached. ‘You are entitled to a copy of this stop search form.’

Citizen: ‘Can I have a copy please.’

Officer: ‘The object of the search is to find any articles that may be prohibited … have you got anything on you that may cause injury to me or you?’

Citizen: ‘No.’

Officer: “You matched the description.’

The officer provided a clear explanation of why the citizen was to be searched; this made his decision-making process clear to the citizen. In return, the citizen was calm, compliant and polite despite having been chased and detained by the officer. The officer places no personal value judgements in the explanation, simply recounting the information he has been given and how this has led him to believe the search is necessary. No knife was found and so no further action was taken. Had the citizen actually been in possession of a knife then he may have behaved differently and been more evasive. However, this is not a certainty. As in Video 13, a citizen may volunteer to surrender items that are the focus of the search.

Dignity and Respect

This dimension is coded on the basis of observed ‘police respectfulness, the quality of interpersonal treatment’, treating a citizen politely, showing concern for a citizen’s rights and ultimately treating the citizen with respect and dignity (see Tyler and Wakslak 2004 p.257) In coding for dignity and respect the study has observed the extent to which the officer displays and behaves in a respectful manner. This has been recorded on an incremental scale from 0, being disrespectful, to 4, showing dominant respect. The mean value for dignity and respect was 3.54.

Over three quarters of the encounters recorded dominant respect (n = 76) with a value of 4. In 11 cases the officers showed business-like behaviour of brief respect. There was only one encounter in which the officer displayed disrespect. There was a strong and significant correlation between dignity and respect and overall procedural justice score (r = .71, p < 0.001).

There are occasions where the words and behaviour of the officer do not match. This can be identified through voice intonation and non-verbal communication. In one of the videos, a black man is stopped in the city centre by a white police officer following a report by doormen of a nightclub that he had been dealing drugs:

Officer: ‘Report from door staff that you might be involved in drug dealing.’

Citizen: ‘Not true.’

Officer: ‘You’ve dumped it all up there have you?’

Citizen: ‘You can search there bro, I never done nothing.’

Officer ‘Nah I’m alright.’

In making this statement, the officer’s tone could be interpreted as he does not believe or trust the citizen. Later in the encounter, another officer arrives briefly and the first officer can be heard whispering to the second that he believes the citizen has thrown his drugs away before he was stopped. The officer continues by asking the citizen a series of questions.

Citizen: ‘Do you have to be asking me these questions?’

Officer: ‘Yeah I’ve never met you before, of course I’m asking you the questions.’

Citizen: ‘Do I have to respond to them?’

At this point, the officer does not answer the citizen’s question directly thereby displaying a lack of respect towards him. This appears to frustrate the citizen; nevertheless, he remains compliant. As discussed earlier there is no legal requirement for the citizen to provide any details, unless he is to be reported for an offence in which case he would have to provide his name and address. It is likely the officer will, or certainly should, know this and so without answering the citizen’s questions feels able to create a presumption of necessity for the citizen that he must answer the questions. If this is the case then the officer is adopting a technique to circumnavigate the strict rules, procedures and guidance surrounding the use of stop and search (HMICFRS 2015).

Citizen: ‘I’m a calm person … I’ve nothing to do with drug dealing … I’m going home … am I being detained?’

Again the officer ignores the question asked and continues in conversation explaining why he has stopped the citizen and why he is asking so many questions. In response to the officer’s behaviour the citizen is potentially feeling he is not being shown the level of respect he deserves.

Citizen: ‘Am I detained right now?’

Officer: ‘Erm, I can detain you yeah, for the purpose of a drugs search.’

The officer continues to explain that he may conduct a search. However, he tells the citizen he is detaining him to obtain his details, for which there is no legal basis in the given circumstances. The legal power is to detain for the purpose of a stop and search (Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 2015), which the officer does not make clear.

The citizen asks a question which potentially shows his thinking

Citizen: ‘So you choose to stop me out of all people?’

Here this question could be interpreted as having several meanings. It is possible it has built on a sense of being treated without dominant respect, of being treated unfairly and differently due to race. There is nothing captured on the video which could confirm such a perception.

In some encounters, officers display low levels of respect yet may perceive they are being professional as their behaviour and language is very business-like. From the citizen’s perspective, such behaviour and approach may feel cold, distant and lacking any empathy. In one of the videos, a car is parked in a carpark of a hotel during the day with two male occupants when a police car, with two male officers, pulled up in front of it. The approach of the two officers differs:

Officer 2: ‘What you up to lads?’

The officer speaks in a calm, engaging and respectful tone to citizen 1 who steps out of the car from the driver’s seat.

Officer 1: ‘Turn your engine off.’

In contrast, this officer has an authoritarian tone towards citizen 1. Officer 1 walks to the passenger side of the car and engages with the front seat passenger.

Officer 2: ‘Just come out to me mate.’

Officer 1 (Speaking to citizen 2, who is in the car): ‘Stay in the car.’

Then turning to citizen 1, Officer 1: ‘Dude move back here.’

While commanding the behaviour of citizen 1 the officer points at him with one finger and then points to the side of the car where the officer expects citizen 1 to stand. The citizen duly complies. Officer 1’s instructions are short and authoritative. His words and behaviour show little respect. Whilst still pointing at citizen 1 with his finger and arm outstretched:

Officer 1: ‘Move back here. You’re going to be searched and whilst you’re searched you’re going to be handcuffed.’

Officer 2 then handcuffed citizen 1.

Officer 1: to citizen 2 ‘You are currently on camera … you’ve been handcuffed coz I’ve seen you fiddling about with stuff … so for my safety and yours you have been handcuffed for the purposes of a search, your car stinks of weed.’

Citizen 2: ‘Yeah we’ve been smoking weed.’

To this juncture, officer 1 has not asked either citizen any questions but merely given instructions or made statements. Neither citizen has in any way been confrontational, evasive or disrespectful. This officer’s behaviour, tone and body language has shown disrespect or at best a business-like approach. This approach is further displayed when citizen 2 asks for the officer to remove citizen 2’s sunglasses from citizen 2’s face for him.

Officer 1: ‘I will take your glasses off for you at your request sir, thank you very much.’

While seemingly using polite language the officer’s body language and demeanour suggest a lack of genuine respect. This differs from the continued approach taken by officer 2 who is respectful in both behaviour and language.

Officer 2: Whispered softly ‘Keep facing the car mate, nice one.’

As officer 1 searches the car citizen 2 becomes more frustrated. The lack of respect may have helped to contribute to the frustration. At 08 min and 42 s after the start of the encounter, whilst still handcuffed citizen 2 said:

Citizen 2 ‘This is ridiculous I swear to God.’

There are moments during the encounter where officer 1 seems to show a lack of respect for officer 2. This is seen when officer 1 directs citizen 1, who is being dealt with by officer 2, thereby potentially undermining and disrespecting his authority. Officer 1 also tells citizen 1 he is going to be handcuffed, which removes officer 2’s discretion and obliges him to handcuff citizen 1. This could be interpreted as officer 1 lacking confidence and respect in officer 2’s decision-making abilities or in his judgements.

The mere act of being genuinely respectful towards the citizen does not always prevent confrontation and the need to use force. In one instance, a 14-year old boy is stopped on the street following a report that he may have a knife. Some of the boy’s friends are nearby but not stopped or searched; however, they do wait:

Citizen: ‘At the age of 14 I don’t want youse to search me.’

Officer: ‘I understand that but because we’ve got intelligence that a male matching your description has been seen carrying a knife I’m going to search under section 1 of … ’

Citizen: ‘But at the age of 14 I don’t feel comfortable with you searching me without my mum being here … you’re not going to search me.’

The officer grabs the citizen’s arm and his behaviour changes instantly. He becomes extremely angry and resists violently continually screaming loudly:

Citizen: ‘Get off me, get off me, nah seriously get off me, I’m 14, I’m not going to let you search me, get off me, just get off me … ’

Officer: In a relaxed soft tone. ‘Calm down, calm yourself down.’

The citizen’s friends also try to calm him and ask that he complies.

Officer: Using the citizen’s name. ‘Yeah good lad just calm down.’

The officer has been polite and respectful throughout the encounter. Eventually, the citizen does calm down and the search is completed.

Citizen: ‘Obviously I’m sorry for being like that … I’m sorry.’

Officer: ‘You seem sound you just went up there all of a sudden.’

Trustworthy Motives

In PJ theory, a citizen will infer the motivations behind an officer’s actions and decisions from their words and behaviours. There are four components of trustworthy motives. First is how far an officer displayed care and concern for the citizen (Jonathan-Zamir et al. 2015@@). Greater Manchester Police’s (GMP) mission is ‘protecting society and helping to keep people safe’. If an officer’s statements link the search to this GMP purpose, it would provide a level of consistency and clarity as to the officer’s motivation. In principle, such statements can strengthen a citizen’s belief that the officer had trustworthy motives about protecting society. Second, trustworthy motives about protecting the citizens encountered. Correctability is the third component. It means the ability of citizens to ‘complain about unfairness by a law enforcer to some agency or organization’ (Makki and Braithwaite 1996 p.84). It is the ‘existence of opportunities to correct unfair or inaccurate decisions’ (Tyler 1988 p. 105). The procedure for this is set out in the expected practice when undertaking a stop and search. The officer is expected to explain the complaints procedure and signpost them to where they can access forms to trigger a formal complaint. Finally, if a citizen is compliant through the encounter it would indicate a trust in the motivations of the officer. This study reviewed and coded the videos for all four aspects.

The range of values for trustworthy motives was from 0 to 4, where 0 would indicate none of the aspects coded for were present and 4 would indicate they were all present. Given that in none of the 100 encounters coded did any of the officers link the necessity for the stop and search to the GMP purpose, there were no encounters recoded with the maximum value of 4. The mean value was 1.87. Over two thirds—68%—of searches had a value of 2, 18% had a value of 1 and 3% had a value of 0. The highest value recorded was 3 in 11% of encounters. The correlation between trustworthy motives and overall PJ score is moderate at 0.54, p < 0.001.

Care and concern are important for a citizen to perceive the officer as having trustworthy motives. This is even more so when dealing with vulnerable people. One of the recordings starts with an officer talking to a man, in company with his friend, who had money stolen from him whilst he was begging outside a supermarket. The man was an alcoholic who had previously self-harmed and attempted suicide. A paramedic was present and they were waiting for an ambulance as he had suffered from an epileptic fit.

Officer: ‘Do you want me to speak separately from this guy or are you okay?’

Citizen: ‘He’s my mate.’

Officer: ‘This paramedic tells me you said you are going to harm yourself. How do you feel at the moment?...Do you want to hurt yourself now?’

Citizen: ‘I will hurt myself.’

The officer’s tone and demeanour are patient and displays genuine care and concern. He encourages the citizen to go to the ambulance and explains about other support he will connect the citizen with. The ambulance crew refuses to allow his friend to travel with him. The citizen threatens to cut himself if his friend is not allowed to travel with him. The officer talk separately to the paramedic.

Officer: ‘Is it worth you taking one of your colleagues then his mate can jump in with him?...I’m just thinking what’s best in the situation that’s all.’

This further demonstrates the officer’s intentions and makes clear that the welfare of the citizen is his paramount consideration. A video shows the searching officer displayed great care and compassion throughout the search being very careful when searching the citizen’s handbag and removing items. The partner of the citizen who had been searched was under arrest, whereas the citizen was free to go. At the conclusion of the search:

Citizen: ‘Am I allowed to speak to him now?’

Officer: ‘No, let me just finish this, he’s under arrest.’

Citizen ‘Could you tell him I’m going to go home.’

Officer: ‘Yeah yeah we’ll pass that on to him.’

When considering correctability, there are encounters in which officers seemed open and genuine in providing details about the complaint procedure. The officer in a video mentioned earlier under explanation/neutrality went into great detail about how the citizen could make a complaint and seek redress.

Officer: ‘If you’ve got any issues with the way you’ve been treated … you can contact www.police.uk to make a complaint about the conduct of myself (officer provided his rank name and collar number) if you don’t want to go through GMP you can go through the Police and Crime Commissioner, he has an internet site, he is also on Facebook and Twitter.’

Citizen: ‘No problem. Nice one.’

The stop-search form can be used as a means of communicating the procedure to complain. A video captures the search of three youths; one was found in possession of a ball-bearing gun.

Officer: ‘You can get a copy of the search record if you want. It says you have a right to complain if you feel you were unfairly searched or if we treated you badly.

Citizen: ‘No it’s alright.’

Officer: ‘Well some people do don’t they.’

There were also some cases where even though the complaints procedure was mentioned or explained, it was as a response to the threat of a complaint by a citizen. This might be a tactic to prevent complaints. By being upfront it may make the citizen question the efficacy of making a complaint. In the video discussed under voice, the citizen is suspected of being in possession of a knife. A member of the public sees the police detain a boy and intervenes. The officers tells him to go away and not interfere. The member of the public asks for the officer’s collar number as he would be making a complaint, the officer responds:

Officer: ‘Happy days you can do what you like pal.’

The member of the public then walks away.

Citizen: ‘I’m telling PC (provides name of officer).’

Officer: ‘Good you can tell my Inspector for all I care pal.’

The officer then completed a search record and handed it to the citizen.

Officer: ‘If you’re not happy with the grounds you’ve been searched there is information on the back where you can contact the Police and Crime Commissioner and tell him why. There is an email address there.’

At face value, the officer is complying with the requirements of the stop-and-search procedure. However, given the fact that force was used by two police officers taking a 14-year-old boy down to the floor and placing him in handcuffs, it could be that the officers are more concerned about protecting themselves from any allegations of excessive use of force. This concern may have been heighted as an independent member of the public witnessed the incident and said he would be making a complaint. The justification given for the use of force was that they suspected he was in possession of a knife and did not comply with early instructions. The officer made this last factor clear:

Officer: ‘I’ve got a family to go home to. I’ve been told someone matching your description has a knife. I’m not taking any chances.’

Correlations Between Each Dimension of Procedural Justice

There are statistically significant correlations between each of the four elements of procedural justice and the overall PJ index in each case. The correlations are strong between overall PJ and voice, as well as between overall PJ and dignity/respect (0.76). The correlation is moderate between trustworthy motives and overall PJ. (0.426). The correlation between overall PJ and explanation is weak (0.204). A similar pattern is repeated when comparing each of the other elements. This is in slight contrast to Jonathan-Zamir et al’s work where correlations between the sub-indices, whilst statistically significant, were all much weaker, ranging from 0.10 to 0.30.

The overall procedural justice score is obtained by simply adding the value of each of the four elements together. The frequency distribution of the overall procedural justice score is shown in Fig. 1 below.

Conclusion

The evidence from this study demonstrates the capacity of body-worn video records to identify with great precision the specific strengths and weaknesses of each stop-and-search encounter between police officers and citizens. Rather than a global assessment of police practice as simply “good” or “bad,” the coding of BWV records of stop-and-search encounters allows training to target both specific dimensions of PJ as well as specific officers.

In this sample of 100 cases, the coding of voice and citizen participation are very high and consistently so, with 96 cases recording 5 or above. This would suggest there is no requirement to focus effort on improving this aspect of PJ. Dignity and respect also scored highly on the index and had only 12 cases that scored 2 or below. Consequently, this aspect would not necessitate the focus of effort and allocation of precious training resources.

Explanation and neutrality had a broader spread across the values and a lower index score than the previous two dimensions. However, if a system was designed to identify the officers through ongoing tracking, then there could be remedial training or supervision targeted only at those officers who scored 5 or below.

Finally, there appears to be a need to focus most remedial attention on improving officers’ abilities to deliver a greater sense of trustworthy motives to citizens. In particular, there is a need to review student officer training. This review could ask how a greater focus might made to deliver a stronger sense of there being trustworthy motives in a stop-and-search encounters for citizens. If successful, such training could help to increase legitimacy. Such improvements will also help to strengthen community trust and confidence in policing.

Another policy implication of this research would allow for the building of an ongoing tracking measure for police legitimacy that could be used as a supervisory and human development tool for operational officers. It could be used to compare individuals, units, areas, and trends over time in objectively coded features of police behaviour towards citizens.

Utilising the same methodology for measuring procedural justice, future research could create a randomised control trial (RCT) to assess whether this targeted training (if delivered) made any measurable difference to the index value of each dimension. As described earlier, it is critical that policing improves its use of stop and search. To achieve, it must be open to this scientifically rigorous approach to help build the evidence base and improve the sense of legitimacy for the citizens. The dangers in continuing to get stop-and-search practices wrong for individual citizens, police officers and wider society are too great for us not to try.

Notes

The study has ensured it adhered to and operated within the framework of the Code of Ethics, a code of practice for the principles and standards of professional behaviour for the policing profession of England and Wales (College of Policing 2014).

References

Bottoms, A., & Tankebe, J. (2012). Beyond procedural justice: a dialogic approach to legitimacy in criminal justice. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, pp. 119–170.

Bowling, B., & Phillips, C. (2007). Disproportionate and discriminatory: reviewing the evidence on police stop and search. The Modern Law Review, 70(6), 936–961.

Brunson, R. K., & Miller, J. (2006). Gender, race, and urban policing: the experience of African American youths. Gender and Society, 20(4), 531–552.

College of Policing (2014). Code of ethics. In A code of practice for the principles and standards of professional behaviour for the policing profession of England and Wales.

College of Policing (2015). Fair effective stop and search. Retrieved on 25th January 2018 from: http://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=3&cad=rja.

Delsol, R., & Shiner, M. (2006). Regulating stop and search: a challenge for police and community relations in England and Wales. Crit Criminol, 14(3), 241–263.

External Relations and Performance Branch. 2018. Greater Manchester Police. In Stop and search performance report- 2017-18 Q2. Internal Document.

Folger, R. (1977). Distributive and procedural justice: combined impact of voice and improvement on experienced inequity. J Pers Soc Psychol, 35(2), 108.

HMICFRS (2016). Greater Manchester PEEL 2016: more about this area. Retrieved on 25th January 2018 from: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/peel-assessments/peel-2016/greater-manchester/more-about-this-area/.

HMICFRS, London (2013). Stop and search powers: are police using them effectively and fairly?.

HMICFRS, London (2015). Stop and search powers 2: are the police using them effectively and fairly?.

Jonathan-Zamir, T., Mastrofski, S. D., & Moyal, S. (2015). Measuring procedural justice in police-citizen encounters. Justice Quarterly, 32, 845–871.

Lewis, P., Newburn, T., Taylor, M., Mcgillivray, C., Greenhill, A., Frayman, H., & Proctor, R. (2011). Reading the riots: investigating England’s summer of disorder.

Manchester Population (2017). (Demographics, maps, graphs). Retrieved on 25th January 2018 from: http://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/manchester-population/.

Mazerolle, L., Bennett, S., Davis, J., Sargeant, E., & Manning, M. (2013). Legitimacy in policing: a systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 9(1).

Office for National Statistics (2011). Ethnicity and national identity in England and Wales 2011(Online) retrieved 25th January 2018. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/ethnicity/articles/ethnicityandnationalidentityinenglandandwales/2012-12-11.

Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (2015). Code A, H.M.S.O.

Quinton, P., McNeill, A., & Buckland, A.. (2016). Searching for cannabis are grounds for search associated with outcomes?. College of Policing.

Reiss, A. J. (1971). Systematic observation of natural social phenomena. Sociol Methodol, 3, 3–33.

Robson, C. (2002). Real world research (2nd ed.). Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Sahin, N.M. (2014). Legitimacy, procedural justice, and police-citizen encounters: a randomized controlled trial of the impact of procedural justice on citizen perceptions of the police during traffic stops in Turkey (Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University-Graduate School-Newark).

Sunshine, J., & Tyler, T. R. (2003). The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law & Society Review, 37(3).

Thibaut, J. W., & Walker, L. (1975). Procedural justice: a psychological analysis. L. Erlbaum Associates.

Tyler, T. R. (1988). What is procedural justice?: Criteria used by citizens to assess the fairness of legal procedures. Law and Society Review, pp. 103–135.

Tyler, T. R., & Huo, Y. (2002). Trust in the law: encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts through. Russell Sage Foundation.

Tyler, T. R., & Wakslak, C. J. (2004). Profiling and police legitimacy: procedural justice, attributions of motive, and acceptance of police authority. Criminology, 42(2), 253–282.

Webb, E. J., Campbell, D. T., Schwartz, R. D., & Sechrest, L. (1966). Unobtrusive measures: nonreactive research in the social sciences (Vol. 111). Chicago: Rand McNally.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the College of Policing and the Greater Manchester Police for their financial support of the research on which this article is based, which was led by the first author as a thesis submitted to the University of Cambridge in partial completion of the Master of Studies in Applied Criminology and Police Management at the Police Executive Programme, Institute of Criminology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nawaz, A., Tankebe, J. Tracking Procedural Justice in Stop and Search Encounters: Coding Evidence from Body-Worn Video Cameras. Camb J Evid Based Polic 2, 139–163 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41887-018-0029-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41887-018-0029-z