Abstract

The village of Varāy (Viyar) is located at the foot of Āq Dāgh Mountain in the southeast of Sultaniyya, Iran, and is known for its impressive rock-cut architecture called Dash Kasan. The history of Sultaniyya, which later became the Ilkhanid (Mongol rulers) capital, began with the issue of an order by Arghūn Khan (1258–1291 CE), to build a huge city enclosed by stone walls and fortifications. According to many in the field, Dash Kasan occupied a prominent place in the development of Arghūn’s architectural project; first as a stone quarry, and then as a Buddhist monastery. This building is unique in its architectural design and decoration. The site’s two large-scale dragon snakes carved out of cliffs, and the development of a vast open space by cutting the solid rock are the only examples of their kind in Iranian art and architecture. Although most of the debates on the identity of this site to date are centered on its religious function during the Mongol period, there is little architectural evidence to support this idea. Hence, the nature and the scope of earlier studies are not sufficient to substantiate the architectural discourse surrounding this monument. The aim of this paper is to study this enigmatic rock-cut complex to provide a more detailed description of the current remains. According to the results, the architectural layout of this building suggests it was originally designed as pre-Ilkhanid Mongolian ceremonial halls and reflects a Chinese, East Asian architectural influence that was evident and pervasive throughout the Mongol territories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

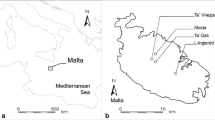

The city of SultaniyyaFootnote 1 was a key region in the Ilkhanid era (1256–1353 CE) due to its political, military, cultural, and economic contributions to the critical developments occurring in 13th-century Iran. According to historical literature, when Arghūn succeeded to the throne in 1284 CE, he ordered his officials to build a city in Qunqūr Ulāng, located to the southeast of Tabriz, the most important city in Ilkhanid-era Iran. However, because his life was short, he could not finish the project and his son, Öljaitü (1282–1316 CE), completed it and named it Sultaniyya (imperial) (Rashīd al-Dīn 1994: 1178; Ḥāfeẓ-e Abru 1992: 8). Rashīd al-Dīn’s statement highlights that the area was significant even before the rise of the Mongols and was the location of a city called Sharviyāz (Rashīd al-Dīn 1994: 1991), a name with Iranian etymological origin. Oriented in cardinal directions, Ḥamdallāh Mustaufī measured Sultaniyya’s outer wall which spanned nearly twelve thousand Qams (each Qam is approximately 45 cm)Footnote 2 (Mustaufī 1987: 59). Ḥāfeẓ-e Abru (died 1430 CE) describes the city wall as a stone-cut stronghold with a monumental entrance portal and sixteen towersFootnote 3 in which four horse riders could pass side by side at the top (Ḥāfeẓ-e Abru 1992: 8).Footnote 4 Surveys and excavations at Dash Kasan during the last decade of the twentieth century revealed that building materials for the construction of Sultaniyya and the neighboring monuments were sourced from Dash Kasan (Mirfattah 1997: 55).Footnote 5 In other words, Dash Kasan had the maximum potential for the exploitation of stone blocks to support such a large-scale project. It had the capacity to supply the stones for a number of years. More importantly, Dash Kasan could have been easily from Sultaniyya where construction activities were taking place (Fig. 1). The first discussions and analyses about the architectural origins of Dash Kasan emerged during the 1970s, attributing the site to Buddhist architecture, however, the physical nature of this site has not been fully understood. This study takes archaeological evidence and textual sources to review the earlier ideas about Dash Kasan without refuting them completely. Hence, it could be considered as an addition to the existing body of knowledge, to complement scholars’ earlier studies.

Current remains of Dash Kasan in Varāy, Sultaniyya. See from the northeast (Photo by Amin Moradi 2022)

2 Literature review

Sultaniyya and its surroundings have still not been fully archeologically explored and the result of the most recent excavations are not available in published form. The exploration of Dash Kasan was launched in 1973 by Iranian Archaeological teams, and from 1990 to 1992, excavations were only carried out for less than a month every year (Mirfattah 1997). Excavations conducted between 1994 and 1997 by Mirfattah resulted in the identification of the plan and the removal of construction debris from the area. However, no archaeological team has returned to the site since then. In 1974, Ganjavi introduced Dash Kasan as a pre-Achaemenid site that was repurposed as a monastery complex during the Mongol period. He also referred to the adjacent cemetery with Ilkhanid tombstones (Ganjavi 1974). In 1975, Scarcia visited the site when a significant portion of it was still under the debris. The identification of this site as a Buddhist monastery, first articulated by him in a brief article, is based upon its sophisticated figural representations of dragons. In contrast, Kleiss (1994) looks at this question more cautiously and never names the building as a Buddhist shrine or monastery. Scarcia noted that there is still an Iranian village called Viyar near Dash Kasan, a name which is believed to be associated with the Sanskrit Vihara (Buddhist monastery) (Scarcia 1975).Footnote 6 On the basis of this presumption, Azad (2010) and Blair (2014) point out that the name Viyar might itself be an indication that a Buddhist building (Vihara) once stood here. In her theoretical reconstruction, Blair suggested that the ground plan of this complex is symmetrical, but concluded that the builders then had the idea to cut the site according to a predetermined plan (Blair 2014) (Fig. 2). Fragments of stone capitals found on the site led Blair to conclude that a large part of the building was roofed (Blair 2014). Norallahy (2011) introduced the site as a temple dedicated to the Zoroastrian god Mithra, which was shaped during Öljaitü’s reign (1304–1316 CE). Çobanoglu (2021) attributes Dash Kasan to a Buddhist temple that was demolished after the wave of deliberate destruction of monasteries after Ghazan Khan’s (1271–1304 CE) epic conversion to Islam (1295 CE).

3 Methodology

The research method is structured to work on two levels. At the first level, it started from much broader aspects of architectural details and decorations by emphasizing the fieldwork to study the characteristics of Dash Kasan in detail. In an attempt to review the previous hypothesis while reviewing the existing architectural remains and documental modifications, an adaptation of laser scan results was brought into focus to create the ground plan of the site. The second level of the study is a typological comparison focused on the taxonomic classification of physical traits commonly found in East Asia. Combining these two levels will make it possible to propose an attribution regarding this building’s identity. Ultimately, this will allow new reflections on the history of Ilkhanid architecture and will have broader implications for the question of the function of Dash Kasan in the 13th and 14th centuries.

4 Description

As numerous local legends indicate, the mountain overhanging Dash Kasan is the site of a talisman in the form of an inaccessible cave with its relative source or sacred well connected through underground galleries with the very city of Zanjān (Scarcia 1975). Even today, shepherds periodically sacrifice their sheep there as part of a religious ritual. Dash Kasan is an irregularly shaped entity, measuring 110 m north-south and 40 m east-west at its maximum points. The orientation of the site is not aligned with a cardinal direction but is in fact seven degrees off due north.Footnote 7 The whole site lies on an elevation rising on three shallow levels along the slope of the hill and three stone-carved niches mark the borders of the site (Fig. 3). Approaching the complex from the north, one first sees a partly ruined hyperbolic niche marking the main axis of the site in the south. This vault is the spine which organizes the interior of the surviving sections of the complex, however, it is almost impossible to determine its exact dimensions. Moving along this axis, there are two further niches located on either side (east and west) of the main niche. While the eastern niche has a pointed arch, the western one presents a similar geometry to the main niche, albeit on a smaller scale. The large central niche measures 6.71 m across and 4.12 m in depth and is raised 2.38 m higher than the other niches. A gentle slope made by the quarrying process leads to the upper levels from where the central niche can be accessed. The platform on which these niches are located is more than eight meters above ground level. Since the central niche is assumed to be the common center of this monument, it naturally exhibits the finest decoration available. This includes elaborately carved decoration bands that cross its two sides and would have reached the top of the walls (that are no longer existent today). The initial Ilkhanid artistic aspects at this site can be identified as two dragon panels (ca. 535 × 173 cm) carved in a manner similar to those on the tiles excavated at Taḵt-e Solaymān (lit. Throne of Salomon), in west Azerbaijan, Iran.Footnote 8 Two sets of rectangular frames displaying muqarnas decoration flank the central niche, located at the outer edge of the south wall, and on either side of the eastern and western walls. As the remains of the lower part attest, it is obvious that the southern niche was decorated with repeating pairs of trefoil leaves, and two rectangular frames on either side of the dragon panels are decorated with more complex patterns consisting of vase-shaped forms with blossoms from which pairs of the leaves bloom. Judging by the composition of these panels and their actual dimension, it is very likely the same stonemasons who engraved them all, however, it is far more difficult to decipher whether or not the dragon panels were engraved by a second artist. Remains of a horizontal band are noticeable around the upper level of the western niche. This would suggest that an inscription or even decorative elements were supposed to be added to the well-polished cliff face (Fig. 4-left). While this preparation is absent in the eastern niche, the current condition of the southern niche does not allow for any speculation as to whether the same would have been true here. Evidence of square holes (ca. 20 × 20 cm) on top of the dragon frames is identifiable. These holes may have been used to anchor wooden scaffoldings to reach the upper levels or to work more closely on the details of decorations, and have similarly been found in contemporaneous buildings.

To date, several meters of deposits have been removed and the detail of the stone floor is clearly visible. Various intact polished stone surfaces suggest that the complex was meant to extend further north, but was never finished. A large number of iron and wooden wedges have been discovered during the excavation (Mirfattah 1997), which are attributed to use in the usual procedure for extracting blocks (by cutting a narrow channel around the right and left sides and the back). Flat wedges were thrust into slots, and carefully placed at joint lines. Iron wedges had to be hammered in, whereas wooden wedges, like those probably used at Dash Kasan, required less effort and would be put into place and soaked to split the block from the parent outcrop (Fig. 4). Nowadays, a similar method is practiced by villagers who extract ashlar in this traditional way in the nearby mine, some four kilometers to the west. While the length of the stones varies, the height is always the same (ca. 60 cm), thus facilitating their prefabrication off-site and allowing for speedy assembly on-site. The irregular method for removing stones from their natural bed in Dash Kasan indicates the possibility of multiple usages over time, even in later periods, and does not necessarily pertain to a Mongol phase.Footnote 9 Furthermore, some of the present-day villages in Northwest Iran bear the exact name “Dash Kasan”. It could be theorised that Dash Kasan is a term specific to no particular locality, but it simply used to denote a stone quarry. We then, therefore, have no clue about its ancient and original appellation.Footnote 10 When we look at the abundance of stone blocks scattered around the site with similar dimensions to those from the Sultaniyya citadel’s ashlar masonry, we cannot reject the idea that the site was also a quarry to provide materials for this impressive project and there is still a road leading from Dash Kasan to Sultaniyya that seems likely to have initially been prepared for transporting stones. Quarry-cut stones that were abandoned at some points along this road are visible even today (Norallahy 2011).

Little can be said about the general appearance of the main niche, but without further evidence, it would seem that a great deal of its top had fallen off (Fig. 5). This niche is part of the monolithic mass. It seems that the stone vault fell and fragmented as a result of erosion and deterioration. Even though this process could also be attributed to human interventions, there is no sign of an iron wedge on the wall profile intended to destroy it, so it is highly possible that this detachment occurred due to rapid wetting or from the force exerted by raindrops and runoff: the pressure of entrapped frozen water or the sheer force resulting from anisotropic swelling produce (micro-) fissures which weaken the aggregates. The upper parts of the eastern and southern niches are detached where this process has occurred. Severe rainstorms, which are common in the region, combined with the steep slope of the southern hill that leads to the site might cause this geologic erosion. In quarrying operations, considerable manpower is required and water is an important necessity for the workforce. It must be available in sufficient quantity near the quarry site. However, it is difficult to determine whether or not the fissure in the middle of the central niche is a natural fountainhead flowing to square ponds or just incalculable damage that accelerated the degradation process.

Remains of the western niche and evidence of quarrying operation in Dash Kasan (Photo by Amin Moradi 2022)

Remains of the southern niche in Dash Kasan (Photo by Amin Moradi 2022)

Almost contemporary with the remains in question, another interesting heretofore unknown rock-cut monument is located some 200 m behind the existing hill on the main axis of the site in the south direction (Moradi 2022). These remains have never been the subject of archaeological studies. Despite their ruined condition, evidence of cubic stone blocks carved using the same technique as well as several sherds attest to its probable connection to the current remains (Fig. 6). Thermoluminescence results from three sherds collected during a short period of the author’s archaeological investigation in 2020 demonstrated that this site’s historical identity does not differ significantly from Dash Kasan’s. The results (691 ± 22, 733 ± 25, 740 ± 20)Footnote 11 suggest that this site was built during the Ilkhanid period (1256–1353 CE) which overlapped with the construction date of the site at the heart of this analysis (Ibid). It should be mentioned that due to the steep slope of the ground and the impossibility of transferring stone blocks as a result, this second place could not have been used as a stone mine. However, it would be logical to conclude that at one point in time it was integrated within the existing site, thus the entire architectural layout at Dash Kasan was comprised of a central rock-cut vault flanked by two peripheral rock-cut spaces so that the whole complex was linked to the undiscovered southern site.

A view of the southern rock-cut site (left), and the remains of cuboid cut stones in it (right) (Photo by Amin Moradi 2020)

5 Why Dash Kasan cannot be a Buddhist monastery

Rashīd al-Dīn (1994: 88) and Kāshānī (1969: 56) provide some evidence that there was a place of worship (bandaqi) in Qunqūr Ulāng attended by both Ilkhans and bakhshīs (a Buddhist lama or scholar in particular during Mongol hegemony in Iran).Footnote 12 However, we should be open to questioning the accuracy of the current opinion that Dash Kasan itself stood at the believed site of the bandaqi. But if it still did, notwithstanding the fact that bandaqi was not necessarily a rock-cut architecture, we are permitted to believe it did not, because of probabilities referring bandaqi to any brick-based construction in the historic fabric of the Sultaniyya plateau. Moreover, Rashīd al-Dīn’s description could only point to a focus on the population in the Ilkhanid Capital, Sultaniyya, where the Buddhist community exists (Prazniak 2014). According to Rashīd al-Dīn, Qunqūr Ulāng was the summer destination of the Mongols (yaylāq) (Rashīd al-Dīn 1994: 1311). In Tārīḫ-i Mubārak-i Gāzānī, he mentioned that Arghūn spent the winter lodging around Arrān (qishlāq), in what is now the Republic of Azerbaijan, and from there he moved to the summer accommodation in Qunqūr Ulāng (Ibid: 1156). However, according to Rashīd al-Dīn, Qunqūr Ulāng and Sultaniyya have perhaps never coincided territorially and were in fact one and the same site (Rashīd al-Dīn 1994: 1134). The survival of the name Qunqūr Ulāng in the late Ilkhanid age is because of its chronicling by the historian Wassāf (Wassāf 1966: 54).Footnote 13 All of this suggests that, in addition to the name Sultaniyya, the original Mongolian name survived, at least until the end of the Ilkhanid age. It is certain that within the East Asian region, Buddhist religious influences were still important in the Ilkhanid court (Allsen 1996: 89). Sources also refer to the persecution of bakhshīs in Iran. On the other hand, the term bakhshī should also be treated with caution. Although bakhshī is the name of a representative of a religious cult in East Asia (Azad 2010), it was also used as a collective term for all non-Muslims (Allsen 1996: 158). An anecdote from Kāshānī evidence that around Sultaniyya, people of inner-Asian descent who performed shamanistic cleansing ceremonies might also have been called bakhshī (Kāshānī 1969: 89).

As aforementioned, according to some scholars, the dragon panels in Dash Kasan suggest the presence of a Buddhist monastery (Scarcia 1975; Azad 2010; Brambilla 2015).Footnote 14 The dragon motif in Dash Kasan is distinctive in that it dominates the entire eastern and western surfaces (Fig. 7). Although Azad (2010) introduced Dash Kasan’s dragons as having a strong resemblance to Chinese dragons, this motif is considered auspicious in almost all parts of Asia-Pacific including China, Korea, Japan, Southeast Asia, Bhutan, Nepal, India, to name but a few (Xin et al. 1988: 71; Campbell 1988: 122). Considering the Mongol empire represented the largest contiguous land empire in history, unlike Azad (2010) we are permitted to conclude that the prototype for the Ilkhanid dragon was not merely a Chinese ‘copy’ since Mongol craftsmen had a much higher status than was the case in other societies (Serruys 1959), and artisans from the four corners of the Mongol territory were free to contribute their perspectives to Mongol art. On a general level, the dragon in Dash Kasan has been fully depicted as the absorption of Southeast Asian civilisation and imported East Asian philosophies (Them and Tho 2011). Although the image of a dragon in Dash Kasan would seem to set this monument apart as a sacred place, this representation does not necessarily define it as a Buddhist monastery because, in the mythology of the Orient, the dragon is a conceptual animal that symbolises supernatural power, wisdom, strength, and hidden knowledge (Xin et al. 1988: 71; Ranjan and Chang 2010). The accurate identification of these dragons only strengthens the argument that there very probably were interactions between Iran and East Asia during the Mongol reign in Iran, the only logical interpretation of this symbol in Dash Kasan.Footnote 15

The dragon panel and muqarnas frames on the western wall in Dash Kasan (Photo by Amin Moradi 2022)

On two sides of the dragon frames in both the eastern and western faces are a series of motifs common to Ilkhanid tombstones, including muqarnas vaults which stylistically suggest an affinity to Mongol funeral art in Northwest Iran (Fig. 8). Regarding the religious background why such decorations usually adorn Ilkhanid tombstones, it will suffice to say that Mongol religious art overlaps with imperial symbols (the dragon) in Dash Kasan. This coincidence deserves special attention because this could recalibrate our knowledge about the possible function of this site. Azad (2010) equates the two circles on these frames to the turning wheel (chakra) which offers convincing clues to support a Buddhist purpose. The main weakness of this hypothesis is the failure to reflect on the thousands of tombstones of the Mongol period in Northwest Iran which feature a similar icon. Without this line of questioning, and if this appearance indicates a Buddhist identity, then all the tombstones in Northwest Iran would be considered to represent the Buddhist faith. This conclusion cannot be true for the following reasons. First, tombstones from the Mongol period in Iran usually have a higher degree of Koranic embellishment and include pious Islamic phrases which are absent in Buddhist art. Second, the Buddhist faith community was a non-Muslim minority in Northwest Iran (Ball 1968). In sum, it would not be rational to conclude that a pointed arch flanked by two circular forms necessarily indicates a Buddhist identity. The example of the same composition on the main entrance of the Geghard monastery (1215 CE) in ArmeniaFootnote 16 confirms the fact that it may have existed across and throughout the Mongol territories.Footnote 17

Left: An unfinished decoration frame from the southern wall in Dash Kasan in which the circle shapes apparently were supposed to be rosette; Right: A tombstone from the Alinja graveyard (8th /14th century) including Koranic inscriptions (Photo by Amin Moradi 2021)

Of particular interest in Dash Kasan are fragments of carved manuscripts found dumped in a field that feature Koranic epigraphs in Naskh script reminiscent of Islamic decoration. The size and legibility of this script suggest a marked attempt for it to be seen and read from a distance. Although the content is not decipherable, it is possible that this inscription was arranged to be set on the disappeared main (southern) niche, as is characteristic of Ilkhanid structures.Footnote 18 This notwithstanding, it is doubtful that an Islamic inscription wouldn’t be in line with the architectural goals of a Buddhist monastery. Furthermore, we do not have detailed information on the overall architectural layout of Buddhist monasteries in Iran to support this claim that the current architectural arrangement provides precious information pertaining to a Buddhist monastery. Strictly speaking, the architectural layout in Dash Kasan does not necessarily reflect that of a Buddhist monastery. Or alternatively, not all Buddhist architecture can be called a monastery, “since a complete Buddhist monastery should fulfill at least the following three conditions: it should be a fixed space dedicated to worship; a place capable of hosting a substantial number of resident monks or nuns; and a place where rituals are regularly performed” (He 2013) and where enough space is given over to this purpose.Footnote 19 If we accept the idea that Dash Kasan was a Buddhist monastery, a probable link could be suggested with the monasteries of China, Korea, and Japan due to the cultural contacts established by the Mongol invasion of Iran (1219–1221 CE). When we study the spatial composition of a Buddhist monastery in East Asia, under normal circumstances, the following discrepancies with the Dash Kasan site. The main entrance of Buddhist monasteries is typically located on the south side of the monastic complex (He 2013), whereas in Dash Kasan, there are no remains to mark such an entrance. Even if one existed, it must have been situated to the north in the only possible location.Footnote 20 Almost all Buddhist monasteries included a perimeter wall that served as the outer boundary, as well as a portico set therein that could be used to separate different compounds within it (Mizuno 1969; Shoshin 1974). Dash Kasan was never surrounded by such a wall. Another structure that is missing in Dash Kasan is the roofed corridor normally used to connect different structures in a Buddhist monastery (Xiao 2003a: 56). The pagoda in Buddhist monasteries marked the place where Sakyamuni’s śarīra (Buddhist relics) was cited. As the most important building of the monastery, the pagoda was placed at its center (Nakamura and Okazaki 2016). The lack of such a space at Dash Kasan raises questions. Furthermore, architectural remains in Dash Kasan do not contain the basic architectural arrangement including large halls, dormitories, libraries, drums, and bell towers which have special religious functions and are essential for the running of a monastery (Xiao 2003b: 70; Gildow 2014; Xu 2020; Sørensen 2021). Considering the essential requisites of a Buddhist monastery, a more complicated question to ask is: where were the residence rooms for monks and pilgrims? Taking into account the tribal nature of the Mongol lifestyle (Tesouf 2009: 102), one might propose the possibility of moveable residences like yurts (ger), which are used as dwellings by several distinct nomadic groups in the steppes of Central Asia as an alternative for lodging places (Steinhardt 1988). This is certainly possible, but unlikely or at least uncommon in connection with a permanent building like a monastery. Even if this had been true, there are no remains that can support the eulogium referred to. If the caves in Dash Kasan are to be deemed a vihara archetype (Azad 2010) and were constructed simply for the lodgment of status or idols, there were no cells planned for the occupants. We should here mention the viharas of Darunta and Hadda in Afghanistan that are rock-cut and which can more positively affirm that a succession of cells formed in the rock overhanging the river provided residence facilities (Masson, 2017: 16). It is also worth noticing that temples and monasteries are roofed structures and are not open to the sky (Gao and Woudstra 2011). The evidence from archaeological investigations indicated no remains of heating units or even a centimeter of ash layer in Dahs Kasan (Mirfattah 1997). This is very indicative if one refers to Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo’s (died 2 April 1412) detailed report of Sultaniyya’s extremely harsh winters (Clavijo 2002: 137). Hence, the critical question still remains: how is it possible to conduct daily rituals in such an open area, without any heating facilities, if the climate is wet and rainy for nine months of the year? The idea of a seasonal monastery is not really plausible since this would detract from the holiness of such a place. Therefore, the identification of Dash Kasan as a Buddhist monastery cannot really be considered more than a rudimentary hypothesis.

6 Discussion

The implemented quarrying techniques in Dash Kasan present no remarkable feature, or at least any sufficiently so, to be able to deduce a particular time span. However, if it is contemporaneous with the most venerated Ilkhanid ruler of the region, Arghūn Khan (1258–1291 CE), the longest period as a Khan in the Ilkhanid Dynasty, then we can evaluate this hypothesis that the construction process in Dash Kasan had never ended due to an outright contradiction between the highly decorated frames of upper elevations and a messy stone floor. A photograph taken of the west wall makes the architectural progress clear (Fig. 9). On the question of the construction method in Dash Kasan, the existence of unfinished frames beneath the dragon frames, as well as incomplete muqarnas frames, the idea that carvers started at the top of the original rock and excavated downward could be put forward. If this was not the case, then carving included architectural baselines and decorations simultaneously. It is also possible that this discernible phase of quarrying activity at Dash Kasan was initiated with the intention of further enlarging the monument as well.

A citation attributed to Ghazzn Khan (r. 1295–1304 CE) in Jami’ al-Tawarikh (Compendium of Chronicles) affirms his interest in demolishing all of his predecessors’ non-Muslim constructions throughout the Ilkhanid realm after his epic conversion to Islam in 1295 CE (Rashīd al-Dīn 1997:657). From this point of view, Dash Kasan could exemplify a rigorous destruction undertaken by Islamic society of a monument that did not exhibit the themes of Islamic architecture. But this hypothesis is not devoid of important misconceptions as there is, logically, no need to cut a block of stone free from the bedrock in partly regular geometric shapes if the overall intention is to cause deliberate destruction or damage. As aforementioned, it is very probable that the quarrying process in Dash Kasan belonged to a post-Ilkhanid period in which the stone bed of the earlier construction was extracted to be reused in other projects, the repeating history in architectural heritage. As seductive as this hypothesis might be, serious holes begin to form in it if and when the hundreds of stone blocks scattered around the surrounding fields are taken into account: if the purpose was to support a post-Ilkhanid project, these stone blocks would likely have been transferred after the extraction.

Incomplete panels and decoration in Dash Kasan in which the continuity of vertical lines is interrupted at the bottom (Photo by Amin Moradi 2021)

As mentioned earlier, the central floorplan in Dash Kasan represents the main space flanked by two smaller ones. Archaeological excavation of the imperial Mongolian complex at Kondui (Kradin and Kradin 2019), in the vicinity of Qara QourumFootnote 21 - the first Mongol capital, headed by Sergei Kiselev in 1948 - revealed a fairly similar structure built upon a rammed-earth mound (Bemmann and Reichert 2020) (Fig. 10). Kiselev suggests that there might have been tent sites around the building (Ibid), and this composition resembles those of the tent mounds at Qara Qorum’s palatial buildings. He then concluded that this layout reflects the imperial prestige of Chinese-style prototypes. Unfortunately, historic accounts do not provide any specific information about Dash Kasan. Although there is no indication of the name of an imperial occupant for this place in any historical texts, the geographical location in which the building is situated provides some clues. In Shangdu, an imperial palace commissioned by Möngke Khan in dedication to his brother Kublai Khan in 1256 CE, the palace enclosure is known as Qong Cheng (Steinhardt 1988). The terms Huang Cheng and Da Cheng have literally been translated as an administrative sector and the outer area respectively (Ibid). Since the suffix Cheng indicates the location of a city in the Chinese language, therefore the word Qong in Qunqūr Ulāng might denote a palace. Ḥamdallāh Mustaufī mentioned that this place was used as a location for hunting falcons (Mustaufī 1983: 55). This statement would suggest more clues that Qunqūr Ulāng was designed for imperial uses. Rashīd al-Dīn’s brief reports of Shangdu palace in Jami al-Tavarikh confirm its function as a hunting park where falconry was the main entertainment of the Khagan (Rashīd al-Dīn 1997:657). In his report on Anxi Wang Fu, the Mongolian palace excavated by Chinese archaeologists and dated to 1275 CE, Marco Polo wrote: “… there are most amazing hunting parks and palaces for hawking in this area” (Polo 1958: 67).

It is tempting to see a connection between pre-Mongolian royal buildings and Dah Kasan, even if it is not a direct one. In Dash Kasan the most prominent niche is on the south wall and is higher than the other spaces. The height of this platform may suggest that the main purpose of this space was to be seen from the other points of the site. This architectural form (the main niche flanked by two bilateral niches) has several immediate historical precedents in Mongol territories. In his itinerary to Mongolia, William Rubruck describes Möngke Khan’s (r. 1251–1259 CE) audience hall in the following way: “… and the palace has a plan like a church including a middle nave, and two bilateral spaces. The Khan sits in the main place to the south which is higher than the others and thus can be seen by all. Here, envoys of different nations give their presents to the Khan who sits up there like a divinity. On the right hand, that is to the west, are the men, and the women are on the left. The palace outstretches from the north to south” (Rockhill 2010: 209). Ala al-Dīn Atā-Malik Juwainī (1226–1283 CE), also provided a similar description of the Möngke Khan’s palace in his Tārīkh-i Jahāngushāy: “… inside a huge garden a palace was built for Khan (Möngke) with three spaces. While the throne was located in the middle, the right and left houses were for his brothers and sons and his ladies… twice in the year would Khan appear in this pleasant abode” (Juwainī 1978: 766).Footnote 22

The dragon is usually associated with royal and imperial contexts (Tcho 2007). Dragon reliefs in Dash Kasan find similar parallels in the Mongol royal palace of Qara Qorum, Shangdu,Footnote 23 as well as in the Kubilai’s main hall of audience the palace in Dadu (Steinhardt 1988),Footnote 24 the second Mongol capital. If one turns to Juwainīs’ quote that “craftsmen from China (Khitay) are singled out between the others in the construction of Qara Qorum palace” (Juwainī 1978:766), it is likely that these motifs were the result of the involvement of Chinese masters.Footnote 25

It is also important to add that the Zanjān area played an important role in Hülegü’s (1256–1265 CE) campaign at the time of the conquest of Alamūt and other fortresses by the IsmāʿīlismFootnote 26 in northern Iran (Allsen 1996: 103). Moreover, Hülegü’s army marched on Hamadan by touching Abhar and Zanjān before conquering Baghdad in 1258 CE. It is therefore probable that Sultaniyya was the location of the annual migration of Mongol rulers before Arghūn Khan’s enthronement in 1284 CE (Rashīd al-Dīn 1994: 1315). All of this suggests that the location of Dash Kasan conveniently serves an imperial function and the Mongols had compelling reasons to use it before the construction of the later Ilkhanid capital, Sultaniyya.Footnote 27 Several historic accounts have pointed to the importance of ceremonies at the Ilkhanid court (Juwainī 1978: 776, Polo 1958: 66; Rashīd al-Dīn 1994: 1156), and these ceremonies were an important opportunity for the Khans to present themselves in a position of authority (Rashīd al-Dīn 1994: 1157). The architectural parallels strongly support the conclusion that the ground plan of Dash Kasan reflects the design of a Chinese-style ceremonial hall. In the East Asian cultural sphere, ancestral rites are religious practices that originated as acts of worshipping the dead, but which were gradually integrated with political ideology for the protection and control of state power, thereby becoming rituals led by the state. Because of this close relationship between ancestral rites and the state, an altar where the rite was performed came to be regarded as an essential national facility (Park 2018). Undoubtedly, the existence of altars was an important feature that not only symbolized the power of the kings in East Asia, but also represented the status of the capital city (Hyeryun 2015). According to historical accounts and archaeological evidence, it was during the first millennium BCE that the first altar was built in China (He 2013). This archetype was continued after the Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty (960–1279) beginning under Ögedei Khan (r. 1229–1241) (Ikchul 2001: 529). In “The secret history of the Mongols”, sacrifice to the ancestors came to represent the core of religious belief (Rachewiltz 2015: 41). Surprisingly, a close link existed between the Song Dynasty’s (960–1279) altars and Dash Kasan. The overall arrangement of an altar during the Song period included a central hall in the south of the site flanked by peripheral halls (Park 2018), presenting strong similarities with Dash Kasan (Fig. 11). It is, therefore, not an exaggeration to consider that Dash Kasan basically inherited the pattern of Chinese architecture in the rock-cut shape. This architectural layout is also reminiscent of the pattern of Ming Dynasty ceremonial halls (1368–1644 CE) in which the main axial hall was connected to the left and right-side halls (UNESCO, 2000). The presence of a tomb mound in the rear of the central hall belonging to the royal family or king’s concubines (Ibid), would attract attention to the exact identity of the site in the main axis of Dash Kasan. Ilkhanid sources indicated that a bias in favor of a hidden location on top of mountains is given preface over the normal burial customs,Footnote 28 a policy hitherto known before Ghazan’s conversion to Islam in 1295 CE.Footnote 29 The cultural significance of tomb monuments, before and after the Mongol conquest, is alluded in Jami al-Tavarikh: “…Until now it has been the custom of the Mongol emperors of Genghis Khan’s urugh [lineal descent] to be buried in unmarked mountains far from habitation in such a way that no one would know where they were … When he [Ghazan] became Muslim … he said, ‘Although such was the custom of our fathers … there is no benefit in it. Now there we have become Muslim and we should conform to Islamic rites” (Rashīd al-Dīn 1994: 997). In concordance with this attitude, albeit not with the same coherence and quality as Ghazans’ tomb, an unprecedented number of religious projects were undertaken during the Ilkhanid dynasty (Brambilla 2015). We must thus conclude that Mongol royal tombs after Ghazan are zenith towering mausoleums, while their predecessors, like Hülegü and Arghūn, are buried in hidden locations in rock-cut burial chambers (Wilber 1969: 198).Footnote 30 At a glance, the rear area that remains some 200 meters behind the current structure in Dash Kasan has enough potential of being considered the hidden place of a burial chamber due to the mountainous landscape. More importantly, comparable forms of this layout were employed in Chinese ceremonial halls and the probable surrounding area of the tomb in a wider context.

Another clear architectural parallel for a central space flanked by two peripheral rooms can be traced in the Temple of Heaven (1420 CE) which is located in the southeastern part of an area that was originally the outer city of ancient Beijing. This monument represents the largest existing building complex, not only in China but throughout the world, for holding sacrificial ceremonies during ancient times (Casson 1955). Apart from the Temple of Heaven, there are eight other imperial sacrificial altars in ancient Beijing that are mainly designed in a three-tiered square platform (Gao and Woudstra 2016).Footnote 31 Among these altars, Xiannongtan (the altar of the God of agriculture) bears the closest resemblance to Dash Kasan. Xiannongtan was the site of imperial sacrifices dedicated to the cult of Shennong, the legendary “first farmer” of China (Bao 2005: 39). Ancient China was an agricultural society. The people felt great reverence for the land and grain and elevated these things to the status of gods. Similarly, in Varāy (Viyar) which is blessed with huge amounts of fertile land and rich mineral deposits, farmers offer prays to the god through annual ceremonies around Dash Kasan. Considering the magnificence location of Dash Kasan in the Sultaniyya plateau, one might even go so far as to say Dash Kasan may have provided a platform for “observing the harvest” for the Mongol Khan, as was the case in Chinese examples.Footnote 32 In short, this site promises some indication for bridging the gap between Chinese-style ceremonial halls and the original function of Dash Kasan. However, owing to insufficient archaeological excavations, some understandings are still limited, and therefore the in-depth understanding of this monument is still waiting to be supplemented by further examination and more archaeological discoveries.

Ming’s Dynasty tomb layout in which the second courtyard consists of a central hall and two side halls. A Xiaoling (1368 CE), B Changling (1402 CE), C Yongling (1566 CE), and D Dingling (1602 CE); E The Temple of Heaven (author’s drawing based on (UNESCO, 2000); F The simplified plan of Dash Kasan (Drawing by Amin Moradi)

There are several possible explanations for this architectural transmission from China to Iran. As historical evidence attests, by 1279 CE, the Mongol leader Kublai Khan (r. 1260–1294 CE) had established the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 CE) in China and crushed the last Song (960–1279 CE) resistance, and all of China fell under the Mongol Yuan rule (Allsen 1996: 10). This was the first time in history that the whole of China was conquered and subsequently ruled by a foreign or non-native ruler (Boyle 1968: 343). Traditional Chinese historians described the Mongol-ruled Yuan DynastyFootnote 33 as having ravaged Chinese territory and decimated the Chinese population by fostering the development of a more despotic rule in Ming China, causing many talented men to avoid government service (Rossabi 2013: 223). Due to this artistic strategy, Chinese craftsmen spread out all around the Mongol territories which transmitted Chinese ideas into foreign lands (Serruys 1959, Allsen 2009: 52). Steinhardt (1988) has suggested that, ironically, the Chinese-style architecture that the Mongols imitated proved to be a successful vehicle or legitimation of the Ilkhanid court’s rule. This is due to the fact that the Ilkhanates, like the Golden Horde and Chagatai Khanate, initially recognized Qara Qorum as the supreme capital of their empire (Steinhardt 1988).

The multinational makeup of Dash Kasan’s community of craftsmen is also confirmed by the stone fragments left in situ, indicating the involvement of craftsmen familiar with stone structures (Fig. 12).Footnote 34 The school of origin for these decoration bands appears to have been Armenia,Footnote 35 since they strongly recall the decoration of monasteries at Hohanavank (1215 CE), Ejmiatzin, Goshanavank (12th – 13th centuries), Sanahin (10th – 13th centuries), and Haghartzin (13th century) in every aspect. It is therefore conceivable that, due to the economic and political changes, the Armenian diaspora was part of Ilkhanid society or that Ilkhanid patrons invited masters from this region into the Ilkhanid capital of Sultaniyya to carry out architectural projects. However, in designing the ground plan, it was China that they turned to for the most powerful visual imperial symbols offered by East Asia. These crafts supplemented the lack of artistic aspects in the Mongol’s nomadic life. The confirmable presence of masters from Armenia and China emphasizes the fact that the construction and decorative arts in Dash Kasan each had their respective origins.Footnote 36

Stone-carved decoration in Dash Kasan (A) (Digital collection of Cultural Heritage and Tourism Organization; Iran); Hohanavank monastery (B), and Sanahin monastery in Armenia (Photo by Amin Moradi 2021)

7 Conclusion

In the absence of any convincing evidence to suggest a covered area, it must be concluded that Dash Kasan was used for temporary activity rather than as a continuously occupied Buddhist monastery. The arrangement of three rock-cut niches in Dash Kasan represents Mongol royal buildings that can be seen in the imperial city of Qara Qurum like Möngke Khan’s (r. 1251–1259 CE) audience hall. It also bears a close resemblance to the Chinese architectural formation reserved for high-ranking structures which were built in successor states of the Mongol Empire after its division in 1259 CE. In other words, Dash Kasan was the outcome of a major event of cultural exchange between Iran, Mongolia, and China, which occurred in the Ilkhanid dynasty (1256–1335 CE) to balance the relationship between these regions. Otherwise, the ground plan of Dash Kasan echoes a pre-Ilkhanid royal building from which the Ilkhanid Khans in Iran could make their bid for the Great Khan (Khagan) of a universal Mongolian empire with a reliance on Qara Qorum as its administrative center and focal point. Although political rivalry was inevitable between these khanates, mutual land borders between Ilkhanate, Golden Horde, and Chagatai Khanate, as well as a network of land and sea trading routes - the Silk Road- provided an avenue for all sorts of creative exchange between tremendously diverse peoples and cultures. From this point of view, the diversity of architectural forms in these regions is not unexpected. It is also known that master builders often worked far from their place of birth or their native land and, as such, diverse architectural traditions survived in many regions of the Ilkhanid Empire.

Although it is not clear which event halted the construction project in Dash Kasan, the architectural layout of this site finds its roots in examples of royal buildings in Mongolia and China, going back as far as the thirteenth century. The connections with Chinese-style ceremonial halls are indeed compelling to put forward the hypothesis that the rear rock-cut remains in the central axis of the main niche in Dash Kasan could belong to a Khan’s concubines or other family members. Even though the location of the site in the vicinity of Āq DāghFootnote 37 (Safīdkūh) Mountain could increase the veracity of the claim that it is an Ilkhanid royal tomb, this hypothesis is still waiting for further archaeological confirmation. Situated on bluffs along the nearby river that afforded vistas over the Sultaniyya grass, Dash Kasan took full advantage of the available space and landscape in the region to effectively represent Mongol sovereignty. From this point of view, Dash Kasan was never in use as a Buddhist monastery.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Sultaniyya is a town in Northwest Iran that is located some 50 km to the southeast of Zanjān province. Sultaniyya was founded towards the end of the 7th/13th century by the Mongol Ilkhanid and served for a while in the following century as their capital (Le Strange 1905: 224).

For measurements of the Gaz and Gam see: Golombek and Wilber 1989. The Timurid Architecture of Iran and Turan. Princeton: Princeton University Press. P. 145, 259.

On the construction of Sultaniyya, Ḥāfeẓ-e Abru quotes Öljaitü as saying that: “One day I was with my father Arghūn Khan who was known for being righteous and knowledgeable. He claimed to build the city of Sultaniyya. People who were present suggested different places. He finally chose Qunqūr Ulāng, which is a very pleasant summer quarter” (Ḥāfeẓ-e Abru 1992: 8).

Today, what is left of the main tower and fortress of Sultaniyya city consists of at least six rows of stones of varying length and a fixed height of 59 cm, executed in a green limestone environment approximately 1400 m in length.

Aside from the fortification, the stone materials used in the construction of the Masjid-i Juma (congregational mosque), Teppe Nur, and Kabud Gunbad in Sultaniyya are very similar to the green tuffite stone blocks of Dash Kasan (Naiemi 2020).

Place names are social signals of belonging to a group or culture (Helleland et al. 2012). Among the numerous place names around the site, “Veek” indicates a close linguistic link to the name of the village of Varāy (Viyār), which is located some 6 km to the south. It is therefore possible to propose the idea that they are part of a language rather than a place.

It is hard to assert that there is no ideology behind this representation; one probable interpretation could be the deep involvement of Turkic tribes in their mythological attitude (Esin 2004: 16). On the importance of directions in both the pre-Mongol and Mongol dominions, it suffices to say that the main axis of imperial structures, at least in Northwest Iran, typically follow a north-south orientation. Gonbad-e-Sorkh, Alaki Caravanserai, Sarcham Caravanserai, Ghafariye Dome, and Gonbad-e-Kabud in Northwest Iran give credence to this assertion.

Taḵt-e Solaymān is an outstanding archeological site with substantial Sasanian and Il-khanid ruins in Azerbaijan, between Bijār and Šāhin-dež, about 30 km north-northeast of Takāb, at about 2,200 m elevation, surrounded by mountain chains of more than 3000 m height.

The later findings at Dash Kasan, including sporadic blue and white porcelains from the Timurid (1370–1507 CE) and Safavid reigns (c. 1501–1735 CE), attest to post-Ilkhanid activities at this site (Mirfattah 1997: 55). One might consequently argue that the monument was undoubtedly visited by post-Ilkhanid successors, but there is little evidence that it played an important role in the timeframe studied and never recovered its early glory contemporaneous with the Mongol ages.

The nomenclature Dash Kasan can be traced across almost all of Northwest Iran. The primary reason is that the name Dash Kasan, which means stone-quarry in the Turkic language, fits well with the importance of these villages as stone mines. Dash Kasan villages in Azar Shahr, Miyaneh, Ahar, Hashtrood, Maraghe, Sanandaj, and Maku provide evidence for the fact that the naming of these villages was associated with their function as stone quarries.

All measurements were carried out in a TL lab located in the research institute of cultural heritage and tourism, Iran, using ELSEC 7188 Automated TL system.

The word bakhshīs appears only later, in the writings of Rashīd al-Dīn Fażl-Allāh and Wassāf. The period covered by these authors, that of the Ilkhan Hülegü (Hūlāgū) and his successors, witnessed the brief emergence of Buddhism, for the last time, as a major religion in Iran; it was facilitated by the tolerant attitude of the Mongol rulers towards the representatives of all religious groups and sects, and by the fiscal exemptions granted to them (Spuler 1985: 155).

Abdallah ibn Faḍlallah Sharaf al-Din Shīrāzī (fl. 1265–1328) was a 14th-century Persian historian of the Ilkhanate. Wassāf, sometimes lengthened to Wassāf al-Ḥaḍrat or Vassaf-e Hazrat (Persian: وصّافِ حضرت), is a title meaning “Court Panegyrist”.

Wassāf wrote:

بر اقاليم جهان يافت شرف قنقور اولانک تا که شد تختگه پادشه روی زمين.

“Qunqūr Ulāng found nobility on the continents of the world /until on the ground it became a royal throne.”

It is thought that the dragon is an example of the remarkable integration of Buddhism into different cultures (Tcho 2007).

In 2014, Tho tried to categorize the dragon motif in East Asia based on its aesthetic expressions. He recorded three distinct forms of the dragon; The first configuration, which mainly dates to the 11th-13th centuries, features long snake figures with a zig-zag patterned, curly body depicted running top to bottom. According to Tho, during the next period (13th-14th century), the dragon’s body became bigger, the head and the neck were irregularly changed while the dragon’s tail stretched in a horizontal axis (Tho 2014: 23). Finally, from the 15th century onward, the dragon image was greatly influenced by the local futures and naturally faded (Ibid). Examining all possible forms of the dragon in luster-decorated pottery tiles from Taḵt-e Solaymān (c. 1270–1280), the Ilkhanid summer palace, casts doubt on this assumption by suggesting that artistic expressions of the dragon in Ilkhanid Iran depended more on artists’ personal tastes rather than a specific rule. Hence, the dragon frames in Dash Kasan do not necessarily refer to a historic era nor a specific region.

Armenia was a tributary of the Mongol empire from 1236 CE until around 1335 CE (Prezbindowski 2012). The most informative Armenian sources are the Patmutiwn Hayots (History of the Armenians) written by Kirakos of Ganjak (1200–1271 CE) and the Tatarats Patmutiwn, more commonly known as ‘the History of the Nation of Archers’ written by Grigor of Akner (1250–1335 CE). See: Kirakos of Ganjak, History of the Armenians. 1963. trans. John Andrew Boyle. Central Asiatic Journal 3 (3): 251 − 245; Grigor of Almer, History of the Nation of Archers (the Mongols). 1949. trans. Robert P. Blake, Richard N. Frye. HJAS 12 (3):269–399.

It is surely worth asking what the message being transmitted through these icons is. As I have discussed elsewhere (2018), in the case of tombstones, it might indicate the gender of the deceased: double-circle tombstones mark the grave of a man, while a single rosette tombstone suggests a woman’s burial. This tradition is still followed in some remote villages of Northwest Iran today.

In the mausoleum of Mir Khatun (8th /14th century) at Salmas, Northwest Iran, the inscription looks to have been assembled from separate stone plaques, a tradition copied from the Sarcham Caravanserai (1333 CE) in which two rows of stone plaques featuring the same calligraphy indicate Abu Said’s realm (1335 CE) (Moradi 2021: 98).

Although Blair (2014) suggested that a vast yard flanked by two covered, colonnaded aisles was once arranged around a rectangular courtyard, there is no evidence to confirm that these pillars were implanted into the base or even cut through the rock bed. Furthermore, there is no surviving sign of a column grid.

Although according to Azad (2010), the open space, at the lowest level, gives the impression of having been a grand entrance, there is no sign of any attempt to create an entrance in this section.

Although Qara Qurum was used by the Mongols at the time of Chinggis Khan, Qara Qurum’s most important patrons were Chinggis’ third son and successor, Ogodei (r. 1229–1241 CE), Ogodei’s son, Guyug Khan (r. 1246–1248 CE), and Chinggis’ grandson, Möngke (r. 1251–1259 CE) (Steinhardt 1988).

Placing tents symmetrically in relation to the main construction line is a pattern which appeared at Qara Qurum and Dadu before permanent buildings were established (Steinhardt 1988). One might then conclude that tent dwelling was a standard installation at imperial Mongolian sites and a practice the Ilkhanates in Dash Kasan followed.

Marco Polo describes this palace in the following way: “On top of each pillar in this palace, there is a well-polished dragon hewn from rock which stretches their arms and hold the ceiling with their heads” (Polo 1958: 186).

According to archaeological evidence, Ögodei summoned hundreds of craftsmen and artisans from China to Qara Qorum to erect the ruler’s residence in this city (Barkmann 2002). In 1267, when much of China was part of the Mongol Empire, Kublai Khan (r. 1260–1294) put the Arab architect Amir al-Din in charge of the construction of his new palace at Dadu (Khanbaliq, now Beijing), the “Grand Capital” of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) (Luo 2021).

At the Quriltai of 1251 CE, the Great Khan Möngke decided to compete and consolidate the Mongol conquests by dispatching his brothers, Kublai and Hülegü, to China and Western Asia respectively. Hülegü’s first instructions were to destroy the Isma’ilis and demolish their castles (Boyle 1968: 340).

Ismāʿīlism is a major Shiʿite Muslim community. The Ismaʿilis have had a long and eventful history dating back to the middle of the 2nd/8th century when the Emāmi Shiʿis split into several groups on the death of Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādeq. The earliest Ismaʿilis from amongst the Emāmi Shiʿis traced the imamate in the progeny of Esmāʿil b. Jaʿfar al-Ṣādeq, the eponym of the Esmāʿiliya (Daftary 2000; 114).

It is also noteworthy that a late Yuan Chinese map drawn up in roughly 1350 CE shows Sultaniyya, which suggests that the Mongol empire had close ties along the Silk Road with the two successor states of the global empire (Azad 2011: 230).

See: Bausani 1968. Religion under the Mongols. Ed. Boyle, J. A., United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Ghazan Khan initiated a major reform of burial practices and erected a gigantic tomb tower for himself in Tabriz, the second capital of the Ilkhanid Empire. Rashīd al-Dīn reported that: It was constructed in the suburb of the city in the western part of Tabriz in the position of “Sham” that he himself [Ghazan] had designed and built” (Rashīd al-Dīn 1994: 997).

Considering the burial history of pre-Ghazan ages, and as historical texts confirm, Hülegü Khan was buried in 1265 in a mountain on the island known as The Shahi Island, which literally translates to Royal Island (Wilber 1969: 198; Sanders 1996: 90). Attempting to identify the location of the burial place of Arghun, Brambilla (2015) believed there were sufficient descriptions indicating that he was buried in an unmarked location in the mountains of Sujas, but Mustaufī-e-Gazvini, in his Nuzhat al-Qulub, reported that: “He (Arghun) was buried in an incognito place until his daughter Uljai Khatun revealed the location and established a monastery there” (Mustaufī-e-Gazvini 1913: 64). Fasai’s accounts in Farsname-e-Naseri reveal that Arghun’s tomb was plundered by raiders in 1847 (Fasai 2003: 707).

There are several altars in China where rituals used to be performed by the emperor. In Chinese culture, an altar (tán 壇) is sacrificing ground as defined by Shuowen jiezi, the oldest surviving Chinese dictionary dating to 100 AD. See: Gao and Woudstra 2016. Altars in China. In: Selin, H. (eds) Encyclopedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7747-7_9815.

See: Bao 2005. Hawai‘i Reader in Traditional Chinese Culture. Victor H. Mair, Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt and Paul R. Goldin. (eds). Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press.

By the time of Kublai’s death, the Mongol Empire had fractured into four separate khanates, or empires, including the Golden Horde in the northwest, the Chagatai Khanate in Central Asia, the Ilkhanate in the northwest (now modern-day Iran), and the Yuan Dynasty in the east (Allsen 1996: 10).

In this regard, Wassāf (d. 1329 CE) mentioned that a large number of skilled craftsmen migrated to this region with their families and contributed to the construction of architectural projects (Wassāf al-Hazara 1967: 277).

For example, evidence that Armenians were working and living in the new Ilkhanid capital, Sultaniyya was discovered by Marco Brambilla in a large-scale Armenian cemetery on the nearby plain See: Brambilla 1980. La communita ed il cimitero Armeno di Sultaniya, Studi e Restauri di Architettura, Italia-Iran. Italy. P. 87–93.

The evidence that masters from all over the Mongol territories arrived in the Ilkhanid capital of Sultaniyya and were presumably active in the construction of Dash Kasan offers considerable support to Thomas Allsen’s hypothesis emphasis on the grand scope with which specialists, in particular artisans and masons, were dispatched over huge distances (Allsen 2002:174).

The Sultaniyya plateau was cut off towards the north by the Āq Dāgh Mountain (Safīdkūh) range, which reaches approximately 3000 m in elevation. This mountain separates the wooded landscapes of Northwestern Iran from areas of cultivable lands.

References

Allsen, T.T. 1996. In The courts of the Il-Khans (1290–1340), ed. J. Raby and T. Fitzherbert. Oxford: University of Oxford.

Allsen, T.T. 2002. Technician transfers in the Mongolian Empire. The Central Eurasian Studies Lectures 2. Bloomington: Indiana University.

Allsen, T. T. 2009. Mongols as vectors for cultural transmission, in The Cambridge History of Inner Asia. The Chinggisid Age, eds. Nicola di Cosmo, Allen J. Frank, and B. Peter, and Golden. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Azad, A. 2010. Three rock-cut caves sites in Iran and their Ilkhanid Buddhist aspects reconsidered. In Islam and Tibet interactions along the musk routes, ed. A. Akasoy, Ch. Burnett, and Yolei-Tlalim. R. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Company.

Azad, Arezo. 2011. Three rock-cut cave sites in Iran and their Ilkhanid Buddhist aspects reconsidered. UnitedKingdom: MPG Books Group.

Ball, W. 1968. Some rock-cut monuments in southern Iran. Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies 24 (1): 95–115.

Bao, L. 2005. Hawai‘i Reader. In Traditional chinese culture. Ed. Victor H. Mair, Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt, and Paul. Goldin. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press.

Barkmann, U. 2002. Qara Qorum (Karakorum). Fragmente zur geschichte einer vergessenen Reichshauptstadt. In Helmut Roth and Ulambayar Erdenebat (eds.), Qara Qorum-City (Mongolia) I. Preliminary Report of the Excavations 2000/2001, pp. 7–20. Bonn Contributions to Asian Archaeology, vol. 1. Bonn: Vfgarch-press.

Bausani, A. 1968. Religion under the Mongols. Ed. Boyle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bemmann, J., and S. Reichert. 2020. Karakorum, the first capital of the Mongol world empire: an imperial city in a non-urban society. Asian Archaeology 4: 121–143.

Blair, S. 2014. Text and image in medieval persian art. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Boyle, J. A. 1968. The Cambridge history of Iran. Vol5. The Saljuk and Mongol periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brambilla, M. 1980. La communita ed il cimitero Armeno di Sultaniya, Studi e Restauri di Architettura, Italia-Iran. Italy.

Brambilla, M. 2015. Tepe Nur, an unknown Ilkhanid monument in Sultaniyya. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Campbell, J. 1988. The power of myth. New York: Apostrophe S. Productions.

Casson, H. 1955. The temple of heaven. Peking Architectural Review 118: 400–401.

Clavijo, Ruy Gonzalez De. 2002. Narrative of the Embassy of Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo to the Court of Taimour: At Samarcand A.D. 1403–6. London: Hakluyt.

Çobanoclu, A. D. 2021. İlhan Doneminden bir kaya oyama yapisi: Sulyaniye Taskesen. [A rock carving structure from the ilkhanid period: Sultanite Dashkasan]. Sanat Tarihi Dergisi 1(30): 741–785.

Daftary, F. 2000. Moṭālaʿāt-e Esmāʿili. Iran Nameh 18: 257–271.

Esin, E. 2004. Turk Sanatinda Ikonografik Motifler. Turkey: Kabalci Yayinevi.

Fasai, H. 2003. Farsname-e-Naseri. Tehran: Amir Kabir.

Ganjavi, S. 1974. Dash Kasan; Shirin and Farhad. Qom: Feyziyya School Publication.

Gao, L., and J. Woudstra. 2016. Altars in China. In Encyclopedia of the history of Science, Technology, and Medicine in non-western cultures, ed. H. Selin. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7747-7_9815.

Gao. L, and Woudstra. J. 2011. From the landscape of gods to landscape of man: imperial altars in Beijing. Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes 31(4): 213–268.

Gazvini, Hamdallāh Mustaufī. 1987. Nuzhat al-Qulub. Ed. Muhammad Dabir-e-Siyagi. Tehran: Tahuri.

Gildow, M.D. 2014. The chinese buddhist ritual field. Journal of Chinese Buddhist Studies 27: 59–127.

Golombek, L., and D. Wilber. 1989. The Timurid Architecture of Iran and Turan. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Grigor of Almer. 1949. History of the Nation of Archers (the Mongols). trans. Robert P. Blake, Richard N. Frye, Grigor of Almer’s History of the Nation of Archers (the Mongols), HJAS 12 (3): 269–399.

Ḥāfeẓ-e Abru, Abdallah. 1992. Zeil Jami al-Tawarikh. Ed. Khanbaba Biyabani. Teharan: Sherkat-e-Elmi.

He, L. 2013. Buddhist state monasteries in early medieval China and their impact on East Asia. A dissertation presented to the faculty of philosophy in candidacy for the degree of doctor of philosophy. Heidelberg University.

Helleland, B., C. Ore, and S. Wikstrom. 2012. Names and identities. Oslo Studies in Language 4 (2): 95–116.

Hyeryun, L. 2015. The significance of organizing and conducting the Joseon Era Seonjamje ceremonial rites. Korean Thought and Culture 77: 173–198.

Ikchul, S. 2001. A positive study of great, medium and little sacrifice. Journal of the Humanities 31: 509–542.

Juwainī, Ala al-Dīn Atā-Malik. 1978. Tārīkh-i Jahāngushāy. Tehran: Bonyad-e Farhang.

Kāshānī, Abū al-Qāsim Abd-Allah Ibn. Muḥammad. 1969. Tārīh-i Ūljaytū. Ed. Mahīn Hambalī, Teheran: Shirkat-i intishārāt-i Ilmī wa farhangī.

Kirakos of Ganjak. 1963. History of the Armenians, Trans. John Andrew Boyle, Kirakos of Ganjak on the Mongols. Central Asiatic Journal 3 (3): 45–60.

Kleiss, W. 1997. Bauten und Siedlungsplatze in der Umgebung von Soltaniyed. Archeological Mitteilungen aus Iran and Turan 29 (9): 341–391.

Kradin, N.N. 2018. Who was a builder of mongolian towns in Transbaikalia? Golden Horde Review 6 (2): 224–237.

Kradin, N.N., and N.P. Kradin. 2019. Heritage of Mongols: the story of a russian Orthodox church in Transbaikalia. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 23: 430–443.

Le Strange, G. 1905. The Lands of the Eastern Caliphate: Mesopotamia, Persia, and Central Asia from the Moslem Conquest to the time of Timur. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Luo, D. 2021. Chinese palaces (Whiley Encyclopedia of Ancient history: Asia and Africa). Hoboken: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119399919.

Masson, Ch. 2017. The Charles Mason Archive: british library, british museum and other documents relating to the 1832–1838 Masson collection from Afghanistan. Ed. Elizabeth Errington. United Kingdom: Hockley.

Mirfattah, A. 1997. Preliminary report on the rocky temple of dash Kasan. Tehran: Research center for cultural heritage.

Mizuno, S. 1969. Mekhasanda: buddhist monastery in Pakistan surveyed in 1962–1967. Japan: Kyoto University.

Moradi, A. 2020. Archaeological Investigations in Dash Kasan. Zanjan: Cultural Heritage and Tourism Organization (Unpublished).

Moradi, A. 2021. The mausoleum of Salmas. In Reza Shirazian Ed. Reza Shirazian. Tehran: Dastan.

Moradi, A. 2022. Why the so-called Dash Kasan in Viyar was not a Buddhist temple? International journal ofhumanities 29 (1): 115–140.

Mustaufī-e-Gazvini, Ḥamdallāh. 1913. Nuzhat al-Golub. Trans. G. Le Strange. Brill: London.

Mustaufī, Hamd’ Allah, 1983. Nīzhat’ al-Gūlūb. Edited by M. Dabir. Tehran: Ebnesina Publication.

Naiemi, A. H. 2020. The Ilkhanid City of Sultaniyya: Some Remarks on the Citadel and the Outer City. Iran. https://doi.org/10.1080/05786967.2020.1744469.

Nakamura, Y., and Sh. Okazaki. 2016. The spatial composition of buddhist temples in Central Asia. Intercultural Understanding 6: 31–43.

Norallahy, A. 2011. Introduction and analysis of archaeological face reliefs from dash Kasan temple. Farhang-e-Zanjan 1 (31): 233–251.

Park, H. 2018. The historical research of the Seonjamadan altar in Seoul and the aspects of its conversion. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 17 (2): 269–276.

Polo, M. 1958. The Travels. Trans. Ronald Latham. London.

Prazniak, R. 2014. Ilkhanid Buddhism: traces of a passage in eurasian history. Comparative studies in society and history 65 (3): 650–680.

Prezbindowski. L. 2012. The Ilkhanid Mongols, the Christian Armenians, and the Islamic Mamluks: a study of their relations, 1220–1335. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1152.

Rachewiltz, I. 2015. The secret history of the Mongols: a mongolian epic chronicle of the thirteenth century. Australia: University of Wisconsin.

Ranjan, D., and Zh. Chang. 2010. The chinese dragon concept as a spiritual force of the masses. Sabaramuwa University Journal 9 (1): 65–80.

Rashīd al-Dīn Fażl Allāh Hamadānī. 1997. Jāmi‘al-Tavārīkh, ed. Muḥammad Rawshan and Muṣṭafá Mūsavī. Tehran: Nashr-i Alburz.

Rashīd al-Dīn Fażl-Allāh, M. Roshan, and M. Mousavi, eds. 1994. Jame-al-Tavarikh, vol. 2. Tehran: Alborz publication.

Rockhill. W. W. 2010. The Journey of William of Rubruck to the Eastern Parts of the World, 1253–55. Hakluyt Society.

Rossabi, M. 2013. Notes on Mongol Influences on the Ming Dynasty. In Eurasian Influences on Yuan China, 200–223. Yusof Ishak Institute: U.S.

Sanders, A. 1996. Historical dictionary of Mongolia. Lanham: Scarecrow Press.

Scarcia, G. 1975. The Vihar of Qonqor-olong; preliminary report. East and West 25 (3): 99–104.

Serruys, H. 1959. Chinese in southern Mongolia during the sixteenth century. Monumenta Serica 18(2): 50–62.

Shoshin, K. 1974. Historical approach to the layout of Buddhist monasteries and stupas at Taxila. Journal of Toho Gakuho 64: 327–359.

Sørensen, H.H. 2021. The buddhist temples in Dunhuang: Mid-8th to early 11th centuries. Buddhist Road Paper. Bochum: Ruhr-Universität Bochum.

Spuler, B. 1985. The Mongols in Iran: politics, administration, and culture of the Ilkhan period, 1220–1350. Leiden: Leiden Publication.

Steinhardt, N.S. 1988. Imperial architecture along the mongolian road to Dadu. Ars Orientalis 18: 59–93.

Tcho, H. 2007. The dragon in the buddhist korean temples. International journal of Buddhist thought and culture 8: 93–114.

Tesouf, B. Y. V. 2009. Social system of Mongols. Translated by Bayani, Sh. Tehran: Shirkat-i intishārāt-i Ilmī wa farhangī.

Them, T. N., and N. Tho. 2011. The origin of the dragon under the perspective of culturology. Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 4(1): 56–68.

Tho, N. 2014. The symbol of the dragon and ways to shape cultural identities in Vietnam and Japan. Vietnam: University of Social Sciences and Humanities.

UNESCO. 2000. Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Report of the twenty-fourth session of the World Heritage Committee. Cairns: Australia.

Wassāf, Abdallah ibn Faḍlallah. 1966. Taḥrīr-i Tārīkḣ-i Wassāf. Ed. ʿAbd al-Muḥammad Āyatī. Tehran: Bonyad-e Farhang.

Wassāf al-Hazara. 1967. Tārīkh-i-Waṣṣāf. Facsimile. Tehran: Ketāb-khāna Ibn Sīnā.

Wilber, D. N. 1969. The architecture of islamic Iran: the Ilkhanid Period. Greenwood Press.

Xiao, L. 2003a. The layout arrangement of site of Yar city. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press.

Xiao, M. 2003b. Dunhuang jianzhu yanjiu 敦煌建築研究. Beijing: Jixie Gongye chubanshe.

Xin, Y., N. Xu, and Y. Li. 1988. Art of the Dragon. Ed. Yim Lai Kuen. Boston: Shambhala Publications.

Xu, Z. 2020. Buddhist architectural transformation in medieval China, 300–700 ce: Emperor Wu’s great assemblies and the rise of the corridor-enclosed, Multicloister, monastery plan. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 79(4): 393–413.

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend special thanks to the Institute of Oriental Studies at the University of Otto-Friedrich for providing me with the resources and guidance to carry out this research. I would also like to thank Prof. Dr. Lorenz Korn and Prof. Dr. Birgitt Hoffmann for their enthusiasm and assistance regarding my research.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The author has received research grants from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moradi, A. Dash Kasan; an imperial architecture in the Mongol capital of Sultaniyya. asian archaeol 7, 11–27 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41826-022-00065-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41826-022-00065-x