Abstract

Depressive disorders are the most prevalent mental health disorder in adolescents with detrimental consequences; effective and available treatment is crucial. Face-to-face and computerized treatments both have advantages but also downsides. Merging these two into one so-called blended treatment seems to be an optimal combination of elements. This current review addresses blended treatment for youth depression and aims to summarize existing knowledge on effectiveness as well as patients’ and therapists’ perspectives. Results showed promising significant decreases in symptoms, but no evidence for differences between blended and face-to-face treatment was found. Patients’ perspectives were mixed; they reported strong preferences for face-to-face treatment, but participants actually receiving blended treatment were mainly positive. Therapists’ attitudes were neutral, but they expressed their worries about the unknown risks on adverse events. Future research is needed and should, beside effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, pay close attention to the risks that are mentioned by therapists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depressive disorders are the most prevalent mental health disorder in adolescents, and they are the most important cause of illness and disability (World Health Organization 2017). Youth depression has detrimental consequences; it is related to health problems, problems in interpersonal functioning, and decreased academic and professional performance (Kim-Cohen et al. 2003; Portzky and Van Heeringen 2009; Verboom et al. 2014). Furthermore, depression has a high risk on recurrence and chronicity; it is one of the most important risk factors for youth suicide (Portzky and Van Heeringen 2009), and, therefore, availability of effective treatment is crucial.

Regular face-to-face treatment for depression has shown to be effective, with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy as first choices of treatment (American Psychological Association and Guideline Development Panel for the Treatment of Depressive Disorders 2019; Weisz et al. 2005). However, average effect sizes are small to moderate, and not all individuals show improvement after receiving treatment (Klein et al. 2007; Watanabe et al. 2007; Zhou et al. 2015). But the most important reasons mentioned by youth for not seeking help are lack of time, high costs, and availability of transport (Gulliver et al. 2010). Hence, computerized treatment is often mentioned as alternative for face-to-face treatment; it ticks the boxes of being flexible, free of costs, and moreover retaining anonymity, resulting in no stigmatization and low barriers for participation (Andersson and Titov 2014; Emmelkamp et al. 2014). Most importantly, computerized treatment has proven to be effective in reducing depressive symptoms (Ebert et al. 2015) and has shown to be scalable and, therefore, can be made widely available (Titov et al. 2015). Yet, even computerized treatment, neither unguided nor guided, does not meet all preferences and needs of patients, such as personal contact and adaptability to one’s own issues. Moreover, increasing symptom severity and suicidal ideation, both common in depressed youth, are hard to detect in computerized treatment (Andersson and Titov 2014). Taken together, merging face-to-face treatment and computerized intervention into an integrated therapy, a so-called blended treatment would be the optimal combination of elements from both forms of treatment (Erbe et al. 2017; Kooistra et al. 2014; Van der Vaart et al. 2014).

Blended treatment can be defined as an integrated treatment, containing face-to-face sessions with a mental health professional combined with computerized therapy which patients follow independently (Van der Vaart et al. 2014). The computerized part of the treatment is delivered through online platforms or applications and consists of exercises, psychoeducation, and therapist feedback. This means that blended treatment serves the purpose of being flexible in location and intensity and meets the requirements of personal contact, adaptability in content, and safety in monitoring changes in severity. According to both therapists and patients, the face-to-face sessions are preferably used to getting to know one another and to prepare the use of the computerized environment (Van der Vaart et al. 2014). Further, flexibility in number and content of face-to-face sessions is suggested to meet preferences of therapists and patients.

Although blended treatment appears to be a suitable additional form of treatment as an alternative to face-to-face and computerized treatment for young people with depression, it has not yet been the subject of a review. Several reviews on Internet-based or computerized treatment have been conducted, with blended treatment excluded because of the face-to-face sessions (Ebert et al. 2015; Ye et al. 2014) or included because of the computerized part (Rasing et al. 2019a). Also, blended treatment for depressed adults has been studied in a systematic review (Erbe et al. 2017). Findings showed that blended treatment is feasible and that it is was effective compared with no intervention control conditions. It was also concluded that more research is needed to compare effectiveness to active treatment conditions.

This current review addresses blended treatment specifically for depressive disorders in youth. The main is to summarize existing knowledge of effectiveness as well as patients’ and therapists’ perspectives on blended treatment. Subsequently, it offers some suggestions regarding clinical implications and the directions of future research in this field.

Definition of Blended Treatment

As described before, blended treatment is a treatment where face-to-face sessions and a computerized treatment platform are fully integrated into one treatment protocol (Van der Vaart et al. 2014) to overcome the downsides of both face-to-face and computerized treatment (Mathiasen et al. 2016). The computerized part of blended treatment is delivered online, through a secured online platform, which can be accessed by a pc or mobile phone. Patients can independently work through several modules with psychoeducation and exercises, and therapists can deliver feedback and guidance on the platform (Erbe et al. 2017). The computerized part is combined with face-to-face sessions, which are, according to therapists and patients, preferably used for getting to know one another, establishing the therapeutic relation and preparing to use the computerized part of the program (Kenter et al. 2015; Van der Vaart et al. 2014). The sessions between therapists and patients are face-to-face with, obviously, synchronized communication, in which blended treatment differs from guided treatment where contact with therapist is often online (e.g., via chat), via phone or asynchronous. This means that blended treatment contains the benefits of both face-to-face treatment and computerized treatment. On the one hand, it holds the flexibility in location and intensity for patients, and on the other hand, it meets the requirements of personal contact, establishing a therapeutic relation, adaptability in content, and safety in monitoring changes in severity for the therapist.

Method

Search Strategy

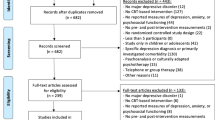

Databases Medline, PsycInfo, and Embase were systematically searched in May 2020. Search terms were (1) depression OR depressive OR depressed OR MDD OR mood disorder OR dysthymic OR dysthymia, AND (2) treatment OR therapy OR intervention OR care OR program, AND (3) blended OR blending OR blend. Using these terms, 68 studies were identified. Furthermore, twelve studies were identified through hand searching reference lists, which led to 80 identified studies. After removing duplicates, 43 studies remained. Screening of abstracts and reading the full-text articles resulted in excluding 32 studies, because these studies were about guided computerized treatment (n = 2) or focused on adult patients (n = 31). Also, two studies were excluded based on the focus of the articles (i.e., one review and one study protocol). An overview of the selection of nine studies is presented in Fig. 1.

Data Extraction

Data containing intervention effects presented as changes in depressive symptoms, feasibility, usability, acceptability, and risks of blended treatment was extracted from the studies. The data on effects was based on reports of adolescents. Other data was based on patients’ as well as therapists’ perspectives.

Results

Description of Studies

Details of the included studies are presented in Table 1. Three studies were aimed at the effects of blended treatment. Six studies were aimed at the feasibility, usability, and acceptability, based on patients’ perspectives (n = 3) or on therapists’ perspectives (n = 3). The study designs were mixed and contained randomized controlled trials (n = 3), cross-sectional studies (n = 3), a qualitative study with focus groups of therapists (n = 1), a pre-post design (n = 1), and a Delphi study (n = 1).

Changes in Depressive Symptoms

To my knowledge, only three studies have been aimed at the effectiveness of blended treatment for depressed adolescents. All studies used a randomized controlled trial design (Kobak et al. 2015; Sethi 2013; Sethi et al. 2010).

Sethi et al. (2010) performed a randomized controlled trial to compare the effects of face-to-face CBT, computerized CBT, face-to-face CBT, and computerized CBT in conjunction (i.e., blended treatment) to a control condition without treatment. Students (N = 38) aged 18 to 23 were randomized between the four conditions. Patients who received the blended treatment or face-to-face treatment showed a larger decrease in symptoms than patients who received computerized CBT. Patients in the control condition showed no symptom decrease. These findings suggest that youth with mild to moderate depressive symptoms can benefit from blended treatment as well as from face-to-face treatment.

A second study on blended CBT by Sethi (2013) randomized students aged 18 to 25 (N = 89) between four conditions, namely, face-to-face CBT, blended CBT, computerized CBT, and a control condition without treatment. Again, results showed that patients in both the face-to-face CBT condition and the blended CBT condition showed the greatest reduction in depressive symptoms, compared with patients in the computerized CBT condition who showed a significant smaller symptom decrease and patients in the control condition of whom symptoms did not decrease. The findings confirm conclusions from the previous study; mild to moderate depressed youth can benefit from blended CBT and face-to-face CBT.

In a third randomized controlled trial, Kobak et al. (2015) evaluated the effectiveness of blended CBT in treating depressed adolescents. Sixteen therapists were randomized to have their patients receive blended CBT or treatment as usual, with all therapists treating four patients. Adolescents in both treatment conditions showed significant reductions in depressive symptoms. There were, however, no significant differences in symptom decreases between treatment conditions. Therapeutic alliance was rated significantly higher in the blended CBT condition according to the therapists. This study showed that blended CBT is effective in improving symptoms of depressed adolescents.

Patients’ Perspectives

Attitudes Towards Blended Therapy

A study by Lokkerbol et al. (2018) showed that a majority of participants, who received treatment for depression in the last 12 months, did not favor computerized treatment when compared with face-to-face treatment. Blended treatment was more preferred than computerized treatment but less than face-to-face treatment. Further, findings revealed that patients with higher education were more willing to accept blended treatment but were more against computerized treatment than patients with lower education. However, using a sample of adults and young adults, with 41% aged between 18 and 25, might only reflect the attitudes of older adolescents and not necessarily of early adolescents.

When attitudes towards and satisfaction with blended treatment were studied in adolescent patients who actually received blended treatment, and their responses were based on experience, adolescents were more positive about blended treatment. Kobak et al. (2015) and De Vos et al. (2017) reported that patients were satisfied with their treatment and with the used technology. Nevertheless, half of the participants in the study by De Vos et al. (2017) attributed the decrease in symptoms to the face-to-face sessions, and one-third assumed that the decrease in symptoms was caused by the combination of the computerized treatment and the face-to-face sessions.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Blended Therapy

Adolescents considered the possibility to determine the location where they can work on the program (90%) and the time when they can work on the program (86%) as the major advantages of blended treatment (De Vos et al. 2017). Furthermore, a sample of adults and young adults reported a shorter waiting time of blended and computerized treatment as advantages, and although they preferred face-to-face treatment, they were willing to accept blended treatment if waiting time would be reduced (Lokkerbol et al. 2018).

Reasons Not to Use Blended Therapy

Often, adolescents with severe depressive symptoms are excluded from trials on computerized treatment for depression (Ebert et al. 2015), and it is, therefore, unknown whether computerized treatment is feasible for adolescents with severe depression. Therapists mostly doubt whether severely depressed adolescents can be stimulated enough to use the computerized treatment. De Vos et al. (2017) showed that patients with mild, moderate, or severe depressive symptoms did not differ in the number of characters they used in messages, the number of registrations in the mood diary, and the progress in the computerized part of the treatment.

Suggestions for Content

One study specifically reported on which modules of the blended treatment program the adolescents thought were useful and which not. Adolescents reported that they experienced the most benefit from the modules “increasing enjoyable activities,” “standing up for yourself,” “changing negative thinking,” and “good listening and self-expression.” Of these, they expected to continue using “standing up for yourself,” “increasing enjoyable activities,” and “good listening and self-expression,” together with “social skills” and “improving relationships” (De Vos et al. 2017). Additionally, adolescents reported that their impression was that they least benefitted from “concentration techniques,” of which they indicated that they had low intention to continue using it (De Vos et al. 2017).

Therapists’ Perspectives

Attitudes Towards Blended Therapy

In general, therapists’ perception of blended treatment can be described as neutral, suggesting a cautious and reserved view on this form of therapy (Schuster et al. 2018). Therapist who already used forms of computerized treatment showed a more positive attitude towards blended treatment. Other characteristics, such as age, gender, and years in profession, were not related (Schuster et al. 2018, 2020). Furthermore, therapists associate the added value to the computerized part of blended treatment, because it increases the engagement with the therapy (Cerga-Pashoja et al. 2020); they especially enhance self-management (Van der Vaart et al. 2014). Finally, therapists reveal that the motivation of therapists to use blended treatment might be equally important as technology itself in the successful implementation of blended care (Van der Vaart et al. 2014).

Advantages and Disadvantages of Blended Therapy

Therapists rated the advantages of blended therapy as average (Schuster et al. 2018). Practical benefits, such as flexibility in terms of delivering treatment, preparation in the time and pace patients prefer (Cerga-Pashoja et al. 2020; Schuster et al. 2020), and not depending on a specific treatment location (Schuster et al. 2020), are often mentioned by therapists. Additionally, the stronger engagement in the therapeutic process is mentioned as a positive effect of blended treatment (Cerga-Pashoja et al. 2020). Further, therapists experienced that blended therapy facilitates repetition and that the computerized part can be used to prepare for sessions (Cerga-Pashoja et al. 2020; Schuster et al. 2020; Van der Vaart et al. 2014).

Strikingly, therapists rated the disadvantages of blended therapy as below average and significantly lower than web-based treatment without guidance (Schuster et al. 2018). Most important disadvantages that were mentioned by therapists were risks in the therapeutic process, such as limited nonverbal signals, missing an increase in symptoms, or dealing with crisis (Schuster et al. 2018, 2020). A major disadvantage expected by therapists is the increase in workload (Schuster et al. 2018). Therapists with experience in blended therapy confirmed this expectation; they considered blended therapy as time-consuming, and it negatively impacted the amount of work (Cerga-Pashoja et al. 2020). Other disadvantages mentioned are related to the technical side of the blended programs. Difficulties in creating access, using the Internet part of the program, are ubiquitous in patients as well as therapists (Cerga-Pashoja et al. 2020). Also, some therapists think the clear format of CBT gets lost when it is combined with other forms of treatment and, therefore, and causes an information overload (Cerga-Pashoja et al. 2020).

Reasons Not to Use Blended Therapy

Therapists reported that blended therapy, in the same regards as computerized therapy, is not suitable for every patient (Van der Vaart et al. 2014). In addition, they stressed that particularly patients in secondary or specialized mental health care suffer from severe and complicated problems. They often suffer from comorbid problems beside their major depression, such as anxiety, personality problems, trauma, but also problems in social life or financial problems (Van der Vaart et al. 2014). Therapists worry that blended treatment protocols are not flexible enough to tailor treatment to their problems (Cerga-Pashoja et al. 2020; Van der Vaart et al. 2014) and that it is too difficult to register changes in symptom severity and suicidality (Schuster et al. 2018). In practical use, blended programs are perceived as more rigid to use than face-to-face treatment, which results in needing extra time. Also, therapists experienced that some patients struggled with the lower number of face-to-face sessions and presumed more sessions. This resulted in backlogs for therapists (Cerga-Pashoja et al. 2020). On top of these reasons not to use blended treatment, therapists revealed that the burden of using blended treatment protocols is higher than the advantages they experienced (Cerga-Pashoja et al. 2020; Schuster et al. 2018), and their concern to be replaced by technology (Schuster et al. 2018), which leads to not using blended therapy.

Suggestions for Content

Therapists considered face-to-face sessions crucial for therapy. They suggested that specifically the introduction between patient and therapist needs to be face-to-face. Further face-to-face sessions are essential in creating commitment, motivating patients, and, above all, monitoring changes in symptoms (Van der Vaart et al. 2014). Practical parts of treatment, such as psychoeducation and assignments, can easily be done online (Van der Vaart et al. 2014).

Discussion

This review addressed blended treatment for depressive disorders in youth, as it has not yet been the subject of a review. It aimed to summarize existing knowledge of effectiveness as well as patients’ and therapists’ perspectives on blended treatment.

To date, to my knowledge, only three studies have examined the effectiveness of blended therapy as treatment for adolescent depression. All three randomized controlled trial showed a promising significant decrease in depressive symptoms in adolescents receiving blended CBT. Moreover, all studies were not able to detect differences in symptom decrease between adolescents receiving blended CBT or face-to-face CBT. These findings are in line with a systematic review by Erbe et al. (2017), showing a significant symptom decrease in adults but also determining a lack of outcomes to identify a difference between face-to-face and blended treatment. Yet, in the current review, two of the studies established a larger symptom decrease in adolescents receiving blended or face-to-face CBT than in adolescents receiving computerized CBT or adolescents receiving no treatment (i.e., control condition), with the latter showing no decrease at all. However, these results need to be interpreted with caution, as they are based on few studies with a small number of participants.

Patients’ perspectives seem to be not consistently positive about blended treatment. In general, face-to-face treatment is preferred, followed by blended treatment and computerized treatment as least preferred. However, adolescent patients who actually received blended treatment were positive about the flexibility and about the responses of therapists (De Vos et al. 2017). Strikingly, they attributed the effect of the intervention to the face-to-face sessions. This could mean that young people initially have a preference for face-to-face treatment and, after receiving blended treatment, realize that this form of treatment also seems to suit them. A possible explanation of the finding from De Vos et al. (2017) might also be that the young people who participated in their study where predominantly adolescents who were initially not negative about blended treatment.

Therapists hold rather neutral attitudes towards blended treatment. The main issue that professionals are very critical about is the difficulty in following the progress of the treatment, especially when depressive symptoms do not improve (or even worsen) and whether suicidal thoughts, often present in depressed adolescents, develop or flare up. The same issues hold for therapist-guided computerized treatment, as shown by studies from Topooco and colleagues (Topooco et al. 2018, 2019). Not being able to properly monitor the changes and missing nonverbal signals could cause risks for these patients. Hence, therapists find it difficult to use blended treatment for, but not limited to, young people with severe depressive disorders.

Clinical Implications

The use of blended treatment as intervention for depressed adolescents heavily depends on the acceptance of this form of treatment by patients as well as by therapists. The first improvement needed is more knowledge on the effectiveness. In this review, no reason was found to assume that blended treatment is less effective than face-to-face treatment or even has no effect at all. The number of studies on effectiveness needs to be increased to reliably establish the effectiveness. Another major unknown is whether not seeing patients face-to-face actually increases the risk on adverse events, such as failing to observe increasing symptoms or suicidal ideation. It goes without saying that therapists want clarity about this before introducing blended treatment to their patients. This review showed that there is no evidence that blended treatment increases risks for depressed adolescents. Nevertheless, it needs to be mentioned that further research is imperative.

Directions for Future Research

This review underlines the importance of further research in the field of blended treatment for depressed youth. Only a limited number of randomized controlled trails aimed on the effectiveness of blended treatment were performed. Besides effectiveness, risk on adverse events needs to be taken into account. Also, the effects of blended treatment need to be compared with the effects of active treatment conditions, which the reviewed studies did. Importantly, future studies need to be done in routine care (see Rasing et al. (2019b), Mathiasen et al. (2016), and Vara et al. (2018) as examples of ongoing research in adolescents and adults). Interventions are often developed in academic settings and tested in nonclinical populations. It is unclear whether these findings can be generalized to adolescent patients in routine care.

Further, the absence of studies on cost-effectiveness revealed a vast lack in research. It is important to study cost-effectiveness of blended treatment, because it is often suggested that blended care could reduce costs in comparison with face-to-face treatment. However, findings implied that blended treatment is time-consuming for therapists and they experienced a negative impact on their workload.

Future studies on effectiveness and cost-effectiveness performed in routine care can enhance the knowledge of therapists on blended treatment and, with that, lower the threshold to use blended treatment for depressed youth.

Conclusion

To my knowledge, this is the first review of blended treatment for depressive disorders in youth, summarizing the existing knowledge and providing patients’ and patients’ perspectives. Although there are only a few studies on blended treatment, promising effects were found in symptom decrease, and no differences in effects between blended and face-to-face treatment could be established. Future research is needed and should, beside effectiveness, pay close attention to the risks that are mentioned by therapists. Without this, the use of blended treatment, which heavily depends on the acceptance by therapists, will not become a common practice.

References

American Psychological Association, & Guideline Development Panel for the Treatment of Depressive Disorders. (2019). Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of depression across three age cohorts. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/depression-guideline/guideline.pdf.

Andersson, G., & Titov, N. (2014). Advantages and limitations of Internet-based interventions for common mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 13(1), 4–11.

Cerga-Pashoja, A., Doukani, A., Gega, L., Walke, J., & Araya, R. (2020). Added value or added burden? A qualitative investigation of blending internet self-help with face-to-face cognitive behaviour therapy for depression. Psychotherapy Research, 1-13, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1720932.

De Vos, R., Tromp, N., Bodden, D., & Stikkelbroek, Y. (2017). Therapeut onmisbaar bij ‘blended therapie’tegen depressie. Kind Adolescent Praktijk, 16(2), 6–13.

Ebert, D. D., Zarski, A.-C., Christensen, H., Stikkelbroek, Y., Cuijpers, P., Berking, M., & Riper, H. (2015). Internet and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in youth: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled outcome trials. PLoS One, 10(3), e0119895. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0119895.

Emmelkamp, P. M. G., David, D., Beckers, T., Muris, P., Cuijpers, P., Lutz, W., et al. (2014). Advancing psychotherapy and evidence-based psychological interventions. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 23(S1), 58–91.

Erbe, D., Eichert, H. C., Riper, H., & Ebert, D. D. (2017). Blending face-to-face and internet-based interventions for the treatment of mental disorders in adults: systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(9), e306.

Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2010). Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 10(1), 113. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-113.

Kenter, R. M. F., Van de Ven, P. M., Cuijpers, P., Koole, G., Niamat, S., Gerrits, R. S., & Van Straten, A. (2015). Costs and effects of Internet cognitive behavioral treatment blended with face-to-face treatment: results from a naturalistic study. Internet Interventions, 2(1), 77–83.

Kim-Cohen, J., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Harrington, H., Milne, B. J., & Poulton, R. (2003). Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(7), 709–717.

Klein, J. B., Jacobs, R. H., & Reinecke, M. A. (2007). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent depression: a meta-analytic investigation of changes in effect-size estimates. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(11), 1403–1413. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e3180592aaa.

Kobak, K. A., Mundt, J. C., & Kennard, B. (2015). Integrating technology into cognitive behavior therapy for adolescent depression: a pilot study. Annals of General Psychiatry, 14(1), 37.

Kooistra, L. C., Wiersma, J. E., Ruwaard, J., van Oppen, P., Smit, F., Lokkerbol, J., et al. (2014). Blended vs. face-to-face cognitive behavioural treatment for major depression in specialized mental health care: Study protocol of a randomized controlled cost-effectiveness trial. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 290. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0290-z.

Lokkerbol, J., Geomini, A., Van Voorthuijsen, J., Van Straten, A., Tiemens, B., Smit, F., & Hiligsmann, M. (2018). A discrete-choice experiment to assess treatment modality preferences of patients with depression. Journal of Medical Economics, 22(2), 178–186.

Mathiasen, K., Andersen, T. E., Riper, H., Kleiboer, A. A. M., & Roessler, K. K. (2016). Blended CBT versus face-to-face CBT: a randomised non-inferiority trial. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 432.

Portzky, G., & Van Heeringen, C. (2009). Suïcide bij jongeren. Psychologie en Gezondheid, 37(2), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03080371.

Rasing, S. P. A., Stikkelbroek, Y. A. J., & Bodden, D. H. M. (2019a). Is digital treatment the holy grail? Literature review on computerized and blended treatment for depressive disorders in youth. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health [Electronic Resource], 17(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010153.

Rasing, S. P. A., Stikkelbroek, Y. A. J., Riper, H., Dekovic, M., Nauta, M. H., Dirksen, C. D., & Bodden, D. H. M. (2019b). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of blended cognitive behavioral therapy in clinically depressed adolescents: Protocol for a pragmatic quasi-experimental controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 8(10), e13434. https://doi.org/10.2196/13434.

Schuster, R., Pokorny, R., Berger, T., Topooco, N., & Laireiter, A.-R. (2018). Advantages and disadvantages of online and blended therapy: attitudes towards both interventions amongst licensed psychotherapists in Austria. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(12), e11007.

Schuster, R., Topooco, N., Keller, A., & Radvogin, E. (2020). Advantages and disadvantages of online and blended therapy: replication and extension of findings on psychotherapists’ appraisals. Internet Interventions. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2020.100326.

Sethi, S. (2013). Treating youth depression and anxiety: a randomised controlled trial examining the efficacy of computerised versus face-to-face cognitive behaviour therapy. Australian Psychologist, 48(4), 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12006.

Sethi, S., Campbell, A. J., & Ellis, L. A. (2010). The use of computerized self-help packages to treat adolescent depression and anxiety. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 28(3), 144–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2010.508317.

Titov, N., Dear, B. F., Staples, L. G., Bennett-Levy, J., Klein, B., Rapee, R. M., & Ritterband, L. (2015). MindSpot clinic: an accessible, efficient, and effective online treatment service for anxiety and depression. Psychiatric Services, 66(10), 1043–1050.

Topooco, N., Berg, M., Johansson, S., Liljethörn, L., Radvogin, E., Vlaescu, G., & Andersson, G. (2018). Chat- and internet-based cognitive-behavioural therapy in treatment of adolescent depression: randomised controlled trial. BJPsych Open, 4(4), 199–207. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.18.

Topooco, N., Byléhn, S., Dahlström Nysäter, E., Holmlund, J., Lindegaard, J., Johansson, S., & Andersson, G. (2019). Evaluating the efficacy of Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy blended with synchronous chat sessions to treat adolescent depression: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(11), e13393.

Van der Vaart, R., Witting, M., Riper, H., Kooistra, L., Bohlmeijer, E. T., & van Gemert-Pijnen, L. J. (2014). Blending online therapy into regular face-to-face therapy for depression: content, ratio and preconditions according to patients and therapists using a Delphi study. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 355. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0355-z.

Vara, M. D., Herrero, R., Etchemendy, E., Espinoza, M., Banos, R. M., Garcia-Palacios, A., & Botella, C. (2018). Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a blended cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in Spanish primary health care: Study protocol for a randomised non-inferiority trial. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1638-6.

Verboom, C. E., Sijtsema, J. J., Verhulst, F. C., Penninx, B. W. J. H., & Ormel, J. (2014). Longitudinal associations between depressive problems, academic performance, and social functioning in adolescent boys and girls. Developmental Psychology, 50(1), 247.

Watanabe, N., Hunot, V., Omori, I. M., Churchill, R., & Furukawa, T. A. (2007). Psychotherapy for depression among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 116(2), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01018.x.

Weisz, J. R., Doss, A. J., & Hawley, K. M. (2005). Youth psychotherapy outcome research: A review and critique of the evidence base. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 337–363.

World Health Organization. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf.

Ye, X., Bapuji, S. B., Winters, S. E., Struthers, A., Raynard, M., Metge, C., et al. (2014). Effectiveness of internet-based interventions for children, youth, and young adults with anxiety and/or depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 313.

Zhou, X., Hetrick, S. E., Cuijpers, P., Qin, B., Barth, J., Whittington, C., et al. (2015). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of psychotherapies for depression in children and adolescents: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. World Psychiatry, 14(2), 207–222.

Funding

This study was funded by the Dutch Organisation for Health research and Development (ZonMW) (grant number 70-72900-98-16144).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rasing, S.P.A. Blended Treatment for Depressive Disorders in Youth: a Narrative Review. J Cogn Ther 14, 47–58 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41811-020-00088-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41811-020-00088-1