Abstract

Background

Patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC) frequently experience fatigue, although it is often overlooked in medical research and practice.

Aims

To explore patients’ experience of fatigue and evaluate content validity, psychometric properties, and score interpretability of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue (FACIT–Fatigue) in patients with CD or UC.

Methods

Concept elicitation and cognitive interviews were conducted with participants aged ≥ 15 years with moderately-to-severely active CD (N = 30) or UC (N = 33). To evaluate psychometric properties (reliability and construct validity) and interpretation of FACIT–Fatigue scores, data from two clinical trials were analyzed [ADVANCE (CD): N = 850; U-ACHIEVE (UC): 248]. Meaningful within-person change was estimated using anchor-based methods.

Results

Almost all interview participants reported experiencing fatigue. Over 30 unique fatigue-related impacts were reported per condition. The FACIT–Fatigue was interpretable for most patients. FACIT–Fatigue items had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α 0.86–0.88 for CD and 0.94–0.96 for UC); the total score displayed acceptable test–retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficients > 0.60 for CD and > 0.90 for UC). FACIT–Fatigue scores had acceptable convergent validity with similar measures. A 7–10 point improvement for CD and 4–9 point improvement for UC on the FACIT–Fatigue total score may represent meaningful improvements.

Conclusions

These results highlight the importance of fatigue among adolescents and adults with CD or UC and provide evidence that the FACIT–Fatigue is content valid and produces reliable, valid, and interpretable scores in these populations. Care should be taken if using the questionnaire with adolescents who may be less familiar with the word “fatigue.”

Clinical trial registration numbers NCT03105128 (date of registration: 4 April 2017) and NCT02819635 (date of registration: 28 June 2016).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Fatigue is an important symptom experienced by individuals with moderately-to-severely active CD and UC, with substantial impact to their lives. |

The FACIT–Fatigue is comprehensible, relevant, and comprehensive for assessing fatigue and fatigue-related impacts for use with individuals with moderately-to-severely active CD and UC. |

FACIT–Fatigue is a reliable and valid tool that is sensitive to change, and an improvement in the FACIT–Fatigue total score of 7–10 points or 4–9 points may be clinically meaningful for patients with moderately-to-severely active CD and UC, respectively, in a clinical trial setting. |

1 Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are characterized by chronic relapsing and remitting inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. While patients with CD and UC experience similar symptoms [1,2,3], the two conditions differ with respect to the location and extent of inflammation in the GI tract. CD can affect any portion of the GI tract and presents as transmural inflammation involving all tissue layers of the bowel wall, while UC is manifested as diffuse mucosal inflammation of the colon and/or rectum [4].

One impactful, yet often overlooked, symptom of CD and UC is fatigue [4,5,6,7]. The prevalence of fatigue among CD and UC patients, based on previous literature, ranges from approximately 24% to 87% [7,8,9,10,11]. The pooled prevalence of fatigue in CD and UC was 47% based on a random-effects meta-analysis, compared with only 5% in healthy individuals. For individuals with active disease, the pooled prevalence of fatigue was 72%, compared with 47% for those in remission [7]. Common risk factors for fatigue in CD and UC include sleep disturbance, anxiety, depression, vitamin and mineral deficiencies, and anemia [7]. Fatigue is associated with impaired health-related quality of life, including high disability, decreased physical function, and negative effects on work productivity [7]. The prevalence and burden of fatigue demonstrates its importance for consideration when developing interventions for CD and UC [7].

Fatigue, however, is not conceptually straightforward—it is a multifaceted symptom that may be experienced in various ways, both within and across individuals. As such, it is important to consider an assessment approach accounting for diverse aspects of fatigue.

One common instrument to measure the patient experience of fatigue is the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue (FACIT–Fatigue), which assesses concepts related to the severity and impacts of fatigue over the past 7 days [12]. While there are many questionnaires that could be considered for the evaluation of fatigue, and even some that assess fatigue specifically among those with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ) [13], the FACIT–Fatigue captures varied fatigue-related concepts across its 13 items, allowing for a nuanced assessment (as opposed to a single item broadly evaluating fatigue).

While the FACIT–Fatigue was originally developed to assess anemia-related fatigue in cancer patients [14,15,16], and has been widely used in a variety of disease areas, the appropriateness of the FACIT–Fatigue for use in CD and UC has also been supported by prior publications [11, 17]. Previous studies on IBD have used the FACIT–Fatigue to evaluate the severity of fatigue in patients with IBD and have reported mean scores that are associated with moderate or severe fatigue [17,18,19], while lower fatigue was associated with improvements in other symptoms related to treatment [5, 20]. In addition, previous research has aimed to understand the reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change of the FACIT–Fatigue in CD and UC [17, 20,21,22].

To expand on this previous research and to confirm that the FACIT–Fatigue (13-item version) is appropriate for use in registrational clinical trials for CD and UC, the current study aimed to evaluate the content validity (readability, relevance, comprehensibility, and comprehensiveness), psychometric performance, and score interpretation of the FACIT–Fatigue for adolescents and adults with clinician-confirmed, moderately-to-severely active CD or UC.

2 Methods

2.1 Evaluation of Content Validity

Trained interviewers conducted open-ended, semi-structured qualitative interviews with adolescents and adults in the USA with moderately-to-severely active CD or UC to (1) identify, describe, and substantiate the important and relevant CD- and UC-related fatigue experiences and impacts (concept elicitation) and (2) evaluate the readability, comprehensibility, relevance, and comprehensiveness of the FACIT–Fatigue (cognitive debriefing). The study protocol and all study documents were approved by a centralized independent review board.

2.1.1 Participants

Adolescents (i.e., 15–17 years of age) and adults (i.e., ≥ 18 years of age) with a clinician-confirmed diagnosis of moderately-to-severely active CD or UC were recruited from clinical sites within the USA. The study inclusion/exclusion criteria specified, among other criteria, that Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorization, informed consent to participate for adult participants, and parental permission and assent for adolescent participants be obtained. Participants ≥ 15 years of age and ≤ 80 years old, fluent in US English, and with a clinician-confirmed diagnosis of moderate-to-severe CD or UC were considered for inclusion in the study. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in Supplementary Table 1 in the Online Resource 1: Supplementary tables and figures.

2.1.2 Conduct of Qualitative Interviews

The qualitative interviews were conducted either in person or over the phone using a semi-structured interview guide. During the interviews, participants were first asked to briefly discuss whether they have experienced fatigue related to their CD or UC and to describe how their disease-related fatigue felt and how it impacted their lives. Participants were subsequently asked to complete the FACIT–Fatigue either on an electronic device or by using screenshots of the questionnaire while “thinking aloud” about the process they used to arrive at each answer to identify any words, terms, or concepts within the questionnaire that they did not understand or did not interpret as intended. Following the “think-aloud” process, participants were asked additional questions designed to evaluate the content of the FACIT–Fatigue, including its comprehensibility, readability, relevance, and comprehensiveness. Interviews were audio recorded, following participants’ verbal consent, and subsequently transcribed and anonymized.

2.1.3 Qualitative Coding and Data Analysis

Data were analyzed separately for CD and UC. Each transcript underwent qualitative coding to organize and catalog participants’ CD- or UC-related fatigue experience, feedback, and responses on the instructions, items, and response options of the FACIT–Fatigue. All transcripts were coded in ATLAS.ti (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany); coded quotations were then further reviewed and aggregated by themes in study findings tables.

2.2 Evaluation of Psychometric Performance and Interpretability of Scores of the FACIT–Fatigue

Data from two clinical programs [risankizumab for CD Phase 3 (NCT03105128; hereafter identified as ADVANCE) [23] and upadacitinib for UC Phase 2b (NCT02819635; hereafter identified as U-ACHIEVE) [24] were used for the psychometric and score interpretation analyses. The following properties of the FACIT–Fatigue scores were evaluated for CD and UC separately: quality of completion of the questionnaire, total score distribution, reliability [internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha and test–retest reliability using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC)], and validity (convergent and discriminant validity, known-groups methods, and sensitivity to change). Further, analyses were conducted to establish meaningful within-person change (MWPC) estimates for the FACIT–Fatigue total score.

During the clinical trials, participants completed the FACIT–Fatigue questionnaire (along with other questionnaires/assessments) during clinic visits using an electronic tablet device. The methodology of these trials is described fully elsewhere [23,24,25].

2.2.1 Participants

Scores on the FACIT–Fatigue and other clinical outcome assessments (both patient reported and clinician reported) were included in the psychometric and score interpretation analyses for CD and UC separately. Analysis populations were drawn from those participants in each clinical trial who were randomized to an active treatment or placebo group, but required that participants had scores on the FACIT–Fatigue from one or more clinic visits. For CD, participants with scores on the FACIT–Fatigue at baseline, week 4, and/or week 12 of the clinical trial were included in the psychometric analyses. For UC, participants with scores on the FACIT–Fatigue at baseline, week 2, week 4, and/or week 8 were included. While all participants in the psychometric analyses were randomized, scores from all treatment groups were collapsed for all analyses (i.e., analyses did not examine the differences between treatment and placebo groups).

2.2.2 Assessments

The version of the FACIT–Fatigue (version 4) under evaluation includes 13 items measuring fatigue and its impacts. All items include the same 5-point verbal rating scale ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“very much”) with a recall period of the “past 7 days.” Items 7 (i.e., “I have energy”) and 8 (i.e., “I am able to do my usual activities”) express a positive connotation, while other items on the 5-point scale reflect a negative connotation (e.g., “I am too tired to eat”) related to fatigue. To calculate a total score, the scores of all items except for items 7 and 8 are reversed by subtracting the response from 4. After reversing the items (specifically, items 1–6 and 9–13), a total score is calculated by summing the individual item scores. The FACIT–Fatigue (version 4) has a maximum score of 52 and a minimum score of 0, where a higher score equates to less fatigue. Item numbers will be referenced as 1–13; however, the associated item bank numbers are as follows: item 1 (HI7), item 2 (HI12), item 3 (An1), item 4 (An2), item 5 (An3), item 6 (An4), item 7 (An5), item 8 (An7), item 9 (An8), item 10 (An12), item 11 (An14), item 12 (An15), and item 13 (An16).

In addition to the FACIT–Fatigue, scores of other assessments were used to support the analysis. The Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and the Crohn’s Symptoms Severity Questionnaire (CSS) were used for CD, and the Adapted Mayo Score and the Ulcerative Colitis Symptoms Questionnaire (UC-SQ) were used for UC as disease-specific assessments. Impact and quality-of-life assessments, namely the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI: CD and WPAI: UC), the IBDQ, and the 36-Item Short Form Survey Version 2 (SF-36v2®), were used for both CD and UC. The five-level EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) was used for CD/UC as a general health and utilities assessment. In addition, a disease-specific Global Impression of Change (PGIC) was used in both CD and UC, while a disease-specific Patient Global Impression of Severity (PGIS) was used for CD only. The PGIC and PGIS items asked patients to rate the change in, or the severity of, their CD or UC symptoms overall. All assessments are described in Table 1.

2.2.3 Statistical Analyses

Descriptive characteristics, reliability, validity, and score interpretation analyses were conducted on the clinical trial datasets for CD (ADVANCE) and UC (U-ACHIEVE) separately. Table 2 summarizes each set of analyses and benchmarks for determining acceptable results, where appropriate.

3 Results

3.1 Qualitative Research for Content Validity in CD and UC

3.1.1 Participant Demographics

Between January 2020 and September 2020, 30 individuals with CD and 33 individuals with UC who met all the study inclusion and none of the exclusion criteria (as described in Supplementary Table 1 in the Online Resource 1: Supplementary tables and figures) were recruited from four US clinical sites. Participants with clinician-confirmed moderate-to-severe CD (n = 20 adults and n = 10 adolescents) and UC (n = 22 adults and n = 11 adolescents) participated in qualitative hybrid concept elicitation and cognitive debriefing interviews. Participant demographic and health information are provided in Table 3.

3.1.2 Fatigue Experience

The open-ended concept elicitation portion of the interviews confirmed that almost all participants experienced fatigue due to CD or UC (CD: n = 30/30, 100.0%; UC: n = 32/33, 97.1%). Participants described fatigue as: “a feeling of physical or mental tiredness that comes in waves, exhaustion, weakness, lethargy, lack of motivation, lack of energy, wanting to go to bed or relax, sleepiness, being worn out, sluggish or slow, being unalert, lifeless, achy, and/or feeling drained.” When asked to rate fatigue on a 0–10 numeric rating scale with 0 = not bothersome at all to 10 = most bothersome, CD participants reported a mean bother rating of 6.8 [median = 7, interquartile range (IQR) = 5–8] and UC participants reported a mean bother rating of 6.2 (median = 6.5, IQR = 5–8).

Fatigue was additionally reported to impact quality of life. Participants reported fatigue-related impacts (n = 32 unique impacts for CD and n = 33 unique impacts for UC) across nine domains (activities of daily living, cognitive function, emotional function, leisure activities, physical activities, relationships, sleep, social function, and work/school). The most frequently reported CD-related fatigue impacts were lack of motivation (n = 14, 46.7%), limited social interactions (n = 11, 36.7%), difficulty starting things (n = 11, 36.7%), and limitation to household chores (n = 11, 36.7%). The most frequently reported UC-related impacts were limited physical activity (n = 18, 56.3%), limitation to household chores (n = 12, 37.5%), limited social interactions (n = 10, 30.3%), and limited productivity at work or school (n = 9, 28.1%).

3.1.3 Cognitive Debriefing of FACIT–Fatigue

During the interviews, participants completed the FACIT–Fatigue and, across items, 40.0–90.0% of participants with CD and 33.3–84.8% of participants with UC reported experiencing the assessed concepts within the recall period (Supplementary Table 2 in the Online Resource 1: Supplementary tables and figures). During the cognitive debriefing of the FACIT–Fatigue, ≥ 70.0% of CD participants and ≥ 93.0% of UC participants interpreted the instructions, recall period, items, and response options as intended, demonstrating the readability and comprehensibility of the questionnaire. The primary interpretation issue for CD was that six participants (n = 6, 20%), mostly adolescents (n = 5/6, 83.3%), reported being unfamiliar with the term “fatigue” or did not interpret the concept as intended (e.g., interpreted as nausea, dizziness, pain, sickness, or the act of taking a break/resting). Participants who did not understand the word “fatigue” were ultimately provided a definition for the purpose of understanding whether it was relevant experience. Overall, all CD and UC participants (n = 30 and n = 33, 100.0%, respectively) reported that the FACIT–Fatigue items measured concepts that are relevant to their experience, which was further supported by the spontaneous descriptions provided in the concept elicitation portion of the interviews. Participants were asked to report whether anything relevant to their fatigue experience was missing from the questionnaire, while there were multiple suggestions, the only concept mentioned by more than one person per condition was mental health/mental fatigue (reported by n = 6 with CD and n = 1 with UC)—this was described as an impact to one’s mental “state” or “mental health effects” due to fatigue which can lead to changes in one’s thinking process or mood.

3.2 CD Psychometric Evaluation and Score Interpretation

A total of 850 patients from the ADVANCE study were included in the psychometric and score interpretation analysis. Participants’ ages ranged from 16 to 79 years [mean = 37.5 years; standard deviation (SD) = 13.3 years]; slightly less than half (45.9%) of the sample was female (Table 4).

3.2.1 CD: Quality of Completion and Score Distribution

Quality of completion for the FACIT–Fatigue for the CD psychometric analysis population was high. At least 95.0% of participants had complete data across all analysis timepoints. The mean FACIT–Fatigue total score was 25.09 at baseline (n = 836, SD = 11.29), 31.07 (n = 825, SD = 11.81) at week 4, and 34.98 (n = 778, SD = 11.87) at week 12. While item 10 (too tired to eat) and item 11 (need help doing usual activities) demonstrated floor effects at baseline (> 40% of participants endorsing the lowest option, “not at all,” indicating no experience of the symptom within the recall period), improvement for these impacts was still demonstrated over time for the sample.

3.2.2 CD: Inter-item and Item-Total Correlations

Inter-item correlations using data from week 12 were moderate to strong (r = 0.32–0.90). The strongest correlation was between item 5 (trouble starting things) and item 6 (trouble finishing things) (r = 0.90 at week 12). Inter-item correlations for the ADVANCE study at week 12 are summarized in Supplementary Table 3 in the Online Resource 1: Supplementary tables and figures. For item-total correlations, the magnitude between each item in the FACIT–Fatigue scale and the FACIT–Fatigue total score across analysis timepoints ranged between r = 0.57 and r = 0.92.

3.2.3 CD: Reliability

Score reliability for the FACIT–Fatigue questionnaire was assessed in two ways: internal consistency reliability and test-retest reliability. For the first type of reliability, Cronbach’s α for the FACIT–Fatigue total score ranged from 0.86 to 0.88 from baseline to week 12, exceeding standard thresholds for acceptable internal consistency. Removal of any item did not markedly improve internal consistency reliability.

Among participants who were considered “stable” (i.e., those that either chose the same score on the PGIS for disease activity at baseline and week 4 or week 4 and week 12, or selected “no change” on the PGIC at week 4 and week 12, depending on the timepoint being evaluated), the ICCs for the FACIT–Fatigue total score ranged from 0.63 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.50–0.72] to 0.73 (95% CI, 0.64–0.79). Interpretively, the ICCs ranged from slightly below to minimally above the a priori-defined acceptable threshold of 0.70.

3.2.4 CD: Convergent and Discriminant Validity

The correlations between the FACIT–Fatigue total score and scores on almost all concurrent measures were either as strong as or stronger than expected in the correct directions, demonstrating evidence of convergent validity. Weaker correlations were hypothesized between the FACIT–Fatigue and the measures used for discriminant validity analyses (EQ-5D-5L, SF-36v2®, IBDQ, and WPAI: CD), but moderate relationships were observed, indicating fatigue is more strongly related to the constructs assessed by the discriminant measures than expected. Detailed results are presented in Table 5, summarizing the hypothesized relationships between the FACIT–Fatigue and other measures and the observed correlations between them.

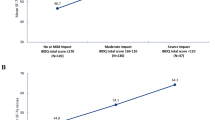

3.2.5 CD: Known-Groups Analysis

FACIT–Fatigue scores were strongly differentiated between clinically distinct groups on all measures, as expected. More specifically, FACIT–Fatigue total scores demonstrated a 10.6–11.2 point difference between groups classified as remission versus nonremission on the CDAI and a 14.9–16.6 point difference in remission versus nonremission groups using the IBDQ, and there was a monotonic decrease in the total score by PGIS group as severity improved; all comparisons were statistically significant (p < 0.001) (Table 6).

3.2.6 CD: Sensitivity to Change

Moderate-to-strong correlations were observed (0.430–0.701) between the FACIT–Fatigue change score and change scores on concurrent measures from baseline to week 12, except for the EQ-5D-5L mobility and self-care domains and the WPAI: CD work-time-missed domain. These three domains were weakly correlated with the FACIT–Fatigue change score (0.287, 0.236, and 0.269, respectively). Stronger correlations were observed between FACIT–Fatigue change scores and conceptually similar measures such as the SF-36v2 Physical Component Summary and IBDQ item 2 (0.624, 0.658, and 0.701, respectively).

3.2.7 CD: Interpretation of Scores—Anchor-Based Methods and Supportive Analyses

For CD, FACIT–Fatigue total score improved in parallel with each PGIS and PGIC anchor level. One and two point improvements on the PGIS generated a total score change of 6.17–10.03 on the FACIT–Fatigue (Table 7). Anchor groups on the PGIC (“minimally improved” or “much improved”) generated a 6.83–13.63 point improvement in FACIT–Fatigue total score (Table 8).

Considering additional evidence from empirical cumulative distribution function (eCDF) curves and probability distribution function (PDF) curves, it is reasonable to conclude that a change on the FACIT–Fatigue of 7–10 points may indicate meaningful improvement (i.e., an estimate of MWPC). Based on receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, a 9 point change in the total score is recommended as a threshold for determining meaningful improvement (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Figs. 1–3 in the Online Resource 1: Supplementary tables and figures).

3.3 UC Psychometric Evaluation and Score Interpretation

A total of 248 patients from the U-ACHIEVE study were included in the psychometric analysis. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 75 years (mean = 42.3 years, SD = 14.1 years); 60% of the sample was female (Table 4).

3.3.1 UC: Quality of Completion and Score Distribution

Quality of completion for the UC psychometric analysis population was high. At least 92.6% of the population had complete data across analysis timepoints. The mean FACIT–Fatigue total score was 28.7 at baseline (n = 238, SD = 11.7) and 38.4 (n = 214, SD = 11.4) at week 8.

In general, respondents used the entire range of the response scale for the FACIT–Fatigue items across assessment timepoints, and scores trended toward improvement over time.

3.3.2 UC: Inter-item and Item-Total Correlations

Week 8 correlations between FACIT–Fatigue items were moderate to strong in magnitude (from 0.49 to 0.94). Similar to the CD results, the highest correlations were between items 5 (trouble starting things) and 6 (trouble finishing things) for all timepoints. The lowest correlations were between items 8 (usual activities) and 9 (sleep during the day), which were negatively correlated due to the reverse score direction of the items. Item-total correlations across analysis timepoints ranged between 0.52 and 0.86, exceeding the threshold for acceptable item-total correlations of ≥ 0.3 [26].

3.3.3 UC: Reliability

Overall, Cronbach’s α ranged from 0.94 to 0.96 from baseline to week 8, exceeding the standard thresholds for acceptable internal consistency. Removing items for the UC dataset did not improve the α coefficient at any of the timepoints.

Among participants who (1) selected “no change” on the PGIC at week 2 or (2) selected the same response at both baseline and week 2 on UC-SQ item 6 (tired, lacking energy during the past week), the FACIT–Fatigue total showed adequate test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.908 and ICC = 0.945 for PGIC and UC-SQ item 6 definitions of stability, respectively). All items demonstrated acceptable test–retest reliability for one or both stability definitions.

3.3.4 UC: Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Among the UC population, the correlations between the FACIT–Fatigue total score and scores on almost all concurrent measures were either as strong as or stronger than expected in the correct directions, demonstrating evidence of convergent validity. Exceptions were the self-care domain of the EQ-5D-5L and the Adapted Mayo Score, which had weaker than expected correlation with the FACIT–Fatigue total score in the UC sample. Weak correlations were hypothesized between the FACIT–Fatigue and the measures used for discriminant validity analyses (EQ-5D-5L, SF-36v2®, IBDQ, and WPAI: UC), but moderate relationships were observed, indicating fatigue is more strongly related to the constructs assessed by the discriminant measures than expected. Detailed results are presented in Table 9, summarizing the hypothesized relationships between the FACIT–Fatigue and other measures, and the observed correlations between them.

3.3.5 UC: Known-Groups Analysis

FACIT–Fatigue total scores demonstrated a 0.9–3.6 point difference between groups classified as remission versus nonremission on the Adapted Mayo Score, which was not statistically significant at week 2 but was statistically significant at week 8 (Table 10).

3.3.6 UC: Sensitivity to Change

Moderate-to-strong correlations were observed (0.45–0.76) between the FACIT–Fatigue change score and change scores on concurrent measures, except for the EQ-5D-5L mobility domain, EQ-5D-5L self-care domain, and WPAI:UC work-time-missed domains. These were weakly correlated with the FACIT–Fatigue change score (0.20, 0.20, and 0.35, respectively). Stronger correlations were observed between FACIT–Fatigue change scores and conceptually similar measures such as the SF-36v2 Physical Component Summary and IBDQ Total Score (0.61 and 0.76, respectively).

3.3.7 UC: Interpretation of Scores—Anchor-Based Methods and Supportive Analyses

The FACIT–Fatigue total score improved in parallel with each PGIC anchor level. Anchor groups on the PGIC (“minimally improved” or “much improved”) generated a total score change of 4.24–9.33 points for phase 2b U-ACHIEVE substudy 1 (Table 11).

Considering all additional evidence (results for eCDF, PDF, and ROC curves are in Online Resource 1: Supplementary tables and figures), a change on the FACIT–Fatigue between 4 and 9 points can be recommended as meaningful improvement thresholds (i.e., an estimate of MWPC). Results are presented in Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Figs. 4–6 in the Online Resource 1: Supplementary tables and figures.

4 Discussion/limitations

This study demonstrated the importance and relevance of fatigue among IBD patients as well as the validity of the FACIT–Fatigue in measuring fatigue in moderate-to-severe IBD. To the knowledge of the authors, these were the first studies to thoroughly evaluate the content validity of the FACIT–Fatigue among adolescent and adult patients with moderately-to-severely active CD and UC separately. Results from the qualitative study provide details on the experience of fatigue and evidence supporting the use of the FACIT–Fatigue in these populations.

Specifically, during concept elicitation and cognitive debriefing interviews, all but one participant [i.e., over 98% of participants (n = 62/63)] reported experiencing fatigue. Participants reported cognitive, physical, social, work/school, sleep, leisure, emotional, and relationship impacts, as well as impacts to activities of daily living due to fatigue. Patients rated fatigue above a 6.0 on a scale from 0 (not at all bothersome) to 10 (most bothersome). In general, patients interpreted the FACIT–Fatigue content as intended and reported the questionnaire was relevant and comprehensive. However, a subset of CD patients (n = 6/63, 9.5%, mostly adolescents) reported being unfamiliar with the term “fatigue” (although upon receiving clarification, all of them reported experiencing it). This result poses a limitation to the content validity of the questionnaire for use with adolescents. Researchers may consider providing a definition of fatigue when administering the FACIT–Fatigue, especially within adolescent populations. If individuals are not provided with a definition of the term, there is risk that they may not be responding about the intended concept. This study was limited in sample size and greater research may be needed to better understand the extent of adolescent understanding of fatigue and whether it may vary between CD and UC.

Further, analyses using two clinical trial datasets demonstrated that the scores on the FACIT–Fatigue had (1) good internal consistency and acceptable test–retest reliability and (2) acceptable convergent and discriminant validity, known-groups results, and sensitivity to change. These results aligned with findings from Tinsley et al. [17] where the reliability and validity of the FACIT–Fatigue was evaluated among adults with CD or UC. While floor effects were observed for items 10 and 11 among CD patients at baseline, improvements in item-level scores still occurred over time. It may be that the floor effects observed at baseline do not indicate restriction in the FACIT–Fatigue response scale but likely reflect participants’ actual levels of fatigue-related impact. Overall, although the FACIT–Fatigue was not developed for use in IBD, results from this research provide evidence that fatigue is relevant and highly important to CD and UC patients and that the FACIT–Fatigue has sound psychometric properties in this patient population.

This study was also the first to summarize thresholds for MWPC for the FACIT–Fatigue total score for patients with moderately-to-severely active CD or UC and provides guides for interpreting within-patient score changes in this population. A variety of quantitative methods were employed to generate reliable estimates, and during the qualitative interviews, patients described meaningful changes in fatigue, which provided context to aid in the interpretation of quantitative MWPC estimates. MWPC estimates differed by condition, and the threshold was higher for the analyses of the CD clinical trial data compared with the UC data (7–10 point improvement for CD and 4–9 point improvement for UC). This aligns with the qualitative results; the degree of bother of fatigue was generally higher among CD patients than UC patients, which may explain such differences. The ranges of MWPC estimates for the FACIT–Fatigue can be used as a guide for future clinical research for each condition, but it should be noted that if the target patient population or other trial characteristics (e.g., number of study weeks, administration schedule) differs, MWPC estimates may be impacted as well. Therefore, these ranges are presented to a starting place or aid in developing endpoints based on the FACIT–Fatigue scores for future research in CD and UC. After triangulating all evidence including ROC and eCDF graphs, an improvement of 9 and 5 points on the FACIT–Fatigue for CD and UC, respectively, could be considered for future clinical research in these target patient populations. These MWPC estimates were applied in the ADVANCE and phase 3 U-ACHIEVE trials, which demonstrated significantly greater portions of patients in treatment groups versus placebo were responders [27,28,29,30].

Data for psychometric evaluation of the FACIT–Fatigue came from two randomized clinical trials. The sample sizes for psychometric analyses were large, and data were of high quality. Patients had little missing data on the FACIT–Fatigue across timepoints, and data were captured in a standardized way during the trials.

While relying on data from clinical trials provided large samples of quality data, the test–retest analysis populations were limited because, due to the nature of clinical research, there were challenges to identifying a subgroup of “stable” patients (i.e., patients with unchanging disease status) across timepoints to include in analyses primarily due to the long duration between assessment timepoints and the administration of treatment. ICCs for CD ranged from slightly below to minimally above the threshold for acceptability. Given constraints in the available data, the ICCs for CD and UC should be interpreted with caution, as they likely underestimate the reliability of the scores. Using a fatigue-specific anchor (UC-SQ item 6) to identify stable patients in UC yielded higher ICCs. Additional research should evaluate the test–retest reliability of the FACIT–Fatigue in CD and UC patients using a larger sample of stable patients and define stability specific to fatigue.

Additional paths forward for future research may include comparing the FACIT–Fatigue with other multi-item fatigue scales, evaluating the FACIT–Fatigue among individuals with mild disease, and evaluating the differences in how fatigue impacts quality of life between CD and UC.

5 Conclusions

This study demonstrated the relevance and importance of fatigue to patients’ disease experience in moderately-to-severely active CD and UC. Cognitive debriefing results provided evidence that the FACIT–Fatigue can be interpreted as intended and has comprehensive coverage of fatigue and fatigue-related impacts among adults with moderately-to-severely active CD or UC; however, some caution may be needed when using this questionnaire with adolescents who may have difficulty understanding the word “fatigue.” Psychometric analyses indicate that the scores generated by the FACIT–Fatigue demonstrate acceptable reliability, construct validity, and sensitivity to change. Further, a 7–10 point improvement for CD and a 4–9 point improvement for UC on the FACIT–Fatigue total score may represent meaningful improvements and may serve as context for future research in individuals with moderate-to-severe CD and UC.

References

Danese S, Fiocchi C. Ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(18):1713–25.

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Ulcerative Colitis. 09/2014; https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/ulcerative-colitis. Accessed 29 Mar 2022.

Panaccione R. Mechanisms of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;9(8):529–32.

Gohil K, Carramusa B. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. P T. 2014;39(8):576–7.

Villoria A, García V, Dosal A, et al. Fatigue in out-patients with inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and predictive factors. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7): e0181435.

Klusmann B, Fleer J, Trovote KA, et al. Trajectories of fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(12):1919–30.

D’Silva A, Fox DE, Nasser Y, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for fatigue in adults with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(5):994–1009.

Bager P, Befrits R, Wikman O, et al. Fatigue in out-patients with inflammatory bowel disease is common and multifactorial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(1):133–41.

Borren NZ, van der Woude CJ, Ananthakrishnan AN. Fatigue in IBD: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(4):247–59.

Jelsness-Jørgensen LP, Bernklev T, Henriksen M, Torp R, Moum BA. Chronic fatigue is more prevalent in patients with inflammatory bowel disease than in healthy controls. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(7):1564–72.

Nocerino A, Nguyen A, Agrawal M, Mone A, Lakhani K, Swaminath A. Fatigue in inflammatory bowel diseases: etiologies and management. Adv Ther. 2020;37(1):97–112.

FACIT Fatigue Scale (Version 4). 1997; http://www.ser.es/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/FACIT-F_INDICE.pdf. Accessed 29 Mar 2022.

Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine EJ, et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96(3):804–10.

Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(2):63–74.

Meysami A, Yari H, Haghighat S, Montazeri A. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-Fatigue Subscale): validity and reliability of the Iranian version. Oncol Res Treat. 2017;40(12):789–93.

FACIT.org. FACIT-F: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue. https://www.facit.org/measures/FACIT-F. Accessed 29 Mar 2022.

Tinsley A, Macklin EA, Korzenik JR, Sands BE. Validation of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue (FACIT-F) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. AlimentPharmacol Ther. 2011;34(11–12):1328–36.

Conley S, Proctor DD, Jeon S, Sandler RS, Redeker NS. Symptom clusters in adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Res Nurs Health. 2017;40(5):424–34.

Williet N, Sarter H, Gower-Rousseau C, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in a French Nationwide Survey of inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(2):165–74.

Loftus EV, Feagan BG, Colombel JF, et al. Effects of adalimumab maintenance therapy on health-related quality of life of patients with Crohn’s disease: patient-reported outcomes of the CHARM trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(12):3132–41.

Farrell D, Artom M, Czuber-Dochan W, Jelsness-Jørgensen LP, Norton C, Savage E. Interventions for fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4(4):Cd012005.

Saraiva S, Cortez-Pinto J, Barosa R, et al. Evaluation of fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease—a useful tool in daily practice. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(4):465–70.

D’Haens G, Panaccione R, Baert F, et al. Risankizumab as induction therapy for Crohn’s disease: results from the phase 3 ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2015–30.

Sandborn WJ, Ghosh S, Panes J, et al. Efficacy of upadacitinib in a randomized trial of patients with active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(8):2139-2149.e2114.

Ghosh S, Sanchez Gonzalez Y, Zhou W, et al. Upadacitinib treatment improves symptoms of bowel urgency and abdominal pain, and correlates with quality of life improvements in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2021;15:2022.

Thompson B, Vacha-Haase T. Psychometrics is datametrics: the test is not reliable. Educ Psychol Measur. 2000;60(2):174–95.

Danese S, Tran J, D’Haens G, et al. OP08 The effects of maintenance therapy with upadacitinib on abdominal pain, bowel urgency, and fatigue in patients with moderately to severely active Ulcerative Colitis: Phase 3 U-ACHIEVE maintenance results. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2022;16(Supplement_1):i008-i010.

Danese S, D’Haens G, Rubin D, et al. Patients with ulcerative colitis report improvements in abdominal pain, bowel urgency, and fatigue with 8-week upadacitinib treatment in two phase 3 trials: U-ACHIEVE and U-ACCOMPLISH. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2021;9(S8):25.

Peyrin-Biroulet L, Louis E, Ghosh S, et al. DOP88 Effect of risankizumab on patient-reported outcomes in patients with Crohn’s Disease who had an inadequate response or intolerance to conventional and/or biologic treatments: Results from phase 3 MOTIVATE and ADVANCE trials. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2021;15(1):S119–21.

Peyrin-Biroulet L, Ghosh S, Lee SD, et al. Effect of risankizumab on health-related quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease: results from phase 3 MOTIVATE, ADVANCE and FORTIFY clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023;57(5):496–508.

Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, Kern F Jr. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70(3):439–44.

Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(26):1625–9.

Reilly MC, Gerlier L, Brabant Y, Brown M. Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire in Crohn’s disease. Clin Ther. 2008;30(2):393–404.

Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–65.

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83.

Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen M, Kind P, Parkin D. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–36.

Wang L, Zhang Z, McArdle JJ, Salthouse TA. Investigating ceiling effects in longitudinal data analysis. Multivar Behav Res. 2009;43(3):476–96.

Hinkle DE, Jurs SG, Wiersma W. Applied statistics for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1988.

Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297–334.

Bland JM, Altman DG. Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ. 1997;314(7080):572.

Weir J. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19(1):231–40.

Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41(5):582–92.

Basson M. How is ulcerative colitis (UC) defined based on the extent of disease? https://www.medscape.com/answers/183084-13754/how-is-ulcerative-colitis-uc-defined-based-on-the-extent-of-disease. Accessed 29 Mar 2022.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Alan Shields, Roger Lamoureux, Emma Pranschke, Ryan Hoffman, Naomi Suminski, Doug Huntington, Jeff Mcdonald, and Alejandro Moreno-Koehler for their important contributions to the completion of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authorship statement

EVL is acting as the submission's guarantor. AbbVie and Adelphi Values authors collaborated on the conception of the study design, conduct of research, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. All authors had access to the data results and participated in the development, review, and approval of this manuscript. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship. All authors have approved the final version of the article, including the authorship list.

Declaration of personal interests

Edward Loftus has received financial support for research from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Genentech, Gilead, Gossamer Bio, Janssen, Pfizer, Receptos, Robarts Clinical Trials, Takeda, Theravance, and UCB; and received consultancy fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Arena, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Calibr, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Fresenius Kabi, Genentech, Gilead, Gossamer Bio, Iterative Scopes, Janssen, Morphic, Ono Pharma, Pfizer, Protagonist, Scipher Medicine, Sun Pharma, Surrozen, Takeda, and UCB. Ashwin Ananthakrishnan has received funding from the US National Institutes of Health, served on scientific advisory boards for Gilead and received research funding from Pfizer. Wan-Ju Lee, Yuri Sanchez Gonzalez, Kristina Fitzgerald, Kori Wallace, and Wen Zhou are full-time employees of AbbVie and may hold AbbVie stock and/or stock options. Leighann Litcher-Kelly, Sarah Ollis, and Sylvia Su are employed by Adelphi Values LLC, which received payment from AbbVie Inc. to support the research activities presented in this publication. Silvio Danese has received consultancy fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Celltrion, Ferring, Gilead, Hospira, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, MSD, Mundipharma, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, Takeda, TiGenix, UCB, and Vifor Pharma. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship.

Declaration of funding interests

This work was supported by AbbVie, Inc. AbbVie participated in the study design, research, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing, reviewing, and approving the publication. Writing support was provided by Naomi Suminski and Emma Pranschke of Adelphi Values and funded by AbbVie, Inc.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this research may be available from AbbVie, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current research, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of AbbVie.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for the interview study was obtained via a centralized independent review board. Ethical approval for the clinical trials was obtained separately.

Consent to participate

All interview and clinical trial participants provided consent (or assent with parental/guardian consent, as appropriate).

Consent for publication (from patients/participants)

Not applicable.

Code availability

May be available upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Loftus, E.V., Ananthakrishnan, A.N., Lee, WJ. et al. Content Validity and Psychometric Evaluation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue (FACIT–Fatigue) in Patients with Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. PharmacoEconomics Open 7, 823–840 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-023-00419-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-023-00419-w