Abstract

Objective

Point-of-care testing (POCT) has become an essential diagnostic technology for optimal patient care. Its implementation, however, still falls behind. This paper reviews the available evidence on the health economic impact of introducing POCT to assess if poor POCT uptake may be related to lacking evidence.

Study Design

The Scopus and PubMed databases were searched to identify publications describing a health economic evaluation of a point-of-care (POC) test. Data were extracted from the included publications, including general and methodological characteristics as well as the study results summarized in either cost, effects or an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. Results were sorted into six groups according to the POC test’s purpose (diagnosis, screening or monitoring) and care setting (primary care or secondary care). The reporting quality of the publications was determined using the CHEERS checklist.

Results

The initial search resulted in 396 publications, of which 44 met the inclusion criteria. Most of the evaluations were performed in a primary care setting (n = 31; 70.5%) compared with a secondary care setting (n = 13; 29.5%). About two thirds of the evaluations were on POC tests implemented with a diagnostic purpose (n = 28; 63.6%). More than 75% of evaluations concluded that POCT is recommended for implementation, although in some cases only under specific circumstances and conditions. Compliance with the CHEERS checklist items ranged from 20.8% to 100%, with an average reporting quality of 72.0%.

Conclusion

There were very few evaluations in this review that advised against the implementation of POCT. However, the uptake of POCT in many countries remains low. Even though the evaluations included in this review did not always include the full long-term benefits of POCT, it is clear that health economic evidence across a few dimensions of value already indicate the benefits of POCT. This suggests that the lack of evidence on POCT is not the primary barrier to its implementation and that the low uptake of these tests in clinical practice is due to (a combination of) other barriers. In this context, aspects around organization of care, support of clinicians and quality management may be crucial in the widespread implementation of POCT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Very few evaluations recommend against the implementation of POCT. |

POCT is proven to be a valuable counterpart to traditional laboratory testing |

The lack of evidence on POCT does not appear to be the primary barrier to its implementation |

1 Introduction

Diagnostic testing plays a pivotal part in guiding disease management to improve patient outcomes and wellbeing. Accurate diagnostics can result in both clinical benefits for patients and economic benefits for the healthcare system [1]. Patient outcomes can be improved significantly with diagnostic testing when it is used to identify those patients that will benefit the most from downstream actions, such as initiating, modifying, stopping, or withholding treatment [2]. Furthermore, it can also help to decrease the related healthcare costs by directing resources and care to those that will benefit the most [1].

Early detection of diseases is often cited as being of crucial importance for a patient’s survival and to reduce the risk of serious complications [3,4,5]. To benefit from earlier detection, the diagnostic and therapeutic processes need to be accelerated [6,7,8,9]. One way to do this is with the use of point-of-care testing (POCT), a test that supports clinical decision making, which can be performed nearby the patient. It is typically performed during or very close to the time of consultation with results available in minutes [10]. When appropriately utilized, POCT can improve healthcare delivery by providing test results more rapidly, allowing treatment decisions to be made earlier, and eliminates the need for individuals to transfer to another location for (laboratory) testing.

Point-of-care testing (POCT) has been proven to be beneficial for different applications (monitoring, screening, diagnosis) in several settings. In primary care, GPs can make medical decisions almost immediately, without having to wait for test results from a laboratory [11]. It also makes monitoring patients easier, allowing GPs to change medication on the spot [12]. In countries where the distance to and between medical facilities are quite large, POCT can prevent delay and discomfort. In secondary care, POCT has resulted in shorter waiting time for results, earlier discharge, and a decreased length of stay, which is especially useful in hospitals running over capacity [13]. In low-resource countries with poor infrastructure, the low cost, ease of use, and swiftness of POCT has been especially beneficial to allow diagnosis, screening, and monitoring of infectious diseases, since access to hospitals and laboraties are limited [14]. Furthermore, it has also been showed that patient satisfaction increases when POCT is used [15].

There are a wide variety of point-of-care (POC) tests available for the diagnosis, screening, and monitoring of several diseases and health problems, such as cardiovascular disease, sexually transmitted diseases, venous thromboembolism, diabetes mellitus, and respiratory‐tract infections [16]. The uptake of different POC tests can vary across devices and diseases areas. Variation in uptake can be explained by several factors, such as the number of eligible patients, the perceived clinical utility or the pricing as well as organizational aspects [17]. POC tests may, in some cases, be relatively expensive compared with central laboratory testing. Even for POC tests with proven acceptable accuracy and effectiveness, concerns remain about the cost effectiveness of the tests. One of the first systematic reviews on POCT in primary care [18] reported on the lack of economic analyses on POCT and claimed conclusions about its cost effectiveness could not be drawn due to “insufficient data”. Almost a decade later, the National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry published another systematic review of POCT [19], and again, it was reported that there was a lack of reliable evidence regarding the cost effectiveness of POC tests. This lack of evidence may limit support of policy makers regarding implementation strategies for POCT.

This paper presents a systematic review on the available evidence on the health economic impact of introducing POCT and thereby updates previous research in this area [18, 19].

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Search Strategy

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed while carrying out this systematic review [20]. The review aimed to identify publications that evaluated the use of POCT compared with traditional methods (i.e., where no POC tests are used) in terms of health economic outcomes. The publication had to describe any of the following health economic analyses [21]: cost minimization, cost effectiveness, cost consequence, cost utility, cost benefit, budget impact. The study could include any population, time horizon, and perspective and could be based on real-world data, trial data, experimental data, or simulation modeling.

Scopus and PubMed was searched for relevant publications in the English or Dutch language, between 2007 and 2019. The search was performed in December 2019 and included all terms and text words related to the intervention (POCT) and the type of analysis (health economic evaluations). To ensure that a wide-ranging set of relevant publications were included in the search, the selected search query was kept broad. The review protocol for this systematic review is illustrated in the electronic supplementary material (ESM) as a series of steps that were followed.

The search protocol used (in Scopus format) was:

(TITLE (“POCT” OR “Point of care” OR “Point of care testing” OR “rapid testing” OR “bedside testing” OR “laboratory-independent” OR “near patient testing”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Health effect*” OR “Economic effect*” OR “health economic” OR “cost minimization” OR “cost-effectiveness” OR “cost consequence” OR “cost-utility” OR “cost-benefit” OR “budget impact”)) AND PUBYEAR > 2006

Publications were included based on the following criteria:

-

Patients: any human patient population.

-

Intervention: an existing POC test that is used to diagnose, screen, or monitor disease. Hypothetical (non-existent) POC tests were excluded.

-

Comparator: the publication should compare the usage or implementation of POCT with one or more strategies, not including POCT. For example, if a publication compared different POCT guidelines without also comparing these to a strategy that did not including POCT, it was excluded from further analysis.

-

Study design: publications had to compare POCT with non-POCT (e.g., laboratory testing) in terms of health and/or cost outcomes. The publication had to describe a health economic evaluation, and report on its methods, data, and results. The evaluation could either be a trial-based or model-based cost-minimization analysis (CMA), cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), cost-consequence analysis (CCA), cost-utility analysis (CUA), cost-benefit analysis (CBA), or budget impact analysis (BIA). Publications not mentioning or performing such analyses but still investigating economic and/or health aspects and comparing POCT with an alternative without POCT, were also included (if they met the other criteria). Editorials, letters, methodological/protocol articles, and reviews were excluded.

-

Setting: the intervention could be evaluated in any country, as long as it was applied in a primary care or secondary care setting. Publications describing a POC test evaluation in an at-home or self-monitoring setting were excluded.

2.2 Study Selection

After collecting publications from Scopus, the titles and abstracts of identified studies were screened for relevance by one reviewer (DL) and discussed with a second reviewer (HK) when required. Any disagreements during the screening were resolved through discussion with a third and fourth reviewer (MIJ, RK).

If there was any doubt whether or not a publication met the criteria based on the abstract, it was included for full-text assessment. The full-text assessment of all included publications was performed by one reviewer (DL).

2.3 Data Extraction and Management

The data was extracted manually by one reviewer (DL) from the publications into Microsoft Excel (version 2016) in pre-defined and labeled columns. General publication characteristics that were extracted, consisted of the country where the evaluation was performed, how the POCT was applied (disease and purpose), whether the POC test was evaluated in a primary care or secondary care setting, the specific setting (e.g., hospital or general practice), the purpose of the POC test (diagnosis, monitoring, or screening), the comparator, and the population. Furthermore, some methodological characteristics were also extracted, namely whether the evaluation was model- or trial-based, the type of health economic evaluation performed, the chosen time horizon, the perspective from which the costs and effects were evaluated, and the type of sensitivity analysis. Outcomes of interest extracted were the impact of POCT on costs (overall costs and cost per patient), the impact on health outcomes (e.g., quality-adjusted life-years [QALYs]/disability-adjusted life-years [DALYs], prescriptions avoided, life-years saved), and the balance between the two (e.g., incremental cost-effectiveness ratio). The conclusions of each evaluation were also extracted. The extracted data was summarized in both text and table format before providing a descriptive synthesis of findings.

2.4 Methodological Assessment

The reporting quality of the publications included in the synthesis set was determined by assessing how many of the 24 key criteria contained in the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) checklist were met [22]. This checklist was selected based on its endorsement by several journals as a guideline on how to report a health economic evaluation. The 24 criteria items are divided according to title and abstract (2 items); introduction (1 item); methods (14 items); results (4 items), and discussion (3 items). When scoring publications against the CHEERS checklist, items that completely met the criteria were given a score of 1, while a score of 0 was given to items that did not meet the criteria. If an item only partially met the criteria, it was also given a score of 0. In individual studies, some of the criteria items were deemed as not applicable. For example, if the evaluation was performed alongside a trial without the use of a model, aspects such as choice of model (item 15), and assumptions underlying the model (item 16), were not applicable. Furthermore, if the evaluation was a cost analysis only, the measure of effectiveness (item 11) was not applicable. Therefore, only criteria items relevant to the publication counted towards the calculation of its overall compliance. To assess the overall compliance of a publication with the checklist, the proportion of criteria items that were met were calculated, based on a total number of applicable criteria items in the checklist. If > 75% of the criteria items were met, publications were classified as high quality; if between 50% and 75% of the items were met, they were classified as medium quality; and if < 50% of the items were met, they were classified as low quality.

The reporting quality did not play any role in the inclusion or exclusion of publications; all publications meeting the inclusion criteria had their quality assessed as described above.

3 Results

3.1 Search Results

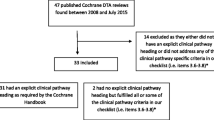

A total of 540 publications were obtained from the initial search of the Scopus and PubMed database, of which 144 were duplicates. A further 300 publications were excluded during the abstract screening. The main reason for excluding publications was because they did not describe a health economic evaluation or did not compare with non-POCT. After screening all abstracts, 96 publications were included in the full-text assessment. Based on the full-text assessment, 52 publications were excluded, with the main reasons for exclusion that publications did not describe a health economic evaluation (n = 21) or did describe a comparison of POCT with a method that did not include POCT (n = 18). Ultimately, 44 publications were included in the final review for synthesis. The PRISMA flow diagram of the search is presented in Fig. 1.

3.2 General Characteristics

An overview of the general characteristics of the publications that were included for synthesis is provided in Table 1. Publications with a score of > 75%, based on the CHEERS checklist, are shaded green. Nearly 60% (n = 26) of the 44 publications were published since 2015, with countries of origin being the United States (n = 9) and the United Kingdom (n = 7), followed by the Netherlands (n = 5) and Australia (n = 4). There were also several publications focusing on Sub-Saharan Africa (n = 10), of which four were specific to South Africa and two to Mozambique.

Most of the evaluations were described in a primary care setting (n = 31; 70.5%) compared with a secondary care setting (n = 13; 29.5%). More than half of the evaluations were on POC tests implemented with a diagnostic purpose (n = 28; 63.6%), whereas the number of evaluations on monitoring (n = 7; 15.9%) and screening tests (n = 7; 15.9%) were evenly divided. In one publication, the POC test being evaluated was implemented for both monitoring and screening purposes, whereas in another, the test was implemented with both a diagnostic and monitoring purpose.

The POC tests being evaluated cover several health problems. Some publications evaluated a POC test for more than one health problem, resulting in a total of 57 entries. Among these, acute coronary syndrome and cardiovascular diseases were the most covered diseases (n = 9), followed by respiratory infections (n = 6), HIV/Aids (n = 6), sexually transmitted diseases (n = 5) including chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis, diabetes (n = 4), and anticoagulant therapy and hemostasis (n = 4).

Overall, a total of 61 effectiveness measures were reported across all publications. The measure of effectiveness that was reported on the most was QALYs (n = 12), followed by antibiotic prescriptions (n = 6), length of stay (n = 5), life expectancy (n = 5), and hospitalization/referrals (n = 4). The length of stay measure (n = 5) was unique to evaluations in a secondary care setting, and measures related to antibiotic prescriptions (n = 6) were only used in evaluations in primary care.

3.3 Health Economic Evaluations of Point-of-Care Testing (POCT)

3.3.1 Screening

The outcomes for POC tests that were evaluated in the screening of patients are summarized in Table 1 in the ESM. This category has the lowest number of publications (n = 8), with six publications in a primary care context and two publications in a secondary care context, each with one evaluation. Only three of the evaluations reported a ratio of the costs and effectiveness. In all of these evaluations, POCT resulted in favorable cost effectiveness compared with usual care and the implementation of POCT is recommended. Of the remaining five evaluations not reporting a ratio, four found that POCT is less expensive and increases effectiveness while one reported an increase in both costs and effectiveness. All but one of these evaluations concluded that the implementation of POCT is a cost-effective option. Owusu-Edusei et al. concluded in their evaluation of primary care syphilis screening in Sub-Saharan Africa, that some POC tests could lead to overtreatment and would generally only be cost-effective in resource-poor settings with high disease prevalence [23].

3.3.2 Diagnostics

A summary of the outcomes for POC tests that were evaluated as a diagnostic (or for diagnostic support) is provided in Table 2 in the ESM. About two-thirds of the publications in this review evaluated POCT as a diagnostic (or for diagnostic support). Twenty-three of the 34 evaluations reported a ratio of the costs and effectiveness. Of these, 20 concluded in favor of implementing POCT, while one concluded against its implementation based on a high probability that POCT is dominated by standard care. One evaluation noted that the ratio changes according to adherence to clinical guidelines and concluded that POCT becomes considerably less cost effective when deviating from clinical guidelines; that is, when the test outcome does not always affect the subsequent patient management decision. Of the 11 evaluations that did not report a ratio, all found an increase in effectiveness due to POCT, two found an increase in costs, while the rest reported cost savings.

3.3.3 Monitoring

A summary of the outcomes for POC tests that were evaluated for the monitoring of patients is provided in Table 3 in the ESM. In total, ten evaluations considered a primary care context and four evaluations a secondary care context. Nine of the evaluations reported a ratio of the costs and effectiveness. Of these evaluations, three evaluations concluded in favor of the implementation of POCT, while one concluded against its implementation since POCT was both more expensive and less effective. The remaining five evaluations could not conclude with certainty whether or not POC should be implemented for monitoring in primary care. Two of these evaluations concluded that even though POCT dominated usual care, POCT is only likely to be cost effective in settings without access to laboratory services. The remaining three evaluations did find that POCT has a chance of being cost effective, but that this chance depends (heavily) on the value society would place on the effectiveness outcome or that more precision in their estimations is required. The five evaluations that only reported costs and a measure of effectiveness (without an associated ratio) all concluded in favor of POCT, with four of the five reporting reduced costs due to POCT and all five reporting increased effectiveness.

3.4 Methodological Characteristics

An overview of the methodological characteristics of the publications is provided in Table 2. Most of the health economic evaluations were labeled by the publications in the title, abstract, or methods section as a cost-effectiveness analysis (n = 27; 61.4%). Additionally, two publications described both a cost-effectiveness analysis and cost-benefit analysis, and two publications described both a cost-effectiveness and budget-impact analysis. The time horizon applied in evaluations ranged from 28 days to a lifelong time horizon. There were ten publications that failed to indicate the selected time horizon. This would mean their results cannot be interpreted nor compared with those of other studies investigating the same POC test. A 6-month and lifelong time horizon were applied most often (both n = 5; 11.4%) followed by a 28-day period (n = 3; 6.8%).

The majority of the publications (n = 26; 59.1%) were classified as model-based and used a decision-analytic model to describe the health economic evaluation. The remaining publications (n = 18; 40.9%) were classified as trial-based. The most popular choice of model was a decision tree (n = 15) followed by a Markov model (n = 7). There were also two studies combining these modeling methods. Only three of the 18 trial-based evaluations made use of a simulation model. One of these publications used data collected during a trial as input for a decision tree model and one as input for a Markov model. The other used a regression model to analyze trial data.

The evaluations were mostly performed from a healthcare system perspective (n = 14; 31.8%), societal perspective (n = 7; 15.9%) and healthcare provider perspective (n = 4; 9.1%). The healthcare system perspective relates to the perspective of the entire (nationwide) healthcare organization whereas the healthcare provider perspective relates to the perspective of a single type of provider, such as GPs. Nine (20.5%) of the publications failed to indicate the perspective of the study. More than 60% of publications (n = 28; 63.6%) made use of a sensitivity analysis to assess the uncertainty of results. Of these, 15 performed a deterministic analysis only (five trial based; ten model-based), eight performed a probabilistic analysis only (one trial-based evaluation including bootstrapping; seven model-based evaluations including a probabilistic analysis), and five evaluations applied both deterministic and probabilistic analyses (all model-based). The remaining 16 publications did not apply any sensitivity analysis and mainly concerned trial-based evaluations (n = 9).

3.5 Quality of Publications

Two of the publications [24, 25] reported all of the applicable items in the CHEERS checklist. Compliance with the checklist items ranged from 20.8 to 100%, with an average of 72.0%. There were three publications [26,27,28] that were classified as being of low reporting quality, with a score of < 50%. Almost half of the publications (n = 21; 47.7%) were considered of high reporting quality with a score of > 75%, the remainder of the publications (n = 20; 45.5%) were medium quality. The worst scoring criteria items were time horizon, discount rate, target population and subgroups, and study perspective. Publications focusing on primary care had an average score of 75.2%, whereas publications focusing on secondary care had an average score of 65.7%. Generally, publications evaluating POC tests as a diagnostic tool scored slightly higher (75.35% for primary care, 72.2% for secondary care) compared with monitoring (74.8% for primary care, 64.0% for secondary care) and screening (74.5% for primary care, 58.5% for secondary care).

4 Discussion

The heath economic benefits of POCT reported most often by evaluations in this review was that it allows early diagnosis, a decrease in the number of hospitalizations and referrals to specialized care, reduced risks of infection and antibiotic prescription, and a decrease in additional burden and costs associated with referrals and additional testing. Some of the evaluations, specifically those incorporating a longer time horizon, even found that the costs continue to decrease over time when POCT is implemented. There were very few evaluations that recommended against the implementation of POCT. Three evaluations found that the benefits of implementing POCT do not outweigh the increase in cost. One evaluation found, during the implementation of POCT in a trial, that clinicians choose not to adhere to the results of the test. They concluded from a sensitivity analysis that only with higher adherence to test results would POCT be cost effective. Similarly, a few publications mentioned that POCT is more effective with closer adherence to clinical guidelines.

Although the publications included were, on average, considered to be of medium reporting quality, there are some important criteria items that were generally not reported on. Firstly, although most of the publications described the health economic assessment within a specific timeframe, it was rarely explained why the selected timeframe was chosen. Secondly, the cost effectiveness of an intervention is conditional to the target population [29]; therefore, providing a sufficient description or reference of the considered population is essential for the correct interpretation of results. In several of the publications, however, the target population and subgroups were poorly described. The lack of reporting on these items might limit the usefulness of these evaluations to policy and decision makers. However, it is important to note that the CHEERS checklist only reflects the way evaluations are reported and communicated, and not necessarily the quality of how they were conducted. Furthermore, the overall reporting quality of publications evaluating POC tests implemented as a diagnostic is slightly higher than that of publications evaluating POC tests for screening and monitoring. However, there are not enough publications evaluating screening and monitoring POC tests to draw robust conclusions about purpose-related quality.

There were three common limitations observed in the evaluations in this review. Firstly, the whole healthcare system and clinical pathways were not always considered, only a specific cohort in a generally small setting. Secondly, only a few specific outcome measures were selected to evaluate the impact that POCT could have, omitting other outcome measures that could be relevant [30]. A third observed limitation was the limited evidence available to populate models, which often leads to assumptions having to be made [31], especially regarding prescribing behavior related to PCT test results and adherence to treatment. When properly accounted for, such assumptions or limited evidence led to substantial uncertainty in the results. Regarding adherence and behavior data from protocolized randomized trials may also not be optimal to use in models, as these data may not reflect actual real-world use and interpretation of POC test outcomes.

This review confirmed the wide range and applicability of POCT. Evaluations ranged from POC tests used by general practitioners to prevent unnecessary treatment and referrals to the emergency room where the rapid diagnosis allows patients to be discharged more quickly. Further value is added by POCT through increased patient satisfaction and overall improvement in care provision [1, 15]. In addition to these benefits, the implementation of POCT may also have a negative impact; for example, an increase in costs, increased labor requirements, and alterations to the processes and workflow [32, 33]. These aspects could discourage GPs and care providers from implementing POCT in their practice [34].

Considering that POCT is accompanied by both potential benefits and potential burdens, it is necessary to establish that the implementation of POCT in practice will have sufficient benefits to justify the burdens. From this review, it is apparent that many publications find POCT to be a valuable counterpart to traditional laboratory testing or usual care. However, POCT should not always be perceived as cost saving. Some publications indicated that implementing POCT would result in higher costs, but this was justified by the long-term gains such as increased life expectancy, reduced unnecessary referrals to specialists, unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions, and decreased length of stay. It is important to recognize that the cost effectiveness of POCT in general will likely vary according to the target disease, and the cost effectiveness of specific POC tests can vary according to the population and setting [35].

The implementation and utilization of POC tests will not be reliant on technical advancements alone, but also on the changes in costing systems and reimbursement practices. Health system resources are limited, and it is essential to ensure that the resources allocated to diagnostics, such as POC tests, are optimized. Health economic evaluations are often conducted to contribute to and inform on such decisions. This review showed that high-quality health economic evaluations on POCT are limited. It is highly recommended that future health economic evaluations follow a formal checklist, such as the CHEERS [22] or AGREEDT (AliGnment in the Reporting of Economic Evaluations of Diagnostic Tests and biomarkers) [36] checklists, when reporting to ensure that all of the important criteria are included in the final evaluation report. This might also, indirectly, increase the quality of the evaluations themselves if such checklists are considered during the evaluation process itself rather than when reporting results at the end.

In general, the results of the health economic evaluations that were included in this review are somewhat limited or non-transferrable. In most cases, the evaluations are described and set up to meet the local needs and requirements, which resulted in studies that are cohort-specific and have a limited scope. Consequently, the evidence generated from these evaluations is not as comprehensive as it could have been. In a study using HbA1c as an exemplar, it has also been suggested that the benefits of POCT are not realized, in part because it is not measured in studies [37]. While dimensions of value and relevant impact elements for POCT have been defined in literature [30, 36], including all of these is very challenging [38], foremost due to a common lack of evidence on the expected benefits in certain dimensions.

Even though the evaluations included in this review did not always include the full long-term benefits of POCT, it is clear that health economic evidence across a few dimensions of value already indicate the benefits of POCT. Previous systematic reviews [18, 19] reported that more health economic evidence is necessary to guide the expansion of the use of POCT. As seen in this review, the health economic evidence has increased and provides promising evidence, with about 77% of the health economic evaluations included in this review concluding in favor of implementing POCT. However, regardless of the increase in health economic evidence, the overall uptake of POCT remains slow [17, 37, 39]. This suggests that the lack of health economic evidence on POCT is not the primary barrier to the expansion of POCT and that the slow uptake of these tests in clinical practice is due to (a combination of) other barriers. It is also possible that the system-level evidence provided in health economic evaluations is irrelevant to the local stakeholders in charge of the implementation of POCT [21]. In this context, aspects around organization of care, support of clinicians and quality management may be crucial in the widespread implementation of POCT.

References

Jordan B, Mitchell C, Anderson A, Farkas N, Batrla R. The clinical and health economic value of clinical laboratory diagnostics. Ejifcc. 2015;26(1):47–62.

Bossuyt PMM, Reitsma JB, Linnet K, Moons KGM. Beyond diagnostic accuracy: the clinical utility of diagnostic tests. Clin Chem. 2012;58(12):1636–43.

Dugum M, McCullough AJ. Diagnosis and management of alcoholic liver disease. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2015;3:109–16.

Sidhu MS, Dellsperger KC. Cardiovascular problems in dialysis patients: impact on survival. Adv Perit Dial. 2010;26:47–52.

Celermajer DS, Chow CK, Marijon E, Anstey NM, Woo KS. Cardiovascular disease in the developing world: prevalences, patterns, and the potential of early disease detection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(14):1207–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.074.

Griffin SJ, Little PS, Hales CN, Kinmonth AL, Wareham NJ. Diabetes risk score: towards earlier detection of Type 2 diabetes in general practice. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2000;16:164–71.

Christodoulides N, Floriano PN, Sanchez X, et al. Programmable Bio-NanoChip Technology for the Diagnosis of Cardiovascular Disease at the Point of Care. Method DeBakey Cardiovasc J. 2012;8(1):6–12.

Burns FM, Johnson AM, Nazroo J, Ainsworth J, Anderson J, Fakoya A, et al. Missed opportunities for earlier HIV diagnosis within primary and secondary healthcare settings in the UK. Aids. 2008;22:115–22.

Price D, Freeman D, Cleland J, Kaplan A, Cerasoli F. Earlier diagnosis and earlier treatment of COPD in primary care. Prim Care Respir J. 2011;20(1):15–22. https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2010.00060.

Schols AMR, Dinant GJ, Hopstaken R, Price CP, Kusters R, Cals JWL. International definition of a point-of-care test in family practice: a modified e-Delphi procedure. Fam Pract. 2018;35(4):475–80.

Cals J, Van Weert H. Point-of-care tests in general practice: hope or hype? Eur J Gen Pract. 2013;19(4):251–6.

Sohn AJ, Hickner JM, Alem F. Use of point-of-care tests (POCTs) by US primary care physicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(3):371–6. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2016.03.150249.

Kankaanpää M, Raitakari M, Muukkonen L, Gustafsson S, Heitto M, Palomäki A, et al. Use of point-of-care testing and early assessment model reduces length of stay for ambulatory patients in an emergency department. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24(125):1–7.

Kozel TR, Burnham-Marusich AR. Point-of-care testing for infectious diseases: past, present, and future Thomas. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(8):2313–20.

Laurence CO, Gialamas A, Bubner T, Yelland L, Willson K, Ryan P, et al. Patient satisfaction with point-of-care testing in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(572):166–71.

Lingervelder D, Koffijberg H, Kusters R, Ijzerman MJ. Point-of-care testing in primary care: a systematic review on implementation aspects addressed in test evaluations. Int J Clin Pract. 2019;73(10):1–12.

Korte BJ, Rompalo A, Manabe YC, Gaydos CA. Overcoming challenges with the adoption of point-of-care testing. Point Care J Near-Patient Test Technol. 2020;19(3):77–83.

Hobbs FDR, Delaney B, Fitzmaurice DA, Wilson S, Hyde CJ, Thorpe GH, et al. A review of near patient testing in primary care. Health Technol Assess (Rockv). 1997;1(5):1–229.

Nichols JH, Christenson RH, Clarke W, Gronowski A, Hammett-Stabler CA, Jacobs E, et al. Executive summary. The National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory Medicine Practice Guideline: Evidence-based practice for point-of-care testing. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;379(1–2):14–28.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Altman D, Antes G, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement (Chinese edition). J Chin Integr Med. 2009;7(9):889–96.

St John A, Price CP. Economic evidence and point-of-care testing. Clin Biochem Rev. 2013;34(2):61–74.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS ) statement. BMC Med. 2013;11(80)

Owusu-Edusei K, Gift TL, Ballard RC. Cost-effectiveness of a dual non-treponemal/treponemal syphilis point-of-care test to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(11):997–1003.

Hunter R. Cost-effectiveness of point-of-care C-reactive protein tests for respiratory tract infection in primary care in England. Adv Ther. 2015;32(1):69–85.

Whiting P, Al M, Westwood M, Ramos IC, Ryder S, Armstrong N, et al. Viscoelastic point-of-care testing to assist with the diagnosis, management and monitoring of haemostasis: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess (Rockv). 2015;19(58):1–228.

Spaeth B, Shephard M, Kokcinar R, Duckworth L, Omond R. Impact of point-of-care testing for white blood cell count on triage of patients with infection in the remote Northern Territory of Australia. Pathology. 2019;51(5):512–7.

Henson G, Ghonim E, Swiatlo A, King S, Moore K, King S, et al. Cost-benefit and effectiveness analysis of rapid testing for MRSA carriage in a hospital setting. Clin Lab Sci J. 2014;27(1):13–20.

Kong MC, Lim TG, Ng HJ, Chan YH, Lee LH. Feasibility, cost-effectiveness and patients’ acceptance of point-of-care INR testing in a hospital-based anticoagulation clinic. Ann Hematol. 2008;87(11):905–10.

Coyle D, Buxton MJ, Brien BJO. Stratified cost-effectiveness analysis: a framework for establishing efficient limited use criteria. Health Econ. 2003;12:421–7.

Wurcel V, Cicchetti A, Garrison L, Kip MMA, Koffijberg H, Kolbe A, et al. The value of diagnostic information in personalised healthcare: a comprehensive concept to facilitate bringing this technology into healthcare systems. Public Health Genom. 2019;22:8–15.

Annemans L, Redekop K, Payne K. Current methodological issues in the economic assessment of personalized medicine. Value Health. 2013;16(6 SUPPL.):S20–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2013.06.008.

Haga SB. Challenges of development and implementation of point of care pharmacogenetic testing. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2016;16(9):949–60.

Huckle D. The impact of new trends in POCTs for companion diagnostics, non-invasive testing and molecular diagnostics. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015;15(6):815–27.

Benjamin Crocker J, Lee-Lewandrowski E, Lewandrowski N, Baron J, Gregory K, Lewandrowski K. Implementation of point-of-care testing in an ambulatory practice of an academic medical center. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;142(5):640–6.

Grieve R, Beech R, Vincent J, Mazurkiewicz J. Near patient testing in diabetes clinics: Appraising the costs and outcomes. Health Technol Assess (Rockv). 1999;3(15).

Kip MMA, Ijzerman MJ, Henriksson M, Merlin T, Weinstein MC, Phelps CE, et al. Toward alignment in the reporting of economic evaluations of diagnostic tests and biomarkers: the AGREEDT checklist. Med Decis Mak. 2018;38(7):778–88.

Price CP, St John A. The value proposition for point-of-care testing in healthcare: HbA1c for monitoring in diabetes management as an exemplar. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2019;79(5):298–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365513.2019.1614211.

Breheny K, Sutton AJ, Deeks JJ. Model-based economic evaluations of diagnostic point of care tests were rarely fit for purpose. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;109:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.11.003.

Howick J, Cals JWL, Jones C, Price CP, Pluddemann A, Heneghan C, et al. Current and future use of point-of-care tests in primary care: an international survey in Australia, Belgium, The Netherlands, the UK and the USA. BMJ Open. 2014;4(8):e005611.

Frank SC, Cohn J, Dunning L, Sacks E, Walensky RP, Mukherjee S, et al. Clinical effect and cost-effectiveness of incorporation of point-of-care assays into early infant HIV diagnosis programmes in Zimbabwe: a modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2019;3018(18):1–9.

Goldstein LN, Wells M, Vincent-Lambert C. The cost of time: a randomised, controlled trial to assess the economic impact of upfront, point-of-care blood tests in the Emergency Centre. African J Emerg Med. 2019;9(2):57–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2019.01.011.

Gout-Zwart JJ, Olde Hengel EHJ, Hoogland P, Postma MJ. Budget impact analysis of a renal point-of-care test in Dutch community pharmacies to prevent antibiotic-related hospitalizations. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2019;17(1):55–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-018-0426-2.

Lee DJ, Kumarasamy N, Resch SC, Sivaramakrishnan GN, Mayer KH, Tripathy S, et al. Rapid, point-of-care diagnosis of tuberculosis with novel Truenat assay: cost-effectiveness analysis for India’s public sector. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(7):1–17.

Pooran A, Theron G, Zijenah L, Chanda D, Clowes P, Mwenge L, et al. Point of care Xpert MTB / RIF versus smear microscopy for tuberculosis diagnosis in southern African primary care clinics: a multicentre economic evaluation. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(6):e798-807. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30164-0.

Rahamat-Langendoen J, Melchers WJG, Van Der WGJ. Impact of molecular point-of-care testing on clinical management and in-hospital costs of patients suspected of influenza or RSV infection: a modeling study. J Med Virol. 2019;91(January):1408–14.

Rajasingham R, Pollock NR, Linas BP. The Cost-effectiveness of a Point-of-Care Paper Transaminase Test for Monitoring Treatment of HIV/TB Co-Infected Persons. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(4).

Esteve M, Rosinach M, Llordés M, Calpe J, Montserrat G, Pujals M, et al. Case-finding in primary care for coeliac disease: accuracy and cost-effectiveness of a rapid point-of-care test. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(6):855–65.

Holmes EAF, Harris SD, Hughes A, Craine N, Hughes DA. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the use of point-of-care C-reactive protein testing to reduce antibiotic prescribing in primary care. Antibiotics. 2018;7(4):106.

Lubell Y, Do NTT, Nguyen KV, Ta NTD, Tran NTH, Than HM, et al. C-reactive protein point of care testing in the management of acute respiratory infections in the Vietnamese primary healthcare setting—a cost benefit analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7:1–6.

Spaeth BA, Kaambwa B, Shephard MDS, Omond R. Economic evaluation of point-of-care testing in the remote primary health care setting of Australia’s Northern Territory. Clin Outcomes Res. 2018;10:269–77.

El-Osta A, Woringer M, Pizzo E, Verhoef T, Dickie C, Ni MZ, et al. Does use of point-of-care testing improve cost-effectiveness of the NHS Health Check programme in the primary care setting? A cost-minimisation analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e015494.

Hyle EP, Rosettie KL, Osher B, Maggiore P, Parker RA, Peter T, et al. The value of point-of-care CD4+ and laboratory viral load in tailoring antiretroviral therapy monitoring strategies to resource limitations. Aids. 2017;31(15):2135–45.

Kip MMA, Koffijberg H, Moesker MJ, Ijzerman MJ, Kusters R. The cost-utility of point-of-care troponin testing to diagnose acute coronary syndrome in primary care. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17:1–9.

Lewandrowski E, Yeh S, Baron J, Crocker JB, Lewandrowski K. Implementation of point-of-care testing in a general internal medicine practice : A con fi rmation study. Clin Chim Acta. 2017;473(August):71–4.

You JHS, Tam LP, Lee NLS. Cost-effectiveness of molecular point-of-care testing for influenza viruses in elderly patients at ambulatory care setting. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7):1–11.

Heffernan A, Barber E, Thomas R, Fraser C, Pickles M, Cori A. Impact and cost-effectiveness of point-of-care CD4 testing on the HIV epidemic in South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7):1–12.

Janković SM, Kostić M. Cost-effectiveness of introducing point-of-care test for detection of level of glycogen phosphorylase in early diagnostic algorithm of acute coronary syndrome. Value Heal Reg Issues. 2016;10:79–84.

Ward MJ, Self WH, Singer A, Lazar D, Pines JM. Cost-effectiveness analysis of early point-of-care lactate testing in the emergency department. J Crit Care. 2016;36:69–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.06.031.

Whitney RE, Santucci K, Hsiao A, Chen L. Cost-effectiveness of point-of-care testing for dehydration in the pediatric ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(8):1573–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2016.05.075

Challen L, Agbahiwe S, Cantieri T, Olivetti JG, Mbah T, Mendoza-becerra Y, et al. Impact of point-of-care implementation in pharmacist-run anticoagulation clinics within a community-owned health system: a two-year retrospective analysis. Hosp Pharm. 2015;50(9):783–8.

Ciaranello AL, Myer L, Kelly K, Christensen S, Daskilewicz K, Doherty K, et al. Point-of-Care CD4 testing to inform selection of antiretroviral medications in South African antenatal clinics : a cost- effectiveness analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117751

Hendriksen JM, Geersing GJ, Van Voorthuizen SC, Oudega R, Ten Cate-Hoek AJ, Joore MA, et al. The cost-effectiveness of point-of-care D-dimer tests compared with a laboratory test to rule out deep venous thrombosis in primary care. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015;15(1):125–36.

Asha SE, Fat Chan AC, Walter E, Kelly PJ, Morton RL, Ajami A, et al. Impact from point of care devices on emergency department patient processing times compared to central laboratory testing of blood samples: a randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Emerg Med J. 2014;31(9):714–9.

Crocker BJ, Lee-Lewandrowski E, Lewandrowski N, Baron J, Gregory K, Lewandrowski K. Implementation of point-of-care testing in an ambulatory practice of an academic medical center. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;142(5):640–6.

Chadee A, Blackhouse G, Goeree R. Point-of-care hemoglobin A1ctesting: a budget impact analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2014;14(9):1–23.

Resch S, Lehe J, Su AE, Jani IV, Peter T, Quevedo J, et al. The clinical and economic impact of point-of-care CD4 testing in Mozambique and other resource-limited settings: a cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(9):e1001725.

Nilsson S, Andersson A, Janzon M, Karlsson J, Levin L, Nilsson S, et al. Cost consequences of point-of-care troponin T testing in a Swedish primary health care setting cost consequences of point-of-care troponin T testing in a Swedish primary health care setting. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2014;32(4):241–7.

Turner KME, Round J, Horner P, Macleod J, Goldenberg S, Deol A, et al. An early evaluation of clinical and economic costs and benefits of implementing point of care NAAT tests for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoea in genitourinary medicine clinics in England. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90:104–11.

Huang W, Gaydos CA, Barnes MR, Jett-Goheen M, Blake DR. Comparative effectiveness of a rapid point-of-care test for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis among women in a clinical setting. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(2):108–14.

Oppong R, Jit M, Smith RD, Butler CC, Melbye H, Mölstad S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of point-of-care C-reactive protein testing to inform antibiotic prescribing decisions. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(612):465–71.

Van Dyck W, Vértes G, Palaniappan M, Gassull D, Jain P, Schulthess D, et al. Acute coronary syndrome: what is the cost-effectiveness of prevention, point-of-care technology and telemonitoring? Health Policy Technol. 2012;1(3):173–7.

Cals JWL, Ament AJHA, Hood K, Butler CC, Hopstaken RM, Wassink GF, et al. C-reactive protein point of care testing and physician communication skills training for lower respiratory tract infections in general practice: economic evaluation of a cluster randomized trial. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(6):1059–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01472.x.

Fitzgerald P, Goodacre S, Cross E, Dixon S. Cost-effectiveness of point-of-care biomarker assessment for suspected myocardial infarction: the randomized assessment of treatment using panel assay of cardiac markers (RATPAC) trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(5):488–95.

Owusu-Edusei K, Gift TL, Ballard RC. Cost-effectiveness of a dual test to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(11):997–1003.

Golden AB, Hill JA, O’Riordan MA, Sandhaus LM. Point-of-care blood gas analysis in the pediatric cardiac catheterization suite: a clinical outcome study. Point Care. 2010;9(2):108–10.

Laurence CO, Moss JR, Briggs NE, Beilby JJ. The cost-effectiveness of point of care testing in a general practice setting: Results from a randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10.

Rydzak CE, Goldie SJ. Cost-effectiveness of rapid point-of-care prenatal syphilis screening in sub-Saharan Africa. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(9):775–84.

Udeh B, Schneider J, Ohsfeldt R. Cost effectiveness of a point-of-care test for adenoviral conjunctivitis. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336(3):254–64.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

DL: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, visualization. MJI: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision. HK: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing. GCMK: conceptualization, writing—review and editing.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lingervelder, D., Koffijberg, H., Kusters, R. et al. Health Economic Evidence of Point-of-Care Testing: A Systematic Review. PharmacoEconomics Open 5, 157–173 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-020-00248-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-020-00248-1