Abstract

Background

Severe hypertriglyceridemia (sHTG) is a rare condition, complicated by episodes of acute pancreatitis (AP), which can cause pain and/or life-threatening multi-organ dysfunction. Currently, there are no disease-specific patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures evaluating symptoms or dietary impact for this condition.

Objective

The objective of this study was to explore patient-reported symptoms and impacts of sHTG and AP and develop new measures to capture the symptoms and dietary impacts of this condition using patient language.

Methods

In-depth, semi-structured concept elicitation interviews were conducted with 12 US-based participants to explore their experience and identify key symptoms and impact on dietary behavior, both during and between episodes of AP. Participants had a range of AP severity with a previous triglyceride reading > 1000 mg/dL, and at least one attack of AP within the last 12 months. Transcripts were coded using thematic analysis.

Results

Qualitative data analysis revealed the substantial burden of AP associated with sHTG. Participants reported experiencing symptoms, especially abdominal pain, both during and between attacks of AP, and discussed considerable diet changes to prevent or minimize future attacks. A conceptual model was refined, based on patient input, and reviewed by clinical experts to determine key concepts for inclusion within two PRO measures, one evaluating symptoms and another evaluating impact on dietary behavior. Items were drafted using patient-derived language. A 19-item symptoms measure [Hypertriglyceridemia and Acute Pancreatitis Symptom Scale (HAP-SS)] and a 6-item dietary impact measure (Hypertriglyceridemia and Acute Pancreatitis Dietary Behavior (HAP-DB) measure) were developed, both with a 24-h recall period.

Conclusions

The qualitative analysis confirmed the substantial burden of AP associated with sHTG. This research resulted in development of two disease-specific PRO measures for use during and between attacks of AP. These measures are being utilized in a clinical trial, which will confirm content, structure, and psychometric properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Patients reported experiencing a range of symptoms and dietary impacts relating to their severe hypertriglyceridemia and acute pancreatitis which were burdensome and impacted their life. |

Using patient language, two measures were developed to capture the key symptoms and dietary impacts discussed by participants as being important to them. |

Both measures are being utilized in a clinical trial to further confirm content and structure. |

1 Background

Severe hypertriglyceridemia (sHTG) is a rare condition characterized by serum triglycerides (TGs) > 1000 mg/dL (> 11.3 mmol/L), which is significantly greater than the expected level for the general population of approximately 150 mg/dL. Individuals with sHTG are at increased risk for acute pancreatitis (AP), which can cause variable inflammation, pain, and/or life-threatening multi-organ dysfunction [1,2,3,4,5].

The prevalence of sHTG in the USA is reported as 1.7% of the population [1]. Hypertriglyceridemia (HTG) is one of the most identifiable etiologies of AP after gallstones and alcohol, accounting for approximately 2–4% of cases [2,3,4,5]. In the USA, AP is one of the most frequent gastrointestinal causes for hospitalization, accounting for 275,170 hospitalizations and 2000 deaths in 2012 [6]. Cases of AP can range from mild to severe and may result in prolonged hospitalization, significant morbidity, and, in some cases, mortality [7]. Individuals experiencing AP associated with sHTG can experience a range of symptoms and dietary impacts related to their condition; however, current literature suggests that symptoms of AP due to sHTG are consistent with symptoms of AP of other etiologies [8,9,10]. It is important to assess these key aspects of AP associated with sHTG as part of a comprehensive measurement strategy evaluating the impact, management, and treatment of this condition. Currently, there are no disease-specific patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures evaluating signs and symptoms or dietary impact among patients who experience the effects of AP associated with sHTG, either during or between episodes of AP.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Guidance for Industry on the use of PRO measures in medical product development [11] clearly outlines the importance of obtaining the patient perspective in the development of any patient-focused outcome measure to ensure that all relevant concepts are appropriately incorporated into the measure. Qualitative research with the target population is necessary to demonstrate content validity. Any additional psychometric evaluation of the measure will only build upon this foundation.

Therefore, the purpose of the current research is to understand the individual patient experience of AP associated with sHTG, identify the symptoms and impacts that are important, and use that information to develop two PRO measures that capture the salient signs and symptoms and dietary impact of this condition.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design and Participants

Indepth, concept elicitation, semi-structured, qualitative interviews were conducted by the second author (JAR) in April/May 2017 with US-based participants who had clinician confirmed AP associated with sHTG [12,13,14]. The study was designed and conducted in line with established good research practices, including the guidelines provided by the ISPOR (International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research) taskforce [15]. The study design was not restricted to a single qualitative, methodological framework, but was more unstructured to allow for an open exploration of the participant experience of AP associated with sHTG.

Patients were identified using purposive sampling from clinicians working at the University of Pittsburgh (PA, USA). Following identification, participants were approached face-to-face and presented with an informed consent form. All participants who signed the consent form were enrolled and no participants withdrew from the study. Eligibility of consented participants was confirmed by disease area expert clinicians at the University of Pittsburgh.

Patients were eligible if they were over 18 years of age, had a serum TG measurement ≥ 500 mg/dL, and had experienced an AP attack in the last 24 months. Patients were excluded from the study if their pancreatitis was primarily caused by gallstones, alcohol, or trauma, or had uncontrolled endocrine disease (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism), severe concomitant illnesses with chronic or acute pain, or any medical or psychiatric condition that may interfere with their discussion of their symptoms or areas of impacts during the study.

2.2 Interviews

A discussion guide (Electronic Supplementary Material Appendix A) was developed based on input from disease area expert clinicians and information found from the existing qualitative/PRO development literature in a similar disease area: lipoprotein lipase deficiency [16, 17]. Questions in the discussion guide were designed to allow for spontaneous concept elicitation by participants. Interviews were conducted by the second author (JAR), who is an expert qualitative researcher who has worked in the field for many years and was employed as a qualitative researcher at the time of the study. All interviews were conducted in a local hotel meeting room and lasted approximately 60 min. Prior to the interview commencing, the interviewer spent time developing a rapport with the participant and discussed the nature and reasons for conducting this research.

Each interview began with open-ended, non-leading questions designed to understand concepts important to the participant. If the concept was not spontaneously elicited by the participants, only then were direct questions and probing used.

After the concept elicitation section of the interview, generic item shells were presented to the participant to facilitate feedback about ways in which symptoms and impacts could be measured in this population. These generic item shells included example item wording using different terminology (e.g., 24 h/today) and response options (numeric rating scales (NRS), severity and frequency Likert-type scales), and recall periods (24 h and today). Participants were asked to consider whether they preferred items asking about their symptoms on ‘average’ or ‘at worst’. Finally, participants were asked about the recall period, including how long they thought they could accurately recall details around each symptom they had previously mentioned.

2.3 Analytical Approach

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were de-identified and analyzed using inductive thematic analysis [18] in ATLAS.ti version 7.0 (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The use of thematic analysis involves reading and re-reading the transcripts to identify codes and themes [18]. Codes and themes are developed using patient language.

In the current study, one researcher [second author (JAR)] undertook all the coding for thematic analysis. The accuracy of thematic analysis [18] was confirmed by the study lead [first author (CB)] who reviewed all codes across a selection of the transcripts to ensure that this was being applied consistently. There was agreement that the coding was being applied consistently and that this reflected participant language, and therefore updates to the coding were not needed.

Saturation analysis was undertaken, using both spontaneous and probed responses, by dividing the sample into three equal groups, based on the chronological order in which participants were interviewed. Saturation was considered met when no new topics were discussed in the final group of participants; thus, it is deemed that no more interviews were necessary [19].

2.4 Ethics

All study documents were submitted and approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (IRB). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and US 21 Code of Federal Regulations [20]. Participants received a small stipend for their participation. All data were de-identified before analysis.

3 Results

A total of 12 participants were interviewed. Participants’ age ranged from 28 to 63 years, with the majority being male [8 (67%)] and white [10 (83.3%)]. All patients were being treated to lower their sHTG levels and presented with a previous serum TG measurement ≥ 1000 mg/dL (eligibility requirement was ≥ 500 mg/dL) along with a history of a hospitalization due to AP associated with HTG. Although based on clinician-reported symptoms, one participant was just outside the eligibility criteria because their physician-reported last AP attack was just outside the 24-month window at the time of the interview; they were within this time window at screening. However, once participant-reported information was obtained, all 12 participants self-reported at least one AP attack in the past 12 months. This discrepancy is due to participants managing AP attacks at home. Five participants reported more than one attack over the past 5 years (one reported two attacks and four reported three or more over the past 5 years). Participants were recruited as close as possible to their last AP attack. The mean (± standard deviation) time since their last AP attack was 5.6 (± 3.54) months, ranging from 1 to 11 months ago. The AP severity was clinician reported using a 4-point scale ranging from none to severe, using the reviewed Atlanta classification and definitions agreed upon in 2012 [21]. Participants had a range of AP severity; one was severe, six were moderate, and five were mild. Participant demographics are presented in Table 1.

Overall, the analysis of qualitative data from the interviews revealed a substantial burden of AP associated with sHTG. During the interviews, the symptoms discussed reflected not only those experienced on a day-to-day basis (chronic symptoms), but also those the participant could recall from their last attack of AP (acute symptoms). Participants described their attack of AP as being so severe, often involving hospitalization, that they had no difficulties recalling what their symptoms were during an AP attack, even those for whom this was 11 months prior to interview.

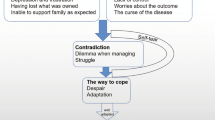

A number of symptoms and impacts were identified by the participants as being of importance to them (Table 2). These were organized into a conceptual model which is shown in Fig. 1.

3.1 Symptoms Experienced

The symptoms identified could be broadly grouped into three categories: pain and abdominal symptoms (12 symptoms), physical symptoms (ten symptoms), and other symptoms (five symptoms).

Pain and abdominal symptoms were key symptoms present in all patients. All patients reported experiencing acute intermittent abdominal pain, both during and between attacks of AP, which was severe and intense. Six participants also experienced a persistent background abdominal pain, and eight reported experiencing additional intense abdominal pain after eating. All but one participant reported back pain.

Additional symptoms were reported, as highlighted in Fig. 1. Nausea, fatigue, abdominal distension/bloating, excessive sweating, and being hungry just after eating were most commonly reported other symptoms (by ≥ 75% of participants). The least commonly discussed symptoms (discussed by ≤ 25% of participants) were a fatty lump on the knee, indigestion, headaches, excessive thirst, and chest pain.

Most of the aforementioned symptoms were reported as being experienced both between and during an attack of AP. Symptoms directly related to eating, which were highlighted as important to the participants, were only experienced between attacks because most people reported that they avoid eating during an attack.

3.2 Areas of Impact

All participants reported making substantial dietary changes designed to prevent or minimize an attack of AP associated with sHTG. During an attack, most participants reported severe restriction or avoidance of food intake. However, most dietary changes discussed were long-term changes to diet to avoid symptoms or prevent attacks. Most commonly reported (≥ 75% of participants) changes were restrictions to carbohydrate intake, greasy fatty food, reduced food volume, and alcohol restrictions/limitations. Calorie counting, eating soft foods, cutting out meat, and skipping meals were less commonly reported (≤ 25% of participants).

Alongside dietary impacts, a small number of participants also discussed a negative impact on mood. This included anxiety, low mood, and irritability.

3.3 Saturation

Saturation analysis showed that there was consistency in the symptoms and impacts spontaneously raised across all interviews. When the probed responses were also considered, this showed that no new symptoms or areas of impact were being identified in the final group of interviews, except for one symptom ‘fatty lump on knee’, which was only identified by one participant. This symptom was discussed indepth by the research team along with two disease area expert clinicians as to whether additional interviews were needed to reach saturation on this symptom. The disease area expert clinicians confirmed that this is an uncommon symptom, and one which they had only seen a couple of times in their patients. They suggested that even if we were to continue interviewing, we would be unlikely to ever come across a patient with this symptom again. Therefore, the research team decided that further interviews were not required.

3.4 Feedback on Generic Item Shells

Based on the generic item shells discussed at the end of the interview, participants felt that asking about either frequency or severity could capture their sHTG and AP symptomatic experience. All response options [0–10 NRS, 5-point frequency or severity Likert-type scales, or simple checklist of symptoms experienced (yes/no)] were clearly understood by all participants. Participants reported no clear preference for one style over the other and indicated that any would be suitable for use to capture their symptom experience.

As part of this discussion, participants were asked about how long they could recall their symptoms, and to think about how this could be captured in the measure. Participants reported that they could clearly recall the symptoms they experienced related to their sHTG and AP daily and could also recall those that occurred during the last AP attack since these were so severe and often needed hospitalization. Furthermore, it was highlighted that these symptoms could change daily, particularly during an attack of AP.

3.5 Measure Development

All of the symptoms and areas of impact identified during the interviews were discussed at an item generation meeting by a team consisting of disease area expert clinicians and PRO development experts. Key symptoms and areas of impact were identified and agreed upon based on a range of characteristics, such as the number of participants reporting it, the frequency and severity reported by the participants, and how debilitating and how important participants reported it to be. Finally, feedback from PRO development experts was used to make sure that the symptoms and areas of impact included in the initial draft of the measure were suitable for patient report. Therefore, not all the symptoms and areas of impact identified in the conceptual model were included in the developed measures.

During the item generation meeting, 19 signs and symptoms and six dietary impacts were highlighted as key concepts for individuals with AP associated with sHTG. These are listed in Tables 3 and 4, along with participant quotes for each concept to demonstrate clearly the link between the participants’ voice and the items developed. Items were developed using participant language from the interviews and informed by participant feedback on preferred formats from the discussion on the generic item shells during the interview.

Following the item generation meeting, items for two new measures were drafted: one to capture signs and symptoms, the Hypertriglyceridemia and Acute Pancreatitis Symptom Scale (HAP-SS) measure; and one to capture dietary impacts, the Hypertriglyceridemia and Acute Pancreatitis Dietary Behavior (HAP-DB) measure. These included all 19 signs and symptoms and six dietary impacts identified as key concepts.

3.5.1 Measure Response Options

The response option format for the pain items in the HAP-SS is a 0- to 10-point severity-based NRS. Other HAP-SS and all HAP-DB items are captured on a 5-point frequency-based Likert-type scale. This was most reflective of the way that participants discussed their experiences, as participants mostly spoke about the severity of their pain and the frequency of other symptoms and impacts. NRS and Likert-type formats were selected as the clearest and most commonly used formats to capture severity and frequency, respectively.

3.5.2 Measure Recall Period

During the item generation meeting the developers agreed that a recall period of 24 h was appropriate for both measures. This was felt to be most appropriate for a measure that is planned for use within a clinical trial setting to capture the respondents present experience. Recording of symptoms in a daily diary is also in line with recommendations in the FDA PRO guidance [11].

4 Discussion

Qualitative analysis of the interviews confirmed the substantial burden of AP associated with sHTG as well as its impact on participants’ lives. The core symptoms experienced by individuals with AP associated with sHTG vastly affected individuals. It was clear from the qualitative findings that these could be severe and intense and were experienced both during and between attacks of AP. Additionally, to minimize the attack or to prevent future attacks, patients’ dietary habits were also severely impacted, with dietary limitations imposed both during and between attacks. Therefore, it is important to capture both long-term and acute symptoms and impacts of AP associated with sHTG in any planned measurement strategy for evaluating patient experience in this condition.

The conceptual model, which was updated following the interviews, shows the numerous symptoms that are commonly experienced by individuals with AP associated with sHTG. Although there were numerous symptoms and impacts reported, the key symptoms and impacts that were most salient to the participants could be clearly identified when reports of frequency and importance of these were considered. Some symptoms and impacts were identified that were either idiosyncratic and not frequently experienced or not reported to be of importance to the participant. These findings were reviewed and confirmed as part of a multi-disciplinary item generation meeting including disease area experts.

Although a small number of participants reported a negative impact on mood, and that this was important to them, it was agreed upon discussion with disease area experts that this was an example of a secondary impact of the condition, not a core symptom of AP associated with sHTG.

Although there are measures in similar conditions, which were used to inform the discussion guide during this study [16, 17], there are currently no disease-specific measures developed to capture the symptoms or dietary impact of AP associated with sHTG, either during or between episodes of AP, using patient input as part of the development process. Therefore, these findings were used to develop two new PRO measures to capture these symptoms and impacts for use within a clinical trial setting: the 19-item symptoms measure (HAP-SS) and the 6-item dietary impact measure (HAP-DB).

Development of these measures followed the processes outlined in the FDA Guidance for Industry on PROs [11]. The items in the measures were informed by the qualitative work and drafted using patient language. The research presented in this paper demonstrates a clear link between the qualitative data and the items. The HAP-SS and HAP-DB therefore have demonstrated content validity for use in this rare condition.

However, as these are draft measures, further work is necessary to continue the development and validation of these measures. The next step is to obtain empirical data to confirm content, structure, and psychometric properties of the measures, in addition to exploring meaningful change, as per the FDA Guidance for Industry on PROs [11]. The measures are currently being utilized in a clinical trial, the data from which will be used to conduct these analyses. These will be presented in a separate publication that will discuss the psychometric properties of the measures.

The number of participants involved in this study reflects the typical sample size for indepth qualitative research, particularly in a rare condition. For one symptom, fatty lumps on knee, it was not possible to reach saturation for this concept. In discussion with disease area clinical experts, clinicians confirmed that this is an uncommon symptom. A comprehensive evaluation of the coding confirmed that it was sufficient to reach saturation and fully explore all other symptoms and impacts. When assessing saturation in a rare disease there are other aspects that need to be taken into consideration. Indeed, the ISPOR taskforce highlighted that saturation in rare diseases may also require use of broader codes and confirmation from other sources, including previous literature and clinician feedback [22, 23]. These approaches were used in the current study to confirm concept coverage and support confirmation of saturation in this population.

Because AP due to sHTG is rare, it was challenging to recruit subjects. Participants for the study were recruited from only one location in the USA. There is no clinical reason to expect geographical variation in the symptoms experienced in this condition; however, the restriction to one site is a methodological limitation to this study and the generalizability of the results should be explored in future research. Participants were required to have had at least one attack of AP in the past 24 months, reported by the clinician, and were recruited as close to an attack of AP as possible. However, all participants self-reported an attack within the last 12 months. The time since last self-reported AP attack ranged from 1 to 11 months prior to interview. There was a discrepancy between clinician- and self-report of attacks due to participants reporting managing attacks at home. It was observed during the interviews that all participants were able to clearly recall and discuss the symptoms of an AP attack. An AP attack is a highly impactful event often involving severe symptoms and hospitalization. Therefore, issues with recall were not encountered. Most participants had been diagnosed for some time and had experienced multiple attacks, allowing for the exploration of chronic symptoms associated with AP due to sHTG. However, one participant had only been diagnosed the previous week and so they were only able to discuss acute symptoms. The decision was made to interview this person due to his willingness to participate and the symptom experience being very recent.

5 Conclusions

Qualitative analysis of the interviews confirmed the substantial burden of AP associated with sHTG, which occurred both during and between attacks. This research resulted in the development of two disease-specific PRO measures, for use in patients with AP associated with sHTG, both during and between attacks of AP, which have content validity: a 19-item symptoms measure (HAP-SS) and a 6-item dietary impact measure (HAP-DB). The measures are currently being utilized in a clinical trial, and further research will be used to confirm content, structure, and psychometric properties of the measures.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Christian JB, Bourgeois N, Snipes R, Lowe KA. Prevalence of severe (500 to 2,000 mg/dl) hypertriglyceridemia in United States adults. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(6):891–7.

Fortson MR, Freedman SN, Webster PD III. Clinical assessment of hyperlipidemic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(12):2134–9.

Saligram S, Lo D, Saul M, Yadav D. Analyses of hospital administrative data that use diagnosis codes overestimate the cases of acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(7):805–11.

Sandhu S, Al-Sarraf A, Taraboanta C, Frohlich J, Francis GA. Incidence of pancreatitis, secondary causes, and treatment of patients referred to a specialty lipid clinic with severe hypertriglyceridemia: a retrospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10(1):157.

Charlesworth A, Steger A, Crook MA. Acute pancreatitis associated with severe hypertriglyceridaemia; a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2015;23:23–7.

Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179–87.

Tenner S, Sica G, Hughes M, et al. Relationship of necrosis to organ failure in severe acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1997;113(3):899–903.

Scherer J, Singh V, Pitchumoni CS, Yadav D. Issues in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis—an update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(3):195–203.

Valdivielso P, Ramirez-Bueno A, Ewald N. Current knowledge of hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(8):689–94.

Zhang XL, Li F, Zhen YM, Li A, Fang Y. Clinical study of 224 patients with hypertriglyceridemia pancreatitis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015;128(15):2045–9.

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Fed Reg. 2009;74(235):65132–3.

Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. Los Angeles: Sage; 2013.

Murray M, Chamberlain K. Qualitative health psychology: theories and methods. London: Sage; 1999.

Willig C. Introducing qualitative research in psychology. 3rd ed. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education (UK); 2013.

Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity—establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: part 2—assessing respondent understanding. Value Health. 2011;14(8):978–88.

Guda NM, Freeman ML, Catalano MF, et al. Recurrent acute pancreatitis significantly impairs the quality of life Validation of RAPQOLI [abstract no. Mo1330]. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5 Suppl. 1):S-621.

Johnson C, Stroes ES, Soran H, et al. Issues affecting quality of life and disease burden in lipoprotein lipase deficiency (Lpld): first step towards a pro measure in Lpld [abstract]. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A707.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82.

World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(4):373–4.

Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62(1):102–11.

Acaster S. Patient-reported outcome and observer-reported outcome assessment in rare disease trials. Value Health. 2017;20(7):856–7.

Benjamin K, Vernon MK, Patrick DL, Perfetto E, Nestler-Parr S, Burke L. Patient-reported outcome and observer-reported outcome assessment in rare disease clinical trials: an ISPOR COA Emerging Good Practices Task Force Report. Value Health. 2017;20(7):838–55.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CB, JAR, TS, RJS, HD, and CJG made substantial contributions to conception and design and data interpretation. JS, KS, DCW, and EEK made substantial contributions to acquisition of data and interpretation of data. All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript or revising content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (No. RG1012C).

Conflict of interest

CJG has received fees/honorarium as a consultant to Regeneron; DCW has received fees/honorarium for providing expert opinion on pancreatic disease; JAR, TS, and CB are employees of Clinical Outcomes Solutions, which received funding from Regeneron; HD and RJS are employees of Regeneron and received salary and stocks/stock options; KLS received compensation for patient recruitment for Regeneron; and JAS and EEK have declared no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (IRB) (3500 Fifth Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA; http://www.irb.pitt.edu). The IRB approved a waiver for the requirement to obtain informed consent to use protected health information to identify potential research subjects for recruitment purposes only, however all participants were then asked to provide informated consent prior to engaging in the study (IRB #: PRO16110537).

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Burbridge, C., Randall, J.A., Sanchez, R.J. et al. Symptoms and Dietary Impact in Hypertriglyceridemia-Associated Pancreatitis: Development and Content Validity of Two New Measures. PharmacoEconomics Open 4, 191–201 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-019-0155-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-019-0155-y