Abstract

Crafting social resources is a job crafting strategy that implies changing one’s social job resources to improve person-job fit and work-related well-being. Previous research has mostly assumed a resource-generating nature of crafting social resources and investigated the linear positive effects of this job crafting strategy on, for example, work engagement. Considering that crafting social resources can also be resource-consuming, in this paper, we referred to conservation of resources theory and resource allocation theory and proposed a curvilinear, U-shaped relationship between crafting social resources and work engagement. We further predicted that exhaustion would moderate this curvilinear relationship. To test our hypotheses, a two-wave study with 233 employees was conducted. Consistent with our assumptions, compared with a low or high level, a moderate (i.e., occasional) level of crafting social job resources was associated with a lower level of work engagement three months later. Furthermore, exhaustion acted as a moderator insomuch that a low level of exhaustion mitigated the detrimental effect of crafting social resources at a moderate level on work engagement. Accordingly, the findings showed that crafting social resources is not always beneficial and can impair employees’ work engagement, especially for exhausted employees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The changing nature of work involves new flexible working arrangements, for instance flexible working hours. The resulting advantages of these new working arrangements (e.g., higher job autonomy) are often accompanied by negative effects for employees (e.g., less social contact with colleagues). A lack of direct contact and exchanges at work can be challenging in flexible working arrangements (Bartel et al., 2012). If employees receive fewer job resources, such as social support or feedback, then this has negative effects on work engagement (Demerouti et al., 2001) and employee health and well-being (e.g., Mathieu et al., 2019; Sparr & Sonnentag, 2008). However, employees can act proactively and initiate changes to job aspects, which is called job crafting (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). To foster the social job environment, employees can craft social resources (e.g., by asking colleagues for feedback or supervisors for coaching; Tims & Bakker, 2010). This job crafting strategy enables the development of a resourceful work environment (Tims et al., 2013) that – according to conservation of resources theory (COR; Hobfoll, 1989) – can result in gaining additional resources at work which enhances employees’ well-being and motivational outcomes such as work engagement.

Despite often confirmed positive effects (see Rudolph et al., 2017 for a meta-analysis), job crafting studies have also indicated that self-initiated changes in one’s job are not always beneficial for employees (e.g., Dubbelt et al., 2019; Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019). Crafting social resources can be resource-consuming as it is a form of proactive behavior at work and requires effort, resources and energy (Grant & Parker, 2009). Particularly, this job crafting strategy is resource consuming because changes to one’s job involves also others at work. For example, asking others for feedback (as one example of crafting social resources) can consume time and cognitive or emotional resources (Sung et al., 2020). Due to a limited pool of resources for employees (Kanfer & Ackerman, 1989), the resources devoted to crafting social resources are no longer available for ongoing work tasks or activities. The resulting shift in resources may change the focus on work tasks that, in turn, could impair employees’ work engagement.

Beyond the often confirmed linear effects of crafting social resources, we have been inspired by a study of nonlinear crafting’ effects (Dierdorff & Jensen, 2018) and, in this paper, assume a curvilinear relationship in which crafting social resources at a moderate (i.e., occasional) level (compared to a low and high level) is detrimental to work engagement. We argue that engaging in crafting social resources at a moderate level requires resources that are not available for the execution of regular or ongoing work tasks, which can be demotivating. In contrast, although employees need to invest more resources for crafting social resources at a high level, they may have developed routines in crafting social resources (i.e., they do this often) such that the amount of resources required for crafting social resources decreases (Kanfer & Ackerman, 1989). As a result, we assume that crafting social resources at a high level does not devote as many resources (compared to a moderate level) insomuch that employees are likely to focus on their ongoing work tasks while benefiting from their crafting’ achievements which will increase their work engagement.

We further consider exhaustion as a personal constraining energetic state (Lazazzara et al., 2020) that can influence the proposed relationship between crafting social resources and employees’ work engagement. Exhaustion refers to a subjective feeling of being overextended and depleted by constantly dealing with highly arousing situations (Maslach et al., 2001). Exhausted employees have fewer resources available (Maslach et al., 2001) in an already limited resource pool and are according to COR theory vulnerable to resource loss (Hobfoll, 2001). Thus, if exhausted employees craft social resources at a moderate level, they are less likely to focus on ongoing work tasks due to a resource shift, which can reduce their work engagement. Conversely, the availability of greater resources a) reduces the vulnerability when suffering a resource loss and b) may allow more efficient resource allocation at work, which, in turn, may prevent the detrimental effects of crafting social resources at a moderate level on work engagement.

Overall, we expand the literature by examining 1) a curvilinear effect of crafting social resources on work engagement and 2) the role of exhaustion in moderating this relationship. Thereby, we combine COR theory with resource allocation theory to show that employees’ well-being (i.e., work engagement) can benefit from an effective resource management while crafting social resources. Third, we use a sample of employees with flexible working hours. Since these employees are flexible in scheduling their working time, they may be missing social interactions through less overlap with the working hours of their colleagues or supervisors. Crafting social resources can be seen as a strategy to continue to provide social resources at work for employees with flexible working hours. Therefore, it is important to understand the impact of crafting social resources on work engagement among these employees.

Theory and Hypotheses

Crafting Social Resources as a Component of Resource-Oriented Job Crafting

Crafting social resources (i.e., increasing social resources) is a job crafting strategy and refers to self-initiated changes in (social) job resources, such as seeking social support, supervisor coaching, and colleagues’ feedback or advice (Tims et al., 2012). Job crafters – that is, employees who engage in job crafting – seek to expand (social) job resources, for example, by involving others at work (e.g., colleagues and supervisors) to obtain information about themselves and their work behavior. For instance, employees with flexible working hours can seek advice from colleagues for an upcoming task or ask their supervisors if they are satisfied with their performance. Therefore, crafting social resources impacts social aspects at work and may facilitate improved interactions (e.g., an open feedback culture). Crafting social resources is a form of resource-oriented job crafting and fits into the job crafting conceptualization of Tims et al. (2012), who defined job crafting as employees’ changes to balance job demands and job resources with their abilities and needs (Tims et al., 2012). In addition to crafting social resources, within this conceptualization, job crafters can also focus on crafting structural resources (e.g., deciding for themselves regarding how to do things), crafting challenging demands (e.g., doing extra tasks at work) and crafting hindering demands (e.g., avoiding contact with emotional or stressful colleagues; Tims et al., 2012). Given the significance of social job resources, especially for our sample of employees with flexible working hours, and their positive effects on work-related well-being (Hobfoll et al., 2018), in this study, we focus on crafting social resources as a component of resource-oriented job crafting.

Crafting Social Resources and Work Engagement

Work engagement is defined as a motivating, fulfilling, work-related state of mind characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Employees with a high level of work engagement experience high levels of energy (vigor), feel inspiration in their work (dedication) and fully concentrate on their work (absorption). Work engagement as an indicator of occupational well-being (Bakker et al., 2008) can be seen as an important outcome of job resources (e.g., Demerouti et al., 2001). Resources at work have both intrinsic and extrinsic motivational potential by providing not only learning and personal development but also information for goal achievement (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). Thus, a resourceful work environment encourages employees to be engaged at work (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007).

According to conservation of resources theory (COR; Hobfoll, 1989), employees strive to maintain or aggregate resources at work to protect valued and existing resources to cope with threatening situations to their (work-related) well-being (Hobfoll, 1989). By crafting social resources, employees endeavor to mobilize (social) job resources, which, in turn, can expand their resource pool at work. As employees with flexible working hours have less possibilities to interact with colleagues or supervisors at work (Kattenbach et al., 2010), these employees can actively seek to obtain social resources, like feedback or advice. Due to this increase in resources, employees possess instrumental means and are intrinsically motivated, which, in turn, enhances the level of work engagement (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). For example, by asking supervisors for feedback on a completed task, employees receive information about their work behavior that they can use for future work tasks and their personal development at work. Many studies have shown that crafting social resources is positively associated with work engagement (e.g., Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019; Rudolph et al., 2017). We therefore propose the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 1: Crafting social resources is positively (linearly) related to work engagement.

The Different Levels of Crafting Social Resources and Work Engagement

Previous research has predominantly focused on the resource-generating function of crafting social resources and its positive association with work engagement. However, little consideration has been given to the resource-consuming nature (Wang & Lau, 2021) of crafting social resources. Recent research has suggested that crafting social resources requires self-regulatory activities for which energy and resources are needed (Bakker & Oerlemans, 2019). In particular, crafting social resources, in which others at work are involved (e.g., asking colleagues for advice), can require employees’ resources. Not only the enaction of crafting social resources (Wang & Lau, 2021) but also the goal-directed process of being proactive consumes employees’ resources (Parker et al., 2010). This can have detrimental effects on work engagement for the following reason:

Following resource allocation theory (Kanfer & Ackerman, 1989), to complete different tasks at work, engage in social activities, or interact with customers (i.e., regular work tasks), employees have a limited resource pool available. As resources (e.g., cognitive or time resources) are allocated toward performing one task or action at a time, fewer resources will be available for ongoing work tasks or actions when engaging in new actions. Crafting social resources as a job crafting strategy goes beyond one’s formal job description (Berg et al., 2010b) and does not directly lead to goal achievement; therefore, it is likely that additional resources will have to be devoted to it. Thus, the resources needed for crafting social resources may then be missing for the execution of ongoing work tasks or activities that cannot be done as usual. This resource shift may decrease employees’ work engagement.

Indeed, there is first evidence that crafting social resources is not always positively related to work engagement (e.g., Harju et al., 2016; Van Wingerden et al., 2017). There is a possible trade-off in which the effects of crafting social resources range from beneficial to detrimental (Dierdorff & Jensen, 2018). As the trade-off is not necessarily linear in nature, we propose that crafting social resources is nonlinearly associated with work engagement; that is, crafting social resources may have different effects on work engagement depending on the intensity of this activity. First, we assume that a low level of crafting social resources (e.g., employees do not or only minimally ask others for feedback or advice) requires few resources. Thus, employees do not have to shift their resources at work in favor of crafting social resources, which, consequently, does not impair their work engagement. However, a low level of crafting social resources does not allow employees to benefit from the increase in job resources triggered by crafting social resources, which would improve the level of work engagement (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). In sum, a low level of crafting social resources requires few resources but simultaneously generates few resources such that it is neither beneficial nor detrimental for work engagement.

Second, we presume that at a moderate (i.e., occasional) level of crafting social resources (e.g., employees occasionally ask others for feedback or advice), employees invest a considerable amount of resources. Due to a limited pool of resources (Kanfer & Ackerman, 1989), the consumed resources for crafting social resources at a moderate level are no longer available for ongoing or regular tasks such that employees allocate their attentional focus less often to their work tasks or other activities. This can be reflected in lower work engagement. Furthermore, if employees craft their social resources at a moderate level, then they do it only occasionally and, in turn, may not be familiar with the self-initiated actions. For example, they may be somewhat unsure of how to ask for feedback. However, the amount of resources demanded for crafting social resources can be reduced with practice (Kanfer & Ackerman, 1989), which only occurs at a high but not at a moderate level. Repeated resource consumption for crafting social resources at a moderate level and the associated resource shifts from ongoing work tasks and activities can eventually decrease employees’ work engagement.

Third, we suppose that at a high level of crafting social resources (e.g., employees often ask others for feedback or advice), employees do not invest as many resources in these actions compared to a moderate level. This is counterintuitive at first sight as one might assume that a high level of crafting social resources requires a great deal of resources that are drawn from those available to perform regular work tasks or activities. However, although many resources are consumed at a high level of crafting social resources, employees are likely to be familiar with these actions and can therefore apply them more experienced. Drawing on resource allocation theory, the amount of resources needed for a particular action (e.g., crafting social resources) decreases with practice (Kanfer & Ackerman, 1989). That is, we assume that by crafting social resources at a high level, employees are practiced and know how to craft social resources (e.g., being familiar with how to ask for feedback). Additionally, crafting social resources at a high level might be visible to others at work, as they are often included in these actions (e.g., being asked for feedback). In this case, it may be easier for job crafters to actually obtain the intended resources (e.g., feedback) which positively enhance their work engagement (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). To sum up, employees, who craft social resources at a high level, are less likely to face the problem of devoting resources to crafting social resources that are intended for ongoing work tasks since they are experienced and familiar with crafting strategies.

However, we assume that compared with a low or high level, a moderate level of crafting social resources can be detrimental to work engagement through an increased resource allocation for crafting social resources. Therefore, we propose a curvilinear (i.e., a U-shaped) relationship between crafting social resources and work engagement in the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 2: Crafting social resources is curvilinearly related to work engagement such that the curve inflects toward negative effects of work engagement at a moderate level of crafting social resources.

The Moderating Role of Exhaustion

Recent research has suggested that the link between job crafting strategies (e.g., crafting social resources) and job crafting outcomes (e.g., work engagement) might depend on personal factors, which can be supportive or constraining (Lazazzara et al., 2020). In the following, we consider a possible constraining personal factor – employee’s level of exhaustion. Exhaustion describes individuals’ feelings as a consequence of intense physical, affective, and cognitive strain through a persistent exposure to job demands (Demerouti & Bakker, 2008). High levels of exhaustion are characterized by a depletion of activity and feelings of emptiness and overwhelm from work, which is associated, for instance, with depression, negative affect (Meier & Kim, 2022) or absenteeism (e.g., Peterson et al., 2008).

In line with this definition, employees who experience high levels of exhaustion perceive fewer resources at work (Maslach et al., 2001). Through their limited availability to resources, exhausted employees are more vulnerable to further resource loss and less capable of resource gain (Hobfoll, 2001). Combining this principle of COR theory with resource allocation theory, which is explained above, an exhausted employee’s resource pool is even more limited. If they additionally craft their social resources, then these employees allocate their attentional focus even less often to their ongoing work tasks. This, in turn, can decrease work engagement (Niessen et al., 2012). Furthermore, due to resource expenditure, especially by crafting social resources at a moderate level, exhausted employees can experience resource loss (Hobfoll, 1989), which negatively affects work engagement (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007).

In contrast, employees who experience a low level of exhaustion are not as limited in their amount of resources and are therefore not as vulnerable to resource loss compared to exhausted employees. Despite their resource allocation to crafting social resources, these employees have a certain amount of resources that they can still allocate to ongoing work tasks or activities. Thus, the probability of suffering a resource loss by crafting social resources at a moderate level declines with a low level of exhaustion and would thus not impair the level of work engagement.

-

Hypothesis 3: Exhaustion moderates the curvilinear effect of crafting social resources on work engagement such that in contexts of low exhaustion, the curvilinear effect is mitigated.

Method

Sample and Procedure

A total of 233 employees in Germany participated in a two-wave survey study with a time lag of three months between the points of measurement in 2015. The participants were recruited via a newsletter invitation from an online panel provider (Respondi AG). We selected only employees who determined their working time themselves (i.e., flexible working hours); at all points of measurement, participation was voluntary. The questionnaires were matched by using personal identification numbers. The study was approved by the university’s ethics commission (application number: 2015–06).

The first questionnaire was completed by 307 participants; 243 participants (79%) started the second survey. Participants who did not complete the second questionnaire completely (N = 10) were excluded from further analysis. Logistic regressions were used to predict drop-outs at T2 by using age, gender, employment status, and all the study variables at T1. The drop-out analyses showed that no predictor was significant.

The final sample (N = 233) included 130 men (56%) and 103 women (44%), with ages ranging from 24 to 66 years (M = 41.72, SD = 10.05). The majority had at least a university degree (87%). Their average work time per week was 41.6 hours (SD = 6.59), and their job tenure averaged 18 years (SD = 12.13). Participants had a great influence on their working hours and worked in different sectors and industries, whereby the most represented were public service/administration (21%), manufacturing (16%), and information technology (IT) services/telecommunications (10%).

Measures

The study variables were assessed at both measurement points.

Crafting Social Resources

Crafting social resources was assessed with the German version subscale increasing social resources (Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2016) of the Job Crafting Scale (JCS; Tims et al., 2012). This subscale captures the extent to which employees increase social resources of their job (“I ask my supervisor to coach me”, “I ask whether my supervisor is satisfied with my work”, “I look to my supervisor for inspiration”, “I ask others for feedback on my job performance”, and “I ask colleagues for advice”). The participants were asked to rate all items on a 5-point rating scale from 1 (rarely/never) to 5 (very often/always). We used crafting social resources assessed at Time 1.

Work Engagement

Work engagement was measured by using the German short version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9; Schaufeli et al., 2006). The scale consists of nine items that cover the three aspects of work engagement, specifically, vigor (e.g., “I feel strong and vigorous”), dedication (e.g., “I am enthusiastic about my work”), and absorption (e.g., “I feel happy when I am working intensively”). The work engagement measure referred to the last three months, and responses were given on a 5-point rating scale (1 = rarely/never; 5 = very often/always). We used work engagement measured at Time 2.

Exhaustion

Exhaustion was assessed with the corresponding burnout dimension of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI; Demerouti et al., 2003). The subscale consists of eight items, of which four items are positively worded (e.g., “I feel totally fit when I am working”) and four are negatively worded (e.g., “There are days when I feel tired before I arrive at work”). Participants were asked to respond to the items with a 5-point rating scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). We used exhaustion assessed at Time 1.

Control Variable

We controlled for social support (assessed at T1) as an important social job resource that could contaminate the measure of crafting social resources. By including social support, we emphasized the distinction between crafting social resources as a strategy and the actual presence of social support. Social support was measured by using the German version (Stegmann et al., 2010) of the Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ; Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006). The scale includes six items (e.g., “I have the chance in my job to get to know other people”), which were rated on a 5-point rating scale that range from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree).

Analysis Strategy

All analyses were calculated with R Studio (RStudio Team, 2021). Initially, confirmatory factor analyses with robust maximum likelihood (MLR) were conducted. Next, hypotheses were tested with a hierarchical polynomial regression analysis. First, the linear effect of crafting social resources was entered, followed by the quadratic term. If the quadratic term of crafting social resources was significant, then this was an indication of the curvilinear relationship between crafting social resources and work engagement. This effect was also checked by including social support as a control variable. Moderation by exhaustion was tested for both the linear and quadratic terms for crafting social resources. If the interaction effect with the quadratic term of crafting social resources was still significant, then the moderation effect was confirmed. To reduce common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003) and to examine long-term effects, we separated the measurement points, which means that we used the independent variable and the moderator (i.e., crafting social resources and exhaustion) at T1 and the dependent variable (i.e., work engagement) at T2.

Results

Table 1 provides the means, standard deviations (SDs), reliabilities and correlations of the study variables. Social resources were crafted by 41% of the participants at a low level (N = 96), 39% (N = 90) at a moderate level, and 20% (N = 47) at a high level. A low level included the responses 1 and 2 (never and rarely), a moderate level included the 3 (occasional) and a high level included 4 and 5 (often and very often). Social support had significant associations with crafting social resources (r = .34; p < .001), exhaustion (r = −.31; p < .001), and work engagement (r = .44; p < .001).

As the study variables were mostly correlated (only crafting social resources and exhaustion were not correlated), we initially performed confirmatory factor analyses, which showed that all variables differed from one another. A four-factor model with crafting social resources, social support, exhaustion, and work engagement as single factors showed an acceptable model fit χ2 (340, N = 233) = 781.221, p < .001; CFI = .875; RMSEA = .075 (CI90 [.068, .081]); SRMR = .081). This model fit the data better that the following three models: a one-factor model; a two-factor model in which crafting social resources, social support and exhaustion were loaded onto the same factor next to work engagement; and a three-factor model in which crafting social resources and social support were loaded onto the same factor next to exhaustion and work engagement. Detailed findings are available from the first author.

Nonlinear Effects of Crafting Social Resources on Work Engagement

Table 2 shows the results of the linear and curvilinear effect of crafting social resources on work engagement. The results showed a significant positive linear effect on work engagement (b = .27, p < .001). Hypothesis 1 was confirmed. Upon inclusion of the quadratic term of crafting social resources in the model (step 2), the quadratic term explained a small but significant amount of variance in work engagement (ΔR2 = .02, p < .05). Thus, the quadratic term of crafting social resources had a significant effect on work engagement (b = .14, p < .05).

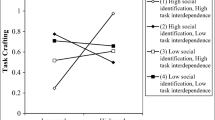

Figure 1 shows the curvilinear relationship between crafting social resources and work engagement. Thus, compared with a low and high level of crafting social resources, a moderate level was associated with a lower level of work engagement. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was confirmed.

The Moderating Effect of Exhaustion

Table 2 also provides the results regarding the role of exhaustion in moderating the curvilinear effect of crafting social resources on work engagement. To test the hypothesis, we included the interactions of the linear and quadratic terms of crafting social resources with exhaustion in the models (steps 5 and 6). The results showed that the quadratic term of crafting social resources and exhaustion moderated the effect on work engagement (b = .15, p < .05). Simple slope analysis revealed that for employees with a low level of exhaustion crafting social resources had no significant association with work engagement (b = .08, p = .29), but there was a curvilinear effect for employees with a high level of exhaustion (b = .31, p < .001). The forms of the exhaustion moderation are shown in Fig. 2 and indicate that a low level of exhaustion mitigated the detrimental effect of crafting social resources at a moderate level on work engagement. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was confirmed.

Additional Analyses

As there might be other forms of the relationship between crafting social resources and work engagement, we also tested for a cubic and exponential relationship. There were no significant effects and the model comparison indicated that the curvilinear relationship fit the data best.

Discussion

The present study sheds light on the resource-consuming nature of crafting social resources and investigates its nonlinear effect on work engagement. In addition to the positive linear effect, the results of the two-wave study revealed a curvilinear relationship between crafting social resources and work engagement three months later. Participants in our study who crafted their social resources at a moderate (i.e., occasional) level showed a lower level of work engagement three months later compared to participants who crafted social resources very intensively or not at all. Further, we found a moderating effect of exhaustion; that is, a low level of exhaustion buffered the detrimental effect of crafting social resources at a moderate level.

Crafting Social Resources and Work Engagement

In line with previous research and Hypothesis 1, we confirmed a positive linear association between crafting social resources and work engagement (e.g., Bakker & Oerlemans, 2019; Brenninkmeijer & Hekkert-Koning, 2015). Over and above previous studies, in which mostly short time intervals (e.g., day-level) or cross-sectional data were used, our results showed that the linear association can still be found three months later, indicating that the resource-generating nature of crafting social resources can last for some time. However, there might be limits. In some longitudinal studies there was no significant relation between crafting social resources and work engagement over time (e.g., six weeks, one or three years; Harju et al., 2016; van Wingerden et al., 2017b; Van Wingerden et al., 2017). Due to these ambiguous results, we assumed that there is a possible trade-off on which crafting social resources is no longer beneficial for employees’ work engagement.

As this trade-off is not necessarily linear in nature, we additionally investigated a curvilinear effect of crafting social resources on work engagement in our model. Including the quadratic term of crafting social resources had a better model fit that indicated a curvilinear relationship (U-shape) between the two variables. Consistent with our assumption, a moderate (i.e., occasional) level of crafting social resources had a detrimental effect on work engagement three months later. Our results suggest that crafting social resources at a moderate level compared to a low and high level seems to be more resource-consuming and may impair employees’ work engagement. There seems to be a resource conflict (Dierdorff & Jensen, 2018) between engaging in crafting social resources at a moderate level and efficient resource allocation to work tasks, resulting in a resource shift. However, we were not able to test whether or when such a resource shift could occur. This, and a change in the amount of perceived resources before and after assessing crafting social resources as mediators in the relationship between crafting social resources and work engagement should be addressed in future studies.

Consistent with our assumption, crafting social resources at a high level (compared to a moderate level) was beneficial for work engagement. We proposed that a high level of crafting social resources is more familiar to job crafters such that they are practiced and experienced, and therefore, the amount of resources needed for crafting decreases (Kanfer & Ackerman, 1989). In the future, the level of practice in crafting social resources should explicitly investigate, for example, since when or how often an employee crafts social resources or how familiar s/he feels with these actions. In this vein, two recently introduced constructs should also be considered. First, job crafting competencies describes a set of knowledge, skills, and abilities to craft one’s job to fulfill personal motives and needs (Bruning & Campion, 2022) such that a high level of crafting social resources may also mean to have specific capabilities to use different patterns of relevant information and skills (Bruning & Campion, 2022) for crafting social resources. Second, job crafting self-efficacy which refers to individual’s beliefs about the own capabilities to alter job demands and job resources to better fit with needs and preferences (Roczniewska et al., 2020). A high level of job crafting self-efficacy means that employees have the control to implement crafting social resources successfully.

The Moderating Role of Exhaustion

In this study, we found that exhaustion moderated the curvilinear relationship between crafting social resources and work engagement. Specifically, a low level of exhaustion buffered the detrimental effect of crafting social resources at a moderate level. That is, when employees experienced a low level of exhaustion, crafting social resources at a moderate level did not have a detrimental effect on their work engagement three months later. Rather, there was no association between the two variables. In contrast, the curvilinear relationship between crafting social resources and work engagement was more pronounced for employees with a high level of exhaustion. This is in line with our assumption that exhausted employees have limited resources (Maslach et al., 2001), even less than nonexhausted employees, that they can use at work. It seems that a high level of exhaustion may not allow employees to adequately manage their resources while crafting social resources (Lazazzara et al., 2020) such that the limited resources are probably not allocated efficiently (e.g., on regular work tasks).

Furthermore, our study results indicated that exhaustion does not influence whether employees engage in crafting social resources (there was no correlation between both variables). Recent research has suggested that on days when employees experience a high level of exhaustion, they craft more social resources (Breevaart & Tims, 2019). In contrast to the scholars’ assumption that exhausted employees are likely to invest a small number of available resources to enhance their resource pool by crafting social resources, our findings indicate that employees who are exhausted have no more energy to invest in building new resources. Potentially, both reactions are possible and counteract one another, which explains the null findings. Hence, we provide evidence for the timely question of under which conditions crafting bears costs for employees or organizations (Berg et al., 2010a).

Limitations and Future Research

In the following, we discuss the limitations of our study and provide suggestions for future research. First, as in previous studies (Breevaart & Tims, 2019; Demerouti & Peeters, 2018), only one job crafting strategy was investigated. Due to the significance of social job resources (Hobfoll et al., 2018) also for our target sample, we focused on crafting social resources. For the other crafting actions (e.g., crafting challenging demands), the possible resource conflict between engaging in crafting, resource allocation and the effects on work engagement could be different or stay away. Considering latest research on nonlinear crafting’ effects, future studies should focus on the interactions between different job crafting strategies. Recently, a cross-sectional study showed that, for example, crafting social resources combined with a high level of crafting hindering demands also had unfavorable effects on work engagement (Xanthopoulou & Stamovlasis, 2020). Overall, future studies examining nonlinear effects of job crafting strategies should also consider other indicators of employees’ health and well-being (e.g., positive affect or strain).

Second, we had a relatively selective sample, as it consisted of employees with a high academic degree and very flexible working hours. Although flexibility at work enables employees to craft their jobs (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001), if everybody at work uses this flexibility, then crafting social resources may be hindered. That is, if flexibility includes working whenever or wherever you want, colleagues do not meet at work or in the office, which may decrease the job crafter’s willingness to ask for feedback or coaching (i.e., crafting social resources). This could be a reason why employees craft social resources only at a moderate level because others at work are only occasionally available. In general, we do not know why participants crafted social resources at different levels and whether they felt comfortable with their level. Perhaps employees perceive boundary conditions that hinder them from crafting social resources at a higher level. While our results should be investigated with a broader sample and include crafting antecedents, our study provides first insides into crafting social resources of employees with flexible working hours. As the amount of employees with flexible working hours has increased in the last years (Piasna, 2018), it becomes more important to investigate outcomes of their crafting efforts.

Finally, the use of self-report measures did not inform us of whether and how intensive colleagues or supervisors perceive crafting social resources of job crafters. Although the visibility of crafting social resources at a high level could be advantageous, we cannot confirm this assumption within our data. Latest research showed that others at work (e.g., supervisors) observe crafting actions, evaluate and react to them (e.g., extent of supervisor support; Fong et al., 2020) which is likely to impact the job crafter (Tims et al., 2021). However, to date, it is not clear why this is the case. Following Tims and Parker’s (2020) conceptual model, future research should measure how others at work perceive and evaluate crafting of social resources of job crafters, which prosocial motive attribution (i.e., supportive vs. antagonistic) they make towards job crafters, and how they react towards the job crafter. If others at work are confused, for example, about job crafter’s occasional crafting actions, the job crafter is unlikely to receive sufficient feedback regarding his/her crafting behavior (Dierdorff & Jensen, 2018), which can impair job crafter’s work engagement. Moreover, future research should consider contextual factors that can play a role in how colleagues or supervisors respond to crafting social resources. To give an example: A colleague who experiences high workload is asked for feedback, but s/he is not able to react to the job crafter’s actions.Footnote 1 This allows a better understanding about the influence that individual crafting actions have on others at work. In sum, different levels of crafting social resources and their impact on the social work environment should be studied more extensively.

Practical Implications and Overall Conclusion

To keep up with rapid changes in the work environment and to gain a competitive advantage, organizations are dependent on employees to be engaged at work. This applies in particular to employees with flexible working hours, as their number increases due to the changes of the world of work. Work engagement represents an important indicator of occupational well-being (Bakker et al., 2008) and should therefore be increased in employees. Previous research demonstrated that crafting social resources promotes engaged employees (e.g., Rudolph et al., 2017). However, our study results have implications for the use of crafting social resources and its impact on work engagement as an indicator of occupational well-being.

First, organizations should provide employees with a work environment in which crafting social resources is possible and in which everyone can decide on their own level of crafting social resources. Organizations must ensure that job crafters experience working conditions that enable them to craft their social resources (e.g., job autonomy). Studies have shown that many job characteristics, such as job autonomy, task interdependence or skill variety (Rudolph et al., 2017; Zhang & Parker, 2019), are important conditions for crafting social resources. In a trust-based work environment, mistakes at work are seen as learning experiences, and employees are more encouraged to try new things (Wang et al., 2017), such as crafting social resources. Furthermore, job crafters supported by their organizations experience fewer barriers and are thus more successful in crafting social resources (Kim et al., 2018). In addition to a work environment that fosters crafting social resources, organizations should ensure that employees perceive a low level of exhaustion. Thereby, they can handle their amount of resources efficiently from which employees’ work engagement, and, in turn, their health and well-being would benefit.

Second, employees should be aware that different levels of crafting social resources can have different effects on their work engagement and health, which possibly depends on their available resources. In this regard, employees should be aware of their limited resource pool and know how many resources are still available to them. If they do not perceive their resources to be sufficient, then employees should focus on their current or ongoing work tasks (i.e., regarding their job description) and refrain from crafting social resources as an additional activity. From a broader perspective, a job crafting intervention can provide opportunities for improved awareness and for fostering an appropriate level of crafting social resources and other job crafting strategies. In most previous job crafting intervention studies, employees first learn about job crafting and reflect on their current job situation and available resources and demands at work (van Wingerden et al., 2017a). Afterward, employees must set goals aimed at job crafting strategies (e.g., crafting social resources) that should be implemented at certain times (e.g., 4 weeks). A meta-analysis has confirmed that job crafting interventions enhance not only job crafting but also work engagement (Oprea et al., 2019) and employees’ health (Gordon et al., 2018). However, building on our study results, in future job crafting interventions, employees should be aware of the boundaries of crafting social resources and their available resources (e.g., during goal setting). Moreover, in this context, employees should learn efficient resource management when they want to craft their social resources.

In conclusion, our study showed that different levels of crafting social resources have different effects on work engagement (i.e., occupational well-being). Specifically, a moderate level of crafting social resources is detrimental to work engagement three months later. This only applies to employees who are exhausted. Thus, our results are not meant to imply that only a high level of crafting social resources is beneficial. Rather, we emphasize that when employees engage in crafting social resources, their resource management could play an important role in the effects of crafting social resources on work engagement.

Notes

We thank an anonymous reviewer for this idea.

References

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

Bakker, A. B., & Oerlemans, W. G. M. (2019). Daily job crafting and momentary work engagement: A self-determination and self-regulation perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112, 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.12.005

Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress, 22(3), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802393649

Bartel, C. A., Wrzesniewski, A., & Wiesenfeld, B. M. (2012). Knowing where you stand: Physical isolation, perceived respect, and organizational identification among virtual employees. Organization Science, 23(3), 743–757. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0661

Berg, J. M., Grant, A. M., & Johnson, V. (2010a). When callings are calling: Crafting work and leisure in pursuit of unanswered occupational callings. Organization Science, 21(5), 973–994. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0497

Berg, J. M., Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2010b). Perceiving and responding to challenges in job crafting at different ranks: When proactivity requires adaptivity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(2–3), 158–186. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.645

Breevaart, K., & Tims, M. (2019). Crafting social resources on days when you are emotionally exhausted: The role of job insecurity. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(4), 806–824.

Brenninkmeijer, V., & Hekkert-Koning, M. (2015). To craft or not to craft: The relationships between regulatory focus, job crafting and work outcomes. The Career Development International, 20(2), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-12-2014-0162

Bruning, P. F., & Campion, M. A. (2022). Assessing job crafting competencies to predict tradeoffs between competing outcomes. Human Resource Management, 61(1), 91–116. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22081

Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2008). The Oldenburg burnout inventory: A good alternative to measure burnout and engagement. In J. R. B. Halbesleben (Ed.), Handbook of stress and burnout in health care (pp. 65–78). Nova Science Publishers Inc.

Demerouti, E., & Peeters, M. C. W. (2018). Transmission of reduction-oriented crafting among colleagues: A diary study on the moderating role of working conditions. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 91(2), 209–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12196

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Vardakou, I., & Kantas, A. (2003). The convergent validity of two burnout instruments: A multitrait-multimethod analysis. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1027//1015-5759.19.1.12

Dierdorff, E. C., & Jensen, J. M. (2018). Crafting in context: Exploring when job crafting is dysfunctional for performance effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(5), 463–477. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000295

Dubbelt, L., Demerouti, E., & Rispens, S. (2019). The value of job crafting for work engagement, task performance, and career satisfaction: Longitudinal and quasi-experimental evidence. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(3), 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1576632

Fong, C. Y. M., Tims, M., Khapova, S. N., & Beijer, S. (2020). Supervisor reactions to avoidance job crafting: The role of political skill and approach job crafting. Applied Psychology, 70(3), 1209–1241.

Gordon, H. J., Demerouti, E., Le Blanc, P. M., Bakker, A. B., Bipp, T., & Verhagen, M. A. M. T. (2018). Individual job redesign: Job crafting interventions in healthcare. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 104, 98–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.07.002

Grant, A. M., & Parker, S. K. (2009). Redesigning work design theories: The rise of relational and proactive perspectives. The Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 317–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520903047327

Harju, L. K., Hakanen, J. J., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2016). Can job crafting reduce job boredom and increase work engagement? A three-year cross-lagged panel study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 95–96, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.07.001

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 50(3), 337–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Kanfer, R., & Ackerman, P. L. (1989). Motivation and cognitive abilities: An integrative/aptitude-treatment interaction approach to skill acquisition. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(4), 657–690. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.74.4.657

Kattenbach, R., Demerouti, E., & Nachreiner, F. (2010). Flexible working times: Effects on employees’ exhaustion, work-nonwork conflict and job performance. The Career Development International, 15(3), 279–295. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620431011053749

Kim, H., Im, J., Qu, H., & NamKoong, J. (2018). Antecedent and consequences of job crafting: An organizational level approach. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(3), 1863–1881. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-01-2017-0040

Lazazzara, A., Tims, M., & de Gennaro, D. (2020). The process of reinventing a job: A meta–synthesis of qualitative job crafting research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 116, 103267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.01.001

Lichtenthaler, P. W., & Fischbach, A. (2016). The conceptualization and measurement of job crafting validation of a German version of the job crafting scale. Zeitschrift für Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie, 60(4), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1026/0932-4089/a000219

Lichtenthaler, P. W., & Fischbach, A. (2019). A meta-analysis on promotion- and prevention-focused job crafting. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(1), 30–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2018.1527767

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job Burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

Mathieu, M., Eschleman, K. J., & Cheng, D. (2019). Meta-analytic and multiwave comparison of emotional support and instrumental support in the workplace. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(3), 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000135

Meier, S. T., & Kim, S. (2022). Meta-regression analyses of relationships between burnout and depression with sampling and measurement methodological moderators. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(2), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000273

Morgeson, F. P., & Humphrey, S. E. (2006). The work design questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1321–1339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1321

Niessen, C., Sonnentag, S., & Sach, F. (2012). Thriving at work—A diary study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(4), 468–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.763

Oprea, B. T., Barzin, L., Vîrgă, D., Iliescu, D., & Rusu, A. (2019). Effectiveness of job crafting interventions: A meta-analysis and utility analysis. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(6), 723–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1646728

Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management, 36(4), 827–856. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310363732

Peterson, U., Demerouti, E., Bergström, G., Åsberg, M., & Nygren, Å. (2008). Work characteristics and sickness absence in burnout and nonburnout groups: A study of Swedish health care workers. International Journal of Stress Management, 15(2), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.15.2.153

Piasna, A. (2018). Scheduled to work hard: The relationship between non-standard working hours and work intensity among European workers (2005–2015). Human Resource Management Journal, 28(1), 167–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12171

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Roczniewska, M., Rogala, A., Puchalska-Kaminska, M., Cieślak, R., & Retowski, S. (2020). I believe I can craft! Introducing job crafting self-efficacy scale (JCSES). PLoS One, 15(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237250

RStudio Team (2021). RStudio: Integrated Development for R (1.1.456). RStudio, Inc.

Rudolph, C. W., Katz, I. M., Lavigne, K. N., & Zacher, H. (2017). Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102, 112–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.05.008

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.248

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 3(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-National Study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

Sparr, J. L., & Sonnentag, S. (2008). Feedback environment and well-being at work: The mediating role of personal control and feelings of helplessness. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 17(3), 388–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320802077146

Stegmann, S., van Dick, R., Ullrich, J., Charalambous, J., Menzel, B., Egold, N., & Wu, T. T.-C. (2010). Der Work Design Questionnaire: Vorstellung und erste Validierung einer Deutschen Version = The Work Design Questionnaire— Introduction and Validation of a German version. Zeitschrift für Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie, 54(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1026/0932-4089/a000002

Sung, S. Y., Rhee, Y. W., Lee, J. E., & Choi, J. N. (2020). Dual pathways of emotional competence towards incremental and radical creativity: Resource caravans through feedback-seeking frequency and breadth. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(3), 421–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2020.1718654

Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual jobredesign. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v36i2.841

Tims, M., & Parker, S. K. (2020). How coworkers attribute, react to, and shape job crafting. Organizational Psychology Review, 10(1), 29–54.

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2013). The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(2), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032141

Tims, M., Twemlow, M., & Fong, C. Y. M. (2021). A state-of-the-art overview of job-crafting research: Current trends and future research directions. Career Development International., 27(1), 54–78. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-08-2021-0216

Van Wingerden, J., Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2017). The impact of personal resources and job crafting interventions on work engagement and performance. Human Resource Management, 56(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21758

van Wingerden, J., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2017a). Fostering employee well-being via a job crafting intervention. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 100, 164–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.03.008

van Wingerden, J., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2017b). The longitudinal impact of a job crafting intervention. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(1), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2016.1224233

Wang, Y., & Lau, D. C. (2021). How and why job crafting influences creative performance? A resource allocation explanation of the curvilinear moderated relations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1–27.

Wang, H., Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2017). A review of job-crafting research: The role of leader behaviors in cultivating successful job crafters. In S. K. Parker & UK Bindl (Eds.), Proactivity at work (pp. 95–122). Taylor & Francis.

Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179–201.

Xanthopoulou, D., & Stamovlasis, D. (2020). Job crafting and work engagement: Can their relationship be explained by a catastrophe model? Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 24(3), 305–326.

Zhang, F., & Parker, S. K. (2019). Reorienting job crafting research: A hierarchical structure of job crafting concepts and integrative review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(2), 126–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2332

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was supported by a grant of the German Ministry of Research and Education (BMBF, grant number: 01FK13028).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Elisa Lopper: Conceptualization; formal analysis; data curation; software; methodology; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review & editing.

Jan Dettmers: Funding acquisition; project administration; resources; writing – review & editing.

Annekatrin Hoppe: Funding acquisition; project administration; resources; supervision; writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The project was authorized by the ethics committee of the Department of Psychology of the Humboldt University Berlin (application number: 2015–06).

Consent to Participate

Every participant gave their consent to participate.

Consent for Publication

Every participant gave their consent for publication. Participants could contact the project staff to withdraw from the study after participation.

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

The authors have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Research data for this article: Due to the sensitive nature of the questions asked in this study, the survey respondents were assured that the raw data would remain confidential and would not be shared.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lopper, E., Dettmers, J. & Hoppe, A. Examining Nonlinear Effects of Crafting Social Resources on Work Engagement – the Moderating Role of Exhaustion. Occup Health Sci 6, 585–604 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-022-00124-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-022-00124-w