Abstract

Management theory and practice are facing unprecedented challenges posed by the amount of suffering induced and caused by the recent financial crisis, increasing social inequity, the worldwide spread of terrorism, and the consequences of climate change (Hart 2005, p. 61; Prahalad 2005; Senge 2008). Spiritual figures such as the Dalai Lama and Pope Benedict XVI have repeatedly highlighted the central role of compassion to alleviate the pain caused by these crises. Drawing on ancient spiritual teaching about empathy and the more recent insights regarding the relevance of emotions (e.g. emotional intelligence), emotion-centric perspectives of management have been advocated more strongly in the very recent past (Brockner and Higgins Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 86(1):35-66 2001; Cooper and Sawaf 1996; Mayer et al. Annual Review of Psychology 59:507-536 2008). So far, however, compassion related concepts have played a marginal role within management research. Dutton et al.’s Administrative Science Quarterly 51(1):59-96(2006) seminal paper offers a much needed perspective as it allows to conceptualize compassion as an organizational focal point.

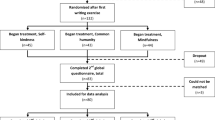

In this paper, I set out to examine boundaries to the general applicability of compassion organizing theory. Istart by examining the assumptions regarding the human capacity for compassion presented by Dutton et al. Administrative Science Quarterly 51(1):59-96(2006). I further develop a set of boundary conditions of individual level compassion capability, a precondition for compassion organizing. I then develop a typology of compassion capability proposing four archetypes of individual level compassion capability, and transpose the insights generated onto a typology of organizing modes. This typology allows distinguishing the various modes of compassion organizing, and helps identifying the structures and mechanisms that undermine compassion organizing. As such, Ihope to contribute to a better understanding of the potential for compassion organizing in theory and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Management theory and practice are facing unprecedented challenges posed by the amount of suffering induced and caused by the recent financial crisis, increasing social inequity, the worldwide spread of terrorism, and the consequences of climate change (Hart 2005, p. 61; Prahalad 2005; Senge 2008). Spiritual figures such as the Dalai Lama and Pope Benedict XVI have repeatedly highlighted the central role of compassion to alleviate the pain caused by these crises. Drawing on ancient spiritual teaching about empathy and the more recent insights regarding the relevance of emotions (e.g. emotional intelligence), emotion-centric perspectives of management have been advocated more strongly in the very recent past (Brockner and Higgins 2001; Cooper and Sawaf 1996; Mayer et al. 2008). So far, however, compassion related concepts have played a marginal role within management research. Dutton et al. (2006) state that the process of organizing to alleviate pain is generally not well understood. They further argue that organizational researchers have rarely focused on how and why some patterns of organizing compassion emerge and work more effectively than others (Dutton et al. 2006, p. 59). Dutton et al.’s (2006) seminal paper offers a much needed perspective as it allows to conceptualize compassion as an organizational focal point. In a time when expectations for businesses to compassion organize have exponentially increased (Jackson and Nelson 2004; Margolis and Walsh 2003), such theory is critical to support organizational transformation (see for example efforts to establish for – benefit organizations). While a theoretical perspective based on a case study benefits from the accuracy and simplicity generated (such as in Dutton et al. 2006), there remain questions as to its generality (Sutton and Staw 1995; Weick 1979). Since such theories could provide substantial theoretical and practical benefit on how to deal with these major crises, their generality needs to be further examined (Weick 1995).

In this paper, we set out to examine boundaries to the general applicability of compassion organizing theory. We start by examining the assumptions regarding the human capacity for compassion presented by Dutton et al. (2006). We further develop a set of boundary conditions of individual level compassion capability, a precondition for compassion organizing. We then develop a typology of compassion capability proposing four archetypes of individual level compassion capability, and transpose the insights generated onto a typology of organizing modes. This typology allows distinguishing the various modes of compassion organizing, and helps identifying the structures and mechanisms that undermine compassion organizing. As such, we hope to contribute to a better understanding of the potential for compassion organizing in theory and practice.

Compassion Capability as Prerequisite of Compassion Organizing

Compassion organizing is defined as collective response to a particular incident of human suffering that entails the coordination of individual compassion in a particular organizational context (Dutton et al. 2006, p.61). This definition presumes an individual’s capability to be compassionate, which in turn is defined as the ability to notice, feel, and respond to another’s suffering (p.60). Compassion capability specifically requires the ability for an individual to notice the suffering of another, feel inherently other regarding concern, and behave with the intention to ease the other party’s suffering (Dutton et al. 2006, p.61). Despite a lack of focused attention within management research, compassion and closely related constructs of care, sympathy, empathy, and concern have received attention as distinct human capacity supporting our social and relational nature in a variety of other disciplines (e.g. Batson 1990; Gilbert 2005; Titmuss 2001). While often not stated explicitly there exist a variety of assumptions about the nature of compassion capability. In the developing research on compassion within organizational contexts it is assumed e.g. that it is an innate human instinct (Dutton et al. 2006). This account is largely supported by anthropologists, biologist and evolutionary psychologists (Lawrence 2007, 2010). However, as Batson (1990) argues a large number of psychologists and sociologists deny the possibility of compassion as a true other regarding concern, an account that economists subscribe to as well (see notion of homo oeconomicus). As such compassion with regard to authentic other regarding concern becomes mere fiction.

In the following, we wish to scope out the basic assumptions regarding compassion capability as either an unbounded or a bounded concept. While there are different scientific accounts on compassion, involving the notion of sympathy, empathy or concern, we distill their perspective on the generality of compassion capability as a basis for the further examinations of boundaries to compassion organizing.

Narratives of Unbounded Compassion Capability

Compassion Capability as Norm/Default

Starting from Aristotle’s observations that we are social animals, human nature is considered to encompass a capacity for care and concern of the other (Batson 1990). As Adam Smith wrote, man is motivated by sympathy as well as by self-interest. He suggests that “there are evidently some principles in nature, which interest him in the fortune of others..” One such principle is “pity or compassion, the emotion we feel for the misery of others…”(Smith 1759, 1.1.1.1). Darwin (1909b) similarly observed that there must be an innate drive for compassionate behavior: “Under circumstances of extreme peril, as during a fire, when a man endeavors to save a fellow-creature without a moment’s hesitation, he can hardly feel pleasure; and still less has the time to reflect on the dissatisfaction which he might subsequently experience if he did not make the attempt. Should he afterwards reflect over his own conduct, he would feel that there lies within him an impulsive power widely different from a search after pleasure or happiness; and this seems to be the deeply planted social instinct” (p. 122).

The account of compassion capability as a norm has received further support from evolutionary biologists and anthropologists since, who argue that the ability for care and compassion allowed the human species to survive and thrive (see Diamond 1992; Lawrence 2010). Especially the relationship between mother and infant prescribes a relationship of care and concern unique to humans, who mature comparatively slow and need the protection of kin. It is further argued that this innate capacity of females to bond via compassion is extended to the nuclear family by partner selection, and then onto the tribe and possibly to humanity at large (Darwin 1909a; Lawrence 2010).

Compassion Capability as Universal Potential

A different perspective is presented in theological and spiritual traditions (Smith 2002; Thupten 2005), in that compassion capability is viewed as an aspiration with universal potential. Accordingly the existence of pain is conditio humana, and compassion the potential remedy. This perspective is most prevalent in some of the Eastern spiritual tradition but also has firm roots in Western theology. The suffering of Christ, for example, is the ultimate act of compassion which wins his followers the right to eternal life. Whereas this perspective is mostly expressed in spiritual and theological traditions, these perspectives have permeated culture and tradition in many societies. As Wuthnow (1991) suggests, the early educators in the United States placed compassion in the center of their educational mission, assuming that it was crucial to the development of a better society. Compassion as such is not viewed as innate, but something that needs to be nurtured and developed. However, compassion capability is assumed to have universal potential, and reigns as a guiding principle on how to live life as an individual and within organizational contexts.

Narratives of Bounded Compassion Capability

Compassion Capability as Positive Deviance

Another perspective views compassion as a possibility. As Wilson (1993) suggests, sympathy or compassion is a motive. As a consequence this perspective renders compassion capability much more exclusive in that it does not describe a default but rather a deviation from the norm.

In the organizational level research, such a perspective is echoed to the extent that explicitly or implicitly compassion among many other features in organizational life (such as respect, forgiveness and virtue) is considered a rare circumstance. It is argued that compassionate behavior is an “intentional behavior that departs from the norms of a referent group in honorable ways” (Spreitzer and Sonenshein 2004, p. 832).

Compassion Capability as Fiction

The social sciences, including economics, psychology, sociology and political science largely assume that true altruistic, other regarding concerns do not exist (see e.g. Batson 1990; Henrich et al. 2001; Lawrence and Nohria 2002b). In this perspective compassion capability is socially constructed behavior, not innate, but learned through socialization. Batson (1990) lists three pervasive assumptions about the egoistical nature of human concern, care and compassion, which support the perspective that compassion capability as defined by Dutton et al. (2006) is fiction. The first reason for compassion is aversive arousal reduction, which means that people act in compassionate ways only to reduce their own suffering induced by watching the other suffer. The second reason humans act compassionately is to avoid empathy-specific punishment. It is argued that we wish to avoid social ostracism, which we understand could arise when not helping a person in need. The third reason we act compassionately can be traced to empathy specific rewards we receive from helping, not from being truly concerned with the fate of the other. In that understanding compassion is born out of egoistic self-preservation needs, which presents severe boundaries to compassion organizing, as compassion capability is considered non-existent.

While these perspectives are certainly not mutually exclusive they are clearly distinct. In turn, we will now draw on the evidence presented for each of these perspectives to explore the individual level boundaries to compassion capability.

Exploring the Boundaries of Compassion Capability

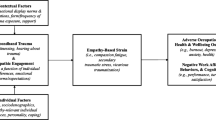

As Dutton et al. (2006) suggest compassion organizing is a recurring process which includes two conceptually differing stages: compassion activation and compassion mobilization. The compassion activation stage encompasses the noticing and feeling of another’s suffering, while the compassion mobilization stage refers to the behavioral response to said suffering. Based on this understanding, we suggest exploring the potential boundaries to compassion organizing along the dimension of compassion activation, which includes the cognitive capacity to notice another’s suffering (1), and the emotional capacity to feel another’s suffering (2). We further propose to independently analyze the compassion mobilization stage, which refers to the behavioral capacity to respond to another’s person suffering (3). As various scholars argue (Alzola 2008; Blair et al. 2005; Lawrence 2010) there are dispositional and situational limits to each of these capabilities, which could cause meaningfully different managerial implications, e.g. in terms of selection and training. We will in turn analyze where such dispositional and situational limits could persist.

Boundaries of Compassion Activation

Dispositional Cognitive Boundaries to Compassion Activation

For the notion of compassion organizing to be relevant an individual must be capable to notice another person’s suffering. Kanner (1968) discovered that there is a group of individuals, which is incapable of noticing and interpreting the emotions of people that surround them. He labeled this syndrome autism, which refers to the consequence of such inability, extreme aloneness (Lehrer 2009). While scholars debate whether the causes are purely genetic, environmental, or a combination thereof, there is agreement that autism is caused by a lack of neural development in early childhood. Rizzolatti et al. (2000), Rizzolatti et al. 2001) for example, suggest that the cortex of people with autism does not develop and connect a small cluster of cells, called ‘mirror neurons’. According to them, these cells allow us to reflect expressions of others inside our brain; people suffering from autism, however, are unable to recognize the mental and emotional states of others. This in turn renders them unable to express compassion towards others, impairs their ability to make friends, and as a consequence they become outsiders (Health 2010).

Autism is considered a spectrum disorder, which means that there are lighter versions of autism called high-functioning autism or Asperger Syndrome (Baron-Cohen 1995; Baron-Cohen et al. 2001) and more severe forms referred to as Autistic disorder, sometimes called autism or classical ASD (Health 2010). It is estimated that as many as 1 in 150 people are autistic, with males being four times more likely to be diagnosed with Autism. This adds up to almost 1.5 million people in the United States alone. Government statistics even suggest that the rate of autism is rising 10–17% annually(Rice 2009). Whatever the reason for such increases are (better and more pervasive diagnosis, environmental factors, etc.), the limit for compassion organizing is real. While the severe forms of autism don’t seem to be treatable, the lighter forms allow for some interventions that can ameliorate the capacity to cognitively notice another person’s suffering(Baron-Cohen et al. 2001), by using alternative areas of the brain that can compensate for the lack of mirror neurons (e.g. Memory).

-

Proposition 1a: Autism syndroms represent a dispositional, cognitive boundary to compassion activation.

Situational Cognitive Boundaries to Compassion Activation

While most people do not suffer from dispositional cognitive disorders such as autism, decades of psychological research have found that humans are limited information processors (Kahneman et al. 1982; Williamson 1979). Along these lines, experiments have shown that cognitive overload establishes information processing problems which require filtering and other heuristics (Kahneman et al. 1982). Such cognitive overload represents a situational limit to compassion activation, as it potentially prevents people from noticing another person’s suffering. According to Waddington (1996) and Wurman (1990) this is a rather common phenomenon. Kirsh (2000) further states that cognitive overload is particularly virulent in the workplace as many studies show that manager and employees suffer from consistent stress because of too much information supply, too much information demand, and the need to deal with multi-tasking and interruption.

-

Proposition 1b: Cognitive overload represents a situational, cognitive, individual-level boundary to compassion activation.

Dispositional Emotional Boundary to Compassion Activation

Neuroscientists and evolutionary biologists argue that emotions are central to our decision making ability (Blair et al. 2005; Damasio 2005). The notion of compassion capability refers to this centrality, however, there seem to be two general cases in which the capacity to feel another person’s suffering is limited in a dispositional manner. According to neuroscientists (LeDoux 1996), the first case is caused by insufficiencies of the amygdala (which generates emotions), and the second with insufficiencies in the prefrontal cortex (which processes such information) (see also Lawrence 2010).

The first boundary to compassion capability attributed to insufficiencies of the amygdala is termed psychopathy. Researchers have identified psychopaths, whom biologists and economists call “free-riders”, sociologists “sociopaths” or “loose individuals (Nisbet 2003) as people with a genetic defect (Weber et al. 2008). They are incapable of empathy and compassion and have no skill set of conscience or morality (Cleckley 1982). Hare (1999) describes psychopaths as “social predators who charm, manipulate, and ruthlessly plow their way through life, leaving a broad trail of broken hearts, shattered expectations, and empty wallets. Completely lacking in conscience and in feelings for others, they selfishly take what they want and do as they please, violating social norms and expectations without the slightest sense of guilt or regret ( p. XI).” They have “an insatiable appetite for power and control (p. 218)” combined with “a deeply disturbing inability to care about the pain and suffering experienced by others—in short, a complete lack of empathy (p.6).”

It is argued that a significant portion of the population is indeed unable to generate feelings. Anthropologists and evolutionary biologists argue that previous hominoids such as the homo habilines lacked such abilities, and that psychopathy could be a leftover of an evolutionary past (Lawrence 2010; Rizzolatti 1998). In fact, it is estimated that about 1% of the population does lack that ability to empathize and generate feeling, despite the ability to notice suffering in others (Hare 1999; Neumann and Hare 2008). Again, this insufficiency is more common among men (Blair et al. 2005). Hare estimates—conservatively, he insists—that “there are at least 2 million psychopaths in North America; the citizens of New York City have as many as 100,000 psychopaths among them (p.1-2).” Babiak and Hare (2006) even argue that many of these psychopaths are able to gain influence and power and that the current corporate environment allows them to do so effectively (see for a similar argument Bakan 2004; Sutton 2007). In fact, historians have made the argument that many examples of bad leadership over history can be traced to psychopathic personalities incl. Hitler, Stalin, and Napoleon (e.g. Neumayr 1995).

It is important to note that while psychopaths do not feel another person’s suffering, they can notice it, while autists cannot notice but generate feelings and possible sense suffering subconsciously (Lehrer 2009). While many researchers assume that psychopathy is a spectrum disorder as well (Patrick 2006), some argue it is a discrete genetic defect (Lawrence 2007, 2010). While the verdict is out on either of these positions, the general boundary psychopathy poses to compassion activation is real.

The second dispositional limit to emotional processing is based on a problem with the prefrontal cortex or the frontal lobe. The most famous case of such a boundary condition is presented by Phineas Gage who survived the impact of an iron rod through his head. As recounted by Damasio (2005), Gage became asocial and lacked compassion, as he was incapable to process emotions after the accident, a condition that has been observed by other patients with similar lesions. While this conditions is rather rare it presents a further dispositional limit to compassion activation, which so far has not been remedied.

-

Proposition 2a: Individual dispositional boundaries to compassion activation stem from emotional insufficiencies such as psychopathy of frontal lobe lesions.

Situational Emotional Boundaries to Compassion Activation

Hoffman (1981) suggests that there may be a range of optimal empathic arousal, within which individuals are able to respond. He also suggests, that there are areas of empathic over-arousal which lead to avoidance behavior. Such behavior has been found in nurses dealing with terminally ill patients (Stotland 1978). Maslach (1982) describes the various situational limits in which people capable to feel other people’s suffering stop and turn off such empathic reaction, because of emotional overload. One such manifestation is emotional exhaustion or burnout. This phenomenon has been studied particularly in the helping professions, such as nurses, palliative care takers, or AIDS volunteers. Kinnick et al. (1996) state that in the workplace such emotional overload manifests itself by the feeling that one is no longer able to give oneself to others, and through an armor of detachment and depersonalization, which Maslach (1982) characterizes as a cold indifference to others’ needs and a callous disregard for their feelings.

While emotional overload has been studied as a boundary to compassion activation specifically in the interpersonal realm, evidence is accruing that emotional overload can be generated by mass communication patterns as well. Moeller (1999) finds that the mass media communication of suffering induces compassion fatigue. Issue life cycle theorists further argue that because of empathy saturation, messages depicting other people’s suffering will not generate any emotional response and even generate avoidance behavior after a certain number of repetitions (Downs 1972; Hilgartner and Bosk 1988). It is hence argued that those with the general capacity to feel other people’s suffering can experience situations which limit compassion activation because of emotional overload.

-

Proposition 2b: Individual situational boundaries to compassion activation stem from emotional overload.

Boundaries to Compassion Mobilization

Based on the above account, we now to turn to the behavioral dimension of compassion capability, which refers to the capacity to respond to another’s person suffering.

Dispositional Behavioral Boundaries to Compassion Mobilization

It seems intuitive that the ability to respond to another person’s suffering requires mental and physical dispositions, such as the ability to speak and respond, hug a person, or help to carry a person in need, etc. While there are a number of mental and physical disabilities preventing people from responding to other people’s suffering (Parry and American Bar Association. Commission on Mental and Physical Disability Law 1994), there are further boundaries for compassion mobilization induced by character and personality development (Kegan 1982).

Moral philosophers view character as a) a distinctive combination of personal qualities by which someone is known (that is personality) and b) moral strength or integrity (Wilson 1993). Wilson (1993) further argues those people with the most admirable character are those who are the best balanced, which in common parlance are referred to as ‘nice persons’ or ‘good guys’. A nice person, Wilson argues, takes into account the feelings of others when deciding about his/her actions and does not inflict unjustified harm on innocent parties. As Wilson (1993) defines it, a good character is not demonstrated by a life lived according to a rule, since there rarely is a rule by which good qualities ought to be combined or hard choices resolved; rather it is demonstrated by a life lived in balance. Lawrence (2010) comes to the same conclusion about good leadership. Developmental psychologists argue that that kind of character develops over time (Kegan 1982; Kohlberg 1984) and that it predicts a certain kind of relationship quality people develop. Kegan (1982) and Gilligan (1993) make the point that people on a certain development level are more likely to behave compassionately because they have learned to be other oriented. Similarly in any situation in which suffering is non-routine it seems that persons in the fourth order of consciousness (Kegan 1982) are able to respond more flexibly and mindfully to other people’s suffering.

-

Proposition 3a: Character and personality development can limit compassion mobilization.

Situational Behavioral Boundaries to Compassion Mobilization

There is accumulated evidence that behavioral responses to other people’s suffering are determined by the situation (see e.g. Alzola 2008; Davis-Blake and Pfeffer 1986). Drawing on the account presented by Dutton et al. (2006), compassion mobilization depends on resources (cards, donations, course material), and therefore any situational limit to an individual’s resources present a boundary to compassion capability. Furthermore, compassion mobilizing as the actual action to relieve pain also requires a certain skill set. In the aftermath of earthquakes, for example skilled search teams, aid workers, and trauma psychologists are required. While minor suffering can be alleviated by potentially unskilled people, a lot of suffering alleviation requires not only resources but specific knowledge. Any shortage of such knowledge will present a boundary condition for the capability to respond to suffering and limit the potential for compassion organizing. Finally, as Batson (1990) argues there are competing concerns that impede compassion mobilization because of other more pressing demands (including lack of will or fear). As several experiments show such competing concerns don’t have to be egoistical in nature but can also be induced by authority structures (Milgram 1974; Zimbardo 1974)s, time pressures (Darley and Batson 1973), and group effects (Latane and Rodin 1969).

-

Proposition 3b: Insufficient Resources, inadequate skills, and competing concerns can limit compassion mobilization.

Perspective on Individual Level Boundaries to Compassion Organizing

The various scientific narratives on compassion capability deliver interesting insights regarding the boundaries to compassion organizing. These boundaries are structurally different, and thus they provide a number of perspectives as to potential remedies (e.g. screening or training).

The accounts of autism and psychopathy support the narrative of compassion as a fiction. In fact it is argued that homo oeconomicus is a psychopath and therefore economic man is indeed not able to be compassionate. While it seems that this account is marginally relevant Lawrence (2010) as well as Babiak and Hare (2006) argue that psychopaths have much more influence in real life via emotional contagion effects that are enhanced by social structures (see Babiak and Hare 2006; Bakan 2004; Blair et al. 2005; Lawrence 2010; Sutton 2010 for a similar argument).

The fact that autists and psychopaths are exceptions to the rule, however, supports the narrative for compassion as a quasi default. Almost universal human capacity to notice (cognitively) and feel (emotionally) is supported by accounts of evolutionary psychologists, neuropsychologists and anthropologists (Darwin 1909a; Diamond 1992; Lehrer 2009; Wilson 1993). The behavioral compassion mobilization component allows for the argument of both positive deviance and a quasi-universal potential.

Clearly, while not a universal default compassion activation can happen and will happen for most people as a norm (unless cognitively or emotionally overloaded). How they respond to the activation is a question of motive, which brings in the possibility of compassion organizing as a positively deviant behavior as well as an aspirational goal.

Developing a Typology of Compassion Capability

As mindsets and habits develop based on situations and dispositions (Dweck 2008), we argue that certain types of compassion capability can be observed. Based on the above outlined dispositional and situational boundaries of compassion activation and compassion mobilization (Table 1), we develop archetypes to propose a typology of individual-level compassion capability. As Dutton et al. (2006) state human agency and social architecture transform individual compassion into a social reality, we argue that the locus of compassion organizing resides in individual level compassion capability that organizational structures can support or counteract in a typological manner. Following that logic, we will base the typology on the boundaries of individual level compassion capability and then extend it to resulting organizing modes, providing insights into the boundaries of compassion organizing.

Individual Modes of Compassion Capability

Authentic Indifference

The first individual compassion capability mode (see Fig. 1) we label authentic indifference. This mode represents the absence of compassion activation and the absence of compassion mobilization. This type of compassion capability can be caused by cognitive and emotional boundaries to compassion activation, such as autism and related disorders, psychopathy and related disorders, as well as cognitive and emotional overload. In contrast to the mode of socialized psychopathy, authentic indifference is manifested by the absence of any level of compassion mobilization.

People high on the autism spectrum and psychopaths are not able to compassion activate. Taken together these cases would represent between 1.5%- 2.75% of the population (based on U.S. estimates; http://www.cdc.gov/) for whom there is no remedy at this point (Baron-Cohen 1995; Patrick 2006). In contrast to socialized psychopathy (next section) the authentic indifference category includes psychopaths lacking in intelligence that often act in very self destructive manners. These individuals do not possess the cognitive intelligence to learn social conventions and often end up as drug addicts or in prison (Blair et al. 2005; Lehrer 2009). In fact, it is estimated that about 25% of the overall prison population is psychopathic and 50% of those with murder charge (Lawrence 2007; Lehrer 2009), which highlights the significance of the authentic indifference mode of compassion capability.

While these examples represent the dispositional cause of authentic indifference, there are those individuals that express authentic indifference despite a potential for compassion activation. Those individuals are either cognitively or emotionally overloaded (or both) and therefore similarly unable to either activate or mobilize their compassion capability. Such compassion fatigue (Figley 2002; Moeller 1999) is arguably increasing in salience. Scholars argue that given the conditions of modern life, marked by instant information access, permanent connectivity, as well as the increased emotional stimulation a growing number of people to numb down, and turn indifferent to the suffering occurring around them (Mosley 2000). An extreme case of authentic indifference is presented by those in the helping professions that suffer from burnout. In the state of burnout, they have actually transformed from authentic compassion to authentic indifference because of emotional overload (Halbesleben and Buckley 2004). It is estimated that overall 37% of the American Workforce is affected by burnout symptoms (Solman 2010). Whereas these statistics may vary, they further highlight the relevance of the authentic indifference mode.

In contrast to the dispositional boundaries, there might be interventions that can restore compassion activation and compassion mobilization in those people suffering from cognitive and emotional overload. Such interventions could take the form of simple vacations, focused retreats, meditation, or guided therapies (e.g. Gibelman and Furman 2008) .

Socialized Psychopathy

While it seems counterintuitive to develop a mode for those that are unable to activate but mobilize compassion, because the latter presupposes the former, the case of socialized psychopaths presents an interesting and relevant anomaly (Babiak and Hare 2006; Blair et al. 2005; Hare 1999). Socialized psychopaths in contrast to authentic psychopaths are able to hide their psychopathy. As Hare (1999) argues they make up for their lack of emotional capabilities with cognitive capabilities. They are able to learn compassion expressions despite their inability to authentically feel them. They understand that to function well in society, they need to play along. Babiak and Hare (2006) suggest that socialized psychopaths are able to fake compassion very well, precisely because they lack any deep feeling.

Socialized psychopaths try to conform to social standards and expectations. While they cannot care and are only interested in fulfilling their drive to acquire and drive to defend (Lawrence and Nohria 2002a), they understand that these drives can be served better, when psychopathy is masked (Lawrence 2010). As such they outwardly try to conform to social expectations, pay lip service to many agreements, and often raise public attention to their socially desired actions. While they enter such agreements, they do so to better serve their ultimate motive. As a consequence they can easily break them as they do not feel any sense of obligation or moral pain. Some of the most prominent recent examples of such socialized psychopaths are Bernard Madoff and Jeffrey Skilling. These individuals are very smart cognitively and are able to learn whatever is necessary to succeed, including common expressions of sympathy, empathy and compassion. That way they are able to gain trust of very influential and intelligent people, who they abuse in their quest for power and material success (Blair et al. 2005; Lawrence 2010). As is suggested by Babiak and Hare (2006) socialized psychopaths can function very well in environments that reward their emotional insufficiency, such as in the corporate business world. Despite their absolute number (below 1% of the total population) Babiak and Hare (2006) argue that they are disproportionally attracted to environments that allow them to satisfy their drive for power, wealth and status. It is estimated that about 6% of the corporate workforce display traits of socialized psychopathy (Babiak and Hare 2006; Lawrence 2010). Sutton (2007) based on a similar argument, suggest that the number of such people which he labels assholes, can reach up to 10%. These people respond to suffering only when socially required, and when such compassion mobilization is considered advantageous to their career success.

According to Patrick (2006), clinicians generally believe that there is no cure for such socialized psychopaths. As a consequence many authors suggest to screen such people out entirely, so as to not create a culture of psychopathic contagion (see e.g. Sutton 2007).

Compassion Constipation

In analogy to the notion of moral constipation (West and Smiley 2008), the mode of compassion constipation describes the condition in which people experience compassion activation, but lack compassion mobilization. The reasons for such lack of response to another person’s suffering could reside either in a dispositional inability or in situational limitations. Despite sound compassion activation, a lack of compassion mobilization could be triggered by mental or physical handicaps as well as limited character or personality development. This mode of compassion constipation can be witnessed e.g. when a child is unable to console her mother despite intact compassion activation. Further, such compassion constipation can be witnessed when people do not feel capable to respond to others’ suffering because of insufficient resources, inadequate abilities (perceived or real) and competing concerns.

Scholars such as Goleman (1995) in his work on emotional intelligence suggest that compassion and bonding need to be learned and refined, despite an innate capability (see also Gilligan 1993; Kegan 1982; Kohlberg 1984). With the exception of psychopaths this assumption applies to the majority of people not affected by cognitive or emotional overload. However, there is the potential for a reverse learning process that can also lead to compassion constipation. Cultural contexts, for example, can lead people to suppress their compassion mobilization. Hofstede (1980, 2001) argues that there are organizational cultures high in masculinity, which place a strong emphasis on competitiveness, assertiveness, ambition, and the accumulation of wealth and material possessions. Lawrence (2007) e.g. suggests that these cultural contexts create a type of psychopathic contagion effect. This means that members of the organization, despite an ability to notice and feel other people’s suffering, suppress the mobilization of compassion for fear of not fitting in (see e.g. Ely and Meyerson 2008). Similarly, what Deal and Kennedy (1982, 1999) term the Tough-Guy Macho Culture can lead to such compassion constipation since compassion is considered a signal for weakness.

Overall many of the people classified within the compassion constipation mode, could be activated to become authentically compassionate by ways of training. Training aimed at character development, personal maturity, or dealing with perceived and real inadequacies as well as competing preferences. Such training would however require serious and concerted efforts.

Authentic Compassion

The mode of authentic compassion describes the condition in which people experience compassion activation and mobilize compassion responses for those people whose suffering they notice. In contrast to the people in compassion constipation mode, authentic compassionates are not only noticing and feeling the suffering of others, but they actually respond to the suffering in whatever way they can (see e.g. accounts presented by Drayton 2006; Yunus 2008). Many of those populating the mode of authentic compassion are not only able to respond to other people’s suffering, but rather develop a habit to employ their compassion capability (Elkington and Hartigan 2008). Similar to what Aristotle calls virtue development, they actively seek ways on how to respond to suffering of those around them (Bornstein 2007). Prototypes of people in the Authentic Compassion mode are often met within the helping professions (Richie-Melvan and Vines 2010). Furthermore such people can be seen in organizations that focus on relieving pain, such as churches, NGO’s, or social enterprises (Bornstein and Hart House 2005; Elkington and Hartigan 2008; Yunus 2008).

Organizing Modes of Compassion Capability

Individual modes of compassion capability are expressed and developed in relational contexts. Such relational contexts are predominant in organizational entities. These organizational entities vary according to their structures, goals, and routines, which reflect and influence individual behavior and the ability to compassion organize. In adopting a focus on organizing, structures and actions with regard to compassion capability take center stage (Dutton et al. 2006). We develop our typology (see Fig. 2) based on the interplay of actions which are taken by individuals that possess human agency and structures reflected by organizational objectives, values, incentive structures, routines, culture, and surrounding networks.

Based on the individual modes of compassion capability we will now outline the corresponding modes of organizational capability to compassion organize. The ensuing framework suggests in which organizational contexts compassion organizing is possible, impossible, fake, or suppressed. While we acknowledge that in reality organizing styles will not fall in either category directly, we argue that there is a tendency based on the structures and people an organizational environment hosts to largely correspond with one of the archetypal modes.

Psychopathic Organizing

In organizational contexts in which people display authentic indifference, actions will neither activate nor mobilize compassion. We label this mode psychopathic organizing. Psychopathic organizing is the result of either severe cognitive or emotional overload (e.g. burnout) or significant influence of autistic or psychopathic individuals in the organizing process. Such individual level authentic indifference can be supported through organizational structures that allow emotional and cognitive overload, as well as encourage autistic or psychopathic behavior.

Values that support such psychopathic organizing are oriented towards domination, power, and wealth (Deal and Kennedy 1982; Dutton et al. 2006; Hofstede 2001; Lawrence 2010). Furthermore such values are not concerned with the well being of humanity at large, but only a particular group such as shareholders or gang members. The values are also strongly geared towards the individual and are not concerned with relational dimension of human existence (Brickson 2007). In addition, structures that value and enforce short term relations, which are transactional in nature support psychopathic organizing (Brickson 2005; Dierksmeier and Pirson 2009).

Routines that support such psychopathic organizing reinforce the above mentioned values, are geared to the individual and reward efforts towards single minded wealth creation, power attainment, and domination (e.g. Deal and Kennedy 1999). Such routines exclude concern for other people’s suffering, in that they become very transactional, focused, specialized, and formalized (Weber and Andreski 1983). Rule orientation and rigidity can further support the process of psychopathic organizing as described in critiques of hierarchical organizing (Leavitt 2005), the assembly line (Mayo 1933) or the corporation as organizing mechanism in general (Bakan 2004).

Networks that support such psychopathic organizing are composed of organizations with similar values and routines. As suggested by Lawrence (2010) and Bakan (2004) market based networks support psychopathic organizing. As price is the only coordinating mechanism, indifference to other human concerns such as suffering is supported.

As Babiak and Hare (2006) state psychopaths are indeed attracted by the structures described above, since their genetic dysfunction becomes socially rewarded. Organizational forms that are transaction as well as command and control oriented are fertile grounds for psychopathic organizing. Many scholars suggest that in these contexts care and concern for others is actually limiting performance (Bakan 2004; Lawrence 2010; McLean and Elkind 2004). Areas in which psychopathic organizing is prevalent are organized crime (Gambetta 2009), investment banking (Lawrence 2010), general trading, and other transactional oriented businesses (such as used car dealing) as well as within strong hierarchies such as the military (Munson 1916; Patrick 2006).

Acquiescent Organizing

In organizational contexts in which people display socialized psychopathy, actions will not activate but possibly mobilize compassion. We label this mode acquiescent organizing. Acquiescent organizing is the result of significant influence by socialized psychopathic individuals in the organizing process. Individual level socialized psychopathy can be supported through organizational structures that encourage psychopathic behavior, but demand external restraints in line with societal expectations of behavioral conduct.

Values that support such acquiescent organizing are very similar to the ones embraced in the mode of psychopathic organizing. However, while these values correspond to the enacted values, the espoused values (Argyris and Schön 1978; Simons 2002) are in line with societal expectation of good citizenship. Furthermore such socially acceptable values are actively communicated to the outside stakeholders in order to mask enacted values and assuage societal concerns.

Routines that support such acquiescent organizing serve the psychopathic enacted values, and the espoused values that appease concerns with such enacted values. While a first set of routines will be identical to the ones in the psychopathic organizing mode, the second set of routines is concerned with the outside image created. The second set of routines contains a focus on external and possibly internal communication to present the first set of routines as compliant with the espoused values. To make sure that the message to outside audience is controlled, public relation routines become crucial (e.g. Cutlip 1995).

Networks that support such acquiescent organizing are composed of organizations that support the espoused values as well as organizations that share the same enacted values. As suggested by Vogel (2005) acquiescent organizing often occurs because the network includes institutions concerned with societal implications, such as regulators, NGO’s, or local governments. In addition, as suggested by Lawrence (2007), and Bakan (2004) the same market based networks that support psychopathic organizing, support the actions and routines of acquiescent organizing modes. Again, as price is the only coordinating mechanism, indifference to other human concerns is supported.

In organizational contexts acquiescent organizing could be exemplified by organizations that are by law required to profit maximize, while social expectations require these organizations to also pay attention to the social good. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is often viewed as the result of such acquiescent organizing where psychopathic organizations are required to do what is unnatural to them (Friedman 1970). As a result the CSR activities often seem little less than exercises of public acquiescence and are criticized as white or green-washing (Laufer 2003; MacDonald 2008; Munshi and Kurian 2005). Enron presents a prime example of an organization which embraced acquiescent organizing; it was widely admired for its corporate governance and corporate social responsibility activities, while psychopathically pursuing profit without concern for other people’s suffering (McLean and Elkind 2004).

Mechanic Organizing

In organizational contexts in which people display compassion constipation, actions will activate but not mobilize compassion. We label this mode mechanic organizing. Mechanic organizing is the result of significant influence by compassion constipated individuals in the organizing process. Individual level compassion constipation, however, is structurally supported by values, routines, and networks that encourage suppression of compassion mobilization.

Terminal values (Rokeach 1979) that support such mechanic organizing can be manifold. They can support compassion activation or downplay it (e.g. be in the service of a suffering part of society or not). Instrumental values (Rokeach 1979), however, do support the suppression of situation specific compassion mobilization. Such values embrace rationalization and impersonality. They further support the hierarchy of authority, command and control, written rules of conduct, and favor specialized division of labor to achieve overall efficiency (Gawthrop 1997; Weber and Andreski 1983; Weber et al. 2009).

Routines that support such mechanic organizing reinforce the above mentioned instrumental values, are geared to rationalization and impersonality and exclude concern and care for individual suffering. Such bureaucratic routines focus on the application of rules first and foremost and are concerned with general outcomes rather than responses to individual suffering. The bureaucratic routines require specialized division of labor which supports a limited perspective of an individual as a depersonalized case to be managed rather than a human being with human needs to be addressed.

Networks that support such mechanic organizing are rather homogenous and mostly composed of similar mechanically organizing bureaucratic institutions. The collaboration between such network members follows similar bureaucratic approaches and is rule rather than trust based. Compassion mobilization as a consequence is further suppressed by the resulting network effects.

Compassion Organizing

Compassion organizing as described by Dutton et al. is possible only within a context where human agency is driven by compassion and support structures are supportive of compassion activation and compassion mobilization. For a further discussion of the values, routines, and networks supportive of compassion organizing we defer to Dutton et al. (2006).

Concluding Remarks

Given the amount of global and local crises, the concept of compassion organizing presents a much needed managerial perspective on how to deal with the ensuing suffering. Furthermore, compassion organizing presents a stepping stone for a renewed, human centered paradigm for management research. Because of this vast theoretical and practical relevance it is important to understand the boundary conditions for such a theory and practice to develop.

It is the point of this paper to explore the generality of compassion organizing as a concept and test the boundaries of its underlying assumptions. While the paper uses the individual as an entry point to the boundary discussion we extend these insights onto the level of organizing modes via the creation of compassion capability archetypes. This allows us to examine alternative modes of compassion organizing that also enable us to understand the potential and the limit of compassion organizing.

Change processes towards authentic compassion organizing are rare and difficult. To manage change towards compassion organizing it is crucial to understand which form of organizing is predominant at the organization in question. In organizations in which psychopathic organizing is the main orientation it is impossible to get to authentic compassion, because the compassion ability is missing. All that is possible is changing towards acquiescent organizing. Organizations that are predominantly mechanistically organized can possibly be turned into authentic compassion organizers, if the reasons for compassion constipation are identified and removed. One account that could highlight such a transition is presented by Ely and Meyerson (2008). They describe how a strongly male-oriented culture was transformed into an authentically caring culture by focusing on a change in values and routines.

Many of the boundary conditions that undermine compassion organizing unfortunately deal with major features of our current economic structure. The dominance of market structures for example induces a psychopathic mode of organizing, and only when certain routines and values keep the market functions in check can the relational aspects of human organizing prevail. The prevalence of bureaucratic structures supporting Western-type democracies further undermine compassion organizing in that they create what Weber termed “the polar night of icy darkness” (Weber et al. 1994). In many organizations that aim at relieving suffering such as churches or NGO’s, similar mechanistic structures seem to develop and allow to undermine compassion organizing effectiveness (e.g. Ebrahim 2003).

Out of this impasse, however, new forms of organizations are developing. These organizations are trying to combine the effectiveness of market oriented organizations with the purpose of compassion oriented organizations. Such organizations are interchangeably called social enterprises (Rangan 2007), for-benefit organizations (Sabeti 2008), humanistic businesses (Kimakowitz et al. 2010) or sustainable corporations (Senge 2010).

While these efforts are relatively recent it is argued that new support structures for compassion organizing need to be developed. Some say new organizational forms are required (Sabeti 2008), others say a new support structures (Yunus 2008), including social stock exchanges, social rating agencies, compassion oriented media. Finally, it is argued that changes in the educational support system (Bloom 2006) are equally important to give rise to such a new generation of compassion organizing individuals and institutions.

References

Alzola, M. 2008. Character and environment: The status of virtues in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics 78 (3): 343–357.

Argyris, C., and D.A. Schön. 1978. Organizational learning. Reading: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co..

Babiak, P., and R.D. Hare. 2006. Snakes in suits : when psychopaths go to work. 1st ed. New York: Regan Books.

Bakan, J. 2004. The Corporation : The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power: Penguin Books, Canada.

Baron-Cohen, S. 1995. Mindblindness : an essay on autism and theory of mind. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Baron-Cohen, S., S. Wheelwright, J. Hill, Y. Raste, and I. Plumb. 2001. The 'Reading the Mind in the eyes' test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger Syndrome or High-Functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 42: 241–252.

Batson, C.D. 1990. How social an animal? American Psychologist 45 (3): 336–346.

Blair, J., D.R. Mitchell, and K. Blair. 2005. The psychopath : emotion and the brain. Malden: Blackwell Pub.

Bloom, G. 2006. The Social Entrepreneuship Collaboratory (SE Lab): A university Incubator for a rising generation of Social Entrepreneurs. In Social Entrepreneurship -new models for sustainable social change, ed. A. Nicholls. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bornstein, D. 2007. How to change the world (Updated ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bornstein, D., and Hart House. 2005. So you want to change the world? : the emergence of social entrepreneurship and the rise of the citizen sector. Toronto: Hart House, University of Toronto.

Brickson, S.L. 2005. Organizational identity orientation: Forging a link between organizational identity and organization's relations with stakeholders. Administrative Science Quarterly 50: 576–609.

Brickson, S.L. 2007. Organizational Identity Orientation: The Genesis of the Role of the Firm and Distinct Forms of Social Value. Academy of Management Review 32 (3): 864–888.

Brockner, J., and E.T. Higgins. 2001. Regulatory Focus Theory: Implications for the Study of Emotions at Work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 86 (1): 35–66.

Cleckley, H.M. 1982. The mask of sanity. Rev. ed. New York: New American Library, Mosby.

Cooper, R.K., and A. Sawaf. 1996. Executive EQ: Emotional intelligence in leadership and organizations. New York: Grosset/Putnam.

Cutlip, S.M. 1995. Public relations history : from the 17th to the 20th century : the antecedents. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Damasio, A.R. 2005. Descartes' error : emotion, reason, and the human brain. London: Penguin.

Darley, J.M., and C.D. Batson. 1973. From Jerusalem to Jericho: A Study of Situational and Dispositional Variables In Helping Behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 27: 100–108.

Darwin, C. 1909a. The descent of man and selection in relation to sex. 2d. ed. New York: D. Appleton and company.

Darwin, C. 1909b. The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. New York: Appleton and Company.

Davis-Blake, A., and J. Pfeffer. 1986. Just a Mirage: The Search for Dispositional Effects in Organizational Research. Academy of Management Review 14: 385–400.

Deal, T.E., and A.A. Kennedy. 1982. Corporate cultures : the rites and rituals of corporate life. Reading: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co..

Deal, T.E., and A.A. Kennedy. 1999. The new corporate cultures : revitalizing the workplace after downsizing, mergers, and reengineering. Reading: Perseus Books.

Diamond, J.M. 1992. The third chimpanzee : the evolution and future of the human animal. 1st ed. New York: HarperCollins.

Dierksmeier, C., and M. Pirson. 2009. Oikonomia Versus Chrematistike: Learning from Aristotle About the Future Orientation of Business Management. Journal of Business Ethics 88 (3): 417–430.

Downs, A. 1972. Up and Down with Ecology- The Issue-Attention Cycle. The Public Interest 28: 28–50.

Drayton, W. 2006. The citizen sector transformed. In Social Entrepreneurship- new models for sustainable social change, ed. A. Nicholls. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dutton, J.E., M.C. Worline, P.J. Frost, and J. Lilius. 2006. Explaining compassion organizing. Administrative Science Quarterly 51 (1): 59–96.

Dweck, C.S. 2008. Mindset : the new psychology of success (Ballantine Books trade pbk. ed.). New York: Ballantine Books.

Ebrahim, A. 2003. NGOs and organizational change : discourse, reporting, and learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Elkington, J., and P. Hartigan. 2008. The power of unreasonable people : how social entrepreneurs create markets that change the world. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Ely, R.J., and D. Meyerson. 2008. Unmasking Manly Men. Harvard Business Review 86 (7/8): 20.

Figley, C.R. 2002. Treating compassion fatigue. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Friedman, M. 1970. The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York Times Magazine, September 13: 1970.

Gambetta, D. 2009. Codes of the underworld : how criminals communicate. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gawthrop, L.C. 1997. Democracy, Bureaucracy, and Hypocrisy Redux: A Search for Sympathy and Compassion. Public Administration Review 57 (3): 205–210.

Gibelman, M., and R. Furman. 2008. Navigating human service organizations. 2nd ed. Chicago: Lyceum Books.

Gilbert, P. 2005. Compassion : conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy. London: Routledge.

Gilligan, C. 1993. In a different voice : psychological theory and women's development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Goleman, D. 1995. Emotional Intelligence. New York: Bantam Books.

Halbesleben, J.R.B., and M.R. Buckley. 2004. Burnout in organizational life. Journal of Management 30: 859–879.

Hare, R.D. 1999. Without conscience : the disturbing world of the psychopaths among us. New York: Guilford Press.

Hart, S. 2005. Capitalism at the Crossroads : The Unlimited Business Opportunities in Solving the World's Most Difficult Problems. New Jersey: Wharton School Publishing.

Health, N. C. f. N. 2010. NINDS Autism Information Page.

Henrich, J., Boyd, R., Bowles, S., Camerer, C., Fehr, E., Gintis, H., & McElreath, R. 2001. In Search of Homo Economicus: Behavioral Experiments in 15 Small-Scale Societies. American Economic Review, 91(2): 73–78.

Hilgartner, S., and C.L. Bosk. 1988. The Rise and Fall of Social Problems. American Journal of Sociology 94: 53–78.

Hoffman, M. 1981. Is Altruism Part of Human Nature. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 40: 121–137.

Hofstede, G.H. 1980. Culture's consequences : international differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Hofstede, G.H. 2001. Culture's consequences : comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Jackson, I., and J. Nelson. 2004. Profits with Principles- seven strategies for delivering value with values. New York: Currency Doubleday.

Kahneman, D., P. Slovic, and A. Tversky. 1982. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kanner, L. 1968. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Acta Paedopsychiatrica 35 (4): 100–136.

Kegan, R. 1982. The evolving self : problem and process in human development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kimakowitz, E., Pirson, M., Spitzeck, H., & Dierksmeier, C. 2010. Humanistic Management in Action. In T. H. M. Network (Ed.), Humanistic Management in Action- London: Palgrave McMillan.

Kinnick, K.N., D.M. Krugman, and G.T. Cameron. 1996. Compassion Fatigue: Communication and Burnout Toward Social Problems. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 73 (3): 687–707.

Kirsh, D. 2000. A Few Thoughts on Cognitive Overload. Intellectica 1 (30): 19–51.

Kohlberg, L. 1984. The Psychology of Moral Development: The Nature and Validity of Moral Stages. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

Latane, B., and J. Rodin. 1969. A Lady in Distress: Inhibiting Effects of Friends and Strangers on Bystander Intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 37: 822–832.

Laufer, W.S. 2003. Social accountability and corporate greenwashing. Journal of Business Ethics 43 (3): 253–261.

Lawrence, P. 2007. Being human - a renewed darwinian theory of human behavior. www.prlawrence.com. Cambridge, MA.

Lawrence, P. 2010. Driven to Lead: Good, Bad, and Misguided Leadership: Jossey- Bass. San Francisco.

Lawrence, P., and N. Nohria. 2002a. Driven: How Human Nature Shapes Our Choices. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Lawrence, P.R., and N. Nohria. 2002b. Driven : how human nature shapes our choices. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Leavitt, H.J. 2005. Top down : why hierarchies are here to stay and how to manage them more effectively. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

LeDoux, J.E. 1996. The emotional brain : the mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Lehrer, J. 2009. How we decide. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

MacDonald, C.C. 2008. Green, inc. : an environmental insider reveals how a good cause has gone bad. Guilford: Lyons Press.

Margolis, J.D., and J.P. Walsh. 2003. Misery loves companies: Rethinking social initiatives by business. Administrative Science Quarterly 48 (2): 268–305.

Maslach, C. 1982. Burnout, the cost of caring. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Mayer, J.D., R.D. Roberts, and S.G. Barsade. 2008. Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annual Review of Psychology 59: 507–536.

Mayo, E. 1933. The human problems of an industrial civilization. New York: Macmillan.

McLean, B., and P. Elkind. 2004. The smartest guys in the room : the amazing rise and scandalous fall of Enron. New York: Portfolio.

Milgram, S. 1974. Obedience to Authority. New York: Harper and Row.

Moeller, S.D. 1999. Compassion fatigue : how the media sell disease, famine, war, and death. New York: Routledge.

Mosley, I. 2000. Dumbing down : culture, politics, and the mass media. Thorverton: Imprint Academic.

Munshi, D., and P. Kurian. 2005. Imperializing spin cycles: A postcolonial look at public relations, greenwashing, and the separation of publics. Public Relations Review 31 (4): 513–520.

Munson, E. 1916. The military surgeon. Journal of the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States: 38.

Neumann, C.S., and R.D. Hare. 2008. Psychopathic traits in a large community sample: links to violence, alcohol use, and intelligence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 76 (5): 893–899.

Neumayr, A. 1995. Dictators in the mirror of medicine : Napoleon, Hitler, Stalin. Bloomington: Medi-Ed Press.

Nisbet, R.A. 2003. The present age : progress and anarchy in modern America. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Parry, J., and American Bar Association. Commission on Mental and Physical Disability Law. 1994. Mental disabilities and the Americans with Disabilities Act : a practitioner's guide to employment, insurance, treatment, public access, and housing. Washington, DC: American Bar Association's Commission on Mental and Physical Disability Law.

Patrick, C.J. 2006. Handbook of psychopathy. New York: Guilford Press.

Prahalad, C.K. 2005. The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid: eradicating poverty through profits. Wharton School Publishing.

Rangan, V.K. 2007. Business solutions for the global poor : creating social and economic value. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Rice, C. 2009. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders. Center for Disease Control.

Richie-Melvan, S.I., and D. Vines. 2010. Angel walk : nurses at war in Iraq and Afghanistan. Portland: Arnica Pub.

Rizzolatti, G. 1998. What happened to Homo habilis? (Language and mirror neurons). Behavioral and Brain Sciences 21 (4): 527–528.

Rizzolatti, G., L. Fogassi, and V. Gallese. 2000. Mirror neurons: Intentionality detectors? International Journal of Psychology 35 (3–4): 205–205.

Rizzolatti, G., L. Fogassi, and V. Gallese. 2001. Neurophysiological mechanisms underlying the understanding and imitation of action. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2 (9): 661–670.

Rokeach, M. 1979. Understanding human values : individual and societal. New York: Free Press.

Sabeti, H. 2008. The For Benefit Corporation - creating a new organizational archetype. In T. F. S. Network (Ed.). Washington. D.C.: Aspen Institute.

Senge, P.M. 2008. The necessary revolution : how individuals and organizations are working together to create a sustainable world. 1st ed. New York: Doubleday.

Senge, P.M. 2010. The necessary revolution : working together to create a sustainable world (1st pbk. ed.). New York: Broadway Books.

Simons, T. 2002. Behavioral integrity: The perceived alignment between managers' words and deeds as a research focus. Organization Science 13 (1): 18–35.

Smith, A. 1759. The theory of moral sentiments. London: A. Millar.

Smith, G.N. 2002. Radical compassion : finding Christ in the heart of the poor. Chicago: Loyola Press.

Solman, P. 2010. Stress, Burnout Taking Toll on Many Still in U.S. Workforce. In NewsHour, ed. J. Lehrer. New York: PBS.

Spreitzer, G.M., and S. Sonenshein. 2004. Toward the construct definition of positive deviance. American Behavioral Scientist 47 (6): 828–847.

Stotland, E. 1978. Empathy, fantasy, and helping. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Sutton, R.I. 2007. The no asshole rule : building a civilized workplace and surviving one that isn't. 1st ed. New York: Warner Business Books.

Sutton, R.I. 2010. The no asshole rule : building a civilized workplace and surviving one that isn't (1st trade ed.). New York: Business Plus.

Sutton, R.I., and B.M. Staw. 1995. What Theory is Not. Administrative Science Quarterly 40 (3): 337–384.

Thupten, J. 2005. Essence of the Heart Sutra : the Dalai Lama's heart of wisdom teachings (1st pbk. ed.). Boston: Wisdom Publications.

Titmuss, C. 2001. The Buddha's book of daily meditations : a year of wisdom, compassion, and happiness. 1st ed. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Vogel, D. 2005. The market for virtue : the potential and limits of corporate social responsibility. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Waddington, P. 1996. Dying for information: an investigation of information overload in the UK and world-wide. London: Reuters Business Information.

Weber, M., and S. Andreski. 1983. Max Weber on capitalism, bureaucracy, and religion : a selection of texts. London: Allen & Unwin.

Weber, M., P. Lassman, and R. Speirs. 1994. Weber : political writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Weber, S., U. Habel, K. Amunts, and F. Schneider. 2008. Structural brain abnormalities in psychopaths-a review. Behavioral Sciences & the Law 26: 7.

Weber, M., H.H. Gerth, and C.W. Mills. 2009. From Max Weber : essays in sociology. Abingdon: Routledge.

Weick, K.E. 1979. The social psychology of organizing (2d ed.). Reading: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co..

Weick, K. 1995. What theory is not, theorizing is. Administrative Science Quarterly 40 (3): 385–390.

West, C., & Smiley, T. 2008. Hope on a tightrope : words & wisdom (1st ed.). Carlsbad: Smiley Books : Distributed by Hay House.

Williamson, O.E. 1979. Transaction Cost Economics: The Governance of Contractual Relations. Journal of Law and Economics, October 22: 233–261.

Wilson, J.Q. 1993. The moral sense. New York: Free Press, Maxwell Macmillan Canada, Maxwell Macmillan International.

Wurman, R.S. 1990. Information Anxiety : What to Do When Information Doesn't Tell You What You Need to Know. New York: Bantam.

Wuthnow, R. 1991. Acts of compassion : caring for others and helping ourselves. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Yunus, M. 2008. Social Entrepreneurs are the Solution. In Humanism in Business: Perspectives on the Development of a Responsible Business Society, ed. H. Spitzeck, M. Pirson, W. Amann, S. Khan, and E. von Kimakowitz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zimbardo, P. 1974. On Obedience to Authority. American Psychologist 29 (7): 566–567.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pirson, M. Exploring the Boundaries of Compassion Organizing. Humanist Manag J 2, 151–169 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41463-017-0028-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41463-017-0028-4