Abstract

This conceptual review seeks to reframe the view of academic integrity as something to be enforced to an academic skill that needs to be developed. The authors highlight how practices within academia create an environment where feelings of inadequacy thrive, leading to behaviours of unintentional academic misconduct. Importantly, this review includes practical suggestions to help educators and higher education institutions support doctoral students’ academic integrity skills. In particular, the authors highlight the importance of explicit academic integrity instruction, support for the development of academic literacy skills, and changes in supervisory practices that encourage student and supervisor reflexivity. Therefore, this review argues that, through the use of these practical strategies, academia can become a space where a culture of academic integrity can flourish.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the contemporary higher education environment, issues of academic integrity and credibility are turning matters of learning into matters of surveillance and enforcement. Increasingly, higher education institutions are relying on text-matching software (such as Turnitin) and the monitoring or scrutiny of students (e.g., through practices such as online proctoring) as a proxy to measure their level of academic integrity (Dawson 2021). Indeed, failure to adhere to these often contextually and socially constructed rules of academic integrity is termed academic misconduct or dishonesty and can lead to severe consequences for students. As Dawson (2021) notes, this approach is adversarial, focussing on detection rather than encouraging academic integrity. This adversarial approach is also reflected in recent changes to Australian federal legislation (see the Prohibiting Academic Cheating Services Act 2020), with provision of an academic cheating service now attracting criminal or civil penalties. There is also increasing concern about the “threats to academic integrity [ …] due to the wide-spread growth of commercial essay services and attempts by criminal actors to entice students into deceptive or fraudulent activity” (Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) 2021 para. 2 emphasis added). Despite this often adversarial language, however, TEQSA also acknowledges that there is a need to promote academic integrity practices by, for example, working with experts to create an Academic Integrity Toolkit (TEQSA 2021).

Interestingly, the higher education environment now appears to lead educators to a dichotomous choice to either be “pro-integrity” or “anti-cheating” (Dawson 2021 p. 3). In this conceptual review, we seek to challenge this perception. We focus on how doctoral education programs can foster academic integrity skills development to create an environment where policies and surveillance strategies are incorporated into pedagogical practice. East (2009) highlights the importance of viewing academic integrity development as a holistic and aligned approach that supports the development of an honest community within the university. Furthermore, Clarence (2020) argues that doctoral education is underpinned by the axiological belief that graduates should be confident scholars who value integrity in research, authenticity, and ethics. Therefore, it is our argument that it is the responsibility of educators to explicitly teach these skills as part of doctoral education programs in order to encourage a culture of academic integrity among both staff and students (see, for example, Nayak et al. 2015; Richards et al. 2016). The long-term benefits of such a culture of academic integrity will include greater awareness of academic integrity for both staff and students, the involvement of students in creating and managing their own academic integrity, a reduction in academic integrity breaches, and improved institutional reputations (Richards et al. 2016).

Contextualising our review within the Australian higher education setting, our view of academia is representative of an all-encompassing global space which welcomes the skills, knowledge, values, and practices of all scholars regardless of their background. In this review, we highlight how practices within academia create an environment where feelings of inadequacy thrive, leading to behaviours of unintentional academic misconduct. In particular, we explore the impact of the imposter phenomenon and cultural differences on academic integrity practices in doctoral education. We conclude this review by providing practical suggestions to help educators and institutions support doctoral student writing in order to avoid forms of unintentional academic misconduct. Therefore, in this review we argue that, through the use of these practical strategies, academia can become a space where a culture of academic integrity can flourish.

Key concepts in academic integrity

As Bretag (2016) stresses, definitions of integrity terms matter, as researchers have previously fallen into the trap of synonymously linking concepts together. The notion of academic integrity is multifaceted and complex, so defining the concept is an ongoing and contestable debate amongst researchers (Bretag 2016). In general, academic integrity is considered the moral code of academia that involves “a commitment to five fundamental values: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, and responsibility” (International Center for Academic Integrity 2014 p. 16). Therefore, we consider academic integrity as a researcher’s investment in, and commitment to, the values of honesty, trust, fairness, respect, and responsibility in the culture of academia. In this review, we adopt the following interpretation of academic integrity (Exemplary Academic Integrity Project 2013 section 15 para. 2):

Academic integrity means acting with the values of honesty, trust, fairness, respect and responsibility in learning, teaching and research. It is important for students, teachers, researchers and all staff to act in an honest way, be responsible for their actions, and show fairness in every part of their work. Staff should be role models to students. Academic integrity is important for an individual’s and a school’s reputation.

An important component of academic integrity for doctoral students is integrity in the research process. We consider ethical research practice to involve conducting research in a fair, respectful and honest manner, and reporting findings responsibly and honestly.

In contrast, academic misconduct (also termed academic dishonesty) involves behaviours that are contrary to academic integrity, most notably plagiarism, collusion, cheating, and research misconduct. In this review, plagiarism refers to presenting someone else’s published work as your own without appropriate attribution. Drawing on the work of Fatemi and Saito (2020), we stress that plagiarism can be either intentional or unintentional. We consider intentional plagiarism as purposely using other people’s work and promoting it as your own. In contrast, we define unintentional plagiarism as not acknowledging another researchers’ ideas by, for example, forgetting to insert a reference, not inserting the reference for every sentence from a source, or placing the reference in the wrong place within the text (Fatemi and Saito 2020). In this review, collusion is defined as unauthorised collaboration with someone else on assessed tasks while cheating is defined as seeking an unfair advantage in an assessed task, including resubmission of work from another unit. Notably, academic settings have seen a rise in what has been termed contract cheating, where assignments are completed by outside actors in a fee-for-service type arrangement (Bretag et al. 2019; Bretag et al. 2020; Clarke and Lancaster 2006; Dawson 2021; Newton 2018). Finally, we consider research misconduct to be misrepresenting the study design or methodology, falsifying or fabricating data, and/or breaching ethical research requirements. Academic institutions often have a range of responses, policies, and procedures to identify academic misconduct; these range from official warnings to loss of marks on an assignment or expulsion from the institution for the most severe cases.

Academic integrity and the imposter phenomenon

It is important to note that, for this review, the authors have agreed upon the term imposter phenomenon, although the expression imposter syndrome is often used synonymously in the literature. The term imposter syndrome was initially coined by Clance and Imes (1978) to describe individuals who felt like frauds and perceived themselves as unworthy of their achievements, despite objective evidence to the contrary. To avoid stigmatisation of these feelings as a pathological syndrome, the term imposter phenomenon is more commonly used in modern thinking. Imposter phenomenon can therefore be defined as “the persistent collection of thoughts, feelings and behaviours that result from the perception of having misrepresented yourself despite objective evidence to the contrary” (Kearns 2015 p. 25).

This notion of feeling like a fraud is frequently experienced by doctoral students. Indeed, half (50.6%) of the PhD students in the study by Van de Velde et al. (2019) reported experiencing the imposter phenomenon. Similarly, Wilson and Cutri (2019) revealed how novice academics experienced constant disbelief in their success. This is because the imposter phenomenon is linked to an identity crisis which is commonly experienced by novice academics (Wilson and Cutri 2019). For instance, Lau’s (2019) autoethnographic reflection as a medical doctoral student highlighted how self-imposed pressures during his PhD journey led to feelings of inadequacy. This was due to a prevailing perception of what “the perfect PhD student” was and the feeling that he was not meeting this perceived standard, leading to self-sabotaging behaviours (Lau 2019 p. 52). Thus, from a doctoral student perspective, Lau (2019 p. 50) defines the imposter phenomenon as:

feelings of inadequacy experienced by those within academia that indicate a fear of being exposed as a fraud. These feelings are not ascribed to external measures of competence or success (e.g., publishing papers or winning prizes), but internal feelings of not being good enough for their chosen role (e.g., being a PhD student or academic staff member).

Lau (2019) warns that, if these feelings are left unchecked, it could lead to low self-confidence and high anxiety.

The imposter phenomenon is increasingly recognised as a significant issue by higher education institutions, but this is often considered a mental health concern affecting productivity and success (see, for example, University of Cambridge 2021; University of Waterloo 2021). It is important to note, though, that the feelings of fraudulence and negative self-confidence can be attributed to the socio-political and cultural environment of academia in which doctoral students are immersed. As Hutchins (2015) notes, the imposter phenomenon thrives in environments where there are expectations of perfectionism, highly competitive work cultures, and stressful environments. Academia is a high-stakes, competitive environment where a person’s success is measured by the quantity and quality of their research output, commonly referred to as an environment of publish or perish. Indeed, Moosa (2018) notes that academics must obey the rules of the publish or perish environment if they are to progress through their career. With an emphasis on scholarly dissemination, doctoral students are thrown into a new context of public critique through the peer review and publication process. While this is an opportunity for academics to showcase their research, Parkman (2016) notes that such public scrutiny invokes the common imposter phenomenon fear of being found out as a fraud. This is because doctoral candidates are constantly exposed to the final product, while the process of writing has been devalued (Wilson and Cutri 2019). The doctoral journey, however, should be about the process, as candidates are developing their skills and building their academic identities as future researchers in their fields.

When academic institutions focus on polished products, doctoral students who are currently engaged in the writing process feel a sense they are not good enough (Wilson and Cutri 2019). This is because the writing process and expectations at doctoral level are complex and challenging, requiring students to develop specific academic skill sets that are different from their previous studies (see Level 10 of the Australian Qualifications Framework for a list of the expected skills of doctoral graduates in Australia, Australian Qualifications Framework Council 2013). Facing these new challenges can be overwhelming and students compensate by engaging in sabotaging behaviours (such as procrastination, perfectionism, or avoidance) because they feel they must write like the experts in their field. Cisco (2020a) found that imposter phenomenon feelings became more prevalent with the challenge of these new and more complex academic tasks. This struggle during the reading and writing process can be attributed to a need for further development of the necessary academic literacy skills for a specific discipline. In this review, we consider literacy to refer to the socially constructed use of language within a particular context (Barton and Hamilton 2012; Lea 2004; Lea and Street 1998, 2006; Street 1984, 1994). Consequently, it is important to note that literacy is continuously constructed and includes elements of both power and privilege (Lea 2004; Lea and Street 1998, 2006). The term academic literacy skills, therefore, reflect a broad range of practices that are involved in the practice of communicating scholarly research (for example, learning the differences in academic writing for literature reviews, methodology, data analysis, and discussion of findings sections to answer the all-important so what question). These more advanced academic literacy skills are relatively new aspects for doctoral students, as the production of new knowledge is what makes a PhD candidature unique.

When doctoral students commence their studies, they transfer their prior understandings regarding appropriate academic conduct. Students enter doctoral training programs through a variety of pathways. For example, some students enter a PhD after completing an Honours degree, while others first complete a Masters or other graduate research degree. Increasingly, doctoral programs are also seeing students who return to study after several years away from university. Hence, students who enter doctoral studies, regardless of their prior educational experience, bring their discourses of academic understanding and what they perceive as appropriate with them.

It is likely that doctoral students have, at some point in their studies, encountered the concept of academic integrity at some level. While students may have encountered the concept of academic integrity in the past, this previous knowledge does not necessarily translate into an understanding of how to demonstrate academic integrity in their work at a doctoral level. There are also institutional and cultural differences that play a significant part in how academic integrity is applied in practice. Understanding how to apply this academic integrity knowledge in academic writing practice should, therefore, be considered a threshold concept – it is a concept which, when understood, leads to a permanent change of perspective (see Meyer and Land 2006). Pretorius and Ford (2017) describe threshold concepts as “gatekeepers to deeper knowledge, understanding and thinking [ …] that allow students to genuinely see new perspectives and think in different ways” (p. 151). Tyndall et al. (2019) notes that if doctoral students do not move across the threshold to understand how to apply academic integrity in their writing, it can lead to academic misconduct behaviours including mimicry and plagiarism.

Mimicking the sophisticated genre of academic writing seen in published works is often done in an effort to sound academic. The disciplinary discourse in which a person finds themselves contributes to the social construction of identity (Ivanič 1998). Furthermore, a person’s identity is inscribed in their writing practices (Ivanič 1998) – we write ourselves into our text as we interact with the social context in which we find ourselves. Ivanič (1998) notes that this discursive identity construction provides a useful lens through which to view academic integrity. Instead of condemning students for academic integrity breaches such as plagiarism, Ivanič (1998) argues that this type of behaviour can be seen as a function of “students’ struggles to achieve membership of the academic discourse community” (p. 197). For example, Fatemi and Saito (2020) note that, in the absence of appropriate academic literacy skills, postgraduate students can engage in what Howard (1992) termed patchwriting (i.e., poor paraphrasing, also termed source-reliant composition) where some words are synonymously replaced while the original sentence structure is maintained. While such an action is deemed as plagiarism, the students’ intentions are usually not to cheat but rather to try and write in what they perceive to be an academic style (Fatemi and Saito 2020; Pecorari 2003). Consequently, if doctoral students, engage in a form of academic misconduct other than contract cheating, we argue this is a form of unintentional academic dishonesty.

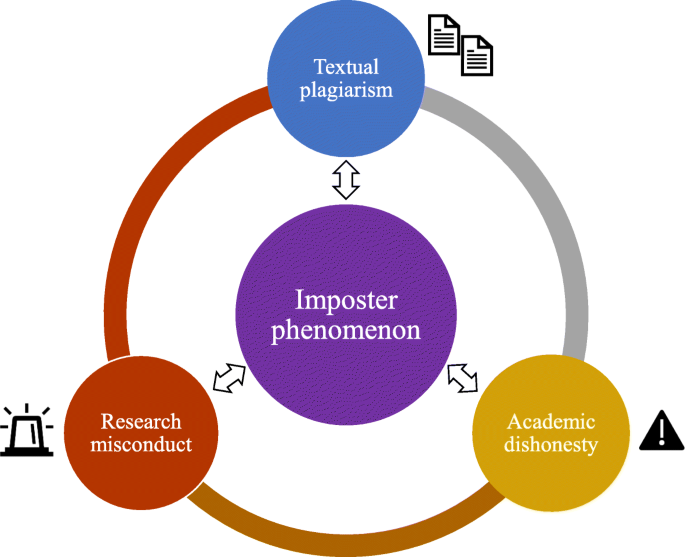

We have developed a model to highlight how the imposter phenomenon influences doctoral students’ academic integrity which we have termed the IPAIR model (the imposter phenomenon and academic integrity relationship model, see Fig. 1). We argue that feelings of being discovered as a fraud lead students to mimic academic practices, including textual plagiarism, academic dishonesty, and research misconduct (Fig. 1). The first component of this model, textual plagiarism, involves taking credit for another person’s published work without referencing the source, by providing inaccurate citation details, or by engaging in poor paraphrasing such as patchwriting. The second component, academic dishonesty, consist of the other elements of academic misconduct such as reusing previous work, collusion, and contract cheating. The final component of our model, research misconduct, includes misrepresenting the study design or methodology, falsifying or fabricating data, and breaching ethical requirements. It is important to note that the academic integrity breaches in our model are not necessarily intentional. Furthermore, it should be noted that the forms of academic misconduct highlighted in our model would also likely further exacerbate doctoral students’ feelings of inadequacy.

Academic integrity and cultural differences

We have argued that there is a relationship between the imposter phenomenon and academic integrity in relation to doctoral student writing. We further contend that cultural differences may impact academic integrity during a doctoral student’s candidature. In Australia, domestic and international students from a wide variety of cultural backgrounds study PhDs (see, for example, Cutri and Pretorius 2019; Pretorius and Macaulay 2021). In this paper we define a domestic student as someone who is an Australian or New Zealand citizen, or who holds a permanent residency or humanitarian visa. The term international student refers to someone who has a temporary visa to study in Australia. It is important to note that, in using the terms domestic and international, we do not intend to create a dichotomy between these student cohorts. Rather, these two terms can be considered representative of the often-times different sociocultural characteristics and power relationships that influence these students’ experiences (Cutri and Pretorius 2019; Pretorius and Macaulay 2021). It is also important to note that cultural differences exist between domestic students as well.

Today’s contemporary research context reflects a globalised academic landscape comprising expert, early career, and novice academics. The increase of internationally diverse doctoral scholars can be attributed to the process of globalisation (Cutri and Pretorius 2019). For this review, we have chosen to draw upon Holton’s (2005) definition of globalisation: “the intensified movement of goods, money, technology, information, people, ideas and cultural practice across political and cultural boundaries” (pp. 14–15). Globalisation has impacted higher education through an increased movement of international students which has also resulted in a higher number of international doctoral students enrolling at higher education institutions (Cutri and Pretorius 2019; Marginson and van der Wende 2007; Nerad 2010). In fact, many universities promote the mobility of higher education and offer scholarships for people around the world to continue their studies. This has led to the emergence of various cultural differences in expectations and understandings of academic integrity causing universities to reconsider their academic integrity practices and support structures for students.

Importantly, globalised movements describe not only people migrating from one country to another but also the movement of people’s ideas, beliefs and culture (see, for example, Appadurai 1990). Culture offers a lens through which people see and understand the world in which they live (Garcia and Dominguez 1997). Hence, culture includes “shared values, beliefs, perceptions ideals, and assumptions about life that guide specific behaviour” (Garcia and Dominguez 1997 p. 627). Hofstede et al. (2010) state that culture programs people’s behaviour, reaction and understanding and thus call it the “software of the mind” (p. 5). Culture is dynamic, persists over time, and, therefore, guides an individual’s capacity to make meaning of their world and experiences (Garcia and Dominguez 1997). Most importantly, Bourdieu (1984) argues that people can be unaware of their own cultural influences and how it shapes their decisions. Thus, the cultural practices, values and beliefs guiding an individual’s decisions appear natural and intuitive, but are in fact culturally driven. Consequently, culture plays a crucial role in influencing and guiding an individual’s decisions and meaning making capacity.

Cultural difference can be a leading cause for academic dishonesty amongst international postgraduate students as academic integrity has different definitions for different cultures (Velliaris and Breen 2016). This highlights that international postgraduate students may have different standards of academic integrity and plagiarism than the domestic students at their host universities. Students bring their pre-existing beliefs into academia while they, at the same time, grapple with newly formed expectations to be experts in their fields (see, for example, Cutri 2019). Indeed, as authors of this literature review, we found that we had several different pre-existing beliefs of academic integrity due to our own cultural backgrounds. For example, one of the authors of this literature review notes:

While in Australia, especially in doctoral studies, one of the key functions of an academic is to contribute to knowledge by identifying and filling gaps in existing knowledge. This requires advanced yet complex skills in reading existing literature, questioning the ontological and epistemological existence of knowledge along with arguing or critiquing studies respectfully. As an individual, who has experienced the [education system in my country] that worship textbooks, I find it extremely challenging to critique other studies and fail to recognise the limitations in the findings, methodology or methods employed in the study. Culturally, this practice of reviewing other academics work and addressing the limitations and gaps was not preached, experienced or expected. Therefore, I tend to use a lot of direct quotes from original writing.

As highlighted above, an array of cultural differences exists in understanding academic integrity. These differences in academic expectations can be wide-reaching, including a lack of language proficiency, as well as an unfamiliarity with the myriad of research and writing practices of their host universities (Cisco 2020a; Fatemi and Saito 2020). These differences can negatively affect postgraduate international students’ transition into academia, potentially leading to academic dishonesty (Fatemi and Saito 2020). It is, therefore, hardly surprising that Bretag et al. (2014) found that international students received three times more formal notifications of academic integrity breaches compared with domestic students. International students were also more than twice as likely to report feeling ill-prepared to avoid academic integrity breaches (Bretag et al. 2014).

Another factor resulting in a lack of academic integrity from international doctoral students is believed to be the lack of academic support for these students (Fatemi and Saito 2020). The transition from their home country’s academic integrity practices to those of their host country can also mean that not all skills brought by international postgraduate students are recognised by the host university. The transfer between one educational system to another combined with a lack of familiarity with the local academic integrity practices can result in unintentional academic dishonesty by international students (Fatemi and Saito 2020). Without appropriate support to develop academic skills from their universities, postgraduate international students can develop negative opinions about host countries and feel that their prior academic skills are devalued. It is, therefore, imperative that international postgraduate students adapt to local academic integrity practices with the support of universities. It is equally vital that local universities honour and value the pre-existing skills and beliefs of doctoral students and assist these students with building a new set of academic integrity practices.

Building academic integrity at a doctoral level

In the previous sections, we have highlighted the influence of the impostor phenomenon, a lack of academic literacy skills, and cultural differences on the academic integrity practices of doctoral students. Based on these factors, this section explores the multifaceted measures that could be put in place to better support doctoral students in developing academic integrity in their research and writing practices. In particular, we highlight the importance of explicit academic integrity instruction, support for academic literacy development, and changes in supervisory practices.

Explicit academic integrity instruction

The key to improved academic integrity practices at any level of study is the understanding of appropriate conventions in the discipline. Once PhD students are enrolled in their studies, many Australian universities provide mandatory training components related to academic integrity in research. At our institution, for example, all doctoral students are required to complete three online doctoral induction models that cover an introduction to the University, the Faculty, and research integrity. Across institutions, however, research integrity training is offered in a variety of formats and are focussed on many different areas of research ethics. Furthermore, there appears to be a presumption that, upon completion of these modules, doctoral students will understand their responsibilities and, therefore, not engage in academic misconduct. We argue that this presumption is dangerous and that doctoral students require ongoing scaffolding and skills development throughout their candidature. Furthermore, as highlighted in our model (see Fig. 1), research integrity involves a specific skill set. A lack of understanding of this skill set can lead to academic misconduct if students are not adequately supported. Löfström and Pyhältö (2017) highlight that doctoral students rely on their supervisors and faculty colleagues to help learn ethical guidelines and appropriate codes of conduct. By acknowledging that doctoral students unintentionally engage in academic misconduct due to a lack of awareness, universities can offer supportive structures and educational programs to help foster a deeper understanding of the impact of the imposter phenomenon, academic literacy skills, and ethical research approaches.

Bretag et al. (2014) highlight that postgraduate research students can be disadvantaged in terms of education, training, and support for academic integrity. This calls for institutions to provide interventions in the form of direct instruction at different stages of a doctoral program. Gullifer and Tyson (2014) have highlighted the need for universities to take proactive steps by offering formal workshops that highlight the expectations and strategies to maintain academic integrity rather than expecting students to read academic integrity policies. Fatemi and Saito (2020) have also called for a more standardised approach to teaching academic integrity, including attention to the practical skills associated with citation, paraphrasing, and summarising. The skill of referencing is usually taught at the undergraduate level, so there is often the expectation that postgraduate students have acquired this knowledge in their undergraduate studies and are consequently able to reference correctly. However, a lack of awareness can be attributed to several factors, such as changing disciplinary or cultural conventions. A more nuanced understanding of referencing conventions should, therefore, be explicitly taught, particularly at the start of a doctoral student’s candidature.

Academic integrity software can also be used in a more educative manner to help scaffold students’ understanding. In our Faculty, for example, the text-matching software Turnitin is used to help doctoral students improve their approaches to academic integrity prior to submission of written work to their supervisors, academic publishers, or thesis examiners. This practice version of a Turnitin dropbox emphasises the use of the software as a learning tool, rather than a surveillance strategy, enabling students to discover where they have engaged in poor paraphrasing. While anecdotal, our experience seems to indicate that this approach, in conjunction with educational videos, tutorials, and educator guidance, can scaffold doctoral students’ understanding of academic integrity according to disciplinary conventions. This form of explicit instruction can be provided throughout a student’s doctoral journey, in order to raise an awareness of academic integrity practices as well as lay a solid foundation for the student’s future study and career.

Another consideration is that doctoral students may come from a different cultural academic context where different writing practices are valued. In designing and implementing these interventions, we consequently argue that academic integrity training should not only target the implementation of research integrity codes from above (Sarauw et al. 2019). We believe that the training should also be a site for doctoral students to negotiate, question, and affirm institutional codes in order to develop their individual reflexivity and responsibility as junior academics (Sarauw et al. 2019). By allowing reflection on professional practice, educators and supervisors will provide a space for doctoral students to discover and apply appropriate integrity practices. It is also important to note that, as Hyytinen and Löfström (2017) highlight, academic staff may also require pedagogical training on how to effectively teach research integrity and ethics. Targeting these interventions at both institutional and individual levels could help to create an institution which supports, facilitates, and provides a conducive environment for academic integrity where reflexive and responsible researchers can flourish.

Support for academic literacy development

Building confidence in writing ability by modelling the writing process is an important way to scaffold academic integrity for PhD students. Fatemi and Saito (2020) noted that a lack of self-confidence and lack of knowledge in relation to academic literacy skills were key causes of plagiarism. Cisco (2020b) also reported that literacy interventions that target academic and disciplinary literacy, in addition to reading and writing academic texts, can help doctoral students develop the academic skill set required to thrive in academia. Emerson et al. (2005) highlighted that a lack of academic integrity in students’ writing is often a consequence of a lack of understanding of the academic writing process. Experienced academic writers, however, realise that academic writing is indeed a process (Wilson and Cutri 2019). For instance, manuscripts often undergo multiple revisions and significant editing prior to submission for publication. Peer review then leads to further changes before final publication. Modelling this process for students can be an eye-opening experience, helping students overcome some of the feelings associated with writing anxiety and the imposter phenomenon (see, for example, the experiences of Lam et al. 2019).

Consequently, we advocate for the establishment of learning communities such as writing groups. Doctoral writing groups offer a safe and low-risk environment where students can build their academic writing skills in a peer learning environment (Aitchison and Guerin 2014; Cahusac de Caux et al. 2017). It has been shown that the peer feedback component of these types of writing groups helps students to build their writing confidence, foster greater reflective practice, and encourage them to take ownership of their writing style (Cahusac de Caux et al. 2017; Lam et al. 2019). Encouraging doctoral students to join, or indeed set up their own, learning communities could, therefore, significantly improve students overall learning experience during their candidature. It is important to note, however, that students often tend to seek peer support from fellow students who come from a similar cultural or linguistic background. Accordingly, it is important to consider how the benefits of writing groups with members from a variety of backgrounds and perspectives can be best showcased to students.

Changes in supervisory practices

We believe that the supervision process should enable students to develop their academic integrity. The role of a research supervisor is crucial in doctoral students’ academic endeavours. Supervision entails an enculturation function in which students are encouraged to be a member of the disciplinary community in academia through role-modelling and apprenticeship (Lee and Murray 2015). This can be achieved through exposure to exemplary texts to analyse, encouragement for students to produce their own texts based on these exemplars, and provision of advice and constructive feedback on students’ writing.

In addition, supervision should also enable emancipation where students are encouraged to develop and question themselves and their motivation in writing (Lee and Murray 2015). This aspect is particularly important, as a doctoral student’s identity changes during the writing process (Clarence 2020; Cotterall 2011). Supervisors should, therefore, motivate students to reconceptualise writing not just as a method of completing a thesis, but also as a learning process. As noted by Pretorius (2019 p. 5),

the doctoral journey is more than just a three- to four-year timeframe where a student eventually submits a thesis as evidence of the creation of new knowledge. Rather, the doctoral experience incorporates a variety of opportunities for more in-depth personal development, particularly in terms of intrapersonal wellbeing, academic identity and sense of agency, as well as intercultural competence.

To facilitate this more in-depth personal development, writing tasks from supervisors should be more diverse. This is in line with postmodern scholars’ conception of writing as a method of inquiry (Richardson 2000; Richardson and St. Pierre 2005; St. Pierre 1997). Writing can be a method of self-discovery to explore doctoral students’ deepest desires in undertaking their doctoral projects and consequently their motivation in writing. Pretorius and Cutri (2019) provide a framework for doctoral student reflection based on the “What? So What? Now What” reflective practice model (see also Driscoll 2000; Rolfe et al. 2001) that can help doctoral students explore their experiences during their doctoral candidature. As guiding prompts to write about their writing process, Fernsten and Reda (2011) have also provided 35 questions that can help doctoral students become reflexive writers who can critically identify problems with their writing and texts. This shift to a more reflective approach can reduce writing anxiety because, instead of viewing writing as a high-stakes activity, writing is conceptualised as thinking, analysis, and as “a seductive and tangled method of discovery” (Richardson and St. Pierre 2005 p. 1423).

Conclusion

In this conceptual literature review, we have explored the key factors that are associated with academic integrity in doctoral education. We argue throughout this article that academic misconduct within doctoral studies is underpinned by two significant factors: the imposter phenomenon and cultural differences. Facing these challenges can be overwhelming for doctoral students, which we argue can lead to unintentional academic misconduct. We, therefore, emphasise that approaches ensuring academic integrity do not need to be adversarial or geared towards merely surveillance and punishment. Rather, an educative approach can help to create a culture of academic integrity in the doctoral education setting. We provide practical suggestions to help institutions support doctoral student writing in order to avoid unintentional academic misconduct. In particular, we highlight the importance of explicit academic integrity instruction, support for the development of academic literacy skills, and changes in supervisory practices that encourage student and supervisor reflexivity. We argue that, through the use of these practical strategies, academia can become a space where a culture of academic integrity can flourish.

Availability of data and materials

This literature review is based on analyses of published peer-reviewed research using standard word processing, annotation, and referencing software. No additional data were collected or analysed. No custom software or codes were used to conduct analyses.

Abbreviations

- IPAIR model:

-

Imposter phenomenon and academic integrity relationship model

- TEQSA:

-

Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency

References

Aitchison C, Guerin C (2014) Writing groups for doctoral education and beyond: innovations in practice and theory. Routledge, New York

Appadurai A (1990) Disjuncture and difference in the global cultural economy. Theor Cult Soc 7(2–3):295–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/026327690007002017

Australian Qualifications Framework Council (2013) Australian qualifications framework (AQF) second edition. www.aqf.edu.au.

Barton D, Hamilton M (2012) Local literacies: Reading and writing in one community. Routledge, London

Bourdieu P (1984) Distinction: a social critique of the judgement of taste. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Bretag T (2016) Educational integrity in Australia. In: Bretag T (ed) Handbook of academic integrity. Springer, Singapore, pp 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-098-8_2

Bretag T, Harper R, Burton M, Ellis C, Newton P, Rozenberg P, Saddiqui S, van Haeringen K (2019) Contract cheating: a survey of Australian university students. Stud High Educ 44(11):1837–1856. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1462788

Bretag T, Harper R, Rundle K, Newton PM, Ellis E, Saddiqui S, van Haeringen K (2020) Contract cheating in Australian higher education: a comparison of non-university higher education providers and universities. Assess Eval High Educ 45(1):125–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1614146

Bretag T, Mahmud S, Wallace M, Walker R, McGowan U, East J, Green M, Partridge L, James C (2014) ‘Teach us how to do it properly!’: An Australian academic integrity student survey. Stud High Educ 39(7):1150–1169. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.777406

Cahusac de Caux BKCD, Lam CKC, Lau R, Hoang CH, Pretorius L (2017) Reflection for learning in doctoral training: writing groups, academic writing proficiency and reflective practice. Reflect Pract 18(4):463–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2017.1307725

Cisco J (2020a) Exploring the connection between impostor phenomenon and postgraduate students feeling academically-unprepared. High Educ Res Dev 39(2):200–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1676198

Cisco J (2020b) Using academic skill set interventions to reduce impostor phenomenon feelings in postgraduate students. J Furth High Educ 44(3):423–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2018.1564023

Clance PR, Imes, SA (1978) The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychother Theor Res Pract 15(3):241-247. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0086006

Clarence S (2020) Making visible the affective dimensions of scholarship in postgraduate writing development work. J Prax High Educ 2(1):46–62

Clarke R, Lancaster T (2006) Eliminating the successor to plagiarism? Identifying the usage of contract cheating sites. In: the Proceedings of the 2nd plagiarism: prevention, practice and policy conference, Newcastle, United Kingdom, JISC plagiarism advisory service

Cotterall S (2011) Doctoral students writing: where's the pedagogy? Teach High Educ 1(4):413–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2011.560381

Cutri J (2019) The third space: Fostering intercultural communicative competence within doctoral education. In: Pretorius L, Macaulay L, Cahusac de Caux B (eds) Wellbeing in doctoral education: Insights and guidance from the student experience. Springer, Singapore, pp 265–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9302-0_22

Cutri J, Pretorius L (2019) Processes of globalisation in doctoral education. In: Pretorius L, Macaulay L, Cahusac de Caux B (eds) Wellbeing in doctoral education: Insights and guidance from the student experience. Springer, Singapore, pp 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9302-0_17

Dawson P (2021) Defending assessment security in a digital world: preventing e-cheating and supporting academic integrity in higher education. Routledge, New York. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429324178

Driscoll J (2000) Practising clinical supervision: a reflective approach. Baillière Tindall Elsevier, Edinburgh

East J (2009) Aligning policy and practice: an approach to integrating academic integrity. J Acad Lang Learn 3(1):A38–A51

Emerson L, Rees M, MacKay B (2005) Scaffolding academic integrity: creating a learning context for teaching referencing skills. J Univ Teach Learn Pract 2(3):12–24

Exemplary Academic Integrity Project (2013) Embedding and extending exemplary academic integrity policy and support frameworks across the higher education sector. Plain English definition of academic integrity. Office for Learning and Teaching Strategic Commissioned Project, Adelaide

Fatemi G, Saito E (2020) Unintentional plagiarism and academic integrity: the challenges and needs of postgraduate international students in Australia. J Furth High Educ 44(10):1305–1319. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1683521

Fernsten LA, Reda M (2011) Helping students meet the challenges of academic writing. Teach High Educ 16(2):171–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2010.507306

Garcia SB, Dominguez L (1997) Cultural contexts which influence learning and academic performance. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 6(3):621–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1056-4993(18)30298-0

Gullifer JM, Tyson GA (2014) Who has read the policy on plagiarism? Unpacking students' understanding of plagiarism. Stud High Educ 39(7):1202–1218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.777412

Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ, Minkov M (2010) Cultures and organizations: software of the mind: intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival. McGraw-Hill, New York

Holton RJ (2005) Making globalisation. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Howard RM (1992) A plagiarism pentimento. J Teach Write 11(2):233–245

Hutchins HM (2015) Outing the imposter: a study exploring imposter phenomenon among higher education faculty. New Horiz Adult Educ Hum Resour Dev 27(2):3–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/nha3.20098

Hyytinen H, Löfström E (2017) Reactively, proactively, implicitly, explicitly? Academics’ pedagogical conceptions of how to promote research ethics and integrity. J Acad Ethics 15(1):23–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-016-9271-9

International Center for Academic Integrity (2014) The fundamental values of academic integrity. International Center for Academic Integrity, Des Plaines

Ivanič R (1998) Writing and identity: the discoursal construction of identity in academic writing. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam

Kearns H (2015) The imposter syndrome: why successful people often feel like frauds. ThinkWell, Adelaide

Lam CKC, Hoang CH, Lau RWK, Cahusac de Caux B, Tan QQ, Chen Y, Pretorius L (2019) Experiential learning in doctoral training programmes: fostering personal epistemology through collaboration. Stud Contin Educ 41(1):111–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2018.1482863

Lau RWK (2019) You are not your PhD: Managing stress during doctoral candidature. In: Pretorius L, Macaulay L, Cahusac de Caux B (eds) Wellbeing in doctoral education: Insights and guidance from the student experience. Springer, Singapore, pp 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9302-0_6

Lea MR (2004) Academic literacies: a pedagogy for course design. Stud High Educ 25(6):739–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/0307507042000287230

Lea MR, Street BV (1998) Student writing in higher education: an academic literacies approach. Stud High Educ 23(2):157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079812331380364

Lea MR, Street BV (2006) The “academic literacies” model: theory and applications. Theor Pract 45(4):368–377. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4504_11

Lee A, Murray R (2015) Supervising writing: helping postgraduate students develop as researchers. Innov Educ Teach Int 5(5):558–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2013.866329

Löfström E, Pyhältö K (2017) Ethics in the supervisory relationship: supervisors’ and doctoral students’ dilemmas in the natural and behavioural sciences. Stud High Educ 42(2):232–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1045475

Marginson S, van der Wende M (2007) Globalisation and higher education. In: OECD education working papers, No. 8. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/173831738240

Meyer JHF, Land R (2006) Overcoming barriers to student understanding: threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge. Routledge, London

Moosa IA (2018) Publish or perish: perceived benefits versus unintended consequences. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, Cheltenham

Nayak A, Richards D, Homewood J, Taylor M, Saddiqui S (2015) Academic integrity in Australia - understanding and changing culture and practice. Office for Learning and Teaching, Department of Education and Training, Sydney

Nerad M (2010) Globalisation and the internationalisation of graduate education: a macro and micro view. Can J High Educ 40(1):1–12

Newton PM (2018) How common is commercial contract cheating in higher education and is it increasing? A systematic review. Front Educ 3:1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00067

Parkman A (2016) The imposter phenomenon in higher education: incidence and impact. J Furth High Educ 16(1):51–61

Pecorari D (2003) Good and original: plagiarism and patchwriting in academic second-language writing. J Sec Lang Write 12(2003):317–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2003.08.004

Pretorius L (2019) Prelude: The topic chooses the researcher. In: Pretorius L, Macaulay L, Cahusac de Caux B (eds) Wellbeing in doctoral education: Insights and guidance from the student experience. Springer, Singapore, pp 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9302-0_1

Pretorius L, Cutri J (2019) Autoethnography: Researching personal experiences. In: Pretorius L, Macaulay L, Cahusac de Caux B (eds) Wellbeing in doctoral education: Insights and guidance from the student experience. Springer, Singapore, pp 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9302-0_4

Pretorius L, Ford A (2017) Mind-melds and other tricky business: teaching threshold concepts in mental health preservice training. In: Kendal E, Diug B (eds) Teaching medicine and medical ethics using popular culture (Palgrave studies in science and popular culture). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, pp 149–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65451-5_9

Pretorius L, Macaulay L (2021) Notions of human capital and academic identity in the PhD: Narratives of the disempowered. J High Educ:1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2020.1854605

Richards D, Saddiqui S, White F, McGuigan N, Homewood J (2016) A theory of change for student-led academic integrity. Qual High Educ 22(3):242–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2016.1265849

Richardson L (2000) Writing: a method of inquiry. In: Denzin N, Lincoln YS (eds) The handbook of qualitative research, 2nd edn. SAGE, Thousand Oaks, pp 923–948

Richardson L, St. Pierre EA (2005) Writing: a method of inquiry. In: Denzin N, Lincoln YS (eds) The handbook of qualitative research, 3rd edn. SAGE, Thousand Oaks, pp 1410–1444

Rolfe G, Freshwater D, Jasper M (2001) Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: a user's guide. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Sarauw L, Degn L, Ørberg JW (2019) Researcher development through doctoral training in research integrity. Int J Acad Dev 24(2):178–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2019.1595626

St. Pierre EA (1997) Circling the text: nomadic writing practices. Qual Inq 3(4):403–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780049700300403

Street BV (1984) Literacy in theory and practice. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Street BV (1994) What is meant by local literacies? Lang Educ 8(1–2):9–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500789409541372

Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) (2021). Academic integrity toolkit. https://www.teqsa.gov.au/academic-integrity-toolkit

Tyndall DE, Flinchbaugh KB, Caswell NI, Scott ES (2019) Threshold concepts in doctoral education: a framework for writing development in novice nurse scientists. Nurse Educ 44(1):38–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000000535

University of Cambridge (2021). University counselling service student counselling: Imposter syndrome. https://www.counselling.cam.ac.uk/GroupsAndWorkshops/copy_of_studentgroups/Impsyn

University of Waterloo (2021). Imposter phenomenon and graduate students. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/teaching-resources/teaching-tips/planning-courses/tips-teaching-assistants/impostor-phenomenon-and

Van de Velde J, Levecque K, Mortier A, De Beuckelaer A (2019) Why PhD students in Flanders consider quitting their PhD (ECOOM brief no. 20). Expertisecentrum Onderzoek en Ontwikkelingsmonitoring, Belgium

Velliaris D, Breen P (2016) An institutional three-stage framework: elevating academic writing and integrity standards of international pathway students. J Int Stud 6(2):565–587

Wilson S, Cutri J (2019) Negating isolation and imposter syndrome through writing as product and as process: The impact of collegiate writing networks during a doctoral program. In: Pretorius L, Macaulay L, Cahusac de Caux B (eds) Wellbeing in doctoral education: Insights and guidance from the student experience. Springer, Singapore, pp 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9302-0_7

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prasadi Hatanwila for helpful discussions during the development of this manuscript.

Notes on Contributors

Jennifer Cutri

Email: jennifer.cutri@monash.edu

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5328-5332

Twitter: @jenni_cutri

Jennifer Cutri is a current PhD student in the Faculty of Education at Monash University in Australia. She holds qualifications in Primary Education and Literacy Support. She has worked as a teacher and researcher across schools in Australia and Hong Kong. Jennifer teaches undergraduate and postgraduate students. Her interests involve international education and teacher and learner identity development within intercultural contexts.

Amar Freya

Email: amar.freya@monash.edu

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2147-6959

Twitter: @DrAmarFreya

Dr. Amar Freya recently completed their PhD in which they examined how the experiences of family violence in the Indian-Australian community are understood and how victim survivors seek formal and informal help from More Knowledgeable Others. Amar is passionate about ending gender-based violence and their interests involve research and policy surrounding gender-based violence, intersectionality, gender performativity and promoting a lived experience framework with a particular focus on honouring victim survivors' stories.

Yeni Karlina

Email: yeni.karlina@monash.edu

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6989-2516

Twitter: @hey_yeniii

Yeni Karlina is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Education at Monash University in Australia. She has worked as an English teacher, research assistant, and teacher educator in Indonesia. Her PhD project is on how English teachers’ professional learning experiences in a standardised teacher education program in Indonesia influence their teaching practices and identity development.

Sweta Vijaykumar Patel

Email: sweta.patel@monash.edu

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9363-9262

Twitter: @SwetaVijaykumar

Sweta Vijaykumar Patel is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Education at Monash University in Australia. She is a kindergarten teacher and holds qualifications in Early Childhood Education. Sweta has worked in the field of Early Childhood Education in various capacities in both India and Australia. Currently, Sweta teaches undergraduate students and her research interests involve immigrant educators, as well as culture and pedagogy in diverse early childhood education contexts.

Mehdi Moharami

Email: mehdi.moharami@monash.edu

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6435-8501

Twitter: @MoharamiMehdi

Mehdi Moharami is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Education at Monash University in Australia. He holds qualifications in English Translation and Teaching English. He researches the social and cultural impacts of learning English on learners’ identity negotiation and his areas of interest include language education, culture, identity, and social practices.

Shaoru Zeng

Email: shaoru.zeng@monash.edu

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8884-0968

Shaoru Zeng is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Education at Monash University in Australia. She works as a research assistant and a teacher who teaches students from early childhood to secondary school in Australia. She has a qualification in Education and her research interests include the Australian Curriculum, the International Baccalaureate, as well as Asia studies.

Elham Manzari

Email: elham.manzari@monash.edu

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2323-5614

Twitter: @elliemanzari

Elham Manzari is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Education at Monash University in Australia. She holds qualifications in Education and TESOL and has worked as an IB MYP curriculum director. Elham teaches undergraduate students at Monash University and her research interests include digital technologies in teaching and curriculum, digital sociology, and the philosophy of technology.

Dr Lynette Pretorius

Email: lynette.pretorius@monash.edu

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8998-7686

Twitter: @dr_lpretorius

Dr. Lynette Pretorius is the Academic Language and Literacy Advisor for the Faculty of Education at Monash University in Australia. She works with undergraduate, postgraduate, and graduate research students to improve their academic language and literacy skills. She has qualifications in Medicine, Science, Education, as well as Counselling, and her research interests include doctoral education, wellbeing, experiential learning, and reflective practice.

Funding

The authors did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors for the preparation or publication of this literature review. Amar Freya received a Monash Graduate Scholarship (Research Training Program) to support their PhD studies. Jennifer Cutri and Sweta Vijaykumar Patel received the Centenary Education Grant from the Graduate Women Victoria Scholarship Program to support their PhD studies. Yeni Karlina, Mehdi Moharami, and Elham Manzari received the Monash Graduate Scholarship and the Monash International Postgraduate Research Scholarship to support their PhD studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jennifer Cutri, Amar Freya, Yeni Karlina, Sweta Vijaykumar Patel, Mehdi Moharami, Shaoru Zeng, and Elham Manzari contributed to the collection, analysis, and synthesis of literature, as well as manuscript preparation, review, and editing. Dr. Lynette Pretorius conceptualized the research project, contributed to the collection, analysis, and synthesis of literature, administered and supervised the research project, validated the data analyses, developed the visualization used in the manuscript, as well as contributed to manuscript preparation, review, and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cutri, J., Freya, A., Karlina, Y. et al. Academic integrity at doctoral level: the influence of the imposter phenomenon and cultural differences on academic writing. Int J Educ Integr 17, 8 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-021-00074-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-021-00074-w