Abstract

The extraction of coal seams from subterranean strata has the potential to induce displacement and deformation within the overlying strata. This leads to fractures in the strata and surface subsidence. The repetitive mining of coal seams, especially in scenarios involving multiple coal seams, can reactivate previously stabilized rock strata, causing them to subside and deform again. This exacerbates deformation and compromises the structural integrity of the strata. Consequently, there is an imperative need to thoroughly investigate the patterns of movement exhibited by overlying rock layers as a result of the recurrent extraction of coal seams. In recent years, significant progress in this field has been the effective utilization of the Influence Function Method-Key Stratum (IFM-KS) hybrid model. This model, distinguished by its amalgamation of mechanical and geometric methodologies, has proven to be efficacious in scrutinizing the movement dynamics of overlying strata in the context of single-layer mining operations. Based on that, this paper introduces a novel model for predicting rock layer movement and deformation in multi-seam mining. The calculation results derived from this model reveal the dynamics of rock layers' movement and deformation following secondary disturbances during repetitive mining. The accuracy and reliability of this newly proposed model in predicting rock movement during dual-layer coal mining are validated through both theoretical calculations and UDEC numerical simulations. The results demonstrate a high degree of consistency between the numerically simulated rock displacement and mathematical calculations and the rationality of the model. Based on the rock strata movement calculation results, the corresponding porosity distribution is also derived. Compared to single-layer coal mining, multi-seam mining could cause greater changes in porosity in the goaf area and extensive damage to rock strata. More fracture pathways between coal seams occur and a volume of air-leakage quantity is expected. This computational model provides invaluable insights for predicting rock strata deformation and porosity distribution in repetitive mining scenarios of a similar nature.

Article highlights

-

A new model is proposed to predict rock movement in multi-seam coal mining.

-

The model integrates key stratum theory and mechanical calculations.

-

It is user-friendly and evaluates both seam displacement and fracture fields.

-

The prediction model is demonstrated through a case study with minimal error.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The extraction of coal seams disrupted the initial stress equilibrium within the overlying strata, inevitably giving rise a range of phenomena, including collapse, bending, subsidence, and strata separation in the overlying rocks layers. These processes resulted in various issues pertaining to ground pressure, surface subsidence, and the seepage of fluids within the rock layers, such as water and gas(Barbato et al. 2016; Ewy and Hood 1984; Gentry and Jr. Abel, 1978; Kumar et al. 2015; Singh et al. 2002).Investigating strata movement has played a pivotal role as the foundational underpinning of scientific mining.

Research on the mechanical behaviors preceding and ensuing the fracturing of rock strata has unveiled intricate patterns governing strata movement, which holds considerable implications for the coal mining industry in terms of safety and operational efficiency (Holla 1997; Moon and Roy 2004; Zhang et al. 2023). Scholars from both domestic and international backgrounds have conducted theoretical investigations and practical applications, resulting in fruitful outcomes.

(Liu 1995) in his exploration of the movement and fracture patterns of overlying strata in goaf areas, introduced the "vertical three zones" and "horizontal three zones" theory, making noteworthy contributions to the study of overlying rock fissure activity. Building upon this (Wu et al. 1997) developed the key stratum theory, focusing on the deformation, separation, and fracture patterns of overlying rocks under the influence of the essential layer. Their methodological approaches included model experiments, image analysis, and discrete element simulations, culminating in the formulation of the "O"-type fissure ring theory.

Moreover, a multitude of scholars have advanced models for strata movement in single-layer coal mining, developed the rock subsidence coefficient model and formulated methodologies for calculating pivotal parameters (Cyrul 1993; Deck et al. 2018; Levinson and Dimitrakopoulos 2023; Poggi et al. 2023). The stochastic medium theory, developed using the probability integration method, has become one of the most widely adopted techniques in subsidence prediction (Li et al. 2017; Sun et al. 2023, 2020). The fracture patterns of overlying strata were analyzed when the roof of a goaf collapsed, establishing the "pseudo-hyperbolic" model for strata movement under mining influence (Lei et al. 2023; Sun et al. 2021; Wei et al. 2020). Cheng and his colleagues applied the influence function method, considering the deformation mechanics and layered structure of strata, combined with the critical layer theory. They proposed the Influence Function Method-Key Stratum (IFM-KS) hybrid model, introducing final 2D subsidence prediction models, dynamic 2D subsidence prediction models, and final 3D subsidence prediction models, which have found extensive application in the field (Cheng et al. 2020a, b; Cheng et al. 2017; Cheng and Zhao et al., 2020b; Yang and Luo 2021).

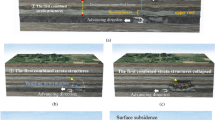

In single-seam mining, the movement of the overlying rock is transmitted to the surface, leading to hazards such as surface subsidence. As mining technology advanced and shallow coal reserves became depleted, the coal mining industry gradually transitioned towards deeper underground areas, inevitably encountering the challenge of secondary strata disturbance. Conversely, in multi-seam coal mining, strata movement impacts a larger area and causes more substantial damage through secondary strata movement(Erarslan 2016). This disrupts the integrity of the bottom plate in the upper airspace area, upsets the balance between the rock seams, and results in the breaking up of rock seams, creating serious fissures and leading to the leakage of hazardous gases into the airspace area at the working face. The key stratum (KS) is defined as a layer of thick and hard rock capable of bearing the weight of a part or all of the overlying strata, controlling the movement of a part or all of the strata. Research on the KS theory and the movement law of rock seams in multi-seam mining is of great engineering significance (Suchowerska et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2022). As shown in Fig. 1, varying thicknesses of the KS have different impacts on the collapse of the overlying rock, with different control scopes. The KS plays a key role in displacement control: a thicker KS provides stronger support to the overlying rock, leading to a smaller collapse range, whereas a thinner KS results in a larger collapse range.

The aforementioned research efforts have significantly contributed to the advancement of the theory for predicting overlying rock subsidence. However, there has been relatively less exploration into the movement of strata following multi-seam coal mining. In close-range mining, whether the seam spacing is greater or smaller than the height of the caving zone, it results in the further expansion of water-conducting fracture zones, an increase in development height, a decrease in the concentration factor of vertical stress in the overlying rock, and an intensification of deformation and failure (Guo et al. 2019; Mandal et al. 2008; Singh et al. 2008; Suchowerska Iwanec et al. 2016; Suchowerska et al. 2015; Wei et al. 2011). Ghabraie introduced various subsidence parameters, including the stacking relationship of different coal seams, and proposed a discrete influence function method to calculate the final subsidence displacement for each layer, which was then superimposed to obtain the overall final subsidence displacement (Ghabraie et al. 2015, 2017a, b). Jiang and his colleagues formulated a formula to calculate the subsidence coefficient under repeated mining conditions, validated through field measurements and comparisons. (Jiang et al. 2016). Zhu and Tu conducted research on the characteristics of rock breaking, coal seam spacing, and other aspects of multi-seam coal mining using methods like similar model tests and numerical simulations. Their study revealed that multi-seam coal mining leads to a significant increase in fissure zone height, and coal seam spacing had a substantial impact on subsidence. (Zhu and Tu 2017).

Xia et al. (2021) identified the communication of fissures as the primary cause of surface disturbance in multi-seam coal mining through numerical studies. When predicting the height of water-filled fracture zones and collapse zones under repeated mining, it is essential to consider seam height and seam spacing. Researchers proposed a three-step method for calculation: discrimination of coal seam group type, equivalent seam height calculation, and prediction of zone heights, validated through practical engineering applications (Li et al. 2022; Ning et al. 2020; Zhan et al. 2023). Sui discussed the impact of coal seam spacing and the thickness of the underlying coal seam on multi-seam mining. The results indicated that when the ratio (M, h/M) (where h represents the height of the inter-seam rock and M represents the height of the underlying coal seam) fell below a certain empirical guideline, repeated mining had a significant impact on subsidence and the development of water-conducting fracture zones. When this ratio fell above the guideline, the caving zone produced by the underlying coal seam mining did not connect with the upper goaf, which meant that the impact decreases with increasing seam spacing and decreasing thickness of the underlying coal seam (Sui et al. 2015). The majority of these studies primarily focused on numerical simulations, with relatively limited research on mathematical models for multi-seam coal mining. Porosity serves as quantitative measure of fracture the distribution within a mining area and is a pivotal parameter for describing gas migration behavior (Adhikary and Guo 2015; Hosking et al. 2020; Meng et al. 2016; Wood 2020). Wang through similarity model experiments and granular flow numerical simulations, quantitatively determined the height of the fracture zone, validating its effectiveness and reliability through field verification. Additionally, the study investigated the influence of stress ratio and main roof strength on the height of the fracture zone and permeability patterns (Wang et al. 2017).

In response to the multifaceted impacts stemming from multi-seam coal mining on strata movement, this study highlights the critical need to explore the nuanced influence of coal seam spacing on the characteristics of strata movement. This research aims to establish a comprehensive correlation between the complexities of multi-disturbed strata movement and the spacing of coal seams. By extending the Influence Function Method-Key Stratum (IFM-KS) hybrid model to include the intricacies of multi-seam coal mining scenarios, we develop a refined two-dimensional subsidence prediction model specifically tailored for conditions involving the re-mining of coal seams.

Moreover, this model reveals the intricate movement patterns of overlying strata that occur following multi-seam coal mining. Furthermore, it incorporates porosity calculations, enabling an insightful comparative analysis of porosity variations between single-seam and multi-seam coal mining. This comparative exploration delves into the interconnectivity of goaf areas and the formation of composite goaf regions.

The developed model significantly enhances the theoretical understanding of secondary disturbances in strata subsidence within scenarios involving the mining of coal seam groups or the extraction of closely situated coal seams. Beyond its theoretical contributions, the model holds substantial practical implications: it has the potential to improve coal mine safety, protect surface structures, and advance the field of strata movement research, ultimately supporting the development of more effective mining practices.

2 Strata movement model for single-seam coal mining

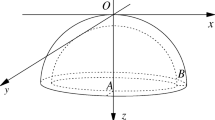

After coal seam extraction, the overlying rock movement invariably exhibited stratified characteristics (Do et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2012). Different underground rock layers experience varying loads and strengths. Therefore, the IFM-KS hybrid model takes into account the lithology of the rock layers and the influence of key strata. It calculates the subsidence displacements for different rock layers based on the division of natural rock strata. Subsequently, it calculates the vertical and horizontal displacements for each rock layer, resulting in the displacement curve of rock strata movement.

(Cheng and Wang et al. 2020a; Cheng et al. 2018).This method is suitable for continuous rock strata (Figs. 2, 3, 4 and 5).

The mathematical expression for the final subsidence displacement is given in Eq. (1).

where S(x, z) represents the final subsidence displacement. L represents the advance length of the working face. d signifies the offset distance of the turning point. m denotes the thickness of coal seam extraction.ai stands for the strata subsidence coefficient. Ri represents the main influencing radius. x’ represents the horizontal coordinate of the local coordinate system's prediction point. z represents the vertical coordinate of the prediction point in the global coordinate system.

The mathematical expression for the final horizontal displacement is as presented in Eq. (2). Consequently, the final horizontal displacement at the prediction point is a negative value.

where U(x, z) represents the final horizontal displacement.

3 Strata movement model for multi-seam coal mining

3.1 Establishing a model for rock strata movement in multi-seam coal mining

In the context of the single-layer coal mining model, the subsidence observed at the designated prediction position is a cumulative outcome of the excavations conducted beneath it. Consequently, in instances where there are two excavations situated below the prediction point, the subsidence is inherently influenced by the combined impact of these two excavation units. Following the extraction of the upper coal seam, the subsequent extraction of the lower coal seam induces subsidence in the intervening rock layers situated between the coal seams. The overlying rock of the upper coal seam is also disturbed, resulting in subsidence. The effect produced by the upper coal seam extraction is denoted as Sup. After the lower coal seam extraction, the prediction point between the coal seams is only influenced once by the lower coal seam extraction, and its subsidence is denoted as Sdown. However, for the overlying rock of the upper coal seam, it experiences two rounds of extraction influence, and the displacement at the prediction point is the accumulation of these two influences. Assuming the upper coal seam is not extracted, and only the lower coal seam is mined, the overlying rock of the upper coal seam produces a subsidence displacement of Sdown. After the upper coal seam extraction, the movement of the rock layers reaches a new equilibrium, forming a complex hinged structure. At this point, the subsidence displacement influenced by the lower coal seam extraction is no longer Sdown but is denoted as b*Sdown.

The subsidence observed following multi-seam coal mining is predominantly influenced by various factors, including the thickness of the lower coal seam extraction, the lithological characteristics of the rock layers, the morphological configuration of coal seam overlap, and the spacing between coal seams. While the single-layer coal model has traditionally accounted for considerations such as rock mechanical properties and mining thickness, the multi-seam coal model places heightened emphasis on assessing the impact of coal seam spacing. Here, b is an empirical coefficient related to coal seam spacing, and the subsidence of the overlying rock of the upper coal seam S2(x, zi) is given by Eq. (3):

where b represents the empirical coefficient. S2 stands for the subsidence displacement of the overlying rock of the upper coal seam, influenced by two mining disturbances.h1 is the burial depth of the upper coal seam.h2 is the burial depth of the lower coal seam.

With the boundary condition of h2 > > h1, S2 = Sup can be substituted into the above expression. Shifting Eq. (4) to the left, obtained:

In the coal mining process, it is commonly practiced to work from top to bottom, with the upper coal seam being initially extracted and the lower coal seam subsequently being extracted. Consequently, subsidence displacements resulting from these two extraction processes can only be observed. Hence, in Eq. (6), both S2 are unknown variables, representing the observed subsidence displacements following two rounds of extraction. On the other hand, Sup and Sdown are model-calculated values. By combining collected subsidence data from multiple real cases and similar simulated cases, a regression analysis is conducted to fit and establish an empirical formula for b, resulting in: \(b{ = }1.332e^{{\left( { - \left( {h_{2} - h_{1} } \right)/364.8} \right)}} + 0.015\)。

Hence, the establishment of the vertical strata movement model in multi-seam coal mining is as follows:

where h1 represents the burial depth of the upper coal seam, while h2 refers to the burial depth of the lower coal seam. S1 signifies the subsidence displacement of interlayer rock strata, influenced by a single mining disturbance.

Similarly, for the horizontal strata movement model in multi-seam coal mining:

where U1 represents the horizontal displacement of interlayer rock strata, influenced by a single mining disturbance. U2 signifies the horizontal displacement of the overlying rock of the upper coal seam, influenced by two mining disturbances.

3.2 Subsidence parameters of the model

In the rock strata movement models (Eqs. 3 and 4), three critical parameters, namely, ai, Ri, and di, are referred to as the final subsidence parameters. These parameters significantly impact the accuracy of the overall subsidence curve of the rock strata.

(1) Stratum subsidence coefficient ai.

The influencing factors of the stratum subsidence coefficient include depth, lithology, structure, and others, all of which notably affect surface and subsurface subsidence. A total of 148 subsidence coefficients were collected from cases of overlying rock movement, and through regression analysis, an empirical formula (Eq. 9) was derived.

(2) Offset distance of turning points di.

The critical juncture in the curve was identified as the turning point, signifying the transition from convex to concave. The offset distance of this turning point is defined as the horizontal distance from the inflection point to the edge. The empirical formula can be computed in accordance with the provided Equation (Cheng et al. 2017):

(3) Primary influence radius Ri.

The half of the horizontal distance Li from the edge of the rock strata movement basin to the nearest point of sufficient subsidence is defined as the primary influence radius Ri. To determine the influence radius of a specific rock layer, the rock layer can be idealized as a simply supported beam model that undergoes bending deformation. The left end is fixed at the edge of the subsidence basin, and the right end corresponds to the point with the nearest subsidence displacement of Smax(zi). By applying the formula for deflection of a simply supported beam in materials mechanics, an expression for the subsidence displacement of the rock strata can be derived (Eq. 11):

where Smax(zi) represents the subsidence displacement of the rock strata at its maximum, in meters (m). qi denotes the overlying load on the rock strata, measured in Newtons (N). Ei stands for the elastic modulus of the rock strata, in Newtons per meter (N/m). Ii represents the moment of inertia of the rock strata section, in meters to the fourth power (m4). Li is the horizontal length of the primary influence area, measured in meters (m).

According to the KS theory, the KS can bear the weight of a part of or all of the overlying strata and controls the movement of a part of or all of the strata. When the KS breaks, a part of or all of the strata above the KS would subside simultaneously (Wang et al. 2019). Therefore, the KS theory is introduced to help the load calculation and discernment of KS. This involves extending the IFM model to the IFM-KS hybrid model, combining both mechanical and geometric methods.

Considering the rock strata as a simply supported beam per unit width, the moment of inertia of the rock strata is \(I_{i} = \frac{1}{12}h^{3}\), rock strata's maximum subsidence displacement is \(S_{\max } (z_{i} ) = m \cdot a_{i}\), Combining the above equation, the expression for the primary influence radius Ri can be derived, as shown in Eq. (10)(Lu and Cheng 2018):

In the above equations, the key is to determine the load, qi, borne by the target rock layer. To achieve this, the critical layer theory needs to be introduced. Assuming there were m layers of rock strata with thickness hi and density ri above the coal seam roof, when the critical layer experienced movement, the overlying rock strata controlled by the critical layer will move synchronously, forming a structure similar to a composite beam( Xu et al. 2004). Taking the first layer of rock strata above the coal seam as an example, the formula for its superimposed load, qi, is calculated as shown in Eq. (11):

where\(q = \gamma_{1} h_{1} + \gamma_{2} h_{2} + \cdot \cdot \cdot + \gamma_{n} h_{n}\), \(I_{1} = \frac{{h_{1}^{3} }}{12}\;I_{2} = \frac{{h_{2}^{3} }}{12}\; \cdot \cdot \cdot \;I_{n} = \frac{{h_{n}^{3} }}{12}\), \((q_{n} )_{1}\) represents the load generated when considering the influence of n layers on the first layer. From this, it can obtain Eq. (12):

Equation (13) provides the formula for calculating the magnitude of the load on the first layer of rock strata. When calculating the overlying loads for each rock stratum in practice, Eq. (12) can also be used to determine the position of strata separation between soft and hard rock layers in the overlying rock strata. If the load from the nth layer on the first layer is greater than the load from the n + 1th layer on the first layer, it indicates the formation of a strata separation between the nth layer and the n + 1th layer. Since the n + 1th layer can bear a greater load, it was considered as the critical layer, ensuring that the loads from rock layers above the n + 1th layer do not continue to transmit to the rock layers below it(Qian et al. 1996).

4 Case study

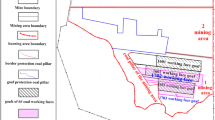

In this case study, attention is directed towards the 5106 working faces situated within the confines of Ekhovrak Coal Mine. The surface elevation of the working face spans from + 1868 to + 1934 m, encompassing a working face elevation range of + 1552 to + 1688 m. The coal seam burial depth fluctuates between 180 and 382 m, with an average burial depth stabilizing at 281 m. As delineated in Fig. 6, the discernible coal seams available for extraction are seam-1 and seam-5, positioned at a distance of 70 m from each other. The geological stratum identified as KS is situated above the roofs of these seams. The specific location of the KS is intricately tied to both the elastic modulus and mineral hardness. The KS's geometry exhibits superior hardness in comparison to other formations, as indicated by a higher modulus of elasticity and increased strength. The lithological characteristics of the KS are distinguished by a greater thickness in a singular stratum when contrasted with analogous rock formations. The KS plays a pivotal role in displacement control: a thicker KS provides robust support to the overlying rock, leading to a reduced collapse range; conversely, a thinner KS corresponds to an enlarged collapse range. This nuanced interplay underscores the critical influence of the KS in controlling displacement dynamics within the mining environment.

In Fig. 7, the layout delineates the southern segment as the unmined area of coal seam-5, the eastern part allocated for water barrier protection of coal pillars, and the northern section representing the 5104-goaf. Positioned above the 5106 working faces are the 1110-goaf and 1112-goaf. Coal seam-5, subject to mechanized coal mining within the 5106-working face, manifests a thickness ranging from 7.0 to 9.4 m, averaging 9 m. The topography of the 5106 working face area, situated in the southern foothills of the Tianshan fold belt at the northern margin of the Tarim block, exhibits a monocline structure in the foreland flexure zone. Characterized by low hills and ridges, semi-exposed bedrock, and surface coverage by Quaternary loess and gravel layers, the elevation of the caving zone extends to the surface throughout the mining process, inducing ground cracking and substantial surface subsidence. This phenomenon presents a potential hazard to both mine roads and natural gullies situated on the eastern side.

4.1 Setup of numerical model

Due to the extended monitoring intervals, instability, and inadequate reliability inherent in monitoring rock mass movement during practical production, the proposed model is validated using numerical simulation methods in this paper. The validity of the prediction model for strata movement in dual-seam coal mining is confirmed through the utilization of UDEC software and a specific case study as the research focus.

(1) Model and parameter settings.

The study is based on the 5106 working face of a particular mine. A model is established along the direction of the mine's working face, considering its geological data and the columnar structure of the coal seams. To simplify the model calculations and exclude the influence of working face support, rock layers with similar mechanical properties or smaller thicknesses are grouped, resulting in a total of 25 groups. The rock blocks are modeled using the Mohr–Coulomb model, and the joint model utilizes the Coulomb slip model with face contact. Table 1 lists the mechanical properties parameters used in the case (Fig. 8).

(2) Model boundary conditions.

The model created in UDEC 7.0 software has dimensions of 400 m in length, 280 m in height, and comprises a total of 25 coal and rock layers. The gravitational acceleration (g) is set to 9.8 m/s2. Horizontal displacement constraints are applied to the left and right boundaries of the model, meaning horizontal displacement is set to 0 at the x = 0 and x = 400 m boundaries. The bottom boundary (y = 0) represents vertical displacement, while the upper boundary is a free boundary.

(3) Simulated excavation plan.

During the coal mining process, a 50 m-wide area is left unmined on both the left and right sides of the model. The specific excavation steps are as follows:

-

(1)

Sequential excavation of the upper 1st coal layer, with each excavation being 50 m, and starting the next excavation after equilibrium calculation, resulting in a total excavation length of 300 m. Optimization of parameters is conducted to minimize discrepancies between simulated and calculated displacements.

-

(2)

Keeping the optimized parameters, the lower 5th coal layer is excavated in stages, with each excavation being 50 m. After each excavation, equilibrium calculations are performed before proceeding to the next excavation, resulting in a total excavation length of 300 m.

The displacement of rock layers above is monitored during the coal mining process, specifically the movements of groups 20, 21, 22, and 23, corresponding to monitoring lines A, B, C, and D, located 27 m, 34 m, 52 m, and 118 m above the upper coal layer, respectively. The displacement of rock layers is monitored, and the data is saved using the "history" command.

4.2 Calculation and comparative results of IFM-KS hybrid model

The subsidence contour maps for overlying rock in the upper and lower coal seam mining are shown in Figs. 9 and 10. In Fig. 9, it can be observed that the thickness of the upper coal seam mining is 4 m, with a maximum subsidence displacement of approximately 4 m. Notably, the mining influence is more pronounced within the first 100 m, resulting in a displacement of approximately 3.5 m in the overlying rock layers. The overall affected area exhibits a trapezoidal shape.

During the excavation of the lower coal seam, discernible subsidence phenomena manifest, characterized by significant displacement of rock layers situated between coal seams. These mining-induced effects extend to the overlying goaf, thereby accentuating the subsidence of rock layers above it and resulting in observable displacement. This influence extends to the surface, forming a trapezoidal-shaped affected area. During mining, when operations surpass widths of 50 m and 100 m (as seen in Fig. 10a and b), the impact on the overlying goaf gradually becomes less pronounced. The interlayer rock layers start to collapse at a width of 100 m. Deeper excavations at 150 m and 200 m (illustrated in Fig. 10c and d) witness significant subsidence in the interlayer rock layers, expanding the affected area with subsidence displacements ranging from 6 to 9 m. The influence on the overlying goaf area continues to grow, with localized subsidence reaching up to 9 m. As mining progresses to widths of 250 m and 300 m (as depicted in Fig. 10e and f), the affected area shifts in the direction of excavation. The increasing load on the overlying rock layers triggers their collapse, resulting in secondary subsidence. This leads to an expansion of the local subsidence area in the overlying goaf, denoted by the yellow dashed lines in Fig. 10d, e, and f, creating a peak-shaped affected area that steadily enlarges. The secondary subsidence typically lags behind the working face by approximately 100–150 m.

The mathematical model for multi-seam coal mining is implemented for expression calculations using MATLAB software, and the results are processed using Origin software. Subsidence comparison curves for survey lines A, B, C, and D after coal seam extraction are depicted in Figs. 11 and 12.

The comparative results demonstrate that the subsidence curves after coal seam mining exhibit good alignment and similar trends. Figure 11 reveals that after upper coal seam mining, significant errors exist on both sides of the goaf for all monitoring lines, approximately 1 m. This discrepancy is due to the fact that the numerical model does not entirely account for the collapse of the cantilever beams on both sides. The consideration of the main influence radius (Ri) and subsidence coefficient (ai) in the calculations indicates that the closer the distance between the rock layers and coal seams, the greater the degree of collapse. The overall subsidence error for lines C and D is relatively small, with subsidence curves closely matching. However, due to the division of rock layers and the stepwise advance of the working face in UDEC, these lines exhibit some fluctuations in subsidence displacements. Notably, the simulated subsidence displacements at 60 m and 80 m are greater than the IFM-KS hybrid model's calculated values, while between 200 and 300 m, they are lower.

From Fig. 12, it is evident that after lower coal seam mining, the subsidence curves simulated by UDEC show similar trends to those from the model calculations. However, the subsidence displacements on both sides are lower than the model-calculated values, while they are higher in the middle. Lines A, B, and C exhibit minimal displacement errors and good alignment with the model subsidence curves. In contrast, line D demonstrates a larger error due to the fact that in the UDEC simulation, significant subsidence occurs in the overlying rock layers when the key layer fractures. In the moving model, the calculation of rock layer subsidence fully considers the role of key layers, particularly the interlayer key layers in the subsidence of the overlying rock layers. Additionally, the assumption that the upper coal seam is not mined leads to differences in the loads on the rock layers from the actual loads. In this case, the key layers do not fracture, and the more key layers between the prediction point and the working face, the smaller the calculated results.

From Table 2, it can be observed that there are certain errors in the measurements at various points.

Along monitoring lines A, B, C, and D following multi-seam coal mining, the average error for monitoring line A is 1.07 m, with an average error rate of 23%. The maximum error recorded is 3.19 m at a specific point. Monitoring line B exhibits an average error of 0.85 m, with an average error rate of 18%. The maximum error recorded is 2.56 m, due to its proximity to one side. Similarly, for monitoring line C, the average error is 0.78 m, with an average error rate of 17%. The maximum error recorded is 1.98 m at a specific point. Monitoring line D shows a similar trend in settlement curves. Due to the consideration of the key layer's impact in the computational model, the errors are relatively high, with an average error of 1.31 m and an average error rate of 24%. The maximum error recorded is 3.05 m. Owing to the value of settlement is small and the basic figure is small, the error rate appears to be large.

In the horizontal direction, the errors are concentrated mainly on the left and right sides because the model takes into account the influence radius and the effect of the cantilever beams on both sides. Within a 40 m range on either side, the errors are relatively high, which is more than three times the error in the middle. In the longitudinal direction, as the distance from the excavated coal layer increases, the model's calculated settlement values become smaller relative to the simulated values, resulting in larger errors. This is because monitoring line D is situated at the roof of the subkey layer, and the model considers the influence of the key layer, leading to smaller calculated settlement values. Overall, the multi-seam coal mining model's errors fall within an acceptable range, demonstrating a certain level of applicability.

4.3 Porosity of overlying strata due to repeated coal mining

Post-coal mining, the fractured void spaces within the overlying strata, formed as a consequence of strata collapse, serve as the principal zones for air leakage and gas flow in the goaf. The dynamics of gas flow in the goaf are predominantly influenced by the factors of porosity and permeability. The porosity distribution is a critical parameter for describing gas migration, as well as a key indicator for characterizing the fractures in the goaf. When establishing the relationship between coal and rock porosity and the total strain, it is essential to consider the structural deformation of coal and rock bodies while ignoring their small intrinsic deformation and lateral displacement. This analysis and derivation are conducted in conjunction with the rock strata movement model.

In accordance with the definition of porosity, the initial porosity of the coal and rock mass in its undeformed state is given by:

Where ϕ0 represents the initial porosity. Vp denotes the volume of void spaces within the porous medium. Vt is the total volume of the coal and rock mass.

When subjected to the influence of mining activities, the new porosity of the coal and rock mass at a particular state can be expressed as follows:

where ϕ represents the porosity of the coal and rock mass, and εt denotes the volumetric strain.

The strain εt can be expressed as:

Therefore, taking the working face orientation as an example, for the cross-section at the center of the working face with a mining length of 300 m, the porosity distribution of the overlying strata under the influence of mining is calculated, as shown in Figs. 13 and 14.

After upper coal mining, the cross-sectional porosity distribution cloud map reveals that the coal mining area has the highest porosity, with values exceeding 0.156 on both sides. In the middle of the goaf area, the porosity is greater than 0.138, indicating the presence of numerous fractures in this region. On either side of the key layer location, the maximum porosity is 0.156, and in the middle, it's about 0.109. This suggests that the key layer may not have undergone fracturing, but there are areas above it where porosity has increased. In the sub-key layer region, the porosity is relatively low, and the rock layers have moved as a whole, with no clearly defined large fracture areas. However, above these layers, there are regions with higher porosity, and both rock layers are relatively thick. This indicates a phenomenon of separation between the rock layers. After upper coal mining, the key layer plays a significant role, and within 20 m, there is relatively higher porosity. There are localized areas with increased porosity above the two key layers, suggesting the possibility of separation between layers. However, the rock layers remain relatively intact with an overall lower average porosity.

After lower coal mining, the porosity distribution cloud map in the longitudinal cross-section reveals significant damage to the rock layers between the coal seams. A collapsed zone has formed between the inter-layer key layer and the lower coal seam, with a porosity of approximately 0.19. At a distance of 40 m from the working face, where the inter-layer key layer is located, the porosity on both sides is around 0.23, indicating the presence of a fracture zone extending to the upper goaf area. Between the inter-layer key layer and the upper coal seam, the rock layers are supported by the key layer and have not undergone fragmentation, resulting in lower porosity, around 0.12.

Compared to upper coal mining, multi-seam coal mining has increased the porosity. The two mining operations have caused significant rock fragmentation in the overlying strata, resulting in an average porosity of about 0.15. At a distance of 80 m from the working face, the porosity on both sides is 0.23, while in the middle, it is 0.175. Due to the action of cantilever beams, the rock layers on both sides have collapsed and become stacked, leading to larger porosity. At a distance of 130 m from the working face, there is significant porosity, indicating the possibility of layer separation. As the distance from the working face increases, the affected area gradually decreases, and the regions with higher porosity form a "trapezoidal shape."

According to the porosity distribution map, there is higher porosity on both sides between the upper and lower goaf areas. This suggests the presence of significant fractures between the lower coal seam working face, the upper goaf area, and the surface, creating air passage pathways, ultimately resulting in surface air leakage.

5 Conclusions

Given that the IFM-KS hybrid model is designed for single coal mining applications using a "mechanical model-geometric method" approach, this paper introduces a rock strata movement model suitable for multi-seam coal mining and substantiates its applicability through a specific case of dual coal layer extraction. This model provides valuable insights for forecasting rock layer settlements in multi-coal layer mining scenarios, leading to the following noteworthy conclusions:

-

(1)

In this study, a rock strata movement model suitable for multi-seam coal mining conditions is constructed in this study. The relationship between rock strata movement and the distance from coal seams is established. The model applicable to multi-seam coal mining is derived, revealing the deformation patterns of rock strata after the secondary disturbance due to repetitive coal mining. The rock strata movement at the 5106 working face is analyzed through the model incorporating the movement of dual-layer coal rock strata. The UDEC software is used to model dual-layer coal mining scenarios. Comparative analyses of the displacement curves of rock strata following two rounds of mining are conducted. Notably, the displacement curve for the upper coal layer exhibits minimal errors and displays a high level of congruence. Following the mining of the lower coal layer, the subsidence displacements of the rock strata at designated positions along lines A, B, and C exhibit minimal disparities in comparison to the subsidence model calculations. The subsidence curves exhibit a commendable level of consistency and exhibit similar trends, affirming the practical applicability of the multi-seam coal mining rock strata movement model.

-

(2)

The study conducts an in-depth analysis of porosity distribution following multi-seam coal mining in 5106 working faces. Compared to single-layer coal mining, a significant change in porosity is observed. Multi-seam coal mining results in more severe damage to overlying rock strata, increasing the possibility of establishing connections within the goaf area and thus creating air passages. With increasing distance from the working face height, the affected area gradually reduced in size, and regions with higher porosity. According to the porosity distribution map, there are fissure pathways on both sides between the upper and lower goaf areas. These pathways may be linked to larger fissure channels that facilitate the connection between the surface and the upper goaf area, ultimately resulting in air leakage to the surface.

Data availability

Conflict of Interest Statement The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper. Data Availability Statement The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Jianwei Cheng, upon reasonable request. Funding Statement This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. All resources utilized for this study were provided by the authors' institutions and personal contributions.

Change history

12 October 2025

The original online version of this article was revised: The Acknowledgements section was mentioned as None in the article and it has been updated.

24 October 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-025-01056-9

References

Adhikary DP, Guo H (2015) Modelling of longwall mining-induced strata permeability change. Rock Mech Rock Eng 48(1):345–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-014-0551-7

Barbato J, Hebblewhite B, Mitra R, Mills K (2016) Prediction of horizontal movement and strain at the surface due to longwall coal mining. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 84:105–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2016.02.006

Cheng J, Liu F, Li S (2017) Model for the prediction of subsurface strata movement due to underground mining. J Geophys Eng 14(6):1608–1623. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-2140/aa8238

Cheng J, Zhao G, Li S (2018) Predicting underground strata movements model with considering key strata effects. Geotech Geol Eng 36(1):621–640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-017-0307-8

Cheng J, Wang Z, Li S, Song W, Lu W, Zhang Y, Zhao K (2020a) Subsurface strata failure and movement based for improving gas emission control: model development and application. Energy Sci Eng 8(9):3285–3302. https://doi.org/10.1002/ese3.723

Cheng J, Zhao G, Feng G, Li S (2020b) Characterizing strata deformation over coal pillar system in longwall panels by using subsurface subsidence prediction model. Eur J Environ Civ Eng 24(5):650–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/19648189.2017.1415981

Cyrul T (1993) Prediction of rock and gas outburst occurrence. Eng Geol 33(3):241–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-7952(93)90061-G

Deck O, Baroudi H, Hosni A, Gueniffey Y (2018) A time dependency prediction of the number of mining subsidence events over a large mining field with uncertainties considerations. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 105:62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2018.03.010

Do NA, Dias D, Dinh VD, Tran TT, Dao VC, Dao VD, Nguyen PN (2019) Behavior of noncircular tunnels excavated in stratified rock masses—Case of underground coal mines. J Rock Mechan Geotechn Eng 11(1):99–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2018.05

Erarslan N (2016) Microstructural investigation of subcritical crack propagation and Fracture Process Zone (FPZ) by the reduction of rock fracture toughness under cyclic loading. Eng Geol 208:181–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2016.04.035

Ewy RT, Hood M (1984) Surface strain over longwall coal mines: its relation to the subsidence trough curvature and to surface topography. Int J Rock Mechan Mining Sci Geomechan Abstracts 21(3):155–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-9062(84)91533-X

Gentry DW, Abel JF Jr (1978) Surface response to longwall coal mining in mountainous terrain. Environ Eng Geosci. https://doi.org/10.2113/gseegeosci.xv.2.191

Ghabraie B, Ren G, Zhang X, Smith J (2015) Physical modelling of subsidence from sequential extraction of partially overlapping longwall panels and study of substrata movement characteristics. Int J Coal Geol 140:71–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2015.01.004

Ghabraie B, Ren G, Barbato J, Smith JV (2017a) A predictive methodology for multi-seam mining induced subsidence. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 93:280–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2017.02.003

Ghabraie B, Ren G, Smith JV (2017b) Characterising the multi-seam subsidence due to varying mining configuration, insights from physical modelling. Int J Rock Mechan Mining Sci 93:269–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2017.02.001

Guo W, Zhao G, Lou G, Wang S (2019) A new method of predicting the height of the fractured water-conducting zone due to high-intensity longwall coal mining in China. Rock Mech Rock Eng 52(8):2789–2802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-018-1567-1

Holla L (1997) Ground movement due to longwall mining in high relief areas in New South Wales, Australia. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 34(5):775–787. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1365-1609(97)00004-1

Hosking LJ, Chen M, Thomas HR (2020) Numerical analysis of dual porosity coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical behaviour during CO2 sequestration in coal. Int J Rock Mechan Mining Sci 135:104473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2020.104473

Jiang B, Wang L, Lu Y, Sun X, Jin G (2016) Ground pressure and overlying strata structure for a repeated mining face of residual coal after room and pillar mining. Int J Min Sci Technol 26(4):645–652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2016.05.017

Kumar R, Singh AK, Mishra AK, Singh R (2015) Underground mining of thick coal seams. Int J Min Sci Technol 25(6):885–896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2015.09.003

Lei B, Zuo J, Massimo C, Wu G, Liu H, Yu X (2023) Experimental and numerical investigation on meso-fracture behavior of Beishan granite subjected to grain size heterogeneity. Eng Fract Mech 292:109623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2023.109623

Levinson Z, Dimitrakopoulos R (2023) Connecting planning horizons in mining complexes with reinforcement learning and stochastic programming. Resour Policy 86:104136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.104136

Li P, Peng D, Tan Z, Deng K (2017) Study of probability integration method parameter inversion by the genetic algorithm. Int J Min Sci Technol 27(6):1073–1079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2017.06.006

Li Q, Wu G, Kong D, Han S, Ma Z (2022) Study on mechanism of end face roof leaks based on stope roof structure movement under repeated mining. Eng Fail Anal 135:106162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106162

Liu T (1995) Mining rock mass mining impact and control engineering and its application. J China Coal Soc 01:1–5

Lu W, Cheng J (2018) Research on permeability changes of overlying rock mass in working face based on rock movement calculation. J Mining Safety Eng 35(01):118–124. https://doi.org/10.13545/j.cnki.jmse.2018.01.017

Mandal PK, Singh R, Maiti J, Singh AK, Kumar R, Sinha A (2008) Underpinning-based simultaneous extraction of contiguous sections of a thick coal seam under weak and laminated parting. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 45(1):11–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2007.03.005

Meng Z, Shi X, Li G (2016) Deformation, failure and permeability of coal-bearing strata during longwall mining. Eng Geol 208:69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2016.04.029

Moon V, Roy T (2004) Geological controls on rock mass classification of coal from Huntly East Mine. N Zeal Eng Geol 75(2):201–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2004.05.007

Ning J, Wang J, Tan Y, Xu Q (2020) Mechanical mechanism of overlying strata breaking and development of fractured zone during close-distance coal seam group mining. Int J Min Sci Technol 30(2):207–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2019.03.001

Poggi G, Dallai L, Volpi V (2023) Mining under the canopy: Unveiling the archaeo-mining record in the Colline Metallifere with LiDAR analysis and multidisciplinary studies. Quaternary Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2023.08.006

Qian M, Miao X, Xu J (1996) Research on key layer theory in stratum control. J China Coal Soc 03:2–7

Singh R, Sheorey PR, Singh DP (2002) Stability of the parting between coal pillar workings in level contiguous seams. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 39(1):9–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1365-1609(01)00080-6

Singh R, Mandal PK, Singh AK, Kumar R, Maiti J, Ghosh AK (2008) Upshot of strata movement during underground mining of a thick coal seam below hilly terrain. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 45(1):29–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2007.03.006

Suchowerska AM, Merifield RS, Carter JP (2013) Vertical stress changes in multi-seam mining under supercritical longwall panels. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 61:306–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2013.02.009

Suchowerska AM, Carter JP, Hambleton JP (2015) Geomechanics of subsidence above single and multi-seam coal mining. J Rock Mechan Geotechn Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2015.11.007

Suchowerska Iwanec AM, Carter JP, Hambleton JP (2016) Geomechanics of subsidence above single and multi-seam coal mining. J Rock Mechan Geotechn Eng 8(3):304–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2015.11.007

Sui W, Hang Y, Ma L, Wu Z, Zhou Y, Long G, Wei L (2015) Interactions of overburden failure zones due to multiple-seam mining using longwall caving. Bull Eng Geol Env 74(3):1019–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-014-0674-9

Sun Y, Zuo J, Karakus M, Wen J (2020) A novel method for predicting movement and damage of overburden caused by shallow coal mining. Rock Mech Rock Eng 53(4):1545–1563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-019-01988-1

Sun Y, Zuo J, Karakus M, Liu L, Zhou H, Yu M (2021) A new theoretical method to predict strata movement and surface subsidence due to inclined coal seam mining. Rock Mech Rock Eng 54(6):2723–2740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-021-02424-z

Sun K, Zhang J, He M, Li M, Guo S (2023) Control of surface deformation and overburden movement in coal mine area by an innovative roadway cemented paste backfilling method using mining waste. Sci Total Environ 891:164693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164693

Wang G, Wu M, Wang R, Xu H, Song X (2017) Height of the mining-induced fractured zone above a coal face. Eng Geol 216:140–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2016.11.024

Wang F, Xu J, Xie J (2019) Effects of arch structure in unconsolidated layers on fracture and failure of overlying strata. Int J Rock Mechan Mining Sci 114:141–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2018.12.016

Wei X, Bai H, Rong H, Jiao Y, Zhang B (2011) Research on mining fracture of overburden in close distance multi-seam. Procedia Earth Planetary Sci 2:20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeps.2011.09.004

Wei X, Zuo J, Shi Y, Liu H, Jiang Y, Liu C (2020) Experimental verification of parameter m in Hoek-Brown failure criterion considering the effects of natural fractures. J Rock Mechan Geotechn Eng 12(5):1036–1045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2020.01.006

Wood DA (2020) Predicting porosity, permeability and water saturation applying an optimized nearest-neighbour, machine-learning and data-mining network of well-log data. J Petrol Sci Eng 184:106587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2019.106587

Wu L, Qian M, Wang J (1997) The influence of a thick hard rock stratum on underground mining subsidence. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 34(2):341–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-9062(96)00028-9

Xia Z, Yao Q, Meng G, Xu Q, Tang C, Zhu L, Wang W, Shen Q (2021) Numerical study of stability of mining roadways with 6.0-m section coal pillars under influence of repeated mining. Int J Rock Mechan Mining Scinces 138:104641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2021.104641

Xu J, Qian M, Jin H (2004) Study on the evolution law of stratum movement and separation and its application. Chin J Geotechn Eng 05:632–636

Yang J, Luo Y (2021) Enhanced subsurface subsidence prediction model incorporating key strata theory. Mining Metall Explorat 38(2):995–1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42461-021-00383-1

Zhan H, Liu S, Wu Q, Li Y, Qi K, Zhang X (2023) Quantitative prediction of the impact of deep extremely thick coal seam mining on groundwater. Process Safety Environ Protect 178:511–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2023.08.061

Zhang ZX, Xu Y, Kulatilake PHSW, Huang X (2012) Physical model test and numerical analysis on the behavior of stratified rock masses during underground excavation. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 49:134–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2011.11.001

Zhang Z, Mei G, Xu N (2022) A geometrically and locally adaptive remeshing method for finite difference modeling of mining-induced surface subsidence. J Rock Mechan Geotechn Eng 14(1):219–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2021.11.001

Zhang J, He M, Yang G, Wang Y, Hou S (2023) N00 Method with double-sided roof cutting for protecting roadways and surface strata. Rock Mech Rock Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-023-03657-w

Zhu D, Tu S (2017) Mechanisms of support failure induced by repeated mining under gobs created by two-seam room mining and prevention measures. Eng Fail Anal 82:161–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2017.08.029

Acknowledgements

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the late Dr. Yi Luo for his groundbreaking contributions and visionary guidance that laid the foundation for this research. His profound insights into the dynamics of strata deformation, particularly through the development of the Influence Function Method (IFM) model, have been instrumental in shaping the development of Influence Function Method- Key Stratum hybrid model in this study. Dr. Luo’s emphasis on understanding multi-seam mining-induced strata deformation and porosity dynamics continues to inspire advancements in this field, even after his passing in 2022. This research stands as a testament to his enduring contributions to mining engineering and geomechanics.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities 2020CXNL02; The project is sponsored by the Xinjiang Key Research and Development Special Task (Grant No. 2022B03003-3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Contributions Statement Jianwei Cheng conceptualized and designed the study, and contributed to the development of the hybrid model. Shuping Sheng and Yonggang Xu assisted with the model development and performed the validation against field data. Yi Luo provided insights into the application of the influence function method, while Md Mojahidul Islam contributed significantly to data analysis, the interpretation of results, and the preparation of supplementary materials. Jianwei Cheng wrote the main manuscript text, with assistance from Shuping Sheng, and Shuping Sheng and Yonggang Xu prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: The Acknowledgements section was mentioned as None in the article and it has been updated.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, J., Sheng, S., Xu, Y. et al. Deformation prediction of overlying strata in multi-seam mining based on the influence function method-key stratum hybrid model. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-energ. Geo-resour. 10, 178 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-024-00875-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-024-00875-6