Abstract

Incidents of child-to-parent aggression have been the most under-researched area of domestic violence. The risk factors for child-to-parent aggression are still unknown. This article reviews risk factors that might explain aggression among adolescents. First, an overview of aggression, with a primary focus on child-to-parent aggression is provided. A number of studies on young people’s aggression show callous-unemotional traits as a predictor of aggression toward peers. However, callous-unemotional traits have not been studied in research on parent-directed aggression, even though they have been shown to be related to social dominance and lack of care toward authority figures (of which parents have a key role during adolescence). Thus, a new “Trait-Based Model” is proposed to explain child-to-parent aggression. In the model, the perpetrators of child-to-parent aggression are divided into two types: “generalists”, who are high on callous-unemotional traits and are proposed to perpetrate aggression toward parents as well as toward others outside the family, and “specialists”, who are low on callous-unemotional traits and specifically perpetrate aggression toward parents but not in other contexts. This article argues for future research to investigate the role of personality traits typically predicting differing subtypes of aggression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Child-to-parent aggression or parent-directed aggression was defined as “any act of a child or adolescent that is intended to cause physical, psychological, or financial damage to gain power and control over a parent” (Cottrell 2001, p. 3; Kennair and Mellor 2007, p. 204; Calvete et al. 2013). Although originally identified over 30 years ago (Harbin and Maddin 1979), child-to-parent aggression is a social problem that has remained predominantly hidden (Contreras and Cano 2014). The victims of child-to-parent aggression are less likely to report the incidents. Mainly, parents may feel embarrassed and confused when they become the victim of child aggression (Kennair and Mellor 2007). Some parents fear the child’s reaction (Perez and Pereira 2006), may feel responsible for their child’s aggressive behavior (Margolin and Baucom 2014), or may want to protect the family image (Perez and Pereira 2006). All of these factors might lead them to conceal the violence (Margolin and Baucom 2014). In some cases, parents may normalize their child’s aggressive behavior (Gallagher 2008). Consequently, the issues only remain known within the immediate family (Martínez et al. 2015). This explains why little is known regarding the current prevalence issue.

Despite these barriers to parents’ reporting child-to-parent aggression and the lack of research into it, however, it may be a fairly common phenomenon. For instance, research in the US, Canada, and Spain reported prevalence values of between 4.6 and 21% for physical aggression toward parents (Calvete et al. 2013; Ibabe and Jaureguizar 2010; Nock and Kazdin 2002). Some large-scale studies on community samples estimated that 9–14% of parents would, at some point, be physically assaulted by their adolescent children (Cottrell and Monk 2004), while data from Canadian, Australian, and British studies suggests 1 out of 10 parents are assaulted by their children (Howard 2011). Moreover, recent reviews have highlighted an increasing rate at which child-to-parent aggression is reported (Coogan 2011). Thus, the issue can no longer be ignored, as there appears to have been a lack of awareness of children engaging in domestic violence toward their parents (Dahlitz 2015). Findings from past studies indicate that the most common victims of young people’s aggression at home are siblings (Eriksen and Jensen 2006; Purcell et al. 2014). However, parents may be the “hidden” victims of domestic violence perpetrated by children (Kennair and Mellor 2007). Hunter and Nixon (2012) also described a “veil of silence” surrounding this topic of parent-directed aggression in domestic violence. This may be one reason why child-to-parent aggression remains the most under-researched form of family aggression (Hong et al. 2012; Walsh and Krienert 2007). Thus, neglecting research on child-to-parent aggression ignores a significant aspect of domestic violence (Kennedy et al. 2010). Because of the limited number of studies conducted in this area, little is known about the personality of adolescents who perpetrate aggression toward their parents. Therefore, the present review has been undertaken with the primary goal of exploring the possible mechanisms driving child-to-parent aggression. Studying this area will aid with understanding which young people are most likely to perpetrate this type of family aggression, but may also provide critical information about how to identify this emerging problem.

The Current Review

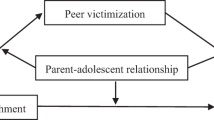

In this section, the aims of this review are presented and a newly developed model will be briefly discussed. Firstly, the prevalence of family aggression and the profile of young perpetrators are examined. Secondly, the risks and protective factors parenting presents to childhood aggression is discussed. Thirdly, understanding the role of emerging callous-unemotional traits in young people is argued to be a major factor that is missing from prior family aggression research. Fourthly, a possible mechanism behind a putative link between callous-unemotional traits and aggression in the family—specifically the goals behind the use of aggression is hypothesized. Finally, a new “Trait-Based Model” is proposed to explain two types of young perpetrators in parent-directed aggression as shown in Fig. 1. The first type are “generalists” who are argued to perpetrate aggression toward parents and also toward non-family members. The second type are “specialists” who are proposed to solely perpetrate aggression toward their parents but not toward other people. That is, elevated callous-unemotional traits might designate young people who are “generalists”, seeking physical (and psychological) dominance both in and outside the home. In contrast, young people who are low on callous-unemotional traits might specialize in aggression to their parents as a reaction toward harsh parenting.

The Prevalence of Child-to-Parent Aggression Based on the Profile of Perpetrators

This section will examine the prevalence of family aggression based on the profile of young perpetrators, which includes their age, family structure, and gender. Most research in this area has found that adolescents begin perpetrating child-to-parent aggression between the ages of 14–17 years (Kethineni 2004; Snyder and McCurley 2008; Walsh and Krienert 2007). Of late, young perpetrators of 16 and 17 years of age may be held accountable for domestic violence in the UK (Gov. UK Home Office 2016). However, in the UK, child-to-parent aggression, in particular, is not considered domestic violence if the perpetrator is under 16 years of age (Condry and Miles 2014). If parents choose to report being abused by their child, the police can only advise the child not to do it again. Interestingly, parents could be treated as “adult at risk” and supported by professionals in this framework, particularly if they themselves had a particular condition, such as a mental health problem or learning disability (Office of the Public Guardian 2015). Despite not appearing in either UK criminological, youth justice or policy, in the past 2 years, there have been 1892 cases of child-to-parent aggression reported to social services in London and perpetrators were between 13 and 19 years of age (Condry and Miles 2014). This suggests that young people might have been aggressive toward their parents to the extent that parents felt the need to report the incidents to someone beyond the immediate family. While some parents reported aggression that started since the child was as young as 5 years of age, other parents reported sudden abusive behavior that started during adolescence (i.e., around 12 years old) (Holt 2016). Moffitt (1993) classified young people’s aggression into two trajectories. The first path emerges during adolescence and decreases over time. The second path begins earlier in life and persists into adulthood. To date, there are still limited studies that have examined parent-directed aggression from a developmental perspective (Holt 2016). The article aims to fill this knowledge gap by introducing a new framework to help explain the different circumstances where these incidents of child-to-parent aggression occur, touching on some developmental perspectives.

Besides age-related factors, family structure and socioeconomic status also seem to contribute to the likelihood of child-to-parent aggression. Although child-to-parent aggression can occur regardless of family structure, Romero et al. (as cited in Martínez et al. 2015) found more cases of child-to-parent aggression among extended families and stepfamilies when compared to intact families. Nock and Kazdin (2002) found aggression to be prevalent among two-parent families, while more studies have emphasized the risk of single-parent families to child-to-parent aggression (Gallagher 2009; Ibabe et al. 2009; Kennedy et al. 2010; Routt and Anderson 2011; Walsh and Krienert 2009). With regard to socioeconomic status, child-to-parent aggression has been found to be more likely in both middle and upper socio-economic brackets versus others (Charles 1986; Paulson et al. 1990). Contrastingly, Routt and Anderson (2011) found it to be more prevalent among low income families compared to those from high income families. Evidence-based health visitor intervention programs have been conducted in several countries, including the USA, Australia, New Zealand (Olds et al. 2007) and the UK (Barlow et al. 2007), focusing on the potential risk of low economic status by targeting vulnerable families (i.e., unmarried mothers and low socioeconomic background). During these programs, health visitors visited the mothers at prenatal periods and early childhood, with the aim to improve prenatal behaviors and environmental conditions early in the life cycle to prevent maternal and child health problems (Olds 2002). These home-visit interventions appeared to be an effective approach in significantly reducing psychological aggression on children (Landsverk et al. 2002). Thus, improving parental behavior and families’ economic conditions may reduce the risk of children developing early-onset behavior problems (Olds et al. 1998; Olds 2002). Since those children with early-onset antisocial behavior tend to commit more offences over a longer time period than late-onset (Farrington et al. 2006), preventing early-onset offending could also prevent child-to-parent aggression by targeting shared risk factors.

Most studies indicate boys as more likely to assault their parents (Boxer et al. 2009; Gallagher 2008; Kennedy et al. 2010; Routt and Anderson 2011; Walsh and Krienert 2007). In those studies, the percentage of males among adolescent perpetrators was between 60 and 80%. A study in Canada, which included a community sample of 3000 adolescents (15–16 years of age) showed that 12.3% of boys and 9.5% of girls had perpetrated aggression toward their father within the past 6 months (Pagani et al. 2009), i.e., only 56% of perpetrators in the community sample were male. The higher prevalence of males in the forensic sample in particular may arise due to the overrepresentation of males who are adjudicated. This may also imply that sons tend to be reported by parents more than daughters are (Gallagher 2008), which makes sense given that post-puberty, boys can cause more physical harm. Notably, several studies have found no difference in the prevalence rate of parent-directed aggression between boys and girls (Cottrell 2001; Pagani et al. 2004; Paterson et al. 2002), reflecting the literature on intimate partner violence between men and women. As in the intimate partner violence literature, differences between boys and girls depend on the type of aggression—boys are more likely to perpetrate physical aggression and girls are more likely to perpetrate psychological aggression (Ibabe and Jaureguizar 2011) and verbal aggression (Calvete et al. 2013). In addition, a Western Sydney study found that 51% of sole mothers experienced abuse and violence from their adolescent, with the most common cohort being male adolescent violence against mothers (Stewart et al. 2007).

Although family conflict may increase during adolescence, generating more conflicts between family members (Contreras and Cano 2014), it is important to note that there is a clear boundary between parent abuse and problematic behaviors that could be regarded as part of “normal” adolescent behavior (Coogan 2011). Martínez et al. (2015) stated that what differentiates child-to-parent aggression from adolescents’ “normal” rebellious behavior is an “exercise of power”. Some adolescents may choose to resist being led by their parents. Those who strive to release themselves from such parental control may choose to dominate, coerce, and control their parents by using aggression (Tew and Nixon 2010). Unsurprisingly perhaps, delinquent samples have been found to be more aggressive than community samples in general. They were also more physically aggressive and may be the ones to perpetrate the most violence in the home as compared to community samples (Kuay et al. 2016). Earlier studies highlighted that young people who perpetrated aggression at home are different from the perpetrators of juvenile crimes and domestic violence (Brezina 1999; Walsh and Krienert 2007). Kennedy et al. (2010) emphasized the importance of differentiating adolescents who perpetrate aggression at home from their peers who only commit aggression outside the home. However, those who perpetrate aggression in and outside the home environmental context may also need different intervention. So, in the “Trait-Based Model” (Fig. 1), it is suggested that adolescents who are high on callous-unemotional traits are more likely to be “generalists” in their use of aggression—less context dependent. They are more antisocial than their peers who are low on these traits, most aggressive toward parents, and most aggressive toward peers. In the next section, the potential role of parenting styles in predicting aggression in “generalists” versus “specialists” are considered.

Parenting Practices and Child-to-Parent Aggression: Fitting Parenting Styles into a Model

The profile of perpetrators may contribute to their attitude that perpetrating aggression toward their parents is acceptable. However, adolescents are not only influenced by their own characteristics and life experiences; their aggressive behavior may also originate from their parents—transmitted through childrearing practices. Parents may use different techniques to interact with their child and build a relationship with them. One of the most influential theories on parenting styles was introduced by Baumrind (1967). She identified three preliminary parenting styles which are authoritative parenting, authoritarian parenting, and permissive parenting. Maccoby and Martin (1983) then expanded the theory by placing the parenting styles into a two-dimensional model as: (1) demanding and responsive (authoritative); (2) demanding and unresponsive (authoritarian); (3) undemanding and responsive (permissive); and additionally: (4) undemanding and unresponsive (neglectful). Authoritative parenting was viewed as promoting child maturity, confidence, and independence (Herbert 2004). Authoritarian parents raised children who were highly obedient, unhappy, and rebellious when they enter adolescence; and some suffered from depression (Maccoby and Martin 1983). Permissive parenting raised children who were immature, irresponsible, and may engage in delinquent behavior (Calvete et al. 2014). Finally, children who grow up with neglectful parents tend to be undisciplined, emotionally withdrawn from social situations, and more likely to portray patterns of truancy and delinquency (Bornstein 2002).

Past studies show adolescents who experienced harsh discipline, poor attachment with parents, or lack of parental supervision have problematic behaviors (Hoeve et al. 2012; Marcus and Betzer 1996; Vazsonyi and Flannery 1997). Many adolescents never learn how to handle frustration and may not be able to feel emotions other than anger and hopelessness (i.e., exhibit poor emotional regulation and emotional literacy). Prior research also found hostile parenting was related to the child’s physical aggression (Benzies and Mychasiuk 2009). Straus et al. (1980) theorized that parents who used harsh parenting techniques (i.e., were themselves modelling hostile and aggressive interactions) were at a higher risk of being assaulted by their child in the future compared to those who used non-aggressive techniques. A similar finding was noted two decades later by Ulman and Straus (2003) in their study on child-to-parent aggression. Exposure to violence at home either as a witness or victim of domestic violence can be detrimental to young people, putting them at an inflated risk for using aggression themselves (Routt and Anderson 2011). Patterson (1980) also highlighted that it is not parental punishment that leads to child-to-parent aggression, but it is the inconsistency in punishment that predicts child-to-parent aggression. From those studies, it is evident that parents who practiced harsh parenting or inconsistent punishment increased the chance of their child perpetrating aggression toward them. However, this may only be true for a child without personality factors that change the way they respond to environmental influences. What if the child is high in callous-unemotional traits? It is known from prior research that children who are most aggressive also display high levels of callous-unemotional traits (Fanti et al. 2009). These traits may play an important role in determining how young people will react to different parenting styles. In relation to this, the current article proposes that permissive parenting may increase the chances for high callous-unemotional children to perpetrate parent-directed aggression as they may learn that being aggressive will enable them to dominate their parents. In contrast, aggressive children who are low in callous-unemotional traits may specialize in aggression in the home, primarily in response to a harsh and hostile parenting style. There is a need to examine whether child-to-parent aggression plays a proactive function in families characterized by permissive parenting and a reactive function in families with other parenting styles (Calvete et al. 2013).

A cross-sectional study conducted with a community sample found psychopathic traits moderated the effect of parental affection on aggression (Yeh et al. 2011). The multi-level regression models were applied in data analysis. First, positive parenting was able to decrease reactive aggression among young people low on psychopathic traits. Second, young people who were high on psychopathic traits had stable reactive aggression regardless of parental affection. Third, an independent effect of negative parenting was found on proactive aggression among young people high on psychopathic traits. Therefore, the effect of parenting styles on aggression was dependent on the level of psychopathic traits in young people.

Callous-unemotional traits are a component of psychopathic traits. As with psychopathy in adults, adolescents who are high on callous-unemotional traits are less responsive to punishment but are more responsive to reward-based discipline techniques (Hawes and Dadds 2005). Problem behavior was found to be less related to parenting when callous-unemotional traits were present (Edens et al. 2008; Hipwell et al. 2007; Oxford et al. 2003). So, it is possible that when the young person is high on callous-unemotional traits, harsh and inconsistent parenting is not related to child-to-parent aggression. Indeed, Oxford et al. (2003) claimed that children with high callous-unemotional traits are less influenced by parents’ efforts to discipline them. Contrastingly, Muñoz et al. (2011) found that withdrawing parental control had an effect on conduct problems and delinquency among young people who are high on callous-unemotional traits. This finding is in line with the hypothesis of the present article that permissive parenting may increase the risk for high callous-unemotional young people to perpetrate aggression toward them.

Indeed, permissive parenting leads to aggression in general samples (Parke and Buriel 1998; Paulson et al. 1990). Permissive parenting also demonstrates an overly supportive home environment that nurtures proactive aggression (Dodge 1991). Wachs (1992) argued that parents tend to get annoyed by aggressive children regardless of the subtype (i.e., proactive or reactive aggression). Parents may then resort to using harsh parenting to combat child aggression, although it results in a coercive exchange. Xu et al. (2009) found that harsh parenting contribute to children’s proactive and reactive aggression. However, permissive parenting tends to be associated with proactive, but not reactive aggression.

In sum, young people with high callous-unemotional traits tend to show more severe and stable aggressive behavior than those without these traits (Byrd et al. 2012; Muñoz and Frick 2012; Perenc and Radochonski 2014). Those with callous-unemotional traits were found to be more likely to perpetrate aggression toward peers and others (Fanti et al. 2009; Kimonis et al. 2008). If they have a higher tendency to be aggressive toward their peers, they may victimize those who are significant to them—their family members. However, to date, no known study has examined the relationship between callous-unemotional traits and child-to-parent aggression. It can be argued that callous-unemotional traits should be considered as a potential contributor to family aggression and to child-to-parent aggression in particular.

Callous-Unemotional Traits and Parent-Directed Aggression: A New Direction

The previous sections looked at the prevalence of child-to-parent aggression and explored parenting styles in relation to parent-directed aggression. Further, children high on callous-unemotional traits were argued to perpetrate aggression toward their parents even though they might not be mistreated by parents. The current section will examine callous-unemotional traits and how they relate to parent-directed aggression. Callous-unemotional traits (i.e., uncaring, lack of guilt and empathy, callous use of others) have been found to be relatively stable from childhood to adolescence (Burke et al. 2007; Frick and White 2008). Additionally, they are empirically among the contributing factors to severe antisocial behavior, which include aggression (Frick and Dickens 2006). Aggression may be divided into two types: proactive and reactive. Proactive aggression (i.e., instrumental aggression) is described as deliberate actions with the aim to achieve a desired goal. In other words, it is a type of aggression that is predatory and used for personal gains (i.e., to achieve physical, social, and psychological goals) (Card and Little 2006; Hubbard et al. 2010). In contrast, reactive aggression represents a reaction to a perceived threat and is characterized by intense anger (Dodge and Coie 1987; Hubbard et al. 2010; Vitaro et al. 2006; Xu et al. 2009). It involves loss of emotional and behavioral control (Barratt et al. 1999; Berkowitz 1993). Studies on peer aggression show that aggressive behavior is motivated by two main reasons; either to pursue an instrumental goal (proactive aggression) or to seek revenge toward a provocateur (reactive aggression) (Dodge and Pettit 2003). Proactive aggressors tend to use aggression for social gain and dominance and they also have positive thoughts about the usefulness of aggression, and show less negative emotions when acting aggressively (Dodge 1991). Callous-unemotional traits relate to both proactive and reactive forms of aggression. For instance, young people with high callous-unemotional traits tend to show a more serious and pervasive aggressive behavior, and their aggression tends to be both proactive and reactive (Fanti et al. 2009; Frick et al. 2003; Kruh et al. 2005). Notably, youth with low callous-unemotional traits are less aggressive in general and, when they are aggressive, their behavior tends to be more reactive in nature (Frick et al. 2003; Kruh et al. 2005). Among incarcerated youth, those with higher levels of proactive aggression have higher callous-unemotional traits (Frick et al. 2003; Frick and Marsee 2006). Therefore, children who persist in using high levels of aggression throughout childhood may be high on callous-unemotional traits and may perpetrate aggression indiscriminately, with or without provocation and even toward peers and others.

Past researchers have tended to explain reactive aggression as related to a failure in cognitive processing of social information during decision making. It is sometimes informally referred to as “hot blooded” aggression (Dodge et al. 1997; Dodge and Pettit 2003; Lemerise and Arsenio 2000). Social Information Processing theory focuses on how young people process information cognitively and emotionally when they interact with others, especially when problems arise in their social interactions. According to this theory, aggressive children process information differently from their non-aggressive peers (Crick and Dodge 1994). Due to the failure to effectively process social information, young people were unable to give appropriate responses to social situations, which could be the reason why they used aggression (Crick and Dodge 1994; Dodge 1986). It can be argued that those who are high on callous-unemotional traits may also differ from their peers who are low on callous-unemotional traits in information processing (i.e., adolescents with low callous-unemotional traits may perceive a situation as provocative although their high callous-unemotional peers may not perceive it the same way). In contrast, proactive aggression is characterized as a deficit in defensive motivations - called “cold-blooded” aggression (Houston et al. 2004). The Social Information Processing model explained the discrepancy between reactive and proactive aggression and this may hold true for adolescents high on callous-unemotional traits: using aggression may be a rational choice rather than resulting from an inability to control their anger (Crick and Dodge 1996; Dodge 1991). Using proactive aggression, the high callous-unemotional individual may seek to dominate others. Young people with both proactive and reactive aggression are aggressive even without provocation, and are moderately higher on callous-unemotional traits (Muñoz et al. 2008), which shows the importance of determining the levels of callous-unemotional traits among aggressive young people.

Despite the evidence of callous-unemotional traits relating to aggressive behavior, callous-unemotional traits curiously do not appear to have been studied in research on domestic violence. The closest finding in this area is a study conducted by Calvete et al. (2013) with 1072 adolescents on the predictors of child-to-parent aggression. Child-to-parent aggression was found to be predicted by proactive, but not reactive aggression. Child-to-parent aggression was motivated by intentions to cause physical, financial, or psychological harm to parents. As discussed above, children with high levels of callous-unemotional traits use both proactive and reactive aggression while those with low callous-unemotional traits tend to use only reactive aggression (Fanti et al. 2009; Frick et al. 2003; Mayberry and Espelage 2007). It is possible that young people who are high on callous-unemotional traits perpetrate proactive aggression on their parents to achieve dominance, while those low on callous-unemotional traits perpetrate aggression to seek revenge against harsh treatment by parents. In a longitudinal study conducted on a Canadian community sample, parents practicing harsh parenting styles were perceived as demeaning and degrading, which then generate refutation by adolescents, especially from those who never developed appropriate anger management strategies (Pagani et al. 2009). These young people are suggested to reflect the part of the “Trait-Based Model” that focuses on children low on callous-unemotional traits (Fig. 1). It is argued that those with high callous-unemotional traits are “generalists” and tend to perpetrate aggression toward peers and their parents, while those low on callous-unemotional traits are “specialists” and their aggression occurs as a reaction toward provocation or harsh parenting. In terms of child-to-parent aggression context, young people may think that it is unfair for parents to take control of situations, and they may try to gain independence (Pagani et al. 2009) from their parents and one way to do this is by perpetrating aggression on parents. There is no widely agreed answer to the question about why a child is aggressive toward a parent (Routt and Anderson 2015). In the next section, motivations that may well relate to the perpetration of aggression will be further examined to inform the proposed model of child-to-parent aggression.

Social Goals and Link with Callous-Unemotional Traits: An Important but Overlooked Area

In this section, the focus is on callous-unemotional traits and goal orientations when a young person perpetrates aggression—the discussion will extend this to parents as victims. Young people who perpetrate aggression, especially toward their parents, may be driven by different goals, depending on their level of callous-unemotional traits. As discussed earlier, those with low levels of callous-unemotional traits are more likely to perpetrate reactive aggression and their goal may be to seek revenge for harsh parenting received. In contrast, those who are high on these traits tend to perpetrate proactive aggression with the goal to dominate. The framework of Social Learning Theory (Bandura 1977) proposed that people act based on their expectations of outcomes. In other words, they will behave according to what they believe will lead them to achieving their goals (Calvete 2007). These goals can be divided into four distinct categories, which are to gain dominance, revenge, affiliation, or to avoid problems with others (Lochman et al. 1993). Within family relationships, especially with parents, these goals may apply differentially depending on the youth’s level of callous-unemotional traits. In general, young people with high callous-unemotional traits may be aggressive toward their parents to exercise power and to control them (Holt 2016), in other words, to dominate. This, however, is not as likely to happen among those without significant callous-unemotional traits as dominance may not be the main motivation for their aggression. They are more likely to perpetrate aggression out of anger and an inability to control their emotion (Eisenberg et al. 2010).

Social goals signify the result of a problem-solving process, which is an important factor to understand the underlying factor that motivates a person to behave in certain ways. Lochman et al. (1993) examined how goals and problem-solving decisions differ among boys who were high and low in aggression. They found boys who were rated by their teachers as high on depression and aggression, and low on sociability also rated themselves as high on social goals of revenge and dominance and low on affiliation goals. Boys who rated themselves as high on revenge and dominance goals with low affiliation goals were rated by their peers as lacking in attention, more aggressive, and least liked among their peers. Aggressive behavior was positively related to antisocial goals, while prosocial goals were negatively related to aggressive behavior (Samson et al. 2012). This also demonstrates close association between social goals or motives and behavioral strategies that young people use (Li and Wright 2014). As proposed in the “Trait-Based Model”, aggressive young people are expected to choose antisocial over prosocial goals. It is, thus, argued that two types of aggression perpetrators; the “generalists” who are high on callous-unemotional traits who also tend to be motivated by the goal to dominate others using aggression, and the “specialists” who are low on callous-unemotional traits who are more likely to perpetrate aggression to seek revenge for harsh parenting.

Interestingly, Pardini (2011) found a similar result to Li and Wright’s (2014) community sample, in his study with 156 adjudicated adolescents between the ages of 11–18 years. Based on self-reported data, juveniles who scored high on callous-unemotional traits and prior violence also scored higher on antisocial goals and low on prosocial goals. Adolescents who scored high on callous-unemotional traits did not expect their victim to suffer physically or emotionally from their aggressive behavior, which may explain why they continue to behave aggressively. Prior violence also did not predict the expectations or values regarding victim suffering as a result of aggression. This further strengthens the argument that aggression is related to revenge and dominance as social goals. Furthermore, if these goals relate to peer aggression among adolescents with high callous-unemotional traits, this might also explain aggression toward parents. For example, assaultive youth were found to have limited emotional attachments to their parents (Agnew and Huguley 1989). Their assaultive behavior may be explained by having abusive parents or being a witness of domestic violence (Brezina 1999). Being a victim of abuse or witnessing one parent abusing the other may lead to the desire to seek revenge on the abusive parent, to take revenge on behalf of the abused parent, or to follow the lead of the abusive parent by abusing the parent-victim. Indeed, studies have found that parents who were abused by their partner have a tendency to be abused by their children (Downey 1997; Ulman and Straus 2003). Young people learned that they could exercise control or power over their parents (especially their mothers) by abusing them (Cottrell and Monk 2004). The situation is exacerbated by the fact that these parents do not receive support from professionals even if they do complain about their child-to-parent aggression experiences (Dahlitz 2015; Evans and Warren-Scholberg 1988).

Although prior studies have linked social goals with aggression, to date there has not been a particular study that directly addresses this issue within the domestic violence context. Some evidence can be garnered, however, from Purcell et al. (2014) who found that perpetrators had been aggressive for months or years prior to a parent’s application for a court order. From their records, more than 10% of the perpetrators committed premeditated aggression to apparently scare their sibling or to obtain something beneficial (e.g., money or alcohol) from their parents. Only 8% of the cases happened after being provoked by the victim. Moreover, Calvete et al. (2014) interviewed adolescents, parents, and professionals from a focus group for families experiencing parent-directed aggression. Among other topics, adolescents also stated that they learned that aggression was necessary to take control of their parents, and most importantly to gain respect. The findings showed that young people view aggression as a tool to bring them closer to their goals. Thus, it is also important to measure social goals in studies of domestic violence, particularly when the child is the perpetrator.

A New Model of the Two Types of Aggression by Children Against Parents and its Implications

As discussed in each section above, the aim is to introduce a new “Trait-Based Model” to further explain parent-directed aggression, focusing on the perpetrators. In the model (Fig. 1), two types of perpetrators of child-to-parent aggression are proposed: “generalists” and “specialists”. First, “generalists” perpetrators are proposed to be high on callous-unemotional traits and they do not target their aggression toward one person, but do so toward many people including parents, siblings, and peers. In contrast, “specialists” perpetrators are those low on callous-unemotional traits and they only specialize in victimizing parent(s). Second, “generalists” perpetrate proactive aggression, which is a pre-planned aggression normally motivated by their goal to dominate others that they generalize from peers to their parents and siblings. In contrast, “specialists” perpetrate primarily reactive aggression, which is a response toward provocation normally motivated by their goal to seek revenge, including parent(s) (father or mother or both). Third, the model also proposes that “generalists” are nurtured by permissive parenting. Parents who are over-indulgent in parenting their child might lead to proactively aggressive child who will “rule the roost” with aggression. In contrast, “specialists” are nurtured by harsh parenting.

The “Trait-Based Model” has significant potential implications for treatment. Holt (2013) has made a useful summary of the established parent abuse intervention programs and approaches that have been used in countries including Australia, Canada, USA, and the UK. Some of the group intervention programs that concentrate on both parent and child have been implemented in the UK. One of them is the “Break4Change”, which aims to stop violence within the home and develop more positive relationship between family members. The program focuses on teaching parents the skills to manage their emotions with regards to abuse experiences. In addition, it includes teaching young people on emotional regulation, the impact of violence and abuse, and developing skill in impulse control and resolving conflict (Munday 2009). A similar program called the “SAAIF”, which aims include providing tools for young person to deal with anger and aggression, has been used in the UK. It was found to be helpful for parents, young person and stakeholders, in particular for learning new communication skills and coping strategies (Priority Research 2009). Another example of family intervention that has been implemented for young people who perpetrate parent-directed aggression is the Nonviolent Resistance (NVR). NVR is a method introduced by Omer (2004) that offers parents knowledge to deal with their children in a diplomatic and non-violent way (e.g., delay responses, increasing parental presence, de-escalating situations, and letting trusted people know about the problems to gather social support in resisting violent and controlling behaviors) instead of trying to handle aggressive behavior with more aggression.

If the “Trait-Based Model” is correct, however, interventions that focus on family therapy or focusing on the parent–child relationship therapeutically may work better for young person who are “specialists”. For the “generalists” who are high on callous-unemotional traits, an intervention should tap into the role of containment and shaping behavior through reward. One program that attempts to use behavior modification techniques is the “Step Up” program (Buel 2002). The program uses cognitive–behavioral approach and making the perpetrators accountable for their doings and keeping the victims safe. The aims are to challenge attitudes and beliefs, develop the young person’s skills that include empathy, alongside with using peer support and feedback. However, rather than including a reward component, this program uses punishment such as an overnight detention if the young person does not engage with the intervention program. Although it could be viewed as a powerful learning exercise for adolescents (Robinson 2011), it is a great concern as young people who are high on callous-unemotional traits do not respond to punishment but respond positively to rewards (Kimonis et al. 2012). Perhaps the punishment part can be replaced with rewarding the involved young people with positive reinforcement (i.e., rewarding them with praise or treats if they show good progress and engage positively in the program). It is therefore important to distinguish the “generalists” from the “specialists” because, by doing this, intervention can be offered accordingly—depending on the young person’s level of callous-unemotional traits.

Limitations of Research and Suggestions for Future Researchers

Research on child-to-parent aggression is limited especially in the UK. Conducting research in this area can be challenging. Past attempts to examine child-to-parent aggression were limited to small-scale therapeutic groups or via court records. Relying solely on data from court records or adjudicated samples may lead to biased findings. Also, parents tend to withdraw applications for court orders and court protections for domestic violence. In addition, there are parents who never apply for orders despite experiencing violence from their adolescents. Parents may be afraid of the consequences of calling “999” for help, because as a parent, they are supposed to be protecting their children, and not criminalizing them (Holt and Retford 2013). It is also possible that court cases may only reflect “generalists” in aggression—those who perpetrate aggression toward parents, siblings, peers, and others (i.e., their involvement with the criminal justice system may be due to criminal aggression against non-parent targets). So, other options should be taken into consideration to collect data on child-to-parent aggression. Although it is believed physical aggression toward parents may be less common among adolescents compared to younger children, it is still necessary to distinguish adolescents who physically abuse their parents. Problems may get more serious when the child enters adolescence because their size and strength might rival that of their parents, which may increase the risk of physical injury. Besides, most local authorities and frontline practitioners do not have the policy guidance or framework to deal with child-to-parent aggression. It is also somewhat unusual despite having evidence of the prevalence of parent-directed aggression, both from general and clinic-referred samples, this form of abuse has yet to be considered a “social problem”. Parents who have sought help from frontline services (e.g., police, judiciary, social care services, health services, non-government organization) are often disappointed with the perceived poor effectiveness of the response received (Holt and Retford 2013). Research conducted in several countries, including the UK, to examine parents’ experiences of child aggression has confirmed this is indeed true (Eckstein 2004; Haw 2010; Holt 2011; Hunter et al. 2010; Parentline Plus 2010).

Although prior studies showed adolescents from mental health units perpetrate more aggression toward parents as compared to community samples, little is known about the mechanisms that contribute to aggressive behavior. Condry and Miles (2014) claimed the development of child-to-parent aggression is very complex and a direct framework is needed to address this issue. While recent research has considered aggression perpetrated by adolescents toward parents, perpetrators were not surveyed to explore the possible mechanisms. Instead, findings are limited to answers young people may have to questions asked by authority figures (i.e., police). It is not clear whether their aggression was due to their intention to be in control of their parents or to get revenge on parents who were harsh to them. Also, since child-to-parent aggression is rarely reported voluntarily by parents or adolescents, direct questions about child-to-parent aggression would need to be asked during one-on-one interview sessions. Thus, more studies are needed to address these limitations. It is also crucial to develop a model of child-to-parent aggression to help develop effective and systematic interventions for individuals, parents, and families.

In this review, it is argued that callous-unemotional traits play an important role in young people’s development of aggression. The level of these traits in young people may have been inherited from parents—meaning that if the parents are also high in these traits, the young people will be too. In fact, there is a growing literature on the heritability of callous-unemotional traits/psychopathy. Also, parents may be more likely to use negative parenting styles if they are high on callous-unemotional traits themselves. So, it would be worthwhile to examine parents’ callous-unemotional traits in future studies. Being exposed to violence especially at home reinforce the possibility of becoming a home violence perpetrator in the future. Although some studies have investigated this, callous-unemotional traits were not considered. As discussed, it may matter whether or not the child is high on the traits, as they would react to parenting styles differently than their low callous-unemotional traits peers. Most importantly, considering callous-unemotional traits could help the parents to learn how to support the adolescents when they are experiencing a difficult period. That may then help to reduce the risk of abuse toward parents. Therefore, more research is needed to explore the mechanisms and risk factors of child-to-parent aggression.

Conclusions

This review intended to highlight the important risk factors of child-to-parent aggression and to encourage future research in this area to understand the mechanisms of aggression toward parents. This article contributed to a novel explanation for parent-directed aggression by taking into account the level of callous-unemotional traits of the perpetrators. As discussed throughout the article and also through the “Trait-Based Model”, it is possible that youth with high callous-unemotional traits choose to abuse their parents for personal gain, or merely to dominate the household. It could also be that parents who use corporal punishment might have children who use aggression—it is argued that this applies to those low on callous-unemotional traits. Despite the lack of research to show whether young people’s aggression at home is more reactive or proactive, Routt and Anderson (2015) claimed that based on their experience, young people use both styles. However, proactive or reactive aggression depend on the perpetrator’s level of callous-unemotional traits. The “Trait-Based Model” demonstrates that, in order to reduce the risk and the prevalence of child-to-parent aggression, “one size fits all” solutions cannot work. Instead, targeted intervention or treatment plans need to be implemented based on the type of perpetrator.

References

Agnew, R., & Huguley, S. (1989). Adolescent violence toward parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51(3), 699–711.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Barlow, J., Davis, H., McIntosh, E., Jarrett, P., Mockford, C., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). Role of home visiting in improving parenting and health in families at risk of abuse and neglect: Results of a multicentre randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 92(3), 229–233. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.095117.

Barratt, E. S., Stanford, M. S., Dowdy, L., Liebman, M. J., & Kent, T. A. (1999). Impulsive and premeditated aggression: A factor analysis of self reported acts. Psychiatry Research, 86, 163–173.

Baumrind, D. (1967). Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 75(1), 43–88.

Benzies, K., & Mychasiuk, R. (2009). Fostering family resiliency: A review of the key protective factors. Child and Family Social Work, 14(1), 103–114. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2008.00586.x.

Berkowitz, L. (1993). Aggression: Its causes, consequences, and control. New York: Academic Press.

Bornstein, M. H. (2002). Handbook of parenting. Volume 5: Practical issues in parenting. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Boxer, P., Gullan, R. L., & Mahoney, A. (2009). Adolescents’ physical aggression toward parents in a clinic-referred sample. Journal of Clinical and Adolescent Psychology, 38, 106–116. doi:10.1080/15374410802575396.

Brezina, T. (1999). Teenage violence toward parents as an adaptation of family strain. Youth and Society, 30(4), 416–444.

Buel, S. M. (2002). Why juvenile courts should address family violence: Promising practices to improve intervention outcomes. Juvenile and Family Court Journal, 53(2), 1–16.

Burke, J. D., Loeber, R., & Lahey, B. B. (2007). Adolescent conduct disorder and interpersonal callousness as predictors of psychopathy in young adults. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36, 334–346.

Byrd, A. L., Loeber, R., & Pardini, D. A. (2012). Understanding desisting and persisting forms of delinquency: The unique contributions of disruptive behavior disorders and interpersonal callousness. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 53, 371–380. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02504.x.

Calvete, E. (2007). Justification of violence beliefs and social problem-solving as mediators between maltreatment and behavior problems in adolescents. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 10, 131–140. doi:10.1017/S1138741600006399.

Calvete, E., Orue, I., Bertino, L., Gonzalez, Z., Montes, Y., Padilla, P., & Pereira, R. (2014). Child-to-parent violence in adolescents: The perspectives of the parents, children, and professionals in a sample of Spanish focus group participants. Journal of Family Violence, 29, 343–352.

Calvete, E., Orue, I., & Gamez-Guadix, M. (2013). Child-to-parent violence: Emotional and behavioral predictors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(4), 755–772. doi:10.1177/0886260512455869.

Card, N. A., & Little, T. D. (2006). Proactive and reactive aggression in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis of differential relations with psychosocial adjustment. International Journal of Behavior Development, 30(5), 466–480.

Charles, A. V. (1986). Physically abused parents. Journal of Family Violence, 1(4), 343–355.

Condry, R., & Miles, C. (2014). Adolescent to parent violence: Framing and mapping a hidden problem. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 14(3), 257–275. doi:10.1177/1748895813500155.

Contreras, L., & Cano, C. (2014). Family profile of young offenders who abuse their parents: A comparison with general offenders and non-offenders. Journal of Family Violence, 29(8), 901–910. doi:10.1007/s10896-014-9637-y.

Coogan, D. (2011). Child-to-parent violence: Challenging perspectives on family violence. Child Care in Practice, 17(4), 347–358.

Cottrell, B. (2001). Parent abuse: The abuse of parents by their teenage children. Ottawa: Health.

Cottrell, B., & Monk, P. (2004). Adolescent-to-parent abuse: A qualitative overview of common themes. Journal of Family Issues, 25(8), 1072–1095. doi:10.1177/0192513X03261330.

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 74–101.

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1996). Social information-processing mechanisms in reactive and proactive aggression. Child Development, 67(3), 993–1002.

Dahlitz, M. (2015). A theoretical commentary of parent abuse and intersibling violence from both neurobiological and social perspectives. Neuropsychotherapist, 13, 18–27.

Dodge, K. A. (1986). A social information processing model of social competence in children. In M. Perlmutter (Ed.) Minnesota symposium on child psychology. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Dodge, K. A. (1991). The structure and function of reactive and proactive aggression. In D. Peppler & K. Rubi (Eds.), The development and treatment of childhood aggression (pp. 201–218). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Dodge, K. A., & Coie, J. D. (1987). Social-information-processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(6), 1146–1158. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1146.

Dodge, K. A., Lochman, J. E., Harnish, J. D., Bates, J. E., & Pettit, G. S. (1997). Reactive and proactive aggression in school children and psychiatrically impaired chronically assaultive youth. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(1), 37–51.

Dodge, K. A., & Pettit, G. S. (2003). A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 39, 349–371.

Downey, L. (1997). Adolescent violence: A systemic and feminist perspective. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 18(2), 70–79.

Eckstein, N. J. (2004). Emergent issues in families experiencing adolescent-to-parent abuse. Western Journal of Communications, 68(4), 365–388.

Edens, J. F., Skopp, N. A., & Cahill, M. A. (2008). Psychopathic features moderate the relationship between harsh and inconsistent parental discipline and adolescent antisocial behavior. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 472–476.

Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., & Eggum, N. D. (2010). Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 495–525.

Eriksen, S., & Jensen, V. (2006). All in the family? Family environment factors in sibling violence. Journal of Family Violence, 21(8), 497–507. doi:10.1007/s10896-006-9048-9.

Evans, E. D., & Warren-Scholberg, L. (1988). A pattern analysis of adolescent abusive behavior toward parents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 3, 200–216.

Fanti, K. A., Frick, P. J., & Georgiou, S. (2009). Linking callous-unemotional traits to instrumental and non-instrumental forms of aggression. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31(4), 285–298. doi:10.1007/s10862-008-9111-3.

Farrington, D. P., Coid, J. W., Harnett, L., Jolliffe, D., Soteriou, N., Turner, R., & West, D. J. (2006). Criminal careers and life success: new findings from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development (2nd edn.). London: Research Development and Statistics in the Home Office.

Frick, P. J., Cornell, A. H., Bodin, S. D., Dane, H. E., Barry, C. T., & Loney, B. R. (2003). Callous-unemotional traits and developmental pathways to severe conduct problems. Developmental Psychology, 39, 246–260.

Frick, P. J., & Dickens, C. (2006). Current perspectives on conduct disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 8, 59–72.

Frick, P. J., & Marsee, M. A. (2006). Psychopathy and developmental pathways to antisocal behavior in youth. In C. J. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of psychopathy (pp. 353–374). New York: Guilford Press.

Frick, P. J., & White, S. F. (2008). Research review: The importance of callous-unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 49(4), 359–375. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01862.x.

Gallagher, E. (2008). Children’s violence to parents: A critical literature review. Melbourne: Monash University.

Gallagher, E. (2009). Children’s violence to parents. Retrieved February 20, 2017 from http://www.noviolence.com.au/public/seminarpapers/gallagherslides.pdf.

Gov. UK Home Office. (2016). Guidance: Domestic violence and abuse. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/guidance/domestic-violence-and-abuse. Accessed 30 Mar 2017.

Harbin, H. T., & Maddin, D. J. (1979). Battered parents: A new syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry, 136, 1288–1291.

Hawes, D. J., & Dadds, M. R. (2005). The treatment of conduct problems in children with callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 737–741. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.737.

Herbert, M. (2004). Parenting across the lifespan. In M. Hoghughi & N. Long (Eds.), Handbook of parenting: Theory and research for practice (pp. 55–71). London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Hipwell, A. E., Pardini, D. A., Loeber, R., Sembower, M., Keenan, K., & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (2007). Callous-unemotional behaviors in young girls: Shared and unique effects relative to conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36(3), 293–304.

Hoeve, M., Stams, G. J. J. M., Van Der Put, C. E., Dubas, J. S., Van Der Laan, P. H., & Gerris, J. R. M. (2012). A meta-analysis of attachment to parents and delinquency. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(5), 771–785. doi:10.1007/s10802-011-9608-1.

Holt, A. (2011). The terrorist in my home: Teenagers violence towards parents—constructions of parent experiences in public online message boards. Child and Family Social Work, 16(4), 454–463.

Holt, A. (2013). Adolescent-to-parent abuse: Current understandings in research, policy and practice. Bristol: Policy Press.

Holt, A. (2016). Working with adolescent violence and abuse towards parents: Approaches and contexts for intervention. London: Routledge.

Holt, A., & Retford, S. (2013). Practitioner accounts of responding to parent abuse—a case study in ad hoc delivery, perverse outcomes and a policy silence. Child and Family Social Work, 18, 365–374.

Hong, J. S., Kral, M. J., Espelage, D. L., & Allen-Meares, P. (2012). The social ecology of adolescent-initiated parent-abuse: A review of the literature. Child Psychiatry Human Development, 43, 431–454.

Houston, R. J., Stanford, M. S., Villemarette Pittman, N. R., Conklin, S. M., & Helfritz, L. E. (2004). Neurobiological correlates and clinical implications of aggressive subtypes. Journal of Forensic Neuropsychology, 3(4), 67–87.

Howard, J. (2011). Adolescent violence in the home—the missing link in family violence prevention and response. Sydney: Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse.

Hubbard, J. A., McAuliffe, M. D., Morrow, M. T., & Romano, L. J. (2010). Reactive and proactive aggression in childhood and adolescence: Precursors, outcomes, processes, experiences, and measurement. Journal of Personality, 78(1), 95–118.

Hunter, C., & Nixon, J. (2012). Exploring parent abuse: Building knowledge across disciplines. Social Policy and Society, 11, 211–215.

Hunter, C., Nixon, J., & Parr, S. (2010). Mother abuse: a matter of youth justice, child welfare, or domestic violence? Journal of Law and Society, 37(2), 264–284.

Ibabe, I., & Jaureguizar, J. (2010). Child-to-parent violence: Profile of abusive adolescents and their families. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(4), 616–624. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.04.034.

Ibabe, I., & Jaureguizar, J. (2011). ¿Hasta qué punto la violencia filio-parental es bidireccional? [To what extent is child-to-parent violence bi-directional?]. Anales de Psicología, 27(2), 265–277.

Ibabe, I., Jaurequizar, J., & Díaz, O. (2009). Adolescent violence against parents. Is it a consequence of gender inequality? The European Journal of Psychology of Applied to Legal Context, 1(1), 3–24.

Kennair, N., & Mellor, D. (2007). Parent abuse: A review. Child Psychiatry Human Development, 38(3), 203–219. doi:10.1007/s10578-007-0061-x.

Kennedy, T. D., Edmonds, W. A., Dann, K. T. J., & Burnett, K. F. (2010). The clinical and adaptive features of young offenders with histories of child-parent violence. Journal of Family Violence, 25, 509–520. doi:10.1007/s10896-010-9312-x.

Kethineni, S. (2004). Youth-on-parent violence in a central Illinois county. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 2(4), 374–394.

Kimonis, E. R., Frick, P. J., Cauffman, E., Goldweber, A., & Skeem, J. (2012). Primary and secondary variants of juvenile psychopathy differ in emotional processing. Development and Psychopathology, 24, 1091–1103. doi:10.1017/S0954579412000557.

Kimonis, E. R., Frick, P. J., Skeem, J. L., Marsee, M. A., Cruise, K., Centifanti, L. C., Morris, A. S., et al. (2008). Assessing callous-unemotional traits in adolescent offenders: Validation of the inventory of CU traits. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 31(3), 241–252. doi:10.1136/bmj.c4564.

Kruh, I. P., Frick, P. J., & Clements, C. B. (2005). Historical and personality correlates to the violence patterns of juveniles tried as adults. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 32, 69–96.

Kuay, H. S., Lee, S., Centifanti, L. C. M., Parnis, A. C., Mrozik, J. H., & Tiffin, P. A. (2016). Adolescents as perpetrators of aggression within the family. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 47, 60–67. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.02.035.

Landsverk, J., Carrilio, T., Connelly, C. D., Ganger, W. C., Slymen, D. J., Newton, R. R., & Al., E (2002). Healthy families San Diego clinical trial technical report. San Diego: Child and Adolescent Services Research Center, San Diego Children’s Hospital and Health Center.

Lemerise, E. A., & Arsenio, W. F. (2000). An integrated model of emotion processes and cognition in social information processing. Child Development, 71(1), 107–118.

Li, Y., & Wright, M. F. (2014). Adolescents’ social status goals: Relationships to social status insecurity, aggression, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 146–160. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9939-z.

Lochman, J. E., Wayland, K. K., & White, K. J. (1993). Social goals: relationship to adolescent adjustment and to social problem solving. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 21(2), 135–151.

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent–child interaction. In P. H. Mussen, & E. M. Hetherington (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development (pp. 1–101). New York: Wiley.

Marcus, R. F., & Betzer, P. D. (1996). Attachment and antisocial behavior in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 16(2), 229–248.

Margolin, G., & Baucom, B. R. (2014). Adolescents’ aggression to parents: Longitudinal links with parents’ physical aggression. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55, 645–651.

Martínez, M. L., Estévez, E., Jiménez, T. I., & Velilla, C. (2015). Child-parent violence: main characteristics, risk factors and keys to intervention. Papeles Del Psicólogo, 36(3), 216–224.

Mayberry, M. L., & Espelage, D. L. (2007). Associations among empathy, social competence, & reactive/proactive aggression subtypes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 787–798.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701.

Munday, A. (2009). Break4Change: Does a holistic intervention effect change in the level of abuse perpetrated by young people towards their parents/carers? Unpublished BA (Hons) Professional Studies in Learning and Development dissertation. Sussex: University of Sussex.

Muñoz, L. C., & Frick, P. J. (2012). Callous-unemotional traits and their implication for understanding and treating aggressive and violent youths. Criminal Justice and Behavior 39(6), 794–813. doi:10.1177/0093854812437019.

Muñoz, L. C., Frick, P. J., Kimonis, E. R., & Aucoin, K. J. (2008). Types of aggression, responsiveness to provocation, and callous-unemotional traits in detained adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 15–28. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9137-0.

Muñoz, L. C., Pakalniskiene, V., & Frick, P. J. (2011). Parental monitoring and youth behavior problems: Moderation by callous-unemotional traits over time. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 20, 261–269. doi:10.1007/s00787-011-0172-6.

Nock, M. K., & Kazdin, A. E. (2002). Parent-directed physical aggression by clinic-referred youths. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 31(2), 193–205.

Office of the Public Guardian. (2015). Safeguarding policy. Birmingham. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/595194/SD8-Office_of-the-Public-Guardian-safeguarding-policy.pdf. Accessed 30 Mar 2017.

Olds, D. L. (2002). Prenatal and infancy home visiting by nurses: From randomized trials to community replication. Prevention Science, 3(3), 153–172. doi:10.1023/A:1019990432161.

Olds, D. L., Pettitt, L. M., Robinson, J., Henderson, C. Jr. Eckenrode, J., Kitzman, H., Cole, B., & Powers, J. (1998). Reducing risks for antisocial behavior with a program of prenatal and early childhood home visitation. Journal of Community Psychology, 26, 65–83.

Olds, D. L., Sadler, L., & Kitzman, H. (2007). Programs for parents of infants and toddlers: Recent evidence from randomized trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(3–4), 355–391. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01702.x.

Omer, H. (2004). Nonviolent Resistance: A New Approach to Violent and Self-Destructive Children. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Oxford, M., Cavell, T. A., & Hughes, J. N. (2003). Callous-unemotional traits moderate the relation between ineffective parenting and child externalizing problems: A partial replication and extension. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 577–585.

Pagani, L., Tremblay, R., Nagin, D., Zoccolillo, M., Vitaroa, F., & McDuff, P. (2004). Risk factor models for adolescent verbal and physical aggression toward mothers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(6), 528–537.

Pagani, L., Tremblay, R. E., Nagin, D., Zoccolillo, M., Vitaro, F., & McDuff, P. (2009). Risk factor models for adolescent verbal and physical aggression toward fathers. Journal of Family Violence, 24(3), 173–182. doi:10.1007/s10896-008-9216-1.

Parentline Plus. (2010). When family life hurts: Family experience of aggression in children. London: Parentline Plus. Retrieved from http://www.familylives.org.uk/media_manager/public/209/Documents/Reports/When family life hurts 2010.pdf. Accessed 30 Mar 2017.

Pardini, D. (2011). Perceptions of social conflicts among incarcerated adolescents with callous-unemotional traits: “You”re going to pay. It’s going to hurt, but I don’t care’. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(3), 248–255.

Parke, R. D., & Buriel, R. (1998). Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), The handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (5th edn., pp. 463–552). New York: Wiley.

Paterson, R., Luntz, H., Perlesz, A., & Cotton, S. (2002). Adolescent violence towards parents: Maintaining family connections when the going gets tough. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 23, 90–100.

Patterson, G. R. (1980). Mothers: The unacknowledged victims. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 45(5), 1–49.

Paulson, M. J., Coombs, R. H., & Landsverk, J. (1990). Youth who physically assault their parents. Journal of Family Violence, 5(2), 121–133. doi:10.1007/BF00978515.

Perenc, L., & Radochonski, M. (2014). Psychopathic traits and reactive-proactive aggression in a large community sample of polish adolescents. Child Psychiatry Human Development, 45, 464–471.

Perez, T., & Pereira, R. (2006). “Violencia filio-parental: revision de la bibliografia” [Child-parent violence: A literature review]. Revista Mosaico, 36, 10–17.

Priority Research. (2009). Evaluation of SAAIF (Stopping Aggression and Antisocial Behaviour in Families). Sheffield. Retrieved from http://www.theministryofparenting.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/1109-SAAIF-evaluation-Report.pdf. Accessed 30 Mar 2017.

Purcell, R., Baksheev, G. N., & Mullen, P. E. (2014). A descriptive study of juvenile family violence: Data from intervention order applications in a Childrens Court. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 37(6), 558–563. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2014.02.029.

Robinson, P. W. (2011). Interventions and restorative responses to address teen violence against parents. Report for the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust. Retrieved from http://www.wcmt.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrated-reports/828_1.pdf. Accessed 30 Mar 2017.

Routt, G., & Anderson, L. (2015). Adolescent violence in the home: Restorative approaches to building healthy, respectful family relationships. New York: Routledge.

Routt, G. B., & Anderson, E. A. (2011). Adolescent violence towards parents. Journal of Abuse, Maltreatment, and Trauma, 20, 1–19.

Samson, J. E., Ojanen, T., Florida, S., & Hollo, A. (2012). Social goals and youth aggression: Meta-analysis of prosocial and antisocial goals. Social Development, 21(4), 645–666. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00658.x.

Snyder, H. N., & McCurley, C. (2008). Domestic assaults by juvenile offenders. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: Office of Justice Programs.

Stewart, M., Burns, A., & Leonard, R. (2007). Dark side of the mothering role: Abuse of mothers by adolescent and adult children. Sex Roles, 56, 183–191.

Straus, M. A., Gellas, R. J., & Steinmeitz, S. K. (1980). Behind closed doors: Violence in the American family. New York: Doubleday.

Tew, J., & Nixon, J. (2010). Parent abuse: Opening up a discussion of a complex instance of family power relations. Social Policy and Society, 9, 579–589.

Ulman, A., & Straus, M. A. (2003). Violence by children against mothers in relation to violence between parents and corporal punishment by parents. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 34, 41–60.

Vazsonyi, A. T., & Flannery, D. J. (1997). Early adolescent delinquent behaviors: associations with family and school domains. Journal of Early Adolescence, 17(3), 271–293.

Vitaro, F., Brendgen, M., & Barker, E. D. (2006). Subtypes of aggressive behavior: A developmental perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30(1), 12–19.

Wachs, T. D. (1992). The nature of nurture. Newbury Park: Sage.

Walsh, J. A., & Krienert, J. L. (2007). Child–parent violence: An empirical analysis of offender, victim, and event characteristics in a national sample of reported incidents. Journal of Family Violence, 22(7), 563–574. doi:10.1007/s10896-007-9108-9.

Walsh, J. A., & Krienert, J. L. (2009). A decade of child-initiated family violence: Comparative analysis of child–parent violence and parricide examining offender, victim and event characteristics in a national sample of reported incidents, 1995–2005. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 1450–1477.

Xu, Y., Farver, J. A., & Zhang, Z. (2009). Temperament, harsh and indulgent parenting, and Chinese children’s proactive and reactive aggression. Child Development 80(1), 244–258.

Yeh, M. T., Chen, P., Raine, A., Baker, L. A., & Jacobson, K. C. (2011). Child psychopathic traits moderate relationships between parental affect and child aggression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(10), 1054–1064.

Haw, A. (2010). Parenting over violence: Understanding and empowering mothers affected by adolescent violence in the home. Perth: Patricia Giles Centre.

Acknowledgements

The first author was supported by a funding from Malaysian Ministry of Education (KPT(BS)860514295476) and Universiti Sains Malaysia Academic Staff Training Scheme (ASTS).

Author Contributions

The first author, HSK conceived of the study, designed the model and drafted the manuscript. LC contributed to the initial design of the model, writing, and revising the manuscript. PT, LB and GT contributed to the writing and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuay, H.S., Tiffin, P.A., Boothroyd, L.G. et al. A New Trait-Based Model of Child-to-Parent Aggression. Adolescent Res Rev 2, 199–211 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-017-0061-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-017-0061-4