Abstract

This study explores the impact of participation in a series of moral case deliberations (MCD) on the moral craftsmanship (MCS) of Dutch prison staff. Between 2017–2020, ten MCDs per team were implemented in three prisons (i.e., intervention group). In three other prisons (i.e., control group) no MCDs were implemented. We compared the intervention and control group using a self-developed questionnaire, administered before (pre-measurement) and after the series of MCDs (post-measurement).

Results

After the MCDs, participants scored significantly higher on 7 of the 70 items related to MCS. On some items there were significant impact differences between the various professional disciplines.

Discussion

Possible explanations for a relatively low impact are discussed. A shorter and validated questionnaire is needed in order to further study the MCS of professionals and the impact of Ethics Support Services (ESS).

Conclusions

There was a positive development on some elements of MCS after participation in a series of MCDs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Prison staff is confronted with ethically challenging situations in their practice (Schmalleger and Smykla 2014). Often ethically challenging situations are situations in which there is uncertainty or disagreement about what is the right thing to do. These situations are, and will remain, an inherent part of their professional work. Hence, experiencing ethically challenging situations does not have to be a problem: they can be seen as opportunities to learn, to reflect, to strengthen team cooperation and to improve the moral quality of their work.

We know from research that prison staff often struggle with finding a balance between the conflicting obligations of the duty to care for prisoners and the duty to protect others (Shaw et al. 2014). The current focus on incidents and finding solutions can lead to a defensive attitude and lack of moral awareness among prison staff. Furthermore, hierarchy, which is an inherent part of the work practice within prisons, can be an element that prevents staff from taking initiative and responsibility (Houwelingen et al. 2015). It is important that professionals recognize ethically challenging situations and learn to deal with them in a constructive and methodologically sound manner (Molewijk et al. 2015). In many various morally challenging work contexts, Ethics Support Services (ESS) are used to strengthen professionals’ moral competences and moral awareness, to decrease their moral distress and to improve the multidisciplinary cooperation (REFS). A specific form of ESS is moral case deliberation (MCD).

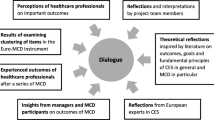

Moral case deliberation

During a MCD a group of 8–10 professionals reflect methodically and by means of a dialogue on an ethically challenging situation that has been experienced by one of them (Molewijk et al. 2008a; Weidema et al. 2013; Rasoal et al. 2016). MCD can stimulate professionals' moral competency development (Crigger et al. 2017). Under the guidance of a trained facilitator (Stolper et al. 2015), following a stepwise procedure of a specific conversation method for MCD, professionals jointly reflect on what they perceive as morally right and why, in a specific work-related situation (Molewijk et al. 2008b; Rasoal et al. 2016). A MCD is an open moral inquiry into how MCD participants can and should think about what is morally right, without the aim of convincing the other (Molewijk et al. 2008; Stolper et al. 2016). One of the purposes of MCD is to enable professionals to learn together how to deal with ethically challenging situations (Stolper et al. 2016) and improve the multidisciplinary cooperation and the quality of their work. During MCD, the facilitators do not have an advisory role on the discussed content, instead they facilitate an environment for participants to be able to feel safe and to learn to recognize the moral components of the dilemmas and stimulate moral reasoning (Stolper et al. 2016). The facilitator encourages participants to develop a dialogical attitude of mutual respect, ask open questions and postpone judgements (Weidema 2014). Studies on MCD in health care show overall positive evaluations (Hem et al. 2015; Janssens et al. 2015; Molewijk et al. 2008). Originating in health care, MCD has now found its way to other professions, such as the Armed Forces and Contra terrorism (Kowalski 2020; Van Baarle 2018).

Context and aim of the study

In 2017, a training programme was developed by the Dutch Custodial Institutions Agency (DCIA) of the Ministry of Justice and Security for all Dutch prison staff which, among other goals, aimed to support the prison staff in dealing with ethically challenging situations in their practice, and thereby increase their moral craftmanship (MCS). Within the specific prison context, by the DCIA the concept of MCS is regarded as the awareness and recognition of ethical challenges, and the competence and willingness to be open to opinions of others in a constructive way (DCIA, 2016/2017). Part of this training programme consisted of the implementation of a series of MCD sessions in which prison staff can bring up their moral challenges and jointly reflect on them through a critical yet constructive dialogue. To find out if and in which way a series of MCDs contributed to the MCS of prison staff, we developed a questionnaire that covers various elements of MCS. In this article we use the first version of the self-developed Moral Craftsmanship Questionnaire to investigate the possible impact of MCD on MCS.

Methods

Research design

Five Dutch prisons took part in this research (Leeuwarden, Vught, Almere, Nieuwegein, and Zwaag). The institutions were classified in a control group and an intervention group. MCD was implemented at the intervention locations, and no MCDs or similar training took place at control locations during this study. Initially, two prisons were assigned to the intervention group (Nieuwegein and Zwaag), and two comparable prisons to the control group (Almere and Leeuwarden). Due to the mid-2018 closures of the prisons of Zwaag and Almere—during the research period—two additional locations were selected (Leeuwarden as an intervention location and Vught as a control location). The prison of Leeuwarden therefore was first part of the control group and at a later stage of the intervention group.

Participants

We collaborated with the Educational Institute of the DCIA and the local prisons to select prisons that were willing or not willing to introduce MCD. For prisons ready to implement MCD, we selected all types of teams to have a broad representation of the organization (security guards, healthcare professionals, management team, middle management, correctional officers, case managers re-integration services, office staff re-integration services and labour instructors). Similar teams were selected for the control group.

The MCD series for the intervention groups

MCD can be facilitated and organized in many different ways. In our study some regulated settings were needed to be able to research the impact of the series. The dilemma method, a specific MCD conversation method, was used for all MCDs at DCIA (Stolper et al. 2016). The steps of this conversation method can be found in Appendix 1. For all teams in the intervention groups, we planned a series of 10 MCDs, during a period of one or one and a half year. The MCDs were scheduled for 120 to 180 min each, and were guided by one MCD facilitator of the in total 18 MCD-facilitators deployed by the Educational Institute. Each team was matched with two trained MCD facilitators, of whom most were professionally trained and certified by the ‘MCD-facilitator Training Program’ of the department of Ethics, Law and Humanities of the Amsterdam UMC (Stolper et al. 2015). All MCDs were team-based group sessions, therefore they were not multi-disciplinary. Most MCDs consisted of 5–10 participants. The manager or supervisor of the team was only present when the team explicitly requested his or her presence.

The content of the MCDs

The content of the MCDs showed to have a broad range of themes, with moral dilemmas about addressing work climate, dilemmas around suspicions of integrity breaches, or questions about whether or not to deviate from protocol. For example, if the asked medication can be given by a correctional officer to a prisoner in the isolation cell during night hours? Or they wonder to which degree hey should still carry out an assignment given by their superior, even if they do not agree with the decision made on this assignment. Additionally, many moral dilemmas showed to be about the appropriate handling of ‘security risks’, and about when or how to address situations with direct colleagues, for example: ‘Should I inform our boss about a colleague who decided to remove a prisoner from solitary confinement on her/his own against the rules, or should I confront my colleague personally? Health care professionals working in prisons showed dilemmas around their code of confidentiality versus prison security, for example: a prisoner has bruises and talks about a potential new fight, do I discuss this with the prison guards? A systematic overview of all MCD themes and dilemmas are mentioned in a recently published article (Schaap et al. 2022).

Procedure of the impact measurement

The participants of the MCD sessions received one questionnaire before the series of MCDs (pre-measurement) and one after (post-measurement). The teams in the control group received the questionnaires at the same times. The questionnaire was developed to measure various elements of MCS, which over time can possibly show the impact of an intervention, such as MCD, on MCS. The questionnaire took approximately 20 min to complete and started with nine questions about the socio-demographics of the participants (sex, age, and education) and about specific features of their employment (assignment, location at the DCIA, etc.). In the second part of the questionnaire, the participants were presented with a list of 70 items based on an explorative analysis of the relatively unknown concept of MCS. This conceptual analysis of MCS and the developmental process of the questionnaire will be published in a separate paper. We developed new items for this list, some tailored to the work practice of DCIA. We also used some items from existing questionnaires from academic literature, such as the Moral Competence Questionnaire (MCQ) (Oprins et al. 2011) or items about ‘team reflexivity’ (Schippers et al. 2005). In the end, the items of the newly developed MCS questionnaire cover topics such as moral awareness, moral reasoning, responsibility, collaboration with colleagues and superiors, attitude towards prisoners, and moral leadership. The latter (4 of the 70 items) are only for superiors. The response options were ‘totally disagree’, ‘disagree’, ‘neutral’, ‘agree’ and ‘totally agree’; or when asked about frequency ‘never’, ‘a few times per year’, ‘monthly’, ‘weekly’ and ‘daily’. In the post-measurement, 15 questions were added about the number of MCD sessions attended and how participants evaluated the MCD sessions.

Data analysis

The main analysis was performed on all respondents who completed either the pre-measurement and/or the post-measurement. Descriptive statistics were used for demographic characteristics and scores on all items. In an exploratory factor analysis (Principal Component Analysis with varimax rotation), we checked whether the 70 items formed separate clusters. As this was not the case, we continued further analyses on the individual item level.

To check whether the results on the 70 ordinal level items could be analysed as continuous variables, i.e., allowing multivariate analyses, we compared the P-values of the Chi-squared test and the independent sample t-test, between the pre- and post-measurement in both the control group and the intervention group. As these results were fairly similar, more advanced analyses were possible.

ANOVA tests were performed to compare the mean scores of the items on differences between a) the pre- and post-measurement within the control group, and within the intervention group, b) the control- and the intervention group at the pre-measurement, and c) the control- and intervention group at the post-measurement. In subgroup analyses, we examined whether certain professional disciplines showed larger or smaller changes between the pre- and post-measurement on specific items.

Furthermore, ANOVA tests were conducted to see whether the number of MCDs and the evaluation of these MCDs affected the impact of the intervention. In multivariate linear regression analyses, the effect of the intervention of MCD was adjusted for differences between the control- and intervention group in the various professional disciplines involved, having or not having contact with prisoners, sex, age, education level and duration of employment. We added a multi-level component to take into account that some of the participants completed both the pre- and post-measurement. Next, a multiple regression was conducted to check whether the closing of the prisons of Zwaag and Almere had an effect on the results.

Finally, we performed an extra analysis in the subgroup of participants who completed both a pre- and post-measurement, and whose scores could be compared using a coded link. We compared the impact of MCD on MCS in this linked file to the results of the main analysis. To this end, the same analyses as described above were performed.

Research ethics

The Institutional Review Board of Amsterdam UMC (location VUmc) waived the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO). The Dutch Custodial Institutions Agency (DCIA) of the Ministry of Justice and Security in the Netherlands gave permission. Involved researchers signed a DCIA confidentiality agreement to handle research data appropriately. Before filling in the survey, participants received information about the research project and confidentiality was emphasized. Participants gave informed consent, and agreed to voluntary participation, with the possibility to discontinue participation at any moment without specifying reasons.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Data was collected between October 2017 and September 2020: 459 participants completed the pre-measurement and the post-measurement was completed by 456 participants. In the pre-measurement, 45% of the participants were included in the intervention group (versus 55% in the control group), in the post-measurement 39% (versus 61%). Most participants were men and most were aged between 45 and 64 years. More about the characteristics of participants from the main analysis can be found in Table 1. The pre- and post-measurements could be linked for 163 participants (326 questionnaires out of the total of 915). The characteristics of these participants are presented in Appendix 2.

Main analysis: impact for all respondents

As the analyses of Chi square tests and ANOVA tests were comparable, and correction for co-variates did not change the main findings, we will focus on discussing the differences in percentages between the pre- and post-measurements of the intervention group. Where relevant, we will address changes in the control group. All pre- and post-measurement results in the intervention group and control group can be found in Appendix 3.

In the intervention group, significant progression on 7 out of 70 items was observed at post-measurement compared to the pre-measurement. This means participants scored higher on some elements of MCS after the MCDs than before the MCDs. Figure 1 shows plots of the items with a significant positive change.

The item ‘We are given tools to deal with moral dilemmas at work’ showed a strong significant change in the intervention group, from 25% of the participants (strongly) agreeing in the pre-measurement to 39% in the post-measurement, while in the control group only a quarter of the participants indicate agreeing (strongly) at post-measurement. The majority of participants in the intervention group (strongly) agreed with asking colleagues (84%) as well as superiors (91%) questions to understand why they do/did something in a particular way. For the item ‘In my work it is allowed to make mistakes’ we also saw a significant change in the control group.

We found significant changes in unexpected directions in two items in the intervention group, with no change in the control group (Table 2).

For the item ‘My work mostly consists of routine actions’ 25% of the intervention group indicated in the pre-measurement that they (strongly) agree, compared to 32% in the post-measurement. Initially, we expected that MCD allows participants to experience and become aware that there are always alternative options when making decisions about their actions. Seeing these results, it could also be the other way around: experiencing more deliberative freedom during the MCD sessions, perhaps they now experience their work even more as routine actions.

As to the item ‘Colleagues explaining to the team why they acted the way they did after a difficult situation’, about half of the intervention group (51%) indicated (strongly) agreeing at the pre-measurement compared to only 42% at the post-measurement. We expected the MCD sessions to contribute to more explaining behaviour among colleagues, yet perhaps, again, the respondents became aware that, in comparison with the MCD sessions, they do not actually explain that much.

So far, we have mentioned the items that showed a change. For some items we expected to find positive (significant) differences between the pre- and post-measurements of the intervention group, as they were thought to be more closely related to the properties of the MCD intervention (see Table 3). However, we did not find significant changes for these items in the intervention group, nor in the control group.

When we repeated this analysis for mean scores, we saw the same results. Also based on the linked pre- and post-measurements, the extra analysis differed only slightly from the main analysis, indicating that the results are robust.

Differences in impact between professional discipline

There were a number of clear differences between the general scores on elements of MCS between pre- and post-measurement and between the scores per discipline. We discuss interesting differences for the disciplines on items that did not show differences in the main analysis. For one item, ‘knowing the personal values and norms of my immediate colleagues’, we saw more positive progress in a specific discipline: ‘office staff re-integration services’ scored considerably higher in the post-measurement (87%) compared to the pre-measurement (71%). For the other professional disciplines this item remained more or less the same.

We also saw that, after attending the MCDs, healthcare professionals scored lower with regard to ‘wondering whether they’re doing the right thing during work’ and correctional officers scored lower on 'deviating from agreements and protocols when they feel it is right to do so'. ‘Office staff re-integration services’ indicate at post-measurement that there is less 'attention to why they make certain decisions in their team’ and that ‘during work, they as a team ask themselves whether they are doing the right thing’.

Differences in impact between the number of MCDs attended

Data on the number of MCDs attended by participants, and how they experienced and evaluated them, was available for the intervention group in the post-measurement. We divided the number of MCDs attended into 3 categories: 1–3, 4–6 and 7 + times participation in MCD sessions (Appendix 4). This subgroup analysis shows that on three items the group that participated 4 to 6 times (n = 50/156) in MCDs showed a larger difference between pre and post measurement than the group that participated in 1 to 3 MCDs. These items were: ‘How often do moments occur in your work in which you are uncertain of the right action to take?’, ‘I know the personal values and norms of my immediate colleagues’ and ‘At work we are given tools to deal with moral dilemmas’. However, this larger difference did not remain or increase with 7 + MCDs. The group that attended the most MCDs did not always show the largest difference on the items. Thus, attending more MCDs does not necessarily lead to a greater impact on MCS.

Differences in impact based on different evaluations of MCD

In the evaluations of MCD, 17% of the participants scored (very) negative and 43% scored (very) positive (Appendix 5).

In the scores for the MCS items, split according to the evaluation of MCD by prison staff (positive–negative), we found significant differences on 4 of the 70 items. Prison staff who evaluate MCD positively indicated more frequently that they ‘are given tools to deal with moral dilemmas at work’ and ‘as a team ask themselves whether they are doing the right thing during their work’. A possible explanation is that participants who evaluate MCD positively are more aware of the tools they are given at work, and they consider reflecting on the question whether they are doing the right thing more valuable. In addition, participants who evaluate MCD positively indicated less frequently that ‘their work consists mostly of routine actions’ and more often that ‘it is allowed to make mistakes in their work’.

Correction for other factors (multivariate regression analyses)

The multivariate linear regression analysis showed that other variables had little or no influence on the impact of MCD on MCS; the items that showed significant differences are the same as those in the main analyses.

Finally, an analysis was performed excluding the prisons of Almere and Zwaag. This analysis showed that the previously described differences sometimes increased or decreased on certain items, but there were no consistent changes in a particular direction.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the impact of a series of MCDs on elements of MCS for Dutch prison staff through a pre- and post-measurement questionnaire. This research is innovative in at least two ways. First, the concept of MCS is relatively unexplored and to date no validated questionnaire is available to measure impact on MCS. We therefore developed a questionnaire with several items based on an exploration of the concept of MCS from various literature sources. Second, ethics support in general, and MCD in particular, has not been offered and implemented in the involved Dutch prisons. Dutch prison staff is not used to specific methodologies for reflecting upon their moral challenges or dilemmas.

Most research on outcomes of MCD in general, not specifically for impact on MCS, has been conducted in healthcare settings, where ESS and MCD are offered and implemented on a regular basis (Gallagher 2006; Clark and Taxis 2003). In quantitative research in the healthcare context no positive effect of MCD was found on reduced moral distress (Kälvemark et al. 2007) or improved work climate (Forsgärde et al. 2000). Both studies indicate that it is, among other things, difficult to measure the effects of a complex intervention such as MCD with the existing research instruments (Svantesson et al. 2014). By contrast, analyses of various qualitative studies, also conducted in healthcare, have shown that MCD leads to positive results (Haan et al. 2018; Molewijk et al. 2008a; Hem et al. 2015). Because of the different contexts and cultures within Dutch healthcare and prisons, results of ethics support interventions in healthcare cannot be extrapolated to the prison setting.

The quantitative analyses of our impact study in the prison context of DCIA showed a positive development in some elements of MCS following the series of MCDs. The intervention group scored significantly higher on 7 items after participating in MCD. Most of the significant changes found were interpreted as being positive for MCS. There was a large number of items that had not (statistically significantly) changed at post-measurement. We initially had expected more impact after the intervention of MCD. We will mention some possible explanations for why items did not change.

First, in current literature, the concept of MCS is not yet clearly defined and instrumentalized. Therefore, this research has to show whether the used items “catch” the concept of MCS. Despite the existence of questionnaires that measure the outcomes of MCD, there was not yet a questionnaire that looks specifically at the impact on MCS. The innovative questionnaire developed for this study is not yet validated. Further investigation is needed in order to be able to effectively measure the impact of an ESS intervention.

Furthermore, it was the first time a series of MCDs took place at these prison locations. It was the first time, and therefore unusual for Dutch prison staff, that they looked at their own work in this way. For large parts of the staff (in particular security guards, correctional officers, office staff re-integration services and labour instructors) the work is characterized by routines, regulations and protocols, in addition to a clear hierarchy (Houwelingen 2015). On top of that, Dutch prison staff experienced high work pressure at the time of the study (FNV Overheid 2017). These organizational circumstances probably made achieving a positive impact on MCS particularly challenging.

Not finding quantitative changes does not necessarily mean that there are no positive changes in practice after MCDs. Many qualitative studies show positive impact of MCD (Janssens et al. 2015; Hem et al. 2018; Haan et al. 2018). Yet, quantitative research in the context of healthcare has yet to detect impact of MCD. More in general, international evaluation and impact research has shown that quantitative mapping of changes after the implementation of a complex intervention, such as MCD, can be difficult for various reasons (Schildmann et al. 2019; Svantesson et al. 2014).

The hoped for and/or expected outcome of MCD can also vary depending on the context, as demonstrated by the differences between the professional disciplines. Different outcomes of the subgroup analyses can be logically explained. The post-measurement of office staff re-integration services showed a more positive development on ‘knowing the personal values and norms of their immediate colleagues’. An explanation for this might be that office staff re-integration services usually work individually instead of in a team. Joint reflection during MCDs means more contact between this staff, which can help them get to know each other better, and gain more insight into each other's personal values and norms.

Only 34% (54/156) of the intervention group participants indicated participating in 7 or more MCDs in the post-measurement. A large proportion of the participants therefore took part in less than 7 MCDs. As researchers, we expected that a minimum of 7 to 10 MCDs would be required for a clear positive impact on MCS of prison staff. Contrary to expectations, we did not find a greater impact with an increasing number of MCDs. However, this may be explained by a lower-than-expected overall impact of MCD, making it difficult to find an effect in subgroups.

Also, the content of some items in the questionnaire were open to multiple interpretations. This should be improved in a new version of the questionnaire. For example, whether a change is positive or negative for MCS depends on the meaning of the item. It is, for example, possible that some participants view an item such as ‘In my work it is allowed to make mistakes’ as a negative statement (for example, because of the focus on safety in prison it is perceived as not being attentive or careful), which may make them more inclined to disagree with this statement. However, one could also interpret this positively: we are open to making mistakes and learn from them.

Prison staff who have not yet participated in MCDs may respond to items differently than after attending MCDs. Staff who participate in MCD can learn a lot from and score higher on elements of MCS. However, it is also possible that, because of what they learn in MCD, they become more aware that some items are more or barely present, or absent in practice, so they score lower in the post-measurement.

Finally, it was striking that some elements of MCS already scored relatively high in the control group and in the pre-measurement of the intervention group (Appendix 3), for example ‘I know the personal values and norms of my immediate colleagues' (69%) and ‘During work, I wonder whether I’m doing the right thing’. To measure progress on these items the scores after MCD then had to be even higher.

Strengths and limitations

For this study, a series of MCDs were organized, executed and examined in prison for the first time. It was also the first time that the impact of MCD was investigated on such a large scale. A strength of this study was that the intervention group included many different disciplines participating in MCD series.

Since this study was explorative, implementation of MCD in DCIA as well as investigation of the impact of MCD on MCS require further steps. After further development, it will be possible to gain more insight into the impact on the MCS of professionals.

The statistical analyses were performed on item level because exploratory factor analyses did not result in specific clusters of items. This may be an advantage because analyses on item level give us a clearer picture on the impact of MCD on elements of MCS, and on which particular elements.

Scope of further research

In daily practice in prisons, the (further) development of MCS of prison staff does not end. MCS is a continuous learning process. For that reason, one series of 10 MCDs per team, in which not all team members participated in all sessions, is probably not enough to improve MCS at the team level in an organization. In order to strengthen MCS among Dutch prison staff, an ongoing process is needed that stimulates joint moral reflection; during regular MCD sessions but also in regular work meetings. After all, moral issues will continue to arise within prisons. Therefore, structural and permanent attention, with the help of ESS and MCD, for staff’s moral awareness and for handling moral challenges in a constructive manner, remains necessary to further develop the MCS of individuals, teams and the organization as a whole.

In this context, it could be interesting to study whether the impact of MCDs is larger when staff are more familiar with the approach of MCDs, for example in teamwise reflection about morally challenging situations and sharing staff’s own (ethical) expertise. After all, following teams for a year and a half, with only 35% of the participants from the intervention group (post-measurement) participating in 7 or more MCDs, does not provide a full picture of the possible impact that MCD can have on MCS within DCIA.

The explorative MCS questionnaire should be shortened, further adapted and validated based on the many insights from this research. Validation of this questionnaire would help to make it more compact and reliable; for example, by examining how to include items that are less open to different interpretations. With a validated questionnaire, it may become possible to map the impact of ESS and other interventions on MCS more efficiently.

In this study we merely looked at the impact of MCD on the participants’ MCS and which elements of MCD affected the views and actions of the staff who took part in MCD. However, developing MCS should be part of a broader policy that fosters a moral climate of openness and transparency on several levels in the organization and in various ways (Hartman et al. 2020). In future research, we can look beyond just the staff, and also include organizational aspects and pre-conditions to promote a climate of joint moral reflection.

Conclusion

This unique and innovative research examined the impact of a series of MCDs on elements of the MCS of Dutch prison staff. A positive development was observed in some elements of MCS after participation in MCDs. However, the number of items that showed positive development was limited. We elaborated on possible reasons for this. The potential of ESS, and MCD in particular, for Dutch prisons has not yet been fully achieved. Regarding follow-up research into the impact of MCD on MCS, we advise shortening and validating the questionnaire to measure impact of future ESS on MCS. The (further) development of MCS of prison staff is not something that is finished at some point. It should be an integrated part of working in prisons. This study shows some first positive elements of MCD impact on MCS, which we believe justifies further investment in and investigation of the potential value of a structured moral reflection on the ongoing moral challenges in Dutch prisons.

Data Availability

The data, collected and analysed for this study is confidential but can be made available by the corresponding author after a reasonable request.

Notes

For DCIA we made a slight adjustment in this dilemma method. Together with the facilitators we decided to mainly focus on the formulation of a dilemma, instead of as well including a ‘moral question’.

References

Clark, Angela P., and J. Carole Taxis. 2003. Developing ethical competence in nursing personnel. Clinical Nurse Specialist 17 (5): 236–237.

Crigger, N., M. Fox, T. Rosell, and W. Rojjanasrirat. 2017. Moving it along: A study of healthcare professionals' experience with ethics consultations. Nursing Ethics 24 (3): 279–291.

DCIA. 2016. Vakmanschap en de vakmanschapsladder - Divisie GW/VB [craftmanship and its developmental steps - Division prisons and detention centres] [DCIA internal document]

FNV Overheid. 2017. Onderzoek werkdruk bij DJI - “Op te veel plekken te weinig ogen”.

Forsgärde, M., B. Westman, and L. Nygren. 2000. Ethical discussion groups as an intervention to improve the climate in interprofessional work with the elderly and disabled. Journal of Interprofessional Care 14 (4): 351–361.

Gallagher, Ann. 2006. The teaching of nursing ethics: Content and method. Promoting ethical competence. In: Essentials of teaching and learning in nursing ethics: perspectives and methods. ed. Anne Davis, Verena Tschudin, and Louise De Raeve. 223–239. London: Churchill Livingstone.

Haan, M.M., J.L. Van Gurp, S.M. Naber, and A.S. Groenewoud. 2018. Impact of moral case deliberation in healthcare settings: A literature review. BMC Medical Ethics 19 (1): 1–15.

Hartman, L., G. Inguaggiato, G. Widdershoven, A. Wensing-Kruger, and B. Molewijk. 2020. Theory and practice of integrative clinical ethics support: A joint experience within gender affirmative care. BMC Medical Ethics 21 (1): 1–13.

Hem, M.H., R. Pedersen, R. Norvoll, and B. Molewijk. 2015. Evaluating clinical ethics support in mental healthcare: A systematic literature review. Nursing Ethics 22 (4): 452–466.

Hem, M.H., B. Molewijk, E. Gjerberg, L. Lillemoen, and R. Pedersen. 2018. The significance of ethics reflection groups in mental health care: A focus group study among health care professionals. BMC Medical Ethics 19: 1–14.

Houwelingen, G., N. Hoogervorst, and M. van Dijke. 2015. Reflectie en actie. Een onderzoek naar moreel leeroverleg binnen Dienst Justitiële Instellingen (DJI). [Reflection and action. A study on moral learning consultation within DJI].

Janssens, R.M.J.P.A., E. van Zadelhoff, G. van Loo, G.A.M. Widdershoven, and A.C. Molewijk. 2015. Evaluation and perceived results of moral case deliberation: A mixed methods study. Nursing Ethics 22 (8): 870–880.

Kälvemark, S., B. Arnetz, M.G. Hansson, P. Westerholm, and A.T. Höglund. 2007. Developing ethical competence in health care organizations. Nursing Ethics 14 (6): 825–837.

Kowalski, M. 2020. Ethics on the radar: Exploring the relevance of ethics support in counterterrorism. Diss. Leiden University.

Molewijk, A. C., T. Abma, M. Stolper, and G. Widdershoven. 2008a. Teaching ethics in the clinic. The theory and practice of moral case deliberation. Journal of Medical Ethics, 34(2): 120–124.

Molewijk, B., E. van Zadelhoff, B. Lendemeijer, and G. Widdershoven. 2008b. Implementing moral case deliberation in Dutch health care; Improving moral competency of professionals and the quality of care. Bioethics Forum 1: 57–65.

Molewijk, B., M.H. Hem, and R. Pedersen. 2015. Dealing with ethical challenges: A focus group study with professionals in mental health care. BMC Medical Ethics 16 (1): 1–12.

Oprins, E., S. Dalenberg, M. 't Hart, M. de Graaff, and F. van Boxmeer. 2011. Measurement of moral competence in military operations. Conference paper, XI Biennial ERGOMAS conference, Amsterdam 201

Rasoal, D., A. Kihlgren, I. James, and M. Svantesson. 2016. What healthcare teams find ethically difficult: Captured in 70 moral case deliberations. Nursing Ethics 23 (8): 825–837.

Schaap, A. I., W.M.R. Ligtenberg, H.C.W. de Vet, A.C. Molewijk, and M.M. Stolper. 2022. Moral dilemmas of Dutch prison staff; A thematic overview from all professional disciplines. Corrections 1–18.

Schmalleger, F., and J. Smykla. 2014. Corrections in the 21st century.

Schippers, M. C., D. N. den Hartog, and P.L. Koopman. 2005. Reflexivity in teams: A measure and correlates. Applied Psychology: An International Review 56 (2): 189–211.

Schildmann, J., S. Nadolny, J. Haltaufderheide, M. Gysels, J. Vollmann, & C. Bausewein. 2019. Do we understand the intervention? What complex intervention research can teach us for the evaluation of clinical ethics support services (CESS). BMC Medical Ethics 20(1):1–12.

Shaw, D.M., T. Wangmo, and B.S. Elger. 2014. Conducting ethics research in prison: Why, who, and what? Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 11 (3): 275–278.

Stolper, M., B. Molewijk, G. Widdershoven. 2015. Learning by doing. Training health care professionals to become facilitator of moral case deliberation. HEC Forum 27(1): 47-59.

Stolper, M., B. Molewijk, and G. Widdershoven. 2016. Bioethics education in clinical settings: Theory and practice of the dilemma method of moral case deliberation. BMC Medical Ethics 17 (1): 1–10.

Svantesson, M., J. Karlsson, P. Boitte, J. Schildman, L. Dauwerse, G. Widdershoven, and B. Molewijk. 2014. Outcomes of moral case deliberation-the development of an evaluation instrument for clinical ethics support (the Euro-MCD). BMC Medical Ethics 15 (1): 1–12.

Van Baarle, E. 2018. Ethics education in the military. Fostering reflective practice and moral competence. Ministerie van Defensie - NLDA.

Weidema, F. 2014. Dialogue at work. Implementing moral case deliberation in a mental healthcare institution.

Weidema, F.C., A.C. Molewijk, F. Kamsteeg, and G.A.M. Widdershoven. 2013. Aims and harvest of moral case deliberation. Nursing Ethics 20 (6): 617–631.

Acknowledgements

W. Ligtenberg, M. Potma, N. Berkenbosch, S. Rooijakkers

This work was supported by the Dutch Custodial Institutions Agency of the Ministry of Justice and Security in the Netherlands.

This paper has not been published or accepted for publication. It is not under consideration by another journal. The authors declare they have no competing interests. All authors have substantially contributed to the article. All authors approved this version of the manuscript to be submitted.

Funding

This research was financed by the Dutch Custodial Institutions Agency of the Ministry of Justice and Security in the Netherlands.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was granted by Institutional Review board (IRB) of Amsterdam UMC, location VUmc. This study was considered not subject to the Medical Research Involving Human Subject Act (non-WMO). All used questionnaires stated voluntary participation, which could be discontinued at any moment without specific reasons, and emphasized the confidential use of the data.

Informed consent

All participants gave informed consent for the research.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix 1: Moral Case Deliberation: the dilemma method

Stolper M., (2016).

Appendix 1: Moral Case Deliberation: the dilemma method

-

1.

Introduction

Introducing moral case deliberation and its methodical approach, and discussing the objectives, expectations and confidentiality of the session.

-

2.

Presentation of the case

Providing a description of the case by the case owner, specifically at the moment the moral question is most prominent.

-

3.

Formulation of the dilemma and the underlying moral question

Identifying and formulating the two sides of the dilemma including the negative consequences, and the underlying moral questionFootnote 2 or moral theme.

-

4.

Empathising through elucidative questions

Asking elucidative questions in order to empathise with the situation and to gain a clear picture of the situation in order to be able to answer the moral dilemma question yourself.

-

5.

Perspectives, values and norms

Collecting the values and norms of relevant stakeholders involved and with respect to the dilemma.

-

6.

Alternatives

Free brainstorm focused on realistic and unrealistic options to deal with the dilemma.

-

7.

Individually argued consideration

Making individually a choice in the dilemma, how one would act in the specific situation of the case. Formulating the value that support one’s choice and the negative consequences of one’s action(s). Including formulating how to limit negative consequences. Finally, attention for ‘needs’ that help to accomplish the choice made.

-

8.

Dialogue about similarities and differences

Examining the similarities and differences in individual choices, argumentations and/or considerations.

-

9.

Conclusions and actions

Formulating conclusions with concrete actions or agreements regarding the discussed dilemma.

-

10.

Wrapping up and evaluation of lessons learned and the MCD session

Evaluating the MCD session, with the focus on the usefulness of MCD and what to organise differently next time (e.g. steps of the method, selected day and timeframe, groups dynamics, facilitator etc.).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huysentruyt, M., Schaap, A.I., Stolper, M.M. et al. Contribution of moral case deliberations to the Moral Craftmanship of prison staff: A quantitative analysis. International Journal of Ethics Education 8, 389–405 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40889-023-00165-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40889-023-00165-x