Abstract

Purpose

In the study of criminal careers, factors that predict continuity in offending are of importance to both theory and policy. One recently advanced hypothesis is Moffitt’s “economic maturity gap,” which argues that some adolescence-limited offenders may be mired in a poor economic situation. As only one study to date has examined this hypothesis, the current study seeks to extend this line of research by assessing the relationship of the economic maturity gap on later offending.

Methods

Using data from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development, three distinct operationalizations of the economic maturity gap are used to predict continued offending into mid-adulthood.

Results

Findings support the hypothesis that adolescence-limited males who experience this gap in late adolescence are more likely to continue offending into adulthood.

Conclusions

Experiencing poor economic circumstances helps to maintain offending into mid-adulthood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

While Moffitt [30] has discussed the possibility of another distinct offending group, childhood-limited offenders, the current study relies upon the original conceptualization of the taxonomy as this new group is of less direct relevance to our focus.

While our study also utilizes data from the same project, we extend Hagan’s research by considering multiple factors of fiscal well-being such as job quality and satisfaction. Further, we limit our analyses to a subsample of the males who are hypothesized to be on the adolescent-limited offending path.

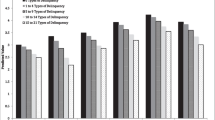

Based on Moffitt’s [28] original taxonomy, Craig and her colleagues [7] utilized Latent Class Growth Curve analysis to identify a three-class model. This form of modeling assumes a fixed slope and functional form for each trajectory class [32]. Various models were assessed and a quadratic form was selected due to overall model fit and parsimony. Additionally, as the posterior probabilities were greater than the threshold of 0.80, the models were successful in classifying a substantial majority of the individual trajectories into one of the three classes [33]. This method identified 7.2% of the sample as LCP offenders, 69.8% as abstainers, and 23% as AL offenders. While prior research by Nagin et al. [36] also used the CSDD to identify distinct offending trajectories, the Craig et al. [7] strategy sought to identify 3 offending groups while the Nagin et al. study furthered the work undertaken by Nagin and Land [34] who identified 4 groups (high-level chronic—13.4%, low-level chronic—9.9%, adolescent-limited—12.7%, and never convicted—64%).

We recognize that there is no precise, empirically based method for identifying AL offenders, and as such, we use this label for heuristic purposes only. We return to this point later in the manuscript.

The respondents were between the ages of 18 and 26 when asked these questions.

It could be argued that those males who were unemployed should be included in the low-status job category. However, as our index already includes a measure of unemployment, we did not want to double-count this particular category.

Readers may note that based on these coding decisions, it would be possible for a male that was incarcerated at age 18 to have a score of 0 or 1 on this index, based upon if he was in debt or not. It should be noted that only one respondent in our sample was incarcerated at this time.

Two additional operationalizations were also utilized in supplemental analyses. The first measure combined both essential and non-essential expenditure scales and then subtracted the respondents’ income from this sum. The second measure of the economic maturity gap represented our attempt to differentiate those experiencing the economic maturity gap from those that are not. We first assessed the distribution of the first measure in order to identify potential cut-points in the sample. Based on the distribution, we split the sample at approximately half. Those who scored 75 or more on the first measure were coded as 1, or experiencing the economic maturity gap to a greater degree than those who scored below this. Those who scored below a 75 were coded as 0. The results were substantially the same when compared to those presented in the manuscript and are available upon request.

The cut points for the essential/non-essential expenditures and income measures were original to the CSDD data.

We recognize the initial coding of these scales were not equal to one another pound-to-pound, an artifact of the original data collection. However, by recoding them, we retained the relative distribution and variability of the spending and income measures.

Note that this is similar to arrests in the USA.

It is also worth noting the offending scores for the full sample. Among the full CSDD, the adult offending score mean was 0.73 (standard deviation = 1.92) and ranged from 0 to 15.

Supplemental logistic regressions were also estimated using a dichotomous offending measure where 1 indicated that the individual had been convicted between the ages of 22 and 40. The results were substantially similar and are available upon request.

Supplemental chi-square and logistic regressions were also estimated using dichotomous measures of these main variables. The results indicated there was a significant difference in adult offending measures between those who experienced the economic maturity gap and those who did not.

References

Agnew, R. (1992). Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology, 30, 47–87.

Agnew, R. (2003). An integrated theory of the adolescent peak in offending. Youth Society, 34, 263–299.

Aguilar, B., Sroufe, L. A., Egeland, B., & Carlson, E. (2000). Distinguishing the early-onset/persistent and adolescence-onset antisocial behavior types: From birth to 16 years. Development and Psychopathology, 12, 109–132.

Amemiya, J., Vanderhei, S., & Monahan, K.C. (2016). Parsing apart the persisters: etiological mechanisms and criminal offense patterns of moderate- and high-level persistent offenders. Development and Psychopathology, 29(3), 819-835..

Barnes, J. C., & Beaver, K. M. (2010). An empirical examination of adolescence-limited offending: a direct test of Moffitt’s maturity gap thesis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38, 1176–1185.

Chiricos, T. G. (1987). Rates of crime and unemployment: an analysis of aggregate research evidence. Social Problems, 34, 187–212.

Craig, J. M., Morris, R. G., Piquero, A. R., & Farrington, D. P. (2015). Heavy drinking ensnares adolescents into crime in early adulthood. Journal of Criminal Justice, 43, 142–151.

Curtis, A., & Bandy, T. (2015). The quantum opportunities program: a randomized control evaluation. Washington, D.C.: The Eisenhower Foundation.

Dijkstra, J. K., Kretschmer, T., Pattiselanno, K., Franken, A., Harakeh, Z., Vollebergh, W., & Veenstra, R. (2015). Explaining adolescents’ delinquency and substance use: a test of the maturity gap: The SNARE study. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 52(5), 747–767.

Farrington, D. P. (1995). The Twelth Jack Tizard memorial lecture. The development of offending and antisocial behaviour from childhood: key findings from the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 360(6), 929–964.

Farrington, D. P. (2009). Integrated developmental and life-course theories of offending. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Farrington, D. P., Gallagher, B., Morley, L., St. Ledger, R. J., & West, D. J. (1986). Unemployment, school leaving, and crime. British Journal of Criminology, 26, 335–356.

Farrington, D. P., Coid, J. W., Harnett, L., Joliffe, D., Soteriou, N., Turner, R., & West, D. J. (2006). Criminal careers up to age 50 and life success up to age 48: new findings from the Cambridge study in delinquent development (Home Office research study no. 299). London: Home Office.

Farrington, D. P., Piquero, A. R., & Jennings, W. G. (2013). Offending from childhood to late middle age: recent results from the Cambridge study in delinquent development. New York: Springer.

Farrington, D. P., Gaffney, H., & Ttofi, M. M. (2017). Systematic reviews of explanatory risk factors for violence, offending, and delinquency. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 33, 24–36.

Galambos, N. L., Barker, E. T., & Tilton-Weaver, L. C. (2003). Who gets caught at maturity gap? A study of pseudomature, immature, and mature adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27, 253–263.

Hagan, J. (1993). The social embeddedness of crime and unemployment. Criminology, 31, 465–491.

Haynie, D. L. (2003). Contexts of risk? Explaining the link between girls’ pubertal development and their delinquency involvement. Social Forces, 82, 355–397.

Haynie, D. L., Weiss, H. E., & Piquero, A. R. (2008). Race, the economic maturity gap, and criminal offending in young adulthood. Justice Quarterly, 25(4), 595–622.

Higgins, G. E., Bush, M. D., Marcum, C. D., Ricketts, M. L., & Kirchner, E. E. (2010). Ensnared into crime: a preliminary test of Moffitt’s snares hypothesis in a national sample of African Americans. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice, 8(3), 181–200.

Hussong, A. M., Curran, P. J., Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., & Carrig, M. M. (2004). Substance abuse hinders desistance in young adults’ antisocial behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 16(4), 1029–1046.

Jennings, W. G., & Reingle, J. M. (2012). On the number and shape of developmental/life-course violence, aggression, and delinquency trajectories: a state-of-the-art review. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(6), 472–489.

Jennings, W. G., Rocque, M., Fox, B. H., Piquero, A. R., & Farrington, D. P. (2016). Can they recover? An assessment of adult adjustment problems among males in the abstainer, recovery, life-course persistent, and adolescence-limited pathways followed up to age 56 in the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Development and Psychopathology, 28, 537–549.

Keijsers, L., Branje, S., Hawk, S. T., Schwartz, S. J., Frijns, T., Koot, H. M., van Lier, P., & Meeus, W. (2012). Forbidden friends as forbidden fruit: parental supervision of friendships, contact with deviant peers, and adolescent delinquency. Child Development, 83(2), 651–666.

Kemple, J. J., & Scott-Clayton, J. (2004). Career academies: impacts on labor market outcomes and educational attainment. San Francisco: Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation.

Kemple, J. J., & Willner, C. J. (2008). Career academies: long-term impacts on labor market outcomes, educational attainment, and transitions to adulthood. San Francisco: Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation.

Loeber, R., & Farrington, D. P. (1998). Serious and violent juvenile offenders: risk factors and successful interventions. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100(4), 674–701.

Moffitt, T. E. (1994). Natural histories of delinquency. Cross-National Longitudinal Research on Human Development and Criminal Behavior, 76, 3–61.

Moffitt, T. E. (2006). A review of research on the taxonomy of life-course persistent versus adolescence-limited antisocial behavior. In F. T. Cullen, J. P. Wright, & K. R. Blevins (Eds.), Taking stock: the status of criminological theory (pp. 277–311). New Brunswick: Transaction.

Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Harrington, H., & Milne, B. J. (2002). Males on the life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways: follow-up at age 26 years. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 179–207.

Nagin, D. S. (2010). Group-based trajectory modeling: an overview. In A. R. Piquero & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative criminology (pp. 53–67). New York: Springer.

Nagin, D.S. (2005). Group-Based Modeling of Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nagin, D. S., & Land, K. C. (1993). Age, criminal careers, and population heterogeneity: Specification and estimation of a nonparametric, mixed Poisson model. Criminology, 31, 327–362.

Nagin, D., & Tremblay, R. E. (1999). Trajectories of boys’ physical aggression, opposition, and hyperactivity on the path to physically violent and nonviolent juvenile delinquency. Child Development, 70, 1181–1196.

Nagin, D. S., Farrington, D. P., & Moffitt, T. E. (1995). Life-course trajectories of different types of offenders. Criminology, 33, 111–140.

Piquero, A. R. (2008). Taking stock of developmental trajectories of criminal activity over the life course. In A. Liberman (Ed.), The long view of crime: a synthesis of longitudinal research (pp. 23–78). New York: Springer.

Piquero, A. R., & Brezina, T. (2001). Testing Moffitt’s account of adolescence-limited delinquency. Criminology, 39(2), 353–370.

Piquero, A. R., & Moffitt, T. E. (2005). Explaining the facts of crime: how the developmental taxonomy replies to Farrington’s invitation. In D. P. Farrington (Ed.), Integrated developmental & life-course theories of offending: advances in criminological theory (pp. 51–72). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Piquero, A. R., Farrington, D. P., & Blumstein, A. (2003). The criminal career paradigm. Crime and Justice, 30, 359–506.

Piquero, A. R., Farrington, D. P., & Blumstein, A. (2007). Key issues in criminal career research: new analysis of the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Piquero, A. R., Farrington, D. P., Nagin, D. S., & Moffitt, T. E. (2010). Trajectories of offending and their relation to life failure in late middle age: findings from the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 47, 151–173.

Piquero, A. R., Diamond, B., Jennings, W. G., & Reingle, J. M. (2013). Adolescence-limited offending. In C. L. Gibson & M. D. Krohn (Eds.), Handbook of life course criminology: emerging trends and directions for future research. New York: Springer.

Reyes, H. L. M., Foshee, V. A., Bauer, D. J., & Ennett, S. T. (2011). The role of heavy alcohol use in the developmental process of desistance in dating aggression during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(2), 239–250.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1990). Crime and deviance over the life course: the salience of adult social bonds. American Sociological Review, 55, 609–627.

Savage, J. (2009). The development of persistent criminality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stattin, H., Kerr, M., & Bergman, L. R. (2010). On the utility of Moffitt’s typology trajectories in long-term perspective. European Journal of Criminology, 7(6), 521–545.

West, D. J., & Farrington, D. P. (1977). Delinquent way of life: third report of the Cambridge study in delinquent development. New York City: Crane Russak & Co..

White, H. R., Bates, M. E., & Buyske, S. (2001). Adolescence-limited versus persistent delinquency: extending Moffitt’s hypothesis into adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(4), 600–609.

Zebrowitz, L. A., Andreoletti, C., Collins, M. A., Lee, S. Y., & Blumenthal, J. (1998). Bright, bad, babyfaced boys: appearance stereotypes do not always yield self-fulfilling prophecy effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1300–1320.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Craig, J.M., Piquero, A.R. & Farrington, D.P. The Economic Maturity Gap Encourages Continuity in Offending. J Dev Life Course Criminology 3, 380–396 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-017-0065-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-017-0065-6