Abstract

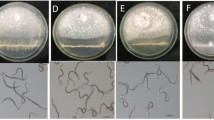

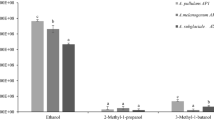

Meloidogyne species produce egg masses containing nutrients which may serve as feeding substrate for rhizospheric fungi. In the present work we isolated fungi form Meloidogyne paranaensis egg masses. Amongst the fungi isolated 67% belonged to the genus Fusarium and, within those, 52% of the isolates were of the species F. oxysporum. Isolates from F. oxysporum and F. solani significantly reduced M. incognita infectivity and reproduction in tomato when J2 were exposed to fungal volatiles, causing up to 100% immobility in in vitro tests. Water exposed to the volatile compounds produced by fungi and mixed to the J2 suspension caused toxicity in M. incognita J2 and reduced infectivity and reproduction of nematodes inoculated in tomato, when compared to the control. Using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), the volatile compounds produced by F. oxysporum and F. solani were identified and gathered in six main categories: esters, alcohols, phenols, aldehydes, carboxylic acids and sesquiterpenes, making up a total of 23 molecules. For the first time, 12 molecules from various chemical groups were identified in the water exposed to the volatiles from F. oxysporum and F. solani. A lower number of molecules were detected in the toxic water when compared with the vapors produced by fungi. Within these molecules, various have been already reported as having high nematicidal activity. Thus, F. oxysporum and F. solani fungi from M. paranaensis egg masses produce volatile compounds with antagonistic activity to M. incognita.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abdelnabby HM, Mohamed HA, Abo Aly HE (2011) Nematode-antagonistic compounds from certain bacterial species. Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control 21:209–217

Adams RP (2007) Identification of essential oil components by gas chromatography /mass spectrometry, 4th edn. Allured Publishing Corporation, Carol Stream

Anke H, Sterner O (1997) Nematicidal metabolites from higher fungi. Current Organic Chemistry 1:361–374

Arrebola E, Sivakumar D, Korsten L (2010) Effect of volatile compounds produced by Bacillus strains on postharvest decay in citrus. Biological Control 53:122–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2009.11.010

Atkins SD, Clark IM, Pande S, Hirsch PR, Kerry BR (2005) The use of real-time PCR and species-specific primers for the identification and monitoring of Paecilomyces lilacinus. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 51:257–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.femsec.2004.09.002

Barros AF, Campos VP, Silva JCP, Lopez LE, Silva AP, Pozza EA, Pedroso LA (2014) Tempo de exposição de juvenis de segundo estádio a voláteis emitidos por macerados de nim e de mostarda e biofumigação contra Meloidogyne incognita. Nematropica 44:190–199

Basseto MA, Bueno CJ, Augusto F, Pedroso MP, Furlan MF, Padovani CR, Furtado EL, Souza NL (2012) Solarização em microcosmo: efeito de materiais vegetais na sobrevivência de fitopatógenos de solo e na produção de voláteis. Summa Phytopathologica 38:123–130. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-54052012000200003

Campos VP, Villain L (2005) Nematode parasites of coffee and cocoa. In: Luc M, Sikora RA, Bridge J (eds) Plant parasitic nematodes in subtropical and tropical agriculture, 2nd Ed. CABI, Wallingford, pp 189–204. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851997278.0529

Campos VP, Pinho RSC, Freire ES (2010) Volatiles produced by interacting microorganisms potentially useful for the control of plant pathogens. Ciência e Agrotecnologia 34:525–535. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-70542010000300001

Carneiro RMDG, Carneiro RG, Abrantes IMO (1996) Meloidogyne paranaensis n.sp., a root-knot nematode parasitizing coffee in Brazil. Journal of Nematology 28:177–189

Castellani A (1939) The viability of some pathogenic fungi in sterile distilled water. Journal of Tropical Medicine and Higyene 42:225–226

Costa LSAS, Campos VP, Terra WC, Pfenning LH (2015) Microbiota from Meloidogyne exigua egg mass and evidence for the effect of volatiles on infective survival. Nematology 17:715–724. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685411-00002904

Dong JY, Zhang KQ, Zhao ZX, Bi TJ (2001) Current advances in nematicidal toxins from higher fungi. Chinese Journal of Biological Control 17:92–95

Eapen SJ, Beena B, Ramana KV (2005) Tropical soil microflora of spice-based cropping systems as potential antagonists of root-knot nematodes. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 88:218–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2005.01.011

Estupiñan-López L, Campos VP, Silva AP, Barros AF, Pedroso MP, Silva JCP, Terra WC (2017) Volatile organic compounds from cottonseed meal are toxic to Meloidogyne incognita. Tropical Plant Pathology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40858-017-0154-4

Fernando WGD, Ramarathnam R, Krishnamoorthy AK, Savchuk SC (2005) Identification and use of potential bacterial organic antifungal volatiles in biocontrol. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 37:955–964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.10.021

Fialho MB, Toffano L, Pedroso MP, Augusto F, Pascholati SF (2010) Volatile organic compounds produced by Saccharomyces cerevisiae inhibit the in vitro development of Guignardia citricarpa, the causal agent of citrus black spot. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 26:925–932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-009-0255-4

Fialho MB, Bessi R, Inomoto MM, Pascholati SF (2012) Nematicidal effect of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) on the plant-parasitic nematode Meloidogyne javanica. Summa Phytopathologica 38:152–154. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-54052012000200008

Freire ES, Campos VP, Pinho RSC, Oliveira DF, Faria MR, Pohlit AM, Noberto NP, Rezende EL, Pfenning LH, Silva JRC (2012) Volatile substances produced by Fusarium oxysporum from coffee rhizosphere and other microbes affect Meloidogyne incognita and Arthrobotrys conoides. Journal of Nematology 44:321–328

Griffits JS, Whitacre JL, Stevens DE, Aroian RV (2001) Bt toxin resistence from loss of a putative carbohydrate-modifying enzyme. Science 293:860–864. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1062441

Grimme E, Zidack NK, Sikora RA, Strobel GA, Jacobsen BJ (2007) Comparison of Muscodor albus volatiles with a biorational mixture for control of seedling diseases of sugar beet and root-knot nematode on tomato. Plant Disease 91:220–225. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-91-2-0220

Gu YQ, Mo MH, Zhou JP, Zou CS, Zhang KQ (2007) Evaluation and identification of potential organic nematicidal volatiles from soil bacteria. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 39:2567–2575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.05.011

Hallmann J, Sikora RA (1994) Occurrence of plant parasitic nematodes and nonpathogenic species of Fusarium in tomato plants in Kenya and their role as mutualistic synergists for biological control of root knot nematodes. International Journal of Pest Management 40:321–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/09670879409371907

Hussey RS, Barker KR (1973) A comparison of methods for collecting inocula of Meloidogyne spp. including a new technique. Plant Disease Reporter 57:1025–1028

Jardim IN, Oliveira DF, Silva GH, Campos VP, Souza PE (2017) (E)-cinnamaldehyde from the essential oil of Cinnamomum cassia controls Meloidogyne incognita in soybean plants. Journal of Pest Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-017-0850-3

Kerry BR (1984) Nematophagous fungi and the regulation of nematode population in soil. Helminthological Abstracts Serie B 53:1–14

Kerry BR, Evans K (1996) New strategies for the management of plant parasitic nematodes In: Hall R (Ed.) Principles and practice of managing soilborne plant pathogen. APS Press, St Paul. pp. 134–152

Kiewnick S, Sikora RA (2006) Biological control of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita by Paecilomyces lilacinus strain 251. Biological Control 38:179–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2005.12.006

Kok CJ, Papert A, Kok-A-Hin CH (2001) Microflora of Meloidogyne egg masses: species composition, population density and effect on the biocontrol agent Verticillium chlamydosporium (Goddard). Nematology 3:729–734. https://doi.org/10.1163/156854101753625236

Le TTH, Padgham JL, Hagemann MH, Sikora RA, Schouten A (2016) Developmental and behavioural effects of the endophytic Fusarium moniliforme Fe14 towards Meloidogyne graminicola in rice. Annals of Applied Biology 169:134–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/aab.12287

Lopes EA, Ferraz S, Freitas LG, Ferreira PA (2008) Controle de Meloidogyne javanica com diferentes quantidades de torta de nim (Azadirachta indica). Revista Trópica 2:17–21

Luo H, Li X, Li GH, Pan YB, Zhang KQ (2006) Acanthocytes of Stropharia rugosoannulata fuction as a nematode-attacking device. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 72:2982–2987. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.72.4.2982-2987.2006

Martinuz A, Schouten A, Sikora RA (2013) Post-infection development of Meloidogyne incognita on tomato treated with the endophytes Fusarium oxysporum strain Fo. 162 and Rhizobium etli strain G12. BioControl 58:95–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-012-9471-1

NIST (2017) NIST Chemistry Webook - National Institute of Standards and Technology. Available at: webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/. Accessed on 12 Feb 2017

Orion D, Kritzman G, Meyer SLF, Erbe EF, Chitwood DJ (2001) A role of the gelatinous matrix in the resistance of root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne spp.) eggs to microorganisms. Journal of Nematology 33:203–207

Riga E, Lacey LA, Guerra N (2008) Muscodor albus, a potential biocontrol agent against plant-parasitic nematodes of economically important vegetable crops in Washington state, USA. Biological Control 45:380–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2008.01.002

Rodriguez-Kabana R, Morgan-Jones G (1988) Potential for nematode control by mycofloras endemic in the tropics. Journal of Nematology 20:191–203

Salgado SML, Carneiro RMDG, Pinho RSC (2011) Aspectos técnicos dos nematóides parasitas do cafeeiro. Boletim Técnico 98. EPAMIG, Lavras

Silva JCP, Campos VP, Freire ES, Terra WC, Lopez EL (2017) Toxicity of ethanol solutions and vapours against Meloidogyne incognita. Nematology 19:271–280. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685411-00003046

Valente PAL, Augusto F (2000) Microextração por fase sólida. Química Nova, São Paulo

Xu YY, Lu H, Wang X, Zhang KQ, Li GH (2015) Effect of volatile organic compounds from bacteria on nematodes. Chemistry & Biodiversity 12:1415–1421. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbdv.201400342

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Sonia Maria de Lima Salgado (EPAMIG) for providing access to the experimental area in Piumhí (Minas Gerais). We acknowledge the financial aid granted by CAPES, CNPq and FAPEMIG. We also thank the mycology sector of the Dep. de Fitopatologia, Universidade Federal de Lavras, for the identification of the fungal isolates.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Section Editor: C. Marcelo Oliveira

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Estupiñan-López, L., Campos, V.P., da Silva Júnior, J.C. et al. Volatile compounds produced by Fusarium spp. isolated from Meloidogyne paranaensis egg masses and corticous root tissues from coffee crops are toxic to Meloidogyne incognita . Trop. plant pathol. 43, 183–193 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40858-017-0202-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40858-017-0202-0