Highlights

-

A solvent-free thermoplastic forming processing of graphene materials is invented by polymer intercalation from graphene oxide precursor.

-

The correlation between interlayer spacing and thermoplastic forming capability of polymer-intercalated graphene oxide solid is uncovered.

-

The multi-scale forming of graphene materials from Gaussian curved shapes to surface relief patterns with size precision down to 360 nm is realized.

Abstract

The processing capability is vital for the wide applications of materials to forge structures as-demand. Graphene-based macroscopic materials have shown excellent mechanical and functional properties. However, different from usual polymers and metals, graphene solids exhibit limited deformability and processibility for precise forming. Here, we present a precise thermoplastic forming of graphene materials by polymer intercalation from graphene oxide (GO) precursor. The intercalated polymer enables the thermoplasticity of GO solids by thermally activated motion of polymer chains. We detect a critical minimum containing of intercalated polymer that can expand the interlayer spacing exceeding 1.4 nm to activate thermoplasticity, which becomes the criteria for thermal plastic forming of GO solids. By thermoplastic forming, the flat GO-composite films are forged to Gaussian curved shapes and imprinted to have surface relief patterns with size precision down to 360 nm. The plastic-formed structures maintain the structural integration with outstanding electrical (3.07 × 105 S m−1) and thermal conductivity (745.65 W m−1 K−1) after removal of polymers. The thermoplastic strategy greatly extends the forming capability of GO materials and other layered materials and promises versatile structural designs for more broad applications.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Graphene macroscopic materials have exhibited attractive properties and promised wide applications in structural components, thermal management, sensors and electronic devices [1,2,3,4]. To satisfy the demands of more diverse applications of graphene, versatile forming methods are in need in order to design and fabricate precise shapes and structures. The available processing of graphene has relied on the solvent mediated processing methods, including dilute-solution assembly and solvent-plasticized forming. In the former method, dilute dispersions of graphene and its derivates are processed through solution casting [5,6,7], infiltration [8, 9], spray coating [10, 11] and wet-spinning [12,13,14], generating diverse forms, such as coatings, films and fibers. The dilute-solution processing has limited structural precision because of the severely volume shrinkage during solution evaporation. On the other hand, a hydroplastic forming method was newly developed to improve the structural precision by decreasing solvent content, introducing a near-solid processing state with solid content of 20–50% [15,16,17]. As to the extreme cases, solvent-free thermoplastic processing has been utilized to fabricate polymeric and metallic products in the industry [18,19,20,21]. For the environmental-friendly merit to avoid solvents and high processing precision for small volume change of thermoplastic process, it is an ultimate pursuit to develop the thermoplastic forming of graphene beyond dilute solution processing.

Thermoplastic processing of graphene is forbidden by its extremely high glass-transition point up to 6300 K, which exceeds the decomposition temperature of graphene (Td) [10]. To achieve the thermoplastic processing of graphene, an intuitive deduction is to blend graphene with the intrinsic thermoplastic polymer component. For this polymer-rich processing range, previous reports on graphene-polymer composites (usually less than 40% of graphene) seem to have minor guidance to the aimed thermoplastic processing of graphene [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. In these polymer-based materials, thermoplastic behavior of polymer matrix is invariably maintained [23, 29]. By contrast, in the graphene-rich range, the polymer exists in a confined state [30, 31]. The strongly confined polymers have been investigated to reveal rich and variable thermodynamic behaviors in many model systems, including absorbed surface, ultrathin self-standing films and trapped pores [32]. However, the thermal motion of confined polymers in the two-dimensional gallery and the consequent thermoplastic behavior of intercalated graphene oxide layered solid remains unclear.

Here, we demonstrate the solvent-free thermoplastic forming of graphene oxide solids by polymer intercalation, achieving the size precision from macro- to sub-micrometer. The thermal transition of intercalated polymer endows the bulk composite film with plasticity. We reveal that the glass-transition temperature (Tg) starts to appear and the rigid polymer-intercalated GO solid (Pi-GOS) is able to transform into plasticity when the interlayer spacing exceeds 1.4 nm, indicating a thermal forming criterion of containing above 45%. In the thermoplastic range, we forge flat films into stereoscopic structures with different Gaussian curvatures. We develop a thermoplastic imprinting method to design multiscale surface patterns and periodic arrays in a broad size precision from 360 nm to 200 μm. The thermoplastic imprinting allows the modulation of properties, including Janus material for actuators and responsive film surface with voltage-dependent wetting. Despite of the introduction of polymer plasticizer, the thermoplastic forming materials remain similar electrical (3.07 × 105 S m−1) and thermal conductivity (745.65 W m−1 K−1) as raw films after thermal annealing. The solvent-free thermoplastic forming strategy extends polymer-like forming techniques to graphene and other layered solids and meets complex structural designs in broader applications including humidity sensor, thermal management and functional surfaces.

2 Experimental Section

2.1 Materials

Aqueous graphene oxide dispersion (GO, 10 mg mL−1) was acquired from Hangzhou Gaoxi Technology Co. Ltd (www.gaoxitech.com). Poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA, 88% hydrolyzed, average MW 88000) was received from ACROS Organics Co. Ltd. Polyethylene glycol (PEG, 4000 MW) and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, 10000 MW) were purchased from Rhawn.

2.2 Preparation of Pi-GOS

PVA was dispersed into deionized water and the mixture was heated to 60 °C with magnetic stirring for 12 h to prepare solution with a concentration of 1%. Then, PVA solutions were mixed with GO dispersions which is diluted into 5 mg mL−1. With a fixed GO mass of 0.1 g, we prepared five solutions with different GO and PVA concentrations: (1) 80 wt.% GO with 20 wt.% PVA; (2) 67 wt.% GO with 33 wt.% PVA; (3) 50 wt.% GO with 50 wt.% PVA; (4) 33 wt.% GO with 67 wt.% PVA and (5) 20 wt.% GO with 80 wt.% PVA. Pi-GOSs were prepared by casting the GO/PVA complex solutions on a polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate and the drying process was maintained at the ambient temperature.

2.3 Forming Process

For macro- and micro-scale forming, the Pi-GOS was placed on or between the metallic moulds with designed structures, and then pressed at the forming temperature of 95 °C for varied time. After cooling to room temperature, the formed solid was easily separated from die. For the nanoimprinting process, we chose AAO membrane as template with diameter for 13 mm and hole size for 360 nm. After molding processing, the whole disc was reduced by hydriodic acid at 95 °C for 12 h and immersed in phosphoric acid solution (H3PO4, 50 wt.%) at 60 °C for 60 min to remove AAO film. To clean off the residual aqueous solution on the surface of disc, the demolded sample was washed by ethanol and n-hexane successively.

2.4 Characterization

The molding processing was carried out on a press (GT-7014-A50C). X-ray diffraction (XRD) profiles were collected on a X`Pert Pro (PANalytical) diffractometer using monochromatic Cu 17 Kα1 radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) at 40 kV. The glass-transition temperature was investigated by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) using a TA Q20 instrument. Mechanical tests were taken on TA Q800 at a loading rate of 1 mm min−1. The dynamic mechanical analysis was performed on a DMA 242E (NETZSCH Instruments). The measurements were carried out at a frequency of 1 Hz and a temperature ramp of 5 °C min−1. 3D-profile images were performed using an optical profilometer (Wyko NT9100). The indentation test was carried out by an Instron 2344 equipped with a load cell. The shells were placed on a plat and stiff base pressed by an indentor at the constant speed of 10 μm s−1. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images were taken on Hitachi S4800 and SU8010 field-emission SEM system. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of nanotubes were taken on a HT-7700 HR-TEM. Contact angle measurements were conducted by a video-based, contact angle measuring device (OCA 20).

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Thermoplastic Processing of Pi-GOS

The strong interlayer interactions of graphene oxide solid hamper the free motion of graphene oxide layers. Given this, thermoplastic polymer was intercalated between GO layers for the reduction of interlayer van der Waals force, as well as the introduction of thermal response [33,34,35,36]. The intercalated polymers should have appropriate glass-transition temperature (Tg < Td) and good affinity to GO, so the variety is constrained. To enable the thermoplastic forming of GO, we introduced polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) into GO solution and prepared homogenously mixed solid papers as raw material for thermoplastic forming (Figs. S1 and S2). The illustration of polymer intercalating process is shown in Fig. S3. The polymeric plasticizers can extend to other species with appropriate Tg, like Polyethylene glycol (PEG, Tg ~ 50 °C) and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, Tg ~ 130 °C) (Fig. S4). The film is thermally compressed against template and specific patterns with high precision are formed by the solids creeping into the hole of mold (Fig. 1a, b). When the Pi-GOS is heated to a target temperature (above Tg), the polymer segments in the interlamination begin able to move, thus endowing the plasticity of whole material. By thermoplastic processing on Pi-GOS, structures with large scale spanning from 4 to 390 nm were fabricated, including origami with stereo-structures, multiple patterns and nanopillar arrays.

3.2 Thermoplastic Behavior of Intercalated Polymer between GO Sheets

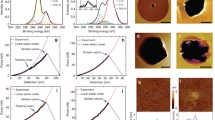

We investigated the thermodynamic behavior of intercalated polymer through XRD and dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA). The peak shift in XRD patterns indicates the expansion of interlayer spacing (d) with the increasing weight ratio of PVA to GO (α) and the interlayer spacing remains stable after long-term storage (Figs. 2a and S5). We detected that d and α follow a linear correlation as:

Meanwhile, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) obtained through XRD pattern increases with α, which means the decreasing orientation of GO sheets. According to Eq. (1), the thermal transition behavior can be directly connected with interlayer spacing. DSC tests revealed that Tg of Pi-GOS appears negative correlation with interlayer spacing and presents an increment of 12.3 °C. Meanwhile, the Tg disappears when d drops to 1.2 nm (Fig. 2b). The shift of Tg is caused by the increase in surface interactions between polymer and GO sheets, which suppresses the mobility of polymer chains [22, 37].

a Plots of the interlayer spacing and FWHM versus the weight ratio between PVA and GO. The insets presents the comparison between 1.12 nm (mPVA/mGO = 0.4) and 2.23 nm (mPVA/mGO = 2). b Glass-transition temperature measurement of Pi-GOS with different interlayer spacing. c Curves of storage modulus versus temperature with increasing interlayer spacing. The insets are the deformation abilities of forming structure versus d at 25 °C (blue) and 95 °C (red). d A plot of the ratio between storage modulus at 95 °C (E95) and that at 25 °C (E25) versus interlayer spacing of Pi-GOS

DMA tests revealed a similar transition in storage modulus of Pi-GOS as the interlayer spacing increases. For the Pi-GOS with d above 1.2 nm, the storage modulus manifests the second-order phase transition around the glass-transition temperature range as is stated above (Fig. 2c), compared with the stable and high storage modulus of neat GO solids [38]. The drastic decrease in storage modulus is attributed to activate softening of polymer matrix. In the Tfix region, PVA is in the glassy state and the whole film is brittle, which is failed to compression molding at any level of spacing. In the Tflow range, cooperative motions of polymer chains emerge above Tg, resulting in a rapid decrease in storage modulus [39, 40]. When the temperature continually increases, all PVA chains transform into the rubbery state and the storage modulus stays low and steady, therefore, this region is chosen for film forming. We set 95 °C as the processing temperature to avoid the reduction of GO and decomposition of polymer as well as ensure that the polymer chain is fully activated. Furthermore, the forming ability is strongly restrained while d was narrowed down to a certain value. Considering the relationship between the ratio of storage modulus at 95 (E95) to 25 (E25) °C and d, we have detected a negative correlation curve with changing fit slope (Fig. 2d). When the spacing of layers descends to 1.1 nm or below, the ratio of E95 to E25 is close to 1. This stable storage modulus region indicates an immobilization state of film. Along with the increasing d, the mobility of polymer segments is activated and the thermal plasticity of Pi-GOS emerges. According to these observations, we thus used Pi-GOS with a d of 1.4 nm (50% content of PVA) as raw material for following forming.

To evaluate the intrinsic deformability of thermoplastic forming, we investigated the mechanic behavior of Pi-GOS. Tensile test is used to analyze the brittle-to-ductile transition of Pi-GOS with different interlayer spacings (Figs. 3a and S6a, b). The stress–strain curve of Pi-GOS measured through DMA exhibits an obviously elastic (25 °C) to plastic transition (95 °C) with a 150% increase in breakage elongation. The transition can be rationalized as the expanding d weakens the van der Waals interaction between GO sheets by intercalated polymer, so that the chain segments of PVA are able to move above Tg [15, 34, 41]. Further, Pi-GOS exhibits typical elastic deformation regardless of d at room temperature (Fig. 3c). The mechanical properties remain stable after cooling from processing temperature (Fig. S6c). Given the same d (>1.2 nm), the failure strain is enhanced when temperature increasing to 95 °C, which implies a prominent assistance provided by the motion of polymer chains and the impact becomes prominent when the contents of PVA gradually increased. While d is narrowed down to 1.2 nm or below, for instance 0.9 nm, the elongation shows a diminution due to the frozen PVA chains. Meanwhile, the downward trend of Young’s modulus caused by both temperature and interlayer space can be interpreted as decreasing percentage of “bricks” (GO) and the motion of “mortar” (PVA segments). A microscopic contrast of activated sheet sliding under tension at room temperature and imprinting temperature is observed through fracture morphology analysis by SEM (Fig. 3b), which is consistent with the schematic of Fig. 3d. For delamination of GO sheets under 95 °C, the fracture exhibits a winding appearance and the average slippage width is about 2.4 μm, which signifies plastic deformation (Fig. 3b-(i)) [42]. By contrast, at room temperature (25 °C), the Pi-GOS presents a straight fracture across the paper and the average slippage width is about 0.5 μm, denoting a brittle fracture behavior without thermal transition (Fig. 3b-(ii)). These results reveal that the brittle-to-ductile transition of Pi-GOS only appears when the interlayer spacing and processing temperature both satisfy the conditions.

a Typical stress–strain curves of Pi-GOS (d = 3.1 nm) at 25 °C (blue) and 95 °C (red). b SEM images of transverse cross section morphology of Pi-GOS (d = 3.1 nm) after tensile breaking at 25 °C (top) and 95 °C (bottom). c Young’s modulus and elongation of Pi-GOS with different d-spacing at 25 °C (blue) and 95 °C (red). d Schematics of brittle tensile fracture of Pi-GOS below Tg and plastic tensile fracture above Tg

3.3 Multi-Scale Forming of Pi-GOS with Sub-Micro Precision

The materials with curved geometry usually possess enhanced mechanical stability compared to that of original flat sheets [43]. However, the inherent brittleness of graphene oxide solids confines the processing of forming GO composite film into stereo and curved shells [3]. In our work, the thermoplasticity of bulk Pi-GOS enables the fabrication of three-dimensional structures with the similar shaping techniques to polymer and metal products (Figs. 4a and S7). Starting from the flat papers, a spherical shell with positive Gaussian curvature and a cylinder with zero Gaussian curvature were shaped (Fig. 4b, c). The rigidity of curved shells was probed through indentation stiffness test carrying out by applying a point force in the convex surface center. The final force–displacement curves present the different bearing capacities between spherical and cylindrical shapes and are in good agreement with the finite element analysis (FEA) results (Fig. 4d). The stiffness (K) of the spherical shell, defined as the slope of the force–displacement curves, is higher than that of cylinder shell (Fig. S8), following the deduction as Kcylinder ~ Kspherical shell (t/R) 1/2 < < Kspherical shell, where t is the thickness and R is the principal radius of curvature (t/R < < 1) [43,44,45]. The simulation results display the deformations like a mirror-buckling along a circular rage in spherical shell and a smooth-edge dimple formed with two d-cones linked by an inverted ridge in cylindrical one [43, 46].

a Thermoplastic forming process of Pi-GOS from flat papers into stereostructures with positive curvatures. b FEA simulation results of indentation test for spherical and c cylindrical shells molded of Pi-GOS with same thickness (32 μm). d Force–displacement curves of spherical shell (blue square points) and cylindrical shell (red square points). Solid lines correspond to the fitting results

We used thermo-imprinting to fabricate micro-scale structures on the surface of Pi-GOS and the process can be double-imprinting. As shown in Fig. 5a, the composite solids can be patterned into micro-patterns by templates with corresponding size and even changeable through a programmable imprinting process. This result shows the potential of generating complex structures through one-sized template [47]. Along with the altering structure of hollow part of templates, a series of simple patterns were fabricated on the surface of composite film, including axial and central symmetry (Figs. 5b, S9 and S10). Meanwhile, complex patterns, such as the badge with varied line width, can also be generated with high fidelity. These flexible designs provide a new strategy to fabricate graphene-based solids as polymers and metals.

a Representation of multi-imprinting process from flat to micro-pattern stages. Scale bar, 50 μm. b Surface patterns on Pi-GOSs through micro imprinting: simple hexagon formed by triangles (left), embossment of the ZJU logo (right). Scale bars, 50 μm (left), 2 mm (right). c The curve of height-diameter ratio versus pressure and time. Dashed lines correspond to the fitting results and points represent experiment results (error bars are based on the standard error of the mean)

We further analyzed the influence factors in the height (H) of imprinting patterns. While the imprinted shape is settled as circle with constant diameter (D), the aspect ratio (H/D) denotes the shaping capability. For an immobile interlayer space (1.4 nm) of Pi-GOS, the imprinting pressure (\({\sigma }_{s})\) and time (t) follow a simplified classic Norton–Bailey’s creep power law [48]:

where Bi (i = 1, 2) are constants related to diameter, material properties and processing temperature (Fig. 5c). At a pressure of 188 MPa, the H/D is a function of imprinting time and the value of m is about 0.48. Meanwhile, the absolute value of n in the formula is approximately 0.96 at a fixed pressing time (5 min).

In addition to forming macro or micro-scale structures, nanorods with higher resolution down to 360 nm can also be generated by thermo-processing. We chose nanoporous anodic aluminum oxide (AAO) membrane with 360 nm apertures as template (Fig. 6a). After hot-pressing, the forming film was then chemical reduced and demolded. Because the forming precision is down to nanoscale, the formed solid becomes difficult to remove from the mold. The templates need to be dissolved and are therefore disposable, which can be developed in future works. Finally, the membrane with nanopillars on the surface was constructed. The nanorods are solid and perpendicular to the substratum which is formed with laterally arrayed lamella, as shown in the SEM images (Fig. 6b). The interior structure of the nanopillars is profiled in the model as shown in Fig. 6c. Under pressure at high temperature, GO sheets and PVA chains are squeezed into nanoholes and then form a hump wrapped by GO sheets when cooling down to room temperature. This solid structure indicates that the Pi-GOS fills the pores via capillary wetting because the interfacial energy between Pi-GOS and AAO template is comparatively weak [49]. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) inspection also exhibits sawback GO sheets laying along the white dotted line inside rod and the electron diffraction pattern of the pillar wall area confirms the existence of turbostratic graphene layers outside the rod, dictated as a broaden (002) diffraction ring (Fig. 6d) [50].

a Schematic diagram of thermal nanoimprinting process with through-hole AAO template. b SEM observations, c structural representation and d TEM images of the exterior and interior manufacture of nanorods. e SEM images of AAO template (top), imprinted Pi-rGOS nanopillars (middle) and heat reduced GLS nanopillars (bottom). f Raman spectra of Pi-rGOS and GLS. The insets are Raman mapping analysis of Pi-rGOS (up) and GLS (bottom) by considering the intensity ratio of D and G band

Figure 6e shows that the surface topography of imprinted polymer-intercalated reduced GO solid (Pi-rGOS) is well consistent with templates. We observed that the nanorods are consisted of reduced graphene oxide sheets, exhibiting the characteristic Raman peaks at ∼1348 and ∼1585 cm−1 (Figs. 6f and S11) [51]. The band at ~ 2922 cm−1 in the spectrum results from the strongest C-H stretching of PVA [52]. After annealing treated at 1400 °C to remove PVA, the surface topography of graphene layered solid (GLS) appears as shrunken rods and the ratio of D to G peak increased from 1.0–1.1 to 1.2–1.6 (Fig. 6f). The mappings of D-G peak ratio show a homogenous distribution of imprinting structure. And after further reduction at 3000 °C, this solid possesses similar structure and properties compared with raw GO film treated in the same fashion (GF) (Figs. S12 and S13).

3.4 Surface Properties of Nanopillar Array

The periodic structure on Pi-rGOS by nanoimprinting engineering greatly extends the surface properties of GO-based materials. The Pi-rGOS with one-side nanorods performs as Janus properties, which exhibits different water-contact angles of 81° on plain side and 56° on imprinted side (Fig. 7a). A straight film gradually bends when immersed into water and transforms into spiral shape quickly (a few seconds) (Figs. 7a and S14a). This Janus wettability promotes an implementation of water-induced actuator due to larger capillary forces [53] of nanorods, which is served as a driving force for complex deformation (Fig. S14b, c). The stable variation of ultimate curvature and length during 20 cycles of actuated deformation (Fig. 7b) demonstrates that the Pi-rGOS actuator possesses high reversibility and repeatability, which exhibits great potential in soft robotics and smart electronics.

a Schematic illustrations of Janus imprinted Pi-rGOS with different static contact angle on each side (top) and the reversible morphing behavior of Pi-rGOS (bottom). b Plots of length and curvature of Janus film versus cycle number during multiple wetting tests. c The change of apparent contact angle with a function of voltage when the GLS was settled as cathode (blue) and anode (red), respectively, and their corresponding Cassie and Semi-Cassie contact model

We also found the surface wettability of the GLS can be electrically adjustable by the effect of DC bias. To ensure the electrical conductivity, we chose heat-annealed GLS as a demo. A Pt wire was inserted into water droplet to establish electrical contact. Once the membrane is set as anode, the contact angle shows a sharp decrease from 123° to 75° as the droplet gradually sinking into membrane, which is corresponding to transformation from Cassie model (hydrophobic) to Semi-Cassie model (hydrophilic) (Fig. 7c). By contrast, the variation is weaker when a negative bias is applied to the GLS. Regardless of polarity, the wetting mechanism can be explained by the decline of solid–fluid interfacial tension. While the polarity-induced difference in wettability is resulted from the oxidation of a small minority of graphene on the surface [54, 55]. In addition, the droplet pumping speed shows a dependence on bias and the decrease in contact angle is much quickly at higher voltage, which is originated from the faster electrochemical oxidation speed (Fig. S15). Depending on the electrically adjustable wettability of GLS, we designed a sandwiched device for water transportation (Fig. S16). A water droplet (10 μL) was placed between two identical imprinted membranes and stayed on one side when no bias applied, which can be transferred to anode side via applying positive voltage of 10 V.

4 Conclusions

In this study, we developed a solvent-free thermoplastic forming of GO solid by polymer intercalation with high precision. We found that the thermoplasticity of Pi-GOS is fulfilled when the interlayer spacing exceeds 1.4 nm, which is the criterion for activation of intercalated polymer chain. Based on the thermoplasticity, we proposed the hot-shaping and thermal imprinting methods to process flat solids into rich structural forms with multiscale stereo attributes, ranging from macro to nanolevel (360 nm). Those complex deformations modify mechanical property and responsiveness of Pi-GOS and the thermoplastic forming materials remain good electrical as well as thermal conductivity after thermal annealing. The solvent-free thermoplastic forming approach provides new forming technology of GO materials and other layered materials, and further broadens the applications in versatile devices.

References

W. Dai, T. Ma, Q. Yan, J. Gao, X. Tan et al., Metal-level thermally conductive yet soft graphene thermal interface materials. ACS Nano 13(10), 11561–11571 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.9b05163

J. Shen, G.P. Liu, K. Huang, Z.Y. Chu, W.Q. Jin et al., Subnanometer two-dimensional graphene oxide channels for ultrafast gas sieving. ACS Nano 10(3), 3398–3409 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.5b07304

S.Y. Liu, M. Cerruti, F. Barthelat, Plastic forming of graphene oxide membranes into 3D structures. ACS Nano 14(11), 15936–15943 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.0c07344

B. Shen, W.T. Zhai, W.G. Zheng, Ultrathin flexible graphene film: an excellent thermal conducting material with efficient EMI shielding. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24(28), 4542–4548 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201400079

L. Huang, C. Li, W.J. Yuan, G.Q. Shi, Strong composite films with layered structures prepared by casting silk fibroin-graphene oxide hydrogels. Nanoscale 5(9), 3780–3786 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1039/C3NR00196B

G.I. Titelman, V. Gelman, S. Bron, R.L. Khalfin, Y. Cohe et al., Characteristics and microstructure of aqueous colloidal dispersions of graphite oxide. Carbon 43(3), 641–649 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2004.10.035

Y.H. Xiao, Z. Xu, Y.J. Liu, L. Peng, J.B. Xi et al., Sheet collapsing approach for rubber-like graphene papers. ACS Nano 11(8), 8092–8102 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.7b02915

Z. An, O.C. Compton, K.W. Putz, L.C. Brinson, S.T. Nguyen, Bio-inspired borate cross-linking in ultra-stiff graphene oxide thin films. Adv. Mater. 23(33), 3842–3846 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201101544

D.A. Dikin, S. Stankovich, E.J. Zimney, R.D. Piner, G.H.B. Dommett et al., Preparation and characterization of graphene oxide paper. Nature 448(7152), 457–460 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06016

G.Q. Xin, H.T. Sun, T. Hu, H.R. Fard, X. Sun et al., Large-area freestanding graphene paper for superior thermal management. Adv. Mater. 26(26), 4521–4526 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201400951

J. Zhong, W. Sun, Q.W. Wei, X.T. Qian, H.M. Cheng et al., Efficient and scalable synthesis of highly aligned and compact two-dimensional nanosheet films with record performances. Nat. Commun. 9(1), 3484 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05723-2

Z. Xu, C. Gao, Graphene chiral liquid crystals and macroscopic assembled fibres. Nat. Commun. 2, 571 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1583

Z. Liu, Z. Li, Z. Xu, Z.X. Xia, X.Z. Hu et al., Wet-spun continuous graphene films. Chem. Mater. 26(23), 6786–6795 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1021/cm5033089

Z. Li, Z. Xu, Y.J. Liu, R. Wang, C. Gao, Multifunctional non-woven fabrics of interfused graphene fibres. Nat. Commun. 7, 13684 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13684

P. Li, M.C. Yang, Y.J. Liu, H.S. Qin, J.R. Liu et al., Continuous crystalline graphene papers with gigapascal strength by intercalation modulated plasticization. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 2645 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16494-0

K. Pang, X. Song, Z. Xu, X.T. Liu, Y.J. Liu et al., Hydroplastic foaming of graphene aerogels and artificially intelligent tactile sensors. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd4045 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd4045

F. Guo, Y. Wang, Y.Q. Jiang, Z.S. Li, Z. Xu et al., Hydroplastic micromolding of 2D sheets. Adv. Mater. 33(25), 2008116 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202008116

A. Pucci, Smart and modern thermoplastic polymer materials. Polymers 10(11), 1211 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10111211

G.M. Scheutz, J.J. Lessard, M.B. Sims, B.S. Sumerlin, Adaptable crosslinks in polymeric materials: resolving the intersection of thermoplastics and thermosets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141(41), 16181–16196 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.9b07922

J.M. Garcia, M.L. Robertson, The future of plastics recycling. Science 358(6365), 870 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq0324

S.Y. Chou, P.R. Krauss, P.J. Renstrom, Nanoimprint lithography. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 14(6), 4129 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1116/1.588605

C.Q. Zhao, P.C. Zhang, J.J. Zhou, S.H. Qi, Y. Yamauchi et al., Layered nanocomposites by shear-flow-induced alignment of nanosheets. Nature 580(7802), 210–215 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2161-8

C.J. Huang, J.S. Peng, Y.R. Cheng, Q. Zhao, Y. Du et al., Ultratough nacre-inspired epoxy–graphene composites with shape memory properties. J. Mater. Chem. A 7(6), 2787–2794 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C8TA10725D

H. Jeon, Y. Kim, W.R. Yu, J.U. Lee, Exfoliated graphene/thermoplastic elastomer nanocomposites with improved wear properties for 3D printing. Compos. B Eng. 189, 107912 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.107912

K. Kalaitzidou, H. Fukushima, L.T. Drzal, Multifunctional polypropylene composites produced by incorporation of exfoliated graphite nanoplatelets. Carbon 45(7), 1446–1452 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2007.03.029

N. Saravanan, R. Rajasekar, S. Mahalakshmi, T.P. Sathishkumar, K.S.K. Sasikumar et al., Graphene and modified graphene-based polymer nanocomposites—a review. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 33(12), 1158–1170 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1177/0731684414524847

C. Vallés, A.M. Abdelkader, R.J. Young, I.A. Kinloch, The effect of flake diameter on the reinforcement of few-layer graphene–PMMA composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 111, 17–22 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2015.01.005

C. Vallés, A.M. Abdelkader, R.J. Younga, I.A. Kinlocha, Few layer graphene–polypropylene nanocomposites: the role of flake diameter. Faraday Discuss. 173, 379–390 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1039/C4FD00112E

J.J. Liang, Y. Huang, L. Zhang, Y. Wang, Y.F. Ma et al., Molecular-level dispersion of graphene into poly(vinyl alcohol) and effective reinforcement of their nanocomposites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 19(14), 2297–2302 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.200801776

R.L.G. Lecaros, G.E.J. Mendoza, W.S. Hung, Q.F. An, A.R. Caparanga et al., Tunable interlayer spacing of composite graphene oxide-framework membrane for acetic acid dehydration. Carbon 123, 660–667 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2017.08.019

Y.Q. Li, T. Yu, T.Y. Yang, L.X. Zheng, K. Liao, Bio-inspired nacre-like composite films based on graphene with superior mechanical, electrical, and biocompatible properties. Adv. Mater. 24(25), 3426–3431 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201200452

S. Napolitano, E. Glynos, N.B. Tito, Glass transition of polymers in bulk, confined geometries, and near interfaces. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80(3), 036602 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6633/aa5284

L.F. Wang, T.B. Ma, Y.Z. Hu, H. Wang, Atomic-scale friction in graphene oxide: an interfacial interaction perspective from first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 86(12), 125436 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.86.125436

S. Zheng, Q. Tu, J.J. Urban, S. Li, B. Mi, Swelling of graphene oxide membranes in aqueous solution: characterization of interlayer spacing and insight into water transport mechanisms. ACS Nano 11(6), 6440–6450 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.7b02999

K.W. Putz, O.C. Compton, M.J. Palmeri, S.T. Nguyen, L.C. Brinson, High-nanofiller-content graphene oxide-polymer nanocomposites via vacuum-assisted self-assembly. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20(19), 3322–3329 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201000723

C. Zhang, Y. Fujii, K. Tanaka, Effect of long range interactions on the glass transition temperature of thin polystyrene films. ACS Macro Lett. 1(11), 1317–1320 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1021/mz300391g

Y.X. Xu, W.J. Hong, H. Bai, C. Li, G.Q. Shi, Strong and ductile poly(vinyl alcohol)/graphene oxide composite films with a layered structure. Carbon 47(15), 3538–3543 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2009.08.022

X.D. Xia, J. Li, J.J. Zhang, G.J. Weng, Uncovering the glass-transition temperature and temperature-dependent storage modulus of graphene-polymer nanocomposites through irreversible thermodynamic processes. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 158, 103411 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijengsci.2020.103411

L.C. Tang, X. Wang, L.X. Gong, K. Peng, L. Zhao et al., Creep and recovery of polystyrene composites filled with graphene additives. Compos. Sci. Technol. 91, 63–70 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2013.11.028

F.Z. Wang, L.T. Drzal, Y. Qin, Z.X. Huang, Mechanical properties and thermal conductivity of graphene nanoplatelet/epoxy composites. J. Mater. Sci. 50(3), 1082–1093 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-014-8665-6

D.H. Kim, H.C. Lee, B.M. Kim, K.H. Kim, Estimation of die service life against plastic deformation and wear during hot forging processes. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 166(3), 372–380 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2004.07.103

S. Vinod, C.S. Tiwary, L.D. Machado, S. Ozden, J. Cho et al., Strain rate dependent shear plasticity in graphite oxide. Nano Lett. 16(2), 1127–1131 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b04346

A. Vaziri, L. Mahadevan, Localized and extended deformations of elastic shells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 7913–7918 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707364105

A. Lazarus, H.C.B. Florijn, P.M. Reis, Geometry-induced rigidity in nonspherical pressurized elastic shells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109(14), 144301 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.144301

D. Vella, A. Ajdari, A. Vaziri, A. Boudaoud, Indentation of ellipsoidal and cylindrical elastic shells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109(14), 144302 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.144302

A. Boudaoud, P. Patrício, Y. Couder, M.B. Amar, Dynamics of singularities in a constrained elastic plate. Nature 407(6805), 718–720 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/35037535

D.F. Huang, J.Y. Wu, C.J. Chen, X.X. Fu, A.H. Brozena et al., Precision imprinted nanostructural wood. Adv. Mater. 31(48), 1903270 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201903270

Z. Liu, One-step fabrication of crystalline metal nanostructures by direct nanoimprinting below melting temperatures. Nat. Commun. 8, 14910 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14910

T. Shimizu, Self-assembled nanomaterials II. Adv. Polym. Sci. 220, 123–187 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-85105-9

J.T. Wang, N. Salim, B. Fox, N. Stanford, Anisotropic compressive behaviour of turbostratic graphite in carbon fibre. Appl. Mater. Today 9, 196–203 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmt.2017.07.010

D. López-Díaz, M. López Holgado, J.L. García-Fierro, M.M. Velázquez, Evolution of the Raman spectrum with the chemical composition of graphene oxide. J. Phys. Chem. C 121(37), 20489–20497 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b06236

T.F. Cooney, L. Wang, S.K. Sharma, R.W. Gauldie, A.J. Montana, Raman spectral study of solid and dissolved poly(vinyl alcohol) and ethylene-vinyl alcohol copolymer. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 32(7), 1163–1174 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1002/polb.1994.090320704

Y. Kim, S. Lee, H.D. Cho, B. Park, D. Kim, Robust superhydrophilic/hydrophobic surface based on self-aggregated Al2O3 nanowires by single-step anodization and self-assembly method. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4(10), 5074–5078 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1021/am301411z

Y.H. Gao, G.J. Yin, S.W. Zhang, L. Wang, Q.J. Meng et al., Research progress in electrochemical preparation of graphene. J. Mater. Engin. 48(8), 84–100 (2020). https://doi.org/10.11868/j.issn.1001-4381.2019.000704

X.D. Zhao, H.M. Fan, J. Luo, J. Ding, X.Y. Liu et al., Electrically adjustable, super adhesive force of a superhydrophobic aligned MnO2 nanotube membrane. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21(1), 184–190 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201000603

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of staffs at State Key Laboratory of Chemical Engineering in Zhejiang University for performing SEM and DMA and the technical supports by the Core Facilities, State Key Laboratory of modern optical instruments, Zhejiang University. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51803177, 51973191, 51533008, and 51636002), National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2016YFA0200200), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2021M690134), Hundred Talents Program of Zhejiang University (188020*194231701/113), Key Research and Development Plan of Zhejiang Province (2018C01049), the National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (No. BX201700209), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2021FZZX001-17), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20210353) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 30920041106).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Guo, F., Pang, K. et al. Precise Thermoplastic Processing of Graphene Oxide Layered Solid by Polymer Intercalation. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 12 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-021-00755-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-021-00755-8