Highlights

-

An oxygen electrocatalyst consisting of Ni nanoparticles interpenetrated in porous NiO nanosheets was successfully synthesized.

-

The liquid Zn–air battery reveals a large open-circuit potential of 1.47 V, the maximum power density at 225 mW cm−2, and excellent device stability of over 120 h.

-

The flexible solid-like rechargeable Zn–air battery shows excellent stability (no evident weakening after 240 cycles) and bendability.

Abstract

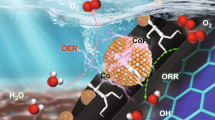

One approach to accelerate the stagnant kinetics of both the oxygen reduction and evolution reactions (ORR/OER) is to develop a rationally designed multiphase nanocomposite, where the functions arising from each of the constituent phases, their interfaces, and the overall structure are properly controlled. Herein, we successfully synthesized an oxygen electrocatalyst consisting of Ni nanoparticles purposely interpenetrated into mesoporous NiO nanosheets (porous Ni/NiO). Benefiting from the contributions of the Ni and NiO phases, the well-established pore channels for charge transport at the interface between the phases, and the enhanced conductivity due to oxygen-deficiency at the pore edges, the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets show a potential of 1.49 V (10 mA cm−2) for the OER and a half-wave potential of 0.76 V for the ORR, outperforming their noble metal counterparts. More significantly, a Zn–air battery employing the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets exhibits an initial charging–discharging voltage gap of 0.83 V (2 mA cm−2), specific capacity of 853 mAh g −1Zn at 20 mA cm−2, and long-time cycling stability (120 h). In addition, the porous Ni/NiO-based solid-like Zn–air battery shows excellent electrochemical performance and flexibility, illustrating its great potential as a next-generation rechargeable power source for flexible electronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

To meet the increasing demand for eco-friendly, renewable, and portable/mobile power sources, researchers have continued to study new energy conversion and storage systems [1,2,3,4,5]. Zn–air batteries have been widely studied owing to their high theoretical energy density, excellent safety, and eco-friendliness compared to other types of rechargeable batteries [6,7,8,9]. To improve the performance of Zn–air batteries, oxygen reduction and evolution reaction (ORR/OER) processes are required, where these reactions influence the charging–discharging progress [10,11,12]. Although Pt/Ir-based catalysts can perform well for either the ORR or OER, their application prospect is limited owing to the high cost and instability of these catalysts in commercial applications [13, 14]. Hence, there is an apparent urgency for exploring highly efficient non-noble metal electrocatalysts with rapid ORR/OER kinetics and superior overall performance.

Transition metals such as MnO2 [15], Co3O4 [16], and NiO [17] are considered as substitutes for noble metal-based electrocatalysts and have been in the spotlight as oxygen electrocatalysts for both the OER and ORR. For example, Zhuang and co-workers reported that the OER activity of transition metal oxides followed the order: NiOx > CoOx > FeOx > MnOx, suggesting that NiOx is an excellent candidate as an electrocatalyst [18]. However, most of these individual metallic oxides only afford a few of the desired ORR/OER performance parameters, rather than meeting the overall performance criteria. In addition, almost all of these oxides exhibit inherently poor electronic conductivity, which is a key problem that limits their electrocatalytic activity. Based on these understandings, considerable efforts have been devoted to developing solid-solution-type metal oxides, such as Fe-doped NiO and Ni-doped Co3O4 [19, 20], and nanocomposites of metal oxides/non-oxides, such as Fe–N–C nanosheet/NiO and NiO/Ni2P [21, 22]. A further approach is the use of conductive agents, such as carbon-based materials, which are incorporated to enhance the electron transfer to improve the OER activity [23, 24]. Nevertheless, the nanocomposite-type structure has to be controlled carefully to achieve synergy of the constituent components and properly control their interfaces. Otherwise, the overall performance will not be maximized, and the mechanical integrity will be poor, leading to peeling during long-term electrochemical cycling [25].

Indeed, the interface plays a critical role in enhancing the electrocatalytic performance of nanocomposite-type catalysts, where the heterojunction and fine-tuning of the interfacial electronic structure can be exploited. For example, tuning of the metal–semiconductor interface can effectively enhance the charge transport, as reported recently for graphene/Ni/MnO particles [25], Co/Ni3N nanowires [26], N-doped carbon/Co/CeO2 [27], and MoB/g-C3N4 nanosheets [28]. In electrocatalysts comprising Ni/NiO core@shell nanosheets, the metallic Ni core can accelerate electron transfer during the electrocatalysis process, while the amorphous NiO shell can lower the overpotential [21, 29, 30]. Gong and co-workers have proposed that the Ni/NiO interfaces are the active sites for HER catalysis in alkaline media [31]. More recently, a Ni–NiO heterostructure-based rechargeable Ni–Zn battery with an outstanding electrochemical performance was demonstrated [32]. Based on this background, a properly engineered Ni/NiO core@shell structure and the interfacial heterojunction between the two can lead to significantly improved ORR and OER performance. Herein, we synthesize a mesoporous Ni/NiO (porous Ni/NiO) nanosheet structure, where both of the constituent phases and their interfaces are purposely fine-tuned in the overall mesoporous structure, aiming at achieving synergistic effects among the components.

Herein, we report an efficient strategy for synthesizing a bifunctional electrocatalyst comprising porous Ni/NiO nanosheets, where the catalyst exhibits outstanding electrocatalytic stability with overpotential of 1.49 V (10 mA cm−2) and half-wave potential of 0.76 V in the OER and ORR, respectively. The porous Ni/NiO nanosheet-based Zn–air batteries show long-time cycling stability and high initial charging–discharging transfer efficiency (57.1%) compared with the congeners employing Pt/C-RuO2 [33, 34]. The solid-like batteries exhibit the desired mechanical flexibility and overall good electrochemical performance, revealing their potential applications in future flexible devices.

2 Experimental Section

2.1 Material Preparation

2.1.1 Synthesis of Ni/NiO Nanosheets

In a typical experiment, 0.005 mol NiCl2·6H2O, 0.1 mol NaOH, and 0.08 mol NaH2PO2·H2O were dissolved in 60 mL deionized (DI) water under vigorous stirring for 2 h. After that, the homogeneous miscible liquid was transferred to a 100-mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave, which was placed in an oven at 130 °C for 12 h. The resultant precursor was rinsed with DI water and ethanol several times. Finally, the dried precursor was annealed at 400 °C under argon atmosphere for 2 h.

2.1.2 Synthesis of Porous Ni/NiO Nanosheets

The as-prepared Ni/NiO nanosheets were post-treated with 1.0 M HCl for 24 h. The product was then separated by centrifuging, washed with sufficient deionized water, and dried.

2.1.3 Synthesis of NiO Nanosheets

For comparison, NiO nanosheets were prepared by omitting NaH2PO2·H2O from the above process.

2.2 Material Characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi S-4800) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Tecnai G2 F30, FEI) were employed to study the microstructure of the samples. An X-ray diffractometer (XRD; X’pert Pro Philips with Cu-Kα radiation) was used to identify the crystal structure and phases of the samples. The chemical states and bonding characteristics were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; Kratos AXIS Ultra) and Raman spectroscopy (Jobin–Yvon LabRam HR80). The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area and pore size were measured by using a Micrometrics ASAP 2020 V403 instrument. Fourier transform of the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra were collected at room temperature in the vicinity of the Ni K-edge at the X-ray absorption fine structure for catalysis (XAFCA) beamline of the Singapore Synchrotron Light Source (SSLS), Singapore. The energy was calibrated using a neodymium foil. The EXAFS data were analyzed by using WINXAS 3.1 code. The data were normalized and transformed from energy space to momentum (k) space, the background absorption was removed, and the \(\chi\)(k) function was extracted in the range of 1.5‒10.6 Å−1. Fourier transform of \(\chi\)(k) weighted by k3 (i.e., k3x(k) in R space) was performed using the Bessel function.

2.3 Electrochemical Measurements

Electrochemical measurements were conducted by using a three-electrode setup and a CHI 760E electrochemical workstation at room temperature (25 ± 0.5 °C). Ag/AgCl and a graphite rod or platinum foil were used as the reference electrode and counter electrode, respectively. The measured potentials (vs. Ag/AgCl) were converted to the RHE and iR corrected according to the Nernst equation (ERHE = EAg/AgCl + 0.197 + 0.059 pH). For the working electrode, 3 mg of the electrocatalyst was dispersed in 1470 μL of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and sonicated for 4 h to form the catalyst ink. Thereafter, the fresh catalyst ink (12.6 μL) was dropped onto a rotating disk working electrode (RDE) at a loading of 0.2 mg cm−2 and then dried at room temperature. For comparative purposes, commercially acquired Ir/C and Pt/C (20 wt%) were used as reference catalysts. All the ORR and OER properties were tested in 0.1 M KOH solution at room temperature.

2.4 Assembly of Aqueous Zn–Air Batteries

A liquid Zn–air battery was assembled using the home-made air cathode. The aforementioned electrocatalyst ink was dropped onto carbon fiber paper (CFP) at a loading of 2 mg cm−2 and dried at room temperature prior to use as the air cathode. A polished Zn plate was used as the anode, and 6 M KOH or 6 M KOH with 0.2 M zinc acetate was used as the electrolyte for the primary and rechargeable Zn–air batteries, respectively. The battery performance was evaluated using a potentiostat (CHI 760E, CH Instrument Co.) and LAND testing system. For comparison, the performance of the Zn–air battery with 20 wt% Pt/C was also tested under the same conditions.

2.5 Solid-like Zn–Air Batteries

A flexible solid-like Zn–air battery was assembled by employing the porous Ni/NiO on carbon fiber paper (CFP) as the air cathode, a zinc anode, and a polymeric hydrogel electrolyte. The polymeric hydrogel electrolyte was prepared as follows: One gram of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) powder was dissolved in 10 mL of H2O at 95 °C under magnetic stirring for 2 h. When the mixture was transformed into a transparent gel, 1 mL of 18 M KOH was added and stirred until the gel became homogeneous. The helical-structured Zn foil was then inserted into a glass bottle with sufficient PVA glue, and the contents of the glass bottle were then frozen to the solid state. The porous Ni/NiO/CFP was tightly attached to the newly assembled helical structure of Zn/PVA with parafilm.

2.6 Calculation Details

The computational code of the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) was used for the spin-polarized DFT calculations. The standard generalized-gradient approximation (GGA) was adopted for the exchange–correlation potential. The energy cutoff of the plane waves used for expanding the electronic wavefunctions was 400 eV. A Monkhorst–Pack k-point mesh of 4 × 4 × 4 was used for the geometry optimization and electronic property calculations. The atomic positions and cell parameters were optimized until the residual force was below 0.01 eV Å−1. Because of the strong on-site Coulomb repulsion (strong correlation) between the d electrons of the Ni atoms, standard density functional theory (DFT) cannot adequately describe the physical properties of NiO. Based on previous recommendations, we used the DFT + U method with U = 6.3 eV and J = 1 eV to describe the electronic properties of NiO correctly, where U and J indicate the on-site screened Coulomb energy and exchange interactions, respectively [35]. To calculate the point O defects within the periodic boundary conditions, we adopted a Ni32O32 supercell that is compatible with the type-II antiferromagnetic structure of NiO. In type-II antiferromagnetic ordering, the spin moments of Ni atoms in the same (111) plane are ferromagnetically arranged, and the orientations of the spin moments between adjacent planes are alternately arranged [36]. Ni/NiO heterojunctions were fabricated according to the finite strain theory; the best matching interface follows the orientation relationship of Ni (111)//NiO (111) with an interfacial strain of 2.6%.

3 Results and Discussion

The porous Ni/NiO nanosheets were obtained by partially etching the exposed Ni nanoparticles in the Ni/NiO nanosheets. The present aim is to develop efficient bifunctional OER/ORR electrocatalysts by exploiting the synergistic effects of both components, their interfaces, as well as the controlled porous structure (a schematic depiction is presented in Fig. 1a). TEM images of the three products (NiO, Ni/NiO, and porous Ni/NiO nanosheets) are shown in Figs. S1 and 1b, c, respectively. Post-etching treatment with HCl induced the formation of numerous mesopores in the Ni/NiO nanocomposite. Therefore, in the nanosheets, the Ni nanoparticles were implanted in the mesoporous NiO network. To further reveal the crystal structure of both Ni and NiO, high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) studies were conducted, which confirmed the presence of the remaining Ni and mesoporous NiO matrix, as shown in Fig. 1d. There was a clear contrast between the two crystalline phases, as shown in Fig. 1e, where lattice fringes with interplanar distances of ≈ 2.42 and ≈ 2.04 Å were observed for the NiO (111) and Ni (111) facets, respectively, further confirming the development of the Ni/NiO phase in the nanosheets [37, 38]. The XRD patterns of the three products shown in Figs. 1f and S2 indicate that the diffraction peaks are consistent with cubic Ni (JCPDS No. 87-0712) and cubic NiO (JCPDS No. 78-0423). Notably, after the acid etching treatment, the intensity of the Ni diffraction peaks for the mesoporous Ni/NiO decreased considerably. The combined XRD and TEM results confirm partial etching of the Ni nanoparticles by HCl, resulting in the formation of mesopores in the nanosheets. The porous nature of the nanosheets observed by TEM is also supported by the BET surface area measurement, where the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms of the three samples are shown in Fig. 1g. The data show that porous Ni/NiO possesses the typical features of mesoporous materials, with a measured surface area of 186.8 m2 g−1 and total pore volume of 0.412 cm3 g−1, which are much higher than those of Ni/NiO (106.3 m2 g−1, 0.266 cm3 g−1) and NiO (64.1 m2 g−1, 0.167 cm3 g−1). Moreover, the average size of these mesopores was estimated to be 4 nm for the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets (Fig. S3), which is consistent with the HRTEM results presented above.

a Schematic diagram showing the formation of porous Ni/NiO nanosheets, with excellent OER and ORR performance, and the use of the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets as a highly efficient air electrode for Zn–air batteries. TEM images of b Ni/NiO, c porous Ni/NiO nanosheets, d and e high-resolution TEM images of porous Ni/NiO nanosheets. f XRD patterns and g BET data for NiO, Ni/NiO, and porous Ni/NiO nanosheets. h XANES and i EXAFS spectra for NiO, Ni/NiO, porous Ni/NiO nanosheets, and Ni reference

To verify the local atomic structures of NiO, Ni/NiO, and the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets, the synchrotron X-ray absorption near edge spectra (XANES) were acquired. Figure 1h presents the normalized XANES data for both Ni/NiO and porous Ni/NiO, as compared to those of Ni foil and NiO. The absorption edge of Ni/NiO and porous Ni/NiO was intermediate between the Ni and NiO edges, indicating the mixed oxidation states of Ni (Ni0 and Ni2+) [39]. Notably, the absorption edge of the Ni/NiO nanosheets was similar to that of Ni, while that of the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets shifted toward that of NiO owing to the decreased Ni content. This observation was further confirmed by Fourier transform of the extended EXAFS κ3χ data for the Ni K-edge and the corresponding oscillations (Figs. 1i, S4). Compared to the signal for the Ni/NiO nanosheets, the intensity of the signal of the Ni–Ni bond (2.1 Å) indicates a decrease in the content of metallic Ni, while the scattering caused by the Ni–O (1.6 Å) and Ni–Ni (2.6 Å) bonds corresponds to an increase in the NiO content for the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets [40, 41]. The XANES and EXAFS data therefore confirm the Ni–O coordination structure and a decrease in the content of metallic Ni in porous Ni/NiO, resulting from acid etching.

XPS analysis was further carried out, and the Ni 2p spectra of these three samples are shown in Fig. S5. The fitting results for the Ni 2p3/2 peaks for each sample are presented in Fig. 2a to reveal their valence states. The peaks at 853.61, 855.60, and 860.71 eV correspond to the Ni–O bond, surface states, and satellite peak of common NiO, respectively [42, 43]. A new peak also appeared at 852.52 eV for both Ni/NiO and porous Ni/NiO, which is related to metallic Ni [44]. Notably, the signal of the Ni–O bond shifted (~ 0.45 eV) toward lower energy for Ni/NiO and porous Ni/NiO, compared to that of pure NiO. This is attributed to the interface and the effect of the O-deficiencies [26, 27]. The O 1s spectra (Fig. 2b; Table S1) of all three samples were well fitted to three peaks, where the common two peaks at 529.14 and 532.64 eV reveal the presence of the Ni–O bond and surface adsorbed oxygen, while the peak at 530.96 eV reveals the existence of O-deficiencies in these samples [45]. The percentage of O-deficiencies was highest (36.1%) for the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets, revealing that the acid treatment led to more defects, which may have a positive effect on the electrocatalytic properties [46]. The DFT data provide further evidence to support this claim. As shown in Fig. 2c, pure NiO exhibits semiconductor characteristics with a band gap of 3.10 eV, whereas the band gap of NiO with O-deficiencies was much narrower (0.65 eV), which may contribute to the high conductivity measured for the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets and therefore promote rapid charge transfer during the electrocatalytic process. The increased conductivity of NiO with O-deficiencies was also confirmed by the partial charge density results shown in Fig. 2d. Moreover, Fig. 2e shows the optimized atomic structure of the interface formed between the Ni(111) slab and NiO (111) with terminal Ni, where the charge density difference illustrates the accumulation of electrons at the interface and transfer from NiO to Ni. In the successfully formed porous Ni/NiO nanosheets, the electronic conductivity is effectively improved by the Ni core and O-deficiencies in the nanosheets. The large surface area and mesoporous structure may further increase the number of active sites, and therefore contribute to the highly enhanced electrocatalytic activity for the both OER and ORR, as discussed later.

a High-resolution Ni 2p and b O 2p XPS spectra for NiO, Ni/NiO, and porous Ni/NiO nanosheets. c Calculated DOS results for NiO with and without O-deficiencies. d Calculated partial charge density of NiO with and without O-deficiencies (the isosurface value is 0.001 e/bohr3). e Structure of the interface formed between Ni (111) and Ni-terminated NiO (111) slabs and the corresponding calculated charge density difference, where yellow and blue represent electron accumulation

Firstly, we examined the electrochemical activity of porous Ni/NiO for the OER, in comparison with that of NiO and the Ni/NiO nanosheets; the experiments were performed in 0.1 M KOH solution at a scan rate of 2 mV s−1. All of the potentials were referred to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) and were iR corrected. As shown in Figs. 3a, b, and S6, the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets exhibited excellent OER activity with the smallest overpotential of 1.49 V and a Tafel slope of 62 mV dec−1, compared with corresponding values of 1.53 V and 71 mV dec−1 for the Ni/NiO nanosheets and 1.69 V and 178 mV dec−1 for the NiO nanosheets, respectively. Notably, the measured overpotential of 1.49 V is smaller than that of Ir/C (1.53 V), indicating that the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets are an outstanding alternative to commercial Ir/C. The electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS), electrochemically active surface area (ECSA), and turnover frequency (TOF) were measured to gain insight into the OER reaction kinetics and effective active sites of the samples. The Nyquist plots shown in Fig. 3c indicate that porous Ni/NiO exhibited the lowest charge transfer resistance (Rct) of 46 Ω, where the measured Rct values were 63 Ω for Ni/NiO and 118 Ω for NiO, suggesting higher conductivity and faster electron transfer for the porous Ni/NiO catalyst during the OER process. The ECSA represented by the double-layer capacitance (Cdl) shown in Figs. 3d and S7 was 26 mF cm−2 for the porous Ni/NiO, which was larger than that of Ni/NiO (20 mF cm−2) and twofold higher than that of NiO nanosheets (12 mF cm−2), revealing the largest exposed active sites for porous Ni/NiO [47]. The TOF values measured at a potential of 1.5 V were 0.31 (NiO), 0.52 (Ni/NiO), and 2.15 (porous Ni/NiO) O2/s, as shown in Fig. 3e, demonstrating that the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets possess more active sites [48]. Stability is also an important parameter in the development of the electrocatalysts. As shown in Fig. 3f, the LSV curve of the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets after 10,000 potential cycles almost overlapped with the initial curve, confirming the outstanding stability of this catalyst against degradation in the accelerated OER process.

Rotating disk electrode (RDE) measurements were further employed to evaluate the ORR activity of the catalysts in O2-saturated 0.1 M KOH solution at a rotating speed of 1600 rpm. From Figs. 4a and S8, S9, the onset potential of the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets (defined by the tangent line where the current density increases rapidly and intersects with the horizontal line) was 0.87 V (~ 0.90 V for Pt/C), with a half-wave potential (E1/2) of 0.75 V (~ 0.79 V for Pt/C), limiting current density (jL) of 4.9 mA cm−2 (~ 5.0 mA cm−2 for Pt/C) (0.2 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE)), and kinetic current (jk) of 18 mA cm‒2 (~ 19 mA cm−2 for Pt/C) (0.6 V versus RHE), revealing the outstanding ORR performance of the Ni/NiO nanosheets. The number of electrons transferred per O2 (n), calculated from the Koutecky–Levich (K–L) plots, was 3.81 for the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets (inset of Figs. 4b, S10), suggesting that the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets favor a nearly four-electron pathway at a relatively low overpotential than other catalysts [49]. The ORR path of the catalysts was further verified by rotating ring-disk electrode measurements (RRDE), and the results are shown in Fig. 4c. The calculated n was also above 3.81 (Fig. 4d), and the yield of HO2− was below 7.5% (Fig. 4e) for the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets in the voltage region of 0.2–0.7 V, where the values are superior to those of Ni/NiO (n: 3.29 and HO2−: 36.4%) and NiO (n: 2.98 and HO2−: 50.2%). These values are very close to those of the Pt/C catalyst (n: 3.86 and HO2−: 6.3%), clearly demonstrating that the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets can efficiently induce the generation of oxygen at a relatively low overpotential. In general, the overall oxygen electrocatalytic activity and reversibility is estimated from the difference for the OER and ORR (E = Ej=10 − E1/2), where a lower E value is correlated with better bifunctional activity [50]. Figure 4f shows that the E value of 0.75 V for the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets is smaller than those reported for NiO-based or Ni-based bifunctional catalysts (Table S2), further revealing that the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets are an efficient bifunctional OER/ORR electrocatalyst. More importantly, the electrocatalytic stability of the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets for both the ORR and OER was evaluated. The i–t data in Fig. S11 show 97% and 94% retention for the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets after 15 h for the OER and ORR, which indicates that the Ni/NiO nanosheets are more stable than the Ir/C and Pt/C catalysts, respectively. The XRD, XPS, and TEM data shown in Figs. S12 and S13 indicate that the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets show outstanding stability.

a ORR curves for Pt/C, NiO, Ni/NiO, and porous Ni/NiO electrocatalysts. b ORR curves for porous Ni/NiO measured at different speeds; K–L plots obtained at different potentials are shown in the inset. c Disk and ring currents on RRDE with a ring potential of 1.5 V (vs. RHE). d Calculated n at different potentials, and e peroxide percentage for Pt/C, NiO, Ni/NiO, and porous Ni/NiO catalysts. f ORR and OER bifunctional activity of catalysts in this work compared with representative electrocatalysts in references (ΔE represents the typical difference values)

The remarkable bifunctional electrocatalytic activity of the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets may be attributed to the synergistic effects among the metallic Ni core, O-deficiencies in NiO, the interface between Ni and NiO, and the mesoporous structure. Firstly, the metallic Ni nanoparticles and the O-deficiencies in NiO play an important role in improving charge transport in the OER/ORR processes. Secondly, the conductive electrons can be easily transferred between the two phases owing to electron accumulation at the interface, which enhances the OER/ORR activity of the catalyst [51]. Finally, the mesoporous structure increases the number of exposed active sites, leading to higher electrochemical activity. Given the superior bifunctional activity of the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets discussed above, we assembled a rechargeable Zn–air battery to demonstrate the applicability of the nanosheets in energy storage and transformation. The diagram of the Zn–air battery presented in the inset of Fig. 5a shows three components: the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets as the air cathode, Zn plate as the anode, and 6.0 M KOH + 0.2 M zinc acetate as the electrolyte. The open-circuit potential (OCP) of the porous Ni/NiO nanosheet-based Zn–air battery shown in Fig. 5a is 1.47 V, which is comparable to that of the Pt/C-based battery with an OCP of 1.48 V. This is indeed larger than the values of 1.38 V for NiO and 1.43 V for Ni/NiO (Fig. S14). As shown in Figs. 5b and S15, a maximum power density of 225 mW cm−2 was obtained for the porous Ni/NiO nanosheets-based Zn–air battery, whereas that for the Pt/C-based battery was only 185 mW cm−2; the value for the Ni/NiO nanosheets is also larger than that of other recently reported systems (Table S3). To confirm its stability, we cycled the air cathode at 2 mA cm−2, where the duration of each cycle was 10 min. As shown in Fig. 5c, d, the porous Ni/NiO-based Zn–air battery had a long cycle life over 720 cycles (about 540 cycles for the Ni/NiO-based battery as shown in Fig. S16), where the voltaic efficiency decreased from 58.3% (the difference in the charging–discharging potential was 0.83 V at the first cycle) to 51.2% (the difference in the charging–discharging potential was 0.98 V at the 720th cycle). The results presented in Fig. 5e indicate that the Zn–air battery exhibited better discharging stability with stable performance as the current density was increased over the range of 1 to 22 mA cm−2. The specific capacity of the porous Ni/NiO-based Zn–air battery was 853 mAh g −1Zn with respect to the consumption of Zn, measured at 20 mA cm−2, as shown in Fig. S17, which is much larger than that of 20 wt% Pt/C + IrO2 (479 mAh g −1Zn ) [52]. Importantly, as shown in Figs. 5f and S18, two such Zn–air batteries in series could power an air fan and light-emitting diodes, revealing the potential of the Ni/NiO nanosheets for practical applications.

a, b Open-circuit potential, discharge curves, and power density curves for Pt/C, NiO, Ni/NiO, and porous Ni/NiO. Inset shows schematic diagram for solution Zn–air battery. c, d Long-term discharge–charge cycling performance at 2 mA cm−2 for porous Ni/NiO-based battery. e Discharge curves of porous Ni/NiO-based battery at different current densities. f Air fan powered by two porous Ni/NiO-based Zn–air batteries in series. g, h Long-term discharge–charge cycling performance for solid-like Zn–air battery at 5 mA cm−2, and i performance of porous Ni/NiO-based battery under bending at different angles at 2-h intervals

Moreover, we assembled a flexible solid-like Zn–air battery, where porous Ni/NiO was used as the air cathode, a zinc sheet was used as the anode, and polymeric hydrogel was used as the electrolyte. As shown in Fig. 5g, h, this solid-like Zn–air battery exhibited a long cycle life of over 240 cycles with a small decrease in the voltaic efficiency from 53.89% (the difference in the charging–discharging potential was 0.90 V at the first cycle) to 52.12% (the difference in the charging–discharging potential was 0.87 V at the 240th cycle). The OCP of this battery was 1.38 V, and two of these batteries in series could power a blue LED (~ 3 V), as shown in the inset of Figs. 5g and S19. Further, as shown in Fig. S19b–d, the solid-like Zn–air battery showed no major performance decay upon bending and exhibited cycling stability at different bending angles when measured at 2-h intervals (Fig. 5i), implying its potential applicability in future flexible electronics and wearable devices.

4 Conclusions

We developed a highly efficient electrocatalyst based on mesoporous Ni/NiO nanosheets, which were synthesized by a scalable process of hydrothermal growth and post-acid etching. The oxygen electrocatalyst is designed to consist of Ni nanoparticles purposely interpenetrated into mesoporous NiO nanosheets (porous Ni/NiO), with well-established pore channels for charge transport at the interface between the nanosheets, oxygen deficiencies at the pore edges (giving rise to enhanced electrical conductivity), and an overall mesoporous structure, leading to a higher surface area and therefore effective exposure of the active sites. Accordingly, the nanosheets show outstanding electrochemical performance and catalytic activity for both the ORR and OER. The application potential was demonstrated in air cathodes for rechargeable and flexible Zn–air batteries. The successful development of the mesoporous Ni/NiO nanosheets provides a new pathway for achieving non-noble metal-based bifunctional oxygen catalysts and air cathodes for Zn–air batteries.

References

M.A. Green, S.P. Bremner, Energy conversion approaches and materials for high-efficiency photovoltaics. Nat. Mater. 16(1), 23–34 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4676

N. Kittner, F. Lill, D.M. Kammen, Energy storage deployment and innovation for the clean energy transition. Nat. Energy 2(9), 17125 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2017.125

B. Hua, M. Li, W. Pang, W. Tang, S. Zhao et al., Activating p-blocking centers in perovskite for efficient water splitting. Chem 4(12), 2902–2916 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chempr.2018.09.012

J. Zhang, X. Bai, T. Wang, W. Xiao, P. Xi, J. Wang, Bimetallic nickel cobalt sulfide as efficient electrocatalyst for Zn–air battery and water splitting. Nano-Micro Lett. 11(1), 2 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-018-0232-2

W. Xu, Y. Wang, Recent progress on zinc-ion rechargeable batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 11(1), 90 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-019-0322-9

G. Fu, Z. Cui, Y. Chen, L. Xu, Y. Tang, J.B. Goodenough, Hierarchically mesoporous nickel–iron nitride as a cost efficient and highly durable electrocatalyst for Zn–air battery. Nano Energy 39, 77–85 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2017.06.029

J. Fu, F.M. Hassan, J. Li, D.U. Lee, A.R. Ghannoum, G. Lui, M.A. Hoque, Z. Chen, Flexible rechargeable zinc–air batteries through morphological emulation of human hair array. Adv. Mater. 28(30), 6421–6428 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201600762

W. Wan, X. Liu, H. Li, X. Peng, D. Xi, J. Luo, 3D carbon framework-supported CoNi nanoparticles as bifunctional oxygen electrocatalyst for rechargeable Zn–air batteries. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 240, 193–200 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.08.081

D. Yang, L. Zhang, X. Yan, X. Yao, Recent progress in oxygen electrocatalysts for Zinc–air batteries. Small Methods 1(12), 1700209 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/smtd.201700209

F. Meng, H. Zhong, D. Bao, J. Yan, X. Zhang, In situ coupling of strung Co4N and intertwined N–C fibers toward free-standing bifunctional cathode for robust, efficient, and flexible Zn–air batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138(32), 10226–10231 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.6b05046

Y. Cheng, S. Dou, J.P. Veder, S. Wang, M. Saunders, S.P. Jiang, Efficient and durable bifunctional oxygen catalysts based on NiFeO@MnOx core-shell structures for rechargeable Zn–air batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9(9), 8121–8133 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b16180

H. Li, W. Wan, X. Liu, H. Liu, S. Shen, F. Iv, J. Luo, Poplar–catkin–derived N, P co-doped carbon microtubes as efficient oxygen electrocatalysts for Zn–air batteries. ChemElectroChem 5(7), 1113–1119 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/celc.201701224

Q. Shao, J. Liu, Q. Wu, Q. Li, H.G. Wang, Y. Li, D. Qian, In situ coupling strategy for anchoring monodisperse Co9S8 nanoparticles on S and N dual-doped graphene as a bifunctional electrocatalyst for rechargeable Zn–air battery. Nano-Micro Lett. 11(1), 4 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-018-0231-3

Z. Qian, Y. Chen, Z. Tang, Z. Liu, X. Wang, Y. Tian, W. Gao, Hollow nanocages of NixCo1−xSe for efficient zinc–air batteries and overall water splitting. Nano-Micro Lett. 11(1), 28 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-019-0258-0

F. Cheng, T. Zhang, Y. Zhang, J. Du, X. Han, J. Chen, Enhancing electrocatalytic oxygen reduction on MnO2 with vacancies. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52(9), 2474–2477 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201208582

X. Chen, C. Zhong, B. Liu, Z. Liu, X. Bi et al., Atomic layer Co3O4 nanosheets: the key to knittable Zn–air batteries. Small 14(43), 1702987 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201702987

P.T. Babar, A.C. Lokhande, M.G. Gang, B.S. Pawar, S.M. Pawar, J.H. Kim, Thermally oxidized porous NiO as an efficient oxygen evolution reaction (OER) electrocatalyst for electrochemical water splitting application. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 60, 493–497 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2017.11.037

L. Zhuang, L. Ge, Y. Yang, M. Li, Y. Jia, X. Yao, Z. Zhu, Ultrathin iron–cobalt oxide nanosheets with abundant oxygen vacancies for the oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 29(17), 1606793 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201606793

K. Fominykh, P. Chernev, I. Zaharieva, J. Sicklinger, G. Stefanic et al., Iron-doped nickel oxide nanocrystals as highly efficient electrocatalysts for alkaline water splitting. ACS Nano 9(5), 5180–5188 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.5b00520

X. Zou, J. Su, R. Silva, A. Goswami, B.R. Sathe, T. Asefa, Efficient oxygen evolution reaction catalyzed by low-density Ni-doped Co3O4 nanomaterials derived from metal-embedded graphitic C3N4. Chem. Commun. 49(68), 7522–7524 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1039/c3cc42891e

J. Wang, K. Li, H. Zhong, D. Xu, Z. Wang, Z. Jiang, Z. Wu, X. Zhang, Synergistic effect between metal–nitrogen–carbon sheets and NiO nanoparticles for enhanced electrochemical water oxidation performance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54(36), 10530–10534 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201504358

H. Zhang, Y. Wang, D. Wang, Y. Li, X. Liu et al., Homologous NiO//Ni2P nanoarrays grown on nickel foams: a well matched electrode pair with high stability in overall water splitting. Nanoscale 9(13), 4409–4418 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/C6NR07953A

D.H. Guo, R. Shibuya, C. Akiba, S. Saji, T. Kondo, J. Nakamura, Active sites of nitrogen-doped carbon materials for oxygen reduction reaction clarified using model catalysts. Science 351(6271), 361–365 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad0832

H. Zhang, Y. Wang, D. Wang, Y. Li, X. Liu et al., Hydrothermal transformation of dried grass into graphitic carbon-based high performance electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction reaction. Small 10(16), 3371–3378 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201400781

G. Fu, X. Yan, Y. Chen, L. Xu, D. Sun, J.M. Lee, Y. Tang, Boosting bifunctional oxygen electrocatalysis with 3D graphene aerogel-supported Ni/MnO particles. Adv. Mater. 30(5), 1704609 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201704609

C. Zhu, A.L. Wang, W. Xiao, D. Chao, X. Zhang et al., In situ grown epitaxial heterojunction exhibits high-performance electrocatalytic water splitting. Adv. Mater. 30(13), e1705516 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201705516

L. Lv, D. Zha, Y. Ruan, Z. Li, X. Ao et al., A universal method to engineer metal oxide–metal–carbon interface for highly efficient oxygen reduction. ACS Nano 12(3), 3042–3051 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.8b01056

Z. Zhuang, Y. Li, Z. Li, F. Lv, Z. Lang et al., MoB/g-C3N4 interface materials as a Schottky catalyst to boost hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57(2), 496–500 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201708748

E. Navarro-Flores, Z. Chong, S. Omanovic, Characterization of Ni, NiMo, NiW and NiFe electroactive coatings as electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution in an acidic medium. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 226(2), 179–197 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2004.10.029

D.S. Hall, C. Bock, B.R. MacDougall, The electrochemistry of metallic nickel: oxides, hydroxides, hydrides and alkaline hydrogen evolution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 160(3), F235–F243 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1149/2.026303jes

M. Gong, W. Zhou, M.C. Tsai, J. Zhou, M. Guan et al., Nanoscale nickel oxide/nickel heterostructures for active hydrogen evolution electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 5, 4695–4700 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5695

Y. Zeng, Y. Meng, Z. Lai, X. Zhang, M. Yu, P. Fang, M. Wu, Y. Tong, X. Lu, An ultrastable and high-performance flexible fiber-shaped Ni–Zn battery based on a Ni–NiO heterostructured nanosheet cathode. Adv. Mater. 29(44), 1702698 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201702698

W. Niu, S. Pakhira, K. Marcus, Z. Li, J.L. Mendoza-Cortes, Y. Yang, Apically dominant mechanism for improving catalytic activities of N-doped carbon nanotube arrays in rechargeable zinc–air battery. Adv. Energy Mater. 8(20), 1800480 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.20180048

Y. Li, C. Zhong, J. Liu, X. Zeng, S. Qu, X. Han, Y. Deng, W. Hu, J. Lu, Atomically thin mesoporous Co3O4 layers strongly coupled with N-rGO nanosheets as high-performance bifunctional catalysts for 1D knittable zinc–air batteries. Adv. Mater. 30(4), 1703657 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201703657

A. Rohrbach, J. Hafner, G. Kresse, Molecular adsorption on the surface of strongly correlated transition-metal oxides: a case study for CO/NiO(100). Phys. Rev. B 69(7), 075413 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.69.075413

S. Park, H.S. Ahn, C.K. Lee, H. Kim, H. Jin, H.S. Lee, S. Seo, J. Yu, S. Han, Interaction and ordering of vacancy defects in NiO. Phys. Rev. B 77(13), 134103 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.77.134103

L. Qiao, X. Wang, L. Qiao, X. Sun, X. Li, Y. Zheng, D. He, Single electrospun porous NiO–ZnO hybrid nanofibers as anode materials for advanced lithium-ion batteries. Nanoscale 5(7), 3037–3042 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1039/c3nr34103h

V.A. Bharathan, R. Jain, C.S. Gopinath, C.P. Vinod, Diverse reactivity trends of Ni surfaces in Au@Ni core–shell nanoparticles probed by near ambient pressure (NAP) XPS. Catal. Sci. Technol. 7(19), 4489–4498 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/C7CY01070B

L. Del Bianco, F. Boscherini, M. Tamisari, F. Spizzo, M. Vittori Antisari, E. Piscopiello, Exchange bias and interface structure in the Ni/NiO nanogranular system. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 41(13), 134008 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/41/13/134008

L. Del Bianco, F. Boscherini, A.L. Fiorini, M. Tamisari, F. Spizzo, M.V. Antisari, E. Piscopiello, Exchange bias and structural disorder in the nanogranular Ni∕NiO system produced by ball milling and hydrogen reduction. Phys. Rev. B 77(9), 094408 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.77.094408

M. Patange, S. Biswas, A.K. Yadav, S.N. Jha, D. Bhattacharyya, Morphology controlled synthesis of monodispersed graphitic carbon coated core/shell structured Ni/NiO nanoparticles with enhanced magnetoresistance. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17(48), 32398–32412 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5CP05830A

Uhlenbrockt, C. Scharfschwerdtt, M. Neumannt, G. Illing, H.J. Freund, The influence of defects on the Ni 2p and O 1s XPS of NiO. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 4, 7973–7978 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/4/40/009

M.A. Peck, M.A. Langell, Comparison of nanoscaled and bulk NiO structural and environmental characteristics by XRD, XAFS, and XPS. Chem. Mater. 24(23), 4483–4490 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1021/cm300739y

J. Masa, I. Sinev, H. Mistry, E. Ventosa, M. de la Mata et al., Ultrathin high surface area nickel boride (NixB) nanosheets as highly efficient electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution. Adv. Energy Mater. 7(17), 1700381 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201700381

D.Q. Gao, G.J. Yang, J.Y. Li, J. Zhang, J.L. Zhang, D.S. Xue, Room-temperature ferromagnetism of flowerlike CuO nanostructures. J. Phys. Chem. C 114(43), 18347–18351 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1021/jp106015t

H. Xu, Z.X. Shi, Y.X. Tong, G.R. Li, Porous microrod arrays constructed by carbon-confined NiCo@NiCoO2 core@shell nanoparticles as efficient electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution. Adv. Mater. 30(21), 1705442 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201705442

K. Fan, H. Chen, Y. Ji, H. Huang, P.M. Claesson et al., Nickel–vanadium monolayer double hydroxide for efficient electrochemical water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 7, 11981 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11981

X. Liu, W. Xi, C. Li, X. Li, J. Shi et al., Nanoporous Zn-doped Co3O4 sheets with single-unit-cell-wide lateral surfaces for efficient oxygen evolution and water splitting. Nano Energy 44, 371–377 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2017.12.016

H. Yin, C. Zhang, F. Liu, Y. Hou, Hybrid of iron nitride and nitrogen-doped graphene aerogel as synergistic catalyst for oxygen reduction reaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24(20), 2930–2937 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201303902

M. Zhang, Q. Dai, H. Zheng, M. Chen, L. Dai, Novel MOF-derived Co@N-C bifunctional catalysts for highly efficient Zn–air batteries and water splitting. Adv. Mater. 30(10), 1705431 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201705431

X. Liu, W. Liu, M. Ko, M. Park, M.G. Kim et al., Metal (Ni, Co)-metal oxides/graphene nanocomposites as multifunctional electrocatalysts. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25(36), 5799–5808 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201502217

B. Chen, X. He, F. Yin, H. Wang, D.-J. Liu, R. Shi, J. Chen, H. Yin, MO-Co@N-doped carbon (M = Zn or Co): vital roles of inactive Zn and highly efficient activity toward oxygen reduction/evolution reactions for rechargeable Zn–air battery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27(37), 1700795 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201700795

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 11474137, 11674143) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. Lzujbky-2019-cd02). John Wang and team thank for the support of MOE (MOE2016-T2-2-138) for research conducted at the National University of Singapore.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, P., Ran, J., Xia, B. et al. Bifunctional Oxygen Electrocatalyst of Mesoporous Ni/NiO Nanosheets for Flexible Rechargeable Zn–Air Batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 12, 68 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-0406-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-0406-6