-

The Bi2O3 nanoplates homogeneously decorated free-standing exfoliated graphene (Bi2O3/FEG) was prepared by a facile electrochemical deposition method.

-

The Bi2O3/FEG first used as nitrogen reduction electrocatalyst exhibits excellent electrocatalysis performance and stability for nitrogen reduction reaction in neutral media.

-

The superior electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction activity is attributed to the strong interaction of the Bi 6p band with the N 2p orbitals, binder-free nature of the electrodes, and facile electron transfer through the graphene nanosheets.

Abstract

Electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction reaction is a carbon-free and energy-saving strategy for efficient synthesis of ammonia under ambient conditions. Here, we report the synthesis of nanosized Bi2O3 particles grown on functionalized exfoliated graphene (Bi2O3/FEG) via a facile electrochemical deposition method. The obtained free-standing Bi2O3/FEG achieves a high Faradaic efficiency of 11.2% and a large NH3 yield of 4.21 ± 0.14 \( \upmu{\text{g}}_{{{\text{NH}}_{3} }} \) h−1 cm−2 at − 0.5 V versus reversible hydrogen electrode in 0.1 M Na2SO4, better than that in the strong acidic and basic media. Benefiting from its strong interaction of Bi 6p band with the N 2p orbitals, binder-free characteristic, and facile electron transfer, Bi2O3/FEG achieves superior catalytic performance and excellent long-term stability as compared with most of the previous reported catalysts. This study is significant to design low-cost, high-efficient Bi-based electrocatalysts for electrochemical ammonia synthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Ammonia (NH3) is considered to be a promising hydrogen energy carrier to alleviate the fossil fuel shortage and global climate change, for its high energy density, high hydrogen content, no carbon footprint and being easy to liquefy [1,2,3]. To date, the dominant method for industrial-scale NH3 synthesis still depends on the traditional Haber–Bosch process [4,5,6]. However, this energy-intensive and environmentally hazardous process consumes 2% of the global annual energy and leads to 1% of the world’s CO2 emission [7]. It is thus imperative to develop sustainable and economical techniques for NH3 synthesis at mild conditions.

The electrochemical nitrogen reduction reaction (ENRR) is regarded as an energy-saving and carbon-free process, which can synthesize NH3 at ambient conditions by utilizing renewable energy such as those from wind and solar [8,9,10,11,12]. Unfortunately, the scaled-up application of the ENRR process is seriously hampered by the low ammonia yields and Faraday efficiency due to the extremely weak N2 adsorption, the low solubility of N2 in aqueous electrolytes, and the sluggish cleavage of the N≡N bond [13]. Over the past 5 years, numerous metal-based materials, including metal [7, 14,15,16,17,18], metal oxides [19,20,21], metal sulfides [22, 23], metal nitrides [24], etc., have been developed as electrocatalysts for ENRR. Most of the above metal-based catalysts involving the metallic centers of Au [7], Ru [17], Ni [20], Mo [18, 22], etc., exhibited favorable activity for ENRR by elaborately designing the particle size, crystallinity, heteroatom doping, and/or vacancies. Despite the substantial progress, the ENRR still suffers from the major competitive hydrogen evolution reaction (HER). Therefore, the rational design of the active catalytic centers of efficient ENRR electrocatalysts that can efficiently reduce the large activation barrier of N≡N, accelerate its dissociation and most importantly suppress HER, is still a highly challenging but vitally important issue [25].

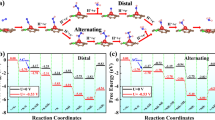

Bismuth-based catalysts are considered to be promising candidates for efficient ENRR in recent years [26,27,28,29,30]. Bi as a main group element with tunable p-electron density and intrinsic less reactive nature can selectively promote the reductive adsorption of N2 to form N2H* without influencing the binding energy of the later intermediates, and also restrict the surface electron accessibility for effectively suppressing the competitive HER process [26,27,28]. Yan et al. demonstrated that overlaping of the Bi 6p bands and the 2p orbitals of the N atom both below and above the Fermi level can offer a lower free-energy change for the potential-determining step and better ENRR activity than typical transition metal catalysts [29]. Most of the Bi-based electrocatalysts for ENRR reported previously are mainly focused on the metallic bismuth (Bi0) [27,28,29]. It was reported that both the defect-rich Bi and 2D mosaic Bi nanosheets have been used for ENRR, and offered excellent selectivity in 0.2 M Na2SO4 (Faradaic efficiency (FE): 11.68% at − 0.6 V vs. RHE) [28] and 0.1 M in Na2SO4 (FE: 10.46 ± 1.45% at − 0.8 V vs. RHE) [31], respectively. As an abundant Bi-based material, Bi2O3 has received much attention in photocatalysis due to its unique electrical and optical properties [32,33,34]. It was also used as a precursor for the synthesis of other Bi-based materials [28]. However, bismuth oxide has hardly been reported for ENRR, with part of reason being that the semiconducting Bi2O3 shows poor charge transport, while the easy aggregation of Bi2O3 instead of nanosized status largely impairs the adsorption and reactivity to N2. Therefore, a robust support is necessary to enhance the conductivity, at the same time offer well dispersion of the Bi2O3 nanoparticles.

Functionalized exfoliated graphene (FEG) acts as an ideal 3D-conductive scaffold for supporting catalysts, which is constructed by ultrathin partially oxidized graphene nanosheets anchoring on the graphite substrate [35,36,37]. The FEG modified by oxygen-containing groups (–OH, –COOH) that provide active defect sites, can act as an excellent substrate for metal oxides deposition when using the metal ions as the precursor [38]. It is the high surface area and excellent electron conductivity of graphene nanosheets that can accelerate the charge transport and keep credible electric contact, resulting in the enormously improved catalytic efficiency [39,40,41,42]. In addition, polymer binder (e.g., Nafion) is widely used for attaching the electrocatalysts to the collectors, which seriously hampers the mass transport and obstructs the charge transmission, and therefore reduces the overall catalytic performance of the electrocatalysts [43, 44]. Therefore, the in situ growth of metal oxides on FEG with highly exposed active sites, superior electron conductivity, and large surface area is vitally important to improve the electrocatalytic performance. Based on the above analysis results, it is reasonable to assume that the composite electrocatalysts composed of well-coupled Bi2O3 and FEG can act as a promising candidate to promote the electrochemical reduction of N2 to NH3.

Herein, we developed a new type of ENRR catalyst by immobilizing Bi2O3 nanoplates onto the surface of FEG, to form the free-standing hybrid material (Bi2O3/FEG), which was then directly used as an electrode for ENRR in different electrolytes under ambient conditions. In this ENRR system, the competitive hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) is expected to be suppressed by the better intrinsic ENRR activity of Bi. Moreover, the highly conductive FEG was utilized to compensate for the semiconducting property of Bi2O3 and eliminate its aggregation. The as-prepared Bi2O3/FEG catalyst exhibits high ENRR activity with a high NH3 yield rate of 4.21 ± 0.14 \( \upmu{\text{g}}_{{{\text{NH}}_{3} }} \) h−1 cm−2, and a favorable FE as high as 11.2% at − 0.5 V versus RHE in 0.1 M Na2SO4 electrolyte, out-performing most reported ENRR catalysts.

2 Experimental

2.1 Synthesis of the Functionalized Exfoliated Graphene (FEG)

The FEG substrate was prepared through an electrochemical exfoliation method according to our previous work with slight modification [45]. The exfoliation process was performed in a typical three-electrode cell using the graphite foil [GF, the exposed surface area is 1 × 1 cm2 (length × width)] as the working electrode, a platinum plate and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the counter and reference electrodes, respectively. First, the GF was scanned between 0.5 and 1.7 V (vs. SCE) using cyclic voltammetry at 15 mV s−1 in 0.5 M K2CO3 electrolyte for ten cycles. Subsequently, the electrode was further treated at a constant potential of 1.8 V (vs. SCE) for 2 h in 0.5 M KNO3 aqueous solution to generate functional groups. Then, the electrode was potential dynamically scanned between − 1.0 and 0.9 V (vs. SCE) at 50 mV s−1 for 50 cycles in 3 M KCl electrolyte to recover the electrical conductivity. Finally, the FEG substrate was rinsed with deionized water and ethanol to remove the residuals.

2.2 Synthesis of the nanosized Bi2O3 Modified FEG (Bi2O3/FEG)

Bi2O3/FEG was synthesized through an electrochemical deposition process. 0.3 g of bismuth chloride (BiCl3) was dissolved into 25 mL ethylene glycol (EG) and stirred at 25 °C for 1 h forming the electrolyte. The electrodeposition process was conducted in a two-electrode cell with a platinum plate as the counter electrode and a piece of FEG (1 × 1 cm2) as the working electrode. Bi2O3 nanoparticles were electrodeposited on FEG at a constant current density of 1 mA cm−2 at ambient temperature for 5 min. The as-synthesized product was washed with tetrahydrofuran and ethanol and subsequently dried in a vacuum oven at 70 °C for 12 h, finally obtaining free-standing Bi2O3/FEG.

2.3 Electrocatalytic ENRR Measurements

Before ENRR tests, the Nafion 117 membrane was cut into small pieces and then treated with 3 wt% H2O2 water solution, deionized water, 1 mol L−1 H2SO4 and deionized water for 1 h at 80 °C, respectively. Finally, the obtained membrane was repeatedly rinsed until neutral pH was obtained and then was preserved in deionized water. Electrochemical measurements were performed in an airtight two-compartment cell at ambient conditions using an electrochemical workstation (CHI 760E), with Bi2O3/FEG or FEG as the working electrode, Pt foil as the counter electrode, and Ag/AgCl (filled with 3.5 M KCl solution) as the reference electrode. The potentials were converted to reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) scale via calibration with the Nernst equation (ERHE = EAg/AgCl + 0.059 pH + 0.205 V). The linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves were collected in 0.1 M Na2SO4 electrolyte saturated with ultrahigh Ar or N2 for 30 min at a sweep rate of 5 mV s−1, respectively.

2.4 Determination of Ammonia

The concentrations of the synthesized NH3 in the electrolyte were measured by a colorimetric method using Nessler’s reagent as the color reagent. For this method, 10 mL electrolyte was mixed with 0.2 mL 50% seignette salt solution. Then 0.2 mL Nessler’s reagent was added and the mixture was allowed still for 10 min. Then the mixture was detected as the absorbance at 420 nm by a UV–Vis spectrometer (Shimadzu UV-2600). A standard curve of the Nessler’s reagent-based colorimetric method is constructed by measuring a series of absorbances for the reference solution with different NH4Cl concentrations (0.00, 0.10, 0.20, 0.30, 0.40, and 0.50 μg mL−1). The background is corrected with a blank solution (as shown in Fig. S1).

An ion-selective electrode meter (Orion Star A214 Benchtop pH/ISE Meter; Thermo Scientific) for NH3 detection was also performed to further verify the reliability of the colorimetric method. The details were according to our previous work [46] (as shown in Supporting Infromation).

2.5 Determination of Hydrazine

The yield of hydrazine in the electrolyte was evaluated via Watt and Chrisp method. The hydrazine chromogenic reagent is a mixture of para-(dimethylamino) benzaldehyde (0.599 g), ethanol (300 mL) and concentrated HCl (30 mL). After 2 h ENRR reaction, 2 mL of the above reagent was added into 2 mL of the electrolyte and then the mixture was detected at 460 nm. The concentration-absorbance curve was calibrated using standard hydrazine hydrate solution with a serious of concentrations (Y = 2.225 X + 0.03, R2 = 0.99913) (as shown in Fig. S2).

2.6 Calculation of Faradaic Efficiency (FE) and NH3 Yield Rate

The FE for NH3 production and NH3 yield rate were calculated at an applied potential as follow (Eqs. 1 and 2):

where CNH3 is the concentration of NH3, V is the volume of the electrolyte, F is the Faraday constant of 96,485 C mol−1, Q is the total charge passed through the electrochemical system, t is the reaction time of ENRR process, and m is the mass of the catalytic active site, i.e., the Bi atoms of Bi2O3 molecule on the surface of the Bi2O3/FEG electrode.

2.7 Calculation of Equilibrium Potential

At the very beginning of the ENRR, the newly produced ammonia formed a type of coordination with water, as shown in Eq. 3:

The equilibrium potential for ENRR under our experimental conditions is calculated using the Nernst equation as shown in Eq. 4, assuming 1 atm of N2 and an NH3·H2O concentration of 0.5 × 10−5 M in the solution [46].

where Eo = 0.092 V is the standard potential for the above half reaction of ENRR, R = 8.314 J mol−1 K−1 is the molar gas constant, n = 6 is the number of electrons transferred in Eq. 3, F = 96,485 C mol−1 is the Faraday constant, T = 298.15 K is the reaction temperature in this experimental condition.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Materials Characterization

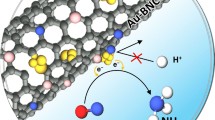

Scheme 1 illustrates the synthesis procedure to obtain the free-standing Bi2O3/FEG hybrid. Typically, the FEG substrate was prepared through electrochemical exfoliating the graphite foil into functionalized exfoliated graphene nanosheets with abundant oxygen functional groups. Sequentially, the Bi2O3 nanoplates were uniformly immobilized onto the FEG with BiCl3 as the precursor through a facile electrochemical deposition method, during which the mass loading and the morphology of the Bi2O3 can be easily controlled by adjusting the electrolyte concentration and deposition duration. The actual weight of Bi in Bi2O3/FEG electrodes was determined to be approximately 0.74 mg cm−2 by measuring the weight before and after the electrodeposition process, followed by ICP-AES confirmation.

The morphology and microstructure of as-prepared Bi2O3/FEG were investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Figure 1a shows the SEM images of the as-prepared Bi2O3/FEG hybrid. It can be clearly observed that, after electrochemical deposition, Bi2O3 nanoplates are uniformly grown on the surface of the loosely packed FEG layers. This is due to the fact that oxygen functional groups in graphene nanosheets play a structure-directing role in the electrochemical deposition. The Bi3+ precursors can be captured through coordination bonding with the hydroxyl and carboxyl groups in graphene nanosheets, which were introduced in the electrochemical exfoliation process [38]. Then this uniform deposition of Bi2O3 in the nanosheets of FEG can be achieved by the following electrochemical process. The SEM and corresponding elemental (Bi, C, and O) mapping images of Bi2O3/FEG are shown in Fig. 1b. Uniform distribution of bismuth (from Bi2O3 nanoplates) combined with the carbon and oxygen can be detected over the whole area of the Bi2O3/FEG nanosheet, further demonstrating the presence of homogeneous Bi2O3 nanoplates on the graphene sheet of FEG. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of the as-prepared Bi2O3/FEG hybrid is shown in Fig. 1c, which further confirms the Bi2O3 nanoplates with a particle size of about 5 nm evenly decorated on the graphene nanosheets of FEG. The TEM image of Bi2O3/FEG in Fig. 1c (inset) further displays that numerous Bi2O3 nanoplates are homogeneously dispersed on the surface of FEG. As shown in Fig. 1c, the high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image of Bi2O3/FEG hybrid reveals the uniform distributed Bi2O3 on the surface of FEG with well-defined nanocrystalline nature. The magnification corresponding HRTEM images in the circle area of Fig. 1c reveal the lattice fringes of 0.25 nm (Fig. 1d), which could be well indexed to the (102) plane of Bi2O3. The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern indicates the monocrystalline nature of Bi2O3 nanoplates and reveals the (102), (100), and (002) planes of Bi2O3 (inset of Fig. 1d), further confirming the existence of Bi2O3 in FEG.

a SEM images of Bi2O3/FEG with the inset showing the high-magnification SEM image. b SEM and corresponding elemental (Bi, C, and O) mapping images of Bi2O3/FEG. c HRTEM images of Bi2O3/FEG, the inset shows the TEM image. d Corresponding HRTEM images in the circle area, the inset shows the SAED pattern. e XPS spectra of Bi2O3/FEG and the FEG substrate; inset is the magnified image. f Bi 4f XPS spectrum of Bi2O3/FEG

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of pure FEG and the as-prepared Bi2O3/FEG hybrid are displayed in Fig. S3. The strong peak at 26.3° of FEG is indexed to the (002) plane of graphene [36] that confirms the successful synthesis of pure FEG. It is found that Bi2O3/FEG hybrid also exhibited a characteristic peak of graphene at 26.6°. This intense and sharp peak indicates highly crystalline graphene nature of Bi2O3/FEG, which is beneficial to the electron transfer. No characteristic diffraction peaks of Bi2O3 are observed because of its lower loading content. This also implies the good dispersion of the very small Bi2O3 particles on the FEG.

The full-range X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of FEG and the as-prepared Bi2O3/FEG hybrid are shown in Fig. 1e, and it was observed that two peaks appeared at 285.6 and 532.0 eV, corresponding to the C 1s and O 1s core level spectrum, respectively. Moreover, the presence of Bi electrons was confirmed by the XPS analysis of Bi2O3/FEG, the three doublet peaks at around 690.0, 455.0, and 162.0 eV, corresponding to the Bi 4p, Bi 4d, and Bi 4f electrons, indicating that some Bi2O3 was immobilized on the FEG. In the high-solution Bi 4f XPS spectrum (Fig. 1f), two main peaks centered at 159.8 and 165.1 eV can be identified as Bi 4f7/2 and Bi 4f5/2 signals of Bi3+, respectively, in accordance with previous reports [47]. And the 0.8 eV blueshift of Bi 4f7/2 and Bi 4f5/2 peaks due to charge transfer from Bi3+ center to the FEG. The results from the above characterizations demonstrate that FEG is an excellent substrate for the deposition and fixation of Bi2O3 nanoplates. The incorporation of Bi2O3 nanoplates into the FEG prevented the aggregation of Bi2O3 nanoplates and provided more reactive sites, that may improve its performance of ENRR.

The contact angle measurement was then performed to investigate the hydrophilicity of FEG and Bi2O3/FEG. It can be seen from Fig. S4a, the surface of FEG whose contact angle is approximately 83° exhibits strong hydrophilicity, which is mainly due to the oxygen functional groups (–OOH and –OH) of FEG. After decorated with Bi2O3, the contact angle of the as-prepared Bi2O3/FEG increases to around 110° (Fig. S4b), indicating a hydrophobic property. This hydrophobicity is expected to be helpful in promoting the ENRR performance by providing strong interaction with N2 gas [48].

3.2 Electrochemical Nitrogen Reduction

The ENRR performance of the prepared Bi2O3/FEG catalyst was evaluated in N2-saturated 0.1 M Na2SO4 electrolyte under ambient conditions using a two-compartment electrochemical cell, separated by a Nafion 117 membrane. The free-standing Bi2O3/FEG hybrid material was directly used as the working electrode, with a platinum plate as the counter electrode and Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode (configuration shown in Fig. 2a). The feeding gas (ultrahigh purity N2, 99.999%) was continuously bubbled into the cathode via a bubbler during the experiment at the flow rate of 10 mL min−1. All potentials were reported on a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) scale. First, we studied the potential dependence of ENRR activity of Bi2O3/FEG by LSV in Ar- and N2-saturated 0.1 M Na2SO4 electrolytes at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1. As shown in Fig. S5, the LSV curves of Bi2O3/FEG in Ar and N2-saturated electrolytes exhibit the same shape, but a higher current density is achieved in the N2-saturated electrolyte when potential is more negative than − 0.4 V, implying that Bi2O3/FEG possesses catalytic activity for ENRR reaction.

a Schematic reaction cell for ENRR. b Faradic efficiency and NH3 yield rate at various potentials in 0.1 M Na2SO4 electrolyte (determined by the Nessler’s reagent). c Chronoamperometry results at the corresponding potentials. d FE and NH3 yield rate at various potentials in 0.1 M Na2SO4 electrolyte (determined by ion-selective electrode meter)

Further, chronoamperometry tests at a series of potentials were carried out to explore the catalytic activity and identify the optimal potential of the Bi2O3/FEG electrode for the ENRR (Fig. 2b). The concentration of the produced ammonia in solution after the 2 h electrolysis was determined independently by a spectrophotometry method with Nessler’s reagent as a color reagent, while the possible N2H4 by-product was detected by a spectrophotometry method with p-C9H11NO as an indicator.

The average ammonia yields and the corresponding FE of Bi2O3/FEG at potentials from − 0.4 to − 0.8 V (vs. RHE) in 0.1 M Na2SO4 are plotted in Fig. 2b. The FE value at − 0.4 V (vs. RHE) is 7.1%, and then the ENRR rate and FE rise with the negative potential increasing until − 0.5 V (vs. RHE), where the relatively high NH3 yield and the maximum FE value can reach 4.21 ± 0.14 \( \upmu{\text{g}}_{{{\text{NH}}_{3} }} \) h−1 cm−2 (i.e., 5.68 \( \upmu{\text{g}}_{{{\text{NH}}_{3} }} \) mg −1Bi h−1) and 11.2%, respectively. No N2H4 by-product has been detected, indicating the good selectivity of the Bi2O3/FEG catalyst for ENRR. Meanwhile, ENRR was also conducted on FEG in N2-saturated 0.1 M Na2SO4 solution at − 0.5 V (vs. RHE) to verify the source of NH3. No NH3 was detected, indicating that FEG had no catalytic activity toward ENRR for the production of NH3, and the contribution of NH3 yield from the impurities of FEG was also negligible. Therefore, it can be inferred here that the Bi2O3 in Bi2O3/FEG played a decisive role in the ENRR, while FEG possessed no activity toward the ENRR.

This ENRR catalytic performance of the as-prepared Bi2O3/FEG hybrid material can even comparable to the yields and efficiencies catalyzed by metal-based nanocatalysts as shown in Table S1. For example, Bi nanosheets (FE of 10.46% with an NH3 yield rate of 2.54 μg h−1 cm−2 at − 0.8 V (vs. RHE) in 0.1 M Na2SO4 electrolyte) [31] and Au nanorod (FE of 4.02% with an NH3 yield rate of 1.648 μg h−1 cm−2 at − 0.2 V vs. RHE in 0.1 M KOH electrolyte) [49]. The excellent ENRR performance of the as-prepared Bi2O3/FEG hybrid material is mainly due to the following reasons. On the one hand, this high ENRR activity is primarily attributed to the Bi center from Bi2O3, which can effectively inhibit the side reaction of HER during ENRR process by binding *N2H more strongly without affecting the binding energy of *NH2 or *NH [26, 31], and offer a lower free-energy change than traditional transition mental for a better ENRR activity [29]. On the other hand, the nanosized Bi2O3 and the large surface of FEG, which provide abundant active sites, may insure the efficient ENRR reaction. Besides, the facile electron and mass transfer process from the graphene nanosheets of Bi2O3/FEG accelerate the ENRR process through promoting the electron transport, and the hydrophobic property of Bi2O3/FEG provides strong interaction with N2 gas further accelerate the ENRR.

In addition, as shown in Fig. 2c, the current density at different potentials behaves good stability, which can be attributed to the well dispersion and anchoring of the nanosized Bi2O3 nanoplates on the graphene nanosheets. Unexpectedly, though the NH3 yield reaches the highest average value of 5.8 ± 0.15 \( \upmu{\text{g}}_{{{\text{NH}}_{3} }} \) h−1 cm−2 at − 0.8 V (vs. RHE), the FE values decrease obviously when the applied potentials are more negative than − 0.5 V (vs. RHE). A plausible explanation is that the ENRR in this system was in a N2 diffusion-controlled mode, and the feeding gas N2 has extremely low solubility in aqueous electrolyte. At higher negative potentials, the competing reaction (HER) was dominant [46], so the surface of Bi2O3/FEG was mainly occupied by the hydrogen molecules which would impede the mass transfer of N2 to the surface of Bi2O3/FEG, and thus strongly reduce the ENRR selectivity.

The concentrations of the NH3 synthesized by Bi2O3/FEG at potentials from − 0.4 to − 0.8 V (vs. RHE) in 0.1 M Na2SO4 were also determined by ion-selective electrode meter to confirm the reliability of this colorimetric method for ammonia detection. As shown in Fig. 2d, the corresponding average NH3 yields and FE were almost identical to that of determined by the Nessler’s reagent (Fig. 2b) within experimental error, suggesting that it was reliable to use the Nessler’s reagent for the quantitative analysis of the produced NH3.

Subsequently, chronoamperometry tests in N2-saturated 0.1 M KOH or 0.05 M H2SO4 electrolyte under the same experimental conditions as that of in Na2SO4 electrolyte were carried out to explore the catalytic activity of the Bi2O3/FEG in strong basic and acidic media. As shown in Fig. 3a, the optimum average NH3 yield rate 3.07 ± 0.11 \( \upmu{\text{g}}_{{{\text{NH}}_{3} }} \) h−1 cm−2 in thestrong basic electrolyte occurred at − 0.5 V (vs. RHE), indicating a wide pH response of Bi2O3/FEG. However, the relatively low FE of 0.59% may be caused by the high current density implying dominant HER (Fig. S7). Furthermore, the robust current stability of Bi2O3/FEG in 0.1 M KOH has been confirmed for 2 h electrolysis, as shown in Fig. 3b, indicating ideal stability of Bi2O3/FEG in the strong basic electrolyte. The NH3 yields and the corresponding FE of Bi2O3/FEG at potentials from -0.2 to -0.6 V (vs. RHE) in 0.05 M H2SO4 are plotted in Fig. 3c. The NH3 yield at − 0.2 V (vs. RHE) is 2.8 \( \upmu{\text{g}}_{{{\text{NH}}_{3} }} \) h−1 cm−2 with the FE of 1.36%, then the NRR rate and FE decrease sharply with the potential shifted negatively. The dissatisfactory catalytic performance in 0.05 M Na2SO4 electrolyte should attribute to the instability of Bi2O3 and the drastic HER competing reaction in acid medium. Comparing the optimum FE and NH3 yield rates of Bi2O3/FEG in different electrolytes as shown in Fig. 3d, Bi2O3/FEG exhibits excellent electrocatalysis performance and stability for ENRR in neutral media even better than that in strong basic and acidic media under the same ambient conditions. It is highly desired to develop electrocatalysts for efficient and durable ENRR catalysis at neutral conditions, which is beneficial for alleviating the serious environment sufferings, reducing equipment and catalyst corrosions, lower the cost of the whole ENRR process, and further accelerating the practical applications of ENRR.

a FE and NH3 yield rate at various potentials in 0.1 M KOH electrolyte (determined by the Nessler’s reagent). b Chronoamperometry results at the corresponding potentials. c FE and NH3 yield rate at various potentials in 0.05 M H2SO4 electrolyte (determined by the Nessler’s reagent). d Optimum FE and yield rates of NH3 in different electrolytes (at − 0.5 V vs. RHE, determined by the Nessler’s reagent)

The stability of the Bi2O3/FEG was evaluated by consecutive recycling electrolysis and long-term chronoamperometry test at − 0.5 V (vs. RHE) in 0.1 M Na2SO4. As shown in Fig. 4a, no obvious change in the NH3 yield and Faradaic efficiency could be observed during five consecutive recycling electrolysis, which suggests the excellent stability of Bi2O3/FEG for NH3 synthesis at ambient conditions. In addition, slight degradation of current density in the process of long-term chronoamperometry test is detected for 12 h at − 0.5 V (vs. RHE) (Fig. 4b). Moreover, no obvious variation of the NH3 yield rate and FE could be observed after 12 h long-term chronoamperometry test, indicating the high robustness of Bi2O3/FEG toward ambient NH3 synthesis. Furthermore, both the compositions and Bi2O3 nature of the Bi2O3/FEG could be well maintained after the long-term electrocatalysis reaction when comparing TEM images (Fig. 4c) and XPS (Fig. 4d) before and after the reaction. All these observations demonstrate the excellent electrochemical durability of the Bi2O3/FEG for the ENRR, which is another crucial factor for the enhancement of ENRR performances.

a FE and NH3 yield rates of Bi2O3/FEG calculated after consecutive recycling electrolysis in N2-saturated 0.1 M K2SO4 solution at − 0.5 V (vs. RHE) for 2 h. b 12 h durability test for Bi2O3/FEG toward ENRR at − 0.5 V (vs. RHE), inset: the corresponding FE and NH3 yield rate after durability test. c The HRTEM image of Bi2O3/FEG after ENRR. d Bi 4f XPS spectrum of Bi2O3/FEG after ENRR

4 Conclusions

In summary, a highly efficient hybrid ENRR electrocatalyst composed of nanosized Bi2O3 supported on FEG was developed. Due to the synergistic effect between the nanosized Bi2O3 and the large surface area of FEG, the Bi2O3/FEG hybrid exhibited the superb electrocatalytic performance toward ENRR at a low overpotential of − 0.5 V (vs. RHE) in the neutral electrolyte and under ambient temperature and pressure. The FE of Bi2O3/FEG in 0.1 M Na2SO4 electrolyte is 11.2% with the NH3 yields of 5.68 \( \upmu{\text{g}}_{{{\text{NH}}_{3} }} \) mg −1Bi h−1, which is superior to that of most state-of-the-art ENRR electrocatalysts reported up to date. The high ENRR activity is attributed to the Bi center from Bi2O3 during the ENRR process with the help of the facile electron transfer process from the graphene nanosheets of FEG. This work opens an avenue to rational designing of Bi-based carbon hybrid electrocatalysts and highlights the catalytic center engineering strategy to effectively manipulate the catalytic performance of electrocatalysts.

References

Z.Q. Wang, K. Zheng, S.L. Liu, Z.C. Dai, Y. Xu, X.N. Li, H.J. Wang, L. Wang, Electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction to ammonia by Fe2O3 nanorod array on carbon cloth. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 13, 11754–11759 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b01991

H. Cheng, L.X. Ding, G.F. Chen, L.L. Zhang, J. Xue, H.H. Wang, Nitrogen reduction reaction: molybdenum carbide nanodots enable efficient electrocatalytic nitrogen fixation under ambient conditions. Adv. Mater. 46, 1870350 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201870350

V. Rosca, M. Duca, M.T. de Groot, M.T.M. Koper, Nitrogen cycle electrocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 6, 2209–2244 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1021/cr8003696

C.D. Lv, C.S. Yan, G. Chen, Y. Ding, J.X. Sun, Y.S. Zhou, G.H. Yu, An amorphous noble-metal-free electrocatalyst that enables nitrogen fixation under ambient conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 21, 6073–6076 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201801538

C.J.M. Van der Ham, M.T.M. Koper, D.G.H. Hetterscheid, Challenges in reduction of dinitrogen by proton and electron transfer. Chem. Soc. Rev. 15, 5183–5191 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CS00085D

H.V. Doan, H.A. Hamzah, P.K. Prabhakaran, C. Petrillo, V.P. Ting, Hierarchical metal–organic frameworks with macroporosity: synthesis, achievements, and challenges. Nano-Micro Lett. 11, 54 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-019-0286-9

H.J. Wang, H.J. Yu, Z.Q. Wang, Y.H. Li, Y. Xu, X.N. Li, H.R. Xue, L. Wang, Electrochemical fabrication of porous Au film on Ni foam for nitrogen reduction to ammonia. Small 6, 1804769 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201804769

G.F. Chen, X.R. Cao, S.Q. Wu, X.Y. Zeng, L.X. Ding, M. Zhu, H.H. Wang, Ammonia electrosynthesis with high selectivity under ambient conditions via a Li+ incorporation strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 29, 9771–9774 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.7b04393

M.M. Shi, D. Bao, B.R. Wulan, Y.H. Li, Y.F. Zhang, J.M. Yan, Q. Jiang, Au sub-nanoclusters on TiO2 toward highly efficient and selective electrocatalyst for N2 conversion to NH3 at ambient conditions. Adv. Mater. 17, 1606550 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201606550

M. Bat-Erdene, G.R. Xu, M. Batmunkh, A.S.R. Bati, J.J. White et al., Surface oxidized two-dimensional antimonene nanosheets for electrochemical ammonia synthesis under ambient conditions. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 4735–4739 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TA13485A

Y.F. Li, T.S. Li, X.J. Zhu, A.A. Alshehri, K.A. Alzahrani, S.Y. Lu, X.P. Sun, DyF3: an efficient electrocatalyst for N2 fixation to NH3 under ambient conditions. Chem. Asian J. 4, 487–489 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/asia.201901624

M.G. Wu, J.Q. Liao, L.X. Yu, R.T. Lv, P. Li et al., 2020 Roadmap on carbon materials for energy storage and conversion. Chem. Asian J. 15(7), 995–1013 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/asia.201901802

X.H. Guo, Y.P. Zhu, T.Y. Ma, Lowering reaction temperature: electrochemical ammonia synthesis by coupling various electrolytes and catalysts. J. Energy Chem. 6, 1107–1116 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2017.09.012

C.Y. Ling, X.W. Bai, Y.X. Ouyang, A.J. Du, J.L. Wang, Single molybdenum atom anchored on N-doped carbon as a promising electrocatalyst for nitrogen reduction into ammonia at ambient conditions. J. Phys. Chem. C 29, 16842–16847 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b05257

T.W. He, S.K. Matta, A.J. Du, Single tungsten atom supported on N-doped graphyne as a high-performance electrocatalyst for nitrogen fixation under ambient conditions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 3, 1546–1551 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C8CP06978F

Y. Yao, H.J. Wang, X.Z. Yuan, H. Li, M.H. Shao, Electrochemical nitrogen reduction reaction on ruthenium. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 1336–1341 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.9b00699

H.J. Wang, Y.H. Li, C.J. Li, K. Deng, Z.Q. Wang, Y. Xu, X.N. Li, H.R. Xue, L. Wang, One-pot synthesis of bi-metallic PdRu tripods as an efficient catalyst for electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction to ammonia. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 801–805 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C8TA09482A

D.S. Yang, T. Chen, Z.J. Wang, Electrochemical reduction of aqueous nitrogen (N2) at a low overpotential on (110)-oriented Mo nanofilm. J. Mater. Chem. A 36, 18967–18971 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/C7TA06139K

H.T. Du, X.X. Guo, R.M. Kong, F.L. Qu, Cr2O3 nanofiber: a high-performance electrocatalyst toward artificial N2 fixation to NH3 under ambient conditions. Chem. Commun. 91, 12848–12851 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/C8CC07186A

K. Chu, Y.P. Liu, J. Wang, H. Zhang, NiO nanodots on graphene for efficient electrochemical N2 reduction to NH3. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 3, 2288–2295 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.9b00102

T. Xu, D.W. Ma, C.B. Li, Q. Liu, S.Y. Lu, A.M. Asiri, C. Yang, X.P. Sun, Ambient electrochemical NH3 synthesis from N2 and water enabled by ZrO2 nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 25, 3673–3676 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1039/C9CC10087C

X.H. Li, X. Ren, X.J. Liu, J.X. Zhao, X. Sun et al., A MoS2 nanosheet–reduced graphene oxide hybrid: an efficient electrocatalyst for electrocatalytic N2 reduction to NH3 under ambient conditions. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 2524–2528 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C8TA10433F

P.X. Li, W.Z. Fu, P.Y. Zhuang, Y.D. Cao, C. Tang et al., Amorphous Sn/crystalline SnS2 nanosheets via in situ electrochemical reduction methodology for highly efficient ambient N2 fixation. Small 40, 1902535 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201902535

H.Y. Jin, L.Q. Li, X. Liu, C. Tang, W.J. Xu et al., Nitrogen vacancies on 2D layered W2N3: a stable and efficient active site for nitrogen reduction reaction. Adv. Mater. 32, 1902709 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201902709

G.F. Chen, S.Y. Ren, L.L. Zhang, H. Cheng, Y.R. Luo, K.H. Zhu, L.X. Ding, H.H. Wang, Nitrogen reduction reactions: advances in electrocatalytic N2 reduction—strategies to tackle the selectivity challenge. Small Methods 6, 1970016 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/smtd.201970016

J.H. Montoya, C. Tsai, A. Vojvodic, J.K. Nørskov, The challenge of electrochemical ammonia synthesis: a new perspective on the role of nitrogen scaling relations. Chemsuschem 13, 2180–2186 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.201500322

Z. Wang, F. Gong, L. Zhang, R. Wang, L. Ji et al., Electrocatalytic hydrogenation of N2 to NH3 by MnO: experimental and theoretical investigations. Adv. Sci. 1, 1801182 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.201801182

Y. Wang, M.M. Shi, D. Bao, F.L. Meng, Q. Zhang et al., Generating defect-rich bismuth for enhancing the rate of nitrogen electroreduction to ammonia. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 28, 9464–9469 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201903969

Y.C. Hao, Y. Guo, L.W. Chen, M. Shu, X.Y. Wang et al., Promoting nitrogen electroreduction to ammonia with bismuth nanocrystals and potassium cations in water. Nat. Catal. 5, 448–456 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-019-0241-7

F.Y. Wang, X. Lv, X.J. Zhu, J. Du, S.Y. Lu et al., Bi nanodendrites for efficient electrocatalytic N2 fixation to NH3 under ambient conditions. Chem. Commun. 14, 2107–2110 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1039/C9CC09803H

L.Q. Li, C. Tang, B.Q. Xia, H.Y. Jin, Y. Zheng, S.Z. Qiao, Two-dimensional mosaic bismuth nanosheets for highly selective ambient electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction. ACS Catal. 4, 2902–2908 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.9b00366

Y. Peng, M. Yan, Q.G. Chen, C.M. Fan, H.Y. Zhou, A.W. Xu, Novel one-dimensional Bi2O3–Bi2WO6 p–n hierarchical heterojunction with enhanced photocatalytic activity. J. Mater. Chem. A 22, 8517–8524 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1039/C4TA00274A

H.J. Lu, Q. Hao, T. Chen, L.H. Zhang, D.M. Chen, C. Ma, W.Q. Yao, Y.F. Zhu, A high-performance Bi2O3/Bi2SiO5 p–n heterojunction photocatalyst induced by phase transition of Bi2O3. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.05.069

S. Sanna, V. Esposito, J.W. Andreasen, J. Hjelm, W. Zhang et al., Enhancement of the chemical stability in confined δ-Bi2O3. Nat. Mater. 5, 500–504 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4266

Y. Song, X. Cai, X.X. Xu, X.X. Liu, Integration of nickel–cobalt double hydroxide nanosheets and polypyrrole films with functionalized partially exfoliated graphite for asymmetric supercapacitors with improved rate capability. J. Mater. Chem. A 28, 14712–14720 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5TA02810H

J.H. Cao, K.X. Wang, J.Y. Chen, C.J. Lei, B. Yang, Z.J. Li, L.C. Lei, Y. Hou, K. Ostrikov, Nitrogen-doped carbon-encased bimetallic selenide for high-performance water electrolysis. Nano-Micro Lett. 11, 67 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-019-0299-4

Y.L. Yang, Y. Tang, H.M. Jiang, Y.M. Chen, P.Y. Wan et al., 2020 Roadmap on gas-involved photo- and electro-catalysis. Chin. Chem. Lett. 12, 2089–2109 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2019.10.041

Y.W. Cheng, H.B. Zhang, C.V. Varanasi, J. Liu, Improving the performance of cobalt–nickel hydroxide-based self-supporting electrodes for supercapacitors using accumulative approaches. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 3314–3321 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1039/C3EE41143E

D. Chen, L.H. Tang, J.H. Li, Graphene-based materials in electrochemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 8, 3157–3180 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1039/B923596E

S. Mukherjee, Z. Ren, G. Singh, Beyond graphene anode materials for emerging metal ion batteries and supercapacitors. Nano-Micro Lett. 10, 70 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-018-0224-2

Y. Sun, W. Zhang, J. Tong, Y. Zhang, S.Y. Wu et al., Significant enhancement of visible light photocatalytic activity of the hybrid B12-PIL/rGO in the presence of Ru(bpy) 2+3 for DDT dehalogenation. RSC Adv. 31, 19197–19204 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/C7RA02062G

Y.L. Yang, M.G. Wu, X.W. Zhu, H. Xu, S. Ma et al., 2020 Roadmap on two-dimensional nanomaterials for environmental catalysis. Chin. Chem. Lett. 12, 2065–2088 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2019.11.001

Y.B. Xu, Y. Song, Z.G. Zhang, A binder-free fluidizable Mo/HZSM-5 catalyst for non-oxidative methane dehydroaromatization in a dual circulating fluidized bed reactor system. Catal. Today (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2016.03.037

C.H. Jiang, Z.X. Ye, H.T. Ye, Z.M. Zou, Li4Ti5O12@carbon cloth composite with improved mass loading achieved by a hierarchical polypyrrole interlayer assisted hydrothermal process for robust free-standing sodium storage. Appl. Surf. Sci. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.144464

J.C. Liu, H. Li, M. Batmunkh, X. Xiao, Y. Sun, Q. Zhao, X. Liu, Z.H. Huang, T.Y. Ma, Structural engineering to maintain the superior capacitance of molybdenum oxides at ultrahigh mass loadings. J. Mater. Chem. A 41, 23941–23948 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TA04835A

B. Yu, H. Li, J. White, S. Donne, J.B. Yi et al., Tuning the catalytic preference of ruthenium catalysts for nitrogen reduction by atomic dispersion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 6, 1905665 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201905665

S.B. Liu, X.F. Lu, J. Xiao, X. Wang, X.W. Lou, Bi2O3 nanosheets grown on multi-channel carbon matrix to catalyze efficient CO2 electroreduction to HCOOH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39, 13828–13833 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201907674

Q. Qin, M. Oschatz, Overcoming chemical inertness under ambient conditions: a critical view on recent developments in ammonia synthesis via electrochemical N2 reduction by asking five questions. ChemElectroChem 4, 878–889 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/celc.201901970

D. Bao, Q. Zhang, F.L. Meng, H.X. Zhong, M.M. Shi et al., Electrochemical reduction of N2 under ambient conditions for artificial N2 fixation and renewable energy storage using N2/NH3 cycle. Adv. Mater. 3, 1604799 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201604799

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Liaoning Revitalization Talents Program—Pan Deng Scholars (XLYC1802005), Liaoning BaiQianWan Talents Program, the National Science Fund of Liaoning Province for Excellent Young Scholars, Science and Technology Innovative Talents Support Program of Shenyang (RC180166), Australian Research Council (ARC) through Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE150101306) and Linkage Project (LP160100927), Faculty of Science Strategic Investment Funding of University of Newcastle, and CSIRO Newcastl Energy Centre.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Y., Deng, Z., Song, XM. et al. Bismuth-Based Free-Standing Electrodes for Ambient-Condition Ammonia Production in Neutral Media. Nano-Micro Lett. 12, 133 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00444-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00444-y