Article Highlights

-

A green low-cost route without the acid washing step is used to prepare the N,O-codoped egg-box-like carbons.

-

The obtained carbons possess moderate N, O contents and tuned transfer channels with three-dimensional (3D) egg-box-like structures.

-

The fabricated electrode exhibits high areal capacitance and long-term cycle stability.

Abstract

Functional carbonaceous materials for supercapacitors (SCs) without using acid for post-treatment remain a substantial challenge. In this paper, we present a less harmful strategy for preparing three-dimensional (3D) N,O-codoped egg-box-like carbons (EBCs). The as-prepared EBCs with opened pores provide plentiful channels for ion fast transport, ensure the effective contact of EBCs electrodes and electrolytes, and enhance the electron conduction. The nitrogen and oxygen atoms doped in EBCs improve the surface wettability of EBC electrodes and provide the pseudocapacitance. Consequently, the EBCs display a prominent areal capacitance of 39.8 μF cm−2 (340 F g−1) at 0.106 mA cm−2 in 6 M KOH electrolyte. The EBC-based symmetric SC manifests a high areal capacitance to 27.6 μF cm−2 (236 F g−1) at 0.1075 mA cm−2, a good rate capability of 18.8 μF cm−2 (160 F g−1) at 215 mA cm−2 and a long-term cycle stability with only 1.9% decay after 50,000 cycles in aqueous electrolyte. Impressively, even in all-solid-state SC, EBC electrode shows a high areal capacitance of 25.0 μF cm−2 (214 F g−1) and energy density of 0.0233 mWh cm−2. This work provides an acid-free process to prepare electrode materials from industrial by-products for advanced energy storage devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Supercapacitors (SCs) with high power density and rapid charge rates have received extensive attention in the fields of energy storage and conversion [1,2,3,4]. A SC is mainly composed of the current collector, electrolyte, and electrode [5]. The properties of SC largely depend on the electrode materials, e.g., carbonaceous materials (CMs) [6, 7], metal oxides [8], conductive polymers [9], and their composites [10,11,12]. CMs have become the prime choice of electrode materials for SCs due to their excellent electrical conductivity, versatile porosity and high surface area [13,14,15]. A substantial number of strategies have been reported for the preparation of porous CMs [16,17,18]. Further, the introduction of heteroatoms in CMs can improve the electrical conductivity, enhance the surface wettability of carbonaceous electrodes, and provide additional pseudocapacitance [19,20,21]. Nevertheless, the preparation process of CMs is usually complicated and costly. The corrosive chemical reagents not only corrode the equipment but also produce environment pollutants. For instance, N-doped porous CMs via SiO2 template showed a high areal capacitance of 18.6 μF cm−2 [22]. However, the removal of the SiO2 template required the use of corrosive HF solution, which creates an environmental issue [23]. Therefore, an acid-free process to synthesize porous CMs for SCs is urgently sought.

Coal tar pitch (CTP), which is a residue fraction from the distillation of coal tar, possesses abundant polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which can be aromatized and polymerized to form diverse cross-linked nanostructures [24, 25]. In this paper, we report a less harmful route to prepare three-dimensional (3D) N,O-codoped egg-box-like carbons (EBCs) from CTP. The as-achieved EBCs feature opened structures with large specific surface areas and many channels for ion transport, which can ensure the effective contact between electrodes and electrolytes. Moreover, EBCs with doped heteroatoms (N and O) can further improve the electrical conductivity and boost the surface wettability of EBCs. The as-prepared EBCs display a high areal capacitance, a satisfactory rate capability and cycle stability. Impressively, even in all-solid-state SCs, the EBC electrode also presents a high areal capacitance and energy density.

2 Experimental

2.1 Synthesis of EBCs

CTP was received from Maanshan Iron & Steel Co. Ltd. in China, and other chemicals were received from Aladdin Co. Ltd. In a typical procedure, 2 g CTP and 8 g K2CO3 were ground and mixed in the solid state. The resultant mixture was dispersed onto the 2 g carbon cloth in the corundum boat in a horizontal tube oven, subsequently heated to T °C (T = 750, 800, and 850) with a ramp of 5 °C min−1 in flowing ammonia of 10 mL min−1 and kept for 1 h at T °C. The obtained samples were washed several times by using distilled water, subsequently dried at 110 °C for 24 h. The final products were denominated as EBC750, EBC800, and EBC850 when the heat treatment temperature (T) was set at 750, 800, and 850 °C, respectively.

2.2 Characterization

The EBC materials were characterized by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM,), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), Raman spectroscopy, and a nitrogen adsorption/desorption technique. The elemental analysis was performed using the elemental analyzer. The conductivities of the EBCs were measured by a four-probe method using a source measure unit. The contact angle of EBC electrodes was carried out by the OCA15Pro contact angle tester. Please refer to the Supplementary File for details.

2.3 Electrochemical Test of EBC Electrodes

EBC (90 wt%) and polytetrafluoroethylene (10 wt%) were blended in deionized water without the addition of a conductive agent to make the slurry, subsequently rolled into film and cut into round films (12 mm in diameter), and then dried at 110 °C for 2 h. The round films were pressed onto nickel foam at 20 MPa, followed by immersion in 6 M KOH aqueous electrolyte in vacuum. A coin-type SC was fabricated with two immersed round films and separated by polyethylene membrane. The areal loading of active material on each EBC electrode is ca. 2.15 mg cm−2. The total mass of the current collector and active material is ca. 32 mg.

The fabrication of all-solid-state SC is described as follows: Polymeric gel electrolyte of KOH/polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) was prepared according to the reported method [26], which involved stirring 25 mL deionized water, 1 g KOH and 1 g PVA at 95 °C for 2 h. The EBC800 electrodes were soaked in KOH/PVA electrolyte for 1 min and then dried in room temperature conditions for 24 h. The all-solid-state SC was assembled with two similar soaked EBC800 electrodes. The areal loading of active material on EBC800 electrode is ca. 2.18 mg cm−2. For the electrochemical measurements of SCs and the calculation methods for gravimetric capacitance, areal capacitance, coulumbic efficiency, energy density and average power density, please refer to the Supplementary File.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Structure Characterization

The FESEM images in Fig. 1a–c show 3D interconnected egg-box-like structures with opened pores in the pores of the as-prepared EBCs. The size of the opened pores in EBC750 is ca. 0.4–2 μm (Fig. 1a). The size of the pores in Fig. 1b is larger than that in Fig. 1a due to the tailor/activation function of K2CO3 as the temperature increases. As expected, some egg-box-like structures are broken due to the highest heat treatment temperature (Fig. 1c). The TEM images in Fig. 1d–f present 3D interconnected porous structures of EBCs. Notably, the pore size in EBC800 (Fig. 1e) is larger than that in EBC750 (Fig. 1d). EBC850 exhibits ultrathin architectures due to the tailor function of K2CO3 at higher temperatures (Fig. 1f). The HRTEM image of EBC800 shows that EBC800 features local graphitization with a thickness of only ca. 6.5 nm (Fig. S1). The energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS) mapping images of EBC800 (Fig. 1g) display a relatively homogeneous distribution of C, N, and O elements, which confirm that N and O atoms were successfully doped in EBCs.

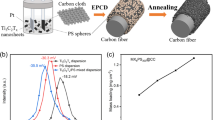

The nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms of three EBC samples are shown in Fig. 2a. All of the isotherms display hierarchical pore structures, e.g., typical IV-type curves with strong adsorption at P/P0 < 0.01 and small hysteresis loops at 0.4 < P/P0 < 0.95, which indicates the coexistence of micropores and mesopores. The micropores can be functioned as ion-adsorption active sites, while mesopores provide channels for ion fast transport [27]. The pore size of most of the EBC samples is less than 3 nm due to the in situ activation role of K2CO3 (Fig. 2b). SBET of EBCs increases from 604 to 854 m2 g−1 and then decreases to 834 m2 g−1 when the heat treatment temperature increases from 750 to 850 °C, while Dap of the EBC samples increases from 2.27 to 2.43 nm (Table 1). The yields of EBC750, EBC800 and EBC850 are 34.27%, 22.78%, and 16.55%, respectively. The foregoing results suggest that the pore structure parameters and yields of EBCs are easily tuned by changing the heat treatment temperatures.

The XRD patterns of EBCs only present the (002) and (100) peaks at ca. 25° and 43° (Fig. 2c). The d002 decreases from 0.3576 nm for EBC750 to 0.3515 nm for EBC850, while Lc increases from 1.1574 to 1.2417 nm, which reveals that the graphitization degree and crystallite height increases with an increase in the heat treatment temperature from 750 to 850 °C (Table S1). The Raman spectra display a typical D-band and G-band of carbonaceous materials (Fig. 2d). The D-band located at ca. 1344 cm−1 is related to the defects and disorder structures [28], while the G-band at ca. 1592 cm−1 can be assigned to the graphitic structures [29]. The peak intensity ratio of the D-band to G-band (ID/IG) of EBC850 (0.94) is lower than that of EBC750 (0.98) and EBC800 (0.96), which suggests that EBC850 possesses the highest graphitization degree among the three samples, which is consistent with the XRD results. The electrical conductivity of EBC800 is 508 S m−1, which is higher than that of EBC750 (84 S m−1) and EBC850 (242 S m−1), and higher than that of the interconnected carbon nanosheet (226 S m−1) [30]. The survey XPS spectra (Fig. 2e) of the three samples only present two strong peaks at 284.9 and 532.4 eV and present a weak peak at 399.8 eV, which corresponds to the peaks of C 1s, O 1s, and N 1s, respectively. The XRD and XPS results indicate that the impurities can be removed by using water washing, that is, this synthesis route avoids the acid washing step, simplifies the preparation process and reduces the cost. The O 1s spectra of the EBC samples were deconvoluted into two peaks: C=O (532.1 eV) and C–O (533.3 eV) (Fig. S2a–c) [31]. The N 1s spectra of EBCs can be fitted into four peaks, which correspond to pyridinic N (N-6, 398.8 eV), pyrrolic N (N-5, 400.3 eV), quaternary N (N-Q, 401.3 eV), and oxidized pyridinic N (N-X, 403.4 eV) groups (Figs. 2f and S2d, e) [32]. The maximum O and N contents in EBC800 are 8.21 and 3.55 at%, respectively (Table S2), which shows agreement with the element analysis results (Table S3). The N-5 and N-6 contributed to the pseudocapacitive interactions, which improved the capacitance. The N-Q and N-X can effectively facilitate electron transfer, which enhances the conductivity of carbon materials [6]. Figure S3 exhibits the FTIR spectra of the EBC samples. All of the EBC samples present absorption peaks at ca. 1080, 1387, and 1625 cm−1, which correspond to stretching vibrations of C=O, C–N, and C–O [33], respectively, which is consistent with the results of the XPS analysis. The water contact angle of EBC750, EBC800, and EBC850 is 19.1°, 18.6°, and 39.4°, respectively (Fig. S4), which is obviously lower than that of porous carbon nanosheets (84°–127°), indicates that the residual O functionalities greatly improve the wettability of EBCs [14].

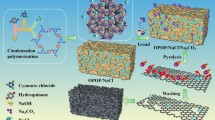

The synthetic scheme of EBCs from CTP is shown in Fig. 3. CTP and K2CO3 were mixed in the solid state and then distributed on the surface of the carbon cloth. Subsequently, during the heating process, the liquefied CTP diffused and coated onto the surfaces of the K2CO3 particles and carbon cloth to form 3D interconnected films. As the heat treatment temperature gradually increased to 600 °C, K2CO3 started to react with carbon as follows: K2CO3 + 2C → 2K + 3CO [28]. Carbon cloth served as a template to direct the transformation of aromatic hydrocarbon molecules in the CTP into EBCs. Benefiting from the synergetic effect of the in situ tailor/activation of K2CO3 and the directing function of the carbon cloth, EBCs with hierarchical pores and egg-box-like structures are generated simultaneously. By simply washing with deionized water, the final product of 3D N,O-codoped EBCs with opened pores in pores is achieved.

Figure 4 shows the schematic of the ion transport and electron conduction in 3D EBC electrodes. The 3D interconnected structures offer highways for electron conduction, which enables superior cycle stability. On the other hand, the pore-in-pore structures provide short channels for fast ion transport, which yields a satisfactory rate performance and high areal capacitance. According to formula [34],

where τ0, q, D, and L are the time constants, a dimensionality-dependent constant (q = 2, 4, or 6 for one-dimensional diffusion, two-dimensional diffusion, or three-dimensional diffusion, respectively), diffusion coefficient, diffusion distance, respectively, the ion diffusion time in 3D EBC electrodes is shorter than that in 1D and 2D materials, which enables a better rate capability.

3.2 Electrochemical Performance

Benefiting from the 3D egg-box-like structures with opened pores in pores, high mesopore content, and moderate N, O doping level, the as-obtained EBC samples are expected to be ideal electrode materials for SCs. The electrochemical performance of the EBC samples was tested by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) measurements using a three-electrode system in 6 M KOH electrolyte. For the Hg/HgO electrode, platinum foil was employed as the reference and counter electrode, respectively. The areal loading of active material on each EBC electrode is ca. 2.12 mg cm−2. At the scan rate of 5 mV s−1, the CV curves (Fig. 5a) of the EBC electrodes exhibit a quasi-rectangular shape with redox humps. The GCD curves (Fig. 5b) of the EBC electrodes at 0.212 mA cm−2 show linear shapes with a slight deviation from the line. The deviation of both the CV and GCD curves reveal the presence of pseudocapacitance caused by the faradaic reaction of the N and O functionalities. The areal capacitance is 37.0 μF cm−2 (223 F g−1), 39.8 μF cm−2 (340 F g−1), and 29.5 μF cm−2 (246 F g−1) for EBC750, EBC800, and EBC850, respectively, at the current density of 0.106 mA cm−2 (Fig. 5c). The EBC800 electrode achieves a high areal capacitance to 29.6 μF cm−2 (253 F g−1) at 10.6 mA cm−2 and maintains 26.0 μF cm−2 (222 F g−1) at 42.4 mA cm−2.

The electrochemical kinetic of EBCs was investigated to understand the nature of the charge storage mechanism and contribution of N,O-containing functional groups on pseudocapacitance. Generally, the capacitance (C) can be calculated via the following equation: \(C = k_{1} + k_{2} t^{1/2}\), where k1, k2t1/2, t represents the surface capacitive effects (CE, related to the EDLC), diffusion controlled process (CP, ascribed to pseudocapacitance) and discharge time, respectively [35]. The k1 and k2 for EBC750 are 155.03 and 1.16, respectively, while that for EBC800 is 242.35 and 1.39, respectively, and that for EBC850 is 159.62 and 1.35, respectively (Fig. 5d). For EBC800, the contribution of CP on C decreases as the current density increases. The CE and CP values of EBC800 electrode are higher than that of EBC750 and EBC850 electrodes at the same current density. At 0.106 mA cm−2, among the three EBC electrodes, EBC800 presents the highest CE of 242.4 F g−1 due to its largest SBET and presents the highest CP of 97.3 F g−1 due to its highest total content of O and N heteroatom (11.76 at %), as shown in Table S2.

The electrochemical performance of EBC electrodes is evaluated in the symmetric coin-type SCs in 6 M KOH electrolyte. The GCD curves of EBCs present symmetrical shapes (Fig. 6a), which suggest the ideal electric double layer capacitor (EDLC) behavior. The IR drop of EBC750, EBC800, and EBC850 is only 0.00262, 0.00143, and 0.00257 V, respectively, which confirms the excellent electric conductivity of EBCs [36]. At the current density of 0.1075 mA cm−2, the areal capacitance of EBC750, EBC800 and EBC850 is 23.0 μF cm−2 (139 F g−1), 27.6 μF cm−2 (236 F g−1) and 19.0 μF cm−2 (159 F g−1), respectively (Figs. 6b and S5). Even at a very high current density of 215 mA cm−2, the areal capacitance of EBC800 can be retained at 18.8 μF cm−2 (160 F g−1), while for EBC750 and EBC850, the areal capacitance is 12.0 and 15.8 μF cm−2, respectively. Although the difference between EBC800 and EBC850 in SBET is small, the areal capacitance of EBC800 is higher than that of EBC850, which is due to the higher content of N, O heteroatom. The gravimetric and areal capacitance of EBC800 at the current density of 0.1075–215 mA cm−2 is the highest due to the largest SBET of EBC800 and the optimal O content among the three samples. The areal capacitance of EBC800 is also higher than those of carbon-based electrodes reported in the literature (as summarized in Table 2) [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. The high capacitance and excellent rate capability of EBCs are ascribed to its 3D interconnected egg-box-like structures with opened pores in pores, which provide plentiful channels for ion fast transport, abundant active sites for ion adsorption and highways for electron conduction [49]. Moreover, the oxygen-containing groups are conducive to boosting the surface wettability of the EBC electrodes in KOH electrolyte. Furthermore, the moderate N-containing functional groups are beneficial to provide pseudocapacitance, which causes high capacitance. A long cycle life is another key factor for the practical application of SCs. The maximum capacitance retention of EBC800-based SC is 98.1% even after 50,000 cycles at 10.75 mA cm−2 (Fig. 6c), which exhibits a long-term cycle stability. Additionally, the EBC800-based SC displays a high coulombic efficiency of 109.7% after 50,000 cycles, which implies excellent reversibility. This finding proves that the EBC800-based SC can be used as a long-life energy storage device. In addition, the energy density of the EBC800 capacitor is 0.01763 mWh cm−2 at the power density of 0.056 mW cm−2 (Fig. 6d), which confirms its potential application.

a GCD curves of EBC electrodes at 1 A g−1. b Areal capacitance of EBC electrodes at various current densities. c Capacitance retention and coulombic efficiency of EBC800-based SC after 50,000 cycles at 10.75 mA cm−2. d Ragone plots of EBC capacitors. e Nyquist plots of EBC electrodes. f Bode plots of phase angle versus frequency

The CV curves of EBC electrodes show a rectangular shape at the scan rate of 2 mV s−1 (Fig. S6a–c). No obvious distortions in the CV curves are observed when the scan rate increases to 200 mV s−1, which exhibits the ion fast transport within electrodes and satisfactory rate capability (Fig. S6d). The Nyquist plots of EBC electrodes are composed of a straight line in the low frequency region and a semicircle in the high-frequency region (Fig. 6e), and the corresponding electric equivalent circuit model is displayed in Fig. S7. The straight line in the low frequency region exhibits ideal capacitive behavior [21]. The x-intercept of the Z′ axis corresponds to the intrinsic ohmic resistance (Rs) of EBC electrodes, while the diameter of the semicircle represents the charge transfer resistance (Rct) [50]. The short x-intercept and small diameter of a semicircle prove that the EBC800 electrode has low internal resistance and charge transfer resistance due to its novel 3D interconnected N,O-codoped egg-box-like structures with opened pores in pores to provide channels for ion transport and electron conduction. In the Bode plots, the phase angle of EBC750, EBC800 and EBC850 is − 87.2°, − 87.6°, and − 87.2°, respectively, at 0.001 Hz, which indicates the excellent EDLC behavior [51]. The characteristic frequency (f0) at the phase angle of − 45° for EBC750, EBC800, and EBC850 is 0.42, 1.14, and 0.76 Hz, respectively, which correspond to the relaxation time (τ0, τ0 = 1/f0) of only 2.38, 0.88, and 1.32 s, respectively (Fig. 6f), which confirms the best charge/discharge rate of EBC800 among the three EBC samples [52, 53].

The all-solid-state SC with a symmetric two-electrode configuration was also fabricated based on the EBC800 electrode and KOH/PVA gel polymer electrolyte to further ascertain the electrochemical performance of the EBC samples (Fig. S8). The CV curves of EBC800 at various scan rates exhibit a quasi-rectangular shape, which suggests a satisfactory capacitive behavior (Fig. S8a). The GCD curve of EBC800 presents an approximately symmetric triangular-shape at the current density of 0.218 mA cm−2 (Fig. S8b). At the current density of 0.109 mA cm−2, the areal capacitance of EBC800 is 25.0 μF cm−2, which corresponds to the gravimetric capacitance of 214 F g−1, and the areal capacitance of EBC800 remains 15.2 μF cm−2 (130 F g−1) at 43.6 mA cm−2 with a capacitance retention of 60.5% (Fig. S8c). The gravimetric capacitance of the all-solid-state SC based on EBC800 electrode is higher than those of the reported carbonaceous electrodes, e.g., hierarchically graphene nanocomposite (180 F g−1) [54], activated carbon/carbon nanotube/reduced graphene oxide film (101 F g−1) [33], waste sugar-based carbon materials (105 F g−1) [55], and 3D graphene hydrogel film (186 F g−1) [56]. The capacitance retention of the EBC800-based all-solid-state SC is 96.1% after 10,000 cycles at 10.9 mA cm−2, which also display excellent cycle stability (Fig. S8d). In addition, the EBC800-based all-solid-state SC presents a high coulombic efficiency of 98.5% after 10,000 cycles. The EBC800 capacitor shows a high energy density of 0.0233 mWh cm−2 at the power density of 0.0979 mW cm−2 (Fig. S8e). The Rs of EBC800 electrode is only 1.35 Ohm, as shown in Fig. S8f. Moreover, the negligible semicircle in the high-frequency region also proves a low Rct of EBC800 sample. EBCs hold a potential application in SCs, as evidenced by their high areal capacitance, excellent rate capability and long-term cycle stability in aqueous and all-solid-state SCs. The satisfactory electrochemical performance of the EBC800 electrode is explained as follows: (1) the pore-in-pore structures offer short channels for fast ion transport, which yields excellent rate performance and high areal capacitance; (2) the 3D interconnected networks provide highways for electron conduction, which produces superior cycle stability; (3) the oxygen-containing groups are conducive to boosting the surface wettability of the EBC800 electrode in KOH electrolyte; (4) the N, O functionalities are beneficial for providing pseudocapacitance, which delivers a high capacitance.

4 Conclusion

For the first time, a less harmful route was reported in this paper to prepare 3D N,O-codoped EBCs from CTP for SC application. This route avoids the acid washing step, simplifies the process and reduces the cost. Benefiting from the 3D interconnected egg-box-like structures with opened pores in pores and N,O-containing functional groups, the EBCs exhibit a prominent areal capacitance of 39.8 μF cm−2 at 0.106 mA cm−2 in aqueous electrolyte. Furthermore, as an electrode for SC, EBC presents a high areal capacitance of 27.6 μF cm−2 at 0.1075 mA cm−2 and a long-term cycle stability with only 1.9% decay after 50,000 cycles. In addition, the EBC electrode shows a high areal capacitance of 25.0 μF cm−2 and an energy density of 0.0233 mWh cm−2 even in all-solid-state SCs. This work provides an acid-free process for the synthesis of carbon-based electrode materials from industrial residual pitch-based carbon sources for long-life energy storage devices.

References

Z. Bo, C.W. Li, H.C. Yang, K. Ostrikov, J.H. Yan, K.F. Cen, Design of supercapacitor electrodes using molecular dynamics simulations. Nano-Micro Lett. 10, 33 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-018-0188-2

C.G. Hu, Y. Lin, J.W. Connell, H.-M. Cheng, Y. Gogotsi, M.-M. Titirici, L.M. Dai, Carbon-based metal-free catalysts for energy storage and environmental remediation. Adv. Mater. 31, 1806128 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201806128

T. Zhai, S. Sun, X.J. Liu, C.L. Liang, G.M. Wang, H. Xia, Achieving insertion-like capacity at ultrahigh rate via tunable surface pseudocapacitance. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706640 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201706640

Z.F. Yang, J.R. Tian, Z.F. Yin, C.J. Cui, W.Z. Qian, F. Wei, Carbon nanotube- and graphene-based nanomaterials and applications in high-voltage supercapacitor: a review. Carbon 141, 467–480 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2018.10.010

X.L. Zhao, B.N. Zheng, T.Q. Huang, C. Gao, Graphene-based single fiber supercapacitor with a coaxial structure. Nanoscale 7, 9399–9404 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/c5nr01737h

B.B. Chang, W.W. Shi, S.C. Han, Y.N. Zhou, Y.X. Liu, S.R. Zhang, B.C. Yang, N-rich porous carbons with a high graphitization degree and multiscale pore network for boosting high-rate supercapacitor with ultrafast charging. Chem. Eng. J. 350, 585–598 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.06.013

Z.S. Li, L. Zhang, X. Chen, B.L. Li, H.Q. Wang, Q.Y. Li, Three-dimensional graphene-like porous carbon nanosheets derived from molecular precursor for high-performance supercapacitor application. Electrochim. Acta 296, 8–17 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2018.11.002

H. Palneedi, J.H. Park, D. Maurya, M. Peddigari, G.T. Hwang et al., Laser irradiation of metal oxide films and nanostructures: applications and advances. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705148 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201705148

Q.F. Meng, K.F. Cai, Y.X. Chen, L.D. Chen, Research progress on conducting polymer based supercapacitor electrode materials. Nano Energy 36, 268–285 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2017.04.040

L.L. Zhang, D. Huang, N.T. Hu, C. Yang, M. Li et al., Three-dimensional structures of graphene/polyaniline hybrid films constructed by steamed water for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 342, 1–8 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.11.068

L.H. Tseng, C.H. Hsiao, D.D. Nguyen, P.Y. Hsieh, C.Y. Lee, N.H. Tai, Activated carbon sandwiched manganese dioxide/graphene ternary composites for supercapacitor electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 266, 284–292 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2018.02.029

U. Balasubramani, R. Venkatesh, S. Subramaniam, G. Gopalakrishnan, V. Sundararajan, Alumina/activated carbon nano-composites: synthesis and application in sulphide ion removal from water. J. Hazard. Mater. 340, 241–252 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.07.006

B. Xu, H.R. Wang, Q.Z. Zhu, N. Sun, B. Anasori et al., Reduced graphene oxide as a multi-functional conductive binder for supercapacitor electrodes. Energy Storage Mater. 12, 128–136 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2017.12.006

M.Y. Liu, J. Niu, Z.P. Zhang, M.L. Dou, F. Wang, Potassium compound-assistant synthesis of multi-heteroatom doped ultrathin porous carbon nanosheets for high performance supercapacitors. Nano Energy 51, 366–372 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.06.037

L. Peng, Y.J. Cai, Y. Luo, G. Yuan, J.Y. Huang et al., Bioinspired highly crumpled porous carbons with multidirectional porosity for high rate performance electrochemical supercapacitors. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 12716–12726 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b01839

Y. Zhang, Q.T. Ma, H. Li, Y.W. Yang, J.Y. Luo, Robust production of ultrahigh surface area carbon sheets for energy storage. Small 14, 1800133 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201800133

S.H. Zheng, Z.S. Wu, S. Wang, H. Xiao, F. Zhou, C.L. Sun, X.H. Bao, H.M. Cheng, Graphene-based materials for high-voltage and high-energy asymmetric supercapacitors. Energy Storage Mater. 6, 70–97 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2016.10.003

Z.P. Qiu, Y.S. Wang, X. Bi, T. Zhou, J. Zhou et al., Biochar-based carbons with hierarchical micro-meso-macro porosity for high rate and long cycle life supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 376, 82–90 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.11.077

Y. Liu, Z.R. Wang, W. Teng, H.W. Zhu, J.X. Wang et al., A template-catalyzed in situ polymerization and co-assembly strategy for rich nitrogen-doped mesoporous carbon. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 3162–3170 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/c7ta10106f

M. Zhang, M. Chen, N. Reddeppa, D.L. Xu, Q.S. Jing, R.H. Zha, Nitrogen self-doped carbon aerogels derived from trifunctional benzoxazine monomers as ultralight supercapacitor electrodes. Nanoscale 10, 6549–6557 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/c8nr00207j

J.S. Zhou, L. Hou, S.R. Luan, J.L. Zhu, H.Y. Gou, D. Wang, F.M. Gao, Nitrogen codoped unique carbon with 0.4 nm ultra-micropores for ultrahigh areal capacitance supercapacitors. Small 14, 1801897 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201801897

S. Zhang, K. Tian, B.-H. Cheng, H. Jiang, Preparation of N-doped supercapacitor materials by integrated salt templating and silicon hard templating by pyrolysis of biomass wastes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 5, 6682–6691 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b00920

C.L. Han, S.P. Wang, J. Wang, M.M. Li, J. Deng, H.R. Li, Y. Wang, Controlled synthesis of sustainable N-doped hollow core-mesoporous shell carbonaceous nanospheres from biomass. Nano Res. 7, 1809–1819 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12274-014-0540-x

J. Zhang, K. Anderson, D. Britt, Y. Liang, Sustaining biogenic methane release from Illinois coal in a fermentor for one year. Fuel 227, 27–34 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2018.04.061

J.W. Qi, B.L. Jin, P.Y. Bai, W.D. Zhang, L. Xu, Template-free preparation of anthracite-based nitrogen-doped porous carbons for high-performance supercapacitors and efficient electrocatalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction. RSC Adv. 9, 24344–24356 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C9RA04791C

L. Li, J.B. Zhang, Z.W. Peng, Y.L. Li, C. Gao et al., High-performance pseudocapacitive microsupercapacitors from laser-induced graphene. Adv. Mater. 28, 838–845 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201503333

J.L. Blackburn, A.J. Ferguson, C. Cho, J.C. Grunlan, Carbon-nanotube-based thermoelectric materials and devices. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704386 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201704386

J.S. Xia, N. Zhang, S.K. Chong, D. Li, Y. Chen, C.H. Sun, Three-dimensional porous graphene-like sheets synthesized from biocarbon via low-temperature graphitization for a supercapacitor. Green Chem. 20, 694–700 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/c7gc03426a

T. Lv, M.X. Liu, D.Z. Zhu, L.H. Gan, T. Chen, Nanocarbon-based materials for flexible all-solid-state supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705489 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201705489

H.L. Wang, Z.W. Xu, A. Kohandehghan, Z. Li, K. Cui et al., Interconnected carbon nanosheets derived from hemp for ultrafast supercapacitors with high energy. ACS Nano 7, 5131–5141 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1021/nn400731g

T.Q. Lin, I.-W. Chen, F.X. Liu, C.Y. Yang, H. Bi, F.F. Xu, F.Q. Huang, Nitrogen-doped mesoporous carbon of extraordinary capacitance for electrochemical energy storage. Science 350, 1508–1513 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab3798

Q.L. Zhu, P. Pachfule, P. Strubel, Z.P. Li, R.Q. Zou, Z. Liu, S. Kaskel, Q. Xu, Fabrication of nitrogen and sulfur co-doped hollow cellular carbon nanocapsules as efficient electrode materials for energy storage. Energy Storage Mater. 13, 72–79 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2017.12.027

X. Li, Y. Tang, J.H. Song, W. Yang, M.S. Wang et al., Self-supporting activated carbon/carbon nanotube/reduced graphene oxide flexible electrode for high performance supercapacitor. Carbon 129, 236–244 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2017.11.099

T. Liu, F. Zhang, Y. Song, Y. Li, Recent advances in chemical methods for activating carbon and metal oxide based electrodes for supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 17151–17173 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/c7ta05003h

Z.Y. Song, D.Z. Zhu, L.C. Li, T. Chen, H. Duan et al., Ultrahigh energy density of a N, O codoped carbon nanosphere based all-solid-state symmetric supercapacitor. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 1177–1186 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/c8ta10158b

C.C. Liu, X.J. Yan, F. Hu, G.H. Gao, G.M. Wu, X.W. Yang, Toward superior capacitive energy storage: recent advances in pore engineering for dense electrodes. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705713 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201705713

F. Sun, Z.B. Qu, J.H. Gao, H.B. Wu, F. Liu et al., In situ doping boron atoms into porous carbon nanoparticles with increased oxygen graft enhances both affinity and durability toward electrolyte for greatly improved supercapacitive performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 180419 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201804190

Y.F. Bu, T. Sun, Y.J. Cai, L.Y. Du, O. Zhuo et al., Compressing carbon nanocages by capillarity for optimizing porous structures toward ultrahigh-volumetric-performance supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 29, 1700470 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201700470

N.N. Guo, M. Li, Y. Wang, X.K. Sun, F. Wang, R. Yang, Soybean root-derived hierarchical porous carbon as electrode material for high-performance supercapacitors in ionic liquids. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 33626–33634 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b11162

L. Yao, Q. Wu, P.X. Zhang, J.M. Zhang, D.R. Wang et al., Scalable 2D hierarchical porous carbon nanosheets for flexible supercapacitors with ultrahigh energy density. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706054 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201706054

L. Zhi, T. Li, H. Yu, S.B. Chen, L.Q. Dang et al., Hierarchical graphene network sandwiched by a thin carbon layer for capacitive energy storage. Carbon 113, 100–107 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2016.11.036

J. Zhao, Y.F. Jiang, H. Fan, M. Liu, O. Zhuo et al., Porous 3D few-layer graphene-like carbon for ultrahigh-power supercapacitors with well-defined structure-performance relationship. Adv. Mater. 29, 1604569 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201604569

J.-G. Wang, H.Z. Liu, X.Y. Zhang, X. Li, X.R. Liu, F.Y. Kang, Green synthesis of hierarchically porous carbon nanotubes as advanced materials for high-efficient energy storage. Small 14, 1703950 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201703950

D. Puthusseri, V. Aravindan, S. Madhavi, S. Ogale, 3D micro-porous conducting carbon beehive by single step polymer carbonization for high performance supercapacitors: the magic of in situ porogen formation. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 728–735 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1039/c3ee42551g

J.Z. Chen, J.L. Xu, S. Zhou, N. Zhao, C.P. Wong, Nitrogen-doped hierarchically porous carbon foam: a free-standing electrode and mechanical support for high-performance supercapacitors. Nano Energy 25, 193–202 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.04.037

Y.S. Yun, S. Lee, N.R. Kim, M. Kang, C. Leal, K.Y. Park, K. Kang, H.J. Jin, High and rapid alkali cation storage in ultramicroporous carbonaceous materials. J. Power Sources 313, 142–151 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.02.068

H.R. An, Y. Li, P. Long, Y. Gao, C.Q. Qin, C. Cao, Y.Y. Feng, W. Feng, Hydrothermal preparation of fluorinated graphene hydrogel for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 312, 146–155 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.02.057

M. Wahid, G. Parte, D. Phase, S. Ogale, Yogurt: a novel precursor for heavily nitrogen doped supercapacitor carbon. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 1208–1215 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/c4ta06068g

M.R. Benzigar, S.N. Talapaneni, S. Joseph, K. Ramadass, G. Singh et al., Recent advances in functionalized micro and mesoporous carbon materials: synthesis and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 2680–2721 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/c7cs00787f

F. Yang, S.K. Zhang, Y. Yang, W. Liu, M.N. Qiu, Y. Abbas, Z.P. Wu, D.Z. Wu, Heteroatoms doped carbons derived from crosslinked polyphosphazenes for supercapacitor electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 328, 135064 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2019.135064

H.Y. Wang, J. Deng, C.M. Xu, Y.Q. Chen, F. Xu, J. Wang, Y. Wang, Ultramicroporous carbon cloth for flexible energy storage with high areal capacitance. Energy Storage Mater. 7, 216–221 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2017.03.002

H. Ye, S. Xin, Y.X. Yin, Y.G. Guo, Advanced porous carbon materials for high-efficient lithium metal anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1700530 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201700530

S.Y. Lu, M. Jin, Y. Zhang, Y.B. Niu, J.C. Gao, C.M. Li, Chemically exfoliating biomass into a graphene-like porous active carbon with rational pore structure, good conductivity, and large surface area for high-performance supercapacitors. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1702545 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201702545

L.X. Feng, K. Wang, X. Zhang, X.Z. Sun, C. Li, X.B. Ge, Y.W. Ma, Flexible solid-state supercapacitors with enhanced performance from hierarchically graphene nanocomposite electrodes and ionic liquid incorporated gel polymer electrolyte. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1704463 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201704463

A. Mahto, R. Gupta, K.K. Ghara, D.N. Srivastava, P. Maiti et al., Development of high-performance supercapacitor electrode derived from sugar industry spent wash waste. J. Hazard. Mater. 340, 189–201 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.06.048

Y.X. Xu, Z.Y. Lin, X.Q. Huang, Y. Liu, Y. Huang, X.F. Duan, Flexible solid-state supercapacitors based on three-dimensional graphene hydrogel films. ACS Nano 7, 4042–4049 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1021/nn4000836

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the funding support of this work by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. U1710116, U1508201 and 51872005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, F., He, X., Ma, L. et al. 3D N,O-Codoped Egg-Box-Like Carbons with Tuned Channels for High Areal Capacitance Supercapacitors. Nano-Micro Lett. 12, 82 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00416-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00416-2