Abstract

Metal halide perovskite solar cells (PSCs) have attracted extensive research interest for next-generation solution-processed photovoltaic devices because of their high solar-to-electric power conversion efficiency (PCE) and low fabrication cost. Although the world’s best PSC successfully achieves a considerable PCE of over 20% within a very limited timeframe after intensive efforts, the stability, high cost, and up-scaling of PSCs still remain issues. Recently, inorganic perovskite material, CsPbBr3, is emerging as a promising photo-sensitizer with excellent durability and thermal stability, but the efficiency is still embarrassing. In this work, we intend to address these issues by exploiting CsPbBr3 as light absorber, accompanied by using Cu-phthalocyanine (CuPc) as hole transport material (HTM) and carbon as counter electrode. The optimal device acquires a decent PCE of 6.21%, over 60% higher than those of the HTM-free devices. The systematic characterization and analysis reveal a more effective charge transfer process and a suppressed charge recombination in PSCs after introducing CuPc as hole transfer layer. More importantly, our devices exhibit an outstanding durability and a promising thermal stability, making it rather meaningful in future fabrication and application of PSCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Highlights

-

Cu-phthalocyanine was employed as hole transport material for CsPbBr3 inorganic perovskite solar cells.

-

The optimal device acquires a decent power conversion efficiency of 6.21%, over 60% higher than those of the hole transport material-free devices.

-

The device exhibits an outstanding durability and a promising thermal stability.

2 Introduction

Organic–inorganic perovskite solar cells (PSCs) are appearing as a hopeful new generation of photovoltaic technology and have revolutionized the prospects of emerging photovoltaic industry, because of the tremendous increase in device performance [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The outstanding photoelectric properties, such as high absorption coefficient, suitable and adjustable band gap [7,8,9], ambipolar charge transport [10,11,12,13], and long carrier diffusion length [14, 15], make perovskite materials very appropriate for light harvesting in photovoltaics. Since the breaking report from Miyasaka [16], power conversion efficiency (PCE) of such PSCs has reached a remarkable value (over 22%) in a short span [17,18,19], approaching the efficiency of commercialized c-Si solar cells and thin-film photovoltaic solar cells such as CdTe and Cu2ZnSn(Se,S)4 [20]. Despite the rapid increment in PCE associated with the evolution of new perovskite materials and novel fabrication techniques, the instability of PSCs remains unresolved. The mostly studied hybrid perovskite materials, for example methylammonium lead triiodide (MAPbI3) and formamidinium lead triiodide (FAPbI3), are forceless against moisture and heat. Some organic additives in commonly used HTMs, such as lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) and tert-butylpyridine (tBP), are also hygroscopic and deliquescent, accelerating performance degradation [21,22,23,24]. Thus, precise environmental controls (gloveboxes or dryrooms) are often necessary during the fabrication of organic–inorganic hybrid PSCs. On the other side, efficient PSCs generally employ a p-type organic small-molecule or polymeric hole conductor, such as 2,2′,7,7′-tetrakis (N,N′-di-p-methoxyphenylamine)-9,9′-spirobifluorene (spiro-OMeTAD) [25], poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) [26], and poly(triarylamine) (PTAA) [27] as hole-extraction materials to boost device efficiencies. Discouragingly, these conventional HTMs suffer from disadvantages of high synthetic cost, thermal and chemical instability, and low hole mobility or low conductivity in their pristine form [28,29,30], seriously hindering the viable commercialization of the emerging PSC technology. The necessary doping techniques involved in improving their carrier density and conductivity further increase the cost in production. In addition, the high-energy-consuming coating process together with the consumption of noble metals as counter electrode (such as Au and Ag, widely used in efficient state-of-the-art PSCs) gives another problem for the commercialization of PSCs. To sum up, there are mainly three cruxes for the future up-scaling of PSCs: (1) exploring novel perovskite materials and HTMs with high stability against humidity and heat; (2) developing efficient, low-cost, durable, and scalable alternative HTMs that can replace currently used organic ones; (3) searching for low-cost and scalable substitutions for noble counter electrodes.

It has been proposed that inorganic perovskites (e.g., CsPbI3 and CsPbBr3) are more stable than organic ones, due to smaller ionic radius of Cs+ than those of FA+ and MA+ cations. Many works on PSCs with inorganic perovskites as light absorber have been reported. Tan et al. [31] incorporated Cs+ into MA/FA hybrid perovskite to improve the photostability of solar cells. Luo et al. [32] prepared a CsPbI3 HTM-based PSC under fully open-air conditions with a PCE of 4.13%. Kulbak et al. [33] reported CsPbBr3 PSCs with different HTMs and achieved a highest PCE of 6.2%. Sutton et al. [34] demonstrated a CsPbI2Br-based inorganic mixed halide PSC with an efficiency up to 9.8% and high ambient stability. Both Chen’s group and Liu’s group proposed a kind of carbon-based CsPbBr3 all-inorganic PSCs and achieved optimal efficiencies of 5.0% [35] and 6.7% [36], respectively. All these PSCs using inorganic perovskite have demonstrated a relatively enhanced stability. On the other hand, p-type semiconductor CuPc, small molecular HTMs with planar configuration, is preferable in fabricating stable and efficient traditional organic PSCs [37,38,39]. It owns properties of low cost, ease of synthesis, low band gap, high hole mobility of 10−3–10−2 cm2 V−1 S−1 (as compared with 4 × 10−5 cm2 V−1 S−1 for spiro-OMeTAD) [40], good stability (starting degradation above 500 °C in air), and long exciton diffusion length (Lex ranging from 8 to 68 nm) [41,42,43]. Nonetheless, CuPc is never reported as HTM in inorganic perovskite photovoltaic devices. Besides, novel counter electrodes including Al [44], Ni [45], and carbon [46,47,48] have been explored in PSCs recently. Among them, carbon is thought to be the most promising for the electrode material because carbon is cheap, stable, inert to ion migration originating from perovskite and metal electrodes, inherently water-resistant, and therefore advantageous for good stability. The emergence of carbon counter electrode-based PSCs greatly lowers the cost and simplifies the procedures, rolling forward the development and commercialization of PSCs [49].

In this work, CuPc were introduced as HTM in carbon counter electrode-based CsPbBr3 inorganic PSCs. For comparison, HTM-free PSCs were also made as the control devices. The optimal CuPc-based device performance with an efficiency of 6.21% has been achieved, 63% higher than the HTM-free device. Systematic characterization and analysis were performed to reveal the underlying mechanism of the improvement originated from the CuPc HTM layer. Our results suggest that introducing CuPc between the perovskite layer and carbon electrode provides a simple and effective route to facilitate charge transfer and suppress charge recombination in PSCs. More importantly, our devices exhibit an outstanding durability and a promising thermal stability, compared with the HTM-free CsPbBr3 devices and traditional MAPbI3 devices.

3 Experimental Section

3.1 Synthesis of Carbon Paste

One gram polyvinyl acetate (PVAc) and 0.5 g hydroxypropyl cellulose were dissolved in 60 mL ethyl acetate. PVAc acted as the binder in the carbon film, and hydroxypropyl cellulose was used to adjust the viscosity of the carbon paste. 20 mL of the mixed ethyl acetate solution was blended with 2 g 40-nm graphite powder, 1 g 10-μm flake graphite, 1 g 40-nm carbon black, and 0.5 g 50-nm ZrO2 powder. The ZrO2 particles were introduced to enhance the scratch resistance performance of the carbon film [50, 51]. After vigorously milling for 2 h in an electro-mill (QM-QX0.4, Instrument Factory of Nanjing University), the printable carbon paste was ready.

3.2 Device Fabrication

Perovskite thin film and solar cells were fabricated on fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO)-glass substrate with the sheet resistance of 14 Ω sq−1. Diluted hydrochloric acid (2 mol L−1) and zinc powder were used to pattern the fluorine-doped tin oxide substrates. After ultrasonically cleaned by acetone, ethanol, and deionized (DI) water, the FTO substrates were treated under oxygen plasma for 30 min to remove the last traces of organic residues. A thin layer of compact anatase TiO2 with 50 nm in thickness was deposited by spin-coating a mildly acidic solution of titanium isopropoxide in ethanol at 5000 rpm for 60 s and consequently annealed at 500 °C for 30 min. After cooling down to room temperature, the mesoporous TiO2 scaffold (particle size 20 nm) was formed by spin-coating TiO2 paste (DSL. 18NR-T, 20 nm, Dyesol, Australia) diluted in ethanol (2:7 weight ratio) at 5000 rpm for 60 s and consequently heating at 500 °C for 30 min. The CsPbBr3 perovskite layer was prepared by a sequential method. 1.47 g PbBr2 was dissolved in 4 mL N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and heated at 80 °C for 12 h under magnetic stirring. The prepared mesoporous TiO2 films were preheated to ~ 80 °C and then infiltrated with the PbBr2 precursor solution by spin-coating at 2000 rpm for 45 s and dried at 80 °C for 30 min immediately. Sequentially, the PbBr2 films were immersed in a methanol solution of 0.07 M CsBr for 15 min. After rinsed by 2-propanol and dried in air, the samples were heated to 250 °C for 5 min on a hotplate to form a uniform layer of CsPbBr3. CuPc was deposited on the perovskite film by vacuum evaporation (< 1 × 10−3 Pa) using quartz crystal monitor to determine the thickness and deposition rate. The deposition of carbon CE was conducted by doctor blade method and dried at 80 °C for 15 min. All these procedures were carried out on naturally ambient atmosphere.

3.3 Characterization

The morphology of the perovskite surface and cross-sectional structure of the solar cells was observed by the field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, JSM-7600F, JEOL). The formation of CsPbBr3 perovskite absorber layer has been further confirmed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (PANalytical PW3040/60) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) from 10° to 50°. An X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS, Axis Ultra DLD, Shimadzu) equipped with a monochromatic Al Kα source (1486.6 eV) was employed to determine the surface chemical composition of CsPbBr3 perovskite film. The Raman spectra of the CuPc film on glass substrate were performed by a Raman spectrometer (LabRAM HR800, Horiba JobinYvon) with a 532 nm laser source. All the XPS spectra were obtained in the constant pass energy mode, where the pass energy of the analyzer was set at 20 eV. Here the binding energy of the C 1s peak (285 eV) arising from adventitious carbon was used for the energy calibration. UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UV 2600, Shimadzu) was utilized to obtain the absorption spectra of CsPbBr3 and CsPbBr3/CuPc films. The steady-state photoluminescence measurements were taken using a spectrometer (LabRAM HR800, Horiba JobinYvon) under an excitation laser with a wavelength of 325 nm. The time-resolved photoluminescence decay transients were measured at 525 nm using excitation with a 478-nm light pulse from a HORIBA Scientific DeltaPro fluorimeter. Current density–voltage (J–V) curves were recorded under AM 1.5, 100 mW cm−2 simulated sunlight (Oriel 94043A, Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA, USA) with an electrochemical station (Autolab PGSTAT302 N, Metrohm Autolab, Utrecht, The Netherlands), previously calibrated with an NREL-calibrated Si solar cell. The measurements were taken with a black metal mask with a circular aperture (0.071 cm2) smaller than the active area of the square solar cell (1.5 × 1.5 cm2). The incident photon to current conversion efficiency (IPCE) was performed employing a xenon lamp coupled with a monochromator (TLS1509, Zolix) controlled by a computer.

4 Results and Discussion

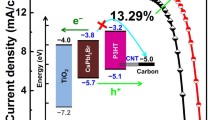

Figure 1a shows the schematic cross-sectional view of the CuPc-based CsPbBr3 PSC. The cell consists of functional layers of FTO/compact TiO2/mesoporous TiO2/inorganic perovskite CsPbBr3/CuPc/carbon. Figure 1b displays the schematic energy-level alignment of the PSCs device. The TiO2 compact layer is used as the electron-collecting layer, and the mesoporous TiO2 layer is used as the scaffold for light-sensitive absorption material. According to previous study, the EC, EF, and EV of TiO2 are 4.0, 4.15, and 7.6 eV, respectively [52]. The counter electrode is printed by a low-temperature printable carbon paste. Compared to the traditional organometal CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite material, CsPbBr3 owns a wider band gap of 2.3 eV, a work function of 3.95 eV, and a valence band energy of 5.75 eV [53]. CuPc is a typical organic small molecular photoelectric semiconductor material with the corresponding molecular structure as shown in Fig. S1. The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) levels of CuPc are ascribed to − 5.2 and − 3.5 eV, respectively [54]. What is more, the gap between EF and EV is reported to be 0.7 eV [55]. It can be found that the device exhibits a smooth energy-level transition by using CuPc as the HTM. The proposed band bending at interfaces is illustrated in Fig. 1c. Under illumination, free charge carriers generated in the CsPbBr3 layer can be extracted by transferring electrons (filled circle) and holes (open circle) to TiO2 and CuPc, since the energy-level alignments are appropriate. Besides, the conduction band offset between the CsPbBr3 layer and CuPc layer (0.5 eV) provides an energy barrier that prevents photogenerated electrons from flowing to the CuPc layer, whereas the valence band offset provides an additional driving force for the flow of photogenerated holes to the CuPc layer. The insertion of the CuPc layer not only prevents electron flow from CsPbBr3 to the anode but may also reduce surface recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes at the CsPbBr3/carbon interface [46, 56]. The final collection of the holes is extracted by carbon through the CuPc/carbon interface from the HOMO of CuPc (− 5.2 eV) to carbon (− 5.0 eV), while electrons are collected by FTO (− 4.6 eV) [47, 48].

a Schematic cross-sectional view of the CuPc-based CsPbBr3 PSC with a printable low-temperature carbon electrode. b Schematic energy-level alignment at interfaces. EVAC is the vacuum energy, EC is the conduction band edges, EF is the Fermi levels, and EV is the valence band edges. c Schematic illustration of proposed band bending at interfaces

The film quality of the CsPbBr3 and the surface morphology of the CsPbBr3 film with CuPc on the top, as well as the cross-sectional view of the whole device, are measured by high-resolution SEM, as depicted in Fig. 2a–d. The as-formed CsPbBr3 film possesses the characteristic of well surface coverage on the substrate. Relatively uniform grain size ranging from 100 to 1000 nm can be derived from Fig. 2a. However, striking different top-view morphology is revealed by depositing CuPc on the surface of the perovskite grains (Fig. 2b). The higher-magnification image derived from Fig. S2 demonstrates a nanorod-like morphology of the CuPc aggregated by layered deposition. Decorated with the CuPc film, the perovskite grains become sea cucumber-like. The molecular interactions in the CuPc nanorods are enhanced due to the strong π–π stacking between the layered CuPc molecular, which favors the formation of high carrier mobility to some extent. [57] Moreover, depositing thin CuPc can also compensate some defects on the surface of the CsPbBr3 as well as induce a large interfacial area of the CuPc, which is conductive to a good contact with the counter electrode, correspondingly favoring the hole transported from the CuPc to the carbon. The cross-sectional SEM images of the whole device shown in Fig. 2c, d demonstrate a well-defined layer-by-layer structure with sharp interfaces. The thickness of the mp-TiO2, perovskite capping layer, and carbon layers is determined as 600 nm, 500 nm, and 50 μm, respectively. The CuPc layer is too thin to be identified in this scale. The line-scan analysis of EDX map is further conducted to investigate the distribution of components in the solar cell, as shown in Fig. S3. The evident peak from Cu proves the existence of CuPc between the interface of CsPbBr3 and carbon. According to the result of four-point probe resistivity measurement, the carbon electrode shows a sheet resistance of around 70 Ω sq−1 and exhibits a good electrical conductivity. Figure 2e shows the XRD patterns of the FTO/TiO2 (black curve), FTO/TiO2/CsPbBr3 (red curve), and FTO/TiO2/CsPbBr3/CuPc (blue curve) films. Obvious diffraction peaks at 15.1°, 21.4°, 30.6°, 34.3°, and 43.7° are consistent with the planes of (100), (110), (200), (210), and (220) of CsPbBr3, respectively [35]. Impure peaks at 11.6° and 29.3° (marked by rhombuses) may attribute to (002) and (220) planes of by-product CsPb2Br5, which is hard to eliminate when to obtain CsPbBr3. The occurrence of CsPb2Br5 in the final product can be attributed to the metastable state in the cubic phase, non-stoichiometric material transfer, or structural rearrangement [58, 59]. The generation of secondary-phase CsPb2Br5 in the product can be ascribed to the following process:

SEM images of a top view of the CsPbBr3 perovskite film and b top view of the CsPbBr3 perovskite film deposited with CuPc. c Cross-sectional SEM image of the whole device. d Close-up of the structure under higher magnification. e XRD spectra of the FTO/TiO2, FTO/TiO2/CsPbBr3, and FTO/TiO2/CsPbBr3/CuPc. f UV–Vis absorbance spectra of the CuPc, FTO/TiO2/CsPbBr3, and FTO/TiO2/CsPbBr3/CuPc

The excess PbBr2 or the poor solubility of CsBr in methyl alcohol could facilitate the transformation at a low temperature [60]. CsPb2Br5 crystal is reported to exhibit an inactive photoluminescence behavior and a large indirect band gap of approximately 3.1 eV [61], which are unfavorable in the application of photovoltaic device and need to be eliminated by future process optimization. After coated by CuPc, the XRD patterns of the film show negligible changes, mainly due to the amorphous state of the CuPc [42]. In the Raman spectra (Fig. S4), the peak at 680.2 cm−1 is ascribed to the breathing vibration band of phthalocyanine ring, the peak at 1140.5 cm−1 is ascribed to the breathing vibration band of benzene ring, and the peaks at 1137.5, 1452.0, and 1526.5 cm−1 are attributed to the stretching vibration band of C–C, C–N, and C=C bond, respectively [62]. UV–Vis absorbance spectra of the CuPc, FTO/TiO2/CsPbBr3, and FTO/TiO2/CsPbBr3/CuPc are also demonstrated in Fig. 2f. The CsPbBr3 film strongly absorbs light with the wavelength between 300 and 540 nm, owning to the relatively wide band gap (2.3 eV) as shown in Fig. S5. Pristine CuPc demonstrates a wide spectral ranging from 500 to 800 nm, and peaks at 625 and 696 nm, which are ascribed to the Q-band of CuPc. The peak at 625 nm is the absorbance peak of the CuPc dimer, and the peak at 696 nm comes from the CuPc monomer [63, 64]. In the presence of CuPc, an enhancement in absorption is observed, especially in the region of 537–800 nm. Correspondingly, the color of the films changes from golden yellow to light green, as shown in the inset of Fig. 2f.

Steady-state PL and time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) are judiciously employed for the CsPbBr3 film and the CsPbBr3 film coated by CuPc, which are deposited on the quartz glasses. As shown in Fig. 3a, both samples under the same laser pulse energy exhibit PL emission peaks at 525 nm arising from the CsPbBr3 perovskite layer. Significant quenching effect is observed when the perovskite layer interfaces with the CuPc layer, indicating that CuPc is effective in hole extraction. This owes to the high mobility and high interfacial film quality together with intimate contact with the CsPbBr3 film formed by excellent π–π stacking. In order to evaluate the hole-extraction rate and bimolecular recombination process of the free electrons and holes, TRPL decay is further performed via monitoring the peak emission at 525 nm. The results are shown in Fig. 3b. The excitation impinges on the sample from the glass side with a pulsed laser at 478 nm. By biexponential fitting of the dynamic TRPL curve, the pure CsPbBr3 perovskite film exhibits a carrier lifetime of 2.82 ns, whereas the addition of nanorod-like CuPc accelerates the PL decay with an observed carrier lifetime of 0.79 ns. Here the carrier lifetime in the perovskite film describes various radiative and non-radiative loss channels responsible for photoexcited carrier recombination [65]. The smaller lifetime induced by the CuPc nanorods quenching indicates a fast hole-diffusion process, a reduced trap-assisted recombination, and an efficient hole-extraction capability [40].

The photovoltaic performances of the devices with 60-nm CuPc as HTM or without any HTM were characterized by J–V measurements under simulated AM 1.5G solar irradiation at 100 mW cm−2 in the air (Fig. 4a). The results are summarized in Table 1. The optimized device with CuPc as HTM shows a short-circuit current density (JSC) of 6.62 mA cm−2, an open-circuit voltage (VOC) of 1.26 V, a fill factor (FF) of 0.74, and a champion PCE of 6.21%, showing 63% enhancement than the HTM-free device (3.8%). The corresponding IPCE spectra are displayed in Fig. 4b. The IPCE starts to increase at 540 nm, consistent with the UV–Vis spectrum of CsPbBr3. After applying CuPc as the HTM, the IPCE shows noticeable improvement in the region between 300 and 540 nm due to more effective charge collection and extraction. Note that the IPCE curve also exhibits a blue-shift character, leading to an effective use for the near-ultraviolet light. Integrating the overlap of the IPCE spectra of the CuPc-based and HTM-free devices yields the current density of 6.58 and 4.48 mA cm−2, respectively, in good agreement with the experimentally obtained JSC. Figure 4c–f is box charts exhibiting the statistical features (JSC, VOC, FF, and PCE) of the carbon-based CsPbBr3 PSCs with CuPc as HTM and those without HTM. It is obvious that the PCE is enhanced after introducing CuPc, mainly ascribing to the improved JSC. Moreover, the thickness of the CuPc layer also plays a vital role in affecting the performance of the solar cells (see Fig. S7 and Table S2). If the CuPc layer is too thin, the hole transportation function of the CuPc will not work effectively; if the CuPc is too thick, the series resistance of the device will increase due to relatively low conductivity of the pristine CuPc, resulting in a poor performance. Thus, the optimized thickness of the CuPc layer is very important, and 60 nm is obtained in this study. Generally, PSCs suffer from hysteresis phenomena: VOC and FF varied under different scan directions. As displayed in Fig. S8, despite the improvement in efficiency after introducing CuPc as HTM, our device still suffer from severe hysteresis effect: Efficiency at forward scan (3.12%) is only 54% of the efficiency at reverse scan (5.74%). Recent studies suggest that J–V hysteresis is related to the presence of defects and trap states at the perovskite/electron transport layer and/or perovskite/hole transport layer interfaces [66,67,68,69]. The combination of ion migration in the perovskite film and interfacial recombination is thought to be responsible for many of the observed hysteresis behaviors [70,71,72]. These phenomena may be further eliminated via interfacial modification or interface passivation [73,74,75,76,77].

a Best performed current density–voltage (J–V) curves of typical small-area (0.071 cm2) carbon-based CsPbBr3 PSCs with CuPc as HTM or without HTM measured under 100 mW cm−2 photon flux (AM 1.5G), respectively. b IPCE spectra and corresponding integrated photocurrents. Box charts exhibiting the statistical features of c JSC, d VOC, e FF, and f PCE of the carbon-based CsPbBr3 PSCs with CuPc as HTM or without HTM

To further evaluate the recombination in the HTM-free and CuPc-based CsPbBr3 PSCs, EIS was applied to track the interface charge behavior. Measurements were taken at a bias of 1.0 V in the frequency ranging from 107 to 10 Hz under dark condition. Figure 5a, b shows the Nyquist plots of two devices (with CuPc or HTM-free), and an equivalent circuit (inset in Fig. 5a) is used to fit the curves. As can be found, there are two well-defined semicircles, including a small one in the high frequency range (magnified in Fig. 5b) and a large one in the low frequency range. The right semicircle in the low frequency range is mainly attributed to the recombination resistance (Rrec) at the TiO2/perovskite interface. The small semicircle corresponding to the high-frequency part stands for the charge transfer resistance (Rct) at the perovskite/HTM or perovskite/carbon interface [78,79,80]. Compared with the HTM-free CsPbBr3 PSC, the Rrec increases from 2.87 to 3.41 kΩ after using CuPc as HTM in the device. The larger Rrec of the device with CuPc at the same forward bias voltage suggests that CuPc as the HTM is superior in preventing charge recombination. Furthermore, introducing CuPc will also lower the Rct (from 213.0 to 45.6 Ω), indicating a more efficient charge transfer process than that occurred in the HTM-free device. All these results lead to an enhanced JSC and thereby an improved PCE. A further explanation is that the appropriate energy level and high hole mobility of the CuPc may help to accelerate the extractions of photon-generated carriers, resulting in a larger Rrec and a smaller Rct. The favorable effect of the CuPc HTM layer on the device operation is summarized by the device models shown in Fig. 5c, similar to the planar heterojunction organic photovoltaic devices [81]. A perforation in the perovskite film (circled by dash line in red) is sketched for better illustration of the working mechanism of our devices. It does not indicate that the perovskite film is totally discontinuous since the hole is enlarged for clarity. In perovskites, bimolecular recombination is caused by the recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes, whereas monomolecular recombination is from photoexcited carriers and unintentionally trap states [82]. It is proposed that large perovskite grains with few trap states show bimolecular recombination and high device efficiency, whereas the perovskite films with trap states present monomolecular recombination and low device efficiency [3]. The carriers trapped by the trap states will lead to slow response of the photocurrent through the delay in charge transport by trapping and detrapping processes and cause losses in carrier collection which will lead to a low JSC. Hence, there are mainly two reasons for the enhanced photovoltaic performance of the CuPc-based PSCs. First, pin-holes in the perovskite layer (as shown in Fig. S9), which are hard to eliminate by technological means, will lead to the formation of defects, acting as centers to facilitate the recombination of holes and electrons. Introducing CuPc as HTM layer can build a Schottky barrier at the perovskite/carbon interfaces and suppress carrier recombination [83, 84]. Second, the CuPc HTM layer provides a smoother energy-level transition, reducing trap states and monomolecular recombination, which will benefit for high efficient solar cells [3, 85].

Moreover, CuPc-based CsPbBr3 PSCs with large active area (2.25 cm2) were also fabricated. Figure 6a shows the J–V plots of a large-area PSC under AM1.5 G standard solar light. The device shows a Voc of 1.285 V, a Jsc of 5.695 mA cm−2, a FF of 0.645, reaching a PCE of 4.72%. Measuring the steady-state power output directly at a given bias is also feasible to estimate the PCE. As shown in Fig. 6b, we recorded the photocurrent density of the device held at a forward bias of 0.85 V near its maximum output power as a function of time, so as to monitor the stabilized power output under working conditions. The photocurrent density stabilizes within seconds to approximately 3.17 mA cm−2, yielding the stabilized power conversion efficiency around 2.65% measured after 300 s. Here, the decay of Jsc toward the steady current is ascribed to the capture of build-up holes in surface states associated with recombination [86], similar to that occurred in traditional organic–inorganic hybrid PSCs [34, 87].

a J–V plot of the carbon-based perovskite solar cell with a large active area of 2.25 cm2. b Stabilized power output measurement for the large-area PSC. c Normalized PCE of CsPbBr3/CuPc/carbon-, CsPbBr3/carbon-, and CH3NH3PbI3/carbon-based PSCs versus storage time in ambient air (30–40% RH, 25 °C) without encapsulation. d Normalized PCE of CsPbBr3/CuPc/carbon-, CsPbBr3/carbon-, and CH3NH3PbI3/carbon-based PSCs versus storage time heated at high temperature (100 °C) in a high-humidity ambient environment (70–80% RH, 100 °C) without encapsulation

Long-term stability is a critical concern for practical applications of PSCs. Figure 6c presents the room-temperature stability test of the CuPc-based CsPbBr3 PSCs in comparison with the HTM-free CsPbBr3 devices and the classical CH3NH3PbI3/carbon devices. The devices without encapsulation were stored in dark with a humidity of 30–40% RH. Both the CuPc-based CsPbBr3 PSCs and HTM-free CsPbBr3 PSCs exhibit excellent stability beyond 2000 h, while the organic ones start degrading at 800 h. Thermal stability of the devices was further evaluated in a harsh environment (the humidity of 70–80% RH and the temperature of 100 °C), as shown in Fig. 6d. Obviously, the performance of CH3NH3PbI3/carbon devices decays rapidly, since the high humidity and high storing temperature accelerate the degradation of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite light absorber. The HTM-free CsPbBr3 devices also show a PCE loss of 37% after 944 h, similar to the previous research [35]. However, the CuPc-based CsPbBr3 devices show an outstanding thermal stability (without evident decay) during the whole testing period. The organic CH3NH3+ cation is more vulnerable to moisture and has higher volatility than the inorganic Cs+ cation, leading to rapid degradation of the CH3NH3PbI3 devices under relatively high RH and temperature environment [35]. The introduction of the CuPc film and carbon film, which can act as shields to prevent the deliquescing of the underlying perovskite layer, obtains the best hydrophobicity and thus results in the best stability of CuPc-based CsPbBr3 PSCs.

5 Conclusion

In summary, cost-effective p-type material CuPc was introduced as HTM layer in the carbon-based CsPbBr3 inorganic PSCs. The deposited CuPc layer exhibits a nanorods morphology and an intimate contact with the perovskite layer, preventing direct contact between the perovskite layer and carbon electrode. The CuPc layer can effectively extract the photon-generated carriers and accelerate the hole-diffusion process, obtaining a decent PCE (6.21%) with high reproducibility. Compared with HTM-free CsPbBr3/carbon devices, the enhanced PCE may be ascribed to a more efficient charge transfer and a more suppressed charge recombination. Moreover, the newly developed devices demonstrate a dramatically enhanced durability under ambient atmosphere and a promising thermal stability in relatively harsh condition. The enhanced PCE and excellent stability of our devices offer a new device designing strategy and promise a reality of commercial application for PSCs with cost-effective, mass manufacturing solar technology that is compatible with current large-scale printing infrastructure.

References

M.M. Lee, J. Teuscher, T. Miyasaka, T.N. Murakami, H.J. Snaith, Efficient hybrid solar cells based on meso-superstructured organometal halide perovskites. Science 338(6107), 643–647 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1228604

J.-H. Im, C.-R. Lee, J.-W. Lee, S.-W. Park, N.-G. Park, 6.5% efficient perovskite quantum-dot-sensitized solar cell. Nanoscale 3(10), 4088–4093 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1039/c1nr10867k

W. Nie, H. Tsai, R. Asadpour, J.-C. Blancon, A.J. Neukirch et al., High-efficiency solution-processed perovskite solar cells with millimeter-scale grains. Science 347(6221), 522–525 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa0472

W. Chen, Y. Wu, Y. Yue, J. Liu, W. Zhang et al., Efficient and stable large-area perovskite solar cells with inorganic charge extraction layers. Science 350(6263), 944–948 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad1015

J. Burschka, N. Pellet, S.-J. Moon, R. Humphry-Baker, P. Gao, M.K. Nazeeruddin, M. Grätzel, Sequential deposition as a route to high-performance perovskite-sensitized solar cells. Nature 499(7458), 316–319 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12340

M. Liu, M.B. Johnston, H.J. Snaith, Efficient planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells by vapour deposition. Nature 501(7467), 395–398 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12509

J.H. Noh, S.H. Im, J.H. Heo, T.N. Mandal, S.I. Seok, Chemical management for colorful, efficient, and stable inorganic–organic hybrid nanostructured solar cells. Nano Lett. 13(4), 1764–1769 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1021/nl400349b

W. Zhu, C. Bao, F. Li, X. Zhou, J. Yang, T. Yu, Z. Zou, An efficient planar-heterojunction solar cell based on wide-bandgap CH3NH3PbI2.1Br 0.9 perovskite film for tandem cell application. Chem. Commun. 52(2), 304–307 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5CC07673K

M. Hu, C. Bi, Y. Yuan, Y. Bai, J. Huang, Stabilized wide bandgap MAPbBrxI3–x perovskite by enhanced grain size and improved crystallinity. Adv. Sci. 3(6), 1500301 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.201500301

J.H. Heo, S.H. Im, J.H. Noh, T.N. Mandal, C.-S. Lim et al., Efficient inorganic–organic hybrid heterojunction solar cells containing perovskite compound and polymeric hole conductors. Nat. Photonics 7(6), 486–491 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2013.80

W.A. Laban, L. Etgar, Depleted hole conductor-free lead halide iodide heterojunction solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 6(11), 3249–3253 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1039/C3EE42282H

S. Aharon, S. Gamliel, B.E. Cohen, L. Etgar, Depletion region effect of highly efficient hole conductor free CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite solar cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16(22), 10512–10518 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CP00460D

S. Aharon, B.E. Cohen, L. Etgar, Hybrid lead halide iodide and lead halide bromide in efficient hole conductor free perovskite solar cell. J. Phys. Chem. C 118(30), 17160–17165 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1021/jp5023407

S.D. Stranks, G.E. Eperon, G. Grancini, C. Menelaou, M.J. Alcocer, T. Leijtens, L.M. Herz, A. Petrozza, H.J. Snaith, Electron-hole diffusion lengths exceeding 1 micrometer in an organometal trihalide perovskite absorber. Science 342(6156), 341–344 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1243982

Q. Dong, Y. Fang, Y. Shao, P. Mulligan, J. Qiu, L. Cao, J. Huang, Electron-hole diffusion lengths > 175 μm in solution-grown CH3NH3PbI3 single crystals. Science 347(6225), 967–970 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa5760

A. Kojima, K. Teshima, Y. Shirai, T. Miyasaka, Organometal halide perovskites as visible-light sensitizers for photovoltaic cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131(17), 6050–6051 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1021/ja809598r

M. Saliba, T. Matsui, K. Domanski, J.-Y. Seo, A. Ummadisingu et al., Incorporation of rubidium cations into perovskite solar cells improves photovoltaic performance. Science 354(6309), 206–209 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah5557

D. Bi, C. Yi, J. Luo, J.-D. Décoppet, F. Zhang, S.M. Zakeeruddin, X. Li, A. Hagfeldt, M. Grätzel, Polymer-templated nucleation and crystal growth of perovskite films for solar cells with efficiency greater than 21%. Nat. Energy 1, 16142 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2016.142

Best research-cell efficiencies NREL (2016). http://www.nrel.gov/ncpv/images/efficiency_chart.jpg

M.A. Green, K. Emery, Y. Hishikawa, W. Warta, E.D. Dunlop, Solar cell efficiency tables. Prog. Photovoltaics 23(1), 1–9 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1002/pip.2573

J. Liu, Y. Wu, C. Qin, X. Yang, T. Yasuda et al., A dopant-free hole-transporting material for efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 7(9), 2963–2967 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1039/C4EE01589D

S. Kazim, F.J. Ramos, P. Gao, M.K. Nazeeruddin, M. Grätzel, S. Ahmad, A dopant free linear acene derivative as a hole transport material for perovskite pigmented solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 8(6), 1816–1823 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5EE00599J

W.H. Nguyen, C.D. Bailie, E.L. Unger, M.D. McGehee, Enhancing the hole-conductivity of spiro-OMeTAD without oxygen or lithium salts by using spiro(TFSI)2 in perovskite and dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136(31), 10996–11001 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1021/ja504539w

Z. Hawash, L.K. Ono, S.R. Raga, M.V. Lee, Y. Qi, Air-exposure induced dopant redistribution and energy level shifts in spin-coated spiro-MeOTAD films. Chem. Mater. 27(2), 562–569 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/cm504022q

X. Li, D. Bi, C. Yi, J.-D. Décoppet, J. Luo, S.M. Zakeeruddin, A. Hagfeldt, M. Grätzel, A vacuum flash–assisted solution process for high-efficiency large-area perovskite solar cells. Science 353(6294), 58–62 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf8060

S.N. Habisreutinger, T. Leijtens, G.E. Eperon, S.D. Stranks, R.J. Nicholas, H.J. Snaith, Carbon nanotube/polymer composites as a highly stable hole collection layer in perovskite solar cells. Nano Lett. 14(10), 5561–5568 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1021/nl501982b

J.H. Heo, S.H. Im, CH3NH3PbBr3–CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite–perovskite tandem solar cells with exceeding 2.2 V open circuit voltage. Adv. Mater. 28(25), 5121–5125 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201501629

A. Dualeh, T. Moehl, M.K. Nazeeruddin, M. Grätzel, Temperature dependence of transport properties of Spiro-MeOTAD as a hole transport material in solid-state dye-sensitized solar cells. ACS Nano 7(3), 2292–2301 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1021/nn4005473

J. Burschka, A. Dualeh, F. Kessler, E. Baranoff, N.-L. Cevey-Ha, C. Yi, M.K. Nazeeruddin, M. Grätzel, Tris (2-(1 H-pyrazol-1-yl) pyridine) cobalt (III) as p-type dopant for organic semiconductors and its application in highly efficient solid-state dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133(45), 18042–18045 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1021/ja207367t

T. Leijtens, J. Lim, J. Teuscher, T. Park, H.J. Snaith, Charge density dependent mobility of organic hole-transporters and mesoporous TiO2 determined by transient mobility spectroscopy: implications to dye-sensitized and organic solar cells. Adv. Mater. 25(23), 3227–3233 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201300947

H. Tan, A. Jain, O. Voznyy, X. Lan, F.P.G. De Arquer et al., Efficient and stable solution-processed planar perovskite solar cells via contact passivation. Science 355(6326), 722–726 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aai9081

P. Luo, W. Xia, S. Zhou, L. Sun, J. Cheng, C. Xu, Y. Lu, Solvent engineering for ambient-air-processed, phase-stable CsPbI3 in perovskite solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7(18), 3603–3608 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b01576

M. Kulbak, D. Cahen, G. Hodes, How important is the organic part of lead halide perovskite photovoltaic cells? Efficient CsPbBr3 cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6(13), 2452–2456 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00968

R.J. Sutton, G.E. Eperon, L. Miranda, E.S. Parrott, B.A. Kamino et al., Bandgap-tunable cesium lead halide perovskites with high thermal stability for efficient solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 6(8), 1502458 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201502458

X. Chang, W. Li, L. Zhu, H. Liu, H. Geng, S. Xiang, J. Liu, H. Chen, Carbon-based CsPbBr3 perovskite solar cells: all-ambient processes and high thermal stability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 8(49), 33649–33655 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b11393

J. Liang, C. Wang, Y. Wang, Z. Xu, Z. Lu et al., All-inorganic perovskite solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138(49), 15829–15832 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.6b10227

P. Qin, S. Tanaka, S. Ito, N. Tetreault, K. Manabe, H. Nishino, M.K. Nazeeruddin, M. Grätzel, Inorganic hole conductor-based lead halide perovskite solar cells with 12.4% conversion efficiency. Nat. Commun. 5, 3834 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4834

A.W. Hains, Z. Liang, M.A. Woodhouse, B.A. Gregg, Molecular semiconductors in organic photovoltaic cells. Chem. Rev. 110(11), 6689–6735 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1021/cr9002984

T. Stübinger, W. Brütting, Exciton diffusion and optical interference in organic donor–acceptor photovoltaic cells. J. Appl. Phys. 90(7), 3632–3641 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1394920

X. Zhang, M. Yang, W. Cheng, L. Wang, Sun, Boosting the efficiency and the stability of low cost perovskite solar cells by using CuPc nanorods as hole transport material and carbon as counter electrode. Nano Energy 20, 108–116 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2015.11.034

W. Ke, D. Zhao, C.R. Grice, A.J. Cimaroli, G. Fang, Y. Yan, Efficient fully-vacuum-processed perovskite solar cells using copper phthalocyanine as hole selective layers. J. Mater. Chem. A 3(47), 23888–23894 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5TA07829F

C.V. Kumar, G. Sfyri, D. Raptis, E. Stathatos, P. Lianos, Perovskite solar cell with low cost Cu-phthalocyanine as hole transporting material. RSC Adv. 5(5), 3786–3791 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C4RA14321C

E. Nouri, Y. Wang, Q. Chen, J. Xu, G. Paterakis et al., Introduction of graphene oxide as buffer layer in perovskite solar cells and the promotion of soluble n-butyl-substituted copper phthalocyanine as efficient hole transporting material. Electrochim. Acta 233, 36–43 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2017.03.027

C. Chen, Z. Hong, G. Li, Q. Chen, H. Zhou, Y. Yang, One-step, low-temperature deposited perovskite solar cell utilizing small molecule additive. J. Photon. Energy 5(1), 057405 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JPE.5.057405

Z. Ku, X. Xia, H. Shen, N.H. Tiep, H.J. Fan, A mesoporous nickel counter electrode for printable and reusable perovskite solar cells. Nanoscale 7(32), 13363–13368 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5NR03610K

Z. Liu, M. Zhang, X. Xu, L. Bu, W. Zhang et al., p-Type mesoscopic NiO as an active interfacial layer for carbon counter electrode based perovskite solar cells. Dalton Trans. 44(9), 3967–3973 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C4DT02904F

Z. Ku, Y. Rong, M. Xu, T. Liu, H. Han, Full printable processed mesoscopic CH3NH3PbI3/TiO2 heterojunction solar cells with carbon counter electrode. Sci. Rep. 3, 3132 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03132

A. Mei, X. Li, L. Liu, Z. Ku, T. Liu et al., A hole-conductor–free, fully printable mesoscopic perovskite solar cell with high stability. Science 345(6194), 295–298 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254763

H. Chen, S. Yang, Carbon-based perovskite solar cells without hole transport materials: the front runner to the market? Adv. Mater. 29(24), 1603994 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201603994

A. Kay, M. Grätzel, Low cost photovoltaic modules based on dye sensitized nanocrystalline titanium dioxide and carbon powder. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 44(1), 99–117 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0927-0248(96)00063-3

Z. Liu, T. Shi, Z. Tang, B. Sun, G. Liao, Using a low-temperature carbon electrode for preparing hole-conductor-free perovskite heterojunction solar cells under high relative humidity. Nanoscale 8(13), 7017–7023 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5NR07091K

H. Zhou, Q. Chen, G. Li, S. Luo, T. Song et al., Interface engineering of highly efficient perovskite solar cells. Science 345(6196), 542–546 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254050

M. Kulbak, S. Gupta, N. Kedem, L. Levine, T. Bendikov, G. Hodes, D. Cahen, Cesium enhances long-term stability of lead bromide perovskite-based solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7(1), 167–172 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b02597

S. Uchida, J. Xue, B.P. Rand, S.R. Forrest, Organic small molecule solar cells with a homogeneously mixed copper phthalocyanine: C60 active layer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84(21), 4218–4220 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1755833

L. Yan, N.J. Watkins, S. Zorba, Y. Gao, C.W. Tang, Direct observation of Fermi-level pinning in Cs-doped CuPc film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 79(25), 4148–4150 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1426260

C.M. Chuang, P.R. Brown, V. Bulovic, M.G. Bawendi, Improved performance and stability in quantum dot solar cells through band alignment engineering. Nat. Mater. 13(8), 796–801 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3984

J. Yang, D. Yan, Weak epitaxy growth of organic semiconductor thin films. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38(9), 2634–2645 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1039/B815723P

C.C. Stoumpos, C.D. Malliakas, M.G. Kanatzidis, Semiconducting Tin and Lead Iodide perovskites with organic cations: phase transitions, high mobilities, and near-infrared photoluminescent properties. Inorg. Chem. 52(15), 9019–9038 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1021/ic401215x

D.M. Trots, S.V. Myagkota, High-temperature structural evolution of caesium and rubidium triiodoplumbates. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 69(10), 2520–2526 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2008.05.007

X. Zhang, B. Xu, J. Zhang, Y. Gao, Y. Zheng, K. Wang, X. Sun, All-Inorganic perovskite nanocrystals for high-efficiency light emitting diodes: dual-phase CsPbBr3–CsPb2Br5 composites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26(25), 4595–4600 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201600958

B. Alamer, A. Shkurenko, J. Yin, A.M. El-Zohry, I. Gereige, A. AlSaggaf, O.F. Mohammed, M. Eddaoudi, O.M. Bakr, CsPb2Br5 single crystals: synthesis and characterization. Chemsuschem 10(19), 3746–3749 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.201701131

K. Ishii, S. Mitsumura, Y. Hibino, R. Hagiwara, H. Nakayama, Preparation of phthalocyanine and octacyanophthalocyanine films by CVD on metal surfaces, and in SITU observation of the molecular processes by Raman spectroscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 33, 1324–1331 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-4332(88)90451-5

H. Laurs, G. Heiland, Electrical and optical properties of phthalocyanine films. Thin Solid Films 149(2), 129–142 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-6090(87)90288-4

M. El-Nahass, Z. El-Gohary, H. Soliman, Structural and optical studies of thermally evaporated CoPc thin films. Opt. Laser Technol. 35(7), 523–531 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0030-3992(03)00068-9

Q. Chen, H. Zhou, Y. Fang, A.Z. Stieg, T.-B. Song et al., The optoelectronic role of chlorine in CH3NH3PbI3 (Cl)-based perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 6, 7269 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8269

Y. Shao, Z. Xiao, C. Bi, Y. Yuan, J. Huang, Origin and elimination of photocurrent hysteresis by fullerene passivation in CH3NH3PbI3 planar heterojunction solar cells. Nat. Commun. 5, 5784 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6784

F. Giordano, A. Abate, J.P.C. Baena, M. Saliba, T. Matsui et al., Enhanced electronic properties in mesoporous TiO2 via lithium doping for high-efficiency perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 7, 10379 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10379

C. Tao, S. Neutzner, L. Colella, S. Marras, A.R.S. Kandada et al., 17.6% stabilized efficiency in low-temperature processed planar perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 8(8), 2365–2370 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5EE01720C

J.P.C. Baena, W. Tress, K. Domanski, E.H. Anaraki, S.H.T. Cruz et al., Identifying and suppressing interfacial recombination to achieve high open-circuit voltage in perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 10(5), 1207–1212 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/C7EE00421D

D.A. Jacobs, Y. Wu, H. Shen, C. Barugkin, F.J. Beck, T.P. White, K. Weber, K.R. Catchpole, Hysteresis phenomena in perovskite solar cells: the many and varied effects of ionic accumulation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19(4), 3094–3103 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/C6CP06989D

B. Chen, M. Yang, S. Priya, K. Zhu, Origin of J–V hysteresis in perovskite solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7(5), 905–917 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b00215

G. Richardson, S.E.J. O’Kane, R.G. Niemann, T.A. Peltola, J.M. Foster, P.J. Cameron, A.B. Walker, Can slow-moving ions explain hysteresis in the current–voltage curves of perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 9(4), 1476–1485 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5EE02740C

Y. Dong, W. Li, X. Zhang, Q. Xu, Q. Liu, C. Li, Z. Bo, Highly efficient planar perovskite solar cells via interfacial modification with fullerene derivatives. Small 12(8), 1098–1104 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201503361

H. Li, Y. Xue, B. Zheng, J. Tian, H. Wang, C. Gao, X. Liu, Interface modification with PCBM intermediate layers for planar formamidinium perovskite solar cells. RSC Adv. 7(48), 30422–30427 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/C7RA04311B

J. Peng, Y. Wu, W. Ye, D.A. Jacobs, H. Shen et al., Interface passivation using ultrathin polymer–fullerene films for high efficiency perovskite solar cells with negligible hysteresis. Energy Environ. Sci. 10(8), 1792–1800 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/C7EE01096F

Y. Hou, W. Chen, D. Baran, T. Stubhan, N.A. Luechinger et al., Overcoming the interface losses in planar heterojunction perovskite-based solar cells. Adv. Mater. 28(25), 5112–5120 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201504168

Y. Yang, M. Yang, D.T. Moore, Y. Yan, E.M. Miller, K. Zhu, M.C. Beard, Top and bottom surfaces limit carrier lifetime in lead iodide perovskite films. Nat. Energy 2, 16207 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2016.207

X. Huang, Z. Hu, J. Xu, P. Wang, L. Wang, J. Zhang, Y. Zhu, Low-temperature processed SnO2 compact layer by incorporating TiO2 layer toward efficient planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 164, 87–92 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2017.02.010

D. Yang, R. Yang, J. Zhang, Z. Yang, S.F. Liu, C. Li, High efficiency flexible perovskite solar cells using superior low temperature TiO2. Energy Environ. Sci. 8(11), 3208–3214 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5EE02155C

K. Wang, Y. Shi, Q. Dong, Y. Li, S. Wang, X. Yu, M. Wu, T. Ma, Low-temperature and solution-processed amorphous WOX as electron-selective layer for perovskite solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6(5), 755–759 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00010

V.I. Adamovich, S.R. Cordero, P.I. Djurovich, A. Tamayo, M.E. Thompson, B.W. D’Andrade, S.R. Forrest, New charge-carrier blocking materials for high efficiency OLEDs. Org. Electron. 4(2), 77–87 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgel.2003.08.003

Y. Yamada, T. Nakamura, M. Endo, A. Wakamiya, Y. Kanemitsu, Photocarrier recombination dynamics in perovskite CH3NH3PbI3 for solar cell applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136(33), 11610–11613 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1021/ja506624n

Q. Wang, Y. Shao, Q. Dong, Z. Xiao, Y. Yuan, J. Huang, Large fill-factor bilayer iodine perovskite solar cells fabricated by a low-temperature solution-process. Energy Environ. Sci. 7(7), 2359–2365 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1039/C4EE00233D

Y. Fang, C. Bi, D. Wang, J. Huang, The functions of fullerenes in hybrid perovskite solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 2(4), 782–794 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.6b00657

D. Song, P. Cui, T. Wang, D. Wei, M. Li et al., Managing carrier lifetime and doping property of lead halide perovskite by postannealing processes for highly efficient perovskite solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 119(40), 22812–22819 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b06859

C.Y. Cummings, F. Marken, L.M. Peter, A.A. Tahir, K.U. Wijayantha, Kinetics and mechanism of light-driven oxygen evolution at thin film α-Fe2O3 electrodes. Chem. Commun. 48(14), 2027–2029 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1039/C2CC16382A

W. Nie, J.-C. Blancon, A.J. Neukirch, K. Appavoo, H. Tsai et al., Light-activated photocurrent degradation and self-healing in perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 7, 11574 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11574

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51675210 and 51675209) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2016M602283). We thank the Analytical and Testing Center of Huazhong University of Science and Technology for the field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM). We also thank the assistance from Prof. Hongwei Han and Dr. Miao Duan at Michael Grätzel Center for Mesoscopic Solar Cells of Huazhong University of Science and Technology for the time-resolved photoluminescence measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Sun, B., Liu, X. et al. Efficient Carbon-Based CsPbBr3 Inorganic Perovskite Solar Cells by Using Cu-Phthalocyanine as Hole Transport Material. Nano-Micro Lett. 10, 34 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-018-0187-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-018-0187-3