Abstract

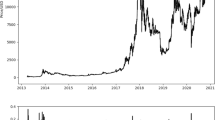

The phenomenal rise in the price of bitcoin, prior to the trend reversal of early 2018, resembles a bubble as spectacular as any other bubble. A mere observation of the price rise and a comparison with the common characteristics of a bubble provide anecdotal evidence for the bitcoin bubble. Based on price and volume data up to the end of November 2017, formal empirical evidence is presented by using procedures that do not require the estimation of a fundamental value for bitcoin. The empirical evidence shows that (i) the volume of trading can be explained predominantly in terms of price dynamics; (ii) trading in bitcoin is based exclusively on technical considerations pertaining to past price movements, particularly positive price changes; and (iii) the price of bitcoin is an explosive process. These findings are interpreted to imply a price bubble.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This is quite a contrast in views but it seems more plausible to suggest that bubbles can be identified as they form.

Naturally, it would be interesting to find out why those who have done their work do not think that pure speculation is responsible for bitcoin’s price rise.

This is what is known in the behavioural finance literature as a “bubble followed by a crash”. The phenomenon is triggered by inefficiencies, such as under-reaction and over-reactions to the arrival of new information. See, for example, Moosa and Ramiah (2017).

Some economists believe that rationality precludes the possibility of bubbles. In an interview with John Cassidy, Eugene Fama rejected the very notion of bubble, suggesting that he did not even know what a bubble meant (Cassidy 2010). He added that he became so tired of seeing the word “bubble” in The Economist that he did not renew his subscription.

It is unlikely that the bubble is correlated with fundamentals because fundamentals do not change at an explosive rate. Dividends are fairly stable and, apart from exceptional circumstances such as hyperinflation, macroeconomic fundamentals move slowly. One of the main points raised by the proponents of behavioural finance is their denial of the possibility of significant changes in valuation. For example, Shiller (2000) concludes that stock prices move in excess of changes in valuation.

There is also the problem that different tests of cointegration provide different results—see, for example, Moosa (2017).

Perhaps the current mining rules are so strict by design to induce scarcity and buying frenzy.

Metcalfe’s law states that the value of a telecommunications network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users of the system. .

Gandal et al. (2018) find that by driving up the transaction volume, one or two traders managed to manipulate the price of bitcoin, pushing it up by some 700% in 2013. This kind of increase in volume cannot be considered a rise in the value of bitcoin.

Perhaps the word “causes” should be replaced with “associated with” because there is no evidence for a causal relation.

Whenever a successful Ponzi scheme emerges, and just before it is recognized as being so, entrepreneurs try to emulate it. As of January 2018 some 1384 cryptocurrencies exist (and still counting). According to The Economist (2018), “a new crypto-currency is born almost daily” with fascinating names such as UFO Coin, PutinCoin, sexcoin and InsaneCoin.

The data were obtained from https://data.bitcoinity.org/markets/price_volume/all/USD?t=lb&vu=curr.

While nothing is special about 2015, the objective here is to demonstrate that the bubble still shows when the extremely high prices recorded in 2017 are not measured relative to the low levels of 2010 but rather to the subsequent higher prices.

It was stated earlier that cointegration is not a valid test for bubbles, but that is only because the stationary residual is considered to be the bubble component. Here, it is different because it is not claimed that the residual of Eq. (5) is the bubble component. Rather, the objective is to show that a bubble may be indicated by a close relation between volume and price dynamics.

References

Adalid, R., & Detken, C. (2007). Liquidity shocks and asset price booms and bust cycles. ECB Working Papers, No. 732.

Alabi, K. (2017). Digital blockchain networks appear to be following Metcalfe’s law. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications,24, 23–29.

Baek, C., & Elbeck, M. (2015). Bitcoins as an investment or speculative vehicle? A first look. Applied Economics Letters,22, 30–34.

Bariviera, A. F., Basgall, M. J., Hasperué, W., & Naiouf, M. (2017). Some stylized facts of the bitcoin market. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications,484, 82–90.

Blanchard, O. J., & Watson, M. W. (1982). Bubbles, rational expectations and financial markets. NBER Working Papers, No 945.

Blau, B. M. (2017). Price dynamics and speculative trading in bitcoin. Research in International Business and Finance,41, 493–499.

Byrne, P. (2017). The problem with calling bitcoin a “Ponzi Scheme”, 8 December. https://prestonbyrne.com/2017/12/08/bitcoin_ponzi/. Accessed 5 Jan 2018.

Cassidy, J. (2010). After the blowup: Laissez–Faire economists do some soul-searching—And finger-pointing, 11 January. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/01/11/after-the-blowup. Accessed 23 Jan 2018

Cheah, E. T., & Fry, J. (2015). Speculative bubbles in bitcoin markets? An empirical investigation into the fundamental value of bitcoin. Economics Letters,130, 32–36.

Cheung, A. W. K., Roca, E., & Su, J. J. (2015). Crypto-currency bubbles: an application of the Phillips, Shi and Yu (2013) methodology on Mt. Gox bitcoin prices. Applied Economics,47(23), 2348–2358.

Corbet, S., Lucey, B., & Yarovaya, L. (2017). Datestamping the bitcoin and ethereum bubbles. SRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3079712 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3079712. Accessed 16 Jan 2018.

Detrixhe, J. (2017). Irrational exuberance, 5 September. https://qz.com/1067557/robert-shiller-wrote-the-book-on-bubbles-he-says-the-best-example-right-now-is-bitcoin/. Accessed 5 Dec 2017.

Diba, B., & Grossman, H. (1988). Explosive rational bubbles in stock prices. American Economic Review,78, 520–530.

Eichenwald, K. (2013). The logic problems that will eventually pop the bitcoin bubble, April. https://www.vanityfair.com/news/politics/2013/04/logic-problems-bitcoin-bubble. Accessed 5 Jan 2018.

Flood, R., Hodrick, R., & Kaplan, P. (1994). An evaluation of recent evidence on stock price bubbles. In R. Flood & P. Garber (Eds.), Speculative bubbles, speculative attacks, and policy switching. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press.

Frankel, J., & Froot, K. (1990). The rationality of the foreign exchange rate: Chartists, fundamentalists and trading in the foreign exchange market. American Economic Review,80, 181–185.

Gandal, N., Hamrick, J. T., Moore, T., & Oberman, T. (2018). Price manipulation in the bitcoin ecosystem. Journal of Monetary Economics, 95, 86–96.

Gannon, W. (2017). Analyzing the media coverage of bitcoin—November monthly media review with the AYLIEN news API, 7 December. http://blog.aylien.com/analyzing-the-media-coverage-of-bitcoin-november-monthly-media-review-with-the-aylien-news-api/. Accessed 8 Jan 2018.

Garcia, D., Tessone, C. J., Mavrodiev, P., & Perony, N. (2014). The digital traces of bubbles: Feedback cycles between socio-economic signals in the bitcoin economy. Journal of the Royal Society, Interface,11, 20140623.

Gürkaynak, R. S. (2005). Econometric tests of asset price bubbles: Taking stock. Division of Monetary Affairs Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Washington, DC. https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2005/200504/200504pap.pdf. Accessed 7 Dec 2017.

Harvey, A. C. (1989). Forecasting, structural time series models and the Kalman filter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jacobs, S. (2018). Credit Suisse says bitcoin’s fair value is almost half its current price, 18 January. https://www.businessinsider.com.au/bitcoin-fair-value-2018-1. Accessed 20 Jan 2018.

Kindleberger, C., & Aliber, R. Z. (1996). Manias, panics, and crashes: a history of financial crises (4th ed.). Hoboken (NJ): Wiley.

Koopman, S. J., Harvey, A. C., Doornik, J. A., & Shephard, N. (2006). Structural time series analyser, modeller and predictor. London: Timberlake Consultants Ltd.

Kristoufek, L. (2015). What are the main drivers of the bitcoin price? Evidence from wavelet coherence analysis. PLoS ONE,10(4), e0123923.

LeRoy, S., & Porter, R. (1981). The present-value relation: Tests based on implied variance bounds. Econometrica,49, 555–574.

Moosa, I. A. (2017). Econometrics as a con art: Exposing the limitations and abuses of econometrics. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Moosa, I. A., & Ramiah, V. (2017). The financial consequences of behavioural biases: An analysis of bias in corporate finance and financial planning. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan (Springer Nature).

Morris, C. (2017). Some bitcoin investors are mortgaging their homes to buy more digital currency, 12 December. http://fortune.com/2017/12/12/bitcoin-investors-mortgages/. Accessed 20 Jan 2018.

Morrison, R. (2017). The bitcoin bubble, 20 December. https://www.globalresearch.ca/the-bitcoin-bubble/5623349. Accessed 20 Jan 2018.

Phillips, P. C. B., Wu, Y., & Yu, J. (2011). Explosive behavior in the 1990s NASDAQ: When did exuberance escalate asset values? International Economic Review,52, 201–226.

Phillips, P. C. B., & Yu, J. (2011). Dating the timeline of financial bubbles during the subprime crisis. Quantitative Economics,2, 455–491.

Ratner, J. (2017). When your cab driver starts talking about bitcoin, it’s time to sell, 12 December. http://business.financialpost.com/technology/blockchain/when-your-cab-driver-starts-talking-about-bitcoin-its-time-to-sell. Accessed 21 Jan 2018

Reynolds, M. (2017). Psychology explains why your friends can’t shut up about bitcoin, 11 December. http://www.wired.co.uk/article/will-bitcoin-bubble-burst-or-crash-2017-psychology-cryptocurrency-economics. Accessed 5 Jan 2018.

Rothchild, J. (1996). When the shoeshine boys talk stocks it was a great sell signal in 1929, so what are the shoeshine boys talking about now? 15 April. http://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/1996/04/15/211503/index.htm. Accessed 20 Dec 2017.

Shah, S. (2017). People are mortgaging their houses to buy bitcoin, 12 December. https://www.engadget.com/2017/12/12/bitcoin-mania-mortage-house-investors/. Accessed 16 Jan 2018.

Shiller, R. (1981). Do stock prices move too much to be justified by subsequent changes in dividends? American Economic Review,71, 421–436.

Shiller, R. J. (2000). Irrational exuberance (1st ed.). Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press.

Shiller, R. J. (2002). Bubbles, human judgment, and expert opinion. Financial Analysts Journal,58, 18–26.

Shiller, R. J., Fischer, S., & Friedman, B. M. (1984). Stock prices and social dynamics. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity,2, 457–510.

Silverstein, S. (2017). Analyst says 94% of bitcoin’s price movement over the past four years can be explained by one equation, 11 November. https://www.businessinsider.com.au/bitcoin-price-movement-explained-by-one-equation-fundstrat-tom-lee-metcalf-law-network-effect-2017-10. Accessed 6 Jan 2018.

Suberg, W. (2017). Charles Schwab chief strategist: Bitcoin’s bubble is ‘something different’, 26 December. https://cointelegraph.com/news/charles-schwab-chief-strategist-bitcoins-bubble-is-something-different. Accessed 10 Jan 2018.

The Economist (2018) Crypto-currencies: Beyond bitcoin, 13 January (pp. 64–65).

Thompson, D. (2017). Is bitcoin the most obvious bubble ever? 9 December. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/12/bitcoin-bubble/547952/. Accessed 5 Jan 2018.

Tomfort, A. (2017). Detecting asset price bubbles: A multifactor approach. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues,7, 46–55.

Turanova, G. (2017). Is bitcoin a bubble? 29 December. http://www.nasdaq.com/article/is-bitcoin-a-bubble-cm898150. Accessed 14 Jan 2018.

Volpicelli, G. (2017). If the bitcoin bubble bursts, this is what will happen next, 21 December. http://www.wired.co.uk/article/what-happens-when-the-bitcoin-bubble-pops. Accessed 15 Jan 2018.

Wasik, J. (2017). Four ways a bitcoin bubble plays out, 11 December. https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnwasik/2017/12/11/four-ways-a-bitcoin-bubble-plays-out/#41f726c2639c. Accessed 15 Jan 2018.

West, K. (1987). A specification test for speculative bubbles. Quarterly Journal of Economics,102, 553–580.

Wu, Y. (1997). Rational bubbles in the stock market: Accounting for the U.S. stock-price volatility. Economic Inquiry,35, 309–319.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moosa, I.A. The bitcoin: a sparkling bubble or price discovery?. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 47, 93–113 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40812-019-00135-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40812-019-00135-9