Abstract

Purpose of Review

Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that participates in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) during development and under homeostatic conditions. IFN-γ also plays a key pathogenic role in several diseases that affect hematopoiesis including aplastic anemia, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, and cirrhosis of the liver.

Recent Findings

Studies have shown that increased IFN-γ negatively affects HSC homeostasis, skewing HSC towards differentiation over self-renewal and eventually causing exhaustion of the HSC compartment.

Summary

Here, we explore the mechanisms by which IFN-γ regulates HSC in both normal and pathological conditions. We focus on the role of IFN-γ signaling in HSC fate decisions, and the transcriptional changes it elicits. Elucidating the mechanisms through which IFN-γ regulates HSCs may lead to new therapeutic options to prevent or treat adverse hematologic effects of the many diseases to which IFN-γ contributes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Homeostatic production of blood and immune cells by hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPC) in the bone marrow (BM) is necessary to support tissue oxygenation and immunity (Fig. 1a). Recent developments in hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) research have shown that inflammatory cytokines can affect blood production by the bone marrow. HSCs express cytokine receptors and pattern-recognition receptors (PRR) and can directly respond to pro-inflammatory cytokines and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [1,2,3,4]. These observations have led to a new understanding of the role of both tonic and stress inflammatory signals in regulation and homeostasis of the HSC pool.

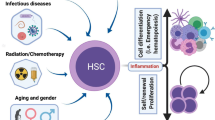

The self-renewal and differentiation equilibrium of HSCs in their niche. a Steady-state hematopoiesis is a balance between HSC self-renewal and differentiation. Cues from the niche regulate this balance to maintain HSC quiescence and self-renewal capabilities while contributing to the production of differentiated immune and blood cells. b IFN-γ signaling alters hematopoiesis and niche cues by inducing myeloid-biased HSC differentiation at the expense of self-renewal and differentiation to the lymphoid and erythroid lineages. IFN-γ also suppresses HSC self-renewal either directly or by contributing to changes in niche cells such as production of more macrophages and induction of IL-6 production by MSCs

Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) is a type II interferon secreted by T cells and NK cells during Th1-mediated immune responses. IFN-γ functions as a pro-inflammatory cytokine that mediates antimicrobial, antiviral, and antitumor responses by activating effector immune cells and enhancing antigen presentation [5]. This cytokine is known to play a role in a number of diseases in which HSPCs are impaired including aplastic anemia, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), cirrhosis of the liver, and many infectious diseases such as HIV, mycobacterial infections, and hepatitis C [4, 6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Recent studies have shown that IFN-γ can affect HSCs at multiple levels, ranging from their development, quiescence, and differentiation, to the niche cells that support them [16•, 17•, 18••, 19•, 20,21,22, 23•, 24••, 25, 26••]. Increasing our understanding of how IFN-γ regulates HSCs may identify pathways to improve homeostasis of the hematopoietic system and immunity during inflammatory stress.

In this review, we summarize the effects of IFN-γ on HSC development, homeostasis, and fate. We focus on the influence of IFN-γ signaling on HSC differentiation and how it can lead to irreversible HSC depletion.

IFN-γ Signaling in HSC Development

In vertebrates, HSCs arise from endothelial cells (EC) in hemogenic areas such as the aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) region of the embryo [17•, 27]. The signaling pathways promoting HSC emergence are largely shared across different vertebrates [17•, 28]. Studies have shown that the mechanical forces from blood flow are necessary for HSC emergence [17•, 27, 29, 30]. Blood flow induces the expression of IFN-γ, IFN-γ receptor (IFNγR), and Runx1 [17•, 29], an essential regulator of the EC-to-HSC transition [31] and HSC emergence [27]. ECs in the AGM respond to IFN-γ, leading to downstream signaling through the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) [17•] to promote the expression of genes responsible for the EC-to-HSC transition. Several groups have demonstrated that sterile tonic inflammatory signaling is required for HSC emergence [16•, 17•, 32,33,34,35, 36•]. Thus, IFN-γ signaling through non-canonical STAT3 activation is required for normal HSC development at the embryonic stage.

IFN-γ and the Cell Cycle

The importance of IFN-γ signaling in HSCs is not limited to their development. Recent evidence has shown that IFN-γ regulates HSC cell cycle activity. Baldridge et al. reported that HSCs are stimulated to proliferate during Mycobacterium avium infection via an IFN-γ-dependent mechanism, and a similar phenomenon has also been demonstrated during Ehrlichia muris infection [20, 22]. Type I interferons (IFN-α and IFN-β) similarly induce HSCs to exit from dormancy [20, 37]. In contrast, another study indicated that IFN-γ reduces HSC proliferation in vivo and that in vitro culturing of HSCs with IFN-γ did not induce HSCs to come out of quiescence [38]. While some have suggested that these conflicting findings might be explained by Sca-1 induction by interferon in myeloid progenitor cells (which normally do not express this marker and can thus be falsely reported as HSCs [18••, 22, 23•, 39]), the induction of HSC proliferation in response to IFN-γ has since been documented using a range of different surface markers and avoiding Sca-1 as an HSC marker. Differences in experimental conditions are more likely to explain the different conclusions of these studies, as we discuss below. Furthermore, inflammation-dependent activation of HSC proliferation has been confirmed using methods that do not depend on cell surface marker expression [1, 37]. Altogether, the accumulated evidence indicates that IFN-γ induces HSCs to exit their quiescent state.

IFN-γ and Cell Fate

Apoptosis

While the short-term effects of IFN-γ signaling are characterized by an increase in HSC proliferation, the long-term effects appear to be deleterious, leading to HSC depletion and exhaustion. Interferons are well known to trigger apoptosis in many cell types including cancer cells [40,41,42] and whether IFN-γ directly induces HSC apoptosis has been intensely debated. In vitro IFN-γ stimulation of human CD34+ HSCs co-cultured with stromal cells increased HSC apoptosis [43]. Furthermore, transcriptional profiling of HSCs from patients with high IFN-γ levels have indicated transcriptional signatures of apoptosis [44]. However, more recently, cultured primitive HSCs stimulated with IFN-γ showed no increase in apoptosis [20]. Additionally, mice infected with M. avium or directly treated with IFN-γ did not show increased HSC apoptosis, although these cells were more sensitive to undergo apoptosis after a secondary stress [18••]. This sensitization to apoptosis has also been reported upon stimulation with other pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-α [39]. Indeed, HSC exit from the quiescent state in response to either IFN-α or IFN-γ is accompanied by increased DNA damage [1, 37, 45], thus providing a possible explanation by which the threshold for apoptosis is lowered. Strikingly, HSC apoptosis increases in pro-inflammatory diseases concurring with high levels of IFN-γ in the circulation, such as aplastic anemia (AA) [4, 44]. However, IFN-γ is not the only cytokine that is upregulated in these diseases. IFN-γ signaling in AA stimulates T cells to produce TNF-α and RANKL [46], two molecules known to promote apoptosis. Similarly, in patients with liver cirrhosis, blood levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 also increase, whereas the total number of CD34+ HSCs decreases in proportion to disease severity [8]. Interestingly, in a mouse model of lymphochoriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection, IFN-γ signaling resulted in overall reduced BM cellularity [19•, 38]. LCMV infection induces the production of multiple cytokines, including IFN-α, IL-1, and IL-6, in addition to IFN-γ, and has been reported to induce NLRP1 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis of hematopoietic progenitor cells [47, 48]. Altogether, these studies suggest that IFN-γ only triggers HSC apoptosis in the presence of other stress stimuli.

Consistent with this theme, Chen et al. showed that IFN-γ induces the expression of Fas and pro-apoptotic caspases in HSPC; however, in this study, the HSPCs only underwent apoptosis when cultured with activated cytotoxic T cells [26••]. Fas upregulation has similarly been described in human CD34+ HSCs from AA patients [44] who also have autoreactive T cells that express FasL, contributing to the pathogenesis of AA and risk of bone marrow failure. Given the apparent requirement of additional cytokines for HSC apoptosis, the conflicting data between in vitro studies showing induction of apoptosis and in vivo studies showing no apoptosis is likely explained by the fact that taking HSCs out of their in vivo niche can be a primary stress by itself [18••]. Thus, by removing the cues that promote HSC maintenance, in vitro studies of cytokine stimulation inherently involve multiple stressors, and stimulation with IFN-γ, in addition to the stress of being outside the niche, can push HSCs into apoptosis. These observations indicate that IFN-γ does not directly induce apoptosis in HSCs, but rather that a combination of cytokines and stressors along with IFN-γ signaling can activate a pro-apoptotic response.

Differentiation Versus Self-Renewal

In steady-state hematopoiesis, dividing HSCs either self-renew or differentiate. This balance allows for the maintenance of HSC numbers concomitantly with the production of necessary hematopoietic cells. However, IFN-γ signaling can alter this balance and push HSCs towards differentiation at the expense of self-renewal. Chen et al. showed that IFN-γ signaling downregulates Gata2 and Ets-1 expression in HSCs [26••]. These genes enforce HSC homeostasis, whereas decreased expression promotes differentiation [49, 50]. At the same time, IFN-γ signaling through STAT1 activates the expression of interferon regulatory factors (IRF) that can promote differentiation towards the myeloid lineage. For example, IRF1 activates PU.1, a master regulator of myeloid-promoting genes [51,52,53]. IFN-γ may also alter HSC differentiation by differential recruitment of lineage-biased HSC subtypes. Studies using LCMV showed that an HSC subtype biased towards the myeloid lineage (My-HSC) is preferentially recruited to differentiate at an accelerated rate in response to IFN-γ through the activation of Cebpb [19•], a transcription factor that promotes myeloid differentiation [54]. Infection-induced IFN-γ signaling promotes myelopoiesis in animal models of Ehrlichia chaffeensis and M. avium infection [19•, 21] as well as in vaccination with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) [55••]. Furthermore, BCG vaccination reprograms HSCs to give rise to epigenetically altered macrophages with increased efficacy against TB infection [55••]. We previously conducted RNA sequencing analysis on purified HSCs from M. avium-infected mice to identify the drivers of differentiation during chronic infection [18••]. This study identified Batf2, also known as suppressor of AP-1, regulated by interferon (SARI), as an important mediator of myeloid differentiation. Deletion of Batf2 interfered with myeloid differentiation both in mice infected with M. avium and human CD34+ HSCs stimulated with IFN-γ [18••]. Overall, these studies indicate that IFN-γ can drive gene expression changes in HSCs that promote their differentiation towards the myeloid lineage (Fig. 1b).

IFN-γ signaling also interferes with HSC self-renewal by upregulating the expression of the suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) [56], which in turn inhibits STAT5 phosphorylation [38]. Thrombopoietin (TPO), a hematopoietic growth factor, is required to maintain HSC self-renewal properties through the activation of STAT5 after engaging its receptor c-MPL [57, 58]. Thus, by suppressing Stat5, IFN-γ impairs TPO signaling and thereby diminishes HSC self-renewal and reconstituting capabilities. Collectively, these observations show that IFN-γ promotes terminal differentiation directed by myeloid-promoting genes while simultaneously suppressing self-renewal pathways. These signaling changes provide insight into the potential mechanisms by which chronic IFN-γ stimulation depletes the HSC pool (Fig. 1b).

Autophagy and Regulation of IFN-γ Responses

Autophagy has been described as an essential mechanism by which HSCs can survive nutrient deprivation and metabolic stress [59]. Interestingly, short-term IFN-γ signaling has been shown to induce expression of the autophagy-related p47 GTPase Irgm1 in HSCs. Irgm1-deficient mice demonstrate impaired autophagy flux in HSCs and a hyperproliferative phenotype associated with an expression signature of excessive IFN signaling [60]. These data suggest that autophagy can have a variety of context-specific roles in HSCs and may promote HSC longevity through regulation of IFN-γ signaling.

IFN-γ and the HSC Niche

HSC homeostasis and maintenance are dependent on the tightly regulated microenvironment in which they reside. This microenvironment, or niche, is composed of multiple cell types including osteoblasts, endothelial cells, mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC), nerve fibers, and hematopoietic cells such as megakaryocytes and monocytes [61,62,63,64] which collectively provide an environment suitable for HSC homeostasis and survival. IFN-γ signaling alters these interactions. For example, HSPCs interact with their surrounding cells through expression of cell surface integrins. IFN-γ affects signaling by αvβ3 (CD51/CD61), an integrin that, in conjunction with TPO, promotes HSC maintenance, quiescence, and long-term repopulating activity in steady-state conditions [65, 66]. In the presence of IFN-γ stimulation, integrin αvβ3 signaling suppresses HSCs and causes a loss of long-term repopulating activity [25, 67]. These findings demonstrate that IFN-γ can change the outcome of integrin αvβ3 signaling from HSC maintenance to suppression.

IFN-γ affects several cells in the niche that maintain HSC homeostasis. Osteoblasts in the niche promote HSC maintenance through Notch signaling as well as through FasL-induced osteoclast apoptosis [62, 68, 69]. IFN-γ increases T cell production of TNFα and RANKL, which suppress osteoblast FasL expression, inducing bone resorption through increased osteoclast function [46, 68, 70]. In this process, T cell-produced TNF-α serves as a positive feedback loop that further downregulates osteoblastic FasL [68, 70], thus perpetuating a decline in osteogenesis and damage to the HSC niche. Similarly, type I interferons have been reported to damage the function of vascular endothelial cells, a critical component of the HSC niche [71]. Whether type II interferon leads to harmful effects on vascular endothelium in the HSC niche remains to be determined.

MSCs are another key cell type in the HSC niche affected by IFN-γ. MSCs have an important role in HSC maintenance and homeostasis through the production of CXCL12 and stem cell factor (SCF) [62, 72] (Fig. 1a). However, during acute viral infections, IFN-γ produced by cytotoxic T cells stimulates MSC to secrete IL-6 [23•], which is known to skew myeloerythroid differentiation towards myeloid cells [73]. Studies in human BM from AA patients also showed increased expression of IL-6 in stromal cells [44]. Thus, IL-6 signaling, acting downstream of IFN-γ, proves to be yet another cue that pushes HSCs to differentiate (Fig. 1b). Megakaryocytes have been shown to promote quiescence and HSC maintenance through the production of CXCL4 and TGFβ1 [74, 75]. However, megakaryocytes may also promote HSC proliferation during myeloablative stress by secreting fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1) [74], opening the possibility of a regulatory role for megakaryocytes in promoting HSC differentiation during immunological stress.

The cellular composition of the niche may also be altered by IFN-γ. McCabe et al. demonstrated that macrophages are negative regulators of HSCs and that IFN-γ signaling promotes HSC suppression by increasing the number of macrophages in the BM [24••] (Fig. 1b). While the mechanisms by which macrophages suppress HSC have not yet been described, a recent paper showed that histamine produced by myeloid-derived cells in the niche promotes HSC quiescence [76••]. These data show that the composition of cell types in the bone marrow niche can exert feedback regulation on HSC behavior. Altogether, the current literature shows that IFN-γ can indirectly affect HSC fate by altering both the function and composition of niche cells.

IFN-γ in Disease Pathogenesis

While IFN-γ signaling has an important role in HSC embryonic development and homeostasis, it also contributes to the pathogenesis of several diseases. Patients suffering from AA have dysregulated autoreactive T cells, increased blood levels of IFN-γ, and HSC loss likely due to the loss of self-renewal properties [4, 9]. Differentiation of multipotent progenitors (MPP) to granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (GMP) and megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEP) is also impaired in AA patients by intrinsic IFN-γ inhibition of hematopoiesis [9]. Polymorphisms in intronic regions of IFN-γ transcripts that increase the transcript’s stability and half-life have been correlated with a higher risk of developing AA [77], supporting the observation that prolonged IFN-γ exposure impairs HSC function. Blood levels of IFN-γ are also increased in liver cirrhosis patients, who can develop a cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction syndrome characterized by impaired hematopoiesis and immunity. It stands to reason that the deleterious effects of persistent inflammation as described above contribute to the hematologic and immuneologic dysfunction seen in these patients [8]. IFN-γ is also a driver of pathogenesis in patients with HLH, a hematological disorder characterized by impaired lymphocyte cytotoxic function and hyperproduction of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and M-CSF, along with IFN-γ [6, 11]. IFN-γ signaling downregulates CD47-SIRPA anti-phagocytic signals, leading to increased hemophagocytosis, anemia, and destruction of HSCs by macrophages [6, 7].

HSC homeostasis is also altered during immune responses against infectious diseases that promote the production of high levels of IFN-γ. Chronic infections such as HIV or tuberculosis, while disparate in nature, both lead to BM suppression [10]. Until recently, the etiology of BM suppression during HIV or tuberculosis have been poorly understood. However, recent studies using mouse models of M. avium or viral infection have shown that altered hematopoiesis during these infections can be attributable to the IFN-γ-mediated immune response. For example, chronic M. avium infection leads to IFN-γ-dependent irreversible loss of HSC self-renewal and engraftment capabilities, and cytopenias [18••]. Collectively, these studies elucidate the role of IFN-γ in the progression and pathogenesis of diseases that result in HSC suppression.

Conclusions

In summary, IFN-γ signaling can affect HSC homeostasis directly by altering gene expression in HSCs and indirectly by altering the regulatory roles of neighboring niche cells. Collectively, the studies reviewed here show that short-term IFN-γ signaling induces HSC proliferation, whereas long-term stimulation promotes HSC differentiation and impaired self-renewal. Excessive replicative stress and bias towards terminal differentiation leads to HSC loss during chronic IFN-γ stimulation. Additionally, although IFN-γ alone might be insufficient to trigger HSC apoptosis in the absence of secondary stimulation or stress, IFN-γ sensitizes HSCs to undergo apoptosis [18••, 20, 26••, 44].

Whereas IFN-γ has been implicated in changing the HSC niche and ultimately causing irreversible damage to HSCs [2, 18••, 78], the long-term effects of chronic inflammation in the HSC niche remain unknown. Therefore, whether the loss of HSC self-renewal capabilities is completely or partially due to niche damage remains an important question. The mechanisms by which changes in specific niche cell types (e.g., macrophages) during inflammation alter hematopoiesis remain poorly defined. Answering these questions will expand our understanding of HSC and bone marrow recovery following chronic inflammation.

Finally, the studies reviewed above show that IFN-γ activates HSC differentiation and the subsequent production of myeloid effector cells. Understanding the kinetics of inflammation-induced HSC differentiation could open new opportunities to exploit the therapeutic properties of HSCs and their progeny. Additionally, defining the cues that promote differentiation over self-renewal after IFN-γ stimulation may elucidate potential therapeutic targets in chronic inflammatory diseases that could protect patients against HSC exhaustion and bone marrow failure.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Takizawa H, Boettcher S, Manz MG. Demand-adapted regulation of early hematopoiesis in infection and inflammation. Blood. 2012;119:2991–3002.

Esplin BL, Shimazu T, Welner RS, Garrett KP, Nie L, Zhang Q, et al. Chronic exposure to a TLR ligand injures hematopoietic stem cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:5367–75.

Burberry A, Zeng MY, Ding L, Wicks I, Inohara N, Morrison SJ, et al. Infection mobilizes hematopoietic stem cells through cooperative NOD-like receptor and toll-like receptor signaling. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:779–91.

Smith JNP, Kanwar VS, Macnamara KC, Baldridge MT. Hematopoietic stem cell regulation by type I and II interferons in the pathogenesis of acquired aplastic anemia. Front Immunol. 2016;7:1–13.

Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T, Hume DA. Interferon-y: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:163–89.

Zoller EE, Lykens JE, Terrell CE, Aliberti J, Filipovich AH, Henson PM, et al. Hemophagocytosis causes a consumptive anemia of inflammation. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1203–14.

Kuriyama T, Takenaka K, Kohno K, Yamauchi T, Daitoku S, Yoshimoto G, et al. Engulfment of hematopoietic stem cells caused by down-regulation of CD47 is critical in the pathogenesis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis engulfment of hematopoietic stem cells caused by down-regulation of CD47 is critical in the pathogenesis of hemo. Blood. 2012;120:4058–67.

Bihari C, Anand L, Rooge S, Kumar D, Saxena P, Shubham S, et al. Bone marrow stem cells and their niche components are adversely affected in advanced cirrhosis of the liver. Hepatology. 2016;64:1273–88.

Lin F, Karwan M, Saleh B, Hodge DL, Chan T, Boelte KC, et al. IFN-γ causes aplastic anemia by altering hematopoietic stem / progenitor cell composition and disrupting lineage differentiation. Blood. 2014;124:3699–708.

Leguit RJ, Van Den Tweel JG. The pathology of bone marrow failure. Histopathology. 2010;57:655–70.

Jordan MB, Hildeman D, Kappler J, Marrack P. An animal model of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): CD8 + T cells and interferon gamma are essential for the disorder. Immunobiology. 2004;104:735–43.

Koka PS, Reddy ST. Cytopenias in HIV infection: mechanisms and alleviation of hematopoietic inhibition. Curr HIV Res. 2004;2:275–82.

Gilbertson B, Zhong J, Cheers C. Anergy, IFN-gamma production, and apoptosis in terminal infection of mice with Mycobacterium avium. J Immunol. 1999;163:2073–80.

Wang J, Yin Y, Wang X, Pei H, Kuai S, Gu L, et al. Ratio of monocytes to lymphocytes in peripheral blood in patients diagnosed with active tuberculosis. Braz J Infect Dis. 2015;19:125–31.

Brown KE, Tisdale J, Barrett AJ, Dunbar CE, Young NS. Hepatitis-associated aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1059–64.

• Li Y, Esain V, Teng L, Xu J, Kwan W, Frost IM, et al. Inflammatory signaling regulates embryonic hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell production. Genes Dev. 2014;28:2597–612. The results highlight the importance of IFN-γ signaling in HSC emergence.

• Sawamiphak S, Kontarakis Z, Stainier DYR. Interferon gamma signaling positively regulates hematopoietic stem cell emergence. Dev Cell. 2014;31:640–53. The results highlight the importance of IFN-γ signaling in HSC emergence.

•• Matatall KA, Jeong M, Chen S, Sun D, Chen F, Mo Q, et al. Chronic infection depletes hematopoietic stem cells through stress-induced terminal differentiation. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2584–95. The authors show that terminal differentiation is the cause of HSC depletion during chronic infection.

• Matatall KA, Shen CC, Challen GA, King KY. Type II interferon promotes differentiation of myeloid-biased hematopoietic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2014;32:3023–30. This publications showes the selective recruitment of lineage-biased HSCs during IFN-γ signaling.

Baldridge MT, King KY, Boles NC, Weksberg DC, Goodell MA. Quiescent haematopoietic stem cells are activated by IFN-γ in response to chronic infection. Nature. 2010;465:793–7.

MacNamara KC, Oduro K, Martin O, Jones DD, McLaughlin M, Choi K, et al. Infection-induced myelopoiesis during intracellular bacterial infection is critically dependent upon IFN-γ signaling. J Immunol. 2011;186:1032–43.

MacNamara KC, Jones M, Martin O, Winslow GM. Transient activation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells by IFNγ during acute bacterial infection. PLoS One. 2011;6:1–9.

• Schürch CM, Riether C, Ochsenbein AF. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells stimulate hematopoietic progenitors by promoting cytokine release from bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:460–72. Demostrastes the indirects effects of IFN-γ on HSCs.

•• McCabe A, Zhang Y, Thai V, Jones M, Jordan MB, MacNamara KC. Macrophage-lineage cells negatively regulate the hematopoietic stem cell pool in response to interferon gamma at steady state and during infection. Stem Cells. 2015;33:2294–305. Provides evidence of the regulatory roles of niche cells and their response to IFN-γ.

Umemoto T, Matsuzaki Y, Shiratsuchi Y, Hashimoto M, Nakamura-ishizu A, Petrich B, et al. Integrin αvβ3 enhances the suppressive effect of interferon-γ on hematopoietic stem cells. EMBO J. 2017;36:2390–403.

•• Chen J, Feng X, Desierto MJ, Keyvanfar K, Young NS. IFN-γ-mediated hematopoietic cell destruction in murine models of immune-mediated bone marrow failure. Blood. 2015;126:2621–31. This article shows evidence of the detrimental effects of IFN-γ in HSCs.

Boisset J, Van Cappellen W, Andrieu-soler C, Galjart N, Dzierzak E, Robin C. In vivo imaging of haematopoietic cells emerging from the mouse aortic endothelium. Nature. 2010;464:116–20.

Clements WK, Traver D. Signalling pathways that control vertebrate haematopoietic stem cell specification. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:336–48.

Adamo L, Naveiras O, Wenzel PL, McKinney-Freeman S, Mack PJ, Gracia-Sancho J, et al. Biomechanical forces promote embryonic haematopoiesis. Nature. 2009;459:1131–5.

North TE, Goessling W, Peeters M, Li P, Ceol C, Lord AM, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell development is dependent on blood flow. Cell. 2009;137:736–48.

Chen MJ, Yokomizo T, Zeigler BM, Dzierzak E, Speck NA. Runx1 is required for the endothelial to haematopoietic cell transition but not thereafter. Nature. 2009;457:887–91.

Espín-Palazón R, Stachura DL, Campbell CA, García-Moreno D, Del Cid N, Kim AD, et al. Proinflammatory signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell emergence. Cell. 2014;159:1070–85.

Stachura DL, Svoboda O, Campbell CA, Espín-Palazón R, Lau RP, Zon LI, et al. The zebrafish granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (Gcsfs): 2 paralogous cytokines and their roles in hematopoietic development and maintenance. Blood. 2013;122:3918–28.

Robin C, Ottersbach K, Durand C, Peeters M, Vanes L, Tybulewicz V, et al. An unexpected role for IL-3 in the embryonic development of hematopoietic stem cells. Dev Cell. 2006;11:171–80.

Orelio C, Haak E, Peeters M, Dzierzak E. Interleukin-1-mediated hematopoietic cell regulation in the aorta-gonad-mesonephros region of the mouse embryo. Blood. 2008;112:4895–904.

• Pietras EM. Inflammation: a key regulator of hematopoietic stem cell fate in health and disease. Blood. 2017;130:1693–8. A review of the roles of multiple inflammatory cytokines in HSC fate

Essers MAG, Offner S, Blanco-Bose WE, Waibler Z, Kalinke U, Duchosal MA, et al. IFNα activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature. 2009;458:904–8.

de Bruin AM, Demirel Ö, Hooibrink B, Brandts CH, Nolte MA. Interferon-γ impairs proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Blood. 2013;121:3578–85.

Pietras EM, Lakshminarasimhan R, Techner J-M, Fong S, Flach J, Binnewies M, et al. Re-entry into quiescence protects hematopoietic stem cells from the killing effect of chronic exposure to type I interferons. J Exp Med. 2014;211:245–62.

Senegas A, Villard O, Neuville A, Marcellin L, Pfaff AW, Steinmetz T, et al. Toxoplasma gondii-induced foetal resorption in mice involves interferon-γ-induced apoptosis and spiral artery dilation at the maternofoetal interface. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:481–7.

Inagaki Y, Yamagishi SI, Amano S, Okamoto T, Koga K, Makita Z. Interferon-γ-induced apoptosis and activation of THP-1 macrophages. Life Sci. 2002;71:2499–508.

Pérez-Rodríguez R, Roncero C, Oliván AM, González MP, Oset-Gasque MJ. Signaling mechanisms of interferon gamma induced apoptosis in chromaffin cells: involvement of nNOS, iNOS, and NFκB. J Neurochem. 2009;108:1083–96.

Selleri C, Maciejewski JP, Sato T, Young NS. Interferon-gamma constitutively expressed in the stromal microenvironment of human marrow cultures mediates potent hematopoietic inhibition. Blood. 1996;87:4149–57.

Zeng W, Miyazato A, Chen G, Kajigaya S, Young NS, Maciejewski JP. Interferon-γ-induced gene expression in CD34 cells: identification of pathologic cytokine-specific signature profiles. Blood. 2006;107:167–75.

Walter D, Lier A, Geiselhart A, Thalheimer FB, Huntscha S, Sobotta MC, et al. Exit from dormancy provokes DNA-damage-induced attrition in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2015;520:549–52.

Gao Y, Grassi F, Ryan MR, Terauchi M, Page K, Yang X, et al. IFN-γ stimulates osteoclast formation and bone loss in vivo via antigen-driven T cell activation. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:122–32.

Kamperschroer C, Quinn DG. The role of proinflammatory cytokines in wasting disease during lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. J Immunol. 2002;169:340–9.

Masters SL, Gerlic M, Metcalf D, Preston S, Pellegrini M, O’Donnell JA, et al. NLRP1 inflammasome activation induces pyroptosis of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Immunity. 2012;37:1009–23.

Lulli V, Romania P, Riccioni R, Boe A, Lo-Coco F, Testa U, et al. Transcriptional silencing of the ETS1 oncogene contributes to human granulocytic differentiation. Haematologica. 2010;95:1633–41.

Moriguchi T, Yamamoto M. A regulatory network governing Gata1 and Gata2 gene transcription orchestrates erythroid lineage differentiation. Int J Hematol. 2014;100:417–24.

Libregts SF, Gutiérrez L, de Bruin AM, Wensveen FM, Papadopoulos P, Van IW, et al. Chronic IFN-γ production in mice induces anemia by reducing erythrocyte life span and inhibiting erythropoiesis through an IRF-1/PU. 1 axis. Blood. 2011;118:2578–88.

de Bruin AM, Libregts SF, Valkhof M, Boon L, Touw IP, Nolte MA. IFNγ induces monopoiesis and inhibits neutrophil development during inflammation. Blood. 2012;119:1543–54.

Mossadegh-Keller N, Sarrazin S, Kandalla PK, Espinosa L, Stanley ER, Nutt SL, et al. M-CSF instructs myeloid lineage fate in single haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2013;497:239–43.

Hirai H, Zhang P, Dayaram T, Hetherington CJ, Mizuno S, Imanishi J, et al. C/EBPβ is required for “emergency” granulopoiesis. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:732–9.

•• Kaufmann E, Sanz J, Dunn JL, et al. BCG educates hematopoietic stem cells to generate protective innate immunity against tuberculosis. Cell. 2018;172:176–182.e19. Shows how HSCs undergo genetic and epigenetic reprograming after immune challenge.

Krebs DL, Hilton DJ. SOCS proteins: negative regulators of cytokine signaling. Stem Cells. 2001;19:378–87.

Yoshihara H, Arai F, Hosokawa K, Hagiwara T, Takubo K, Nakamura Y, et al. Thrombopoietin/MPL signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and interaction with the osteoblastic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:685–97.

Kato Y, Iwama A, Tadokoro Y, Shimoda K, Minoguchi M, Akira S, et al. Selective activation of STAT5 unveils its role in stem cell self-renewal in normal and leukemic hematopoiesis. J Exp Med. 2005;202:169–79.

Warr MR, Binnewies M, Flach J, Reynaud D, Garg T, Malhotra R, et al. FOXO3A directs a protective autophagy program in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2013;494:323–7.

King KY, Baldridge MT, Weksberg DC, Chambers SM, Lukov GL, Wu S, et al. Irgm1 protects hematopoietic stem cells by negative regulation of interferon signaling. Blood. 2011;118:1525–33.

Ehninger A, Trumpp A. The bone marrow stem cell niche grows up: mesenchymal stem cells and macrophages move in. J Exp Med. 2011;208:421–8.

Nagasawa T, Omatsu Y, Sugiyama T. Control of hematopoietic stem cells by the bone marrow stromal niche: the role of reticular cells. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:315–20.

Morrison SJ, Spradling AC. Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell. 2008;132:598–611.

Morrison SJ, Scadden DT. The bone marrow niche for haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2014;505:327–34.

Umemoto T, Yamato M, Shiratsuchi Y, Terasawa M, Yang J, Nishida K, et al. Expression of integrin β3 is correlated to the properties of quiescent hemopoietic stem cells possessing the side population phenotype. J Immunol. 2006;177:7733–9.

Umemoto T, Yamato M, Ishihara J, Shiratsuchi Y, Utsumi M, Morita Y, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells integrin-avb3 regulates thrombopoietin-mediated maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2012;119:83–94.

Ishihara J, Umemoto T, Yamato M, Shiratsuchi Y, Takaki S, Petrich BG, et al. Nov/CCN3 regulates long-term repopulating activity of murine hematopoietic stem cells via integrin αvβ3. Int J Hematol. 2014;99:393–406.

Wang L, Liu S, Zhao Y, Liu D, Liu Y, Chen C, et al. Osteoblast-induced osteoclast apoptosis by FAS ligand/FAS pathway is required for maintenance of bone mass. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:1654–64.

Calvi L, Adams G, Weibrecht K, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:841–6.

Azuma Y, Kaji K, Katogi R, Takeshita S, Kudo A. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces differentiation of and bone resorption by osteoclasts. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4858–64.

Jia H, Thelwell C, Dilger P, Bird C, Daniels S, Wadhwa M. Endothelial cell functions impaired by interferon in vitro: insights into the molecular mechanism of thrombotic microangiopathy associated with interferon therapy. Thromb Res. 2018;163:105–16.

Eltoukhy HS, Sinha G, Moore C, Guiro K, Rameshwar P. CXCL12-abundant reticular cells (CAR) cells: a review of the literature with relevance to cancer stem cell survival. J Cancer Stem Cell Res. 2016;4:1–7.

Chou DB, Sworder B, Bouladoux N, Roy CN, Uchida AM, Grigg M, et al. Stromal-derived IL-6 alters the balance of myeloerythroid progenitors during Toxoplasma gondii infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:123–31.

Zhao M, Perry JM, Marshall H, Venkatraman A, Qian P, He XC, et al. Megakaryocytes maintain homeostatic quiescence and promote post-injury regeneration of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2014;20:1321–6.

Bruns I, Lucas D, Pinho S, Ahmed J, Lambert MP, Kunisaki Y, et al. Megakaryocytes regulate hematopoietic stem cell quiescence through CXCL4 secretion. Nat Med. 2014;20:1315–20.

•• Chen X, Deng H, Churchill MJ, Luchsinger LL, du X, Chu TH, et al. Bone marrow myeloid cells regulate myeloid-biased hematopoietic stem cells via a histamine-dependent feedback loop. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:747–760.e7. Provides evidence of myeloid-derived histamine as a regulator of HSC quiescence.

Dufour C, Capasso M, Svahn J, Marrone A, Haupt R, Bacigalupo A, et al. Homozygosis for (12) CA repeats in the first intron of the human IFN-γ gene is significantly associated with the risk of aplastic anaemia in Caucasian population. Br J Haematol. 2004;126:682–5.

Pietras EM, Mirantes-Barbeito C, Fong S, Loeffler D, Kovtonyuk LV, Zhang SY, et al. Chronic interleukin-1 exposure drives haematopoietic stem cells towards precocious myeloid differentiation at the expense of self-renewal. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:607–18.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Catherine Gillespie for critical reading and editing of this manuscript. This work was supported by the Aplastic Anemia and MDS International Foundation Liviya Anderson Award (KYK), a March of Dimes Basil O’Connor Starter Scholar Award (KYK), and the National Institutes of Health: NIH5T32HL092332 (DEMM), NIH5R25GM056929 (DEMM), R01HL136333 (KYK), and R01HL134880 (KYK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Daniel E. Morales-Mantilla and Katherine Y. King declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All reported studies/experiments with human or animal subjects performed by the authors have been previously published and complied with all applicable ethical standards (including the Helsinki declaration and its amendments, institutional/national research committee standards, and international/national/institutional guidelines).

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Role of Classical Signaling Pathways in Stem Cell Maintenance

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Morales-Mantilla, D.E., King, K.Y. The Role of Interferon-Gamma in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Development, Homeostasis, and Disease. Curr Stem Cell Rep 4, 264–271 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40778-018-0139-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40778-018-0139-3