Abstract

Introduction

European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI) is a clinician-reported outcome (ClinRO) instrument, assessing Sjögren’s disease activity from the physician perspective. EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient Reported Index (ESSPRI) is a patient-reported outcome (PRO) instrument, assessing patient-defined Sjögren’s symptom severity. Both instruments are commonly used as clinical trial endpoints and have been psychometrically validated. However, qualitative evidence supporting content validity and what constitutes a meaningful change is limited. Qualitative evidence supporting Physician/Patient Global Assessment of disease activity and symptom severity (PhGA/PaGA) items used within anchor-based analyses for ESSDAI/ESSPRI is also lacking.

Methods

Qualitative, semi-structured, telephone/video interviews were conducted with patients with Sjögren’s (n = 12) and physicians who specialise in Sjögren’s (n = 10). Interviews explored: appropriateness of ESSDAI domain weights and meaningful improvements on domain/total scores from the physician perspective, appropriateness of ESSPRI’s 2-week recall period from the patient/physician perspective, patients’ perspectives on meaningful improvements in ESSPRI total scores, and patients’/physicians’ interpretation of PhGA/PaGA items.

Results

Most ESSDAI domain weights were considered clinically appropriate. Generally, a one-category improvement in domain-level scores and a 3-point improvement in total ESSDAI scores were considered clinically meaningful. Most patients/physicians considered ESSPRI’s 2-week recall period appropriate, and patients considered a 1-to-2-point ESSPRI total score improvement meaningful. PhGA/PaGA items developed for use as ESSDAI/ESSPRI anchors were consistently interpreted.

Conclusions

The findings support use of ESSDAI and ESSPRI as Sjögren’s clinical trials endpoints, as well as in clinical practice and other research settings. Qualitative data exploring meaningful change supports existing minimal clinically important improvement (MCII) thresholds.

Plain Language Summary

European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI) is an assessment used by physicians to measure how active Sjögren’s is in individuals with the condition. EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient Reported Index (ESSPRI) is a questionnaire completed by individuals with Sjögren’s to assess the severity of their symptoms. It is important to show that ESSDAI and ESSPRI are considered appropriate by physicians and individuals with Sjögren’s, respectively, and that ESSPRI is well understood by individuals with Sjögren’s completing the questionnaire. Therefore, interviews were conducted with physicians who specialise in Sjögren’s to explore the appropriateness of ESSDAI, the level of improvement on the assessment that would be important to individuals with Sjögren’s, and the appropriateness of the ESSPRI recall period (i.e. whether it is acceptable to ask individuals to remember their symptoms over the past 2 weeks). Interviews were also conducted with individuals with Sjögren’s to explore their understanding and relevance of ESSPRI (including the 2-week recall period) and the level of improvement on the questionnaire that would be important to them. Most physicians and patients considered ESSDAI and ESSPRI appropriate, supporting their use in a range of settings including Sjögren’s clinical trials, clinical practice and other research settings. Most physicians reported that a 3-point improvement in ESSDAI total score would be meaningful to individuals with Sjögren’s. Individuals with Sjögren’s reported that a 1-to-2-point improvement in ESSPRI total score would be meaningful.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Sjögren’s disease activity can be assessed from the physician perspective using European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) Sjögren's Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI), and patient-defined Sjögren’s symptom severity can be assessed using EULAR Sjögren's Syndrome Patient Reported Index (ESSPRI) |

Although both instruments are commonly used as clinical trial endpoints and have been psychometrically validated, evidence supporting content validity and what constitutes a meaningful change is limited |

This study investigated the appropriateness of ESSDAI and ESSPRI, as well as meaningful improvements on ESSDAI from the physician perspective and ESSPRI from the patient perspective |

What was learned from the study? |

Most physicians and patients considered ESSDAI and ESSPRI appropriate, with most physicians reporting a 3-point improvement in ESSDAI total score as meaningful, and most patients reporting a 1-to-2-point improvement in ESSPRI total score as meaningful |

The findings support the use of ESSDAI and ESSPRI as Sjögren’s clinical trial endpoints, in clinical practice and in other research settings, and qualitative data exploring meaningful change support existing minimal clinically important improvement (MCII) thresholds |

Introduction

Sjögren’s is a chronic autoimmune disease of unknown aetiology, characterised by lymphoid infiltration and progressive destruction of exocrine glands [1]. Approximately 30–40% of patients have potentially serious systemic organ involvement that can greatly affect morbidity and mortality [2,3,4,5]. Cardinal symptoms include eyes, mouth, skin and female genitalia dryness; however, the inflammatory process can target any organ [6, 7]. As such, Sjögren’s is heterogeneous and characterised by a combination of clinical features and subjective symptoms best assessed using clinical tests and patient reports, respectively [8, 9]. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI) [10] and the EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient Reported Index (ESSPRI) [11] were developed for this purpose and are increasingly being used within clinical practice [11,12,13] and as clinical trial endpoints to evaluate treatment benefit [9, 14,15,16,17,18].

ESSDAI is a 12-domain clinician-reported outcome (ClinRO) instrument assessing systemic disease activity, developed with the involvement of physicians who specialise in Sjögren’s [10]. For each domain, clinicians rate patients’ disease activity using pre-defined descriptions. ESSDAI domains are weighted to reflect their contribution to total disease activity. Multiple regression modelling was used to determine domain weights (ranging from one to six), according to the strength of each domain’s relationship with a Physician Global Assessment (PhGA) of disease activity item [10]. Domain scores are obtained by multiplying the level of activity by the domain weight, and the 12 domain scores are combined to obtain the ESSDAI total score, ranging from 0 to 123. Low, moderate and high disease activity is defined by scores of < 5, 5–13 and ≥ 14, respectively. A minimal clinically important improvement (MCII) of ≥ 3 points has also been defined using anchor-based analysis [16, 19].

ESSPRI is a 3-item patient-reported outcome (PRO) instrument assessing the severity of dryness, fatigue and joint/muscle pain over the past 2 weeks [11]. Items were selected on the basis of qualitative interview data regarding the importance of Sjögren’s symptoms obtained during development of the Sicca Symptoms Inventory [20] and Profile of Fatigue and Discomfort (PROFAD) [12] and were confirmed using multiple regression modelling. Items are rated on a 0–10 numerical rating scale (NRS), and a mean total score is calculated where higher scores indicate worse symptom severity. Quantitative research suggests that patients consider their symptom severity acceptable when their ESSPRI total score is ≤ 5 (Patient Acceptable Symptom Score; PASS), with an MCII of ≥ 1 point or 15% score reduction [19].

Quantitative evidence to support the reliability and validity of both ESSDAI [4, 19, 21,22,23] and ESSPRI [14, 19, 21, 24] is well documented. However, there is limited qualitative evidence to support content validity of these instruments, specifically the appropriateness of ESSDAI’s domain weights and scoring approach, and ESSPRI’s 2-week recall period. Regulators such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognise the critical role that patients and physicians play in developing Clinical Outcome Assessment (COA) instruments for use as clinical trial endpoints, and increasingly seek qualitative evidence to support their content validity [25,26,27,28,29,30]. Furthermore, there is a lack of qualitative evidence in Sjögren’s to support and contextualise meaningful change thresholds generated using anchor-based analysis, as recommended by the FDA [28, 29].

PhGA of disease activity and Patient Global Assessment (PaGA) of symptom severity items using a 0–10 NRS are commonly used to support anchor-based analyses relating to ESSDAI/ESSPRI [14, 31,32,33]. Anchor-based analyses are central to assessing meaningful within-patient change on COA instruments by exploring the relationship between the concept of interest and an external anchor. Existing PhGA/PaGA items using a 0–10 NRS do not meet FDA criteria for anchors, so new PhGA/PaGA items were developed and evaluated in this study [27, 28, 34, 35].

Methods

Sample and Recruitment

Two cross-sectional, non-interventional, qualitative interview studies involving patients with Sjögren’s and physicians who specialise in Sjögren’s were conducted. Patients from diverse locations in the USA (Baltimore, Maryland; Chicago, Illinois; Los Angeles, California; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and St Louis, Missouri) were recruited via MedQuest Global Market Research using physician referrals. Sampling quotas relating to key demographic and clinical characteristics were employed to ensure insights were obtained from a diverse sample of patients who were representative of the wider Sjögren’s population, in line with best practice guidelines for collecting comprehensive and representative input (Table 2) [30].

Physicians who specialise in Sjögren’s from the USA, the UK and Germany were approached by the sponsor to participate in an interview. As most physicians involved in the original development of ESSDAI and ESSPRI were European, meaning their perspectives were well incorporated [10, 11, 19], a sampling quota was employed to ensure greater representation of US physicians in this study to provide additional clinical perspectives from this region. Similarly, ESSPRI items were developed on the basis of qualitative interview data obtained from patients from the UK during development of the Sicca Symptoms Inventory and PROFAD. Therefore, the inclusion of US patients in this study provides an additional patient perspective and supplements the previous research. Patients and physicians were required to meet pre-defined eligibility criteria (Table 1).

Although no minimum sample size is required for interview studies, it is acknowledged that Sjögren’s can be highly heterogeneous, meaning a relatively large number of patients would be required to fully explore the disease experience. However, the focus of this study was to debrief ESSDAI and ESSPRI using cognitive interview methods, and research suggests that seven to ten participants are sufficient to comprehensively assess the content validity of COA instruments [36]. Further, as both ESSDAI and ESSPRI are well established, and quantitative evidence to support the reliability and validity of both instruments is well documented, the aim of this study was to generate additional, supportive qualitative evidence to fill specific evidence gaps. Therefore, the patient (n = 12) and physician (n = 10) samples were considered adequate.

Qualitative Interviews

Interviews were conducted by trained Adelphi Values interviewers via telephone or Microsoft Teams video call, between March and June 2021. Semi-structured interview guides were used to facilitate patient (approximately 90 min) and physician (approximately 60 min) interviews. Interviews were designed and conducted in line with best practice guidance for qualitative research, such as ensuring questions were framed in an unbiased manner by using open-ended and non-leading questions [28].

For ESSDAI, the purpose was to obtain physician feedback on (i) the appropriateness of the 12 organ-specific domain weights (constitutional, lymphadenopathy & lymphoma (L&L), glandular, articular, cutaneous, pulmonary, renal, muscular, peripheral nervous system (PNS), central nervous system (CNS), haematological and biological), (ii) the level of change that would be clinically meaningful at the individual domain (e.g. a one-category improvement from moderate to low) and total score level (e.g. what decrease would suggest a clinically meaningful improvement) and (iii) the best approach to calculating a total score.

For ESSPRI, the objectives were to (i) explore the appropriateness and feasibility of the 2-week recall period from the patient and physician perspective, and (ii) explore patients’ perspectives on item relevance and the level of change they would consider meaningful at the total score level.

The existing (0–10 NRS) and newly developed (4-point Likert scale) versions of the PhGA and PaGA items were also debriefed to explore physician and patient interpretation (Fig. 1). The FDA Patient Focused Drug Development (PFDD) guidance series (including example items) [28, 29] was used to design the Likert versions of the PhGA and PaGA. Specifically, the items were developed to match the concepts assessed by ESSDAI (overall disease activity) and ESSPRI (severity of symptoms), with distinct, non-overlapping response categories, and recall periods equivalent to ESSDAI (today) and ESSPRI (past 2 weeks) [27, 28, 34, 35].

Versions of the PhGA and PaGA items tested. *Please note that two additional versions of the Likert scale PaGA item using recall periods of ‘today’ and ‘the past week’ were also tested but are not discussed in this paper as they do not relate to ESSPRI. PhGA Physician’s Global Assessment, PaGA Patient’s Global Assessment, NRS numerical rating scale

Qualitative Analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Qualitative analysis was conducted using ATLAS.Ti software [37] and framework and thematic analysis methods [36, 38, 39]. An induction–abduction approach was taken to identify themes emerging directly from the data (inductive inference), and by applying prior knowledge (abductive inference). Separate coding schemes were derived for both sets of interviews and used throughout the analysis process to ensure consistent application and grouping of codes by trained and experienced researchers.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval and oversight was provided by Salus Independent Review Board (IRB), a centralised IRB in the USA (physician protocol ID: NO9051A; patient protocol ID: NO9052A). All participants provided oral and written informed consent prior to the conduct of any research activities. Both studies were designed and conducted in accordance with best practice guidelines [40, 41] and the ethical principles laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments [42].

Results

Patient Characteristics

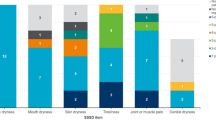

A total of 12 patients were interviewed. All demographic and clinical sampling quotas implemented to promote heterogeneity and representation of the Sjögren’s population (Table 2) were met or exceeded except for the education level category ‘completed high school or below only’ (≥ 3 target; 2 actual). Patients were mostly female (n = 8/12; 67%) with a mean age of 56.1 years (range 20–80 years). Although Sjögren’s is more common in white individuals (hence the racial quota relating to white and non-white) [43], white and non-white individuals were equally represented (n = 6/12; 50%, each) (Table 2). Most patients (n = 10/12; 83%) had received a Sjögren’s diagnosis within the last 10 years and were predominately classified as having moderate (n = 5/12; 42%) or high (n = 4/12; 33%) disease activity on the basis of PhGA score. At screening, most patients (n = 9/12; 75%) had an unsatisfactory symptom state (≥ 5 ESSPRI score) and experiences of eye dryness (n = 12/12; 100%), tiredness/fatigue (n = 11/12; 92%) and mouth dryness (n = 8/12; 67%), among other symptoms.

Physician Characteristics

A total of ten physicians, all rheumatologists, were interviewed and met all sampling quotas. Five (n = 5/10; 50%) physicians were female, and were predominantly from the USA (n = 8/10; 80%). All physicians had been qualified for at least 10 years, treating patients for at least 5 years and treating patients with Sjögren’s on a weekly (n = 9/10; 90%) or monthly (n = 1/10; 10%) basis at the time of interview. On average, physicians treated at least 20 patients with Sjögren’s per month and worked in a range of settings, including academia (n = 8/10; 80%), private practice (n = 3/10; 30%) and/or hospital-based care (n = 2/10; 20%). Physicians reported using ESSDAI (n = 7/10; 70%) and ESSPRI (n = 4/9; 44%) to assess Sjögren’s disease activity in their clinical practice.

ESSDAI

Appropriateness of Domain Weights

Most domain weights were considered clinically appropriate by most (≥ 50%) physicians (Fig. 2). However, the glandular (domain weight of 2), articular [2] and biological [1] domains were considered slightly underweighted and the muscular [6] domain was considered slightly overweighted by ≥ 50% of physicians. Physicians who considered the glandular (n = 5/10; 50%), articular (n = 6/10; 60%) and/or biological (n = 6/10; 60%) domains slightly underweighted commented on the domains representing an important/prevalent aspect of disease activity, being significantly impactful to patients’ feelings and functioning, and/or being relevant to assess in the context of a clinical trial. However, physicians suggested that these domain weights were only ‘a little low’, and recommendations for increased weights tended to only be 1–2 points higher. Physicians who suggested that the muscular domain was slightly overweighted (n = 7/10; 70%) stated that muscular involvement due to Sjögren’s is rare and/or not as severe as other organ involvement. Additionally, physicians reported that it can be difficult to separate muscular involvement due to Sjögren’s from other comorbid conditions and weakness due to steroids. Again, the weight was only considered ‘a little high’, and despite these suggestions of increasing/decreasing domain weights, no physicians suggested that ESSDAI was inappropriate for use in its current format.

Meaningful Improvement

All physicians asked reported that a one-category improvement (e.g. moderate to low activity level) would be clinically meaningful for the constitutional (n = 10/10; 100%), pulmonary (n = 10/10; 100%), renal (n = 8/8; 100%) and biological domains (n = 8/8; 100%). For the remaining domains, a minority of physicians reported that a two-category improvement (e.g. moderate to no activity level) would be clinically meaningful (≤ 30%). Reasons for a two-category improvement included the domain typically being responsive to treatment (glandular, articular, cutaneous, muscular), there being natural fluctuation in the domain (glandular, articular), variation/subjectivity in how the disease activity levels are interpreted by physicians (cutaneous, PNS), and requiring a change substantial enough to make the patient feel better (CNS, haematological). For seven domains, all or most physicians (≥ 80%) reported that patients would also consider the same level of improvement meaningful (one or two categories). For the L&L, muscular and haematological domains, a few physicians (≤ 30%) reported that the change may not be meaningful to patients, and some physicians (≤ 40%) reported that patients were unlikely to notice changes in the renal and biological domains, as these changes would be more evident in objective tests of disease activity (e.g. complement and Immunoglobulin G (IGG) levels) as opposed to patients’ feeling and functioning.

The existing MCII threshold of 3 points on the ESSDAI total score [16, 19] was most frequently reported as clinically meaningful by physicians (n = 5/10; 50%). However, notable caveats included meaningfulness being dependent upon the domains that have changed (n = 1/2; 50%), and patients’ baseline ESSDAI score (n = 1/2; 50%).

Best Approach to Calculating an ESSDAI Score

Owing to interview time constraints, only four physicians (n = 4/10; 40%) discussed the best approaches to calculating and tracking ESSDAI total scores. Four approaches were recommended: the validated approach of summing weighted domain scores to calculate a total score (n = 2/4; 50%) [10, 19, 21], tracking individual domain scores (n = 2/4; 50%), calculating separate total scores for domains in which disease activity is reversible versus irreversible (n = 1/4; 25%), and generating a total score without domain weights (n = 1/4; 25%). The two physicians (n = 2/4; 50%) who recommended tracking individual domain scores did so to avoid changes within domains being diluted within a total score (n = 1/2; 50%) and to separately track domains in which disease activity is reversible or irreversible (n = 1/2; 50%). To note, this was a misconception, domains should not be scored when damage is present. The physician that suggested calculating an ESSDAI score without domain weights only did so to reduce the complexity of the calculation (n = 1/4; 25%).

ESSPRI

Relevance and Interpretation of ESSPRI Items

ESSPRI items were considered relevant to most patients within the 2-week recall period: dryness (n = 12/12; 100%), fatigue (n = 10/12; 83%) and pain (n = 11/12; 92%). However, there was variation in interpretation of the dryness item, with most patients considering more than one area [eye dryness (n = 9/11; 82%), mouth dryness (n = 4/11; 36%) and skin dryness (n = 3/11; 27%)] and tending to focus on the most severe areas of dryness.

Recall Period

The 2-week recall period was considered appropriate to assess average symptom severity by most physicians (n = 7/10; 70%). Reasons for this included the recall period accounting for day-to-day variability of symptoms (n = 2/7; 23%) and patients with Sjögren’s being ‘focused’ on their symptoms allowing for reliable self-reports (n = 2/7; 23%). However, two physicians (n = 2/10; 20%) suggested that patients may think only about their worst symptoms, and one physician (n = 1/10; 10%) felt the recall period is too long relative to shorter recall periods used in other rheumatologic diseases and may diminish treatment efficacy. A subset of physicians (n = 5/6; 83%) considered the 2-week recall period to be clinically meaningful. Only one physician provided a rationale, explaining that, as Sjögren’s symptoms fluctuate day to day, having a general trend is more clinically meaningful when considering treatment choices.

Almost all patients (n = 11/12; 92%) reported that it would be easy to remember symptom severity over the past 2 weeks. Most patients demonstrated an understanding of the 2-week recall period (≥ 92%) and considered the recall period appropriate (≥ 83%) across individual items.

Meaningful Change

Most patients reported that a 2-point (n = 5/12; 42%) or 1-point (n = 3/12; 25%) (range 1–6) improvement in their total ESSPRI score would be meaningful, and that a 2-point improvement (n = 5/11; 45%) would justify using a new treatment (range 1–4). Patients reported that a 1-to-2-point improvement would reduce symptom severity (n = 1/5; 20%), frequency (n = 1/5; 20%) and bothersomeness (n = 1/5; 20%), reduce impact to activities of daily living (n = 1/5; 20%) and improve emotional wellbeing (n = 1/5; 20%). Similarly, most patients felt a 1-point (n = 4/12; 33%) or 2-point (n = 6/12; 50%) worsening in their total ESSPRI score would be meaningful. Table 3 provides patient quotes reflecting how ESSPRI total score improvements would affect how they feel and function.

PhGA

Both PhGA items were well understood by physicians, the majority (≥ 80%) considering both systemic and glandular disease activity when responding to both items. However, the Likert version was interpreted more consistently as referring specifically to disease activity than the 0–10 NRS version, for which physicians reported that they would consider a range of concepts in addition to disease activity, including symptoms (n = 9/10; 90%), impacts (n = 4/10; 40%) and global health status (n = 3/10; 30%). Physicians frequently reported that they would require objective laboratory test results (e.g. blood work, inflammatory markers or complement antibodies levels; ≥ 71%), conduct physical examinations (≥ 56%) and/or collect patient-reported information (≥ 43%) before answering each version.

PaGA

Although both PaGA items were well understood, the Likert version was interpreted more consistently as an assessment of overall symptom severity with most patients considering all their symptoms when responding (n = 11/12; 92%). The 0–10 NRS version varied in interpretation, with fewer patients considering all their symptoms (n = 5/12; 42%) and some considering the effects/impacts of Sjögren’s (n = 2/12; 17%) and/or specific symptoms only [eye dryness (n = 4/12; 33%), mouth dryness (n = 1/12; 8%) and pain (n = 1/12; 8%)]. Patient and physician preferences for different response scales, including the 0–10 NRS and Likert scale used in the PaGA/PhGA items, were also explored during interviews, and the findings are published elsewhere [44].

Discussion

Although quantitative evidence to support the reliability and validity of both ESSDAI [4, 19, 21,22,23] and ESSPRI [14, 19, 21, 24] is well documented, to our knowledge, this paper is the first to present qualitative data supporting the content validity and exploring meaningful change on ESSDAI and ESSPRI, and the content validity of corresponding PhGA/PaGA anchors. In doing so, the data address a key evidence gap and support use of ESSDAI and ESSPRI in their current formats as clinical trial endpoints, as well as their use in routine clinical practice and other research settings.

The data support the majority of ESSDAI domain weights in their current format, aligning with and providing supplementary evidence to the opinions of 44 experts from 15 countries who confirmed during development of ESSDAI that the domain weights generated using regression modelling were appropriate from a clinical perspective [10]. Where physicians suggested a small number of domains were slightly underweighted/overweighted, their reasoning did not always consider the aim of ESSDAI domain weights. For example, some physicians considered the articular, biological and glandular domains to be slightly underweighted, suggesting they represent prevalent aspects of Sjogren’s that are impactful to patients’ feelings and functioning. While it is interesting to note that these domains may have a more direct impact on patient-reported symptoms and impacts, ESSDAI is ultimately a clinical assessment of overall disease activity. As such, during ESSDAI development EULAR agreed that domain weights should reflect the type and severity of involvement, irrespective of their frequency, particularly as potentially lethal organ manifestations are likely to have a greater impact on morbidity and prognosis [10]. Further, physicians stated that domain weights were only ‘a little’ low, and none reported that ESSDAI was inappropriate in its current format. In line with the FDA’s PFDD guidance and the greater emphasis on the use of qualitative data to support and contextualise meaningful change thresholds [28, 29], this study also generated qualitative insights that supports and complements the existing MCII threshold of ≥ 3 points on ESSDAI, generated using anchor-based analysis [19]. The findings therefore support the use of this responder definition in clinical trial endpoints.

Regarding ESSPRI, the 2-week recall period was considered both appropriate and feasible by patients, and clinically relevant by expert physicians. Although variability in interpretation of the dryness item was observed, multiple regression modelling during ESSPRI development found that the individual PROFAD dryness items were highly correlated, suggesting conceptual redundancy. Therefore, EULAR deemed it appropriate to use a generic dryness item [11]. Again, in line with the FDA’s PFDD guidance and the greater emphasis on the use of qualitative data to support and contextualise meaningful change thresholds [28, 29], this study found that most patients considered a 1-to-2-point improvement meaningful. Importantly, these qualitative insights support the recently published MCII threshold of ≥ 1.5 points generated using anchor- and distribution-based analyses [19, 45]. Although patients frequently reported a slightly greater improvement of 2 points as meaningful, a 1-point improvement was the next most frequent response, and qualitative meaningful change data should only be used to support and contextualise responder definitions generated using psychometric analyses [29]. Further, research suggests that satisfaction with total score improvements in Sjögren’s can depend on which symptoms improve, owing in part to the heterogeneity of the condition [46]. This was not assessed in relation to ESSPRI as part of the present study but would be interesting to explore in future research.

The data also demonstrate that the newly developed Likert versions of the PhGA/PaGA items were well understood and consistently interpreted by physicians and patients. In line with regulatory guidance, this supports the content validity of these items and their use as anchors for total disease activity (ESSDAI) and symptom severity (ESSPRI) when administration matches trial endpoints [27,28,29]. The findings also support use of these items in routine clinical practice and other research settings to assess disease activity and symptom severity from the physician and patient perspective, respectively. Notably, physicians frequently reported that they would rely on physical examinations, patient-reported information and objective laboratory tests to complete the PhGA. These findings provide useful insights for clinical trial designs, suggesting there would be value in physicians completing the PhGA following ESSDAI to ensure physicians have access to all relevant information and test results to inform responses and decision-making.

Limitations

It could be argued that male and non-white individuals were overrepresented in the sample as Sjögren’s has a strong female and white predominance [4, 43, 47]. However, the aim was to sufficiently represent white females while promoting heterogeneity in the sample so that understanding/relevance of items could be assessed across patients with varying characteristics. It could also be suggested that the sample sizes were relatively small, therefore limiting the generalisability of the findings, particularly given the fluctuation and heterogeneity of Sjögren’s symptoms, meaning a relatively large number of patients would be required to fully explore the disease experience. However, the aim of this study was to debrief ESSDAI and ESSPRI using cognitive interview methods, and research suggests that seven to ten participants are adequate to comprehensively assess the content validity of COA instruments [36]. Further, given that a number of experts were involved in the development and validation of ESSDAI, and that ESSPRI development was driven by patient-reported data, the samples were deemed appropriate to supplement this evidence and gain additional insights on specific areas of interest in Sjögren’s.

Physicians were recruited by the study sponsor via convenience sampling, which may have introduced sponsorship bias that would not have existed had an external sample of physicians been recruited. However, interviews were conducted by a research agency, and physicians were reminded of their right to confidentiality and anonymity and were encouraged to share their honest opinions. Further, the sample was diverse in terms of other sociodemographic characteristics and clinical experience, providing variability in experiences/perspectives. The physician sample was also composed of mostly US physicians, which provided clinical perspectives from a different region, given that European physicians’ perspectives were well incorporated during the development of ESSDAI and ESSPRI. Similarly, qualitative interview data obtained from UK patients during the development of the Sicca Symptoms Inventory and PROFAD was used to develop the ESSPRI items. Therefore, the inclusion of US patients in this study provides an additional patient perspective and supplements the previous research. Nevertheless, future research could be conducted using translated versions of ESSDAI and ESSPRI to confirm their content validity in physicians and patients with Sjögren’s from different countries.

Finally, owing to time constraints, it was not possible to obtain feedback from all participants on all aspects of ESSDAI and ESSPRI. However, both instruments are well established [9, 14, 16], and quantitative evidence to support the reliability and validity of both ESSDAI [4, 19, 21,22,23] and ESSPRI [14, 19, 21, 24] is well documented. As such, the focus of this study was to generate additional qualitative evidence relating to specific evidence gaps. Future research should explore topics of interest not included in the present study. For instance, although patients and physicians considered ESSPRI’s recall period appropriate and feasible, a separate validation study would be beneficial to test the reliability of patients’ responses.

Conclusion

The present study supports and complements existing evidence regarding the use of ESSDAI and ESSPRI in their current format as instruments that are complementary to each other; the majority considered the current ESSDAI domain weights appropriate for assessment of Sjögren’s disease activity, and the ESSPRI 2-week recall period is appropriate and feasible. These data therefore ultimately support use of the instruments in the context of clinical trial endpoints, routine clinical practice and other research settings. The data also support the content validity of the new PhGA and PaGA items (with Likert response scales) as anchors for ESSDAI and ESSPRI, as well as providing recommendations for their administration within Sjögren’s clinical trials. Patient- and physician-reported thresholds for meaningful improvements on the COA instruments are valuable in interpreting statistically derived responder definitions for clinical trial endpoints, and perspectives on ESSDAI scoring will be valuable in supporting psychometric exploration of scoring approaches for this instrument. Taken together, the qualitative findings address key evidence gaps and provide valuable insights informing use of ESSDAI and ESSPRI as clinical trial endpoints, use of PhGA and PaGA items in anchor-based analyses, and the interpretation of responder definitions.

References

Seror R, Gottenberg J, Devauchelle-Pensec V, et al. European League Against Rheumatism Sjögren's Syndrome Disease Activity Index and European League Against Rheumatism Sjögren's Syndrome Patient-Reported index: a complete picture of primary Sjögren's syndrome patients. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65(8):1358–64.

Mariette X, Criswell LA. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(10):931–9.

Nocturne G, Mariette X. Sjögren syndrome-associated lymphomas: an update on pathogenesis and management. Br J Haematol. 2015;168(3):317–27.

Brito-Zerón P, Kostov B, Solans R, et al. Systemic activity and mortality in primary Sjögren syndrome: predicting survival using the EULAR-SS Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI) in 1045 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(2):348–55.

Ramos-Casals M, Tzioufas AG, Font J. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome: new clinical and therapeutic concepts. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(3):347–54.

Asmussen K, Andersen V, Bendixen G, Schiodt M, Oxholm P. A new model for classification of disease manifestations in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: evaluation in a retrospective long-term study. J Intern Med. 1996;239(6):475–82.

Palm Ø, Garen T, Berge Enger T, et al. Clinical pulmonary involvement in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: prevalence, quality of life and mortality—a retrospective study based on registry data. J Rheumatol. 2013;52(1):173–9.

Stefanski A-L, Tomiak C, Pleyer U, Dietrich T, Burmester GR, Dörner T. The diagnosis and treatment of Sjögren’s syndrome. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(20):354–61.

Tarn JR, Howard-Tripp N, Lendrem DW, et al. Symptom-based stratification of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: multi-dimensional characterisation of international observational cohorts and reanalyses of randomised clinical trials. Lancet Rheumatol. 2019;1(2):e85–94.

Seror R, Ravaud P, Bowman SJ, et al. EULAR Sjögren’s syndrome disease activity index: development of a consensus systemic disease activity index for primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):1103–9.

Seror R, Ravaud P, Mariette X, et al. EULAR Sjogren’s syndrome patient reported index (ESSPRI): development of a consensus patient index for primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):968–72.

Bowman SJ, Booth DA, Platts RG. Measurement of fatigue and discomfort in primary Sjogren’s syndrome using a new questionnaire tool. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43(6):758–64.

Cho HJ, Yoo JJ, Yun CY, et al. The EULAR Sjögren’s syndrome patient reported index as an independent determinant of health-related quality of life in primary Sjögren’s syndrome patients: in comparison with non-Sjögren’s sicca patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52(12):2208–17.

Cornec D, Devauchelle-Pensec V, Mariette X, et al. Severe health-related quality of life impairment in active primary Sjögren’s syndrome and patient-reported outcomes: data from a large therapeutic trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(4):528–35.

Radstake T, van der Heijden E, Moret F, Hillen M, Lopes A, Rosenberg T. Clinical efficacy of leflunomide/hydroxychloroquine combination therapy in patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome: results of a placebo-controlled double-blind randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(10).

Seror R, Bowman S. Outcome measures in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Care Res. 2020;72(S10):134–49.

Brown S, Navarro Coy N, Pitzalis C, et al. The TRACTISS protocol: a randomised double blind placebo controlled clinical trial of anti-B-cell therapy in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:21.

Devauchelle-Pensec V, Mariette X, Jousse-Joulin S, et al. Treatment of primary Sjögren syndrome with rituximab: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(4):233–42.

Seror R, Bootsma H, Saraux A, et al. Defining disease activity states and clinically meaningful improvement in primary Sjögren’s syndrome with EULAR primary Sjögren’s syndrome disease activity (ESSDAI) and patient-reported indexes (ESSPRI). Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(2):382–9.

Bowman SJ, Booth DA, Platts RG, Field A, Rostron J. Validation of the Sicca symptoms inventory for clinical studies of Sjögren’s syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(6):1259–66.

Meiners PM, Arends S, Brouwer E, Spijkervet FK, Vissink A, Bootsma H. Responsiveness of disease activity indices ESSPRI and ESSDAI in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome treated with rituximab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(8):1297–302.

Moerman RV, Arends S, Meiners PM, et al. EULAR Sjogren’s syndrome disease activity index (ESSDAI) is sensitive to show efficacy of rituximab treatment in a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(2):472–4.

Quartuccio L, Salvin S, Fabris M, et al. BLyS upregulation in Sjogren’s syndrome associated with lymphoproliferative disorders, higher ESSDAI score and B-cell clonal expansion in the salivary glands. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52(2):276–81.

Heijden E, Blokland S, Hillen M, et al. Leflunomide–hydroxychloroquine combination therapy in patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome (RepurpSS-I): a placebo-controlled, double-blinded, randomised clinical trial. The Lancet Rheumatology. 2020;2.

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. In:2009.

US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-Focused Drug Development Guidance Series for Enhancing the Incorporation of the Patient’s Voice in Medical Product Development and Regulatory Decision Making. In:2018.

The US Food and Drug Administration. Patient Focused Drug Development Guidance Public Workshop: Select, Develop or Modify Fit for Purpose Clinical Outcomes Assessments. https://www.fda.gov/media/116277/download. Published 2018. Accessed 7 January 2022.

The US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-Focused Drug Development Guidance: Methods to Identify What Is Important to Patients, Guidance for Industry, Food and Drug Administration Staff, and Other Stakeholders. Draft guidance. https://www.fda.gov/media/131230/download Published 2019. Accessed 7 January 2022.

The US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-Focused Drug Development Guidance Public Workshop: Incorporating Clinical Outcome Assessments into Endpoints for Regulatory Decision Making. https://www.fda.gov/media/132505/download. Published 2019. Accessed 7 January 2022.

The US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-Focused Drug Development: Collecting Comprehensive and Representative Input, Guidance for Industry, Food and Drug Administration Staff and Other Stakeholders. https://www.fda.gov/media/139088/download Published 2020. Accessed 7 January 2022.

van der Heijden EHM, Blokland SLM, Hillen MR, et al. Leflunomide–hydroxychloroquine combination therapy in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome (RepurpSS-I): a placebo-controlled, double-blinded, randomised clinical trial. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2(5):e260–9.

Baer AN, Gottenberg J-E, St Clair EW, et al. Efficacy and safety of abatacept in active primary Sjögren’s syndrome: results of a phase III, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(3):339–48.

Fisher BA, Szanto A, Ng W-F, et al. Assessment of the anti-CD40 antibody iscalimab in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2(3):e142–52.

The US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. In:2009.

The US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-Focused Drug Development Guidance Series for Enhancing the Incorporation of the Patient’s Voice in Medical Product Development and Regulatory Decision Making. In:2018.

Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. Sage publications; 2004.

ATLAS.ti.Scientific Software Development GmbH B, Germany. Atlas.ti.software version 7. 2013.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Public Policy Committee. International Society of Pharmacoepidemiology. Guidelines for good pharmacoepidemiology practice (GPP) Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25:2–10.

Vandenbroucke JP, Von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10): e297.

World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki - ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/. Published 2013. Accessed 7 January 2022.

Patel R, Shahane A. The epidemiology of Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Epidemiol 6: 247–255. In:2014.

Wratten S, Flynn J, Cooper C, et al. Patient and Physician Response Scale Preferences for Clinical Outcome Assessments in Sjogren's: A Qualitative Comparison of Visual Analogue Scale, Numerical Rating Scale, and Likert Scale Response Options. ISPOR Europe 2021; 2021; Copenhagen, Denmark.

Wratten S, Abetz-Webb L, Arenson E, et al. Exploring Alternative Responder Definitions for EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient Reported Index (ESSPRI) for Use in Sjögren’s Clinical Trials [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73.

Wratten S, Griffiths N, Cooper C, et al. Sjögren’s Syndrome Symptom Diary (SSSD) and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) as Assessments of Symptoms in Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Qualitative Exploration of Content Validity and Meaningful Change [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73.

Izmirly PM, Buyon JP, Wan I, et al. The incidence and prevalence of adult primary Sjögren’s syndrome in New York county. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71(7):949–60.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients and physicians who took part in this research. The authors would also like to thank Natasha Griffiths of Adelphi Values for her role in data collection and analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Adelphi Values were commissioned by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland to conduct this study. Novartis also funded the Rapid Service Fee.

Author contributions

C.C. contributed to the conception or design of the study, conducted physician interviews, contributed substantially to the data analysis and interpretation, was a major contributor in writing the manuscript, and provided final approval of the publication. C.C. is a former employee of Adelphi Values and was employed by Adelphi Values during the conduct of this study. S.W. contributed to the conception or design of the study, contributed substantially to the data analysis and interpretation, and provided critical review and final approval of the publication. S.W. is a former employee of Adelphi Values and was employed by Adelphi Values during the conduct of this study. R.W.H. contributed to the conception or design of the study, contributed substantially to the data analysis and interpretation, and provided final approval of the publication. A.B. contributed to the data analysis and interpretation and provided critical review and final approval of the publication. B.N. contributed to the conception or design of the study, contributed to the data analysis and interpretation, and provided critical review and final approval of the publication. W.H. contributed to the conception or design of the study, contributed to the data analysis and interpretation, and provided critical review and final approval of the publication. P.G. contributed to the conception or design of the study, contributed to the data analysis and interpretation, and provided critical review and final approval of the publication.

Prior presentation

This manuscript is based on work that was previously published as a conference abstract and presented as a poster at ACR Convergence 2021 [Wratten S., Cooper C., Flynn J., Griffiths N., Hall R., Abetz-Webb L., Bowman S., Hueber W., Ndife B., Goswami P. Patient and Physician Perspectives on EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient Reported Index (ESSPRI) and EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI): A Qualitative Interview Study [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021; 73 (suppl 10). https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/patient-and-physician-perspectives-on-eular-sjogrens-syndrome-patient-reported-index-esspri-and-eular-sjogrens-syndrome-disease-activity-index-essdai-a-qualitative-interview-stu/. Accessed 8 August 2022].

Disclosures

Rebecca Williams-Hall is an employee of Adelphi Values, a health outcomes agency commissioned by Novartis to conduct this research. At the time of the study, Carl Cooper and Samantha Wratten were also employed by Adelphi Values, but are currently employees of Evidera Ltd and IQVIA, respectively. Arthur Bookman is a Principal Investigator recruiting patients for Novartis-sponsored clinical trials. Briana Ndife, Wolfgang Hueber and Pushpendra Goswami are employed by Novartis.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Ethical approval and oversight was provided by Salus Independent Review Board (IRB), a centralised IRB in the USA (physician protocol ID: NO9051A; patient protocol ID: NO9052A). All participants provided oral and written informed consent prior to the conduct of any research activities. Both studies were designed and conducted in accordance with best practice guidelines and the ethical principles laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available owing to participants consenting to data being published in aggregated form and full interview recordings/transcripts only being available to the project team responsible for conducting the research.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cooper, C., Wratten, S., Williams-Hall, R. et al. Qualitative Research with Patients and Physicians to Assess Content Validity and Meaningful Change on ESSDAI and ESSPRI in Sjögren’s. Rheumatol Ther 9, 1499–1515 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-022-00487-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-022-00487-0