Abstract

The act of nonmedical switching, defined as switching stable patients who are generally doing well with their current therapy from an originator biologic to its biosimilar, has been endorsed as a reasonable treatment strategy. The safety and efficacy of nonmedical switching have been evaluated in randomized controlled and real-world evidence studies, which have demonstrated that although many patients maintain treatment response after the switch, some patients experience therapy failure, resulting in therapy discontinuation. It has been postulated that the vast majority, if not all, of these treatment failures result from a “nocebo effect”, defined as patients’ negative expectations toward the therapy change. Reports suggest that the risk of a nocebo effect is higher following a mandated nonmedical switch. Although the nocebo effect is a well-recognized phenomenon in pain studies, evidence is limited in immune-mediated diseases primarily because it is difficult to quantify, especially retrospectively. In spite of this, numerous biosimilar studies in patients with immune-mediated diseases have concluded that nonmedical switching failures are due to a nocebo effect. The objective of this narrative review was to explore the reasons for nonmedical switch failure or discontinuation and the role of the nocebo effect among patients with inflammatory rheumatic and gastrointestinal diseases who switched from an originator biologic to its biosimilar.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This article explores the possibility that a nocebo effect may be a contributing factor for loss of efficacy and/or adverse outcomes following a nonmedical switch from an originator biologic to its biosimilar. |

The reviewed evidence suggests that some patients who lose efficacy or have an adverse event after a nonmedical switch to a biosimilar may regain treatment control by switching back to the originator therapy. |

Overall, more robust and well-designed nonmedical switching studies are needed to evaluate the impact of the nocebo effect. |

Patient education may help minimize misconceptions about therapy changes and prevent or reduce nocebo effect. |

Based on the current evidence, patients who switch to a biosimilar and lose treatment response or experience an adverse event should have the right to reestablish therapy with the originator, taking into consideration any associated potential immunogenic risks. |

Introduction

The introduction of biologic therapies has resulted in substantial benefits in the treatment of chronic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) [1, 2]. The recent introduction of biosimilars, biologic therapeutics that are highly similar but not identical to their respective originator biologic products [3, 4], has changed the treatment landscape of chronic IMIDs by providing patients with additional, presumably more accessible, therapeutic options [5]. The demonstration of biosimilarity does not require all aspects of the biosimilar and originator products to be identical; however, biosimilars undergo a rigorous comparative preapproval testing process, with approval based on the totality of the resulting evidence that shows a high degree of similarity between the originator and biosimilar [3, 4]. Multiple reports from head-to-head trials in rheumatic diseases have demonstrated that treatment of biologic-naive patients with either an originator biologic or its biosimilar resulted in generally similar efficacy and safety profiles. Approximately 70% of patients achieved a predefined clinical response on the primary efficacy endpoints (usually an American College of Rheumatology 20% improvement response [ACR20] [6]) with both the originator and the biosimilar [7,8,9,10]. Of note, biosimilar clinical trials are powered for efficacy; safety or immunogenicity has not been a primary endpoint in any biosimilar clinical trial with most of them having no more than 350 patients per arm.

In some countries and among some payers, the act of nonmedical switching from an originator product to its biosimilar (or vice versa) has been mandated as a treatment strategy in patients who are stable and generally doing well with the originator biologic [11,12,13,14]. Nonmedical switching is often driven by economic reasons [2, 5], and the practice has been deemed reasonable in patients with IMIDs based on several tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor studies [14,15,16]. However, there has been criticism of these studies for not being properly controlled and failing to include well-defined, meaningful endpoints [17]. The key study supporting nonmedical switching is NOR-SWITCH, a Norwegian nationwide randomized controlled trial (RCT) that investigated switching from the originator infliximab to its biosimilar CT-P13 versus continued use of the originator in patients with stable control of IMID for a minimum of 6 months. The primary endpoint was the noninferiority of switching compared with not switching as assessed by disease worsening not more than 30% in the pooled cohort of six IMIDs (32% with Crohn’s disease, 19% with ulcerative colitis, 19% with spondyloarthritis, 16% with rheumatoid arthritis, 7% with chronic plaque psoriasis, and 6% with psoriatic arthritis). The overall discontinuation rates were similar between patients who switched and those who did not (8% vs. 10%; Fig. 1a), and disease worsening rates fell within the prespecified noninferiority margin of 15% in the pooled analysis (26% for patients who continued on originator and 30% for those who switched) [14]. Although the study was not powered to show noninferiority in individual diseases, five out of the six IMID cohorts did not meet the prespecified non-inferiority margin for disease worsening; a critical appraisal of the design issues and difficulties in interpreting the NOR-SWITCH study has been published elsewhere [18]. In several other RCT switching studies, similar discontinuation rates were generally observed between non-switch and switch groups among biologic-naive patients who were failing methotrexate (Fig. 1a) [15, 16, 19,20,21,22].

Proportion of patients who discontinued therapy after switch from the originator therapy to biosimilar (switch group) versus the control group in a randomized controlled trials and b real-world evidence studies. aControl group consisted of patients who continued on originator therapy. bControl group consisted of patients who continued on biosimilar therapy. cControl group consisted of historical cohort. C control group, S switch group

The safety and efficacy of nonmedical switching have also been investigated in several real-world evidence (RWE) studies of infliximab and etanercept [11, 13, 23,24,25,26]. Although these studies generally reported favorable outcomes, higher risk of failure or treatment withdrawal was observed in some of these studies among patients who switched compared with those who continued the originator therapy [11, 13, 26]. Of interest, several studies allowed switchback to the originator therapy after nonmedical switch failure and demonstrated that patients often regain efficacy or experience resolution of adverse events after resuming the originator therapy [27,28,29]. These findings suggest that some patients do not maintain treatment response following a nonmedical switch, leading to higher discontinuation rates than would be expected without a switch. However, the reasons for these failures have not been well investigated.

Nocebo Effect

It has been suggested that treatment failure following a nonmedical switch results from a “nocebo effect” [28]. The nocebo effect was first described in the 1960s and is defined as a negative outcome or failure of therapy (e.g., disease worsening or occurrence of a new or worsening adverse event) resulting from a patient’s negative expectations toward a new therapy or a change in therapy [30]. Although most research into this effect has been done in the area of pain [31], the nocebo effect has also been reported in clinical drug trials and clinical practice in patients with other diseases [31, 32]. Reports have demonstrated that disclosure of potential side effects of a therapy may result in occurrence of that effect, independent of the pharmacologic characteristics of the drug [31]. Switching therapies may also negatively impact medication adherence and could be associated with poorer clinical outcomes [32]. In some instances, although initial cost savings were achieved with switching, the total overall cost of care increased because of increased physician visits or hospitalizations [32]. The nocebo effect can be influenced by the manner in which information is presented to the patient. Communication between the physician and patient can play a major role in the patient’s treatment expectations and, consequently, have either a positive or a negative impact on the outcome of medical therapy [33, 34]. In contrast, a positive consequence, or placebo effect, is the more well-known aspect of the phenomenon that results when a patient expects, and therefore experiences, a positive outcome, even with a sham treatment [35].

Treatment discontinuations among patients who undergo nonmedical switch from an originator TNF inhibitor to its biosimilar and subsequent failure to maintain treatment response or experience an adverse event could be explained by the nocebo effect in many instances. This has been reported particularly following a mandated nonmedical switch in stable patients who had been doing well with their previous therapy [11, 36,37,38,39]. However, the current evidence regarding this is limited, as it is difficult to identify or quantify, especially retrospectively. RWE studies often lack adequate design (such as lack of control groups and high heterogeneity across patient populations and trials) and do not collect all the data needed to assess the reasons for treatment failure (i.e., whether it was due to the disease course or the nonmedical switch from the originator to the biosimilar). Furthermore, the definition of flare can be problematic. In patients with RA, for example, a definition of a flare can be assessed either by clinical disease activity or by patient-reported outcomes, and different definitions of flare with varying levels of sensitivity/specificity and validation have been used across trials. To assess clinical disease activity, at a minimum, the patient should be evaluated via a 28-joint count, an inflammatory marker (e.g., C-reactive protein), and possibly an ultrasound evaluation of the joints to evaluate subclinical joint inflammation; however, these metrics were not uniformly obtained in the controlled clinical trials, let alone RWE studies. A recent critique of the DANBIO registry highlighted some of the methodological defects of a mandatory nonmedical switching study that limited the evidence and suggested that the results cannot be translated to carry out nonmedical switching in clinical practice [40].

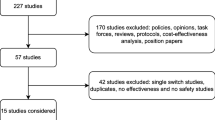

To explore the possibility of a nocebo effect following a nonmedical switch between an originator TNF inhibitor and its biosimilar, we assessed the current evidence from existing RCTs and RWE studies (from both published articles and congress abstracts) that investigated nonmedical switching from originators infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab to their respective biosimilars in patients with rheumatic or gastrointestinal IMIDs. Because no validated metric exists to detect a nocebo effect, we used discontinuation data and rate of switching back to the originator biologic after the switch as surrogate indicators of treatment failure following a nonmedical switch.

Literature Search

A literature search of databases, including Embase® and MEDLINE®, was performed to identify nonmedical switching studies. The search was limited to English language, humans, and publication dates from January 1, 2012, to February 21, 2019; both original papers and congress abstracts were included. Studies were included if they fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: investigated switch from an originator TNF inhibitor to its biosimilar in patients with rheumatic or gastrointestinal IMIDs and reported either discontinuation data for RCTs or switchback data for RWE studies. Switchback data were defined as percentage of patients who switched back to the originator after a failure of a nonmedical switch from the originator to its biosimilar. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Discontinuation Following a Nonmedical Switch

A total of ten RCTs (adalimumab, two studies; etanercept, one study; infliximab, seven studies) [14,15,16, 19,20,21,22, 41,42,43] and 37 RWE studies (etanercept, 15 studies; infliximab, 22 studies [one study reported data separately for infliximab and etanercept and was counted twice]) [12, 13, 23,24,25, 27, 28, 36, 37, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70] in patients with rheumatic or gastrointestinal IMIDs were identified (Table 1).

In the RCTs, discontinuation rates ranged from 5 to 33% in the switch groups and from 4 to 18% in the control group (Fig. 1a). Adverse events and withdrawal of consent were generally the most commonly reported reasons for discontinuation. The discontinuation rates were similar between the switch and control groups with the exception of one study that reported high discontinuation rate for the switch group (33%) versus the control group (16%) [43].

Among the RWE studies, discontinuation rates after the nonmedical switch also varied widely, ranging from 3 to 87% (median, 22%) among the 22 infliximab studies and from 8 to 33% (median, 17%) among the ten etanercept studies (Table 2). In general, the discontinuation rates in the rheumatic disease studies varied more widely (median [range], 18% [3–87%]) compared with the IBD studies (20% [10–29%]); however, only four IBD studies were assessed compared with 26 rheumatic disease studies (Table 2).

Seven RWE studies included a control group [13, 37, 61, 62, 64, 65, 68]; of these, notably greater proportions of patients in the switch groups discontinued therapy in four studies (range, 24–87%) compared with the control groups (range, 5–38%; Fig. 1b) [61, 62, 64, 65]. In the remaining three studies, the discontinuation rates were either similar between the groups (10% vs. 8% and 29% vs. 26%) or lower in the switch group versus the control group (18% vs. 33%) [13, 37, 68]. In the latter study (DANBIO), the switchers in general had lower disease activity at baseline and received concomitant methotrexate more frequently than non-switchers [37]. When compared with the historic cohort, the baseline characteristics were similar to the switchers, while the 1-year crude retention rate was lower among the switchers (82%) versus the historic cohort (88%) [37].

The most commonly reported reasons for biosimilar discontinuation in the RWE studies included loss of response/inefficacy, adverse events, or subjective reasons/nocebo effect. However, based on the information provided, it is impossible to distinguish whether the loss of efficacy or adverse events that led to discontinuation were caused by the pharmacologic activity, or lack thereof, of the biologic itself or by switching-related factors such as a nocebo effect. The rationale for attributing these discontinuations to subjective reasons or nocebo effect was based on the patients’ use of subjective complaints (typically described as the patients subjectively feeling worse without objective deterioration of disease activity), rather than objective measures of worsening. However, subjective patient-reported complaints are demonstrated to be as valid as objective measures in determining whether a medication differs from placebo and are equally important in assessing therapy success in patients with RA [71]. Appropriately designed studies have not yet been performed and are needed in the future to assess the exact reasons for discontinuation and the potential contribution of the nocebo effect to discontinuation rates. Studies, if any, assessing the way to prevent the nocebo effect or its success have not been published.

It is noteworthy that discontinuation rates in historical controls may include not only stable patients who have received the originator for at least 1 year but also patients who have only recently begun treatment [61]. It has been shown that 12-month retention rates increase incrementally with each subsequent year of treatment in patients receiving etanercept or infliximab with rheumatic or psoriatic diseases [72, 73], suggesting that patients who have received at least 1 year of biologic therapy are less likely to discontinue treatment than patients initiating therapy. Of the RWE studies reviewed here, the median duration on the originator before the nonmedical switch ranged from 4 to 8 years on originator infliximab and 4 to 6 years on originator etanercept (Table 1). Because these patients had largely received originator treatment for at least 1 year, it can be inferred that the discontinuation rates following these patients’ nonmedical switch to a biosimilar might be expected to be lower than those reported by any historical comparator group. Interestingly, the discontinuation rates following a nonmedical switch were similar to those newly initiating TNF inhibitor therapy. The pooled discontinuation rates after a nonmedical switch were 17% (0–6 months after switch), 25% (6–12 months after switch) and 30% (> 12 months after switch) compared with an overall discontinuation rate of 21, 27, 37, and 50% at 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 5 years, respectively, reported with TNF inhibitors [74].

Switchback to Originator Therapy

The overall incidence of switchback ranged from 1 to 72% (median, 11%) in the 22 infliximab studies and from 3 to 20% (median, 7%) in the 15 etanercept studies (Table 2). When assessing the rate only among those patients who discontinued therapy, the incidence of switchback ranged from 3 to 100% (median, 59%) among infliximab and etanercept studies; in six studies, 100% of patients who discontinued biosimilar therapy switched back to the originator (Fig. 2) [23, 24, 45, 54, 56, 60].

The reasons postulated for switchback included subjective reasons/nocebo response, loss of response/inefficacy, and adverse events (Table 2). Among the 12 studies that provided data for switchback success, 50 to 100% (median, 80%) of patients successfully resumed originator therapy. Although some reports have suggested that regaining clinical disease control or resolving adverse effects following switchback to the originator therapy was due to reversal of the nocebo effect [11, 28, 59, 61], without adequately controlled studies, other reasons (such as objective loss of efficacy or emergence of adverse events resulting from switch in therapy) cannot be excluded. Overall, these results demonstrate that a reasonable number of patients do not respond to nonmedical switch from originator TNF inhibitor to its biosimilar and switching back to the originator allows a majority of these patients to regain treatment response.

Patients’ Choice To Switch

Some healthcare systems have introduced practices that involve involuntary switching for nonmedical reasons from originators to their biosimilars. In Europe, pharmacy-level substitution of originators to biosimilars is already possible in Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Poland, Serbia, and Turkey (although physicians can opt out in each country), whereas nonmedical switching is currently allowed in 12 European countries (with or without the treating physician’s consent) and the practice is likely to become more widespread in the future [75]. Because forced switching may exacerbate negative patient expectations, we investigated published reports to ascertain whether there are patterns of nonmedical switching failures based on voluntary versus nonvoluntary switching. Among the 37 RWE infliximab and etanercept studies evaluated, 11 allowed patients to choose whether to switch, ten studies did not allow patients to choose or “restricted” their choice, and the remaining 16 studies did not specify whether switching was voluntary (Table 2). In general, infliximab biosimilar discontinuation was numerically higher in the six studies in which it was mandated or patients’ choice to switch was restricted (range, 7–29%; median, 23%) compared with the eight studies that allowed patients to choose whether to switch or not (range, 7–24%; median, 16%). A similar pattern was observed in the three etanercept switching studies that mandated or restricted patients’ choice to switch (range, 8–33%; median, 18%) compared with the three studies that allowed patients to choose whether to switch (range, 10–25%; median, 14%; Table 2). Similarly, a higher percentage of patients who discontinued therapy switched back to the originator in studies that mandated or restricted choice to switch in the six infliximab (median [range], 78% [5–100%]) and three etanercept (50% [40–71%]) studies compared with the eight infliximab (53% [20–80%]) and three etanercept (28% [25–71%]) studies that allowed patients to choose. However, the rates were still high for patients who could choose.

Although forced switching may intensify negative expectations and contribute to higher discontinuation rates secondary to the possibility of a nocebo effect, it is reasonable to consider that not all discontinuations are due to nocebo effect. As there was no statistical analysis or detailed information on the patients’ extent of freedom to choose or refuse to switch, it is difficult to draw any definite conclusion from these reports. Furthermore, one could reasonably postulate that, rather than experiencing a nocebo effect, some patients may have simply experienced a loss of efficacy or an adverse event when switched to a molecule that, although similar, was not identical. Nonetheless, forced switching raises ethical issues, and any nonmedical therapy switch should be conducted only in agreement with the patient and treating physician.

Patient Education

As nocebo effect is shown to be influenced by the nature of communication between a physician and patient, which subsequently can set patient’s treatment expectations [33], informed and standardized patient education and sharing of adequate information are vital in making informed decisions regarding nonmedical switch and minimizing misconceptions about therapy changes and biosimilars [76,77,78]. A recent study assessing knowledge among patients with rheumatic diseases revealed that 65% of all patients and 66% of those receiving a biosimilar did not feel sufficiently informed about biosimilars [79]. In addition, among patients who were switched from the originator to a biosimilar, 38% were either not informed of the switch or were not asked their consent to the switch. This is alarming, especially when considering that understanding what biosimilarity means and receiving adequate information about biosimilars were associated with better biosimilar treatment adherence [79]. However, it should be noted that providing verbal or written communication before a switch may not guarantee positive outcomes, which was observed in the RWE studies reviewed. As reported in multiple studies, patients who were persuaded or urged to switch (i.e., restricted choice) and who received face-to-face consultation and/or written information regarding the switch and the biosimilar before the switch still had a considerably high incidence of discontinuation (7–29%) and switchback (5–100%) in most of these studies [56, 57, 60, 61, 68, 69, 80]. This may be associated with an erroneous belief that biosimilars are lesser quality or have lower efficacy and safety than their originators [79, 81]. A recent review of nocebo effect following switching from originator TNF inhibitors to their biosimilars proposed the use of a consistent lexicon and language-use guideline, with the goal of ensuring unified communications around biosimilar medications [76]. However, although this approach may unify messaging and reduce miscommunication, it will not address reasons for treatment failure following a nonmedical switch that are not attributable to nocebo effect.

Is It Nocebo or True Loss of Efficacy/Adverse Effects?

As we have suggested previously, nocebo effect may explain a considerable number of treatment failures following a nonmedical switch, but one cannot exclude other reasonable explanations for the worsening of disease outcomes or occurrence of adverse events secondary to the switch. Because biologics are complex, micro-heterogeneous molecules that are highly sensitive to changes in both raw materials and manufacturing conditions, differences between biosimilars and their originator products can and do exist [82,83,84]. Although the clinical effect of these differences are not fully known, it is reasonable to postulate that the differences can cause individuals to respond differently to each molecule and raises the distinct possibility of altered outcomes that cannot be ignored [83, 85]. Potential immunogenic responses should also be acknowledged; because biosimilars are not exact copies of their originators, it has been suggested that switching to a biosimilar may trigger an immunogenic response to subtle differences in epitopes between biosimilar and the originator [4, 84, 86], potentially leading to loss of efficacy or adverse events in individual patients [85]. Furthermore, some studies have demonstrated that patients who develop an immunogenic response against an originator biologic should not be switched to its biosimilar owing to cross-reactivity and thus a similar loss of treatment response [87,88,89,90]. To our knowledge, only one pooled analysis has assessed the associations between immunogenicity and adverse outcomes [85], and future studies are needed to fully assess the implications of immunogenic consequences on efficacy and safety following a nonmedical switch but also responses that go beyond immunogenicity (e.g., nocebo effect).

Currently, the question of whether all patients who develop an adverse event or lose efficacy after a switch to a biosimilar is due to a nocebo effect or differences between the originator and biosimilar cannot be answered owing to lack of well-designed, prospective and properly conducted, blinded clinical trials with appropriate control groups that could accurately investigate this question. In such trials, at minimum, patients should be randomized to groups that continue with the originator biologic, continue with the biosimilar, and switch from the originator to the biosimilar and vice versa multiple times, with a rescue option to use the original therapy in the event of therapeutic failure [91]. In addition, the cause of failure should be judiciously examined. A well-designed nocebo trial should also implement a questionnaire or a training system for physicians and nurses to avoid the nocebo effect. Until reliable evidence from such studies are available, distinguishing whether negative treatment outcomes are due to a nocebo effect versus loss of efficacy or an adverse event simply because they are not taking the same medication will continue to be challenging. For this reason, patients should be involved in the decision to switch. Of note, when physicians approach patients regarding nonmedical switching, one of the first obstacles they face is to explain that the reason for the therapy change is financial and not medical [92]. In addition, major concerns still exist among rheumatologists and gastroenterologists; a survey in the United States found that 84% of physicians did not support a switch involving stable patients [93]. Furthermore, a majority (> 57%) of physicians anticipated negative impacts on efficacy, safety and patient’s mental health following a nonmedical switch, supporting the need of well-designed studies to assess the impact of such switches [93].

The limitations of this review include that it was narrative in nature rather than a more rigorous systematic review. The review was restricted to rheumatic diseases and IBD owing to the authors’ expertise and because of the limited availability of published, fully peer-reviewed articles. Due to this, we included congress abstracts (including all etanercept RWE studies), which are restricted in the amount of study data that can be reported. Another limitation is that these analyses relied on how the original study authors categorized discontinuations; caution is therefore warranted when interpreting these data.

Conclusions

The nocebo effect in nonmedical switching from an originator biologic to its biosimilar may be a contributing factor for loss of efficacy or adverse outcomes following the switch but does not explain all failures. Some patients who fail a nonmedical switch may regain treatment control by switching back to the originator therapy. Discontinuation and switchback rates were somewhat higher in studies that did not allow patients to choose whether to switch therapies, suggesting that forced switching may intensify negative expectations and contribute to a higher rate of therapy discontinuation. However, due to the inconsistency and a lack of robustness among the studies conducted to date, it is difficult to estimate the true rate of nocebo response. More well-designed nonmedical switching studies are needed to evaluate the true impact of the nocebo effect.

Although patient education is vital in making informed decisions regarding a treatment switch and minimizing misconceptions about therapy changes, treatment failures have been observed even when consultation and information regarding the switch were provided before switching. This finding suggests that more emphasis be placed on communication about nonmedical switching in general and allow for the fact that treatment failures may occur following a switch from an originator to a biosimilar irrespective of a nocebo effect. Regardless of whether discontinuation of therapy following a switch is due to the nocebo effect or other causes, the final outcome is an increase in the total cost of care because of increased physician visits or hospitalizations. Thus, better understanding of the causes for discontinuation may help prevent it and ultimately lead to cost reduction. If a nocebo effect is occurring in some patients, strategies are needed to predict or minimize it (e.g., effective patient education) and to separate it from other reasons for which patients may not be responding to the switch. Any decision to switch would be better done in agreement with the patient and their treating physician. Furthermore, based on current evidence, patients who switch and lose treatment response or have an adverse event should have the option to reestablish therapy with the originator. With biosimilars continuing to enter the market, understanding the potential reasons leading to nonmedical switch failures will enable providers to take appropriate steps to lower or prevent them.

References

Côté-Daigneault J, Bouin M, Lahaie R, Colombel JF, Poitras P. Biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: what are the data? United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:419–28.

Reynolds A, Koenig AS, Bananis E, Singh A. When is switching warranted among biologic therapies in rheumatoid arthritis? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12:319–33.

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on similar biological medicinal products (Revision). CHMP/437/04 Rev 1. London, UK: 2014.

US Department of Health and Human Services, US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: scientific considerations in demonstrating biosimilarity to a reference product. Rockville: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015.

Moots R, Azevedo V, Coindreau JL, et al. Switching between reference biologics and biosimilars for the treatment of rheumatology, gastroenterology, and dermatology inflammatory conditions: considerations for the clinician. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;19:37.

Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, et al. American College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:727–35.

Park W, Hrycaj P, Jeka S, et al. A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, parallel-group, prospective study comparing the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of CT-P13 and innovator infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: the PLANETAS study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1605–12.

Yoo DH, Hrycaj P, Miranda P, et al. A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study to demonstrate equivalence in efficacy and safety of CT-P13 compared with innovator infliximab when coadministered with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: the PLANETRA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1613–20.

Weinblatt ME, Baranauskaite A, Niebrzydowski J, et al. Phase III randomized study of SB5, an adalimumab biosimilar, versus reference adalimumab in patients with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2018;70:40–8.

Emery P, Vencovský J, Sylwestrzak A, et al. A phase III randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study comparing SB4 with etanercept reference product in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:51–7.

Glintborg B, Sørensen IJ, Loft AG, et al. A nationwide non-medical switch from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 in 802 patients with inflammatory arthritis: 1-year clinical outcomes from the DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1426–31.

De Cock D, Kearsley-Fleet L, Watson K, Hyrich KL. Switching from RA originator to biosimilar in routine clinical care: early data from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:3489–91.

Tweehuysen L, Huiskes VJB, van den Bemt BJF, et al. Open-label non-mandatory transitioning from originator etanercept to biosimilar SB4: 6-month results from a controlled cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2018;70:1408–18.

Jørgensen KK, Olsen IC, Goll GL, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR-SWITCH): a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2304–16.

Park W, Yoo DH, Miranda P, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching from reference infliximab to CT-P13 compared with maintenance of CT-P13 in ankylosing spondylitis: 102-week data from the PLANETAS extension study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:346–54.

Yoo DH, Prodanovic N, Jaworski J, et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13 (biosimilar infliximab) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: comparison between switching from reference infliximab to CT-P13 and continuing CT-P13 in the PLANETRA extension study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:355–63.

Numan S, Faccin F. Non-medical switching from originator tumor necrosis factor inhibitors to their biosimilars: systematic review of randomized controlled trials and real-world studies. Adv Ther. 2018;35:1295–332.

Faccin F, Tebbey P, Alexander E, Wang X, Cui L, Albuquerque T. The design of clinical trials to support the switching and alternation of biosimilars. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2016;16:1445–53.

Cohen SB, Alonso-Ruiz A, Klimiuk PA, et al. Similar efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of adalimumab biosimilar BI 695501 and Humira reference product in patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis: results from the phase III randomised VOLTAIRE-RA equivalence study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:914–21.

Weinblatt ME, Baranauskaite A, Dokoupilova E, et al. Switching from reference adalimumab to SB5 (adalimumab biosimilar) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: fifty-two–week phase III randomized study results. Arthritis Rheum. 2018;70:832–40.

Emery P, Vencovský J, Sylwestrzak A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis continuing on SB4 or switching from reference etanercept to SB4. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1986–91.

Smolen JS, Choe JY, Prodanovic N, et al. Safety, immunogenicity and efficacy after switching from reference infliximab to biosimilar SB2 compared with continuing reference infliximab and SB2 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results of a randomised, double-blind, phase III transition study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:234–40.

Babai S, Akrout W, Le-Louet H. Reintroduction of reference infliximab product in patients showing inefficacy to its biosimilar [abstract]. Drug Saf. 2017;40:1027–8.

Gentileschi S, Barreca C, Bellisai F, et al. Switch from infliximab to infliximab biosimilar: efficacy and safety in a cohort of patients with different rheumatic diseases. Response to: Nikiphorou E, Kautiainen H, Hannonen P, et al. Clinical effectiveness of CT-P13 (infliximab biosimilar) used as a switch from Remicade (infliximab) in patients with established rheumatic disease. Report of clinical experience based on prospective observational data. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15:1677–83.

Dyball S, Hoskins V, Christy-Kilner S, Haque S. Effectiveness and tolerability of Benepali in rheumatoid arthritis patients switched from Enbrel [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:3505–6.

Chaparro M, Garre A, Guerra Veloz MF, et al. P0978 Effectiveness and safety of the switch from remicade to CT-P13 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:A453.

Hendricks O, Hørslev-Petersen K. When etanercept switch fails—clinical considerations [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:3570–1.

Boone NW, Liu L, Romberg-Camps MJ, et al. The nocebo effect challenges the non-medical infliximab switch in practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74:655–61.

Steel L, Marshall T, Loke M. THU0204-Real world experience of biosimilar switching at the Norfolk & Norwich University Hospital, United Kingdom. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:321.

Kennedy WP. The nocebo reaction. Med World. 1961;95:203–5.

Colloca L, Miller FG. The nocebo effect and its relevance for clinical practice. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:598–603.

Straka RJ, Keohane DJ, Liu LZ. Potential clinical and economic impact of switching branded medications to generics. Am J Ther. 2017;24:e278–89.

Häuser W, Hansen E, Enck P. Nocebo phenomena in medicine: their relevance in everyday clinical practice. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:459–65.

Pouillon L, Socha M, Demore B, et al. The nocebo effect: a clinical challenge in the era of biosimilars. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:739–49.

Colloca L. The fascinating mechanisms and implications of the placebo effect. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2018;138:15–20.

Sigurdardottir VR, Svärd A. THU0222 Multiswitching—from reference product etanercept to biosimilar and back again—real-world data from a clinic-wide multiswitch experience [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:A331.

Glintborg B, Loft AG, Omerovic E, et al. To switch or not to switch: results of a nationwide guideline of mandatory switching from originator to biosimilar etanercept. One-year treatment outcomes in 2061 patients with inflammatory arthritis from the DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:192–200.

Sieczkowska J, Jarzębicka D, Banaszkiewicz A, et al. Switching between infliximab originator and biosimilar in paediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease: preliminary observations. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:127–32.

Rabbitts R, Jewell T, Marrow K, Herbison C, Laversuch C. Switching to biosimilars: an early clinical review [abstract]. Rheumatology. 2017;56:132.

Cantini F, Benucci M. Mandatory, cost-driven switching from originator etanercept to its biosimilar SB4: possible fallout on non-medical switching. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018.

Roder H, Schnitzler F, Borchardt J, Janelidze S, Ochsenkühn T. P0984 Switch of infliximab originator to biosimilar CT-P13 in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a large german IBD center. A one year, randomized and prospective trial. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:A456.

Matsuno H, Matsubara T. A randomized double-blind parallel-group phase III study to compare the efficacy and safety of NI-071 and infliximab reference product in Japanese patients with active rheumatoid arthritis refractory to methotrexate. Mod Rheumatol. 2018;29:1–26.

Tanaka Y, Yamanaka H, Takeuchi T, et al. Safety and efficacy of CT-P13 in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis in an extension phase or after switching from infliximab. Mod Rheumatol. 2017;27:237–45.

Alten R, Jones H, Curiale C, Meng T, Lucchese L, Miglio C. SAT0201 Real world evidence on switching between etanercept and its biosimilar in rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:961.

De Cock D, Davies R, Kearsley-Fleet L, et al. P34 Biosimilar use in children and young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a real-world setting in the United Kingdom. Rheumatology. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key273.036.

Hoque T, Suddle A, Herdman L, Kitchen J. 072 Patient perceptions of switching to biosimilars. Rheumatology. 2018;57:key075.

Lee S, Szeto M, Galloway J. AB1267 Bio-similar to bio-originator switchback: not a reliable quality indicator. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1727–8.

Müskens WD, Rongen-van Dartel SAA, Adang E, van Riel PL. AB0475 The influence of switching from etanercept originator to its biosimilar on effectiveness and the impact of shared decision making on retention and withdrawal rates [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:A1399.

Patel D, Ahmed TJ, Levy S, Rajak R, Sathananthan R, Horwood N. e55 Analysis of rheumatoid arthritis patients who failed the switch from originator etanercept to biosimilar etanercept in Croydon. Rheumatology. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key075.596.

Scherlinger M, Langlois E, Germain V, Schaeverbeke T. Acceptance rate and sociological factors involved in the switch from originator to biosimilar etanercept (SB4). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48:927–32.

Shah K, Flora K, Penn H. 232 Clinical outcomes of a multi-disciplinary switching programme to biosimilar etanercept for patients with rheumatoid arthritis [abstract]. Rheumatology. 2018;57(key075):456.

Smith R, Fawthrop F. 063 Similar experience of biosimilars: a review of Rotherham Hospital’s experience of switching from enbrel to benepali. Rheumatology. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key075.287.

Abdalla A, Byrne N, Conway R, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of biosimilar infliximab among patients with inflammatory arthritis switched from reference product. Open Access Rheumatol. 2017;9:29–35.

Forejtová S, Zavada J, Szczukova L, Jarosova K, Philipp T, Pavelka K. A non-medical switch from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 in 36 patients with ankylosing spondylitis: 6-months clinical outcomes from the Czech biologic registry ATTRA [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:2198–201.

Germain V, Scherlinger M, Barnetche T, Schaeverbeke T, Federation Hospitalouniversitaire A. Long-term follow-up after switching from originator infliximab to its biosimilar CT-P13: the weight of nocebo effect. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018.

Holroyd C, Parker L, Bennett S, et al. O52 Switching to biosimilar infliximab: real-world data from the Southampton biologic therapies review service [abstract]. Rheumatology. 2016;55:i60–1.

Layegh Z, Ruwaard J, Hebing RC, et al. AB1279 Efficacious transition from reference product infliximab to the biosimilar in daily practice [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:A1733.

Malaiya R, McKee Z, Kiely P. Infliximab biosimilars—switching Remicade to Remsima in routine care: patient acceptability and early outcome data [abstract]. Rheumatology. 2016;55:158.

Nikiphorou E, Kautiainen H, Hannonen P, et al. Clinical effectiveness of CT-P13 (infliximab biosimilar) used as a switch from Remicade (infliximab) in patients with established rheumatic disease. Report of clinical experience based on prospective observational data. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15:1677–83.

Sheppard M, Hadavi S, Hayes F, Kent J, Dasgupta B. AB0322 Preliminary data on the introduction of the infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13) to a real world cohort of rheumatology patients [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1011.

Scherlinger M, Germain V, Labadie C, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 in real-life: the weight of patient acceptance. Jt Bone Spine. 2017;85:561–7.

Tweehuysen L, van den Bemt BJF, van Ingen IL, et al. Subjective complaints as the main reason for biosimilar discontinuation after open-label transition from reference infliximab to biosimilar infliximab. Arthritis Rheum. 2018;70:60–8.

Valido A, Silva-Dinis J, Saavedra MJ, Bernardo N, Fonseca JE. AB1231 Efficacy and cost analysis of a systematic switch from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 of all patients with inflammatory arthritis from a single centre [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:A1712.

Yazici Y, Xie L, Ogbomo A, et al. SAT0175 A descriptive analysis of real-world treatment patterns in a Turkish rheumatology population that continued innovator infliximab (Remicade) therapy or switched to biosimilar infliximab [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2903–6.

Yazici Y, Xie L, Ogbomo A, et al. Analysis of real-world treatment patterns in a matched rheumatology population that continued innovator infliximab therapy or switched to biosimilar infliximab. Biologics. 2018;12:127–34.

Binkhorst L, Sobels A, Stuyt R, Westerman EM, West RL. Switching to a infliximab biosimilar: short-term results of clinical monitoring in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:699–703.

Jung YS, Park DI, Kim YH, et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13, a biosimilar of infliximab, in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a retrospective multicenter study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1705–12.

Razanskaite V, Bettey M, Downey L, et al. Biosimilar infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease: outcomes of a managed switching programme. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:690–6.

Schmitz EMH, Boekema PJ, Straathof JWA, et al. Switching from infliximab innovator to biosimilar in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a 12-month multicentre observational prospective cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:356–63.

Avouac J, Molto A, Abitbol V, et al. Systematic switch from innovator infliximab to biosimilar infliximab in inflammatory chronic diseases in daily clinical practice: the experience of Cochin University Hospital, Paris, France. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;47:741–8.

Strand V, Cohen S, Crawford B, Smolen JS, Scott DL, Leflunomide Investigators Groups. Patient-reported outcomes better discriminate active treatment from placebo in randomized controlled trials in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2004;43:640–7.

Khraishi M, Foley J, Stein E. FRI0184 Increasing treatment time on infliximab is predictive of incrementally better long-term retention in stable infliximab rheumatology patients in Canada [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:496.

Khraishi M, Ivanovic J, Zhang Y, et al. Long-term etanercept retention patterns and factors associated with treatment discontinuation: a retrospective cohort study using Canadian claims-level data. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37:2351–60.

Souto A, Maneiro JR, Gomez-Reino JJ. Rate of discontinuation and drug survival of biologic therapies in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of drug registries and health care databases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:523–34.

Reiland J-B, Freischem B, Roediger A. What pricing and reimbursement policies to use for off-patent biologicals in Europe?—results from the second EBE biological medicines policy survey. GaBI J. 2017;6:1–18.

Kristensen LE, Alten R, Puig L, et al. Non-pharmacological effects in switching medication: the nocebo effect in switching from originator to biosimilar agent. Biodrugs. 2018;32:397–404.

Odinet JS, Day CE, Cruz JL, Heindel GA. The bosimilar nocebo effect? a systematic review of double-blinded versus open-label studies. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24:952–9.

Rezk MF, Pieper B. To See or NOsee: the debate on the nocebo effect and optimizing the use of biosimilars. Adv Ther. 2018;35:749–53.

Frantzen L, Cohen JD, Trope S, et al. Patients’ information and perspectives on biosimilars in rheumatology: a French nation-wide survey. Jt Bone Spine. 2019;86:491–6.

Schmitz EMH, Benoy-De Keuster S, Meier AJL, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) as a tool in the switch from infliximab innovator to biosimilar in rheumatic patients: results of a 12-month observational prospective cohort study. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:2129–34.

Goll GL, Haavardsholm EA, Kvien TK. The confidence of rheumatologists about switching to biosimilars for their patients. Jt Bone Spine. 2018;85:507–9.

Lee JF, Litten JB, Grampp G. Comparability and biosimilarity: considerations for the healthcare provider. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:1053–8.

Hassett B, Scheinberg M, Castañeda-Hernández G, et al. Variability of intended copies for etanercept (Enbrel®): data on multiple batches of seven products. MAbs. 2018;10:166–76.

Camacho LH, Frost CP, Abella E, Morrow PK, Whittaker S. Biosimilars 101: considerations for US oncologists in clinical practice. Cancer Med. 2014;3:889–99.

Emery P, Weinblatt M, Smolen JS, et al. THU0184 Impact of immunogenicity on clinical efficacy and administration related reaction in TNF inhibitors: a pooled-analysis from three biosimilar studies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:A310.

Tebbey PW, Declerck PJ. Importance of manufacturing consistency of the glycosylated monoclonal antibody adalimumab (Humira®) and potential impact on the clinical use of biosimilars. GaBI J. 2016;5:70–3.

Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Benhar I, et al. Cross-immunogenicity: antibodies to infliximab in Remicade-treated patients with IBD similarly recognise the biosimilar Remsima. Gut. 2016;65:1132–8.

Ruiz-Argüello MB, Maguregui A, Ruiz Del Agua A, et al. Antibodies to infliximab in Remicade-treated rheumatic patients show identical reactivity towards biosimilars. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1693–6.

Reinisch W, Jahnsen J, Schreiber S, et al. Evaluation of the cross-reactivity of antidrug antibodies to CT-P13 and infliximab reference product (Remicade): an analysis using immunoassays tagged with both agents. Biodrugs. 2017;31:223–37.

Gils A, Van Stappen T, Dreesen E, Storme R, Vermeire S, Declerck PJ. Harmonization of infliximab and anti-infliximab assays facilitates the comparison between originators and biosimilars in clinical samples. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:969–75.

US Department of Health and Human Services. US Food and Drug Administration. Silver Spring: Considerations in demonstrating interchangeability with a reference product guidance for industry; 2019.

Schaeverbeke T, Pham T, Richez C, Wendling D. Biosimilars: an opportunity. Position statement of the French Rheumatology Society (SFR) and Inflammatory Rheumatic Disease Club (CRI). Jt Bone Spine. 2018;85:399–402.

Teeple A, Ellis LA, Huff L, et al. Physician attitudes about non-medical switching to biosimilars: results from an online physician survey in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35:611–7.

Glintborg B, Sørensen IJ, Loft AG, et al. Clinical outcomes from a nationwide non-medical switch from originator to biosimilar etanercept in patients with inflammatory arthritis after 5 months follow-up. Results from the DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:553.

Acknowledgements

Funding

AbbVie (North Chicago, IL, USA) funded development of this manuscript, including the journal’s Rapid Service Fees. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing Assistance

Maria Hovenden, PhD, and Morgan C. Hill, PhD, of Complete Publication Solutions, LLC (North Wales, PA, USA), provided medical writing and editorial support to the authors in the development of this manuscript, which was funded by AbbVie (North Chicago, IL, USA).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

The authors were involved in developing the content, writing, and critically reviewing the manuscript, and approved the final version. AbbVie provided a courtesy medical review; however, all decisions regarding content were made by the authors.

Disclosures

Roy Fleischmann has received consulting fees and/or performed clinical studies for AbbVie, Acea, Amgen, AstraZeneca, BMS, Celltrion, GSK, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Samsung, Samumed, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and UCB. Roy Fleischmann is also the Editor-in-Chief of this journal. Vipul Jairath has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Ferring, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Takeda, Topivert, and Robarts Clinical Trials, and has received speakers fees from AbbVie, Ferring, Janssen, Pfizer, Shire, and Takeda. Eduardo Mysler has received speakers fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, Pfizer, and Roche, and research grants from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chemo, Gemma, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, MedImmune, Pfizer, and Roche. Dave Nicholls has served on advisory boards for AbbVie and has clinical trial agreements with AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and UCB. Paul Declerck participated in advisory board meetings for AbbVie, Amgen, Hospira, and Samsung Bioepis and is on the speakers’ bureau of AbbVie, Celltrion, Hospira, Merck Serono, and Roche.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11353061.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Fleischmann, R., Jairath, V., Mysler, E. et al. Nonmedical Switching From Originators to Biosimilars: Does the Nocebo Effect Explain Treatment Failures and Adverse Events in Rheumatology and Gastroenterology?. Rheumatol Ther 7, 35–64 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-019-00190-7

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-019-00190-7