Abstract

The Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP) has been used as a measure of implicit cognition and has been used to analyze the dynamics of arbitrarily applicable relational responding. The current study uses the IRAP for the latter purpose. Specifically, the current research focuses on a pattern of responding observed in a previously published IRAP study that was difficult to explain using existing conceptual analyses. The pattern is referred to as the single-trial-type dominance effect because one of the IRAP trial types produces an effect that is significantly larger than that of the other three. Based on a post hoc explanation provided in a previously published article, the first experiment in the current series explored the impact of prior experimental experience on the single-trial-type dominance effect. The results indicated that the effect was larger for participants who reported high levels of experimental experience (M = 32.3 previous experiments) versus those who did not (M = 2.5 previous experiments). In the second experiment, participants were required to read out loud the stimuli presented on each trial and the response option they chose. The effect of experimental experience was absent, but the single-trial-type dominance effect remained. In the third experiment, a different set of stimuli than those used in the first two experiments was used in the IRAP, and a significant single-trial-type dominance effect was no longer observed. The results obtained from the three experiments led inductively to the development of a new model of the variables involved in producing IRAP effects—the differential arbitrarily applicable relational responding effects (DAARRE) model—which is presented in the General Discussion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

All stimuli used in the current IRAP were presented to participants in Dutch. For the purposes of this article, the English translations will be used. The original Dutch versions of all on-screen instructions and a full list of stimuli are available from the first author on request.

As noted in the Introduction, the term orienting is used to denote a type of Cfunc property. We did consider using alternative terms, such as salience, but we felt that orienting evokes the involvement of a response function for a stimulus. In contrast, salience seems to imply that a stimulus may “stand out” independently of a behavioral history that is attached to it.

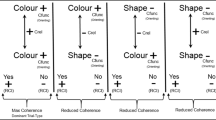

Note that coherence refers here to the functional overlap of the Cfunc properties (in this case, the orienting functions for the label and target stimuli and the yes response option) that have been established by the participant’s pre-experimental history of relational responding with regard to those specific stimuli.

The mean effect size and standard error for each trial type for each group are available upon request.

Although perhaps a minor procedural issue, it may be worth noting that the instructions to focus on forks or spoons in Experiment 3 were presented on sheets of paper that participants were asked to physically flip over between blocks of trials. In the study reported by Finn et al. (2016), which did show an effect for different types of instructions on IRAP performances, these were presented on the computer screen between blocks, which may have enhanced their impact.

Although the DAARRE model highlights three variables that may interact to increase or decrease levels of coherence (i.e., the Crel, Cfunc, and RCI properties of the stimuli), we are not proposing three functionally distinct types or classes of coherence. Coherence, as a concept in RFT, may be interpreted as the extent to which a current pattern of arbitrarily applicable relational responding (AARRing) is consistent (i.e., coherent) with the behavioral history that gave rise to that AARRing. Critically, the level of coherence involved in a particular pattern of AARRing may be attributable to multiple interactive variables, but this does not imply a different type of coherence for every interactive pattern that may be identified. Coherence thus remains a unitary concept within the DAARRE model as currently expressed.

References

Barnes-Holmes, D., Barnes-Holmes, Y., Stewart, I., & Boles, S. (2010a). A sketch of the implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) and the relational elaboration and coherence (REC) model. The Psychological Record, 60, 527–542.

Barnes-Holmes, D., Murphy, A., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Stewart, I. (2010b). The implicit relational assessment procedure: Exploring the impact of private versus public contexts and the response latency criterion on pro-white and anti-black stereotyping among white Irish individuals. The Psychological Record, 60, 57–66.

Barnes-Holmes, D., Finn, M., McEnteggart, C., & Barnes-Holmes, Y. (2017). Derived stimulus relations and their role in a behavior-analytic account of human language and cognition. The Behavior Analyst. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-017-0124-7.

Carpenter, K. M., Martinez, D., Vadhan, N. P., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Nunes, E. V. (2012). Measures of attentional bias and relational responding are associated with behavioral treatment outcome for cocaine dependence. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38, 146–154. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2011.643986.

Dodds, P. S., Clark, E. M., Desu, S., Frank, M. R., Reagan, A. J., Williams, J. R., & Danforth, C. M. (2015). Human language reveals a universal positivity bias. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(8), 2389–2394. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1411678112.

Dymond, S., & Roche, B. (2013). Advances in relational frame theory: Research and application. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Finn, M., Barnes-Holmes, D., Hussey, I., & Graddy, J. (2016). Exploring the behavioral dynamics of the implicit relational assessment procedure: The impact of three types of introductory rules. The Psychological Record, 66, 309–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-016-0173-4.

Hayes, S. C., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Roche, B. (2001). Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic.

Hughes, S., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2011). On the formation and persistence of implicit attitudes: New evidence from the implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP). The Psychological Record, 61, 391–410.

Hughes, S., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2016a). Relational frame theory: The basic account. In R. Zettle, S. C. Hayes, D. Barnes-Holmes, & A. Biglan (Eds.), Wiley handbook of contextual behavioral science (pp. 176–232). Cambridge, England: Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118489857.ch9.

Hughes, S., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2016b). Relational frame theory: Implications for the study of human language and cognition. In R. Zettle, S. C. Hayes, D. Barnes-Holmes, & A. Biglan (Eds.), Wiley handbook of contextual behavioral science (pp. 233–291). Cambridge, England: Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118489857.ch10.

Keuleers, E., Diependaele, K., & Brysbaert, M. (2010). Practice effects in large-scale visual word recognition studies: A lexical decision study on 14,000 Dutch mono- and disyllabic words and nonwords. Frontiers in Psychology, 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00174.

Leech, A., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Madden, L. (2016). The implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) as a measure of spider fear, avoidance, and approach. The Psychological Record, 66, 337–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-016-0176-1.

Maloney, E., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2016). Exploring the behavioral dynamics of the implicit relational assessment procedure: The role of relational contextual cues versus relational coherence indicators as response options. The Psychological Record, 66, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-016-0180-5.

Nicholson, E., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2012). The implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) as a measure of spider fear. The Psychological Record, 62, 263–278.

Sidman, M. (1971). Reading and auditory-visual equivalences. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 14, 5–13.

Sidman, M. (1994). Equivalence relations and behavior: A research story. Boston: Authors Cooperative.

Funding

The research reported herein was supported by a FWO Type I Odysseus grant (2015–2020) awarded to Dermot Barnes-Holmes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human Participants and Animal Studies

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Finn, M., Barnes-Holmes, D. & McEnteggart, C. Exploring the Single-Trial-Type-Dominance-Effect in the IRAP: Developing a Differential Arbitrarily Applicable Relational Responding Effects (DAARRE) Model. Psychol Rec 68, 11–25 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-017-0262-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-017-0262-z