Summary

Background

In a world with rapidly increasing urbanization and loss of closeness to nature and biodiversity, the question arises to what extent our environment influences the health of people and animals. Moreover, in recent decades, the prevalence of respiratory diseases such as asthma and allergies has risen sharply. In this context, a direct link between the health of people and their environment seems plausible.

Results

Recent studies indicate that spending time in and being in contact with natural environments such as green spaces and associated soils is highly relevant to the health of people and companion animals. Green spaces in the environment of homes and schools of children and adults could contribute to the reduction of asthma and allergies. Especially the number and the structure of green spaces seems to be crucial. Home gardens and regular contact with animals can also reduce the risk of asthmatic and allergic diseases. In contrast, the increasing number of gray areas (roads, highways, construction sites, etc.) is likely to increase the risk of asthma and allergies. In the case of blue areas (rivers, lakes, sea), no correlation with atopic diseases has been found so far.

Conclusion

Biodiverse green spaces, especially forests and meadows, may offer some protection against asthma and allergies. Contact with soil and ground also seems important for the diverse skin microbiome, especially in childhood, and thus presumably beneficial for the immune system. Therefore, people and man’s best friend, the dog, should spend sufficient time in green, biodiverse environments, despite—or perhaps because—of rapid urbanization. People should also actively create such biodiverse surroundings in their closer living environment. On a broader level, in the spirit of the One Health concept, those responsible for city planning and transportation must take these connections into account.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The One Health concept

One Health is a concept that takes a holistic view on the health of people, animals, plants, and our environment. In this concept, problems are dealt with in an interdisciplinary way and by experts from many different fields and from different perspectives. It is also recognized that human health is closely related to a healthy state of the environment, vegetation, and animals. Typical problems, which also need to be addressed in a more interdisciplinary and holistic way, are asthma and allergy. The effects of changes in biodiversity, air and water pollution, emissions, global warming, urbanization, altered microbiome of people/animals/environment, application and remnants of medical substances, reduced exercise, processing of our food, nature of our living environment, and many more factors have to be considered. These factors can influence the development of allergy and asthma and must be included in the One Health concept when investigating causes, prevention, and, if necessary, treatment [1].

Factors influencing the development of asthma and allergy

The prevalence of asthma and allergies has risen sharply in recent decades. These diseases can represent a considerable restriction on the quality of life for those affected. The probability of developing allergy and/or asthma depends on endogenous as well as exogenous factors.

Genetics has a significant influence on both asthma and allergy, as the family history of these diseases is often reflected in the child [2]. It is estimated that the heritability of asthma ranges from 35 to 95% and of allergic rhinitis from 33 to 91% [3]. Thus, the probability that a child will develop asthma increases three-fold with one parent and six-fold with two parents being affected by asthma [4]. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that genetic factors alone have caused the rapid increase in diseases over the last few decades, and it is becoming increasingly clear that there must be an interaction between genes and the environment of the affected individuals [5, 6]. In this respect, cigarette smoke (passive and active), air pollution, growing up on a farm, contact with animals, but also diet, among others, may play a role [7]. Socioeconomic status, described by income, education, or occupation, also has a decisive influence because asthma and allergies can be very high in regions with poorer socioeconomic conditions [8, 9]. When genetic and socioeconomic factors have been included in the studies discussed below, they have been mentioned in Table 1.

Due to the ever-growing urbanization with the sealing of soil areas of our living, working, and school environment, human beings are losing contact with biodiversity and proximity to nature and wildlife [10]. This fact has negative consequences: people who live in urban areas with fewer green spaces are more likely to be affected by various immunological, metabolic, and mental diseases than those who live in rural areas [10, 11]. The question now arises, which and how many areas in our living environment can contribute to the protection against asthma and allergic diseases.

Green spaces: do they help protect against allergy and asthma?

Exposure to, and interaction with, green spaces and biologically diverse environments are associated with numerous benefits for physical and mental health [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Several studies show that green spaces influence the incidence of asthma and allergies; however, some of these provide mixed results (Table 1; [18]). The reason for this could be the heterogeneity of the settings in the studies conducted, as it probably depends on how (which measurement parameters), where (geographic location), and when (season, life stage of the subjects) the green spaces were assessed, and on other factors that may influence disease incidence but may not have been equally considered (e.g., pollen season, proximity to airports, highways, or farms) [2]. In addition to the size of the area, the structure as well as the characteristics of the green spaces seem to be of importance for asthma and allergy development [18,19,20].

Green spaces can represent both benefits and drawbacks for people and wildlife. One advantage is improved air quality, as increased green spaces of all types filter harmful particles and substances such as CO2 and NO2 from the air. Thus, green spaces can reduce lung exposure to harmful particles, thereby reducing asthma and allergy prevalence [18, 20].

As mentioned above, genetics also play an important role in the development of asthma. The influence of green space simultaneously with the genetic aspect was the focus of a research team from Toronto [18]. This city is home to a high number of ethnic populations and at the same time has a substantial variety of vegetation. According to the authors, the results are therefore suitable as a reference for affected ethnic populations in other countries. Green areas were measured by the ratio of vegetation components. For this, trees were surveyed separately from shrubs and grasses, and a ratio of these two groups was created. Using this ratio (“ratio of trees to shrubs–grass”), it was observed that a high ratio has a reducing effect on the incidence of asthma in 0–19-year olds. Furthermore, it was found that this effect can be enhanced by high tree diversity. A score for the density and diversity of street trees in the neighborhood was used as a parameter for tree diversity. However, such a positive effect could no longer be found for people over 20 years [18]. This discrepancy has been observed in several studies, and it was found that the influences of different factors can differ significantly among age groups. Even if the environment observed in the study is the same, it may still show different results on the incidence of asthma, as it seems that the effects may differ in different age groups and genders [21].

When comparing indoor with outdoor environments of 6–12-year olds in Budapest, children who lived in the suburbs had less asthma than those who lived centrally in the capital city [7]. The survey was conducted in 21 schools with questionnaires distributed to the children’s parents to determine whether they had asthma or had already been diagnosed by a doctor, and to assess the children’s symptoms (wheezing, breathing noises), living environment, lifestyle, and diet. This study showed that air pollution from heavy automobile traffic and areas with grasses and weeds were associated with a higher risk of asthma. Indoors, smoking (both, contact during the first year of life and at the time of the survey between the ages of 6 and 12 years of age) and molds were identified to increase asthma, while having a pet rodent or a plant in the bedroom was associated with lower asthma risk. Children’s regular physical activity significantly reduced respiratory symptoms [7].

A study investigated the association between landscape characteristics and allergic symptoms in 8–12-year olds in Austria and Italy [2]. For this purpose, data of the Wipptal and the Unterinntal and their neighboring valleys were collected. These valleys are characterized by their rural environment, but are located close to the traffic-busy Brenner Pass. This unique environment, characterized by strong vegetation and biodiversity, coexists with a high level of exhaust gases. The evaluation of green and gray area indicators around the residential area (100, 500, and 1000 m) and the children’s school area (100 m) showed that the prevalence of asthma and rhinitis decreases with increasing green area. The prevalence of asthma also decreases when the children have a residential garden and spend more time outdoors. On the other hand, when there was a decrease in green space within a 500 m radius of the children’s residential area, the prevalence of asthma increased. A higher number of green spaces also correlates with lower NO2 exposure and, consequently, a lower prevalence of asthmatic symptoms [2].

However, many of the studies mentioned above have only looked at the effect of green space at a specific time in children’s lives. Observing the effect of green spaces on children for 10 years, it was described that those who had more green spaces in their living environment during their lifetime (500 m) were less likely to develop allergic sensitization [20]. The authors suggest that children are more encouraged to play in the fresh air in green areas and, thus, have more interaction with these areas and soils [20]. There seems to be a specific window of opportunity in childhood when it is important to spend much time in as diverse a natural environment as possible, with trees and green spaces, to provide some protection against asthma and allergies.

Contrary to all the studies that could show that green spaces have positive effects on health, some found a negative association. Green spaces produce pollen, which can trigger allergic symptoms [18, 22]. In combination with other factors such as air pollution, fungal spores, or endotoxins, these can result in respiratory diseases. In one study, asthma medication sales were compared with three different types of green spaces (forest, grassland, and home garden) in the residential environment [23]. As one of the strengths of this study, the effects of the different types of green spaces were observed separately for gender and two different age groups (6–12 years and 13–18 years). In contrast to the positive effects described above, it was shown here that proximity to large areas of grasses or pastures could have a detrimental effect on children’s respiratory health and associated medication use. It was found that home gardens can also adversely affect children’s respiratory health, as in this case children are exposed to a variety of pollens and molds. In the group of 13- to 18-year-old girls, a small negative association was found between asthma medication sales and forest areas [23]. A meta-analysis of nine studies showed that a 10% increase in green space was significantly associated with a 5.9–13% increase in wheezing, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, but not eczema [24].

However, not only the green spaces themselves but also the associated soil contributes to the resulting effects. In general, sufficient contact with a natural environment is important because this contact enriches the human microbiome, which may improve immune balance, potentially protecting against allergies and inflammatory diseases (biodiversity hypothesis) [25, 26]. With the decrease of green areas, contact with soil and earth is disappearing progressively, and with it the influence on our microbiome. The influence of soil has been researched by modifying soils in kindergartens, which were enriched with turf and forest soil [27]. Furthermore, boxes for planting were provided to the children to enable active handling and contact with soil. One of the changes that could be shown over the observation period of 2 years was an enrichment of the soil microbiome with the genus Mycobacteria, which in the literature are said to have anti-inflammatory properties [28]. Very few to no mycobacteria were detected in the soils of standard nurseries without intervention. The authors speculate that the higher proportion of Mycobacteria in the soils may benefit children’s immune regulation, but further studies are needed. The microbiome in skin and saliva samples of the children showed more Gammaproteobacteria after one year of observation. Gammaproteobacteria were also found to increase after 2 years in the soil of the kindergartens with modification, but not in the standard kindergartens. This result also correlates with a higher diversity of this particular class of bacteria in the children’s skin and saliva samples. Higher numbers of Gammaproteobacteria in the soil and the skin microbiome have been associated with ideal immune modulation and already in the past with reduced risk of atopy and allergies [29, 30]. In parallel, fewer Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Streptococcus sp. and Veillonella sp. were found in the samples of children with modified soils compared to the control nurseries. These strains have been consistently associated with childhood asthma [27]. Therefore, by enriching the outdoor environment and soils in kindergartens, there is an opportunity to positively impact the microbiome and even reduce potential pathogens in the environment.

Not only green spaces and the respective soil but also the specific plant species growing in them are of interest for the development of asthma and allergy. A study from Portugal compared how the number of green spaces (normalized difference vegetation index, NDVI) and the number of plant species growing in them (species richness index, SRI) affected children [31]. Genetic as well as socioeconomic factors were also included in the statistical analysis of the study. Individuals who had physician-diagnosed allergy, rhinitis, or eczema were considered to have an allergic disease. The same was true for asthma. Those children who lived in areas with a high number of different plant species in the green areas (100 m around the residential area) had a significantly higher risk of suffering from allergic sensitization than children from regions with smaller species diversity: at the age of 4 years, the risk increased on average two-fold and at the age of 7 years even 2.4-fold. The authors explain this result by the fact that a higher number of species also brings a greater amount of plant-associated aeroallergens and consequently more symptoms for those affected. However, when only the “size of green space” factor was considered, this study was also able to show that children born in neighborhoods with a high proportion of green space (100 m around residential areas) had a lower risk of suffering from asthma at the age of 7 years and a lower prevalence of allergic rhinitis than children growing up in neighborhoods with little green space [31].

A special case for a protective environment against asthma and allergies for human beings and animals is provided by farms that induce the so-called farm effect. Here, not only the direct contact to cattle and the consumption of raw milk [32] but also the dust of the barn up to a distance of 300 m around the barn seems to be effective [33]. Our research group was able to show that an effective component in barn dust and ambient air—in addition to the good microbes and their components—is the milk protein beta-lactoglobulin (BLG). BLG is a carrier protein and, together with its ligands (vitamins, iron-siderophores, zinc), can positively modulate the immune system [34,35,36,37].

Gray areas: Does gray make us sick?

In addition to green spaces, increasing gray areas, such as larger cities and more roads or highways, are also of interest in allergy and asthma research (Table 1). Evidence is mounting that higher levels of gray areas, such as asphalt, correlate with allergies and respiratory health. A Finnish study was able to show that asphalt use increased ten-fold over three decades (1960–1990). A parallel and similar increase was found in the same paper for asthma prevalence in conscripts. This increased from 0.3% (1966) to 2.6% (1995) [38]. To measure the influence of gray areas near where children live (300 m), the CORINE (“Coordination of Information on the Environment”) program was used in a study [39]. Industrial, commercial, and transportation units were included, as well as mines, landfills, and construction sites. Furthermore, birth cohorts from two different biogeographical regions in Spain were compared. It was found that more gray areas around the residential area increase the risk of wheezing as well as bronchitis in children [39]. Also, in a study for adults (15–84 years), the CORINE program was used to measure the different land cover types around the residential area (1000 m) of the study participants [40]. The mean gray area percentage within a 1000 m radius of the study participants’ residential area was 46.52%. About one-third of the probands (32.8%) lived in areas with a gray area percentage of 31–40%, and 17.1% lived in areas with even 81–90% gray area percentage. Individuals with biomarkers for allergic diseases as well as individuals with serum antibodies against benzo(a)pyrene-diol-epoxide (BPDE) DNA adducts (as markers for exposure to environmental carcinogens as well as DNA damage) were found to have the highest levels of gray area exposure. Furthermore, a significantly higher probability was found for a positive skin prick test (SPT), polysensitization, rhinitis as well as only asthma or allergic rhinitis (without SPT positivity). A 10% increase in individual exposure to gray areas was associated with a higher incidence of SPT positivity, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. Thus, this study could describe a possible negative effect of gray areas [40]. In the study mentioned above, which investigated rural valleys but had the traffic-busy Brenner Pass nearby, it could be shown that a higher density of gray areas leads to an increase in asthma symptoms [2]. This effect is probably due to exhaust fumes from cars and the lower amount of filtering green areas. These results are not surprising since air pollution is a known asthma-amplifying factor. Since the number of studies on gray areas and asthma/allergy is very small, further studies need to clarify a direct causal effect.

Blue areas: Can water be helpful?

Comparing green areas and water areas such as lakes and rivers (Table 1), it was found that there was no significant association between water areas close to the residential area (500 m) and allergic sensitization in children after an observation period of 10 years [20]. A European study of 3‑ to 14-year-olds also failed to find a correlation between blue areas (bodies of water, coastal lagoons, estuaries, and the sea) in the living environment and allergic symptoms [24]. However, to be able to make an accurate statement about the effects of blue areas on allergy and asthma, further studies are necessary.

Are our pets also affected?

Our pets can also develop asthma and allergies [41,42,43]. A highly prevalent allergic skin disease in dogs is canine allergic dermatitis (CAD). It affects approximately 10–15% of the canine population and is a genetically predisposed allergic skin disease with itchy and inflamed skin areas. Since the number of cases of CAD has increased sharply in recent decades, it can be assumed that, as in humans, environmental factors may also play an important role ([44]; Table 2). Accordingly, dogs living in a city suffer more often from CAD than those living in rural areas. Regular walks with the dog in the forest seem to be particularly effective. The coexistence of the dog with other dogs or cats protects likewise [44]. A similar observation is made in humans, where a higher number of family members and living with pets is protective [45].

It has also been shown that people have different contact with green spaces and that those with pets, such as dogs, spend more time in them than others [46]. Therefore, it is not possible to individually assess the sole effect of different types of land cover, such as green spaces, from the numerous other factors that may affect asthma as well as allergy in owners and dogs.

It is very exciting that dogs and their owners who live in the same environment and have the same lifestyle show the same allergy prevalence: They are often healthy or show allergic symptoms at the same time. Of tested dog–owner pairs who share their living environment and lifestyle, 31% show sensitization to aeroallergens [47]. Another observation shows that a sensitized owner was more likely to have a dog that was sensitized than to have a healthy dog. There is a high probability that this effect is due to common underlying environmental and lifestyle factors [48]. To confirm this, the different microbial compositions of the environment of holders and dogs and their effects on the skin and gut microbiome were investigated. By analyzing skin and fecal samples from dog–owner pairs, it was shown that the gut microbiome is clearly different while the skin microbiome is similar and that the skin microbiome of dog–owner pairs is more similar than that of random dog–human pairs. A link between skin microbiome and lifestyle and living environment in dogs and holders was also found. Thus, a potentially important role of microbial exposure, lifestyle, and environment in the risk of allergy can be assumed. Since these results have been found in dogs and people, it is very likely that immune-related diseases may also have common environmental origins [47].

Discussion

The associations found in the as yet few studies show good correlations, but do not yet prove causality of the different areas in asthma and allergy development. Further studies—preferably prospective intervention studies—are needed. However, the existing studies support the hypothesis that environmental factors and surroundings, such as green spaces, among others, may support asthma and allergy prevention. Asthma and allergy are complex and multifactorial diseases, and the influence of green spaces can therefore only be one aspect among many.

In the sense of the One Health concept, it would be advantageous for necessary future studies to deal with questions in an interdisciplinary manner. It would also be desirable to include existing and new results in future urban planning in order to ensure better health for all. Therefore, the working group One Health of the EAACI (European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology) is dedicated to these topics and their practical implementation.

Conclusion

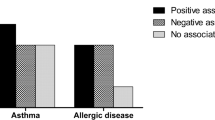

The work described shows correlations, but does not necessarily prove causality. Nevertheless, different results were found for gray, blue, and green areas: Gray areas could contribute to the development of asthma and allergies, blue areas have no influence as far as known so far, whereas trees, green areas, and soil with high biodiversity seem to protect against asthma and allergy development in people and animals (Fig. 1). In this sense, the way of cultivation and remodeling as well as the construction of the living environment as a holistic approach of the One Health concept [1] is an important contribution to the reduction of the “allergy pandemic” and these results should be incorporated into city planning in the future.

Effect of areas on the prevalence of asthma and allergies. Different areas probably influence the development of asthma and allergy in different ways. While gray areas (roads, highways, construction sites, etc.) could have a negative impact on the respiratory health of people and dogs, and no correlation has yet been found for blue areas (rivers, lakes, sea), green areas (parks, forests, grassland, and home garden) apparently offer a protective effect

Abbreviations

- BLG:

-

Beta-lactoglobulin

- BPDE-DNA:

-

Benzo(a)pyrene diol epoxide DNA adducts

- CAD:

-

Canine atopic dermatitis

- CORINE:

-

Coordination of information on the environment

- NDVI:

-

Normalized difference vegetation index

- RTSG:

-

Ratio of trees to shrubs–grass

- SPT:

-

Skin prick test

- SRI:

-

Species richness index

References

Pali-Schöll I, Roth-Walter F, Jensen-Jarolim E. One health in allergology: a concept that connects humans, animals, plants, and the environment. Allergy. 2021;76:2630–3.

Dzhambov AM, Lercher P, Rüdisser J, Browning MHEM, Markevych I. Allergic symptoms in association with naturalness, greenness, and greyness: a cross-sectional study in schoolchildren in the alps. Environ Res. 2021;198:110456.

Ober C, Yao T‑C. The genetics of asthma and allergic disease: a 21st century perspective: genetics of asthma and allergy. Immunol Rev. 2011;242:10–30.

Litonjua AA, Carey VJ, Weiss ST, Gold DR. Race, socioeconomic factors, and area of residence are associated with asthma prevalence. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999;28:394–401.

Pawankar R. Allergic diseases and asthma: a global public health concern and a call to action. World Allergy Organ J. 2014;7:12.

Murrison LB, Brandt EB, Myers JB, Hershey GKK. Environmental exposures and mechanisms in allergy and asthma development. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:1504–15.

Molnár D, Gálffy G, Horváth A, Tomisa G, Katona G, Hirschberg A, et al. Prevalence of asthma and its associating environmental factors among 6–12-year-old schoolchildren in a metropolitan environment—a cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:13403.

Mallol J, Crane J, von Mutius E, Odhiambo J, Keil U, Stewart A. The international study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC) phase three: a global synthesis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2013;41:73–85.

Mielck A, Reitmeir P, Wjst M. Severity of childhood asthma by socioeconomic status. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:388–93.

Markevych I, Schoierer J, Hartig T, Chudnovsky A, Hystad P, Dzhambov AM, et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ Res. 2017;158:301–17.

Rodriguez A, Brickley E, Rodrigues L, Normansell RA, Barreto M, Cooper PJ. Urbanisation and asthma in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review of the urban–rural differences in asthma prevalence. Thorax. 2019;74:1020–30.

Aerts R, Honnay O, Van Nieuwenhuyse A. Biodiversity and human health: mechanisms and evidence of the positive health effects of diversity in nature and green spaces. Br Med Bull. 2018;127:5–22.

Twohig-Bennett C, Jones A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ Res. 2018;166:628–37.

Islam MZ, Johnston J, Sly PD. Green space and early childhood development: a systematic review. Rev Environ Health. 2020;35:189–200.

Haahtela T, Alenius H, Lehtimäki J, Sinkkonen A, Fyhrquist N, Hyöty H, et al. Immunological resilience and biodiversity for prevention of allergic diseases and asthma. Allergy. 2021;76:3613–26.

Luo Y, Huang W, Liu X, Markevych I, Bloom MS, Zhao T, et al. Greenspace with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies up to 2020. Obes Rev. 2020;21:e13078.

Feng X, Flexeder C, Markevych I, Standl M, Heinrich J, Schikowski T, et al. Impact of residential green space on sleep quality and sufficiency in children and adolescents residing in Australia and Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4894.

Dong Y, Liu H, Zheng T. Association between green space structure and the prevalence of asthma: a case study of toronto. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:5852.

Kim D, Ahn Y. The contribution of neighborhood tree and greenspace to asthma emergency room visits: an application of advanced spatial data in Los Angeles county. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7):3487.

Paciência I, Moreira A, Moreira C, Cavaleiro RJ, Sokhatska O, Rama T, et al. Neighbourhood green and blue spaces and allergic sensitization in children: a longitudinal study based on repeated measures from the generation XXI cohort. Sci Total Environ. 2021;772:145394.

Trivedi M, Denton E. Asthma in children and adults—what are the differences and what can they tell us about asthma? Front Pediatr. 2019;7:256.

Jones NR, Agnew M, Banic I, Grossi CM, Colón-González FJ, Plavec D, et al. Ragweed pollen and allergic symptoms in children: results from a three-year longitudinal study. Sci Total Environ. 2019;683:240–8.

Aerts R, Dujardin S, Nemery B, Van Nieuwenhuyse A, Van Orshoven J, Aerts J‑M, et al. Residential green space and medication sales for childhood asthma: a longitudinal ecological study in Belgium. Environ Res. 2020;189:109914.

Parmes E, Pesce G, Sabel CE, Baldacci S, Bono R, Brescianini S, et al. Influence of residential land cover on childhood allergic and respiratory symptoms and diseases: evidence from 9 European cohorts. Environ Res. 2020;183:108953.

Haahtela T. A biodiversity hypothesis. Allergy. 2019;74:1445–56.

Prescott SL. Allergy as a sentinel measure of planetary health and biodiversity loss. Allergy. 2020;75:2358–60.

Roslund MI, Puhakka R, Nurminen N, Oikarinen S, Siter N, Grönroos M, et al. Long-term biodiversity intervention shapes health-associated commensal microbiota among urban day-care children. Environ Int. 2021;157:106811.

Xiao H, Zhang Q‑N, Sun Q‑X, Li L‑D, Xu S‑Y, Li C‑Q. Effects of mycobacterium vaccae aerosol inhalation on airway inflammation in asthma mouse model. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2021;34:374–82.

Fyhrquist N, Ruokolainen L, Suomalainen A, Lehtimäki S, Veckman V, Vendelin J, et al. Acinetobacter species in the skin microbiota protect against allergic sensitization and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1301–1309.e11.

Hanski I, von Hertzen L, Fyhrquist N, Koskinen K, Torppa K, Laatikainen T, et al. Environmental biodiversity, human microbiota, and allergy are interrelated. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8334–9.

Cavaleiro Rufo J, Paciência I, Hoffimann E, Moreira A, Barros H, Ribeiro AI. The neighbourhood natural environment is associated with asthma in children: a birth cohort study. Allergy. 2021;76:348–58.

Riedler J, Braun-Fahrländer C, Eder W, Schreuer M, Waser M, Maisch S, et al. Exposure to farming in early life and development of asthma and allergy: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2001;358:1129–33.

Borlée F, Yzermans CJ, Krop EJM, Maassen CBM, Schellevis FG, Heederik DJJ, et al. Residential proximity to livestock farms is associated with a lower prevalence of atopy. Occup Environ Med. 2018;75:453–60.

Afify SM, Pali-Schöll I, Hufnagl K, Hofstetter G, El-Bassuoni MA‑R, Roth-Walter F, et al. Bovine holo-beta-lactoglobulin cross-protects against pollen allergies in an innate manner in BALB/c mice: potential model for the farm effect. Front Immunol. 2021;12:611474.

Hufnagl K, Ghosh D, Wagner S, Fiocchi A, Dahdah L, Bianchini R, et al. Retinoic acid prevents immunogenicity of milk lipocalin Bos d 5 through binding to its immunodominant T‑cell epitope. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1598.

Roth-Walter F, Afify SM, Pacios LF, Blokhuis BR, Redegeld F, Regner A, et al. Cow’s milk protein β‑lactoglobulin confers resilience against allergy by targeting complexed iron into immune cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:321–334.e4.

Pali-Schöll I, Bianchini R, Afify SM, Hofstetter G, Winkler S, Ahlers S. Secretory protein beta-lactoglobulin in cattle stable dust may contribute to the allergy-protective farm effect. Clin Transl Allergy. 2022;12:e12125.

von Hertzen L, Haahtela T. Disconnection of man and the soil: reason for the asthma and atopy epidemic? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:334–44.

Tischer C, Gascon M, Fernández-Somoano A, Tardón A, Lertxundi Materola A, Ibarluzea J, et al. Urban green and grey space in relation to respiratory health in children. Eur Respir J. 2017;49:1502112.

Maio S, Baldacci S, Tagliaferro S, Angino A, Parmes E, Pärkkä J, et al. Urban grey spaces are associated with increased allergy in the general population. Environ Res. 2022; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.112428.

Pali-Schöll I, Blank S, Verhoeckx K, Mueller RS, Janda J, Marti E, et al. Comparing insect hypersensitivity induced by bite, sting, inhalation or ingestion in human beings and animals. Allergy. 2019;74:874–87.

Pali-Schöll I, De Lucia M, Jackson H, Janda J, Mueller RS, Jensen-Jarolim E. Comparing immediate-type food allergy in humans and companion animals—revealing unmet needs. Allergy. 2017;72:1643–56.

Mueller RS, Janda J, Jensen-Jarolim E, Rhyner C, Marti E. Allergens in veterinary medicine. Allergy. 2016;71:27–35.

Meury S, Molitor V, Doherr MG, Roosje P, Leeb T, Hobi S, et al. Role of the environment in the development of canine atopic dermatitis in labrador and golden retrievers: canine atopic dermatitis and environment. Vet Dermatol. 2011;22:327–34.

Hesselmar B, Hicke-Roberts A, Lundell A‑C, Adlerberth I, Rudin A, Saalman R, et al. Pet-keeping in early life reduces the risk of allergy in a dose-dependent fashion. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e208472.

Koohsari MJ, Nakaya T, McCormack GR, Shibata A, Ishii K, Yasunaga A, et al. Dog-walking in dense compact areas: the role of neighbourhood built environment. Health Place. 2020;61:102242.

Lehtimäki J, Sinkko H, Hielm-Björkman A, Laatikainen T, Ruokolainen L, Lohi H. Simultaneous allergic traits in dogs and their owners are associated with living environment, lifestyle and microbial exposures. Sci Rep. 2020;10:21954.

Hakanen E, Lehtimäki J, Salmela E, Tiira K, Anturaniemi J, Hielm-Björkman A, et al. Urban environment predisposes dogs and their owners to allergic symptoms. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1585.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Hanna Mayerhofer for proofreading and for valuable comments on the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

K. Zednik and I. Pali-Schöll declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zednik, K., Pali-Schöll, I. One Health: areas in the living environment of people and animals and their effects on allergy and asthma. Allergo J Int 31, 103–113 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-022-00210-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-022-00210-z