Abstract

Background

Studies have shown increased anxiety, depression, and stress levels among different populations during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. However, the impact of the pandemic on the mental health of dialysis patients remains unknown. The aim of this study was to investigate the mental health of dialysis patients during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the period preceding the pandemic.

Methods

Data originate from the ongoing multicentre observational Dutch nOcturnal and hoME dialysis Study To Improve Clinical Outcomes (DOMESTICO). Patients who filled in a health-related quality of life (HRQoL) questionnaire during the pandemic and six to three months prior were included. The mean difference in Mental Component Summary (MCS) score of the Short Form 12 (SF-12) was analysed with multilevel linear regression. A McNemar test was used to compare presence of mental health-related symptoms during and prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

A total of 177 patients were included. The mean MCS score prior to COVID-19 was 48.08 ± 10.15, and 49.00 ± 10.04 during the COVID-19 pandemic. The adjusted mean MCS score was 0.93 point (95% CI − 0.57 to 2.42) higher during the COVID-19 pandemic than during the period prior to the pandemic. Furthermore, no difference in the presence of the following mental health-related symptoms was found during the COVID-19 pandemic: feeling anxious, feeling sad, worrying, feeling nervous, trouble falling asleep, and trouble staying asleep.

Conclusions

The mental health of dialysis patients appears to be unaffected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Dialysis patients may be better able to cope with the pandemic, since they have high resilience and are less impacted by social distancing measures.

Trial registration number

Netherlands Trial Register NL6519, date of registration: 22 August 2017.

Graphic abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak that started in China rapidly spread across the globe, with major consequences for health and healthcare systems. Currently, the estimated number of infections worldwide is 66 million and the estimated number of deaths is 1.5 million [1]. In the Netherlands, the first COVID-19 patient was diagnosed on February 27th, 2020 [2]. In response, the Dutch government announced drastic measures; they obliged social distancing including working from home and closing all educational institutions, restaurants, cultural and sporting facilities, to limit further spread of the virus.

The current COVID-19 outbreak has been shown to increase levels of anxiety, depression, and stress among the general population [3,4,5]. In patients with Alzheimer’s disease and immunodeficiency, COVID-19 also resulted in higher anxiety levels and a higher risk of developing depression [6, 7]. Moreover, patients with chronic conditions had an increased risk of developing sleeping disorders [8]. Patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) who are treated with dialysis have a higher risk of a severe clinical course of COVID-19 and worse outcome [9]. The knowledge that they have a higher risk of infection, can become more seriously ill and have a higher mortality risk might result in symptoms like feeling anxious, feeling sad, worrying, feeling nervous and sleeping problems. Moreover, the psychological well-being of dialysis patients may also be affected by fear among fellow patients and healthcare professionals. However, data regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of dialysis patients are lacking. The aim of this study was to investigate the mental health of dialysis patients during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the period preceding the pandemic.

Methods

Study population and design

To compare the mental health of dialysis patients prior to the COVID-19 pandemic with a period during the COVID-19 pandemic, data were used from the ongoing Dutch nOcturnal and hoME dialysis Study To Improve Clinical Outcomes (DOMESTICO, Netherlands Trial Register identifier: NL6519) [10]. In this nationwide, prospective, observational study the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of home dialysis, i.e. peritoneal dialysis and home haemodialysis, patients is compared with the HRQoL of in-centre haemodialysis patients. All adult patients that started chronic dialysis were potentially eligible and all included patients provided written informed consent. The first patient was recruited in December 2017 and the end of the inclusion period is expected in 2021.

For the present study, patients were included if they had completed a HRQoL questionnaire during the COVID-19 pandemic, defined as the period between February 27th and July 1st, 2020, and a questionnaire 6 months prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. When the questionnaire administered 6 months prior to the COVID-19 pandemic was not available, the questionnaire administered 3 months prior to the COVID-19 pandemic was used.

Outcome parameters

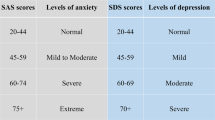

The primary outcome parameter was mental health, assessed with the Mental Component Summary (MCS) score of the 12-item Short Form (SF-12) health survey. The MCS was calculated using standard algorithms, meaning that a healthy individual scores 50 points on a scale of 0–100 with a standard deviation of 10 points [11, 12]. Higher scores of the MCS reflect better HRQoL [11]. The secondary outcome parameters were the Physical Component Summary (PCS) score of the SF-12, and the presence and severity of mental health-related symptoms assessed with the Dialysis Symptom Index (DSI) [11, 13]. These symptoms included feeling anxious, feeling sad, worrying, feeling nervous, trouble falling asleep, and trouble staying asleep. A 5-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘not at all bothersome’ to ‘very bothersome’, was used to evaluate the severity of these 6 symptoms [13].

Data collection

The following sociodemographic and clinical data were collected at study baseline: sex, age, primary kidney disease, living situation (alone, with a partner, or in a nursing home), level of education, work status, history of comorbidities, recent start, dialysis modality (in-centre haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or home haemodialysis), and acute start at dialysis initiation. Primary kidney disease was classified according to the codes of the ERA-EDTA. A higher level of education includes university colleges and university of applied sciences. Comorbidity was scored according to the Charlson comorbidity index [14]. Recent start of dialysis was defined as start of dialysis 6 months prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Acute start of dialysis was defined as an unplanned start of dialysis with no previous consultation of a nephrologist.

In addition, the questionnaires were reviewed to check whether participants had written comments related to COVID-19.

Statistical analysis

All normally distributed continuous variables are presented as mean with standard deviation (SD), non-normally distributed variables as median with interquartile range (IQR), and categorical variables as proportion.

Multilevel linear regression was used to assess the overall association between the COVID-19 pandemic and MCS or PCS score. The multilevel model was used to adjust for correlation of repeated observations within a patient. Both crude and adjusted analyses were performed. Adjusted models were corrected for sex, age, Charlson comorbidity index, higher education level, dialysis modality, and recent start of dialysis.

A McNemar test was used to compare the presence of mental health-related symptoms prior to the COVID-19 pandemic with the period during the COVID-19 pandemic. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the severity of mental health-related symptoms prior to the COVID-19 pandemic with the period during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the severity scores of the 6 mental health-related symptoms were added up to an overall symptom severity score ranging from 0 to 30, in which a severity score of 30 meant that in all mental health-related symptoms the maximum severity score was reported [13, 15].

Missing values of SF-12 items and confounders were imputed with standard multiple imputation techniques using 10 repetitions and predictive mean matching (SPSS) [16]. A difference of 3 points on the MCS and PCS was considered clinically relevant and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant [17, 18]. All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM) or STATA 14.

Results

A total of 177 patients were included, of whom 125 had filled in a questionnaire 6 months prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and 52 had filled in a questionnaire 3 months prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of patients (87%) had filled in their HRQoL questionnaires completely. Patient characteristics are depicted in Table 1. The majority (63%) was male, the mean age of the study population was 64.9 ± 11.5 years and 61% started dialysis 3–6 months prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Only 1% of the study population was infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The MCS score was 48.08 ± 10.15 prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and 49.00 ± 10.04 during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 1a). The mean MCS score was 0.91 point (95% CI − 0.59 to 2.41, p-value 0.2) higher during the COVID-19 pandemic than prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 2). Adjustment for multiple confounders did not change this result.

The PCS score was 35.92 ± 9.99 prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and 37.52 ± 10.38 during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 1b). The mean PCS score was 1.63 point (95% CI 0.28 to 2.99, p-value 0.02) higher during the COVID-19 pandemic than prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 2). Adjustment for multiple confounders did not change this result.

As depicted in Fig. 2, patients on dialysis reported frequently that they were feeling sad (33% vs 35%), were worrying (35% vs 36%), had trouble falling asleep (37% vs 39%) and had trouble staying asleep (53% vs 51%). For all mental health-related symptoms, there was no significant difference in presence prior to the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the period during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Also, no difference was found regarding the total number of mental health-related symptoms: 74% of patients reported at least 1 symptom prior to the COVID-19 pandemic compared to 72% of patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, while 7% of patients reported all 6 symptoms prior to the COVID-19 pandemic compared to 6% of patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The severity of mental health-related symptoms was not significantly higher during the COVID-19 pandemic (Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, the total symptom severity score (ranging from 0 to 30) did not differ between the two time periods (4 [IQR 0–8] prior to the pandemic vs 4 [IQR 0–9] during the COVID-19 pandemic).

Finally, a few patients wrote comments on the questionnaire concerning the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients commented that the COVID-19 pandemic had a huge impact on everyday life and that more help by informal caregivers was needed. For example, a patient wrote ‘this corona period also affects our daily life. Due to my health condition, we have tried to avoid all threats. The domestic help is no longer coming and grocery shopping has been done by our children.’ Another patient wrote ‘Daily life has changed quite a bit due to corona. I stay indoors as much as possible’. Few patients also noted that they felt isolated, ‘Loneliness because of corona. I am unable to receive visitors and all other activities have been discontinued.’

Discussion

This study showed that the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect the self-reported mental health of dialysis patients, as measured with HRQoL questionnaires. Dialysis patients did not report a higher burden or a higher severity of mental health-related symptoms such as feeling anxious, feeling sad, worrying, feeling nervous, trouble falling asleep, and trouble staying asleep.

A possible explanation for our findings could be that dialysis patients already suffer greatly from their kidney disease and treatment, which could limit the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Dialysis has a major impact on the mental health of dialysis patients resulting in a lower HRQoL than patients with other chronic illnesses such as malignancies [19, 20]. Mittal et al. [20] found that patients with kidney disease had a 2.68 point lower MCS score compared to the general population, whereas patients with malignancies had a 0.31 lower MCS score compared to the general population. In addition, dialysis patients have to deal with fluid restrictions, polypharmacy, and frequent hospital visits. As a result, dialysis patients have to adjust their everyday life for they encounter all these difficulties and adversities. As such, they have developed coping mechanisms in order to maintain satisfactory mental health. This ability to adapt is called resilience in literature and is often described as ‘a measure of successful stress-coping ability’ [21]. Resilience includes having a positive perception, accepting a burdensome situation, and being motivated to overcome various difficulties [22]. In a Spanish study, a higher level of resilience was associated with higher HRQoL scores [23]. The importance of resilience for both haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients to overcome the burden of dialysis has been emphasized in multiple studies [24,25,26]. In one of these studies the resilience of dialysis patients was quantified with a frequently used resilience scale. They found a score of 82.4 in dialysis patients, comparable to the general population (80.4) and reasonably higher than among patients visiting a general practitioner (71.8) [21, 24]. Dialysis patients may have a high level of resilience compared to primary care patients, as they have learned to adapt over time to bear the burden of dialysis and their disease in general, which could explain their ability to deal better with different stressors such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

The large amount of unemployed dialysis patients in our population may also explain why the COVID-19 pandemic did not seem to affect mental health. A study showed that people who are unemployed had higher mental distress in general, but did not experience an increase of mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic as assessed with the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (change score − 0.48 (95% CI − 1.55 to 0.60) [27]. Whereas people who are employed during the COVID-19 pandemic experienced an increase in mental distress compared to the period before COVID-19 (change score 0.63 (95% CI 0.20–1.06) [27, 28]. In our population only 16% was employed, which is consistent with clinical practice as many dialysis patients are unemployed.

The third possible explanation for our results could be that 75% of our study population received in-centre haemodialysis, which might diminish mental problems that could have developed as a result of the national social isolation. Support from fellow patients, nurses, and health care professionals can contribute to a reduced sense of loneliness. Moreover, dialysis patients usually participate less in everyday activities than age-matched healthy individuals or even kidney transplant patients due to the nature of the dialysis treatment [29]. The regular visits to the hospital for dialysis treatments consumes an important part of the patient’s time, with less time for social activities, work or travelling. Dialysis patients will be affected less by national policy measures such as social distancing since they experience fewer major changes in everyday life. In addition, in-centre haemodialysis patients might experience a sense of safety during their hospital visits that further limits the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health. In the Netherlands, many precautionary measures were taken at dialysis centres, such as screening for fever/complaints at entry for all patients, distance of 1.5 m whenever possible between people and wearing of face masks for dialysis patients, dialysis nurses and physicians early in the course of the pandemic. Also, dialysis patients that attended the hospital for haemodialysis sessions were able to obtain adequate information concerning COVID-19 directly from their health care professionals. In a Chinese study it was found that more information about the disease contributed to less anxiety levels [4].

It should be noted that some dialysis patients did express feelings of loneliness due to social isolation in the additional comments of the questionnaire. Because of their vulnerability they were being extra careful to protect themselves; informal caregivers took over many tasks for the patients so that they could avoid contact with others as much as possible. In a national survey among the general Dutch population, more than half of the participants indicated moderate or severe feelings of loneliness from April to June 2020. Nonetheless, they found that concerns among the general Dutch population began to subside around the end of March 2020 [30]. At this point the number of newly reported corona cases also began to decline. Compared to other countries in Europe including France, the United Kingdom and Italy, the number of newly reported COVID-19 patients and deaths was lower in the Netherlands, which could be a final explanation of the results in our study [31].

The results of our study are in line with a recent study in the United Kingdom, which showed that the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect the mental health of patients with chronic illnesses as assessed with a generic HRQoL questionnaire (change score in the GHQ-12 0.40 (95% CI − 0.30 to 1.09) [27]. Contradictory, an online survey among 1210 Chinese people found higher levels of stress, depression, and anxiety among those with a history of chronic illnesses [4]. Another study conducted in Northern Spain also showed higher levels of stress, depression, and anxiety among those with a history of chronic illnesses [5]. Unfortunately, none of all these studies specified the participants’ diseases, making a good comparison with our study population difficult. Also, in two studies no comparison with a historic control group or a pre-COVID-19 assessment of mental health was performed [4, 5].

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating whether the COVID-19 pandemic affects the mental health of dialysis patients. Strengths of this study include the use of validated self-reported HRQoL questionnaires and the use of an existing prospective and nationwide cohort of dialysis patients (DOMESTICO) for analysis. Moreover, the number of patients in our study would have been sufficient to detect a significant difference in SF-12 composite scores between time periods as small as 2.17, whereas a difference of 3 is defined clinically relevant in literature [17, 18]. We calculated in our sample size that a total of 123 patients was sufficient to detect a 3 point difference between time points (α = 0.05, β = 0.10). In our study, we had a 97% power to detect such a clinically relevant difference. A limitation of our study might be that the MCS score of the SF-12 questionnaire is not sensitive enough to detect differences over time in individuals, i.e. that the MCS score has limited responsiveness [32]. To overcome this issue, we also used the DSI which provides more detailed information about the mental health of the patients. Another limitation might be that the chosen period of the COVID-19 pandemic was too short to demonstrate an association with mental health. The COVID-19 virus is still spreading and its effect on the economy is currently unclear. Therefore, if the pandemic lasts longer, a negative impact on mental health may still be revealed.

In conclusion, the mental health of dialysis patients assessed with SF-12 and DSI appears to have been unaffected during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. This could be explained by higher resilience, more unemployment among dialysis patients, less impact of social distancing on the dialysis population, strict precautionary measures and perceived support from health care professionals, which may all contribute to better coping with the COVID-19 pandemic. However, a second peak of COVID-19 is expected and the economic burden of the pandemic has yet to be discovered. Therefore, it is important to continue paying attention to the concerns and needs of our dialysis population.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article are subject to an embargo of twelve months after completion of the DOMESTICO study. Once the embargo expires the data will be available upon reasonable request.

References

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) (2020) WHO. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 7 Dec 2020

Ontwikkeling COVID-19 in grafieken (2020) RIVM. https://www.rivm.nl/coronavirus-covid-19/grafieken. Accessed 1 Nov 2020

McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H et al (2020) Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA J Am Med Assoc 324:93–94

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X et al (2020) Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:1729

Ozamiz-etxebarria N, Dosil-santamaria M, Picaza-gorrochategui M et al (2020) Stress, anxiety, and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain Niveles de estrés, ansiedad y depresión en la primera fase del brote del COVID-19 en una muestra recogida en el norte de E. Cad Saude Publ 36:1–9

Beatriz Lara B, Carnes A, Dakterzada F et al (2020) Neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life in Spanish Alzheimer’s disease patients during COVID-19 lockdown. Eur J Neurol 25:1744–1747

Pulvirenti F, Cinetto F, Milito C et al (2020) Health-related quality of life in common variable immunodeficiency Italian patients switched to remote assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 8(6):1894-1899.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.04.003

Gualano MR, Lo Moro G, Voglino G et al (2020) Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:1–13

Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K et al (2020) Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 584:430–436

van Eck van der Sluijs A, Bonenkamp AA, Dekker FW et al (2019) Dutch nOcturnal and hoME dialysis study to improve clinical outcomes (DOMESTICO): rationale and design. BMC Nephrol 20:361. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-019-1526-4

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD (1996) A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 34:220–233

Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK et al (1998) Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. J Clin Epidemiol 51:1171–1178

Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM et al (2004) Development of a symptom assessment instrument for chronic hemodialysis patients: the dialysis symptom index. J Pain Symptom Manage 27:226–240

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL et al (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383

Abdel-Kader K, Unruh ML, Weisbord SD (2009) Symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in chronic and end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4:1057–1064

Eekhout I, De Vet HCW, Twisk JWR et al (2014) Missing data in a multi-item instrument were best handled by multiple imputation at the item score level. J Clin Epidemiol 67:335–342

Lacson E, Xu J, Lin SF et al (2010) A comparison of SF-36 and SF-12 composite scores and subsequent hospitalization and mortality risks in long-term dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5:252–260

Kosinski M (2007) User’s manual for the SF-12v2 health survey: with a supplement documenting the SF-12® health survey. In: Lincoln RI: Quality Metric Incorporated

van Sandwijk MS, Arashi DA, van de Hare FM et al (2019) Fatigue, anxiety, depression and quality of life in kidney transplant recipients, haemodialysis patients, patients with a haematological malignancy and healthy controls. Nephrol Dial Transplant 34:833–838

Mittal SK, Ahern L, Flaster E et al (2001) Self-assessed physical and mental function of haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 16:1387–1394

Connor KM, Davidson JRT (2003) Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety 18:76–82

Kim EY, Lee YN, Chang SO (2019) How do patients on hemodialysis perceive and overcome hemodialysis? Concept development of the resilience of patients on hemodialysis. Nephrol Nurs J 46(5):521–530

García-Martínez P, Temprado-Albalat MD, Ballester-Arnal R et al (2020) Predictive model of variables associated with health-related quality of life in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease receiving hemodialysis. Qual Life Res 29:1817–1827

Kukihara H, Yamawaki N, Ando M et al (2020) The mediating effect of resilience between family functioning and mental well-being in hemodialysis patients in Japan: a cross-sectional design. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18(1):233. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01486-x

Kim EY, Lee YN, Chang SO (2018) Exploring subjective frames of patients on hemodialysis on acquiring resilience: a Q methodology study. Nephrol Nurs J 45(4):357–368

Chon MY, Yeun EJ, Jung KH et al (2020) Perceptions of resilience in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis: a Q-methodology study. Nurs Heal Sci 22:108–117

Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T et al (2020) Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry 7:883–892. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4

Mazza C, Ricci E, Biondi S et al (2019) A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(9):3165. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093165

Purnell TS, Auguste P, Crews DC et al (2013) Comparison of life participation activities among adults treated by hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 62:953–973

Welbevinden en leefstijl (2020) RIVM. https://www.rivm.nl/gedragsonderzoek/maatregelen-welbevinden/welbevinden-en-leefstijl. Accessed 1 Nov 2020

COVID-19 Map-Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center (2020) https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed 7 Dec 2020

Loosman WL, Hoekstra T, Van Dijk S et al (2015) Short-Form 12 or Short-Form 36 to measure quality-of-life changes in dialysis patients? Nephrol Dial Transplant 30:1170–1176

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all patients, investigators and study nurses from participating centres of the DOMESTICO study.

Funding

The Dutch nOcturnal and hoME dialysis Study To Improve Clinical Outcomes is supported by grants of ZonMw, Fresenius Medical Care Deutschland GmbH, Baxter Netherlands BV, AstraZeneca and Dirinco. The grant of ZonMw is provided from the ‘Health care efficiency research’ program. ZonMw has independently peer reviewed the study protocol. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study and no role in writing or in the decision to publish this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

AAB, TAD, AES, BCJ, ACA. designed the research question. AAB performed the statistical analyses. AAB and TAD drafted the manuscript. AAB, AES, BCJ, ACA interpreted the data. FJI provided intellectual content of critical importance to the work described. All authors critically edited the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

AES has received speaker honoraria from Baxter Healthcare. ACA has received speaker honoraria from Fresenius Medical Care and Baxter Healthcare. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Primary ethical approval was obtained from the medical research ethics committee of the VU University Medical Center Amsterdam (reference number: 2017.491). The DOMESTICO study is conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO).

Informed consent

All participants provided informed consent prior to their participation.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bonenkamp, A.A., Druiventak, T.A., van Eck van der Sluijs, A. et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of dialysis patients. J Nephrol 34, 337–344 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-021-01005-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-021-01005-1