Abstract

Background

Routine clinical evidence is limited on clinical outcomes associated with anemia in patients with severe chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Methods

We linked population-based medical databases to identify individuals with severe CKD (eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2) in Northern Denmark from 2000 to 2016, including prevalent patients as of 1 January 2009 or incident patients hereafter into the study. We classified patients as non-anemic (≥ 12/≥ 13 g/dl hemoglobin (Hgb) in women/men), anemia grade 1 (10–12/13 g/dl Hgb in women/men), 2 (8–10 g/dl Hgb), and 3+ (< 8 g/dl Hgb), allowing persons to contribute with patient profiles and risk time in consecutively more severe anemia grade cohorts. Patients were stratified by dialysis status and followed for clinical outcomes.

Results

We identified 16,972 CKD patients contributing with a total of 28,510 anemia patient profiles, of which 3594 had dialysis dependent (DD) and 24,916 had non-dialysis dependent (NDD) severe CKD. Overall, 14% had no anemia, 35% grade 1 anemia, 44% grade 2 anemia and 17% grade 3+ anemia. Compared to patients with no anemia, adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for NDD patients with grade 3+ anemia were elevated for incident dialysis (1.91, 95% CI 1.61–2.26), any acute hospitalization (1.74, 95% CI 1.57–1.93), all-cause death (1.82, 95% CI 1.70–1.94), and MACE (1.14, 95% CI 1.02–1.26). Similar HRs were observed among DD patients.

Conclusions

Among NDD or DD patients with severe CKD, presence and severity of anemia were associated with increased risks of incident dialysis for NDD patients and with acute hospitalizations, death and MACE for all patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anemia is common in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and prevalence increases with CKD severity [1]. Renal erythropoietin-producing cells sense low tissue oxygen tension and respond by the production of erythropoietin, a hormone that stimulates red blood cell production [2]. CKD leads to a disruption of this process, erythropoietin deficiency and subsequent anemia, characterized by lower than normal number of circulating red blood cells or decreased levels of hemoglobin (Hgb) [3]. Other possible causes of anemia include blood loss, iron deficiency, inflammation and accumulation of uremic toxins [4]. Prevalent anemia in CKD has been associated with cognitive impairment, sleep disturbances, CKD progression, cardiovascular disease and higher mortality in mostly older studies and in selected populations [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13], whereas contemporary unselected population-based data on clinical outcomes associated with anemia are scarce. Treatment options for anemia include iron (oral and intravenous), erythropoietin stimulating agents (ESAs) and red blood cell transfusion to restore hemoglobin levels. Concerns have been raised regarding the cardiovascular safety of treating anemia to higher Hgb levels, in particular when using ESAs to target Hgb levels > 12 g/dl [14,15,16]. This has resulted in a change of anemia management practices since 2011, with generally less intensive therapy and lower Hgb treatment targets [17, 18]. Following this change, high-quality longitudinal real-world data on the current impact of anemia on clinical outcomes are scarce. Furthermore, the exact risk of cardiovascular and other adverse outcomes in patients following progression to more severe anemia remains unknown.

The overall aim of our study was to identify major clinical consequences of anemia in dialysis dependent (DD) and non-dialysis dependent (NDD) patients with severe CKD. Specifically, we examined the association between anemia and time to first dialysis (in NDD patients) and major cardiovascular events (MACE), acute hospitalizations and all-cause death (in NDD and DD patients).

Methods

We linked Danish population-based healthcare and administrative databases including all laboratory plasma-creatinine tests from primary and hospital care from The Laboratory Information Systems Database (LABKA) [19], all hospital contacts and diagnoses from The Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR), and all drug prescriptions from The Aarhus University Prescription Database [20, 21] for the entire population in Northern Denmark from 2000 through 2016 where residence, migration and vital status was obtained from The Civil Registration System (CRS). The cumulative source population comprised of ~ 2.2 million persons from which we included a study population with prevalent severe CKD at study start on Jan 1, 2009 (identified from 2000 to 2008), or with incident severe CKD between 2009 and 2016.

Study population

Patients with severe CKD were defined as individuals with two plasma-creatinine tests at least 3 months (90 days) apart showing an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the period 2000–2016. eGFR was computed by the simplified Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation based on creatinine measurements, taking sex and age and into account [22].

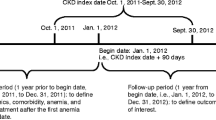

During 2009–2016, we assigned CKD patients (who had either prevalent severe CKD on Jan 1, 2009 or incident severe CKD between 2009 and 2016) to different anemia grade cohorts.

We excluded patients with any of the following at any time prior to the index date: any cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer), hereditary hematologic disease, chronic inflammatory disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, or organ transplants.

Anemia

Anemia grades were classified as no anemia (Hgb level of ≥ 12/≥ 13 g/dl in women/men); grade 1 (Hgb level of 10 to < 12/< 13 g/dl in women/men); grade 2 (Hgb level of 8 to < 10 g/dl) and grade 3+ (Hgb level of < 8 g/dl) [23]. For prevalent severe CKD patients, anemia grade was determined based on the lowest Hgb recording during a 1 year lookback period from Jan 1st 2009. If Hgb was not measured in this period, the follow up started following the first recorded Hgb measurement after Jan 1st 2009. For incident severe CKD patients, follow up began on the date of the second measurement showing an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 after Jan 1st 2009 if Hgb measurements were recorded within 1 year before that date. For these patients, anemia grade was determined based on the lowest Hgb recording during that year. If no prior Hgb measurements were available, follow up started following the first available Hgb measurement after the patient’s second eGFR measurement below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. A schematic presentation of inclusion of prevalent severe CKD patients is shown in Fig. 1a and similarly for incident severe CKD patients in Fig. 1b. Patients could be included in more than one anemia grade cohort if they “moved up” in anemia grade; i.e., one person was allowed to contribute risk time in consecutively more severe anemia grade cohorts. Since our aim was to predict the subsequent outcome risk for a given CKD patient from the date of first reaching a specific anemia grade, patients were not censored from the cohort at time following inclusion into a more severe anemia grade cohort and were not re-entered into a lower anemia grade cohort once they were included in a more severe grade cohort irrespective of the results of subsequent Hgb measurements.

Outcomes

Study outcomes were: (1) incident dialysis (among NDD patients only) defined as a first ever record of dialysis (acute or chronic) during follow-up; (2) all-cause acute hospitalization, defined as an acute inpatient record in DNPR during follow-up; (3) all-cause death, defined as death before the end of follow-up; (4) MACE (composite of tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) codes for myocardial infarction [I21–I23], unstable angina pectoris [I200], stroke [I61, I63 and I64], or heart failure [I50]); and (5) fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events (CVE) separately (composite and individual). Patients who were already hospitalized at the index date were not considered at risk of an acute hospitalization and thus excluded from this analyses.

Data analysis

For the incident severe CKD patients, we generated cumulative incidence function curves for incident dialysis among NDD patients and for CVE and all-cause death stratified by dialysis status at time of entry in each anemia grade cohort.

For both prevalent and incident severe CKD patients, we computed incidence rates per 100 person years and estimated adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) using Cox regression. To account for the dependency between observations, we used the robust sandwich estimator to compute 95% CIs [24]. HRs were simultaneously adjusted for the following covariates assessed at the start of follow-up in each anemia grade cohort: age, gender, marital status, severe CKD duration (time since 2nd eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2), last measured eGFR level, Charlson Comorbidity Index [25] (based on complete hospital contact history, excluding CVE and renal disease categories), alcohol dependency related disorders, previous history of CVE and number of acute hospitalizations 1 year before anemia.

Since the proportional hazard assumption was not fulfilled for incident dialysis, angina and acute hospitalization in the NDD population and for all outcomes in the DD population, supplementary analyses were performed dividing the analyses into 0–2 years and 2–8 years of follow-up.

Since the average age of the included study population was relatively high we performed a stratified analyses by ages < 65 and 65 + years, and as diabetes is associated with increased baseline risk of the included outcome events we also performed stratified analyses by diabetes status.

Results

In total, we included data from 16,972 unique patients with severe CKD, who contributed to one or more of the anemia grade cohorts over time, resulting in a total of 28,510 patient profiles across all anemia cohorts. These included 24,916 (87%) NDD and 3594 (13%) DD patients, with different anemia grades. Characteristics are shown for all patients in Table 1, for NDD patient profiles in Supplementary Table 1, and for DD patient profiles in Supplementary Table 2.

Overall we identified 4105 (14%) patient profiles with no anemia, 10,033 (35%) with anemia grade 1, 9631 (34%) with anemia grade 2 and 4740 (17%) with anemia grade 3+.

The duration of severe CKD, the number of acute hospitalizations (within the last year), the proportion of patients on dialysis, with low eGFR (< 15 ml/min/1.73 m2) and with a high comorbidity score all increased with increasing anemia grade (Table 1).

The incidence rates of incident dialysis among NDD patients and of acute hospitalization, all-cause deaths and MACE among all patients (Table 2) increased markedly with increasing anemia grades both when analyzing crude incidence rates per 100 person years (IR) and hazard ratios for clinical outcomes by anemia grade, and when these were adjusted for baseline differences in potential confounders (Table 2). The adjusted estimates were attenuated compared to the crude estimates. Among the NDD patients, the IR for newly initiated dialysis at anemia grade 3+ was 8.6 per 100, 95% CI 7.8–9.5 and the adjusted HR was markedly elevated (HR 1.91, 95% CI 1.61–2.26) at anemia grade 3+ when compared to no anemia. Anemia was strongly associated with acute hospitalization for any cause (IR at anemia grade 3 + 103.9, 95% CI 96.4–111.8 and HR 1.74, 95% CI 1.57–1.93) and with all-cause death (IR at anemia grade 3+ 39.4, 95% CI 37.8–41.1 and HR 1.82, 95% CI 1.70–1.94). The HR for MACE at anemia grade 3+ was only modestly elevated, although statistically significant (IR at anemia grade 3+ 15.4, 95% CI 14.3–16.6 and HR 1.14, 95% CI 1.02–1.26). Among the individual MACE endpoints, heart failure revealed the strongest association with anemia (IR at anemia grade 3+ 10.7, 95% CI 9.8–11.6 and HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.09–1.41).

For the DD population (Table 3), similar risk estimates as in the NDD population were observed for acute hospitalization (IR 121.9, 95% CI 109.8–135.0 and HR 1.51, 95% CI 1.20–1.90) all-cause death (IR 23.4, 95% CI 21.6–25.0 and HR 1.91, 95% CI 1.50–2.43) and MACE (IR 10.4, 95% CI 9.3–11.7 and HR 1.16, 95% CI 0.84–1.61) although the estimates were less precise, probably due to lower number of subjects included in the analyses.

Fatal MACE were more strongly associated with anemia (HR 1.42, 95% CI 1.19–1.68) than non-fatal events (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). In particular, fatal events of stroke, myocardial infarction and unstable angina were associated with anemia, while similar non-fatal events revealed HRs close to one. Both fatal and non-fatal heart failure events were clearly associated with anemia in both the NDD and the DD patients.

In supplementary analyses, outcomes were evaluated based on follow up time dividing this into 0–2 years and 2–8 years. Among the NDD patients, the HRs for incident dialysis, acute hospitalization and all-cause death associated with anemia grade 3+ compared to no anemia were markedly higher during the first 2 years of follow up when compared to 2–8 years (Supplementary Table 5). Similarly, in DD patients higher HRs for acute hospitalization and all-cause death associated with anemia were observed during the first 2 years when compared to 2–8 years (Supplementary Table 6).

Stratification by age < 65 years and 65+ years and by presence or absence of diabetes revealed similar results to the comparator, indicating that these were not key effect modifiers (data not shown). NDD patients with a known hospital history of heart failure at baseline had lower HRs than those without previously known heart failure for death (HR 1.55, 95% CI 1.38–1.74 vs HR 1.97, 95% CI 1.82–2.13), incident heart failure hospitalization (HR 1.11, 95% CI 0.93–1.32 vs HR 1.55, 95% CI 1.28–1.88) and MACE (HR 1.04, 95% CI 0.89–1.23 vs HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.12–1.48). For the DD population similar but less precise estimates were obtained (data not shown).

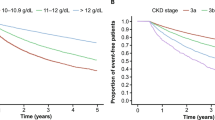

Cumulative incidence function curves for study outcomes in NDD and DD patients are shown in Fig. 2a–g. The risk of dialysis initiation in NDD patients as well as the risks for acute hospitalization and all-cause death among both NDD and DD increases successively with increasing anemia grades. The risk of MACE increased modestly with higher anemia grades among NDD patients, while no clear association was observed among DD patients (Fig. 2a–e).

Cumulative incidence curves for patients with incident severe CKD. a incident dialysis for non-dialysis dependent patients; b acute hospitalization for non-dialysis dependent patients; c acute hospitalization for dialysis dependent patients; d all-cause mortality for non-dialysis dependent patients; e all-cause mortality for dialysis dependent patients; f cardiovascular events for non-dialysis dependent patients; g cardiovascular events for dialysis dependent patients

Discussion

In the current setting of less frequent treatment of NDD anemia and treatment to lower Hgb targets among patients with severe CKD and anemia, the present study provides contemporary data showing that increasing grades of anemia in severe CKD patients are associated with increased absolute and relative risks of a number of adverse health outcomes, including dialysis initiation, MACE, acute hospitalization and all-cause death. In general, similar results were seen among DD and NDD patients.

Compared with previous cross-sectional studies of anemia prevalence in CKD, we observed higher proportions of severe CKD patients experiencing grade 2 or 3 anemia at any given point of time, likely due to the longitudinal nature of our study enabling us to identify incident anemia events. Our results corroborate earlier findings on the association between anemia and clinical outcomes in smaller and selected populations from the United States or Japan [5, 11,12,13].

The observed and markedly increased HR of incident dialysis, acute hospitalization, all-cause death and MACE during the first 2 years after anemia may indicate that CKD four to five patients surviving the first 2 years after anemia have an only slightly elevated, subsequent risk of adverse events when compared to non-anemic patients. This interpretation, however, is limited by the fact that only survivors were followed in this study. In addition, in this study anemia grade was defined by the lowest Hgb level observed during 1 year before inclusion. This Hgb level may not have been constant during the follow-up period. Since our analyses did not differentiate between patients with sustained and chronic anemia and patients with acute anemia or anemia that was corrected during follow up, our risk estimates may have underestimated the effects of chronic anemia on long term adverse outcomes. Future studies should look into the causes and mechanisms through which increased anemia associates with acute hospitalizations and death, other than CVE.

This study was a population-based study using extensive registry health data. This is a major strength of the study since the universal health care system in Denmark implies that all individuals with contact to the hospital system are included in the registers thereby providing an unselected real-world study population. Also, compared to previous studies we were able to include a large study population of 16,930 patients with severe CKD, with ascertainment of progressing anemia over time. We could follow these patients longitudinally for up to 8 years after anemia and adjust our outcome estimates for a large set of relevant confounders. In general, the registration of exposures and outcomes in the included databases is accurate and the validity of registration of major diagnoses including cardiovascular diseases in the Danish National Patient Registry is high [26, 27].

Several limitations also apply to the study. The inclusion of severe CKD patients relied on routine plasma-creatinine measurements and some misclassification of CKD patients may occur based on missing or infrequent plasma creatinine measurements to determine CKD stage. Although the definition of CKD was based on registered eGFR measurements and the diagnosis was not verified by a nephrologist, we do not expect this to be associated to major misclassification of CKD, since we used the common definition of CKD as specified above. The estimation of GFR was based on the MDRD equation, which was the predominant equation used in clinical practice throughout the period of data collection. Currently, the CKD-EPI equation is more often used. The divergence between the equations occurs mainly at eGFR values > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 [28], and thus, this most likely has limited impact on the results of the present study.

Sicker patients with more severe CKD may have had a higher likelihood of any anemia being detected due to higher frequency of Hgb testing, leading to potential overestimation of anemia and possibly also its clinical consequences. However, our patients all had severe CKD and are all likely to receive regular blood test monitoring including Hgb in a universally covering healthcare system. We did not have complete treatment data for ESAs, iron, and transfusions recorded in our prescription registries. Therefore, the effects of anemia alone from the potential adverse effects of anemia treatment could not be differentiated in our study. It is likely that patients with severe anemia and late stage CKD did receive ESAs, IV iron or RBC transfusions occasionally, as is suggested by international guidelines [29, 30]. Overall, our results suggest that higher Hgb levels are associated with better outcomes; however, the potential positive or negative effects of anemia treatment cannot be assessed from this study.

Finally, we did not account for differences in blood pressure and proteinuria, and we cannot exclude unmeasured confounding from e.g. smoking, socioeconomic status or lifestyle factors on which did not have reliable data, or from other, unknown confounding factors.

Conclusions

The presence and increasing severity of anemia were associated with a substantially increased risk for progression to dialysis in non-dialysis patients with CKD stage 4–5, and with an increased risk for acute hospitalization and all-cause death both in non-dialysis and dialysis patients. The presence and increasing severity of anemia was also associated with a moderately elevated risk of MACE which was more pronounced during the first 2 years after entering a lower anemia grade and with particularly increased risks of heart failure and fatal CVE. In the current setting of generally less intensive anemia therapy, the present large study emphasizes the need for awareness of the potential risk of adverse clinical events in patients with CKD and anemia, and for further exploration of the interaction between anemia and progressive disease in CKD.

References

Stauffer ME, Fan T (2014) Prevalence of anemia in chronic kidney disease in the United States. PLoS One 9:e84943

Nolan KA, Wenger RH (2018) Source and microenvironmental regulation of erythropoietin in the kidney. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 27:277–282

Shih HM, Wu CJ, Lin SL (2018) Physiology and pathophysiology of renal erythropoietin-producing cells. J Formos Med Assoc = Taiwan yi zhi 117:955–963

Babitt JL, Lin HY (2012) Mechanisms of anemia in CKD. JASN 23:1631–1634

Thorp ML, Johnson ES, Yang X, Petrik AF, Platt R, Smith DH (2009) Effect of anaemia on mortality, cardiovascular hospitalizations and end-stage renal disease among patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrology 14:240–246

Stevens LA, Viswanathan G, Weiner DE (2010) Chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the elderly population: current prevalence, future projections, and clinical significance. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 17:293–301

Yamamoto T, Miyazaki M, Nakayama M, Yamada G, Matsushima M, Sato M et al (2016) Impact of hemoglobin levels on renal and non-renal clinical outcomes differs by chronic kidney disease stages: the Gonryo study. Clin Exp Nephrol 20:595–602

Keane WF, Brenner BM, de Zeeuw D, Grunfeld JP, McGill J, Mitch WE et al (2003) The risk of developing end-stage renal disease in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy: the RENAAL study. Kidney Int 63:1499–1507

Abramson JL, Jurkovitz CT, Vaccarino V, Weintraub WS, McClellan W (2003) Chronic kidney disease, anemia, and incident stroke in a middle-aged, community-based population: the ARIC Study. Kidney Int 64:610–615

Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Vlagopoulos PT, Griffith JL, Salem DN, Levey AS et al (2005) Effects of anemia and left ventricular hypertrophy on cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. JASN 16:1803–1810

Levin A, Djurdjev O, Duncan J, Rosenbaum D, Werb R (2006) Haemoglobin at time of referral prior to dialysis predicts survival: an association of haemoglobin with long-term outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21:370–377

Kovesdy CP, Trivedi BK, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Anderson JE (2006) Association of anemia with outcomes in men with moderate and severe chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 69:560–564

Yotsueda R, Tanaka S, Taniguchi M, Fujisaki K, Torisu K, Masutani K et al (2018) Hemoglobin concentration and the risk of hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke in patients undergoing hemodialysis: the Q-cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 33:856–864

Phrommintikul A, Haas SJ, Elsik M, Krum H (2007) Mortality and target haemoglobin concentrations in anaemic patients with chronic kidney disease treated with erythropoietin: a meta-analysis. Lancet 369:381–388

Pfeffer MA, Burdmann EA, Chen CY, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Eckardt KU et al (2009) A trial of darbepoetin alfa in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 361:2019–2032

Mc Causland FR, Claggett B, Burdmann EA, Chertow GM, Cooper ME, Eckardt KU et al (2019) Treatment of anemia with darbepoetin prior to dialysis initiation and clinical outcomes: analyses from the trial to reduce cardiovascular events with aranesp therapy (TREAT). Am J Kidney Dis 73:309–315

Park H, Liu X, Henry L, Harman J, Ross EA (2018) Trends in anemia care in non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients in the United States (2006–2015). BMC Nephrol 19:318

Stivelman JC (2017) Target-based anemia management with erythropoiesis stimulating agents (risks and benefits relearned) and iron (still more to learn). Semin Dial 30:142–148

Grann AF, Erichsen R, Nielsen AG, Froslev T, Thomsen RW (2011) Existing data sources for clinical epidemiology: the clinical laboratory information system (LABKA) research database at Aarhus University, Denmark. Clin Epidemiol 3:133–138

Ehrenstein V, Antonsen S, Pedersen L (2010) Existing data sources for clinical epidemiology: aarhus University Prescription Database. Clin Epidemiol 2:273–279

Pottegard A, Schmidt SAJ, Wallach-Kildemoes H, Sorensen HT, Hallas J, Schmidt M (2017) Data resource profile: the Danish national prescription registry. Int J Epidemiol 46:798

Levey AS, Greene T, Kusek JW, Beck GJ (2000) A simplified equation to predict glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine. JASN. 2000(11):155A

KDIGO (2012) Chapter 1: diagnosis and evaluation of anemia in CKD. Kidney Int Suppl 2:288–291

Lin DY, Wei LJ (1989) The robust inference for the cox proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc 84:1074–1078

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383

Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT (2015) The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol 7:449–490

Sundboll J, Adelborg K, Munch T, Froslev T, Sorensen HT, Botker HE et al (2016) Positive predictive value of cardiovascular diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry: a validation study. BMJ Open 6:e012832

Levey AS, Inker LA, Coresh J (2014) GFR estimation: from physiology to public health. Am J Kidney Dis 63:820–834

Summary of Recommendation Statements (2012) Kidney Int Suppl 2:283–287

Mikhail A, Brown C, Williams JA, Mathrani V, Shrivastava R, Evans J et al (2017) Renal association clinical practice guideline on Anaemia of chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol 18:345

Acknowledgements

The present study, received funding in part from AstraZeneca.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

HvH, GJ and KH are employees and stockholders of AstraZeneca. GT, UHJ, HB, RWT and CFC do not report any personal conflicts of interest relevant to this study. The Department of Clinical Epidemiology is, however, involved in studies with funding from various companies as research grants to (and administered by) Aarhus University. This includes the present study, which received funding in part from AstraZeneca.

Approval of research involving human participants and informed consent

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. No approval from an ethics committee or informed consent from patients is required for registry studies in Denmark.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Toft, G., Heide-Jørgensen, U., van Haalen, H. et al. Anemia and clinical outcomes in patients with non-dialysis dependent or dialysis dependent severe chronic kidney disease: a Danish population-based study. J Nephrol 33, 147–156 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-019-00652-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-019-00652-9