Abstract

The rate of suicidality is increasing faster in Black American youth than in any other group in the USA. Researchers have found that family-level factors are important environmental factors for predicting depression and anxiety among Black youth, but less is known about how family- and friendship-level factors are associated with suicidal ideation and attempts among Black youth. This secondary analysis used the data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescents to Adult Health with a sample of Black adolescents (N = 4232) with a mean age of 16 years. The predictors included parental and other contextual factors on the outcome, which was suicidal behaviors. A multinomial analysis was employed to assess which factors contributed to or prevented suicidal behaviors. Our results indicated that parental support was significantly and positively associated with reporting suicidal ideation and attempts. The results indicated that Black youth with a decrease in parental support were 41% more likely to report ideation and 68% more likely to report attempting suicide compared to those reporting no parental support. Findings from our study support the assertion that the influence from the familial microsystem is pronounced in modifying suicidal behavior of Black youth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Emerging research is demonstrating that, among the population of youth with histories of suicidal behavior, Black youth are the group with the most rapidly increasing rate of engaging in suicidal behavior and dying by suicide in the USA [1, 2]. Based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), studies have found that suicide was the second leading cause of death in youth aged between 10 and 24 years old in 2018 [3]. This statistic is extremely concerning because recent research has found that self-reported suicide attempts among Black youth increased by 73% between 1991 and 2017, while suicide attempts among White non-Hispanic youth decreased during the same period [2]. The suicide rates among Black youth under 13 years old are two times higher compared to White non-Hispanic youth in the same age group between 2001 and 2015 [1]. Due to the alarming increase in suicide rates among Black youth along with the lack of intergenerational economic mobility for Black families [4], more evidence is needed regarding the protective factors that can be utilized as a buffer against suicidal behavior.

Ecodevelopmental theory

The ecodevelopmental theory comprises three main elements: (a) social ecological theory, (b) developmental theory, and (c) an emphasis on social interactions. The social ecological theory is an extension of Bronfenbrenner’s social-ecological model, which frames the social ecology of an individual as a group of four interrelated systems: microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem [5, 6]. We used this theory because it incorporates both risk and protective processes to investigate how the family context (i.e., parent support, parent relationships) influences the suicidal behavior prevalent among Black youth. The ecodevelopmental theory emphasizes the role of family functioning and interactions among risk and protective processes from a developmental lens [7]. In this study, we focused on Black youth and the role of their families as highly influential microsystems in their lives. Other important microsystems include peers, school, and neighborhood systems. We also understand it is critical to recognize intersecting identities of Black youth and how these identities may operate in the family context. Intersectional theory is the belief that social identities, such as race and gender, intersect in a distinct way such that each identity can only be defined through the intersection with other identities [8]. In understanding these increasing number of suicides, suicide attempts, and ideations among Black youth, we must also consider how these intersecting factors in the family context contribute to or prevent their risk for suicide. This is noteworthy to understand because the primary and most powerful system of influence is the family [7]. Therefore, family support is key to reducing the risk of suicidal behaviors among Black youth [1, 2, 9,10,11,12]. Previous study findings have shown that appropriate family support and communication between parents and youth could prevent the onset of depression and anxiety and, but there is a dearth of literature on how family support reduces the risk of suicidal behaviors among youth [1, 10, 13, 14]. Guided by the ecodevelopmental theories, this study seeks to investigate whether family support (i.e., parental support, parent-youth relationships, peer suicidal behavior, and youth depression) impacts suicidal ideation and attempts among Black youth.

Environmental factors and suicidal ideation and attempts among Black Americans

Researchers have highlighted specific environmental factors for Black Americans that act as both protective and risk factors for suicidal outcomes [15,16,17,18] including poverty and racial discrimination [19,20,21]. Furthermore, lack of social support has been connected to more suicidal ideation for Black emerging adults ages 18 to 29 [15]. Conversely, researchers have identified the importance of social support, such as family support and friendship with peers, as protective factors for Black Americans [22,23,24,25]. While positive family support and relationships have been identified as protective factors for Black Americans, less is known about how family-level factors and peer support influence suicidal ideation and attempts for Black youth [26].

Family-level factors and suicidal ideation and attempts among youth

A substantial amount of the existing literature on social support and suicidal ideation and attempts among youth and emerging adults has established that family-level factors are essential to consider when assessing suicidal outcomes [2, 3, 9]. Specifically, research indicates that family support (e.g., parental warmth, parent-youth relationships, and family members) is a significant protective factor against the risk of suicidal ideation and attempts among youth [27, 28]. Research focused on family-level factors for Black Americans aged 18 years old and older found greater levels of emotional support from the family was associated with a lower risk of suicidal attempts [29]. Furthermore, research focused on Black college students found that family support is associated with decreased suicide risk [25]. Conversely, the lack of or varying levels of family support is also important to consider; one study of ethnic and minority (African American and Latino), found that those who reported suicide attempts were more likely to report a lack of access to a family network [ 27]. In a national study of general population adolescents, Kim et al. [30] found that even when adolescents received high levels of parental monitoring, if they did not have social support, their depression levels could increase which could increase their suicidal ideation. Although there is some evidence that family-level factors are associated with decreased suicidal outcomes for Black Americans, there is a lack of empirical literature that examines how specific family-level factors are associated with suicidal outcomes among Black youth.

Friendship factors and youth suicidal ideation and attempts

In addition to family-level factors, several scholars have highlighted friendship factors (i.e., lacking friends, having close friends, engaging with delinquent friends) to be of importance in the examination of youth suicidal behavior [31,32,33]. Specifically, evidence suggests that social support from friends can act as a protective factor against suicidal attempts among adolescents [34]. Furthermore, results from some empirical studies revealed that having a friend who has attempted suicide in the past was a significant risk factor for suicidal outcomes [35, 36]. In a study focused on African American adolescents, researchers found that increased peer support was associated with decreased suicidality [23]. Overall, aspects of friendship are an important factor to take into consideration concerning suicidal ideation and attempts among youth. Despite the importance of friendship factors demonstrated in the research literature, limited studies have been conducted about how a friend’s suicidal behavior influences suicidal outcomes among Black youth.

Present study

Prior research has indicated that family-level factors (i.e., family support, positive parenting, and parental monitoring) are important environmental factors for predicting depression and anxiety among Black youth [37,38,39]. However, less is known about the family and friendship level factors associated with suicidal ideation and attempts in this group. This study assessed both suicidal ideation and attempts because evidence has consistently found that suicidal ideation is a considerable predictor of suicide attempts and death by suicide [11, 12, 40, 41]. Given the urgency of this public health crisis, this paper aimed to explore the impact of family-level factors and the suicidal behavior of friends on suicidal ideation and attempts among Black youth. We predicted that higher levels of positive parent support would be associated with lower suicidal ideation and attempts, while increased friends’ suicidal behaviors would be positively associated with higher suicidal ideation and attempts among Black youth.

Method

Participants and procedures

The data for this study came from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), a nationally representative cohort study based in the USA [42]. Additional health data were collected from 1994/95 to 2008 to survey adolescents and their parents over time using complex survey weights and clustering. The respondents were recruited during the 1994–1995 school year (Wave 1) in grades 7–12 and last surveyed in 2016–2018 (Wave 5). A wide range of information was collected across four waves from the respondents to examine the social, emotional, physical, and health domains. The details of the sample design have been described elsewhere [42]. The sample was taken from a stratified probability sample of 134 schools in the USA (79% of those sampled). An in-school survey was completed by 90,118 students, and 20,745 students participated in an additional, detailed in-home interview (75.6% and 79.5% of eligible students, respectively). During the in-home interview, 85% of students’ parents were also interviewed (85%, n = 17,760) [42, 43]. Three subsequent follow-up interviews were conducted, including an in-home interview in 2008–2009 during Wave 4.

For this study, we used data from ADD health Wave 1 in-home interviews comprising 4232 Black males (50%) and females (50%) between the ages of 11–21. The average age in the sample is 16 years (SE = 0.21). Approximately 35% of parents received a high school diploma, while 35% did not complete high school, 12% reported their parents received some college or technical training, and 17% reported their parent graduated from college or professional school. The variables for this study were obtained from household surveys.

Measures

The outcome variable for this study, suicidal behaviors, was assessed by the following questions: “During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously think about committing suicide” and “During the past 12 months, did you attempt suicide?” This three-level polytomous response outcome variable is a measure of suicide ideation and attempts (1 = No suicide ideation; 2 = Yes, suicide ideation and no attempts; 3 = Yes, suicide ideation and yes, suicide attempts) [44].

Several contextual variables were collected. The participants were asked to indicate their age, gender, and parent's education level. The participants were asked about their parents’ education level based on the following question: “How far in school did he/she go?” (1 = less than high school, 2 = high school or GED, 3 = some college or colleges, 4 = 5 years of college or more, and 5 = graduate or professional school). The respondents were also asked about their age, which was reported as a continuous variable. The participants self-reported their gender (0 = male, and 1 = female).

Several measures and single items were used to assess the socio-cultural variables. Perceived parental support was measured with an average score from seven items that asked about the respondents’ perceptions of support (mother and father communication and mother and father bonding) from the people they identified as “mother” and “father.” Sample items include (i.e., “Did you talk about someone you’re dating or a party you went to?” and “Did you talk about school, work, or grades?”). The participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) with a higher score indicating more parental support. This method of measuring parental support was drawn from prior literature, which found strong evidence for internal consistency (α = .86 and .87) of the parental scale scores. To review evidence of convergent validity, see [44]. The Cronbach alpha of the scores was .90 for the mother’s items was and .89 for the father’s [44].

Parent relationships were measured by a six-item Likert-type scale (with values ranging from 0 = No and 1 = Yes). Sample items include (“Do your parents let you make your own decisions about what you wear?” and “Do your parents let you make your own decisions about the people you hang around with?”). This measure has been used with a national sample of Black youth and young adults [45] with reliability estimates of the scores ranging from .65 to .84 [45,46,47]. We were unable to locate published studies that report factor structure and further validity of the parent relationship scale [48].

Friends’ suicidal behaviors were measured using a single-item measure (0 = No, 1 = Yes), and the respondents were asked the following question: “Have any of your friends tried to kill themselves during the past 12 months?”

Depression symptomology was measured using 20 items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [49]. While CES-D was developed as a screening tool to assess clinical depression among adults ages 18 or older, it has been used in other populations, including child, adolescent, elderly, ethnic, and clinical populations [50,51,52]. In general, the instrument has exhibited good content, criteria, and discriminant validity across different populations [51, 53]. Participants were asked to rate the extent of the various symptoms of depression they have experienced on a scale from 0 (never) to 3 (most of the time or all the time). The sample items included the following: “You were bothered by things that usually don’t bother you” and “You felt that you were just as good as other people.” CES-D scores were found to be significantly higher among the sample respondents who reported a suicide attempt (M = 19.59, SE = .37) than those who had not attempted suicide (M = 16.41, SE = .53; p < .001).

The CES-D using 20 items was validated with Black youth ages 11 to 21 (N = 782). Reliability analysis for data on the 20 items resulted in a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90, indicating good internal consistency [54]. The items presented good discrimination, with item-total correlations exceeding acceptable standards (r > 0.40) on all items except for “I enjoyed life” (r = 0.246) [54, 55]. A 2-factor ESEM model demonstrated satisfactory fit to our data (CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.04). For convergent validity, a two-factor ESEM model with covariates provided an acceptable fit to the data (CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.03, WRMR = 0.72).

Statistical analysis

All the analyses were conducted on observations that included non-missing data from the outcome variable, suicidal behaviors (1 = No suicide ideation; 2 = Yes, suicide ideation and no attempts; 3 = Yes, suicide ideation and yes, suicide attempts). First, a descriptive analysis was conducted to explore each variable in the dataset separately and to provide a demographic background for the sample. Next, statistical association tests were conducted between the measures described in the method section and the outcome variable, suicidal behaviors. The bivariate analyses were conducted by generating multinomial logistic regression (MLR) models of the measures and the outcome variable. After the bivariate analyses, an MLR model was run with the outcome with measures entered in the model simultaneously. Accordingly, MLR is appropriate for the three-level polytomous response outcome variable because there were more than two categories, and it can accommodate continuous and categorical measures. The reference category was “no suicidal ideation.” More specifically, the results focused on the contrasts involving (1) yes, suicide ideation and no attempts, and (2) yes, suicide ideation and attempts. For the MLR analysis, relative risk ratios (RRR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented. An MLR is an extension of a binary logistic regression that allows for more than two categories of the outcome variable. This ratio is called the relative risk or odds and its log is called the generalized logit. Moreover, the STATA mlogit command only reports RRR, which is an extension of odds ratios. In accordance with the research of Starkweather, and Moske [56], a multinomial analysis was conducted along with the reporting of RRR. Survey data were analyzed based on listwise deletion. For survey scales, a mean score of the scale items was generated for the participants with non-missing data. All the analyses were weighted and accounted for with the complex multi-stage clustered design of the Add Health sample. The analysis was conducted using STATA 16.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for categorical variables. Approximately, 88% of the respondents stated that they had never thought about suicide or attempted suicide, 8% of the respondents stated that they thought about suicide but never attempted it, and 4% stated that they thought about suicide and had attempted suicide. About 12% of respondents reported that a friend had attempted to die by suicide in the past 12 months. Table 2 presents the means, standard errors, range, skewness, and kurtosis for all continuous variables. Black youth reported below-average parent support (M = 2.29, SE = 0.21). Black youth reported positive relationships (M = 4.35, SE = 0.03). Black youth reported low depressive symptoms (M = 4.35, SE = 0.03).

Bivariate regression

Table 3 presents bivariate regression analyses on suicidal ideation and attempts from the following predictors, parent support, parent relationships, depression, age, and parent education on the outcome of suicide behaviors. All assumptions of multicollinearity, homoscedasticity, and normality were met. Black youth who reported a decrease in parental support were 49% more likely to report suicidal ideation but not attempt suicide, in comparison to those who did not report suicidal ideation or suicide attempts (RRR: .51, 95% CI: 0.30, 0.86). Youth who had a 39% decrease in family relationships were more likely to report suicidal ideation but not suicide attempts (RRR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.46, 0.80). Black youth who had friends that attempted suicide in the past 12 months were 3.46 times more likely to report suicidal ideation but not attempt suicide (RRR: 3.46; 95% CI: 2.32, 5.15).

Black youth with a decrease in parental support were 76% more likely to report suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (RRR: 0.24, 95% CI: 0.12, 0.49). A decrease in parent relationships for youth resulted in a 58% increase in suicidal ideation and attempts (RRR: 0.42; 95% CI: 0.26, 0.66). Black youth who had friends that attempted suicide in the past 12 months were 4.70 times more likely to report suicidal ideation and attempts (RRR: 4.70; 95% CI: 2.93, 7.53).

Multinomial analysis

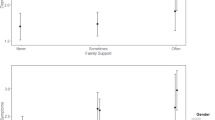

The results of the multinomial logistic regression analyses are presented in Table 4. The regression analyses included the following variables parent support, parent relationships, depression, age, and parent education on the outcome of suicide ideation attempts. The overall model was statistically significant: F (8,87) = 6.79, p < .001. Black youth with a decrease in parental support were 41% more likely to report ideation but not attempt suicide (RRR: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.34, 0.92). Youth who had a decrease in family relationships were 40% more likely to report suicidal ideation or attempts (RRR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.46, 0.79). Black youth who had friends that attempted suicide in the past 12 months were 4.25 times more likely to report suicidal ideation (RRR: 4.25; 95% CI: 1.95, 9.21).

Youth with a decrease in parental support were 68% more likely to report suicidal ideation and attempts (RRR: 0.33; 95% CI: 0.04, 0.72). Black youth who had a decrease in family relationships were 59% more likely to report suicidal ideation or attempts (RRR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.25, 0.69). Youth who had friends that attempted suicide in the past 12 months were 8.70 times more likely to report suicidal ideation and attempts (RRR: 8.70; 95% CI: 4.11, 18.41).

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to explore the impact of family-level factors on suicidal ideation and attempts among Black youth in the USA. Despite the increasing rates of suicidality among Black youth and the significant public health implications, few studies have examined the contextual factors associated with parental support and relationships with friends specifically. As such, this study investigated suicidal behavior among a national sample of Black youth in the United States using the ecodevelopment theory. We used this theory because it incorporates both risk and protective processes to investigate how the family context (i.e., parental support, parent relationships) impacted the suicidal behavior of Black youth. Overall, our findings suggest that the influence from the familial microsystem is pronounced in modifying suicidal behavior in Black youth. Our results also indicated there were differences between youth who reported suicidal ideations and attempts, which allowed for a more nuanced understanding of how the extent of parental support may affect the health and well-being of this group. We predicted that higher levels of positive parent support would be associated with lower suicidal ideation and attempts, while increased friends’ suicidal behaviors would be positively associated with higher suicidal ideation and attempts among Black youth, both of which were supported by these findings.

Our findings indicated that parent support influenced the suicidal behavior of Black youth. Those with parental support were more likely to report suicidal ideation versus suicide attempts. Furthermore, adolescents who had positive relationships with their parents were also less likely to report suicidal ideation versus suicide attempts. Yet, parental support was also significant and positively associated with disclosing both suicidal ideation and attempts by some Black youth. This relationship implies that youths’ perceptions of their parents’ attitudes and/or beliefs about suicide are quite nuanced—they may perceive more risk associated with disclosing suicide attempts, especially if they do not perceive strong bonds in their family [45, 57]. Moreover, parents’ beliefs have been noted as powerful vehicles to influence their children’s attitudes about other life circumstances and events like sex and healthy sexual behaviors; therefore, suicidal behavior could be similar in this regard [58]. Furthermore, this finding supports previous research regarding parental support and relationships and youth who reported suicide attempts and did not have access to a family network [59]. In this context, some youths’ parents functioned as a microsystem who both favorably and unfavorably influenced Black youth in an ability to discuss their thoughts about suicide and/or engaging in suicidal ideation. One explanation for this finding could be linked to the presence and/or variation in disciplinary practices in Black families [60, 61]. In a study with a community sample of children, Wimsatt et al. [61] noted the child’s experience with their parent/caregiver included but was not limited to positive parent-child communication, with corporal punishment considered a negative type of physical communication; this was the case even when they explained their rationale for discipline [60, 61]. Therefore, Black youth may not feel comfortable disclosing suicidal ideation or attempts because they may fear retaliatory and/or punitive behavior from their parents. There also could be variation in how Black youth might respond to and/or communicate with their fathers and mothers [62, 63].

Consistent with the research findings of peers and youth suicide risk, Black youth with friends who attempted suicide were more likely to report suicidal ideation versus attempts. However, some Black youth had friends who attempted suicide and were even more likely to report both ideation and attempts. This relationship could suggest that youth who report suicidal ideation or attempts may need support that their peers are ill-equipped to provide, which could have a bidirectional effect. Moreover, having a friend who attempted suicide could increase the risk of suicidal ideation and attempts for others in that peer group [2, 36, 64]. Mueller et al. [65] utilized network data from Add Health to gain insights into the emotional and cultural mechanisms that underlie suicidal behaviors within one's family or one's peer group. Specifically, they assessed the effects of their friend’s disclosed and undisclosed suicide attempts, suicide ideation, and emotional distress on the respondent’s mental health one year later. They found that when the respondents knew about a friend’s suicide attempt, they reported significantly higher levels of emotional distress and were more likely to report suicidality. However, the friend’s undisclosed suicide attempts and ideation had no significant effect on the respondents’ mental health. The authors also noted evidence of emotional distress that was contagious in adolescence, yet it did not seem to promote suicidal behavior. In addition, like parents, the quality of peer relationships and/or support is important, especially if the youth lacked close friendships or had poor relationships with peers and friends. Consequently, these factors could be highly associated with suicidal outcomes for youth [27, 29, 32, 33, 66, 67]. In this context, for many youth, their friends functioned as a microsystem who favorably influenced their peers’ ability to discuss their thoughts about suicide and suicidal behavior.

We noted strong positive associations with Black youth reporting ideation but not attempts, given the presence of parental support. Of significance was the fact that nearly half of the sample reported moderate levels of parental support and positive parent relationships. Furthermore, when youth perceived that their parent relationships were positive, they were less likely to report suicidal ideation or attempts. Therefore, Black youth who may have been more likely to report suicide attempts were much less likely to do so if they viewed their family relationships in a positive light. This relationship is important since previous studies with Black adolescents note the variation in depression and anxiety associated with family dynamics like disciplinary practices, or parents’ beliefs about issues like sex or in this case, suicide; parental support and familial relationships were found to be influential on their behavior [9, 60, 68]. In addition, Black youth who had friends who attempted suicide were more likely to report suicidal ideation and attempts. Moreover, even though only 4% of the sample reported thinking about or ever attempting suicide, they were connected to youth who have histories of suicidal behavior. This relationship could be related to unexplained factors that encompass the increased suicide rates among Black youth. There may be behavioral patterns that exist in their microsystem, which need to be further investigated and explained. In addition, there are likely factors across their mesosystem (i.e., religiosity), exosystem, and macrosystem that also need to be investigated over time, including using qualitative methods to explore the meaning behind some of the factors we included in this study. However, these results are based on cross-sectional data, so future research employing longitudinal data could provide a more definitive test of this conclusion.

There is limited evidence regarding protective factors for adolescent suicide, and what exists has produced mixed evidence regarding the impact of family cohesion [9, 69]. Black youth who reported parental support and positive relationships with their families also reported mixed results regarding suicidal ideation or attempts. Previous research findings are clear in variations of these behaviors by gender and race for younger youth with histories of maltreatment as well as young adults (up to age 24) whose parents were incarcerated and engaged in substance misuse [9]. Therefore, it is important to consider avenues for prevention and intervention with younger Black youth and their parents to increase their understanding of suicide and precursory behaviors like depression and anxiety. In addition, past research on social capital, a critical asset and key ingredient in personal well-being within families, has shown a negative correlation with depressive symptoms [2, 4, 70]. Culturally tailored interventions need to incorporate macrosystem factors like socioeconomic status, race, and discrimination as well as systemic factors like system involvement (i.e., juvenile justice and child welfare) to ensure that the context of needs is addressed with Black families. Specifically, interventions that focus on racial/ethnic identity, future orientation, social capital, and self-efficacy may help create culturally appropriate interventions to improve the health and mental health of Black youth [2, 4, 9, 70, 71].

Limitations

It is important to consider the limitations of this study. First, the cross-sectional approach limits establishing temporal ordering and causality of the suicidal behavior of Black youth. Accordingly, longitudinal studies help inform whether parental communication increases suicidal behavior and if there is a reciprocal relationship over time for Black youth that ideate or make suicide attempts and talk about them with their parents and/or peers. It is also important to acknowledge that the first wave of the data for this study was captured during the 1994–1995 school year. Although there have been numerous changes in the lives of Black Americans that could have influenced suicide rates, including the recession of 2008–2010, the trauma of witnessing the death of young Black people by the aggressive use of force by law enforcement officials, the birth of the Black Lives Matter movement, exposure to violence, traumatic stress, and aggressive treatment in schools, and most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic, it has not been demonstrated, if any of these factors are related to increasing suicide rates of Black youth [1]. A study of national mortality data with similar periods from 1993 to 1997 and 2008 to 2012 suggested the overall suicide rate increased significantly in Black children aged five to 11 years but remained stable for their White counterparts [1,2,3]. Although the data were collected in the early 1990s and 2000s, we recognize time as a limitation of this study. Since the data was collected, there have not been major advancements in suicide prevention and intervention, programs and treatments, and potential parental/family interactions for Black youth, so one could argue that the data allowed us to investigate the correlates of suicidal behavior in a population that is both underserved and understudied. Investigating suicide among Black youth is critical, given the current spike in their suicide rates [2]. Considering the lack of economic mobility since the 1990s for Black people in the USA and the persisting systemic inequalities, these findings appear to be still relevant today [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74].

Further, previous research studies have established that although the CES-D has been used and normed with Black youth, there are measurement inconsistencies in its reflection of their depression symptoms, which is a limitation. Moreover, Lu et al. [54] noted that Black youth were more likely to report somatization when they are sad or feeling down versus tearfulness so future research should consider mixed method studies that prioritize the qualitative data strand in an exploratory sequential design that could result in a new depression measure for Black youth. In addition, there is inconsistency in reporting periods for recall regarding suicidal behavior versus asking about a specific timeframe, that is, the last 30 days, etc. Moreover, the uncertainty of whom the youth disclosed their suicidal behavior to is also a limitation. Future research should survey youth directly using multi and/or mixed methods to further explore the factors included in this study.

Another limitation of this study is the absence of analyses that include results for Black male and female populations. For example, it would have been ideal to examine both ideations and attempts by gender; however, the sub-samples of each were too small and had to be combined. Additionally, the parental support variable comprised units for fathers and mothers. Consequently, having more exact measures for the sample and variables would have been useful. Moreover, our results may not be generalizable to other youth because this sample only comprises Black youth. Yet, the increase in the numbers of Black youth engaging in suicidal behavior warrants this heightened focus and empirical investigation. Future studies are needed to further explore the influence of families and peers on youth and young adults’ suicidal behavior. Approaches are needed that account for variation in racial and gender identities and integrate the interaction of gender and race to address racial disparities, which all require further investigation. Therefore, future work should include samples with Black parent–child dyads in geographical locations where they reside in larger metropolitan areas to alleviate these limitations.

Implications for research and practice

This study contributes to understanding how parental support affects suicidal ideations and attempts of Black youth. Our study findings inform the literature on Black families and suicide prevention by showing that parental support may be a vehicle to reducing youth suicidal behavior. Notably, we utilized the ecodevelopmental theory to highlight the family context and its impact on whether Black youth will engage in suicidal behavior, as well as the influence of related peers who may have attempted suicide in the past. Practitioners can help support and strengthen relationships between families and their children by providing services. For instance, practitioners can provide psycho-social training for family members to identify warning signs of suicidal behavior and provide support to the youth. Practitioners can also teach families coping and problem-solving skills to prevent suicidal behaviors or intervene when a youth engages in suicidal behavior. Researchers and practitioners should also consider developing family-centered interventions with a focus on healing. When engaging with African American families and their children, researchers and practitioners should also consider examining bidirectional relationships between parents and their children. It is important to examine if there is a history of depression because there can potentially be a linked to suicidal behavior which would be important for assessment screening and treatment purposes. Interventions often focus on the individual, in this case, Black youth, who are understudied but experiencing a surge in suicide rates. As a result, it is now time not only to think about risk factors that can be modified but also the protective factors that can be strengthened and reinforced to improve the health equity of Black youth and their families.

References

Bridge JA, Asti L, Horowitz L, Greenhouse J, Fontanella C, Sheftall A, et al. Suicide trends among elementary school-aged children in the United States from 1993 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(7):673–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0465.

Lindsey, M. A., Sheftall, A. H., Xiao, Y., & Joe, S. (2019). Trends of Suicidal Behaviors Among High School Students in the United States: 1991-2017. Pediatrics, 144(5), e20191187. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-1187.

Curtin SC. State suicide rates among adolescents and young adults aged 10–24: United States, 2000–2018. (National Vital Statistics Reports, 69, 11). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr69/nvsr-69-11-508.pdf

Chetty R, Hendren N, Jones MR, Porter SR. Race and economic opportunity in the United States: an intergenerational perspective. Q J Econ. 2020;135(2):711–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjz042.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development : experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Szapocznik, J., & Coatsworth, J. D. (1999). An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection. In M. D. Glantz & C. R. Hartel (Eds.), Drug abuse: Origins & interventions (pp. 331–366). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10341-014

Nathanson M, Baird A, Jemail J. Family functioning and the adolescent mother: a systems approach. Adolescence. 1986;21:827–41 Retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3825665/.

Harrison L. Redefining intersectionality theory through the lens of African American young adolescent girls’ racialized experiences. Youth Soc. 2017;49(8):1023–39.

Quinn CR, Beer OWJ, Boyd DT, Tirmazi T, Nebbitt V, Joe S. An Assessment of the Role of Parental Incarceration and Substance Misuse in Suicidal Planning of African American Youth and Young Adults. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01045-0.

Constantine MG. Perceived family conflict, parental attachment, and depression in African American female adolescents. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2006;12(4):697–709. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.12.4.697.

Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(7):617–26. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617.

Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE Jr. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):575–600.

Hall DM, Cassidy EF, Stevenson HC. Acting “tough” in a “tough” world: an examination of fear among urban African American adolescents. J Black Psychol. 2008;34(3):381–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798408314140.

Holt MK, Espelage DL. Social support as a moderator between dating violence victimization and depression/anxiety among African American and Caucasian adolescents. Sch Psychol Rev. 2005;34:309–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2005.12086289.

Hollingsworth DW, Wingate LR, Tucker RP, O’Keefe VM, Cole AB. Hope as a moderator of the relationship between interpersonal predictors of suicide and suicidal thinking in African Americans. J Black Psychol. 2016;42(2):175–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798414563748.

Morrison KS, Hopkins R. Cultural identity, africultural coping strategies, and depression as predictors of suicidal ideations and attempts among African American female college students. J Black Psychol. 2019;45(1):3–25. Retrieved from:. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798418813511.

Spann M, Molock SD, Barksdale C, Matlin S, Puri R. Suicide and African American teenagers: risk factors and coping mechanisms. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2006;36(5):553–68. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2006.36.5.553.

Walker RL, Lester D, Joe S. Lay theories of suicide: an examination of culturally relevant suicide beliefs and attributions among African Americans and European Americans. J Black Psychol. 2006;32(3):320–34. Retrieved from:. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798406290467.

Joe S, Niedermeier D. Preventing suicide: a neglected social work research agenda. Br J Soc Work. 2006;38(3):507–30.

Walker RL, Wingate LR, Obasi EM, Joiner TE. An empirical investigation of acculturative stress and ethnic identity as moderators for depression and suicidal ideation in college students. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2008;14(1):75–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.14.1.75.

Walker RL, Salami TK, Carter SE, Flowers K. Perceived racism and suicide ideation: mediating role of depression but moderating role of religiosity among African American adults. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(5):548–59. Retrieved from:. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12089.

Kaslow NJ, Thompson MP, Okun A, Price A, Young S, Bender M, et al. Risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior in abused African American women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(2):311–9. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.311.

Matlin SL, Molock SD, Tebes JK. Suicidality and depression among African American adolescents: the role of family and peer support and community connectedness. Am J Orthop. 2011;81(1):108–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01078.x.

Nisbet PA. Protective factors for suicidal black females. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1996;26(4):325–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.1996.tb00836.x.

Thomas AL, Brausch AM. Family and peer support moderates the relationship between distress tolerance and suicide risk in black college students. J Am Coll Health. 2020 Jul 15:1-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1786096.

Joe S, Scott ML, Banks A. What works for adolescent black males at risk of suicide: a review. Res Soc Work Pract. 2018;28(3):340–5.

Perkins DF, Hartless G. An ecological risk-factor examination of suicide ideation and behavior of adolescents. J Adolesc Res. 2002;17(1):3–26. Retrieved from:. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558402171001.

Sheftall AH, Mathias CW, Furr RM, Dougherty DM. Adolescent attachment security, family functioning, and suicide attempts. Attach Hum Dev. 2013;15(4):368–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2013.782649.

Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Joe S. Suicide, negative interaction and emotional support among black Americans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(12):1947–58.

Kim YJ, Quinn CR, Moon SS. Buffering effects of social support and parental monitoring on suicide. Health Soc Work. 2021;46:42–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlaa037.

McKinnon B, Gariépy G, Sentenac M, Elgar FJ. Adolescent suicidal behaviours in 32 low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(5):340–350F. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.15.163295.

Winterrowd E, Canetto SS, Chavez EL. Friendship factors and suicidality: common and unique patterns in Mexican American and European American youth. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2011;41(1):50–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2010.00001.x.

Winterrowd E, Canetto SS. The long-lasting impact of adolescents’ deviant friends on suicidality: a 3-year follow-up perspective. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(2):245–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0529-2.

Tuisku V, Kiviruusu O, Pelkonen M, Karlsson L, Strandholm T, Marttunen M. Depressed adolescents as young adults—predictors of suicide attempt and non-suicidal self-injury during an 8-year follow-up. J Affect Disord. 2014;152–154:313–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.09.031.

Bearman PS, Moody J. Suicide and friendships among American adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(1):89–95. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.1.89.

Kerr DCR, Preuss LJ, King CA. Suicidal adolescents’ social support from family and peers: Gender-specific associations with psychopathology. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2006;34:103–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-005-9005-8.

Lindsey MA, Joe S, Nebbitt V. Family matters: the role of mental health stigma and social support on depressive symptoms and subsequent help seeking among African American boys. J Black Psychol. 2010;36(4):458–82. Retrieved from:. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798409355796.

Washington T, Rose T, Coard SI, Patton DU, Young S, Giles S, et al. Family-level factors, depression, and anxiety among African American children: a systematic review. Child Youth Care Forum. 2017;46(1):137–56. Retrieved from:. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-016-9372-z.

Zimmerman MA, Ramirez-Valles J, Zapert KM, Maton KI. A longitudinal study of stress-buffering effects for urban African American male adolescent problem behaviors and mental health. J Commun Psychol. 2000;28:17–33 https:/.

Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: results from the National comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(3):300–10. https://doi.org/10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55.

Turecki G, Brent DA. Suicide and suicidal behaviour. Lancet. 2016;387(10024):1227–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00234-2.

Harris KM. The add health study: design and accomplishments. Chapel Hill: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2013. p. 1–22.

Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278(10):823–32 10.1001.

LeCloux M, Maramaldi P, Thomas K, Wharff E. Family support and mental health service use among suicidal adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(8):2597–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0417-6.

Boyd DT, Quinn CR, Aquino GA. The inescapable effects of parent support on Black males and HIV testing. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7:563–70.

Jensen TM, Harris KM. Stepfamily relationship quality and stepchildren’s depression in adolescence and adulthood. Emerging Adulthood. 2017;5(3):191–203.

Mo Y, Singh K. Parents’ relationships and involvement: effects on students’ school engagement and performance. RMLE Online. 2008;31(10):1–11.

Hope EC, Pender KN, Riddick KN. Development and validation of the Black community activism orientation scale. J Black Psychol. 2019;45(3):185–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798419865416.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401.

Foley KL, Reed PS, Mutran EJ, DeVellis RF. Measurement adequacy of the CES-D among a sample of older African–Americans. Psychiatry Res. 2002;109(1):61–9.

Sharp LK, Lipsky MS. Screening for depression across the lifespan: a review of measures for use in primary care settings. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(6):1001–8.

Zich JM, Attkisson CC, Greenfield TK. Screening for depression in primary care clinics: the CES-D and the BDI. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1990;20(3):259–77.

Weissman MM, Wolk S, Goldstein RB, Moreau D, Adams P, Greenwald S, et al. Depressed adolescents grown up. JAMA. 1999;281:1707–13. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.18.1707.

Lu W, Lindsey MA, Irsheid S, Nebbitt VE. Psychometric properties of the CES-D among Black adolescents in public housing. J Soc Soc Work Res. 2017;8(4):595–619.

Leong FT, Austin JT. The psychology research handbook: a guide for graduate students and research assistants. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2005.

Starkweather J, Moske AK. Multinomial logistic regression; 2011

Mckeown RE, Garrison CZ, Cuffe SP, Waller JL, Jackson KL, Addy CL. Incidence and predictors of suicidal behaviors in a longitudinal sample of young adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(6):612–9.

Boyd D, Lea CH III, Gilbert KL, Butler-Barnes ST. Sexual health conversations: predicting the odds of HIV testing among Black youth and young adults. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;90:134–40.

O'Donnell L, Stueve A, Wardlaw D, O'Donnell C. Adolescent suicidality and adult support: the reach for health study of urban youth. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(6):633–44.

Infante DA. Corporal punishment of children: a communication-theory perspective. In: Donnelly M, Straus MA, editors. Corporal punishment of children in theoretical perspective. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2005. p. 183–98.

Wimsatt AR, Fite PJ, Grassetti SN, Rathert JL. Positive communication moderates the relationship between corporal punishment and child depressive symptoms. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2013;18(4):225–30.

Holt MK, Espelage DL. Social support as a moderator between dating violence victimization and depression/anxiety among African American and Caucasian adolescents. Sch Psychol Rev. 2005;34(3):309–28.

Quinn CR, Beer OWJ, Boyd DT, Tirmazi T, Nebbitt V, Joe S. An Assessment of the Role of Parental Incarceration and Substance Misuse in Suicidal Planning of African American Youth and Young Adults. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01045-0.

Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(3–4):372–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x.

Mueller AS, Abrutyn S. Suicidal disclosures among friends: using social network data to understand suicide contagion. J Health Soc Behav. 2015;56(1):131–48.

Johnson JG, Cohen P, Gould MS, Kasen S, Brown J, Brook JS. Childhood adversities, interpersonal difficulties, and risk for suicide attempts during late adolescence and early adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(8):741–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.741.

Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Spirito A, Little TD, Grapentine WL. Peer functioning, family dysfunction, and psychological symptoms in a risk factor model for adolescent inpatients’ suicidal ideation severity. J Clin Child Psychol. 2000;29(3):392–405. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP2903_10.

McLoyd VC, Kaplan R, Hardaway CR, Wood D. Does endorsement of physical discipline matter? Assessing moderating influences on the maternal and child psychological correlates of physical discipline in African American families. J Fam Psychol. 2007;21(2):165–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.165.

Gould MS, Greenberg TED, Velting DM, Shaffer D. Youth suicide risk and preventive interventions: A review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(4):386–405.

Fitzpatrick KM, Piko BF, Wright DR, LaGory M. Depressive symptomatology, exposure to violence, and the role of social capital among African American adolescents. Am J Orthop. 2005;75(2):262–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.262.

Quinn, C. R., Boyd, D. T., Kim, B. K. E., Menon, S. E., Logan-Greene, P., Asemota, E., Diclemente, R. J., & Voisin, D. (2021). The Influence of Familial and Peer Social Support on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Among Black Girls in Juvenile Correctional Facilities. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 48(7), 867-883. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854820972731.

O’Donnell L, Stueve A, Wardlaw D, O’Donnell C. Adolescent suicidality and adult support: the reach for health study of urban youth. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(6):633–44. https://doi.org/10.5993/ajhb.27.6.6.

Taliaferro LA, Muehlenkamp JJ. Risk and protective factors that distinguish adolescents who attempt suicide from those who only consider suicide in the past year. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(1):6–22. Retrieved from:. https://doi.org/10.1037/10341-014Taliaferro.

Lofton R, Davis JE. Toward a Black habitus: African Americans navigating systemic inequalities within home, school, and community. J Negro Educ. 2015;84(3):214–30.

Data and materials availability

The data and materials for this study support our empirical claims and comply with field standards.

Code availability

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Camille R. Quinn and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boyd, D.T., Quinn, C.R., Jones, K.V. et al. Suicidal ideations and Attempts Within the Family Context: The Role of Parent Support, Bonding, and Peer Experiences with Suicidal Behaviors. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 9, 1740–1749 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01111-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01111-7