Abstract

Background

African-Americans and Hispanics receive disproportionately less aggressive non-critical treatment for chronic diseases than their Caucasian counterparts. However, when it comes to end-of-life care, minority races are purportedly treated more aggressively in Medical Intensive Care Units (MICU) and are more likely to die there.

Objective

We sought to determine the impact of race on the intensity of care provided to older adults in the Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU) using the Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System-28 (TISS-28) and other MICU interventions.

Methods

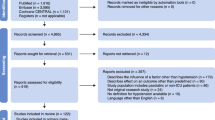

This is a prospective study of a cohort of 309 patients aged 60 years and older in the MICU. Interventions such as mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, new onset dialysis, feeding tubes, and pulmonary artery catheterization were recorded. Primary outcomes were TISS-28 scores and MICU interventions.

Results

Non-white patients were younger and had more dementia and delirium although there was no difference in ICU mortality. The amount of critical care delivered to non-white and white patients were equivalent at p ≤ 0.05 based on their respective TISS-28 scores. Non-white patients received more renal replacement therapy than white patients.

Conclusions

Our study adds to the growing body of literature demonstrating that the relationship between race, patient preference, and the intensity of care provided in MICUs is multifaceted. Although prior studies have reported that non-white populations often opt for more aggressive care, the similar proportions of non-white and white “full code” patients in this study suggests that this idea is overly simplistic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of Daily Living Scale

- APACHE II:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- CCI:

-

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- COPD:

-

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- IQCODE:

-

Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly

- IADL:

-

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale

- MICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- SAPS:

-

Simplified Acute Physiology Score

- TISS-28:

-

Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System-28

- YNHH:

-

Yale-New Haven Hospital

References

Bureau USC. U.S. Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. 2012. https://http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12-243.html. Accessed 6/29/2013 2013.

Nelson A Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(8):666–8.

Athamneh LN, Sansgiry SS. Influenza vaccination in patients with diabetes: disparities in prevalence between African Americans and Whites. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2014;12(2):410.

LaVeist TA, Morgan A, Arthur M, Plantholt S, Rubinstein M. Physician referral patterns and race differences in receipt of coronary angiography. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(4):949–62.

Chen J, Rathore SS, Radford MJ, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. Racial differences in the use of cardiac catheterization after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(19):1443–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM200105103441906.

Mayr FB, Yende S, D’Angelo G, Barnato AE, Kellum JA, Weissfeld L, et al. Do hospitals provide lower quality of care to black patients for pneumonia? Crit Care Med. 2010;38(3):759–65. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c8fd58.

Mayberry RM, Mili F, Ofili E. Racial and ethnic differences in access to medical care. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 1):108–45.

Liao Y, Bang D, Cosgrove S, Dulin R, Harris Z, Taylor A, et al. Surveillance of health status in minority communities—racial and ethnic approaches to community health across the U.S. (REACH U.S.) risk factor survey, United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(6):1–44.

Muni S, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, Dotolo D, Curtis JR. The influence of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on end-of-life care in the ICU. Chest. 2011;139(5):1025–33. doi:10.1378/chest.10-3011.

Barnato AE, Chang CC, Saynina O, Garber AM. Influence of race on inpatient treatment intensity at the end of life. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(3):338–45. doi:10.1007/s11606-006-0088-x.

Nayar P, Qiu F, Watanabe-Galloway S, Boilesen E, Wang H, Lander L, et al. Disparities in end of life care for elderly lung cancer patients. J Community Health. 2014. doi:10.1007/s10900-014-9850-x.

Barnato AE, Alexander SL, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC. Racial variation in the incidence, care, and outcomes of severe sepsis: analysis of population, patient, and hospital characteristics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(3):279–84. doi:10.1164/rccm.200703-480OC.

Miranda DR, de Rijk A, Schaufeli W. Simplified therapeutic intervention scoring system: the TISS-28 items–results from a multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 1996;24(1):64–73.

Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 2: health outcomes and satisfaction with care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):288–98.

Barnato AE, Chang CC, Farrell MH, Lave JR, Roberts MS, Angus DC. Is survival better at hospitals with higher "end-of-life" treatment intensity? Med Care. 2010;48(2):125–32. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c161e4.

Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):273–87.

Pisani MA, Inouye SK, McNicoll L, Redlich CA. Screening for preexisting cognitive impairment in older intensive care unit patients: use of proxy assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5):689–93.

Jorm AF. A short form of the informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (IQCODE): development and cross-validation. Psychol Med. 1994;24(1):145–53.

Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of adl: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–9.

Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–86.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–29.

Wellek S Testing statistical hypotheses of equivalence. Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, Fla; 2003.

I SI. SAS User’s Manual. Version 9.3. Cary, N.C2009.

Quill CM, Ratcliffe SJ, Harhay MO, Halpern SD. Variation in decisions to forgo life-sustaining therapies in US intensive care units. Chest. 2014. doi:10.1378/chest.13-2529.

Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Paulk E, DeSanto-Madeya S, Nilsson M, Viswanath K, et al. Racial differences in predictors of intensive end-of-life care in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(33):5559–64. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4733.

Collins N, Blanchard MR, Tookman A, Sampson EL. Detection of delirium in the acute hospital. Age Ageing. 2010;39(1):131–5. doi:10.1093/ageing/afp201.

Campbell NL, Cantor BB, Hui SL, Perkins A, Khan BA, Farber MO, et al. Race and documentation of cognitive impairment in hospitalized older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(3):506–11. doi:10.1111/jgs.12691.

Boustani M, Baker MS, Campbell N, Munger S, Hui SL, Castelluccio P, et al. Impact and recognition of cognitive impairment among hospitalized elders. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(2):69–75. doi:10.1002/jhm.589.

Tang S, Patel P, Khubchandani J, Grossberg GT. The psychogeriatric patient in the emergency room: focus on management and disposition. ISRN Psychiatry. 2014;2014:413572. doi:10.1155/2014/413572.

Miesfeldt S, Murray K, Lucas L, Chang CH, Goodman D, Morden NE. Association of age, gender, and race with intensity of end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(5):548–54. doi:10.1089/jpm.2011.0310.

Diringer MN, Edwards DF, Aiyagari V, Hollingsworth H. Factors associated with withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in a neurology/neurosurgery intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(9):1792–7.

Barnato AE, Mohan D, Downs J, Bryce CL, Angus DC, Arnold RM. A randomized trial of the effect of patient race on physicians’ intensive care unit and life-sustaining treatment decisions for an acutely unstable elder with end-stage cancer. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(7):1663–9. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182186e98.

Murphy ST, Palmer JM, Azen S, Frank G, Michel V, Blackhall LJ. Ethnicity and advance care directives. J Law Med Ethics. 1996;24(2):108–17.

Kwak J, Haley WE. Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist. 2005;45(5):634–41.

Borum ML, Lynn J, Zhong Z. The effects of patient race on outcomes in seriously ill patients in SUPPORT: an overview of economic impact, medical intervention, and end-of-life decisions. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 Suppl):S194–8.

Mack JW, Paulk ME, Viswanath K, Prigerson HG. Racial disparities in the outcomes of communication on medical care received near death. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(17):1533–40. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.322.

Welch LC, Teno JM, Mor V. End-of-life care in black and white: race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1145–53. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53357.x.

Paola FA. The case of Jahi McMath: professionalism and knowing one’s limitations. J Physician Assist Educ. 2014;25(1):59–61.

Padilha KG, Sousa RM, Kimura M, Miyadahira AM, da Cruz DA, Vattimo Mde F, et al. Nursing workload in intensive care units: a study using the therapeutic intervention scoring system-28 (TISS-28). Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2007;23(3):162–9. doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2006.07.004.

Acknowledgments

Guarantor Statement

C.Chima-Melton takes responsibility for the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis.

Author Contributions

C.Chima-Melton formulated the research question, conducted the background research and prepared the paper. K. L. B. Araujo managed the data and prepared figures and tables for the paper. T. E. Murphy performed the necessary statistical research and statistical analysis for this paper. M. Pisani enrolled patients and collected the data for this study. In addition, M. Pisani mentored C.Chima-Melton for study design and paper preparation.

Financial/Nonfinancial Disclosures

M. Pisani is a recipient of a NIH K23 Mentored Career Development Award (K23 AG 23023-01A1) and the Chest Foundation and Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Clinical Research Award in Women’s Pulmonary Health. T. E. Murphy was supported in part by Grants from the Biostatistics Core of the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University School of Medicine (no. 2P30AG021342-06).

Funding Information

M. Pisani is a recipient of a NIH K23 Mentored Career Development Award (K23 AG 23023-01A1) and the Chest Foundation and Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Clinical Research Award in Women’s Pulmonary Health. T. E. Murphy was supported in part by Grants from the Biostatistics Core of the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University School of Medicine (no. 2P30AG021342-06).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Key Messages

• Non-white patients received more renal replacement therapies than their white counterparts. We did not detect any other race-based differences in rates of MICU interventions or intensity of care as measured by the TISS-28 score with respect to most aspects of critical care.

• Multivariable analysis delineated the lack of association seen between race and TISS-28 whereas other variables, such as higher BMI, delirium, and intubation, showed a positive correlation with TISS-28 scores.

• In our population of critically ill older adults, despite being significantly younger, non-white patients had similar mortality rates to white patients.

• Our study demonstrates that non-white patients had higher baseline rates of dementia and greater rates of ICU delirium.

• This work adds to the growing body of literature demonstrating that the relationship between race and intensity of care provided is multifaceted, complicated, and cannot be easily generalized.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chima-Melton, C., Murphy, T.E., Araujo, K.L.B. et al. The Impact of Race on Intensity of Care Provided to Older Adults in the Medical Intensive Care Unit. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 3, 365–372 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0162-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0162-3