Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to determine (a) whether the use of short message service (SMS) appointment reminders is an acceptable form of communication about colonoscopy appointments and (b) whether the use of SMS appointment reminders is as efficacious as the use of telephone reminders calls for colonoscopy completion.

Methods

Patients referred by a primary care physician for a screening colonoscopy (N = 24) were recruited to participate over a 10-month period. Eligible participants (i.e., owned a cell phone and agreed to receive text reminders) were randomized to receive either usual care (N = 13) or SMS reminders (N = 11). Participants were given 3 months to complete the exam followed by analysis of colonoscopy completion status.

Results

In the non-SMS group, 46.2 % participants completed a colonoscopy compared to 72.7 % of participants in the SMS group (p = 0.19).

Conclusions

SMS has potential to be an efficacious approach for use within patient navigation interventions for screening colonoscopy and that using SMS reminders for colonoscopy patient navigation interventions should be replicated in a randomized clinical trial, with a larger sample size.

Similar content being viewed by others

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a leading cause of cancer death among African-Americans and Hispanics [1]. This is unfortunate given that endoscopic screening can actually prevent CRC [2] through the detection and simultaneous removal of adenomatous polyps. Lack of participation in CRC screening contributes to greater incidence of advanced-stage CRC diagnosis, when treatment options are more limited. Unfortunately, African-Americans and Hispanics are less likely to participate in CRC screening (i.e., screening colonoscopy [SC]) than Whites [1]. Lack of CRC screening is one reason for higher CRC mortality rates among African-Americans and Hispanics [1, 3, 4] and interventions are needed to improve this population’s SC rates in order to ameliorate these disparities.

In general, patient navigation (PN) [5] seeks to reduce cancer disparities by addressing barriers that medically underserved populations (racial/ethnic minorities, low-income persons, immigrants, uninsured, etc.) often encounter in our health care system [6]. A patient navigator is a trained staff member within the health care setting who helps a patient move through (i.e., navigate) the health care system to obtain medical care. By tradition, patient navigation programs have assisted cancer patients in obtaining follow-up of suspicious findings and treatment. More recently, patient navigation has expanded to include cancer screening [7] and is focused on scheduling and reminding patients of their appointments and educating them about the preparation, the procedure itself, and other logistics (i.e., needing an escort). PN affects low rates of CRC screening among racial and ethnic minorities [8, 9] by effectively addressing several multilevel ecological barriers to SC [10], including intrapersonal-level barriers (fear of pain, fear of diagnosis, fatalism, ignorance about CRC screening), interpersonal-level barriers (lack of social support, physician-patient communication), and community-level barriers (lack of transportation/escort, care-taking responsibilities, and conflicts with work schedules). Although PN interventions are effective, they can also be costly in terms of the number of hours spent contacting patients (e.g., reminder calls).

Disparities in the access of digital information and communications technologies has come to be referred to as the “digital divide” between those who have access to information technologies and those who do not [11–13]. There is no consensus on the extent, impact, or causes of the digital divide; however, various contributing factors have been identified including low socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity, and living in rural settings, among others [11–13]. The use of technology among diverse racial and ethnic groups has tended to focus on the digital divide and disproportionately low computer and Internet access and use among certain groups, including health-related use.

Mobile health (mHealth) technology, one form of information and communication technology, is changing the way health care access and delivery is approached. Short message service (SMS) or text messages allow users to send and receive text messages on mobile devices (e.g., cellular phones). Each message is up to 160 characters in length. Text messages can be sent quickly and are relatively low cost. Mobile devices are an exception to the digital divide. Due to technological advances, many people are accessing the internet and communicating through cellular phones. Recent evidence suggests that the divide is narrowing in this respect, especially when mobile devices are considered. Minorities, particularly African-Americans and Hispanics, are more likely to use SMS features on their mobile phones than their white counterparts [14]. For example, African-Americans are more likely to receive health information via text messages [15].

Mobile technology has the potential to provide outreach and access to people regardless of socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, or location. Despite the ubiquity of mobile phones, increased attention must be focused on technology that accommodates low literacy and non-English languages to avoid promotion of a digital divide and widening health disparities [16]. For example, researchers need to consider that for many individuals, especially those from low-income backgrounds, cellular plans may not provide SMS as a component of base rates for mobile plans [17]. Furthermore, while mHealth technologies have the potential to improve population health outcomes, the use of SMS still requires a certain level of literacy. Researchers should also consider how the elderly or individuals without advanced technical skills evaluate SMS reminders or participate in the mHealth interventions.

The use of automated SMS reminders may be a more cost-effective approach to PN, but it is unknown whether using this technology in conjunction with PN is efficacious in African-American and Hispanic, low-income, older adult populations. To date, there are no published studies that explore the use of SMS within a comprehensive screening PN program. SMS reminders, however, have been shown to have similar effectiveness as an intervention tool for medical appointment reminders as telephone reminders in terms of their effect on appointment attendance rates [18]. Examples include reminders for adult patients [19] and parents of pediatric patients [20] in outpatient clinic settings and various behavioral health interventions, including smoking cessation [21] and breast self-examination [22]. Overall, these studies suggest that SMS reminders increase adherence to medical recommendations. Another benefit of using SMS reminders is that they are less costly than telephone reminders [18]. The results from studies comparing the effectiveness of SMS reminders and telephone reminders is low to moderate and more information and research is needed about SMS reminders before making conclusions about clinical practice and policy.

These findings, however, are also promising for the development of interventions using mobile technology with minorities and older adults considering that rates of cell phone use have increased dramatically over the past few years, especially among low-income and racial and ethnic minority populations [14]. Moreover, approximately 58 % of adults 50–64 years use their cell phones to send or receive SMS [14], and rates of SMS are increasing within this age group [14] and beyond [23], which indicates that older adults are capable of and willing to use SMS. As health professionals begin to increasingly use this mobile technology to communicate with patients, it will be important to assess the initial efficacy of using SMS reminders in health interventions, especially among low-income, racial and ethnic minorities, and older adults (over age 50). It will also be important to understand which contexts and subpopulations are best suited for the use of SMS reminders. Thus, the objective of this study was to determine the efficacy of SMS as reminders for SC completion and to conduct a power analysis to guide future randomized clinical trials (RCT).

Methods

Participants

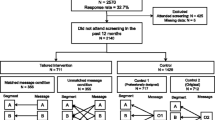

African-American and Hispanic participants (N = 24) that were eligible (over 50 years, received a physician referral for a SC only [i.e., those referred for diagnostic colonoscopy were not eligible], no personal history of CRC or any chronic gastrointestinal disorder [verified by chart review], or family history of CRC, had telephone service, and spoke English) were recruited for the current study. Participants were recruited at an internal medicine clinic serving low-income, publicly (i.e., Medicaid and/or Medicare) and privately insured patients at an academic hospital in Upper Manhattan, New York. Over a 10-month period (2011–2012) participants were enrolled in this IRB-approved study. In order to be eligible for the study, participants were asked whether they (a) owned a cell phone and (b) were willing to receive SMS reminders for their SC appointment.

Procedure

After being consented, all participants received a telephone call from a patient navigator (each participant was randomly assigned to one of eight patient navigators, depending on the navigator’s current workload). A patient navigator is a professionally trained health educator who assists patients through the colonoscopy appointment process including scheduling and review of prep instructions. The patient navigator explained and reviewed the SC procedure and scheduled the participants’ appointments.

All participants had to speak to a patient navigator over the phone in order to receive an appointment for their SC. The patient navigators attempted to contact all participants, in both study arms, by telephone for the scheduling phone call. The initial phone call was a scheduling call in which information about the SC procedure was described and the colonoscopy appointment was given. If a participant was not able to be reached by telephone, a voicemail was left informing the participant that someone from the hospital would call again to schedule an appointment. If a voicemail was not returned or the participant was unable to be reached over the phone after making at least four phone calls to schedule an appointment, the patient navigator mailed a letter informing the participant to call to schedule their appointment. If the patient navigator did not hear back from a participant, the participant was excluded from the study and was not randomized to an intervention group.

On average, participants were given an appointment within 4–6 weeks of the initial referral for a SC from their physician. Participants scheduled for a colonoscopy were then randomly assigned to one of two groups: (1) standard navigation (non-SMS, N = 13) or (2) navigation with SMS reminders (SMS, N = 11). After the initial scheduling phone call, a reminder contact either by telephone or SMS was delivered 2 weeks before the scheduled colonoscopy appointment and another reminder contact was delivered 3 days before the appointment. Participants were paid $10 for completing a short survey and to offset the cost of any text messages they received and/or sent (only applicable for SMS participants).

Non-SMS Group

In the non-SMS group, participants were navigated by a trained patient navigator and received two personal appointment reminders via telephone calls. On these two reminder calls, the patient navigator explained the SC preparation (e.g., how to take the laxative) and answered any questions the patient had about the procedure or their appointment.

SMS Group

Participants in the SMS group received standard navigation from the same PN but instead of two personal telephone-based reminder calls, they received the initial scheduling telephone call and two appointment reminders via SMS. Participants in the SMS group received the same automated SMS message (via Google Voice) asking whether they received instructions for the SC (i.e., laxative prep) and to confirm whether they received the SMS reminder (see Table 1 for sample text). The SMS message was developed to address the key components addressed in standard navigation procedures (see above). Participants in the SMS group were directed to call their navigator if they had any questions.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity) were measured via the patient’s medical record. The main outcome measure was SC completion, which was retrieved from the patient’s medical record following their scheduled appointment date.

Analysis

Although 30 participants were recruited, consented, and enrolled, only 24 were scheduled for an appointment and thus included in analysis. Because we were most interested in the clinical application of SMS reminders for SC appointment reminders, we conducted an intent-to-treat analysis of the sample. In this analysis, we include participants, from both arms, who were not reached for reminder navigation contacts (i.e., no confirmation of receipt of SMS and did not return a voicemail for reminder phone calls). There could be numerous reasons for unresponsiveness for any given participant in this study and this fact underscores the importance of conducting intent-to-treat analyses. Intent-to-treat analysis includes all randomized participants in the group assigned, regardless of adherence, actual receipt of the intervention, or withdrawal from the intervention [24]. Intent-to-treat analyses acknowledge and account for noncompliance, which is often assumed to occur with participants who are unable to be contacted. Descriptive analyses (Chi-square) were conducted to describe the demographic characteristics of the overall sample and the randomization groups (SMS vs. non-SMS). A post hoc power analysis using G Power (a free online power analysis calculator; [25]) was conducted to estimate the sample size for a larger RCT.

Results

Overall, the average age of participants in this study was 55.29 (SD = 5.23) and the majority of participants were female (83.3 %, n = 20). Half (52.4 %, n = 11) of the participants identified themselves as African-American, and 47.6 % (n = 10) of participants identified as Hispanic. Overall, 58.3 % (n = 14) of the sample completed a SC (see Table 2). Participants who did not complete a colonoscopy did not show up for their appointments.

The two randomization groups (SMS vs. Non-SMS) were not statistically different in terms of age, gender, race/ethnicity, or insurance type. In the SMS group, 50.0 % (n = 5) of participants were Hispanic and 50.0 % (n = 5) of the participants were African-American. In the non-SMS group, 54.5 % (n = 6) of participants were African-American and 45.5 % (n = 5) were Hispanic.

Five participants (41.7 %) in the SMS group responded to the first reminder text (see Fig. 1) and only four participants (36.4 %) confirmed receipt of the second reminder text. All but one of the participants in the SMS group who confirmed receipt of the text completed the colonoscopy compared to all but one participant who did not confirm and did not complete the colonoscopy. In the non-SMS group, three participants (20.0 %) were reached the first time a scheduling phone call was made, thus requiring additional telephone calls. Among participants who were scheduled for a colonoscopy appointment (i.e., completed the scheduling phone call) in the non-SMS group, 53.8 % (n = 7) were reached by phone for the first reminder call. For the second reminder call, 61.5 % (n = 8) was reached by phone (See Fig. 2). A voicemail message was left for 61.5 % (n = 8) of participants for the first reminder call; voicemail messages were left for 33.3 % (n = 3) of participants for the second reminder call. At least one voicemail message was left for 80 % (n = 12) of participants in the non-SMS group.

Only 46.2 % (n = 6) of participants in the non-SMS group completed a SC compared to 72.7 % (n = 8) of participants in the SMS group (see Table 2). There was not a statistically significant difference in the completion rates between the two groups (p = 0.19). Based on these results, power calculations indicated that a larger sample size (N = 179) would have resulted in statistical significance.

Overall, of the 14 participants who completed a colonoscopy, 23.1 % (n = 3) had fair or poor prep quality and 76.9 % (n = 10) had good or excellent prep quality (prep quality rating was missing for one participant). Prep quality between the study arms did not differ statistically (p = .49). Among participants randomized to the non-SMS group, only one participant (20 %) had a poor prep, while four participants had good or excellent prep quality (80 %). In the SMS group, two participants had poor or fair prep quality (25 %), while the other six participants had good prep quality (75 %). (see Table 2 and Fig. 3).

Discussion

More participants who were sent navigation assistance via SMS reminders completed a SC compared to participants who received standard navigation assistance. Overall, the current study’s adherence rates are comparable to the national average (66.8 %) rate of up-to-date endoscopic screening [26], but are lower than completion rates achieved with non-SMS PN in a related, parallel study [27, 28]. The current study contributes information about the efficacy of SMS appointment reminders among racially and ethnically diverse, older adult populations enrolled in a comprehensive PN intervention, which has not been explored in the literature. Based on these findings, the use of SMS reminders among participants who were recommended for SC and both owned and used a cell phone and were willing to receive text reminders is efficacious for SC appointment reminders within this specific population (i.e., over 50, African-American and/or Hispanic). This finding suggests that, with a larger sample size, using SMS reminders for SC PN interventions could be replicated in a RCT.

Although we did not report on the length of time patient navigators spent contacting participants in this study, another unpublished study (Sly et al.) reports this information. In a related study, patient navigators spent an average of 23.77 (SD = 17.22) minutes on the first reminder call and 2.89 min (SD = 1.01) on the second reminder call. In the current study, the automated reminders (initiated by the first author) took less than 1 min to send to participants. This finding demonstrates further support for the efficiency and potential cost-effectiveness of the use of SMS for appointment reminders. Related to the amount of time navigators spent contacting participants for navigation assistance is the issue of successfully reaching participants for navigation reminders. Of the participants who were scheduled for an appointment, about half (in both groups) were not able to be reached (or confirmed receipt of reminder) for the first navigation reminder, while slightly more participants were reached in non-SMS group for the second navigation reminder. Additionally, though not all patients in the SMS group responded to the SMS reminder, they did likely read the reminder messages. Patient navigators spend a considerable amount of time attempting to reach a participant to speak to them to remind them about their appointment, but with the SMS reminder navigation approach, the need to speak with a patient may only be necessary for specific questions or concerns.

Additionally, we found that colonoscopy preparation quality was similar among participants in the SMS and non-SMS groups. The impact of preparation quality on the detection of polyps during a colonoscopy is significant, particularly in terms of detection of adenomas [29], increased time to complete the examination [30], and increased hospital costs [31]. Although generalizations cannot be made from this study due the small sample size, there is evidence to suggest that, for some patients, a review of the preparation materials over the phone may not be necessary. Overall (for both non-SMS and SMS participants) suboptimal (fair or poor) preparation quality rates for the current study (23 %) were comparable to national rates (23 %) [32] as well to suboptimal preparation quality rates in a related study (Miller, Itzkowitz, Shah & Jandorf, unpublished manuscript).

This study’s results are similar to the results of other studies [18] examining the effectiveness of SMS reminders. In general, SMS reminders have been shown to be as effective as telephone reminders in health care settings and thus, it is not surprising that this study had similar results. However, the current study tested whether combining two approaches—navigation assistance and SMS reminders—would be as effective as navigation assistance via telephone calls. Because there was no difference between the two groups in this pilot, a larger trial testing the effectiveness of SMS-based navigation may provide more evidence about the effectiveness of SMS-based navigation as well as identify the subset of patients who may respond best to this type of navigation.

New Contribution to the Literature

To our knowledge, there is no literature on the efficacy of SMS reminders within the context of a PN intervention for SC. Our findings suggest that this approach could be an efficacious way of reminding patients of their upcoming appointment. The current pilot’s findings are consistent with research on the feasibility of using SMS appointment reminders for other types of interventions [19, 20]. For example, a UK study found that older rheumatology patients (up to 65-year-olds) found SMS reminders for appointment reminders acceptable and were confident in their ability to receive and read the SMS [33].

Limitations

We acknowledge five study limitations. First, the sample size was small; although as noted before, we were able to calculate the sample size needed for future studies. Second, the generalization of results may thus be inappropriate. Third, feasibility data such as the refusal rate and reasons for refusal were not systematically recorded, which limits the ability to understand who is not interested in participating in mobile technology for healthcare appointment reminders. Future studies should focus on the feasibility of text reminders for SC appointments. Qualitative research could be used to gather information from patients about the feasibility and acceptability of text reminders. Interestingly, the recruitment process took a considerable amount of time given the small sample size. This suggests that although cell phone and SMS use is increasing among older adults, there is still some apprehension about using it as a form of communication about healthcare appointments. Despite this apprehension, perceptions and attitudes toward cell phone and SMS messaging are likely to change. As people get older, they are likely to continue using their phones, which is promising for future research on the use of SMS and other mobile technology. Fourth, the overrepresentation of females in this study makes it difficult to understand how male participants might respond to SMS for health screenings. A report by the PEW Research Center found that men and women sent/received similar average of texts each day (40.9 texts for men vs. 42.0 texts for women), but that the median number of text messages sent/received by women was slightly higher (15 texts) than for men (10 texts) [14], which may explain why more females than males are represented in the current study. Future research should make more concerted efforts to recruit and enroll men, particularly African-American men, because incidence and mortality rates are higher among African-American men than African-American women [1]. Finally, data about participants’ level of fluency and proficiency with the English language were not collected which could have provided additional information about health literacy and SMS messaging. It is important to recognize patient health literacy in SMS (text-based) reminder interventions. Future studies should assess whether patients’ level of health literacy is related to the use of SMS reminders.

Future research, therefore, should attempt to replicate the findings of the current pilot in a larger RCT study. A RCT will support examination of the proportion of racial/ethnic minorities in which SMS reminders would be an appropriate intervention. The RCT should include further investigation, including qualitative approaches, of participants’ perspectives on the feasibility and acceptability of SMS reminders for SC as well as how sociocultural barriers (e.g., cell service disconnection, cost of receiving SMS) may affect the receipt of SMS reminders in low-income populations. Future studies should also assess whether patient’s level of health literacy is related to the use of SMS reminders as well as assess whether participants who responded to reminder SMS were more likely to complete the colonoscopy.

Disparities in the use of SMS use among minority population are diminishing and the use of mobile devices, particularly SMS reminders, may be associated with this decline. More research is needed, however, to encourage greater recruitment and inclusion of racial and ethnic minorities in mHealth interventions. A recent review article [15] that examined the use of new media in cancer prevention and control found that racial and ethnic diversity within new media interventions was limited (less than 20 %) in about one-fourth of the studies included in the review and another 22 % of all studies included in the review did not report any racial or ethnic information about the sample. Neglecting to recruit diverse participants to mHealth research may serve to detract from the advances made in narrowing the digital divide. The use of emerging technology in healthcare promises to increase interaction and communication between patients and healthcare providers, thus, it will be important to ensure that the digital divide is not perpetuated by adopting a “one-size-fits-all” approach to mobile technology and healthcare.

References

American Cancer Society. Colorectal cancer facts & figures 2011-2013. 2011. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-028312.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2013.

Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Smith RA, Brooks D, Andrews KS, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(3):130–60.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2009-2011. 2011. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/document/ffhispanicslatinos20092011.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2013.

American Cancer Society. Cancer prevention & early detection facts & figures 2012. 2012. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-033423.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2013.

Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. 1995;3(1):19–30.

Sly JR, Edwards T, Shelton RC, Jandorf L. Identifying barriers to colonoscopy screening for nonadherent African American participants in a patient navigation intervention. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(4):449–57.

Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, Garcia R, Greene A, Calhoun E, et al. Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer. 2008;113(8):1999–2010.

Jandorf L, Gutierrez Y, Lopez J, Christie J, Itzkowitz SH. Use of a patient navigator to increase colorectal cancer screening in an urban neighborhood health clinic. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2):216–24.

Chen LA, Santos S, Jandorf L, Christie J, Castillo A, Winkel G, et al. A program to enhance completion of screening colonoscopy among urban minorities. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(4):443–50.

McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–77.

Dewan S, Riggins FJ. The digital divide: current and future research directions. Journal of the Association for information systems. 2005;6(12).

James J. The global digital divide in the internet: developed countries constructs and third world realities. J Inf Sci. 2005;31(2):114–23.

Chang BL, Bakken S, Brown SS, Houston TK, Kreps GL, Kukafka R, et al. Bridging the digital divide: reaching vulnerable populations. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(6):448–57.

Smith A. Americans and their cell phones: mobile devices help people solve problems and stave off boredom, but create some new challenges and annoyances. Atlanta: Pew Research Center; 2011. http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media//Files/Reports/2011/Cell%20Phones%202011.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2014.

Thompson HS, Shelton RC, Mitchell J, Eaton T, Valera P, Katz A. Inclusion of underserved racial and ethnic groups in cancer intervention research using new media: a systematic literature review. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2013;2013(47):216–23.

Sarkar U, Karter AJ, Liu JY, Adler NE, Nguyen R, López A, et al. The literacy divide: health literacy and the use of an internet-based patient portal in an integrated health system—results from the diabetes study of northern California (DISTANCE). J Health Commun. 2010;15(S2):183–96.

Martin T. Assessing mHealth: opportunities and barriers to patient engagement. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(3):935–41.

Gurol-Urganci I, de Jongh T, Vodopivec-Jamsek V, Atun R, Car J. Mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at healthcare appointments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12, CD007458.

da Costa TM, Salomao PL, Martha AS, Pisa IT, Sigulem D. The impact of short message service text messages sent as appointment reminders to patients’ cell phones at outpatient clinics in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Int J Med Inform. 2010;79(1):65–70.

Kruse LV, Hansen LG, Olesen C. Non-attendance at a pediatric outpatient clinic. SMS text messaging improves attendance. Ugeskr Laeger. 2009;171(17):1372–5.

Rodgers A, Corbett T, Bramley D, Riddell T, Wills M, Lin RB, et al. Do u smoke after txt? Results of a randomised trial of smoking cessation using mobile phone text messaging. Tob Control. 2005;14(4):255–61.

Khokhar A. Short text messages (SMS) as a reminder system for making working women from Delhi breast aware. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10(2):319–22.

Gell NM, Rosenberg DE, Demiris G, Lacroix AZ, Patel KV. Patterns of technology use among older adults with and without disabilities. Gerontologist. 2013. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt166.

Gupta SK. Intention-to-treat concept: a review. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2(3):109–12.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A, Buchner A. G* power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–91.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey data. 2012. http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/list.asp?cat=CC&yr=2012&qkey=8531&state=All. Accessed March 7, 2014].

Jandorf L, Braschi C, Sly JR, Singh S, Villagra C. Increasing colonoscopy screening for Latino Americans through a patient navigation model: a randomized control trial. J Immigrant Minority Health. In press.

Jandorf L, Braschi C, Ernstoff E, Wong CR, Thelemaque LD, Winkel G, et al. Culturally targeted patient navigation for increasing African American’s adherence to screening colonoscopy: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(9):1577–87.

Lebwohl B, Kastrinos F, Glick M, Rosenbaum AJ, Wang T, Neugut AI. The impact of suboptimal bowel preparation on adenoma miss rates and the factors associated with early repeat colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(6):1207–14.

Chan W, Saravanan A, Manikam J, Goh K, Mahadeva S. Appointment waiting times and education level influence the quality of bowel preparation in adult patients undergoing colonoscopy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11(1):86.

Rex DK, Imperiale TF, Latinovich DR, Bratcher LL. Impact of bowel preparation on efficiency and cost of colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(7):1696–700.

Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P. Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58(1):76–9.

Hughes LD, Done J, Young A. Not 2 old 2 TXT: there is potential to use email and SMS text message healthcare reminders for rheumatology patients up to 65 years old. Health Informatics J. 2011;17(4):266–76.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health//National Cancer Institute grants 5R25TCA081137 and 5R01CA120658.

Conflict of Interest

Jamilia Sly, Sarah Miller, and Lina Jandorf declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sly, J.R., Miller, S.J. & Jandorf, L. The Digital Divide and Health Disparities: a Pilot Study Examining the Use of Short Message Service (SMS) for Colonoscopy Reminders. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 1, 231–237 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-014-0029-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-014-0029-z