Abstract

The prevalence of obesity and overweight is socially patterned, with higher prevalence among women, racial/ethnic minorities, and those with lower socioeconomic status. Contextual factors also affect obesity risk. However, an omitted factor has been incarceration, particularly since it disproportionately affects minorities. This study examines the effects of incarceration on adult male body mass index (BMI) in the USA over the life course, and whether effects vary by race/ethnicity and education. BMI trajectories were analyzed over age using growth curve models of men ages 18–49 from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth panel study. BMI was based on self-reported height/weight (kg/m2). Being currently incarcerated increased BMI, but the effect varied by race/ethnicity and education: Blacks experienced the largest increases, while effects were lowered for men with more education than a high school diploma. Cumulative exposure to prison increased BMI for all groups. These results suggest a differential effect of incarceration on adult male BMI among some racial/ethnic–education minority groups. Particularly, given that these groups are most commonly imprisoned, incarceration may help structure obesity disparities and disadvantage across the life course.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obesity is both a public health priority and a complex, multilevel issue. In 2009–2010, roughly 35 % of US adults were obese [1]. Behavioral, social, and environmental factors have all been shown to have strong effects on obesity risk [2]. Obesity disparities vary by gender and are confounded by racial/ethnic group, socioeconomic status (SES), birth cohort, period effects, age, and other factors [1]. Increased weight gain and the social patterning of obesity are public health concerns, with increased health risks for diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and other conditions [3].

Incarceration may be an important influence on weight gain and has differential effects by race/ethnicity and education. The incarcerated population has grown dramatically, with a recent report finding that 1 of 100 American adults are now in prison [4]. All told, there are presently over 16 million felons and ex-felons, roughly 7.5 % of the US population [5]. Incarceration affects race/ethnic and education groups differently, being a frequent and major life event particularly for young black men [6]. It is estimated that one third of black men have a serious criminal record [7]. Incarceration is also more common among those in poverty and with lower education [6, 8].

This study examines the effects of incarceration on body mass index (BMI) during imprisonment and over the life course in the USA, and whether these effects vary by race/ethnicity and education. While few studies have examined how incarceration affects health [7], they have suggested several causal mechanisms linking the two processes. Schnittker [9] reported that while prisoners may experience some health benefits while incarcerated, these do not persist after release—those with a history of incarceration consistently report worse health. A limitation of that study, however, was the use of an outcome that was nonspecific and could refer to a variety of medical conditions. Massoglia [10] found that history of incarceration is associated with an increased likelihood of stress-related and infectious disease but not with other conditions. Finally, another study showed that incarceration decreases later health functioning and that unequal rates of incarceration may influence observed racial disparities [11]. However, because they measured health outcomes at one point in time (when the respondents reached 40 years of age), these latter two studies were unable to determine the effects of current imprisonment on health status.

Focusing on a single, continuous indicator of health (BMI), this study clearly links incarceration to weight gain. The study uses time-varying indicators of BMI and current and former incarceration to clarify mechanisms affecting weight gain both during imprisonment and upon release. This study also borrows from earlier work relating health to stress and incarceration [10], which have been linked with behaviors associated with weight gain [12]. Massoglia [10] described imprisonment as a primary stressor, involving major behavioral changes in a short period of time. Prison conditions likely directly affect prisoners' weight, both through diet and physical activity and by imposing a major stress. After release, secondary stressors from incarceration affect several social and economic factors linked with incarceration and weight gain.

Stressful conditions and the structuring of daily living may allow incarceration to affect an inmate's weight gain. Prisons control both inmates' diet and their physical activity and influence stress levels. Food quality within prisons and jails is difficult to assess systematically. At the federal level, prepared meals adhere to the Institute of Medicine's recommended dietary intakes [13]. Daily energy allowances for state facilities are determined by state legislatures and vary across states [13]. For jails, diets are governed by local regulations, although most inmates are incarcerated for only a few days [14]. Facilities often have commissary snack bars where inmates may purchase snacks. Regular meals, along with mealtime as an event during the day, may also encourage inmates to eat more often and in greater amounts than they did before imprisonment. Prisons also structure an inmate's daily schedule and the availability of time for physical activity. It is largely unknown whether prisoners engage in enough physical activity [15]. Federal statutes limit the presence of weight lifting and related equipment.

The stressful conditions of prison that relate to other health outcomes are also related to eating behaviors. Psychological distress and depression during imprisonment may increase obesity risk by either increased consumption of energy-dense foods or decreased physical activity [10, 16, 17]. Available evidence suggests that eating behaviors change in response to different types of stressful events, with the clearest link between overeating and increased consumption of food high in fat and sugar due to chronic stress [12]. Recent evidence also indicates that current or recent incarceration is associated with depression and mood disorders [18, 19]. Examining longitudinal studies, Luppino and colleagues found a reciprocal link between depression and obesity: Obesity increases the risk of onset of depression, and depression increases the odds of obesity [20].

Incarceration may also have long-term effects on weight gain. Individuals who do not reenter the penal system face a range of obstacles affected by incarceration, from unemployment and poverty to social isolation and stigma [11]. These factors lead to increased morbidity and mortality among released prisoners [9, 21, 22]. Incarceration decreases social support and hampers social reintegration. Marriages fail, and employment opportunities become hard to find for those with a criminal record. Stigma from a prison record can have social and psychological risks, as well as synergistic effects with cumulative disadvantage and secondary stressors. Lower social status, both absolute and relative, has been linked with greater risk of health problems [21].

Upon release, ex-inmates face a variety of stressful environmental constraints that may interactively increase weight gain. Minority inmates with low SES are released predominately into urban poverty areas [23]. These neighborhoods also have higher crime rates that increase chronic stress exposure [24], fewer options for recreational activities [25], greater numbers of fast-food restaurants full of energy-dense, low-nutrient food, and lower numbers of full-service supermarkets with healthier food options [26]. While research has found that minority inmates do not live in worse neighborhoods after prison [27], whites do, and disadvantaged neighborhoods and stress may have interactive effects. Released inmates with low incomes and undue stress may prefer energy-dense, high calorie food that are more affordable and increase their risk for obesity [28]. Finally, chronic life stress has been linked to weight gain, especially among men [12]. Other evidence indicates that stress-related eating is more common among single or divorced and among unemployed men, all statuses that are commoner among those who have been incarcerated [29].

Finally, roughly one half of released inmates are returned to prison within 3 years [30]. These individuals reenter the penal system with a constellation of risk factors, including preexisting chronic health conditions, mental illness, and substance abuse problems [31, 32]. Cumulative exposure to prison may compound disadvantages as the effects of current and after release spells aggregate. Synergistic interactions may occur between two or more coexistent diseases and social conditions to create an excess burden of disease and social and behavioral risk factors. It is important to understand the forces that tie resulting afflictions together.

While among men population-level obesity rates are lower than those in the general population [33], it is unknown whether and how incarceration affects inmates' weights both during imprisonment and after release. This study builds upon previous work on the effects of incarceration on health [9–11] by using a life course approach. The primary aim is to identify more precisely the mechanisms through which incarceration leads to health problems by focusing on a health behavior of critical importance. This study aims to examine how incarceration affects adult male BMI in the USA by both current incarceration status as well as cumulative exposure to prison, and whether these affects vary by race/ethnic and education groups. Given that incarceration rates disproportionately affect racial minorities and the poor and that there may be differential consequences of incarceration on these groups [11], examining the varying impact of incarceration on the most disadvantaged groups may help clarify the social patterning of obesity risk among men in the USA.

Methods

This study used US nationally representative data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY). Data collection began in 1979 when respondents were between ages 14 and 22. The survey was administered annually through 1994 and biannually afterwards. Retention rates were just under 80 % in 2002. This study used data from male adults ages 18–49 from 1981 to 2006. The analysis was limited to men because the sample of incarcerated women was too small [27]; importantly, there are differences between men and women in the effects of SES, race/ethnicity, and other factors on BMI [34].

The outcome of interest was body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), based on self-reported height and weight. Since weight was not measured during every assessment, only those time intervals when it was measured were included. The independent variable of interest was incarceration. As in some previous research [10, 11], incarceration was assessed through a place of residence indicator (indicating where the respondent was interviewed, including jail or prison); thus, incarceration spells less than 1 or 2 years may be missed since the survey was administered yearly or biannually. Additionally, the indicator does not include information on whether the respondent was incarcerated between interviews—making it impossible to determine the precise duration of an incarceration spell [9]. Incarceration was operationalized in multiple ways to consider the most meaningful assessment of its effect on BMI, including indicators of (1) whether the respondent was currently incarcerated; (2) whether the respondent had never been incarcerated, was currently incarcerated, or had been released; (3) whether the respondent had ever been incarcerated; (4) cumulative exposure as a rolling sum of the number of times the respondent had been previously incarcerated; and (5) the number of years of the current incarceration spell (assuming a contiguous spell if the respondent was incarcerated during the previous interview). All of the incarceration variables were time varying.

Growth curve models were used to examine BMI trajectories over adulthood. Growth curve models account for clustering of observations within persons and can accommodate an inconsistent number of observations per person. Age was used as the time indicator, centered at age 18. A two-level linear model was used, with observations nested within respondents over time. Other covariates included education (time varying and coded as less than high school, high school, and more than high school), race/ethnicity (time constant and coded as non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic, nonblack), and period effects by including year as a time-varying variable to examine period shifts in BMI across all ages. Age, education, and race/ethnicity, as well as period effects, were included because they have documented effects on BMI and incarceration status. Other covariates such as alcohol consumption, cigarette use, and physical activity were either not collected until recently or only collected intermittently and are therefore excluded because they would greatly reduce sample size and the time span of the data. For the incarceration variables, the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) was used to adjudicate between different measures of incarceration [35]; subsequent models tested the addition of other incarceration variables. Interactions were tested between race/ethnicity, education, age, and incarceration variables. Regressions were unweighted, following NLSY guidelines [36]. All models were estimated using Stata 12.1.

To test the robustness of the results, two additional models were fit based on the final model. The first included additional time-varying covariates that have been shown to affect body weight and are likely to be affected by incarceration history: employment (currently employed or not), poverty (in poverty or not), marital status (currently married or not), and whether the respondent resided in an urban area (resided in an urban area or not). The second restricted age to those ages 25 and over, when most formal education is completed, to address potential reverse causality bias due to effects of body weight and incarceration on education.

Results

Descriptive characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. In 1981, the study sample had an average BMI in the normal weight range (BMI 18.5–24.9). By the last observation in 2006, mean BMI had increased almost 6 BMI units to BMI 25–29.9; that is, on average, the respondents were overweight.

Model A in Table 2 presents the results for the unconditional growth model. The intercept, 20.9, represents the average BMI value at age 18. BMI increases steadily and then begins to flatten at older ages. Model B in Table 2 incorporates the period effect. BMI scores have increased linearly, with an average rate of change of 0.10 BMI units. Alternative models including year as a fixed effect showed similar results (not shown).

Models C and D in Table 2 add the effects of race/ethnicity and education. Hispanics and blacks show a greater rate of increase through adulthood than non-Hispanic, nonblack men. Those with more than a high school diploma have a lower BMI than those with less than a high school diploma.

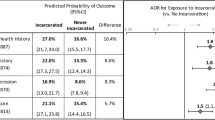

Model E in Table 2 adds the effect of being currently incarcerated. Incarceration increases BMI, particularly for black men. The increase is similar across most education groups, except for a decrease in the effect of incarceration on BMI for men with more than a high school diploma.

Model F in Table 2 adds the effect of the total number of previous incarceration spells. Each previous incarceration spell increases BMI for all race/ethnicity and education groups. As an example, Fig. 1 shows the predicted BMI trajectories over age for men by race/ethnicity and their current incarceration and education status, for those with no previous incarcerations (i.e., comparing between those currently incarcerated and those who are not among those with a score of zero in total number of previous incarceration spells). Each increase in the number of incarcerations would additively increase BMI for all race/ethnicity and education groups.

Model G in Table 3 adds additional covariates of employment, marital, and poverty status and whether the respondent resided in an urban area (model F is repeated for comparison). Being married reduces BMI. The effects of being currently incarcerated remain similar to those in model F, except that those with a high school education also have a reduced effect of incarceration. The number of previous incarcerations also shows similar effects to those in model F, except for men with 3+ previous spells (likely because of reduced sample size).

Model H in Table 3 restricts the estimation sample to those ages 25 and older. The effects of being currently incarcerated remain similar to those in model F, with more robust findings of a reduced effect for those with a high school diploma or higher education. The effect of the number of previous incarcerations is also similar to that in model F.

Discussion

These results suggest that incarceration affects adult male BMI trajectories, both during incarceration and with cumulative exposure, and that these effects vary for some race/ethnicity and education groups: Blacks and those with lower education experienced the largest increases in BMI. Particularly, given that these groups are most commonly imprisoned, incarceration may help structure obesity disparities and disadvantage across the life course. Compared with the general population, both current and prior exposure to prison increase BMI among adult men.

Another study examining the effects of current imprisonment found some initial health improvements that dissipated by release [9]. Correctional facilities control both diet and physical activities, and therefore, it seems reasonable that exposure to these environments would influence BMI. Others have also found that previous history of incarceration is associated with poor health outcomes [9, 11]. However, much previous research has shown similar effects across social groups. This study showed that current incarceration exhibited the strongest effects on blacks and on those with the lowest education, but the effects of cumulative exposure to prison did not differ by race/ethnicity or education. It may be that norms and behaviors during incarceration vary across these groups, but that after release common risks apply similarly to all groups. The effects of cumulative exposure to prison were also robust to controls such as marital status and poverty that are associated with both imprisonment and obesity risk—suggesting a direct effect of previous imprisonment on weight gain.

A limitation of this study is the lack of contextual information about the incarceration spell that could expose the mechanisms behind differential effects on BMI [7]. Being imprisoned could alter behavioral and environmental routines in ways that are compounded through repeat exposures. For instance, lack of adequate time for physical activity could explain BMI increases. Conversely, incarcerated individuals could be increasing lean muscle mass, which would also show up as increased BMI [37]. Racial norms could also influence prisoners' diet and physical activity behaviors. Another study limitation is that BMI was based on self-reported height and weight, so that BMI is likely underestimated, particularly for respondents with higher BMI [38]. However, it is also unknown whether exposure to different norms during incarceration may affect a respondent's self-reported height and weight.

Finally, the negative impact of incarceration on adult BMI among the socially disadvantaged is also compounded by an increase in the percentage of older prisoners. Age is a risk factor for obesity and other chronic medical conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, which also increased among obese individuals [39]. It is estimated that the number of older prisoners increased by 79 % between 2000 and 2009 [40]. This increase, coupled with rising BMI and other health-related costs and conditions, requires a research and policy agenda to identify interventions and long-term solutions to the aging of the incarcerated population.

Conclusion

An array of factors, from individual behaviors to structural and environmental factors, influences the risk of obesity [2]. The present study showed that being incarcerated along with cumulative incarceration spells affected BMI among adult men. Further, the impact of incarceration was strongest for blacks and those with the lowest education. Future research is needed to explore the mechanisms in prisons that influence weight gain and other health behaviors and outcomes. In addition, since the incarcerated population is at high risk of chronic health conditions, mental illness, and substance abuse problems [31], additional research is needed to understand how incarceration interacts with comorbid conditions that may compound social and health disparities, particularly among the most disadvantaged groups.

References

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among us adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:491–7. doi:10.1001/Jama.2012.39.

Huang TT, Drewnosksi A, Kumanyika S, Glass TA. A systems-oriented multilevel framework for addressing obesity in the 21st century. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6:A82.

Ogden CL, Yanovski SZ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2087–102. doi:10.1053/J.Gastro.2007.03.052.

Pew Center on the States. One in 31: the long reach of American corrections. Washington, DC 2009.

Uggen C. Citizenship, democracy, and the civic reintegration of criminal offenders. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci. 2006;605:281–310. doi:10.1177/0002716206286898.

Pettit B, Western B. Mass imprisonment and the life course: race and class inequality in U.S. incarceration. Am Sociol Rev. 2004;69:151–69.

Wakefield S, Uggen C. Incarceration and stratification. Ann Rev Sociol. 2010;36:387–406. doi:10.1146/Annurev.Soc.012809.102551.

Wheelock D, Uggen C. Race, poverty and punishment: the impact of criminal sanctions on racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic inequality. In: Harris D, Lin AC, editors. The colors of poverty: why racial and ethnic disparities persist. Ann Arbor: National Poverty Center, Gerald R. Ford School Of Public Policy, University Of Michigan; 2006.

Schnittker J, John A. Enduring stigma: the long-term effects of incarceration on health. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48:115–30.

Massoglia M. Incarceration as exposure: the prison, infectious disease, and other stress-related illnesses. J Health Soc Behav. 2008;49:56–71.

Massoglia M. Incarceration, health, and racial disparities in health. Law Soc Rev. 2008;42:275–306. doi:10.1111/J.1540-5893.2008.00342.X.

Torres SJ, Nowson CA. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition. 2007;23:887–94. doi:10.1016/J.Nut.2007.08.008.

Spark A. Nutrition in public health: principles, policies, and practice. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2007.

Macready N. Cruel and unusual. Lancet. 2009;373:708–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60421-9.

Herbert K, Plugge E, Foster C, Doll H. Prevalence of risk factors for Non-communicable diseases in prison populations worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet. 2012;379:1975–82. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60319-5.

Hassine V. Life without parole: living in prison today. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Roxbury Publishing Company; 1999.

Lorant V, Deliege D, Eaton W, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:98–112.

Turney K, Wildeman C, Schnittker J. As fathers and felons: explaining the effects of current and recent incarceration on major depression. J Health Soc Behav. 2012;53:465–81. doi:10.1177/0022146512462400.

Schnittker J, Massoglia M, Uggen C. Out and down: incarceration and psychiatric disorders. J Health Soc Behav. 2012;53:448–64. doi:10.1177/0022146512453928.

Luppino FS, De Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2010;67:220–9.

Marmot M. Inequalities in health. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:134–6. doi:10.1016/J.Micpath.2010.05.014.

Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, Cheadle A, Elmore JG, et al. Release from prison-a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:157–65. doi:10.1056/Nejmsa064115.

Massey DS. Categorically unequal: the American stratification system. New York: Russell Sage; 2007.

Cohen S, Doyle W, Baum A. Socioeconomic status is associated with stress hormones. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:414–20.

Yen I, Kaplan G. Poverty area residence and changes in physical activity level: evidence from the alameda county study. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1709–12.

Kawachi I, Berkman L. Neighborhoods and health. New York: Oxford University; 2003.

Massoglia M, Firebaugh G, Warner C. Racial variation in the effect of incarceration on neighborhood attainment. Am Sociol Rev. 2012;78:142–65. doi:10.1177/0003122412471669.

Drewnowski A, Barratt-Fornell A. Do healthier diets cost more? Nutr Today. 2004;39:161–8. doi:10.1097/00017285-200407000-00006.

Laitinen J, Ek E, Sovio U. Stress-related eating and drinking behavior and body mass index and predictors of this behavior. Prev Med. 2002;34(1):29–39.

Kamala M-K, Visher CA. Health and prisoner reentry: how physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions shape the process of reintegration: urban Institute; 2008.

Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd JW, Lasser KE, Mccormick D, Bor DH, et al. The health and health care of Us prisoners: results of a nationwide survey. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:666–72. doi:10.2105/Ajph.2008.144279.

Baillargeon J, Binswanger IA, Penn JV, Williams BA, Murray OJ. Psychiatric disorders and repeat incarcerations: the revolving prison door. Am J Psychiatr. 2009;166:103–9. doi:10.1176/Appi.Ajp.2008.08030416.

Houle B. Obesity disparities among disadvantaged men: national adult male inmate prevalence pooled with non-incarcerated estimates, United States, 2002–2004. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(10):1667–73.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Mcdowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–55.

Raftery AE. Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociol Methodol. 1995;25:111–63.

NIs user services. Sample weights & design effects. In: Nlsy97 User’s Guide. Accessed 3/6/2013.

Oreopoulos A, Ezekowitz JA, Mcalister FA, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Fonarow GC, Norris CM, et al. Association between direct measures of body compposition and prognostic factors in chronic heart failure. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:609–17. doi:10.4065/Mcp.20.

Gorber SC, Tremblay M, Moher D, Gorber B. A comparison of direct vs. self-report measures for assessing height, weight and body mass index: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2007;8:307–26. doi:10.1111/J.1467-789x.2007.00347.X.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: National Institutes Of Health1998 Contract No.: 98-4083.

Williams BA, Stern MF, Mellow J, Safer M, Greifinger RB. Aging in correctional custody: setting a policy agenda for older prisoner health care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1475–81.

Acknowledgments

Partial support for this research came from a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development research infrastructure grant, 5R24 HD066613-03, to the University of Colorado Population Center in the Institute of Behavioral Science at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Houle, B. The Effect of Incarceration on Adult Male BMI Trajectories, USA, 1981–2006. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 1, 21–28 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-013-0003-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-013-0003-1