Abstract

Purpose of Review

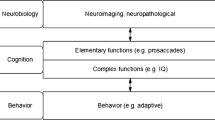

Environmental toxicants and psychosocial stressors share many biological substrates and influence overlapping physiological pathways. Increasing evidence indicates stress-induced changes to the maternal milieu may prime rapidly developing physiological systems for disruption by concurrent or subsequent exposure to environmental chemicals. In this review, we highlight putative mechanisms underlying sex-specific susceptibility of the developing neuroendocrine system to the joint effects of stress or stress correlates and environmental toxicants (bisphenol A, alcohol, phthalates, lead, chlorpyrifos, and traffic-related air pollution).

Recent Findings

We provide evidence indicating that concurrent or tandem exposure to chemical and non-chemical stressors during windows of rapid development is associated with sex-specific synergistic, potentiated and reversed effects on several neuroendocrine endpoints related to hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function, sex steroid levels, neurotransmitter circuits, and innate immune function. We additionally identify gaps, such as the role that the endocrine-active placenta plays, in our understanding of these complex interactions. Finally, we discuss future research needs, including the investigation of non-hormonal biomarkers of stress.

Summary

We demonstrate multiple physiologic systems are impacted by joint exposure to chemical and non-chemical stressors differentially among males and females. Collectively, the results highlight the importance of evaluating sex-specific endpoints when investigating the neuroendocrine system and underscore the need to examine exposure to chemical toxicants within the context of the social environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Culbert-Koehn J. Don’t get stuck in the mother: regression in analysis. J Anal Psychol. 1997;42:99–104.

Freud S. Inhibitions, symptoms and anxiety. London: Hogarth Press; 1926.

Mitrani JL. Toward an understanding of unmentalized experience. Psychoanal Q. 1995;64(1):68–112.

Beydoun H, Saftlas AF. Physical and mental health outcomes of prenatal maternal stress in human and animal studies: a review of recent evidence. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008;22(5):438–66.

Savitz D, Dunkel-Schetter C. Preterm birth: causes, consequences and prevention. In: Behrman R, Butler AS, editors. Behavioral and psychosocial contributors to preterm birth. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2006. p. 87–123.

Rappaport SM. Implications of the exposome for exposure science. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2011;21(1):5–9.

Weiss B, Bellinger DC. Social ecology of children's vulnerability to environmental pollutants. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(10):1479–85.

Wright RJ. Moving towards making social toxins mainstream in children’s environmental health. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(2):222–9.

Pfaff DW, Christen Y. Multiple origins of sex differences in brain neuroendocrine functions and their pathologies. Research and perspectives in endocrine interactions. Heidelberg: Springer; 2013.

• Antonelli MC, Pallares ME, Ceccatelli S, Spulber S. Long-term consequences of prenatal stress and neurotoxicants exposure on neurodevelopment. Prog Neurobiol. 201; 156:21–35. The authors provide a detailed summary of neurodevelopmental consequences of exposure to gestational stress and environmental toxicants, including sex-specific effects, and the overlapping pathways they each target.

Graignic-Philippe R, Dayan J, Chokron S, Jacquet AY, Tordjman S. Effects of prenatal stress on fetal and child development: a critical literature review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;43:137–62.

Jurewicz J, Polanska K, Hanke W. Exposure to widespread environmental toxicants and children's cognitive development and behavioral problems. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2013;26(2):185–204.

Cohen S, Kessler R, Underwood GL. Measuring stress: a guide for health and social scientists. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995.

Contrada R, Baum A. The handbook of stress science: Biology, Psychology, and Health. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2010.

Mustieles V, Perez-Lobato R, Olea N, Fernandez MF, Bisphenol A. Human exposure and neurobehavior. Neurotoxicology. 2015;49:174–84.

Prasanth GK, Divya LM, Sadasivan C. Bisphenol-A can bind to human glucocorticoid receptor as an agonist: an in silico study. J Appl Toxicol. 2010;30(8):769–74.

Aluru N, Leatherland JF, Vijayan MM. Bisphenol A in oocytes leads to growth suppression and altered stress performance in juvenile rainbow trout. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10741.

Giesbrecht GF, Liu J, Ejaredar M, Dewey D, Letourneau N, Campbell T, et al. Urinary bisphenol A is associated with dysregulation of HPA-axis function in pregnant women: findings from the APrON cohort study. Environ Res. 2016;151:689–97.

Moisiadis VG, Matthews SG. Glucocorticoids and fetal programming part 2: mechanisms. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(7):403–11.

Tegethoff M, Pryce C, Meinlschmidt G. Effects of intrauterine exposure to synthetic glucocorticoids on fetal, newborn, and infant hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in humans: a systematic review. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(7):753–89.

Panagiotidou E, Zerva S, Mitsiou DJ, Alexis MN, Kitraki E. Perinatal exposure to low-dose bisphenol A affects the neuroendocrine stress response in rats. J Endocrinol. 2014;220(3):207–18.

Ward IL, Ward OB, Affuso JD, Long WD 3rd, French JA, Hendricks SE. Fetal testosterone surge: specific modulations induced in male rats by maternal stress and/or alcohol consumption. Horm Behav. 2003;43(5):531–9.

Ward OB, Ward IL, Denning JH, Hendricks SE, French JA. Hormonal mechanisms underlying aberrant sexual differentiation in male rats prenatally exposed to alcohol, stress, or both. Arch Sex Behav. 2002;31(1):9–16.

Drake AJ, van den Driesche S, Scott HM, Hutchison GR, Seckl JR, Sharpe RM. Glucocorticoids amplify dibutyl phthalate-induced disruption of testosterone production and male reproductive development. Endocrinology. 2009;150(11):5055–64.

Virgolini MB, Rossi-George A, Lisek R, Weston DD, Thiruchelvam M, Cory-Slechta DA. CNS effects of developmental Pb exposure are enhanced by combined maternal and offspring stress. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29(5):812–27.

Cory-Slechta DA, Virgolini MB, Thiruchelvam M, Weston DD, Bauter MR. Maternal stress modulates the effects of developmental lead exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(6):717–30.

Cory-Slechta DA, Stern S, Weston D, Allen JL, Liu S. Enhanced learning deficits in female rats following lifetime pb exposure combined with prenatal stress. Toxicol Sci. 2010;117(2):427–38.

Weston HI, Weston DD, Allen JL, Cory-Slechta DA. Sex-dependent impacts of low-level lead exposure and prenatal stress on impulsive choice behavior and associated biochemical and neurochemical manifestations. Neurotoxicology. 2014;44:169–83.

Slotkin TA, Card J, Seidler FJ. Prenatal dexamethasone, as used in preterm labor, worsens the impact of postnatal chlorpyrifos exposure on serotonergic pathways. Brain Res Bull. 2014;100:44–54.

Slotkin TA, Card J, Infante A, Seidler FJ. Prenatal dexamethasone augments the sex-selective developmental neurotoxicity of chlorpyrifos: implications for vulnerability after pharmacotherapy for preterm labor. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2013;37:1–12.

Levin ED, Cauley M, Johnson JE, Cooper EM, Stapleton HM, Ferguson PL, et al. Prenatal dexamethasone augments the neurobehavioral teratology of chlorpyrifos: significance for maternal stress and preterm labor. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2014;41:35–42.

Bolton JL, Huff NC, Smith SH, Mason SN, Foster WM, Auten RL, et al. Maternal stress and effects of prenatal air pollution on offspring mental health outcomes in mice. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121(9):1075–82.

Chen F, Zhou L, Bai Y, Zhou R, Chen L. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hyperactivity accounts for anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in rats perinatally exposed to bisphenol A. J Biomed Res. 2015;29(3):250–8.

Steingard R, Biederman J, Keenan K, Moore C. Comorbidity in the interpretation of dexamethasone suppression test results in children: a review and report. Biol Psychiatry. 1990;28(3):193–202.

Corbier P, Roffi J, Rhoda J. Female sexual behavior in male rats: effect of hour of castration at birth. Physiol Behav. 1983;30(4):613–6.

Hoepfner BA, Ward IL. Prenatal and neonatal androgen exposure interact to affect sexual differentiation in female rats. Behav Neurosci. 1988;102(1):61–5.

Shansky RM. Sex differences in the central nervous system. Neuroscience Net Reference Book Series Book 4. Boston: Elsevier Academic Press; 2016.

Hampl R, Kubatova J, Starka L. Steroids and endocrine disruptors—history, recent state of art and open questions. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;155(Pt B):217–23.

Ward IL, Bennett AL, Ward OB, Hendricks SE, French JA. Androgen threshold to activate copulation differs in male rats prenatally exposed to alcohol, stress, or both factors. Horm Behav. 1999;36(2):129–40.

Supornsilchai V, Soder O, Svechnikov K. Stimulation of the pituitary-adrenal axis and of adrenocortical steroidogenesis ex vivo by administration of di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate to prepubertal male rats. J Endocrinol. 2007;192(1):33–9.

Sekaran S, Jagadeesan A. In utero exposure to phthalate downregulates critical genes in Leydig cells of F1 male progeny. J Cell Biochem. 2015;116(7):1466–77.

Akingbemi BT, Youker RT, Sottas CM, Ge R, Katz E, Klinefelter GR, et al. Modulation of rat Leydig cell steroidogenic function by di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate. Biol Reprod. 2001;65(4):1252–9.

Araki A, Mitsui T, Goudarzi H, Nakajima T, Miyashita C, Itoh S, et al. Prenatal di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate exposure and disruption of adrenal androgens and glucocorticoids levels in cord blood: the Hokkaido Study. Sci Total Environ. 2017;581-582:297–304.

Ferguson KK, Peterson KE, Lee JM, Mercado-Garcia A, Blank-Goldenberg C, Tellez-Rojo MM, et al. Prenatal and peripubertal phthalates and bisphenol A in relation to sex hormones and puberty in boys. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;47:70–6.

Watkins DJ, Tellez-Rojo MM, Ferguson KK, Lee JM, Solano-Gonzalez M, Blank-Goldenberg C, et al. In utero and peripubertal exposure to phthalates and BPA in relation to female sexual maturation. Environ Res. 2014;134:233–41.

Swan SH, Sathyanarayana S, Barrett ES, Janssen S, Liu F, Nguyen RH, et al. First trimester phthalate exposure and anogenital distance in newborns. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(4):963–72.

Thankamony A, Pasterski V, Ong KK, Acerini CL, Hughes IA. Anogenital distance as a marker of androgen exposure in humans. Andrology. 2016;4(4):616–25.

Pasterski V, Acerini CL, Dunger DB, Ong KK, Hughes IA, Thankamony A, et al. Postnatal penile growth concurrent with mini-puberty predicts later sex-typed play behavior: evidence for neurobehavioral effects of the postnatal androgen surge in typically developing boys. Horm Behav. 2015;69:98–105.

Schettler T. Human exposure to phthalates via consumer products. Int J Androl. 2006;29(1):134–9.

Zarean M, Keikha M, Poursafa P, Khalighinejad P, Amin M, Kelishadi R. A systematic review on the adverse health effects of di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23(24):24642–93.

Barrett ES, Parlett LE, Sathyanarayana S, Redmon JB, Nguyen RH, Swan SH. Prenatal stress as a modifier of associations between phthalate exposure and reproductive development: results from a multicentre pregnancy cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2016;30(2):105–14.

Barrett ES, Parlett LE, Sathyanarayana S, Liu F, Redmon JB, Wang C, et al. Prenatal exposure to stressful life events is associated with masculinized anogenital distance (AGD) in female infants. Physiol Behav. 2013;114-115:14–20.

Sullivan RM, Dufresne MM. Mesocortical dopamine and HPA axis regulation: role of laterality and early environment. Brain Res. 2006;1076(1):49–59.

Strominger N, Demarest R, Laemle L. Noback’s human nervous system. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2012.

Rossi-George A, Virgolini MB, Weston D, Thiruchelvam M, Cory-Slechta DA. Interactions of lifetime lead exposure and stress: behavioral, neurochemical and HPA axis effects. Neurotoxicology. 2011;32(1):83–99.

Hensler JG, Artigas F, Bortolozzi A, Daws LC, De Deurwaerdere P, Milan L, et al. Catecholamine/serotonin interactions: systems thinking for brain function and disease. Adv Pharmacol. 2013;68:167–97.

Kapoor A, Dunn E, Kostaki A, Andrews MH, Matthews SG. Fetal programming of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal function: prenatal stress and glucocorticoids. J Physiol. 2006;572(Pt 1):31–44.

Baarendse PJ, Vanderschuren LJ. Dissociable effects of monoamine reuptake inhibitors on distinct forms of impulsive behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2012;219(2):313–26.

Walderhaug E, Magnusson A, Neumeister A, Lappalainen J, Lunde H, Refsum H, et al. Interactive effects of sex and 5-HTTLPR on mood and impulsivity during tryptophan depletion in healthy people. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(6):593–9.

Chlorpyrifos. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Available: https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/chlorpyrifos.

Prueitt RL, Goodman JE, Bailey LA, Rhomberg LR. Hypothesis-based weight-of-evidence evaluation of the neurodevelopmental effects of chlorpyrifos. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2011;41(10):822–903.

Slotkin TA, Seidler FJ. The alterations in CNS serotonergic mechanisms caused by neonatal chlorpyrifos exposure are permanent. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2005;158(1–2):115–9.

Aldridge JE, Seidler FJ, Meyer A, Thillai I, Slotkin TA. Serotonergic systems targeted by developmental exposure to chlorpyrifos: effects during different critical periods. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111(14):1736–43.

Rauh VA, Garcia WE, Whyatt RM, Horton MK, Barr DB, Louis ED. Prenatal exposure to the organophosphate pesticide chlorpyrifos and childhood tremor. Neurotoxicology. 2015;51:80–6.

Rauh VA, Garfinkel R, Perera FP, Andrews HF, Hoepner L, Barr DB, et al. Impact of prenatal chlorpyrifos exposure on neurodevelopment in the first 3 years of life among inner-city children. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):e1845–59.

Bouchard MF, Chevrier J, Harley KG, Kogut K, Vedar M, Calderon N, et al. Prenatal exposure to organophosphate pesticides and IQ in 7-year-old children. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(8):1189–95.

Emgard M, Paradisi M, Pirondi S, Fernandez M, Giardino L, Calza L. Prenatal glucocorticoid exposure affects learning and vulnerability of cholinergic neurons. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28(1):112–21.

St-Pierre J, Laurent L, King S, Vaillancourt C. Effects of prenatal maternal stress on serotonin and fetal development. Placenta. 2016;48(Suppl 1):S66–71.

Coussons-Read ME, Okun ML, Nettles CD. Psychosocial stress increases inflammatory markers and alters cytokine production across pregnancy. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(3):343–50.

Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Unraveling the longstanding scars of early neurodevelopmental stress. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(11):788–9.

Johnson, FK, Kaffman A. Early life stress perturbs the function of microglia in the developing rodent brain: new insights and future directions. Brain Behav Immun. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2017.06.008.

McCarthy M, Nugent BM, Lenz KM. Neuroimmunology and neuroepigenetics in the establishment of sex differences in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18:471–84.

VanRyzin JW, Yu SJ, Perez-Pouchoulen M, McCarthy MM. Temporary depletion of microglia during the early postnatal period induces lasting sex-dependent and sex-independent effects on behavior in rats. eNeuro. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0297-16.2016

Bilbo SD, Schwarz JM. The immune system and developmental programming of brain and behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2012;33(3):267–86.

• Costa LG, Cole TB, Coburn J, Chang YC, Dao K, Roque PJ. Neurotoxicity of traffic-related air pollution. Neurotoxicology. 2017;59:133–9. This recent review summarizes results from toxicologic and epidemiologic research investigating neurodevelopmental and neurodegeneraive effects of exposure to air pollution. The paper highlights the need for future research investigating sex differences and gene-environment interactions.

Cowell WJ, Bellinger DC, Coull BA, Gennings C, Wright RO, Wright RJ. Associations between prenatal exposure to black carbon and memory domains in urban children: modification by sex and prenatal stress. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142492.

Tyrka AR, Parade SH, Valentine TR, Eslinger NM, Seifer R. Adversity in preschool-aged children: effects on salivary interleukin-1beta. Dev Psychopathol. 2015;27(2):567–76.

De Prins S, Dons E, Van Poppel M, Int Panis L, Van de Mieroop E, Nelen V, et al. Airway oxidative stress and inflammation markers in exhaled breath from children are linked with exposure to black carbon. Environ Int. 2014;73:440–6.

Bale TL. Sex differences in prenatal epigenetic programming of stress pathways. Stress. 2011;14(4):348–56.

Howerton CL, Bale TL. Prenatal programing: at the intersection of maternal stress and immune activation. Horm Behav. 2012;62(3):237–42.

Murphy VE, Smith R, Giles WB, Clifton VL. Endocrine regulation of human fetal growth: the role of the mother, placenta, and fetus. Endocr Rev. 2006;27(2):141–69.

• Howerton CL, Bale TL. Targeted placental deletion of OGT recapitulates the prenatal stress phenotype including hypothalamic mitochondrial dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(26):9639–44. This important paper demonstrates that knocking out a specific placental gene results in mice pups characterized by stress response similar to those of mice exposed to stress during gestation. The paper provides convincing evidence that in mice, levels of this protein (OGT) may serve as a placental biomarker of stress.

Howerton CL, Morgan CP, Fischer DB, Bale TL. O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) as a placental biomarker of maternal stress and reprogramming of CNS gene transcription in development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(13):5169–74.

Smith MN, Griffith WC, Beresford SA, Vredevoogd M, Vigoren EM, Faustman EM. Using a biokinetic model to quantify and optimize cortisol measurements for acute and chronic environmental stress exposure during pregnancy. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2014;24(5):510–6.

Reynolds RM. Glucocorticoid excess and the developmental origins of disease: two decades of testing the hypothesis—2012 Curt Richter Award Winner. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(1):1–11.

Benediktsson R, Calder AA, Edwards CR, Seckl JR. Placental 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase: a key regulator of fetal glucocorticoid exposure. Clin Endocrinol. 1997;46(2):161–6.

Mitchell C, Hobcraft J, McLanahan SS, Siegel SR, Berg A, Brooks-Gunn J, et al. Social disadvantage, genetic sensitivity, and children’s telomere length. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(16):5944–9.

• Shalev I. Early life stress and telomere length: investigating the connection and possible mechanisms: a critical survey of the evidence base, research methodology and basic biology. BioEssays. 2012;34(11):943–52. This thorough review paper summarizes the evidence linking early-life stress with telomere dynamics and also provides a clear and concise review of methodological issues and limitations relating to telomere measurement (i.e., relating to assay choice, cell type, measurement error).

Bonetti D, Martina M, Falcettoni M, Longhese MP. Telomere-end processing: mechanisms and regulation. Chromosoma. 2014;123:57–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00412-013-0440-y

Entringer S, Epel ES, Kumsta R, Lin J, Hellhammer DH, Blackburn EH, et al. Stress exposure in intrauterine life is associated with shorter telomere length in young adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(33):E513–8.

Entringer S, Epel ES, Lin J, Buss C, Shahbaba B, Blackburn EH, et al. Maternal psychosocial stress during pregnancy is associated with newborn leukocyte telomere length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(2):134 e1-7.

Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Gouin JP, Weng NP, Malarkey WB, Beversdorf DQ, Glaser R. Childhood adversity heightens the impact of later-life caregiving stress on telomere length and inflammation. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(1):16–22.

Tyrka AR, Price LH, Kao HT, Porton B, Marsella SA, Carpenter LL. Childhood maltreatment and telomere shortening: preliminary support for an effect of early stress on cellular aging. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):531–4.

Moisiadis VG, Matthews SG. Glucocorticoids and fetal programming part 1: outcomes. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(7):391–402.

Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(1):46–56.

Watanabe M, Fukuda A, Nabekura J. The role of GABA in the regulation of GnRH neurons. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:387.

Ward IL, Ward OB, French JA, Hendricks SE, Mehan D, Winn RJ. Prenatal alcohol and stress interact to attenuate ejaculatory behavior, but not serum testosterone or LH in adult male rats. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110(6):1469–77.

King K, Ogle C. Negative life events vary by neighborhood and mediate the relation between neighborhood context and psychological well-being. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e93539.

Myers HF. Ethnicity- and socio-economic status-related stresses in context: an integrative review and conceptual model. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):9–19.

Wade R Jr, Cronholm PF, Fein JA, Forke CM, Davis MB, Harkins-Schwarz M, et al. Household and community-level adverse childhood experiences and adult health outcomes in a diverse urban population. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;52:135–45.

Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–8.

Wilson WC, Rosenthal BS. The relationship between exposure to community violence and psychological distress among adolescents: a meta-analysis. Violence Vict. 2003;18(3):335–52.

Becerra BJ, Sis-Medina RC, Reyes A, Becerra MB. Association between food insecurity and serious psychological distress among hispanic adults living in poverty. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E206.

Chen E, Miller GE. Socioeconomic status and health: mediating and moderating factors. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:723–49. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185634.

Bradley RH, Corwyn RF, McAdoo HP, Coll CG. The home environments of children in the United States part I: variations by age, ethnicity, and poverty status. Child Dev. 2001;72(6):1844–67.

• Corburn J. Concepts for studying urban environmental justice. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2017;4(1):61–7. This review paper summarizes conceptual thinking and current research frameworks related to environmental justice in the USA with a focus on urban neighborhoods.

Cushing L, Morello-Frosch R, Wander M, Pastor M. The haves, the have-nots, and the health of everyone: the relationship between social inequality and environmental quality. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:193–209.

Vrijheid M, Martinez D, Aguilera I, Ballester F, Basterrechea M, Esplugues A, et al. Socioeconomic status and exposure to multiple environmental pollutants during pregnancy: evidence for environmental inequity? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(2):106–13.

CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Disparities & Inequalities Report—United States. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Suppl. 2013;62:1–187.

White BM, Bonilha HS, Ellis C Jr. Racial/ethnic differences in childhood blood lead levels among children <72 months of age in the United States: a systematic review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;3(1):145–53.

Moody HA, Darden JT, Pigozzi BW. The relationship of neighborhood socioeconomic differences and racial residential segregation to childhood blood lead levels in Metropolitan Detroit. J Urban Health. 2016;93(5):820–39.

McCormick MC, Litt JS, Smith VC, Zupancic JA. Prematurity: an overview and public health implications. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:367–79.

CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey: Summary Health Statistics. 2015. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/shs/tables.htm.

Braveman PA, Egerter SA, Mockenhaupt RE. Broadening the focus: the need to address the social determinants of health. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:S4–18.

Funding

During her training and preparation of this manuscript, WJC was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Science grants T32 ES023772 and T32 ES007322 and Environmental Protection Agency STAR Fellowship: FP-91779001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclaimers

This publication was developed under STAR Fellowship Assistance Agreement no. FP-91779001 awarded by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). It has not been formally reviewed by EPA. The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Synthetic Chemicals and Health

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cowell, W.J., Wright, R.J. Sex-Specific Effects of Combined Exposure to Chemical and Non-chemical Stressors on Neuroendocrine Development: a Review of Recent Findings and Putative Mechanisms. Curr Envir Health Rpt 4, 415–425 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-017-0165-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-017-0165-9