Abstract

Traffic congestion has become a critical issue in developing countries, as it tends to increase social costs in terms of travel cost and time, energy consumption and environmental degradation. With limited resources, reducing travel demand by influencing individuals’ travel behavior can be a better long-term solution. To achieve this objective, alternate travel options need to be provided so that people can commute comfortably and economically. This study aims to identify key motives and constraints in the consideration of carpooling policy with the help of stated preference questionnaire survey that was conducted in Lahore City. The designed questionnaire includes respondents’ socioeconomic demographics, and intentions and stated preferences on carpooling policy. Factor analysis was conducted on travelers’ responses, and a structural model was developed for carpooling. Survey and modeling results reveal that social, environmental and economic benefits, disincentives on car use, preferential parking treatment for carpooling, and comfort and convenience attributes are significant determinants in promoting carpooling. However, people with strong belief in personal privacy, security, freedom in traveling and carpooling service constraints would have less potential to use the carpooling service. In addition, pro-auto and pro-carpooling attitudes, marital status, profession and travel purpose for carpooling are also underlying factors. The findings implicate that to promote carpooling policy it is required to consider appropriate incentives on this service and disincentives on use of private vehicle along with modification of people’s attitudes and intentions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The metropolitan cities are facing the dilemma of traffic congestion due to the rapid increase in urban population and the travel demand. With limited public transportation facilities, people prefer to commute by private vehicles and mobility in the cities has become auto-dependent. The rapid increase in motorized traffic is imposing a serious threat to the communities because of the increase in travel time, travel cost, energy consumption and environmental pollution. In developing regions, capacity of infrastructure usually increases to meet the desired demand, but at the end, it imposes an additional economic burden on the society. An alternative approach to minimize the traffic congestion and its related problems is the consideration and implementation of travel demand management (TDM) policies. The TDM policies are those soft and hard measures that are used to reduce the travel demand of individuals by influencing their travel behavior [1]. Various TDM measures are available for consideration such as public transport improvements, parking treatments, land use control, advance information to travelers, carpooling and imposition of taxes on car ownership and usage. Specific measures can be considered for implementation based on the nature of problems to address in a particular city.

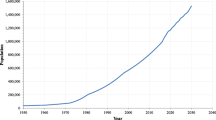

Like other big cities, Lahore City is also facing the problem of acute traffic congestion. Lahore is the second largest city of Pakistan with a population of almost 8.65 million and an area of 1792 km2 [2]. The urban population growth rate is almost 3%, and vehicle ownership is increasing at a rate of 17% per annum [2]. The city is concentrated with employment opportunities, and educational, medical and other allied facilities that generate huge travel demand on the road network. In the absence of an efficient public transport system in the city, the trend for more car ownership and usage is increasing. To tackle traffic congestion and related social and environmental problems in a sustainable manner, we need to consider demand management measures along with supply side measures. In this study, carpooling TDM measures were selected for evaluation in the local socioeconomic context. Carpooling service is helpful in reducing traffic congestion, energy consumption and environmental problems. According to Sheldon and Heywood [3],‘carpooling’ is the concept whereby vehicles are available within a community or locality for individuals to hire on a ‘club’ basis, or a carpool is a system in which several people share rides to work, school or other destinations. This system helps to save money by dividing fuel costs among several individuals, instead of each person bearing the whole cost of fuel [4]. In this study, carpooling refers to a shared transport service that either runs on mutual coordination of the users or is provided by some organizations from certain residential places to certain work/education places. At present, there is a trend of traveling together among people especially students on a same vehicle with mutual understanding having same origins and destinations as it helps them to reduce travel cost. However, well-organized or formal carpooling service does not exist in Lahore City at present, and studies need to be conducted for the design and implementation of an organized carpooling service in Lahore.

Various studies demonstrate different factors that contribute toward success and failure of carpooling. It is very important to evaluate the potential of carpooling in the local context of a particular region. However, most of the existing studies are related to the developed countries and very limited literature is available regarding potential of carpooling in developing countries. Therefore, this paper aims to identify the significant factors that can influence the acceptability and effectiveness of carpooling policy in the local context of Lahore City. The findings of this study are based on the results of a stated preference questionnaire survey, factor analysis and structural equation modeling (SEM). The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the related literature. Section 3 describes the data collection methods. Section 4 presents the discussion on study results. And the last section summarizes the key findings and their implications.

2 Literature review

Seyedabrishami et al. [5] believe that with the help of appropriate strategies, it is possible to increase carpooling among travelers and such an increase will help in reducing annual fuel consumption. In the USA and Canada, ridesharing almost represents 8%–11% of the transportation modal share, and the relationship of ridesharing policies with infrastructure development, traffic congestion, energy consumption and related emissions needs to understand well [6]. Manzini and Pareschi [7] state that carpooling is an effective strategy to reduce transport demand, travel costs and other related externalities. The acceptability of such TDM measures by public and their effectiveness in changing travel behavior are associated issues and need to be evaluated. Many factors may contribute toward such aspects of carpooling policy. These factors mainly include sociodemographics, lifestyles, intentions and attitudes of the individuals. It is believed that travel-related strategies are likely to be influenced by individuals’ lifestyles and attitudes [8,9,10,11,12,13]. In some other studies, different attitudes have been found to influence individuals’ travel behavior and related demand management strategies [14,15,16]. Particular travel incentives and restrictions on use of private vehicle are key determinants in the success of a particular TDM policy [8]. According to Sheldon and Heywood [3], low-cost, convenient and well-maintained services are the key attributes in defining the effective carpooling service. People have more potential of carpooling if it is combined with high occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes [17]. However, Syedabrishami et al. [5] state that HOV lanes that reduce travel time for ridesharing may not have high influence on carpooling tendency of travelers. According to Li et al. [17], enjoying traveling with others, time saving, helping the environment and society are important factors in carpooling, whereas carpooling partner matching programs, employer carpooling incentives and preferred parking at work are generally the least important factors for travelers in consideration of carpooling.

According to Sharma et al. [18], a significant portion of the car drivers and two-wheelers feel tired of driving alone and look for comfortable, faster and cheaper mode of commuting. Correia and Viegas [19] believe that carpooling is a mode of lower-income strata and saving money is an important reason for participating in it. They further state that this should provide a way for persons to trust and interact with other people at least with their colleagues. Ciari [20] states that driving alone, safety, specific travelers group and guaranteed service for back home trips are main reasons for preferring carpooling to private vehicles. Other factors may include incentives on carpooling service such as safety, time and money saving, trip purpose, age, travel frequency, disincentives on use of private vehicle and travelers’ attitudes [8, 14, 21,22,23]. According to the study by Malodia and Singla [24] in Indian cities, extra travel time, walking time to reach the meeting point, waiting time and cost savings are the influencing exploratory variables related to proper utility of carpooling service. Results of the ordered probit model reveal that the distance from carpooling meeting point, parking cost, Web application, matching preference and flexibility of services have significant relationships with people’s propensity for ridesharing or carpooling [25]. Srivastava [26] states many factors that enhance the use of such shared facilities, e.g., incentives, mixed approach, low cost and incentives to drivers. Soltys [27] presents that proximity to car zones, motivation to save time, gender and current use of transit facilities are the significant factors related to use of carpooling service. A detailed study on carpooling in the USA and Vermont [28] provides a list of major obstacles to carpooling, including rates of car ownership, household size, dispersed land settlement patterns, changes in travel behavior and attitudinal variables. This study also states that vehicle occupancy rates increase with the help of carpooling for work trip, and could help in reducing energy used in transportation infrastructure. Delhomme and Gheorghiu [29] believe that carpoolers are more likely to be women and those people who have children, people having positive attitudes toward public transport and those having awareness regarding environment. The related literature provides many factors that contribute toward success and failure of carpooling policy in different parts of the world. However, it is required to identify the scope of such TDM policies in the local socioeconomic context of Lahore City. Findings of local level studies are very important, as each city possesses unique characteristics in terms of transportation infrastructure and its problems, population growth and land use pattern, social and cultural values, and people’s lifestyles. Imposition of carpooling or other transportation policies based on findings for other cities may result in poor public acceptability and failure. Therefore, consideration of local factors in the design of transportation policies is vital for their success.

3 Data collection methods

To accomplish stated objectives, required data were collected with the help of a questionnaire survey and details are given in the next subsections.

3.1 Questionnaire design

A questionnaire consisting of five parts was designed in this study. This questionnaire comprises various aspects of travel behavior in relation to evaluation of potential of carpooling policy. First part of the questionnaire consists of personal and traveling information of the respondents as given in Table 1, i.e., gender, age, marital status, education, monthly income, profession, traveling mode, trip purpose, vehicle ownership, driving a car or not and possessing driving license or not. The second part involves travelers’ responses on stated carpooling scenarios such as willingness to use carpooling if HOV lanes exist, the number of people a person would like to share the ride with, interest in reduced travel cost in carpooling and the best option that describes the purpose of carpooling. ‘Shopping trip’ as the main purpose of carpooling was included with respect to the students, as they like to travel together for shopping. Therefore, it is supposed that they may prefer carpooling to other modes for shopping trips. The detail of each question is shown in the “Appendix” section.

In the third part of the questionnaire, respondents were asked to rate the most important benefits of carpooling if they do carpooling or considering to do. All statements in this part were designed considering the social, environmental and service benefits of carpooling that the travelers are supposed to get if they use it. Part 4 consists of two sections. First section is about people stated preferences to use carpooling service under some incentives on service and disincentives on use of private car. Main service incentives include safe, enjoyable and comfortable service, free parking and preferential treatment for carpooling vehicles at parking facilities. Main disincentives on use of private cars include high travel and parking cost and limited parking at destination. In the second section, respondents were asked to show levels of agreement for their main reasons of preferring private vehicle to carpooling service. The reasons include statements on personal freedom, security and privacy in traveling, and some service attributes of traveling modes. These statements were designed considering the competitiveness of two modes in their service. The last part of the questionnaire comprises several statements on individuals’ lifestyles and attitudes and travel intentions. The main motives behind design of these statements were the priorities in selecting a traveling mode, daily lifestyle pattern in relation to traveling, social attraction and personal status-oriented aspects of traveling, and personal intentions of ride sharing with friends, colleagues and family members for daily traveling. The other main motive in designing these statements was to check the influence of such stated lifestyles and attitudes on individual’s propensity for carpooling service. All questions in parts 3, 4 and 5 were evaluated using five-point Likert scales, i.e., strongly disagree (1), somewhat disagree (2), neither disagree nor agree (3), somewhat agree (4) and strongly agree (5). Questionnaire items in all parts were designed in such a way that proper responses of current car users and potential car users can be obtained in relation to various aspects of carpooling. In this study, potential car users are supposed to be those travelers who belong to middle-income group and currently use motorcycles. These mainly included engineering students and graduates, and professionals belonging to middle- and high-income category. Instructions for respondents to fill in the questionnaire were provided at the beginning of each part. To make questionnaire easy and understandable for the respondents, some pictures or graphics were included related to actual appearance of carpooling service and HOV lanes. Descriptions are also included on how carpooling service works and what are the key benefits of introducing this service in Lahore City.

3.2 Survey in study area

This survey was conducted in Lahore City with the help of final year undergraduate students. The selected students were from the bachelor program of transportation engineering and possessed strong background of transportation planning and data collection instruments. These students were instructed for the contents and objectives of questionnaire survey. They were also trained in respect of survey methods used in this study. Self-completion and interview approaches were used considering the convenience of the respondents and ensuring the reliability of the data. One-day pilot survey was conducted with 15 respondents before an actual survey in order to check the items of questionnaire for accuracy and comprehensiveness. Categories of the personal information are male (11), female (04), single (12), married (03), under 30 years (10) and more than 30 years (05). All the respondents of pilot survey owned a car and belonged to different professions. The questionnaire was revised as per findings of the pilot survey. Actual survey was conducted at offices of some private and public organizations and in the University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore. These places were selected considering the target groups of this designed questionnaire, i.e., daily travelers, and current and potential car users. At each location, respondents were selected randomly and survey forms were completed or distributed as per convenience of the respondents. One week was given to the respondents for filling in questionnaire that was collected back with the help of students. Additional time was given to those respondents who were not able to complete in the allocated time. The only problem the students faced during survey was to convince people and ask for some time to fill in the questionnaire. Some people denied filling the form because of privacy and security reasons. Totally, 375 questionnaires were filled, but 21 of them were discarded due to incomplete and/or incorrect information. Therefore, only 354 questionnaires were used for analysis.

4 Analysis of survey data

The collected data were analyzed using factor analysis and structural equation modeling approach in hope to make significant inferences.

4.1 Distribution of respondents’ personal and trip attributes

Personal and travel information of respondents is presented in Table 1. Most of the respondents were male and single as it was difficult to get proper response from female travelers due to some cultural, religious and social constraints. Also considering religious, social and cultural constraints in Lahore, carpooling service would be more feasible for male travelers. In addition, working population of females is less in Lahore. Usually they work in office-based jobs, with a quite less share in commercial sectors such as shops and markets. Female trip rate also indicates the same trend, which is about one-third of the male trip rate in Lahore [2]. Most of the respondents are engineering students and fall in young age group. Most of them belong to middle- and high-income groups and have more potential of using car at present as well as in the future, which makes it consistent with the sampling strategy of this study. Most of the respondents travel by car, motorcycle and university bus, and some of them get pick-and-drop facility by their family members or friends or office transport. As most of the respondents are students, their main trip purpose is education. More than half of them have cars at home and drive a car.

4.2 Distribution of responses on various carpooling aspects

This section presents results of respondents’ intentions to use carpooling and its various aspects. Figure 1a shows that most of the respondents have willingness to use carpooling service if HOV lanes exist on highways. Figure 1b shows that most of the respondents have intention to share ride with three or more persons as sharing ride with more people would help in reducing their travel cost; however, it may increase travel time. Figure 1c shows that even half of travel cost reduction in current cost would have significant impact in promoting carpooling service. Figure 1d shows that this service would have more potential for students and shopping trips considering the share of young population of Lahore City.

4.3 Factor analysis on users-stated perceptions

Factor analysis is a useful technique to categorize users’ responses on observed variables into different unobserved or latent variables in order to make some significant interpretations on travel behavior parameters. In using this approach to data analysis, we examined the covariance structure among a set of observed variables in order to gather information on their underlying latent constructs (i.e., factor). It is concerned with the extent to which observed variables are generated by the underlying latent constructs, and thus, the strength of regression paths from the factors to the observed variables (the factor loadings) is of primary interest. In this study, the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) approach was considered for various situations. The EFA is designed for the situation where links between the observed and latent variables are unknown or uncertain. The analysis thus proceeds in an exploratory mode to determine how and to what extent the observed variables are linked to their underlying factors. Typically, the researchers wish to identify the minimal number of factors that account for covariation among the observed variables. To check the reliability of collected data, Cronbach’s alpha values were also determined for each extracted factor as presented in the last column of each table. The factor loadings and Cronbach’s alpha values for all parts show significant internal consistency among respondents in evaluation. The results of factor analysis for different aspects of carpooling are stated in the following subsections.

4.3.1 Social, environmental and economic aspects of carpooling

Table 2 presents the two extracted factors for traveler’s response on benefits of using carpooling as a traveling mode, including ‘social-environmental benefits’ and ‘economic benefits.’ The factor of social-environmental benefits depicts that the reduction in energy consumption, congestion, and environmental and social problems is the significant benefits of carpooling as perceived by respondents. The factor of ‘economic benefits’ shows that travelers expect a decrease in travel cost and time with the use of carpooling. These results imply that such social, environment and economic aspects of traveling need to be considered in devising appropriate carpooling policy for Lahore City. Moreover, travelers having more concern on social, economic and environmental issues would have more potential of using carpooling.

4.3.2 Motives for shifting to carpooling

The EFA resulted in three factors for traveler’s propensity for shift to carpooling considering various incentives and disincentives. The three extracted factors, as presented in Table 3, include disincentives on car use, parking incentives on carpooling and carpooling service leisure. The first factor shows that restricted parking and high travel cost of private car usage would have more impact on the shift from private vehicle to carpooling. The second factor ‘parking incentives on carpooling’ indicates that free parking and preferential treatment for carpooling vehicle at parking facilities would result in significant promotion of carpooling. People will also prefer to use it if they feel it is safe. The last factor ‘carpooling service leisure’ includes convenience, comfort and friendliness aspects of carpooling service quality. The associated factor loadings show that a convenient, comfortable and users friendly service has more potential of attracting people.

4.3.3 Reasons for preferring private vehicle over carpooling

Three appropriate factors were extracted on travelers’ reasons for preferring private vehicles to carpooling service. These extracted factors include personal constraints, service constraints and liberty constraints as presented in Table 4. The first factor ‘personal constraints’ shows that the travelers who possess strong belief on personal security, comfort and privacy would prefer to use their private vehicle over carpooling. Service constraints of carpooling may result in high preference for the use of private vehicles over carpooling. Liberty constraint factor depicts that the people who have high belief on privacy and freedom aspects in traveling would continue to use their private vehicle.

4.3.4 Lifestyles and attitudinal aspects of carpooling

The EFA resulted in two factors for traveler’s lifestyles and attitudinal aspects of traveling. Table 5 shows the details of the two extracted factors, i.e., pro-auto attitudes and pro-carpooling attitudes. These results show that people with strong pro-auto attitudes would have low propensity of using carpooling service, whereas people with strong pro-carpooling attitudes would have more potential to use carpooling as their mode of travel for commuting or education purpose. For the promotion of carpooling service, it is required to develop pro-carpooling attitudes among travelers.

4.4 Structural model of carpooling with attitudes and personal attributes

In this study, a structural model was developed of carpooling policy with extracted factors of lifestyles and attitudes of travelers (i.e., pro-car attitudes and pro-carpooling attitudes). Structural equation modeling (SEM) is a multivariate statistical analysis technique that is used by many researchers in different fields, e.g., life sciences, behavioral sciences, social science and transportation research [8, 9, 30,31,32,33].

At this stage, some observed variables were defined related to personal and travel attributes of respondents. Many variables were defined and tested; however, in the model as shown in Fig. 2 only meaningful and significant variables are reported. All these variables were coded as (1, 0). For example,

-

Marital status: 1 if marital status is single; 0 otherwise.

-

Profession: 1 if the respondent is employee; 0 otherwise.

-

Traveling mode: 1 if the travel mode is private vehicle (car, motorcycle and pick and drop on private vehicle); 0 otherwise.

-

Intentions to carpool with people: 1 if one has intention to carpool with 3 or more persons; 0 otherwise.

-

Main purpose of carpooling: 1 if the main purpose is shopping; 0 otherwise.

For the construction of structure, the carpooling policy variable (If HOV lanes exist, are you willing to choose carpooling as the mode of your trip?) is coded as 1 or 0, i.e., ‘1’ if respondents have intentions to use this service either always or occasionally and ‘0’ otherwise. The structural model in Fig. 2 shows that the relationship between pro-carpooling attitudes and defined carpooling endogenous variable is positive and significant at 1% significance level, whereas the relationship of pro-auto attitudes with carpooling variable is insignificant. The positive relationship depicts that people who possess pro-carpooling attitudes would have more propensity of using carpooling. The positive and significant relationship between marital status (single) and carpooling variable tells that the unmarried people might have more potential to use this service as travel behavior of married people becomes more family oriented and it is difficult for them to avail such a service. It is true because in many households, male members need to drop their children at school and working woman at her office. Bachelor people feel more independent and may therefore be attracted by such a service. The employees of organizations would have more potential to use this service, as structural relationship between both variables is positive. The relationships of private vehicle mode and persons to share three or more with carpooling are positive. From the results, it is evident that current private vehicle users have willingness to share vehicle with others that might be for reduction in travel cost. The positive relationship of main carpooling purpose with carpooling policy variable indicates that people may prefer to use this service for shopping purpose. It can be true considering the share of students in sample size. Most of the students prefer to share ride while going for shopping, as this helps them in reducing the travel cost and makes their journey more enjoyable with friends. The ratio of Chi-square to the degree of freedom (DF) <5 indicates a reasonable fit of model [34], goodness of fit index (GFI) >0.90 indicates a good fit of model [35, 36], and root mean square residual (RMR) <0.08 indicates the acceptability of model [37]. Considering these recommended values, it is argued that the developed structural model has certain reliability in predicting the behavior.

5 Conclusions and implications

This paper diagnoses some key determinants for consideration of carpooling policy. It is found that social, environmental and economic benefits of carpooling service would have significant impact on user’s propensity for using this mode. Other researchers have also reported similar benefits of using carpooling as perceived by travelers [3, 5]. The findings implicate that the provision of carpooling service would be able to reduce travelers’ cost with improved social and environmental conditions of the city as it will help in reducing vehicle miles travelled and energy consumption that are detrimental to the society and environment. Disincentives on car use, parking incentives on carpooling, and comfort and convenience attributes are major motives for travelers to use carpooling service. In addition to these factors, other mentioned motives in previous studies include driving alone, trip purpose, parking cost and Web-based application of service [8, 14, 20]. High travel cost and limited parking space for car usage, and preferential and free treatment with carpooling vehicles at parking facilities would help in promoting use of carpooling service. On the other hand, major constraints in promoting the use of this service include personal constraints, privacy and freedom of travelers, and limitations of carpooling service such as time-consumingness and unpunctuality. These findings are different from other studies [3, 20, 24] in terms of personal and freedom factors, as previous studies have mostly focused on the service and operational aspects of carpooling service in comparison with other modes. These findings imply that the people who have strong belief on such constraints in traveling would not prefer carpooling service to their private vehicles. Other significant factors include traveler’s pro-auto and pro-carpooling attitudes, marital status (single), current travel mode (private car), profession (employees) and trip purpose (shopping) of carpooling. It is argued that the people who possess strong pro-auto attitudes would prefer to use their private vehicles and those who hold strong pro-carpooling attitudes would have more propensity of considering carpooling service as their traveling mode in future. Travelers may prefer carpooling to private vehicle if they realize a significant reduction in travel cost, and if this service is comfortable, convenient and safer for them. Carpooling programs need to be designed considering traveler’s needs and desires. These programs should focus on minimizing the constraints in the use of carpooling and maximizing the related benefits. In this regard, supporting infrastructure and incentives on carpooling would be key instruments and may include preferential treatment to carpooling vehicles on roads and in parking areas. In addition, organizations- and educational institutions-based carpooling programs have more potential to be initiated in Lahore City, where many employment zones and institutions concentrate. Employees and students can be encouraged to participate in carpooling, as it will help them to reduce travel cost and make their trip more meaningful and enjoyable. It is also required to develop carpooling-oriented attitudes among people in order to make proper promotion. For this purpose, soft TDM policies can be adopted (e.g., education and awareness campaigns and marketing programs).

These findings are derived from a stated preference survey, and such responses always contain biases, as actual responses of travelers might be different from the stated ones. However, such biases can be reduced by carefully designing the questionnaire and conducting the survey. In this study, the questionnaire items were designed seeking the target groups of travel market. However, the size of collected samples is small and represents only some specific segments of travel market, and hence, the devised policies from the survey results may have limitations in their implications. There is a need of post-study after implementation of carpooling policy to check the actual behavior of travelers. Future studies related to carpooling service should focus on investigation of perceptions of other travelers group, e.g., employees of specific organizations. Though bias exists in the results of survey, we believe that the policy suggestions made in this study are helpful to local planners and decision makers in implementation. It will provide them with a good background of significant factors that can affect the acceptability and effectiveness of this policy in the local context.

References

Ferguson E (2000) Travel demand management and public policy. Ashgate Publishing, Vermont-USA

JICA Lahore Urban Transport Master Plan in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Final Report Volume I&II, March 2012. Retrieved from JICA online library website: http://libopac.jica.go.jp

Sheldon R, Heywood C Demand for carpooling in the UK. Accent Marketing and Research Ltd., pp 49–64

Tare SR, Khalate NB, Mahapadi AA (2013) Review paper on carpooling using android operating system: a step towards green environment. Int J Adv Res Comput Sci Softw Eng 3(4):54–57

Seyedabrishami S, Mamdoohi A, Barzegar A, Hasanpour S (2012) Impact of carpooling on fuel saving in urban transportation: case study of Tehran. Procedia Social Behav Sci 54:323–331. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.751

Chan ND, Shaheen SA (2012) Ridesharing in North America: past, present, and future. Transp Rev 32(1):93–112. doi:10.1080/01441647.2011.621557

Manzini R, Pareschi A (2012) A decision-support system for the carpooling problem. J Transp Technol 2(2):85–101. doi:10.4236/jtts.2012.22011

Javid MA, Okamura T, Nakamura F, Tanaka S, Wang R (2016) People’s behavioral intentions towards public transport in Lahore: role of situational constraints, mobility restrictions and incentives. KSCE J Civ Eng 20(1):401–410. doi:10.1007/s12205-015-1123-4

Javid MA, Okamura T, Nakamura F, Tanaka S, Wang R (2015) Factors influencing the acceptability of travel demand management (TDM) policies in Lahore: application of behavioral theories. Asian Transp Stud (ATS) 3(4):447–466. doi:10.11175/eastsats.3.447

Beirao G, Cabral JAS (2007) Understanding attitudes towards public transport and private car: a qualitative study. Transp Policy 14:478–489. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2007.04.009

Steg L (2005) Car use: lust and must. Instrumental, symbolic and affective motives for car use. Transp Res Part A 39:147–162. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2004.07.001

Bin S, Dowlatabadi H (2005) Consumer lifestyle approach to U.S. energy consumption and the related CO2 emissions. Energy Policy 33:197–208. doi:10.1016/S0301-4215(03)00210-6

Hildebrand ED (2003) Dimensions in elderly travel behavior: a simplified activity-based model using lifestyle clusters. Transportation 30(3):285–306. doi:10.1023/a:1023949330747

Correia GHA, Silva JA, Viegas JM (2013) Using latent attitudinal variables estimated through a structural equations model for understanding carpooling propensity. Transp Plan Technol 36(6):499–519. doi:10.1080/03081060.2013.83089

Prillwitz J, Barr S (2011) Moving towards sustainability? Mobility styles, attitudes and individual travel behavior. J Transp Geogr 19(6):1590–1600. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2011.06.011

Anable J (2005) ‘Complacent car addicts’ or ‘aspiring environmentalists’? Identifying travel behavior segments using attitude theory. Transp Policy 12(1):65–78. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2004.11.004

Li J, Embry P, Mattingly SP, Sadabadi KF, RasmidattaI Burris MW (2007) Who chooses to carpool and why? Examination of Texas carpoolers. Transp Res Record J Transp Res Board 2021:110–117. doi:10.3141/2021-13

Sharma NB, Kalaanidhi S, Gunasekaran K (2014) Study on willingness of commuters for carpooling on a selected corridor in Chennai. In: Proceedings of 11th conference on transportation planning and implementation methodologies in developing countries, 10–12 December, Bombay, India

Correia G, Viegas JM (2011) Carpooling and carpool clubs: clarifying concepts and assessing values enhancement possibilities through a stated preference web survey in Lisbon, Portugal. Transp Res Part A 45:81–90. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2010.11.001

Ciari F (2012) Why do people carpool: results from a Swiss survey? In: Swiss transport research conference, 2–4 May 2012

Shaheen SA, Chan ND, Gaynor T (2016) Casual carpooling in the San Francisco Bay Area: understanding user characteristics, behaviors, and motivations. Transp Policy 51:165–173. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.01.003

Arnold RE, Elston DS (2010) Casual carpooling scan report. Exploratory Advanced Research Program, Federal Highway Administration

Waerden P, Lem A, Schaefer W (2015) Investigation of factors that stimulate car drivers to change from car to carpooling in city center oriented work trips. Transp Res Procedia 10:335–344

Malodia S, Singla H (2016) A study of carpooling behavior using a stated preference web survey in selected cities of India. Transp Plan Technol 39(5):538–550. doi:10.1080/03081060.2016.1174368

Erdogan S, Cinzia C, Tremblay JM (2015) Ridesharing as a green commute alternative: a campus case study. Inte J Sustain Transp 9(5):377–388. doi:10.1080/15568318.2013.800619

Srivastava B (2012) Making carpooling work: myths and where to start. Smarter transportation. IBM research report

Soltys KA (2009) Toward an understanding of carpool formation and use. Department of Geography and Planning, University of Toronto

Watts R, Belz N, Fraker J, Gandrud L, Kenyon J, Meece M (2010) Increasing carpooling in Vermont: opportunities and obstacles. UVM Transportation Research Center, University of Vermont

Delhomme P, Gheorghiu A (2016) Comparing French carpoolers and non-carpoolers: which factors contribute the most to carpooling? Transp Res Part D Transp Environ 42:1–15. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2015.10.014

Jang TY, Hwang JW (2009) Direct and indirect effects on weekend travel behaviors. KSCE J Civ Eng 13(3):169–178. doi:10.1007/s12205-009-0169-6

Eriksson L, Nordlund AM, Garvill J (2010) Expected car use reduction in response to structural travel demand management measures. Transp Res Part F 13:329–342. doi:10.1016/j.trf.2010.06.001

Steg L (2003) Factors influencing the acceptability and effectiveness of transport pricing. In: Schade J, Schlag JB (eds) Acceptability of transport pricing strategies. Pergamon Press, Oxford, pp 187–202

Golob T (2003) Structural equation modeling for travel behavior research. Transp Res Part B 37:1–25. doi:10.1016/SOl9l-2615(01)00046-7

Marsh HW, Hocevar D (1985) Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: first and higher-order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychol Bull 97:562–582. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.97.3.562

Bentler PM, Bonett DG (1980) Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of co-variance structures. Psychol Bull 88:588–606. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

Bentler PM (1988) Causal modeling via structural equation systems. In: Nesslroade JR, Cattell RB (eds) Handbook of multivariate experimental psychology, vol 2. Plenum, New York, pp 317–335

Hu LT, Bentler PM (2009) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structural analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternative. Struct Equ Model 6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted at University of Engineering and Technology Lahore with support of Department of Transportation Engineering and Management Department. Authors are thankful to all the people who helped in this research work especially in conducting the questionnaire survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Part 1: Personal and traveling information of respondents |

Gender, age, marital status, vehicle ownership, monthly income, education, profession, daily traveling mode, driving license, do you drive a car, etc. |

Part 2: Characteristics of the travelers to the stated carpooling scenarios |

(a) If HOV lanes exist, are you willing to choose carpooling as the mode of your daily trip? |

(1) Yes, I would always choose carpool, (2) yes, I would occasionally choose carpool, (3) never |

(b) If yes in above question, then how many people do you like in carpooling with you? |

(1) One person, (2) two persons, (3) three persons, (4) more than three persons |

(c) How much travel cost reduction would encourage you to choose carpooling as the mode of your trip? |

(1) Less than 20%, (2) 50%, (3) 75%, (4) 100% |

(d) Which of the following would best describe your carpooling purpose? |

(1) Travel to university/school, (2) travel to office, (3) travel to shopping, (4) other |

Part 3: If you have intention to use carpooling, what do you think are the most important benefits of carpooling? |

(a) To save money on fuel |

(b) To save money on parking |

(c) To reduce impact on environment |

(d) If I can find people who travel at similar days and time to mine, I definitely be interested in carpooling |

(e) To meet with people (friends, colleagues) |

(f) To reduce traffic congestion |

(g) To reduce energy consumption |

(h) To save time |

(i) For less stress |

Part 4: Motives for shift to carpooling and reasons of preferring private vehicle |

I will shift to carpooling service if |

(a) It is expensive to travel on private car |

(b) I feel safe |

(c) Journey is enjoyable with friends |

(d) Shortage of parking for car at destination |

(e) Parking fee is imposed on car use |

(f) Carpooling service is provide on my area |

(g) Carpooling service is more comfortable |

(h) Preference is given to HOVs in parking lots |

(i) I get free parking |

I prefer car/motorcycle over carpooling because |

(a) Not knowing who my fellow passenger might be like |

(b) Of time saving |

(c) Of fellow passenger would not be ready to arrive or leave when I am ready to |

(d) No legal implications if there is an accident |

(e) Not comfortable with giving out my phone number to unknown person |

(f) Of security issues |

(g) Of comfortably |

(h) Of privacy |

(i) It will restrict my freedom |

Part 5: Statements on lifestyles and attitudes |

(a) It is cool to travel on a car |

(b) I try to avoid being near to unfamiliar people |

(c) I like something new and different |

(d) I care more about myself than the others |

(e) I cannot trust strangers |

(f) Shorter travel time is the priority for transportation |

(g) Reliability is the priority for transportation |

(h) Safety is the priority for transportation |

(i) I hate an uncomfortable ride |

(j) Flexibility of route choice is the priority for transportation |

(k) Cheaper fare is the first priority |

(l) Traveling mode reflects my personality image |

(m) I like ride sharing with my friends or colleagues going to work/study |

(n) I prefer ride sharing with my family members going to work/study |

(o) I prefer to live near to my work/study place |

(p) Shortest route is the priority in traveling by car |

(q) I hate long driving because it causes stress to me |

(r) I do consider the impact on environment while I use a car |

(s) I believe that car use is a cause of traffic congestion |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Javid, M.A., Mehmood, T., Asif, H.M. et al. Travelers’ attitudes toward carpooling in Lahore: motives and constraints. J. Mod. Transport. 25, 268–278 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40534-017-0135-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40534-017-0135-9