Abstract

We present an executive summary of a guideline for management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care written by the European Geriatric Medicine Society, the European Diabetes Working Party for Older People with contributions from primary care practitioners and participation of a patient’s advocate. This consensus document relies where possible on evidence-based recommendations and expert opinions in the fields where evidences are lacking. The full text includes 4 parts: a general strategy based on comprehensive assessment to enhance quality and individualised care plan, treatments decision guidance, management of complications, and care in case of special conditions. Screening for frailty and cognitive impairment is recommended as well as a comprehensive assessment all health conditions are concerned, including end of life situations. The full text is available online at the following address: essential_steps_inprimary_care_in_older_people_with_diabetes_-_EuGMS-EDWPOP___3_.pdf.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

What is new?

-

The purpose of the guideline is to be inclusive.

-

Both for patients and for the primary care multi-disciplinary team.

-

Recommendations focus on safety and early detection of risk for dependence.

-

Along with recommendations for escalation of treatment according to patients’ characteristics, criteria for de-escalation are presented.

-

When appropriate, frailty and cognitive impairment screening-based interventions are presented.

-

Preventative strategies include nutrition and oral health care, exercise, and immunisations.

-

Classical complications of diabetes are presented along with new complications including falls, frailty, depression and cognitive disorders.

Introduction and purpose of the guidelines

This guideline aims to improve standards of diabetes care of older community-based adults with diabetes managed by their primary care team. We expect that each participant of the multi-disciplinary team in primary care including medical practitioners, dieticians, pharmacists, therapists, residential care staff, nurses and specialist diabetes nurses, and finally social workers will find effective support with this guideline. The healthcare stakeholders should also find elements for pathways of care construction adapted to their local and/or regional organization and policies.

This Guideline has three main purposes:

-

(1)

Identify a series of recommendations and Best Clinical Practice Statements in key areas that will support health and social care professionals in everyday local primary care settings to manage more effectively the complex issues seen in older adults with diabetes

-

(2)

Arrive at a consensus among European specialists in diabetes and geriatric medicine on how we approach the management of important issues in managing older people with diabetes

-

(3)

Provide a platform for commissioners of healthcare and policy makers in each nation across the European continent to plan a model care pathway that enhances diabetes care in older people in terms of quality and clinical outcomes.

1A Rationale for high quality diabetes care in older people

Across Europe, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a highly prevalent chronic disease, particularly in people older than 65 years. Since 2000 approximatively 50% of people receiving treatment for diabetes in Europe are older than 65 y or 70 y and 25% older than 75 y. The growth of the total adult population with diabetes can average 6% per year [1]. Between 10 [2] and 26% [3] of older people suffer from diabetes with a variable proportion of undiagnosed diabetes.

Diabetes is a long-standing chronic disease with a high personal and public health burden. People with diabetes are at high risk for disability, poor quality of life and increased mortality. This higher risk is observed well into old age.

Finally, the care of people with diabetes represents a very important portion of direct and indirect care costs in Europe. Direct costs accounted for 2.5–6.6% of direct costs and these costs are higher in those with complications or with insulin and particularly due to hospitalisations [4].

1B Defining the special needs of the older adults

Older people with T2DM will benefit from locally relevant interdisciplinary diabetes care teams in the community as part of a specific primary care initiative. Focusing on patient’s safety, recognising early health deterioration and maintaining independence as longer as possible should minimize avoidable hospital and emergency department admissions and institutionalization. Special attention to quality of life until a dignified death is also necessary for these patients.

Because of the frequent lack of evidence in the treatment of the oldest category of patients, there is also a need to promote high quality clinical research and auditing in the area of diabetes management in the community and primary care setting.

1C Who should read this guideline?

Every member of the community-based and primary care teams who has direct care responsibility for older people with diabetes in their local area throughout the European community. This will also include dieticians, pharmacists, therapists, residential (non-nursing and nursing) care staff, community-based and primary care nurses as well as specialist diabetes nurses where available. This should also include those in health and social care who also provide care for this often vulnerable sector of the diabetes population.

The healthcare stakeholders should also find elements for pathways of care construction adapted to the regional organization and policies.

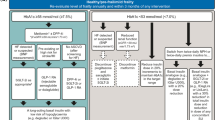

1D Key principles underpinning this guideline (Fig. 1)

= Guidance

Detailed recommendations are available in the EUGMS website (see the online version with the link Essential_steps_inprimary_care_in_older_people_with_diabetes_-_EuGMS-EDWPOP___3_.pdf. This executive summary presents a selection of the most important recommendations (Table 1).

= Preventative actions

A part of the guidance is devoted to prevention with education for health with empowerment of the older subjects and care givers. The strategy includes monitoring of the risk factors markers (blood glucose, blood pressure, lipids and electrocardiogram), heathy and sustainable diet-based avoiding restricted diets and incentive for physical activity, with both endurance and resistance training particularly in frail subjects. Oral health care and immunisations completes the preventative actions.

= Individualised care plan

Owing to the high level of heterogeneity of older people with T2DM health care plan relies on careful assessment of needs. We proposed the use of gerontological and metabolic assessments to define an integrative and individualised care plan constructed and updated with the subject and the multidisciplinary care team. Figure 1 provides an overview of the guiding principles of the guidelines and how they are connected.

Graduation of risk derives from this comprehensive assessment and should support all action decisions.

Update of the care plan is an important issue because T2DM is a long-standing chronic disease and health status and care needs of the subject may varying according to time diabetes care, to intervention on risk factors and frailty or after an acute event. Frailty screening is a major step in the construction of the care plan because frailty may be reversible with targeted interventions on blood glucose and blood pressure control, and nutrition and physical activity. This procedure is in line with the program of the world health organization and named ICOPE (integrated care for older people, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-FWC-ALC-19.1).

= Digital health

Digital health tools are underused in older people probably due to preconceived ideas and digital divide. We suggest that a diabetes management app for older people should include the following elements of care and intervention: glucose levels, nutritional plan, exercise plan, blood pressure record, hypoglycaemia alert messages, help with insulin dosages, contact telephone and SMS text messaging to GP practice and community nurses, and sick day rules.

Format and methodology of the Guideline

2A Format and structure

The working group included members of the EuGMS SIG diabetes (European geriatric Medicine Society Special Interest Group diabetes), the EDWPOP (European Diabetes Working Party for Older people), invited general practitioners and Philip Ivory, a patients’ advocate.

The format of the guidance follows the template of the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Global Guideline on the Management of Type 2 Diabetes (2013) [5]. The full guidance includes 4 parts after definition of aims, scope and methodology of the guidelines. In each section and subsection of the full text rationale and evidences supporting the recommendations are presented as well as corresponding key references. Part one details the recommendations that enhance the practice and quality of primary care management of diabetes. The overall preventative strategy, monitoring, comprehensive patient assessment, and follow-up principles are documented. Recommendations for drug treatments are exposed in part 2. The management of complications in the broad sense and the care of specific situations that patients may encounter are detailed in parts 3 and 4, respectively. Finally, the different scales of frailty screening are presented in the online link via the EuGMS website.

2B Search methodology

The primary strategy attempted to locate any relevant systematic reviews or meta-analyses, or randomised controlled and controlled trials. However, as discussed above, there were inherent limitations to this approach due to the lack of available clinical trial or observation data in this field.

The following databases were examined: Embase, Medline/PubMed, Cochrane Trials Register, CINAHL, and Science Citation. Hand searching of at least 12 major diabetes and ageing/geriatric medicine journals was also undertaken by the Writing Group. The searches were limited to English language citations over the previous 15 years. The research was last updated in December 2022.

2C Grading recommendations

Considering the available evidence and the consensus of the experts, recommendations are graded according four categories as follows:

-

4A—Higher strength—evidence from meta-analyses/systematic reviews of RCTs, RCTs with low risk of bias

-

3A—Moderate strength—evidence from RCTs with a higher risk of bias, systematic reviews of well-conducted cohort or case control studies

-

2A—Lower strength—evidence from well-conducted cohort or case–control studies

-

1A—Expert Opinion (no direct evidence available)—to be used as ‘Good Clinical Practice’

Glucose-lowering treatment recommendations

Type 2 diabetes mellitus requires a holistic control of different metabolic disorders, including control of blood pressure, plasma lipids, heart rhythm, and blood glucose. This executive summary focuses specifically on the glucose control by glucose-lowering treatment.

Some specific management procedures need be considered for older people compared with adults. First, the potential risks and benefits of glucose-lowering treatment should be carefully balanced to determine the appropriate choice of glycaemic targets. Second, a special attention should be placed to strictly avoid hypoglycaemia. As a result, the choice of certain hypoglycaemic agents (such as sulphonylureas, for example) will be prioritised differently than for younger patients. Then, the choice of treatment will be individualised according to the patient's characteristics. A detailed assessment of the patient as a whole (including an assessment of frailty, or other geriatric characteristics) is, therefore, absolutely essential.

Of the recent guidelines for the management of type 2 diabetes, only a few make specific recommendations for older people have been produced and the possible shortcomings of these have been reviewed recently [6]. The new EuGMS–EDWPOP guideline, whose recommendations are presented in this Executive Summary, are entirely addressed to the care and needs of older patients with diabetes. 3A glucose-lowering treatment.

Pharmacological glucose regulation is based on the use of glucose-lowering agents which provide cardiovascular (CV) safety and protection. Older people with diabetes often have multiple risk factors for hypoglycaemia developing during treatment and these include chronic renal disease, erratic eating meal patterns, dementia, polypharmacy, and even frailty that should be considered. Some glucose-lowering agents have a high risk of hypoglycaemia (sulfonylureas, glinides and insulin), while others have a low (and even null) risk of hypoglycaemia (metformin, DPPIV inhibitors, SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists). In older people with type 2 diabetes, hypoglycaemia should be avoided.

Metabolic targets

For fit independent patients, a tight HbA1c is acceptable, while in less fit individuals with multiple comorbidities and organ dysfunctions, more relaxed targets are more reasonable to avoid the side effects of medications and the risk of hypoglycaemia. [7] A target blood pressure (BP) of < 130/80 mmHg, if tolerated, is reasonable in fit independent older people with diabetes as it is associated with a reduction of cardiovascular risks, while in less fit individuals, higher targets are reasonable as low BP may be associated with adverse events including mortality. [8] Although most of lipid trials were conducted in younger population, it appears that the magnitude of risk reduction in older people is similar to younger patients. The evidence for statin therapy is established for older people with diabetes up to the age of 80 years. However, reduction of intensity of statin therapy may be required in less fit individuals. In addition, the effects of high or moderate intensity statin use in care home residents may not have positive effects on avoiding hospital admissions or reduction of mortality. [9] Therefore, in this group of fully dependent population a clinician discretion is required about reduction of intensity or complete withdrawal of treatment with aim focused on quality of life and reducing polypharmacy. (Table 2).

These glucose-lowering agents can be used in older people following a suggested strategy (Fig. 2), based on the potential benefits and harm of each therapeutic classes, and on the key issues and concerns that should be considered in the clinical decision.

Regarding non-insulin agents, metformin at the lowest dose possible is a suitable first line therapy due to its low risk of hypoglycaemia and CV benefits. Metformin should be avoided in people with significant cardiovascular disease, chronic renal disease, weight loss and acute illness. Dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP4i) are an alternative to metformin when contra-indicated or not tolerated, or a second-line treatment with metformin in frail or dependent subjects (if HbA1c still > 58 mmol/mol). DPP4i have gastro-intestinal side effects, and a dose adjustment is needed in chronic kidney disease. Both sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) are suitable choices for second-line treatment with metformin to limit the worsening of cardiovascular disorders or renal failure, particularly in obese patients (GLP-1Ra apart of their glucose-lowering properties. However, their use should be balanced in subjects at risk for side-effects. SGLT2i are not suitable for moderately–severe frailty, or for care home residents with weight loss. They increase the risk of urinary tract infections, candidiasis, dehydration, hypotension, and diabetic ketoacidosis. The effect on glucose regulation is poor if eGFR is lower than 60 ml/min. GLP-1Ra’s not suitable for subjects with chronic renal impairment or care home residents with weight loss or renal impairment.

Sulfonylureas (SU) are low-cost drugs and have an effective glucose-lowering effect. They are possible second-line option if economic considerations are central to the decision. However, they have a high risk of hypoglycaemia, a high rate of interactions with other drugs, and potential cardiovascular side-effects with an excess of mortality. They should be avoided in severe renal impairment. Glinides (e.g., Repaglinide) is similar to SU in terms of glucose-lowering effect efficiency, but they have a medium risk of hypoglycaemia. They have an extended half-life in older people, and in cases of renal impairment, and there is only a little data for their use in older people. Both SU and glinides should be used with the highest caution in older people.

The use of insulin in addition to metformin is a third-step strategy. Different options may be considered. The use of once daily long-acting basal insulin offers easy titration, flexible administration, less weight gain and low risk of hypoglycaemia. However, it is less physiologic with postprandial glucose excursions. The use of twice daily combination (or premixed insulins) is simple, with fixed doses, and provides a good glycaemic control. However, it is subject to weight gain, hypoglycaemic risk and it is only suitable for patients with regular eating patterns. The use of basal–bolus insulin is the most physiological in its effects on glucose-levels, and provides a good glycaemic control. However, it requires a complex titration, frequent injections, staff training in care homes, and has a high risk of weight gain and hypoglycaemia. Finally, insulin can be combined with GLP-1RAs, offering a lower risk of hypoglycaemia and delaying the use of complex insulin regimens. The restrictions and disadvantages are the same as GLP-1Ra’s alone (see above).

DPP4i: dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors; SU: sulfonylureas; SGLT2i: sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors; GLP-1Ra: glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists; BMI: Body Mass Index; * Sulfonylureas with low-risk of hypoglycaemia; insulin: basal, basal–bolus or premix.

3B De-escalation of glucose-lowering treatment

De-escalation of treatments should be considered for several conditions, as outlined in Box 1, to avoid overtreatment in older adults. This is the case either when the risk of hypoglycaemia is too great, or when the expected benefit of the treatment is not certain.

Hypoglycemic medications were safely withdrawn in a cohort of frail nursing home older adults with type 2 diabetes, mean age 84.4 ± 6.8 years, [13] and in another group in the community, mean age, 86.5 ± 3.2 years, who were attending outpatient clinics without deterioration of their glycemic control [14]. Their main features were significant weight loss, increased comorbidities, including dementia, and polypharmacy, with recurrent hypoglycemia. Therefore, people with these criteria appear to be suitable candidates for a trial of deintensification or withdrawal of hypoglycemic medications.

Screening for Frailty and Cognitive Impairment

Frailty screening is a crucial part of the assessment of older patients with T2DM. However, implementation in routine primary care can be difficult due to limited time. Besides the historical criteria [15] and scales [16, 17], operational tools have been developed adapted to clinical practice. Clinical features pointing to frailty include general symptoms such as exhaustion, examination data such as muscle weakness, weight loss, slow walking speed, and cognitive impairment, behaviour changes such as low physical activity and finally comorbidity, sensorial impairments and polypharmacy. Some tools need to be confirmed by a more in-depth evaluation, such as the Toulouse gerontopole scale [18]or the electronic frailty index developed in the UK and based on the cumulative deficit model to identify and score frailty based on routine interactions of patients with their general practitioner [19]. The Share frailty [20] Instrument [21]is proposed for primary care setting and accessible via web calculators (https://sites.google.com/a/tcd.ie/share-frailty-instrument-calculators/translated-calculators).

Cognitive impairment is a highly prevalent condition in older people with T2DM and has a potentially important impact on treatment management (e.g., choice of treatments). The screening of cognitive impairment is, therefore, suggested at regular intervals for patients aged 70 years and over. Different tools are available to screen for cognitive impairments, such as the MoCA, MiniCog, or the Mini Mental State Examination Score [22]. The common reversible causes of cognitive impairment (e.g., delirium, medication side-effects, metabolic or endocrine disturbances, sleep problems, and depressive disorder) should be sought, through a full medical assessment.

Among the other frequent conditions in older people with T2DM, fragility fractures deserve a particular consideration. The usual markers (such as bone mineral density) are difficult to interpret in those people. It is, therefore, important to identify other risk factors, such as previous history of fracture(s) or fall(s), low grip strength, or poor glycaemic control, which should trigger the initiation of a prevention strategy [23].

Conclusions

The guideline aims to be inclusive, both for patients and the primary care multidisciplinary team. Rather than focusing on numerical targets for glycaemic control, this guide proposes an integrative approach with regular updates of the care plan. Frailty screening offers the opportunity to propose targeted preventative strategies. The development of new treatment for diabetes and new technologies should be tested in term of actions on frailty. The writing group underlines the lack of evidence in several domains and particularly in the oldest patients. However, care is facilitated with digital health instrument and older patients should benefit from this new tool. High quality research is needed in the oldest old.

References

Bourdel MI (2009) Models of care, the European perspective. In: Sinclair AJ (ed) Diabetes Old age. Wiley-Blackwell, Chippenham, pp 453–459

Bourdel-Marchasson I, Helmer C, Barberger-Gateau P et al (2007) Characteristics of undiagnosed diabetes in community-dwelling French elderly: the 3C study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 76:257–264

Makrilakis K, Kalpourtzi N, Ioannidis I et al (2021) Prevalence of diabetes and pre-diabetes in Greece. Results of the First National Survey of Morbidity and Risk Factors (EMENO) study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 172:108646

Jönsson B (2002) Revealing the cost of Type II diabetes in Europe. Diabetologia 45:S5–S12

Dunning T, Sinclair A, Colagiuri S (2014) New IDF Guideline for managing type 2 diabetes in older people. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 103:538–540

Christiaens A, Henrard S, Zerah L et al (2021) Individualisation of glycaemic management in older people with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines recommendations. Age Ageing 50:1935–1942

Lipska KJ, Krumholz H, Soones T et al (2016) Polypharmacy in the aging patient a review of glycemic control in older adults with type 2 diabetes. JAMA 315:1034–1045

Odden MC, Peralta CA, Haan MN et al (2012) Rethinking the association of high blood pressure with mortality in elderly adults: the impact of frailty. Arch Intern Med 172:1162–1168

Campitelli MA, Maxwell CJ, Maclagan LC et al (2019) One-year survival and admission to hospital for cardiovascular events among older residents of long-term care facilities who were prescribed intensive- and moderate-dose statins. CMAJ 191:E32–E39

Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A et al (2020) 2019 Update to: Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2018. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 43:487–493

Abdelhafiz AH, Sinclair AJ (2020) Cardio-renal protection in older people with diabetes with frailty and medical comorbidities - A focus on the new hypoglycaemic therapy. J Diabetes Complicat 34:107639

Abdelhafiz AH, Sinclair AJ (2018) Deintensification of hypoglycaemic medications-use of a systematic review approach to highlight safety concerns in older people with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 32:444–450

Sjoblom P, Anders Tengblad, Lofgren UB, et al. (2008) Can diabetes medication be reduced in elderly patients? An observational study of diabetes drug withdrawal in nursing home patients with tight glycaemic control. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 82(2): 197–202

Abdelhafiz AH, Chakravorty P, Gupta S et al (2014) Can hypoglycaemic medications be withdrawn in older people with type 2 diabetes? Int J Clin Pract 68:790–792

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J et al (2001) Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol 56:M146–M156

Morley JE (2009) Developing novel therapeutic approaches to frailty. Curr Pharm Des 15:3384–3395

Pulok MH, Theou O, Valk AM et al (2020) The role of illness acuity on the association between frailty and mortality in emergency department patients referred to internal medicine. Age Ageing 49:1071–1079

Hoogendijk EO, van Kan GA, Guyonnet S et al (2015) Components of the frailty phenotype in relation to the frailty index: results from the toulouse frailty platform. J Am Med Dir Assoc 16:855–859

Vellas B, Balardy L, Gillette-Guyonnet S et al (2013) Looking for frailty in community-dwelling older persons: the Gérontopôle Frailty Screening Tool (GFST). J Nutr Health Aging 17:629–631

Clegg A, Bates C, Young J et al (2016) Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing 45:353–360

Romero-Ortuno R, Walsh CD, Lawlor BA et al (2010) A frailty instrument for primary care: findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). BMC Geriatr 10:57

Stewart C, Stewart J, Stubbs S et al (2022) Mini-Cog, IQCODE, MoCA, and MMSE for the Prediction of Dementia in Primary Care. Am Fam Physician 105:590–591

Dufour AB, Kiel DP, Williams SA et al (2021) Risk factors for incident fracture in older adults with type 2 diabetes: the framingham heart study. Diabetes Care 44:1547–1555

Pilotto A, Ferrucci L, Franceschi M et al (2008) Development and validation of a multidimensional prognostic index for one-year mortality from comprehensive geriatric assessment in hospitalized older patients. Rejuvenat Res 11:151–161

Acknowledgements

The important contribution of Philip Ivory (now deceased) is warmly recognised. No other acknowledgements are declared.

Funding

No funding received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IBM, SM and AJS were the development leads of this guideline and were main the editors. All other authors contributed equally to chapter writing, commenting on drafts, and approving the final submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have declared a Conflict of Interest in this manuscript.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Statement of human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Consent to publication

All authors gave their consent to publication—no third-party approval was needed.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bourdel-Marchasson, I., Maggi, S., Abdelhafiz, A. et al. Essential steps in primary care management of older people with Type 2 diabetes: an executive summary on behalf of the European geriatric medicine society (EuGMS) and the European diabetes working party for older people (EDWPOP) collaboration. Aging Clin Exp Res 35, 2279–2291 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-023-02519-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-023-02519-3