Abstract

This paper considers a model of strategic information transmission with an imperfectly informed receiver and provides a simple logic by which the receiver’s prior knowledge becomes an impediment to efficient communication. We show that the extent of communication is severely limited as the receiver becomes more informed. Moreover, in a simple example with two signals, we show that no information can be conveyed via cheap talk for an arbitrarily small degree of preference incongruence. This result draws sharp contrast to the case with an uninformed receiver which always yields a fully separating equilibrium as long as the preferences are sufficiently congruent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Also see Austen-Smith (1993), Gilligan and Krehbiel (1989), Krishna and Morgan (2001), Battaglini (2002), and Li (2010) for works with multiple senders. Kawamura (2011) considers a setting in which senders have an incentive to “exaggerate” their preferences and show that the use of binary messages is a robust mode of communication. Kawamura (2013) also uses a similar setting to analyze how the sample size affects the quality of communication.

In contrast, Ishida and Shimizu (2014) consider a setting in which the receiver observes a signal which carries no information with some positive probability. It is shown that there is a case where the receiver’s prior knowledge enhances the amount of information conveyed via cheap talk.

In a variant of our model where the action space is continuous while the signal space is discrete, we can show that truthful communication is always possible if the preference bias is sufficiently small.

An essential feature of our model is that the action space is discrete. For practical purposes, there are several interpretations of this structure. One is that the underlying situation is such that optimal actions diverge to extreme points (the case of corner solutions), i.e., when an action is to be taken, it is always optimal to go all the way to the end point. Another possible interpretation is that there are some technical restrictions on the set of feasible actions, so that the decision maker can only take some pre-specified points in the action space.

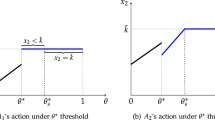

Note that in the current setup, a player’s preferred action is state independent. While this may appear to be a departure from the standard setup, this is rather a direct consequence of the fact that the action space is discrete. To be more precise, what ultimately matters in a discrete setup like this is the threshold belief at which a player is indifferent between the two actions. Since all of our subsequent results are characterized by the relationship between the threshold beliefs and the signal structures, two models are strategically equivalent if they lead to the same threshold beliefs, given a pair of preference bias parameters. Given this, we can always construct a strategically equivalent model even if the state space is continuous and a player’s preferred action is state dependent, as are common to most models in the literature.

It is easily verified that a signal structure is uninformative if and only if \( \ell _n(1) = \dots = \ell _n(K_n) = 1\).

If there are any two signals with the same likelihood ratio, we can in principle merge them into one signal.

That is, if the receiver’s private information is highly accurate by itself, her choice of action depends only on her own information, irrespective of the sender’s message, and communication plays no role.

The latter requirement is necessary to exclude truth-telling equilibria in which the receiver’s action is independent of the sender’s message, and communication hence plays no role.

The details of the derivation of the equilibrium conditions are relegated to Appendix A.

It should be noted that the theorem itself does not constitute a direct proof that better information leads to worse information transmission, because it is a non-generic result for this purpose. However, the argument can easily be extended to show that it is not a non-generic phenomenon in our environment (see Theorem 2 in Appendix B).

To verify this, note that when \(r_1=0.5\), the receiver’s best response must be \(A(h,j)=1\) and A(l, j) for \(j=h,l\). Given this, one can readily verify that there is no incentive for the sender to make a false recommendation if \(r_0>1-\beta \).

One can also show that there is no partially informative equilibrium in which the sender adopts a mixed strategy, meaning that no information can be conveyed via cheap-talk communication under this condition. Thus, for our purpose it is indeed without loss of generality to exclude mixed strategies in the first place.

To be more precise, one can show that there exists no fully informative equilibrium for any \( b > 0 \) if \( r _1 \ge r _0 \).

References

Austen-Smith, D.: Interested experts and policy advice: multiple referrals under open rule. Games Econ. Behav. 5(1), 3–43 (1993)

Battaglini, M.: Multiple referrals and multidimensional cheap talk. Econometrica 70(4), 1379–1401 (2002)

Chen, Y.: Communication with Two-sided Asymmetric Information. Mimeo (2009)

Chen, Y.: Value of public information in sender-receiver games. Econ. Lett. 114(3), 343–345 (2012)

Crawford, V.P., Sobel, J.: Strategic information transmission. Econometrica 50(6), 1431–1451 (1982)

Galeotti, A., Ghiglino, C., Squintani, F.: Strategic information transmission in networks. J. Econ. Theory 148(5), 1751–1769 (2013)

Gilligan, T., Krehbiel, K.: Asymmetric information and legislative rules with a heterogeneous committee. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 33(2), 459–490 (1989)

Ishida, J., Shimizu, T.: Can More Information Facilitate Communication? Mimeo (2014)

Kawamura, K.: A model of public consultation: why is binary communication so common? Econ. J. 121(553), 819–842 (2011)

Kawamura, K.: Eliciting information from a large population. J. Public Econ. 103, 44–54 (2013)

Krishna, V., Morgan, J.: A model of expertise. Q. J. Econ. 116(2), 747–775 (2001)

Lai, E.K.: Expert advice for amateurs. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 103, 1–16 (2014)

Li, M.: Advice from multiple experts: a comparison of simultaneous, sequential, and hierarchical communication. B.E. J. Theor. Econ. Top. 10(1) (2010)

Moreno de Barreda, I.: Cheap Talk with Two-Sided Private Information. Mimeo (2010)

Morgan, J., Stocken, P.C.: Informal aggregation in polls. Am. Econ. Rev. 98(3), 864–896 (2008)

Seidmann, D.J.: Effective cheap talk with conflicting interests. J. Econ. Theory 50(2), 445–458 (1990)

Watson, J.: Information transmission when the informed party is confused. Games Econ. Behav. 12(1), 143–161 (1996)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This research is financially supported by JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (Nos. 26380252 and 15K03352), Kansai University’s Overseas Research Program for the year of 2009 and the Global COE (GCOE) program of Osaka University. We would like to thank the editor and two anonymous referees for their useful comments on an earlier version of this article. Of course, any remaining errors are our own.

Appendices

Appendix A: Proof of Proposition 1

1.1 The equilibrium conditions for the receiver’s strategy

Given the sender’s truth-telling strategy, we have

This implies that the receiver’s best response is given by (3).

1.2 The equilibrium conditions for the sender’s strategy

We first show that \( \mathcal{S} _1 ( i , i ' ) \not = \emptyset \Rightarrow \mathcal{S} _1 ( i ' , i ) = \emptyset \) necessarily holds as long as the receiver’s strategy A satisfies (3). Suppose on the contrary that there exists \( ( i , i ' , j , j ' ) \) such that \( A ( i , j ) = 1 \), \( A ( i ' , j ) = 0 \), \( A ( i , j ' ) = 0 \), and \( A ( i ' , j ' ) = 1 \). If \( i < i ' \), then

This is a contradiction. Similarly, if \( i > i ' \), then

This is also a contradiction, therefore, it is verified \( \mathcal{S} _1 ( i , i ' ) \not = \emptyset \Rightarrow \mathcal{S} _1 ( i ' , i ) = \emptyset \). It then follows that for any \( i , i ' \in S _0 \), one of the following holds in truth-telling equilibrium:

-

(i)

\( \mathcal{S } _1 ( i , i ' ) = \mathcal{S} _1 ( i ' , i ) = \emptyset \).

-

(ii)

\( \mathcal{S } _1 ( i , i ' ) \not = \emptyset \) and \( \mathcal{S } _1 ( i ' , i ) = \emptyset \).

-

(iii)

\( \mathcal{S } _1 ( i , i ' ) = \emptyset \) and \(\mathcal{S } _1 ( i ' , i ) \not = \emptyset \).

Furthermore, it is clear that \( \mathcal{S} _1 ( i , i ' ) = \mathcal{S} _1 ( i ' , i ) = \emptyset \) implies \( {\mathbb {E}} [ u _0 ( t , A ( i , j ) ) \vert s _0= i ] = {\mathbb {E}} \left[ u _0 ( t , A ( i ' , j ) ) \vert s _0 = i \right] \). Now suppose \( \mathcal{S} _1 ( i , i ' ) \not = \emptyset \) and \( \mathcal{S} _1 ( i ' , i ) = \emptyset \). Then we have

Similarly, suppose \( \mathcal{S} _1 ( i , i ' ) = \emptyset \) and \( \mathcal{S} _1 ( i ' , i ) \not = \emptyset \). Then we have

The last inequality follows from the fact that \( j \in \mathcal{S} _1 ( i ' , i ) \) implies \( P _{ i j } \le \beta _1 < 1 - \beta _ 0 \).

Appendix B

Theorem 2

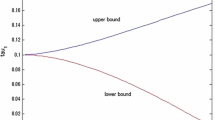

Fix \(L_0\in \mathcal F\) and \( \tilde{L}_1\in \mathcal{W}(L_0){\setminus }\{U\}\). Then, there exist non-degenerate intervals of \( b _0 \) and \( b _1 \) such that

-

there exists a fully informative equilibrium under \(L_1=U\), while

-

there exists no fully informative equilibrium under \(L_1=\tilde{L}_1\).

Proof

Similarly in the proof of Theorem 1, we can show that if

then there exists a fully informative equilibrium under \(L_1=U\).

Also similarly in the proof of Theorem 1, we can show that if

or equivalently

hold, then there exist no fully informative equilibrium under \(L_1=\tilde{L}_1\).

Combining these results, it is verified that

or equivalently

are the intervals stated in the theorem. It can also be shown that these intervals are non-degenerate. \(\square \)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ishida, J., Shimizu, T. Cheap talk with an informed receiver. Econ Theory Bull 4, 61–72 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40505-015-0076-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40505-015-0076-6